By Paul Russinoff

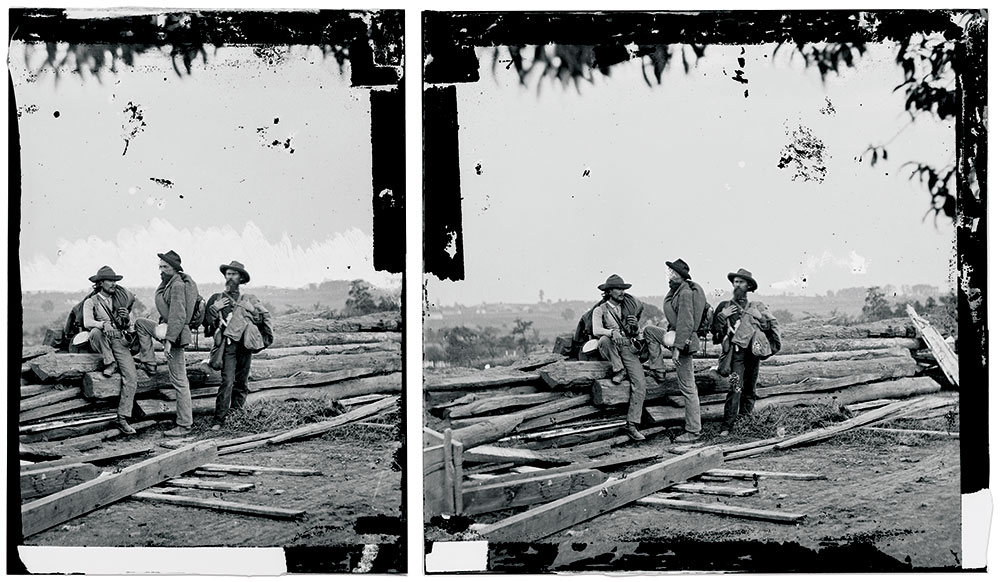

The three Confederate prisoners immortalized by Mathew Brady’s team at Gettysburg in July 1863 stands among the most compelling, evocative images of the Civil War.

Exactly who they are remains an unsolved mystery. Are they forever unknown?

My investigation into this image has its origins in June 2017. I was part of a walking tour led by the former Director of the Gettysburg Lutheran Theological Seminary Museum. As we passed the spot where the photograph was taken, my tour guide mentioned a theory: The Confederate prisoners were nurses at the Seminary, which had been pressed into service as a hospital. Moreover, and most intriguingly, a roster of Confederate nurses attached to the hospital exists.

The Director added that perhaps through researching these individuals, family photographs might emerge, and if the stars aligned a reasonably positive identification might be made. I discussed this fascinating bit of information with a few other collectors and then filed it away.

In 2021, I acquired a single albumen print (not a stereo card) of the three prisoners. Made from the original, un-cropped negative, it revealed details at the edges of the plate. Thus began an on-and-off research project that results in this story.

While I have not learned who these soldiers were, I uncovered a key piece of evidence that may explain why these Confederates wandered into the lens of history. This information challenged assumptions I had about these soldiers and how I look at this photograph today.

Researching photographs of Civil War soldiers has been a passion since I began collecting them in the late 1970s. Time and patience, and trial and error, have led to exciting and successful identifications and some sobering disappointments. One critical component of my research methodology is to take the image in front of you at face value when identifying the subject in an image. Is the uniform correct? Does the age of the soldier correspond to the subject? Can you confirm eye color with enlistment data?

In his groundbreaking work, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time, William A. Frassanito used geographic contours, along with existent rocks and buildings to align Brady’s 1863 photographs to contemporary locations. Frassanito discovered through this method that the three prisoners were photographed just feet from the door of the Lutheran Seminary.

For this study, I accepted Frassanito’s conclusion about the location. I approached this photograph assuming the three individuals, while clearly posed, were photographed as we see them on the Seminary grounds.

Making the case for prisoners detailed on other duties

Most of the 5,000-plus Confederates captured at Gettysburg were moved north to prisoner of war camps as rapidly as U.S. military personnel could process them. However, several hundred stayed put and were employed in work and burial details, or as nurses at the various hospitals in Gettysburg.

The dating of the image of the three prisoners suggests that they were not part of the mass of Confederate prisoners processed immediately after the battle. Frassanito asserts the photograph’s date as July 15. Paul Bolcik, in his Summer 2023 MI cover story “Three Confederate Prisoners at Gettysburg: Exploring the vast void of an iconic photograph,” holds that Brady’s assistants David Woodbury and Anthony Berger could have made the image as early as July 8.

The presence of the three prisoners on the battlefield on either date indicates they were part of this group of several hundred working in some capacity.

Frassanito speculates that the three men were captured after action. However, if these were indeed stragglers captured during mop-up operations, or perhaps deserters, they would likely have been under guard. Frassanito implies that Brady’s team asked the Union guards to step outside the frame of the lens. This explanation asks us to assume about something the image in front of us fails to show.

Would not Brady and his assistants, marketing these photographs to a Northern audience want to show Confederate prisoners under guard, instead of posing on their own?

I believe that as the photographic evidence shows a lack of any soldier guarding these individuals, they were most likely prisoners of war detailed on the battlefield in some capacity. In support of this statement, the wealth of equipment displayed by the three (and carefully inventoried by Bolcik) leads to the inescapable conclusion that they had the opportunity, the time and permission to gather these essential items from the battlefield.

One can assume a Confederate prisoner of war serving on a work detail or as a nurse would have plenty of opportunities to pick over the vast quantity of discarded items left in the wake of the battle. Looking at the uniforms and equipment displayed, I agree with Frassanito, as quoted in Bolcik’s article, that all visual clues related to their uniform and equipment point to the fact that these are enlisted men, not officers or surgeons. That the backpacks, haversacks, canteens, cups and blankets are all strapped on suggests the men are ready to embark on a long journey, perhaps a prisoner of war camp or home.

Examining key documents to find their identities

I decided on a three-pronged plan of attack to find out if they were detailed as nurses:

- Examine the actual roster of nurses at the Seminary Hospital mentioned on the 2017 tour. Perhaps it would reveal an anomaly that would single out three of them and why they left sometime between July 8 and 15.

- Comb though records of the Provost Marshall operating in Gettysburg immediately after the battle. Perhaps I would find an anomaly in the mass of processed prisoners between the key dates listed above.

- Review the diary of Capt. Henry Blood. Greg Coco’s definitive book on Gettysburg in the wake of the battle, A Strange and Blighted Land, often quotes the diary of Blood, an officer in the Volunteer Quartermaster Department who oversaw clean-up operations on the battlefield. At one point, Blood notes a squad of Confederate prisoners was detailed to a hospital. Perhaps Blood’s diary included other relevant information.

My research began with a research appointment and met with the Army historian at the National Archives, where most of the documents are housed. I learned with disappointment that the Provost Marshall records concerning Confederate prisoners are interrupted by a significant gap between early June 1863 and 1864. I located one ledger with miscellaneous prisoner records, but it had a gap between the critical months of June and August 1863. I was not able to ascertain why the gaps existed. They may be the result of Provost Marshal’s office being overwhelmed after Gettysburg campaign, misfiling, or somehow gone missing.

I had hit my first wall.

The ledger containing the roster of nurses at the Seminary Hospital consumed another trip to the Archives. There are several ledgers with rosters, but only one recorded the Confederate nurses (there were 27 of them). Unfortunately, the roster was compiled on Aug. 10, 1863—almost a month after the July 8-15 timeframe I focused on. Adding to my disappointment, the roster contained no dates of when a prisoner was detailed, his final disposition, or additional information. I reviewed the military service records of all 27 men and confirmed that they did not transfer to a prisoner of war camp until well after the July 8-15 time frame.

I had hit another wall.

At my last stop, the Library of Congress, I examined Capt. Blood’s diary. His entry for July 12, 1863, is significant: “Took a squad of prisoners of war and went up to the Confederate Hospital to assist in cleaning up and to bury the dead. Found them in a suffering condition. Left ten prisoners for nurses. Thunder showers this afternoon.”

It should be noted that the “Confederate Hospital” was likely the Hospital at Gettysburg College. It contained mostly Confederate wounded, unlike the Seminary which contained mostly Union soldiers. However, both locations are within less than a mile of each other. I hoped to find more mention of prisoners and their disposition, or even some names. Captain Blood left the battlefield on July 13 for Washington, D.C., and returned to Gettysburg on July 18—missing the critical date (July 15) when the photo may have been taken and when Mathew Brady was in town. Had Blood been present, would he have noted the presence of Brady and his camera crew at Seminary Hospital?

Yet another wall.

The Oath of Allegiance theory

The sources I hoped would yield new clues did not. I was no closer to understanding the individuals in this photo than when I began. Disappointed and ready to end my research, I opted to close things out with a “Hail Mary” Google search. Typing in “Provost Marshal records” and “Gettysburg,” the search engine returned an unexpected and surprising result: An inventory of materials held by the Musselman Library at Gettysburg College including three documents concerning Confederate prisoner of war nurses.

One document caught my attention. It appeared to serve as a pass. Dated July 29, 1863, and signed by the surgeon in charge of the 2nd Corps hospital, it lists six Confederate prisoners ordered to the Provost Marshal “who desired to take the Oath of Allegiance.” Since this hospital was filled with Union soldiers, we can assume these six individuals were prisoner of war nurses.

Suddenly I had an explanation for why the three prisoners may have been in this exact spot.

Their connection to the Oath of Allegiance might answer the question of why none of these men stepped forward to identify themselves in this photograph.

To appreciate the importance of this information, I needed to understand how the government utilized the Oath during the war. Beginning in August 1862, the Lincoln Administration allowed Confederate prisoners who would swear the prescribed Oath of Allegiance to be released without further obligations. The policy changed in May 1863 by executive order which prohibited these releases unless specially authorized. What “specially authorized” meant was subject to interpretation. By August 1863 the Adjutant General in Washington published specific guidelines for releasing prisoners who took the Oath. Factors included whether the individual was conscripted and “extreme youth.” However, by October 1863, “Oath” releases all but stopped (as did most of the “cartel” exchanges of prisoners, due to Confederate refusal to exchange Black soldiers). Months later, in early 1864, the administration resumed the release of Confederate prisoners who took the Oath, but with the provision that they serve in volunteer regiments on the frontier. About 5,000 of these Confederates became so-called “Galvanized Yankees.”

The decision by a Confederate soldier to take the Oath of Allegiance had long term implications for them, and their families and friends back home. The stigma would be difficult, perhaps impossible, to remove.

Whatever motivations or inducements a prisoner captured in July 1863 had to take the Oath, doing so began a process that, if successful, would take place at a prisoner of war camp. The cases of the six prisoners listed on the Gettysburg College document played out in different ways. One signed the Oath and gained his release in February 1864. That same month, three others signed the Oath and became Galvanized Yankees. One prisoner, exchanged in 1864, did not take the Oath. And the sixth soldier gained his release in 1865 after taking the Oath under the general amnesty provision following the surrender of the Confederate armies.

This case intrigued me because the pass documents a small group of individual prisoners moving thorough Gettysburg. Considering the relatively small number of Confederates who took the Oath overall, it is an anomaly. Given their desire to end their combatant status, it stands to reason that they would not have been accompanied by guards, but simply allowed to pack up and report to the Provost Marshal’s office with the appropriate pass.

Perhaps this is precisely what Brady and company captured.

One more point: Assuming these three Confederates were nurses at the Seminary Hospital, could they have been discharged because they were no longer needed? In fact, the documents held by Gettysburg College contain two examples of 1863 passes transferring Confederate nurses to the provost marshal for this very reason. One is dated July 27 and the other July 29.

These dates are important when considering the level of activity of these field hospitals and their staffing needs. As the month of July wore on and patients expired or became ambulatory, nurses were indeed sent away. However, the Seminary Hospital operated at capacity during the July 8-15 timeframe I focused on, so it seems unlikely that three nurses would be sent to the Provost Marshal during this time because they were not needed. This leads us back to the scenario of three prisoners seeking to take the Oath of Allegiance.

Final thoughts

In his article, Paul Bolcik asked several fundamental questions about the image: “During the postwar period, as the veterans aged and debated their places in history at reunions, monument dedication ceremonies and elsewhere, no one stepped forward to claim they were one of the three men in the image. No veteran publicly recognized them as comrades. This is curious, considering the wide circulation of the image in the media.” It stands to reason that at some point one of the three individuals, their family or fellow soldiers would have said something, perhaps at a reunion or in Confederate Veteran magazine. Unless, of course, the circumstances of their being photographed captured a moment each may not have been anxious to share.

To be clear, this is a theory. I hope a future researcher may find a pass similar to the one held by Gettysburg College—signed by the surgeon in charge of the Seminary Hospital, dated during the appropriate time, sending three prisoner of war nurses to the Provost Marshal’s office. Or perhaps there is a roster, or an account in a diary or letter in an archive or a private collection that fits this fact pattern, and would help us answer the question: Will they remain forever unknown?

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Peter Miele, Executive Director of the Seminary Ridge Museum & Education Center, for his extensive help researching this article, and to Paul Bolcik for his years of scholarship that help us better understand this photograph.

References: Bolcik, Paul, “Three Confederate Prisoners at Gettysburg; Exploring the Vast Void of an Iconic Photograph,” Military Images (Summer 2023); Brown, Retreat from Gettysburg; Coco, A Vast Sea of Misery; Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land; Dorris, Pardon and Amnesty Under Lincoln and Johnson; Frassanito, Gettysburg, A Journey in Time; National Archives.

Paul Russinoff of Baltimore has been a passionate collector and researcher of photographs from the Civil War since elementary school. He has been a subscriber to MI since its inception. His profile of Maj. Benjamin F. Watson, “A Savior of the Capitol,” (MI, Spring 2021) received an Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award. Paul is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.