By Steve Procko

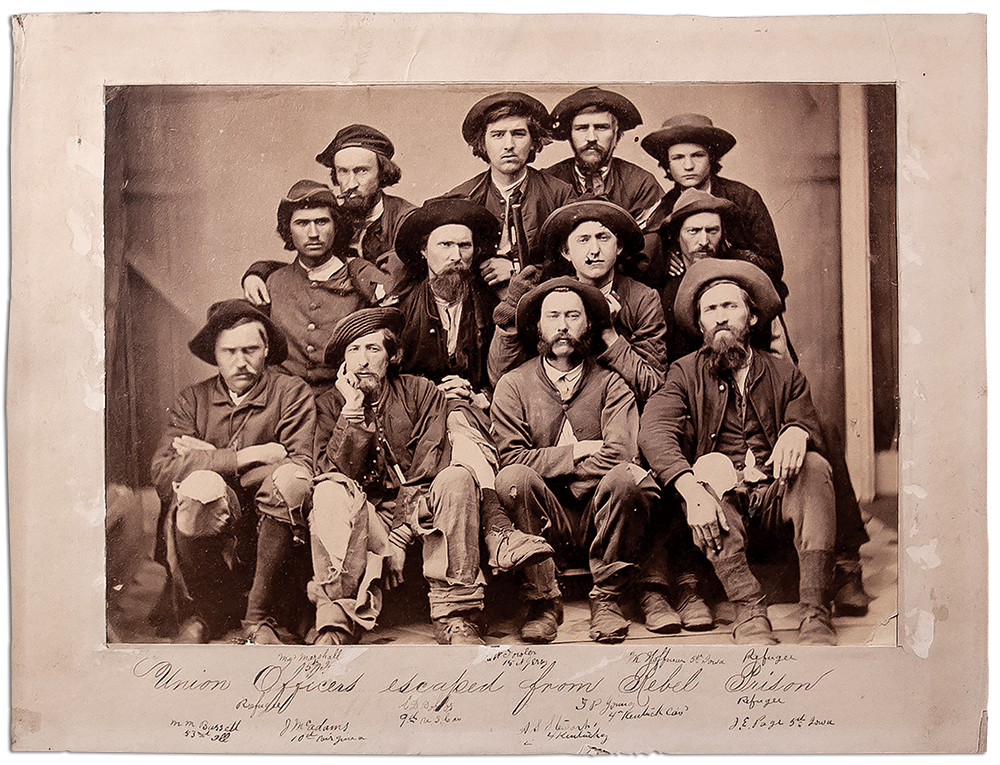

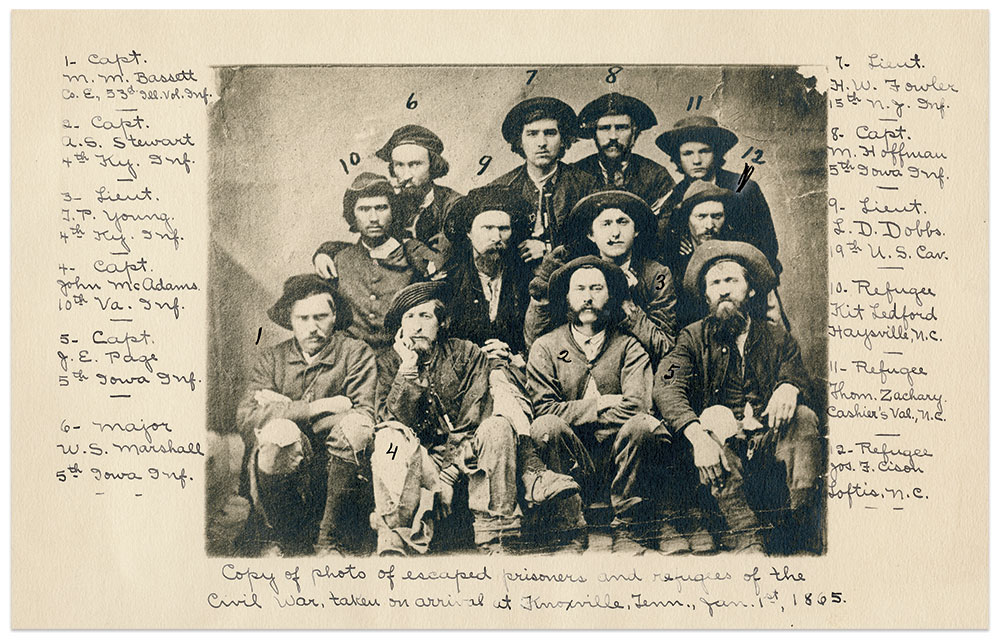

A text message from fellow Civil War enthusiast Sam Houston with a photograph of 12 ragged men appeared in the middle of our conversation about the chaotic conditions in the North Georgia mountains during the Civil War.

I texted back: “That’s an amazing image—who are they?”

“This is a photo taken by the Union Army in Knoxville. David Ledford is identified in this group of Union officers who had escaped from a Confederate Prison in S.C. David had guided them through the mountains. David is 2nd row far left,” replied Houston.

David Ledford was Sam Houston’s second cousin, Sam himself turned out to be a neighbor living just over the mountain from me in North Georgia, proving once again that history can be found around just about every bend. Sam then texted that David had been killed on Dec. 11, 1864 by Abbott’s Scouts while helping Union prisoner of war officers escape.

David Ledford was Sam Houston’s second cousin, Sam himself turned out to be a neighbor living just over the mountain from me in North Georgia, proving once again that history can be found around just about every bend. Sam then texted that David had been killed on Dec. 11, 1864 by Abbott’s Scouts while helping Union prisoner of war officers escape.

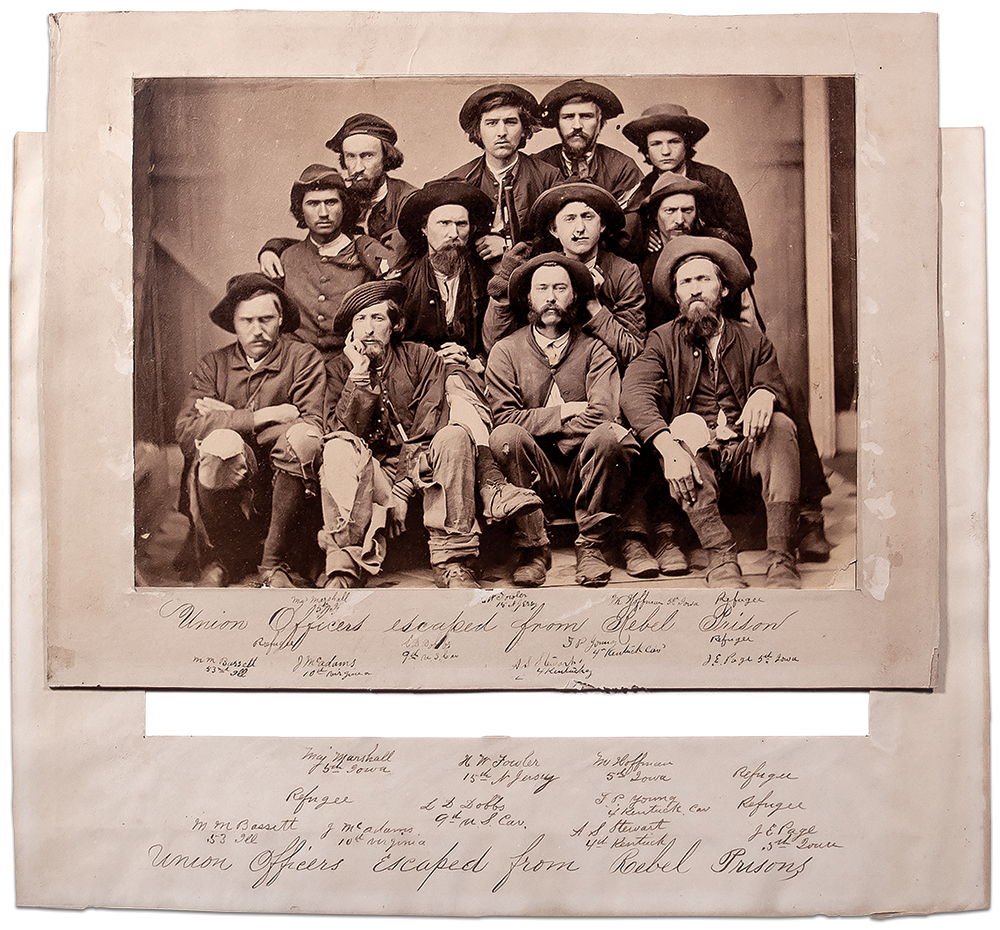

The back of Sam’s photograph had a “LC Fine Arts Division” stamp, which led me to the Library of Congress.

“Group of Union officers and their guides who escaped from Confed. prison at Columbia, S.C., in the fall of ’64…,” proclaimed the description on the Library of Congress (LOC) website page. Handwritten in pencil on the mounting board were the names of the men.

I started tracking each man, and soon had a complete list of their first and last names, military records, dates of birth and death.

Though I had never seen the picture before, I found that the image had been published many times. I identified five different first-generation copies of the photograph, and at the end of this sleuthing journey, discovered a single original print.

I also discovered that the photograph’s identification has been obfuscated almost from the moment it was made.

Provenance of the Library of Congress print

The LOC description notes that the image, an albumen print measuring about eight-by-10 inches, was donated by Mrs. Louise Sloan Ernst in 1944. Her genealogy reveals that her father, Matthew Morrison Sloan, and a cousin, Dr. William T. Sloan, had lived in Peoria, Ill.

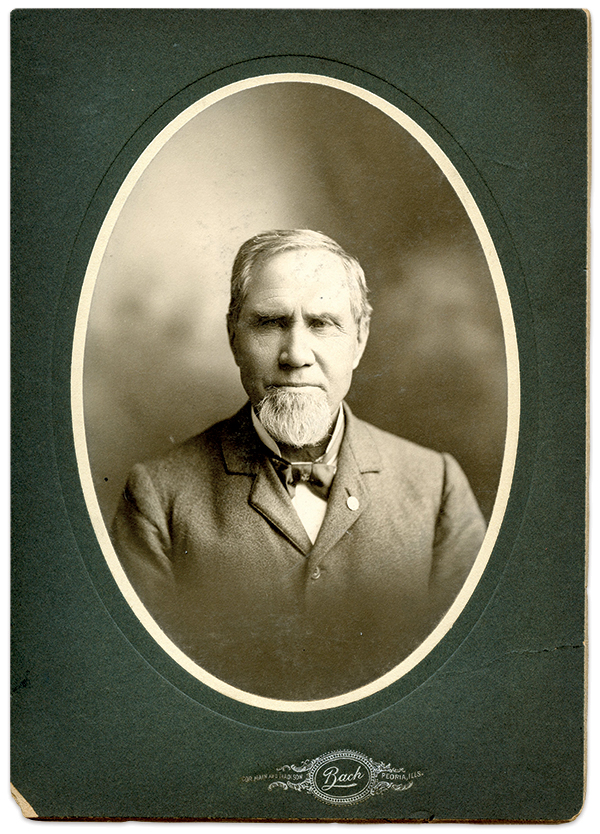

Mark M. Bassett, the man pictured in the bottom left of the image, also lived in Peoria. He served as a first lieutenant in Company E of the 53rd Illinois Infantry, and received a promotion to captain, but never mustered at this rank. Dr. Sloan proved to be Bassett’s physician, and wrote an assessment of his health for his Soldiers Pension Application. He signed Bassett’s death certificate in 1910.

Of the men pictured, Bassett was held prisoner the longest. Captured in Jackson, Miss., in July 1863, he was one of 109 men who famously escaped through a tunnel at Libby Prison in Richmond, Va., in February 1864. He was recaptured a few days later. After the war, Bassett became an attorney, served a term in the Illinois legislature and two more in the state senate, and finally as a probate judge in Peoria.

Bassett confirmed his ownership in an account about his prisoner of war experiences. Three weeks before his death in 1910, the Peoria Herald published his story and the image. Bassett stated, “I have a photograph of twelve ragged men with determination strong in their faces, taken at Knoxville, Tenn., January 1, 1865.” Bassett’s widow, Annie, had the same account; its authenticity sworn to by two witnesses, entered into the minutes of the Illinois General Assembly.

I concluded that the LOC image originally belonged to Bassett. who in the last years of his life had given a copy to his personal physician. Multiple copies of it can be traced to Bassett’s original.

Other copies confirm the original owner and surface a misidentification

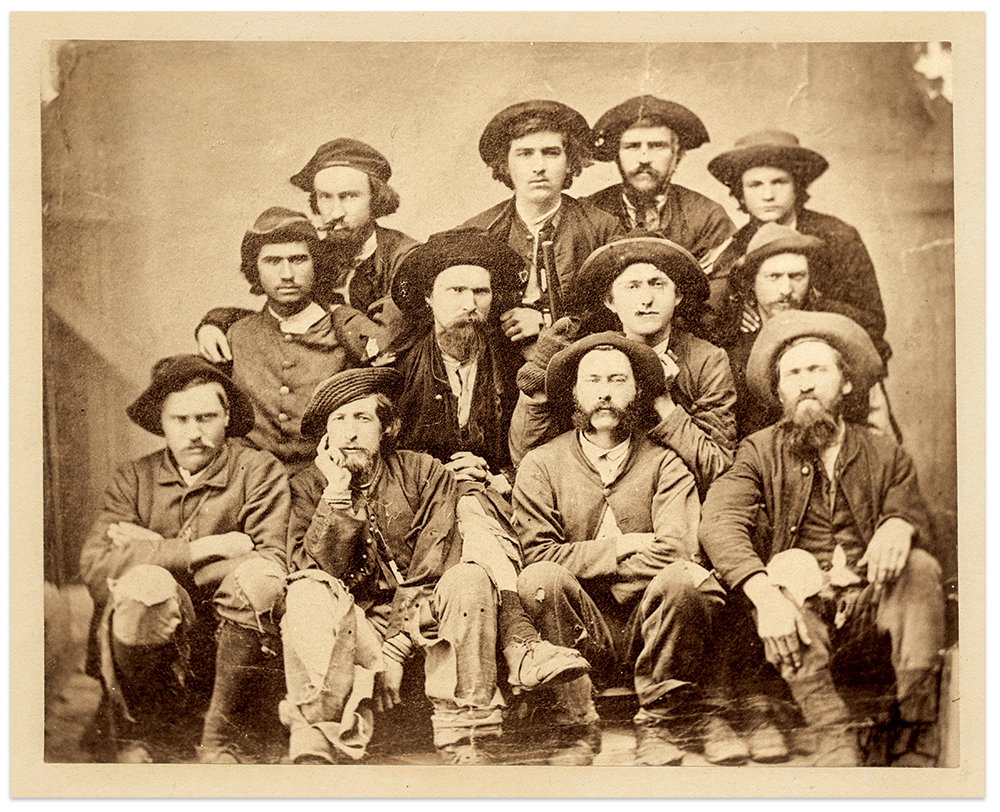

One of the copies can be found about 160 miles northeast of Peoria in the Chicago History Museum. It identifies the men as members of Morgan’s Raiders held at Camp Douglas. This copy is attributed to Daniel F. Brandon, who routinely photographed prisoners there. Exactly when the museum acquired the image is not recorded. But my research indicates it had been identified this way since the early part of the 20th century. This historical self-perpetuating error has resulted in the incorrect identification being published uncounted times.

There is a bit of irony in the misidentification. When Bassett enlisted in February 1862 as a sergeant in the 53rd, one of the regiment’s first assignments was guard duty at Camp Douglas during its conversion into a prison for Confederate prisoners.

The image has another Chicago connection. In 1888-89, wealthy Chicago candy manufacturer and history buff Charles Günther purchased Libby Prison. Workers in Richmond disassembled the old building brick-by-brick and loaded it onto a train for the trip to the Windy City, where it was reassembled. It became a kitschy Civil War museum.

I located two letters discussing the image displayed at the Chicago Libby Prison Museum. One was written to Bassett in 1897 by the museum manager and secretary of the Libby Tunnel Association, Robert C. Knaggs, a veteran of the 7th Michigan Infantry who had been captured at the Battle of Gettysburg and imprisoned at Libby at the same time as Bassett. The other was written in 1911 by Annie Bassett to Thompson Roberts “T. R.” Zachary, the boy in the upper right of the image.

Annie explained, “Mr. Bassett had sent with the group photo to be exhibited in Chicago in Libby Prison which had been removed to that city and was for years a center of attraction to patriotic people. When it ceased to be such—or when the property it occupied changed hands, the copy of the picture with the page of explanation was returned to him and he gave the copy to someone else.”

When the Libby Prison museum closed in 1899, the Chicago Historical Society (CHS) acquired a large portion of the bricks. In 1920, the CHS purchased Günther’s Civil War memorabilia. Today the CHS is known as the Chicago History Museum.

In 2022, the Chicago History Museum updated its identification of the image after I presented the facts contained in this article to them.

I discovered a third copy of the image in the Peoria Public Library. One of the librarians believes the image was part of a donations of a grouping of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) photos.

This print displays the characteristics of a platinum print. It is housed in a Venard Studios folio. The Bach photographer who made a portrait of Bassett late in his life later worked at Venard. Based on the studio’s history, Annie likely had this copy-print made about 1916.

The back of the print has a handwritten note “Photo File: GAR.” Bassett belonged the Peoria post. It also identifies the men. My research determined that this copy that correctly identified all of them.

The LOC, CHS and Peoria Library prints are all copies made from the same original, displaying the exact same creases, damaged emulsion and other marks. All three point to Bassett’s ownership.

Bassett also gave a copy of the photo to T.R. Zachary about 1884. The two men corresponded with each other until Bassett’s death, and Annie continued the correspondence. Zachary’s great-granddaughter, Jane Gibson Nardy, shared his letters with me saying “We are a family of pack rats.” Thank God for that.

The mysterious National Archives negative

The National Archives collection includes a version of the image. It is a glass plate copy negative of likely an original print contained within an oval matte. The image is titled “Photograph of a Group of Confederate Prisoners” with no additional context. The title is ambiguous. It could be interpreted that the sitters were Confederates prisoners or Union prisoners in the Confederacy. This ambiguity is resolved by words scratched into the emulsion of the negative: Rebel Prisoners. It is fair to state that the individual responsible for this misidentification did not know the backstory of the men pictured.

This negative was part of the purchase made by the War Department Records Office in July 1874 and April 1875 of almost 6,000 negatives from the Mathew Brady studios. How it ended up here is a mystery. The National Archives has no further information.

The Hoffman print points to the date and the photographer’s identity

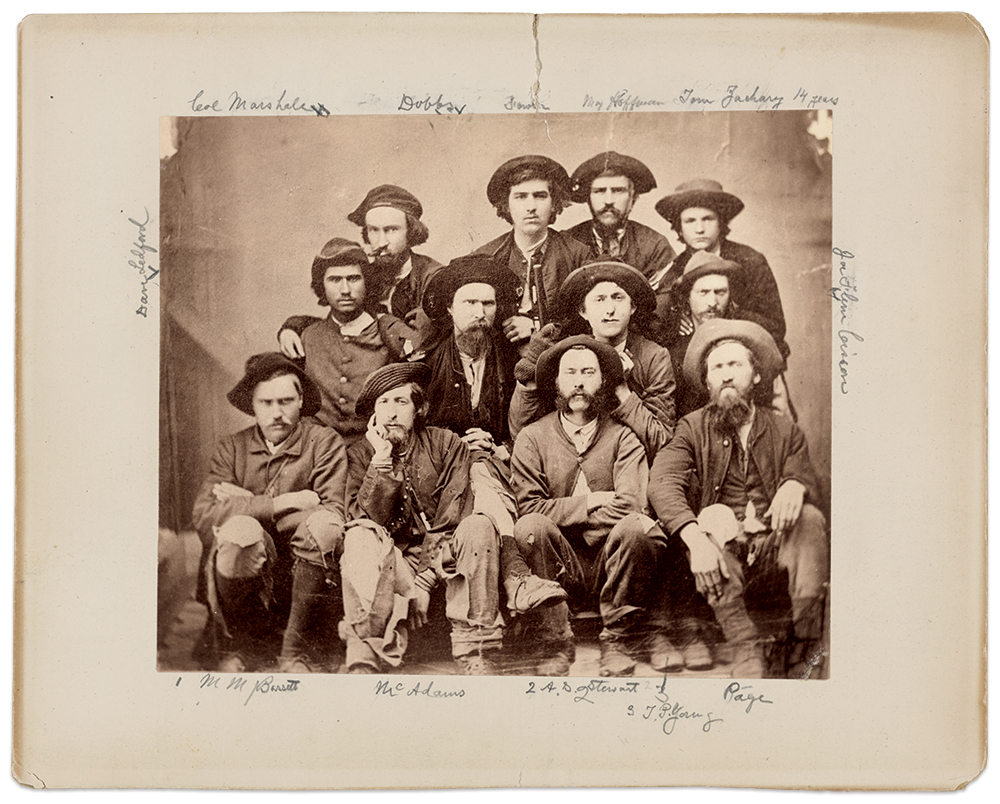

I discovered another version at the Union County Historical Society in Elk Point, S.D. Made from an original print, it is a first-generation copy donated in 2011 by descendants of 1st Lt. Michael Hoffman of the 5th Iowa Infantry. He is pictured in the back row, third from the left. Hoffman had settled in Elk Point, Dakota Territory, after the war.

More than a year later, I located Hoffman’s great-granddaughter living in Bend, Ore., who is the current owner of Hoffman’s original albumen print.

The Hoffman version is significantly different from the Bassett print. It displays none of the identifying marks on the Bassett print and shows a wider view of the studio setting, with a vertical plumbing pipe visible on the right of the frame.

It also shows the matte, which includes handwritten identifications of all the soldiers. The guides are only identified as refugees.

The Oregon descendant also owns the diary Hoffman carried through the war and articles he wrote for the Union County Courier. A nearly complete transcript of this diary was donated to the Union County Historical Society. The diary establishes the men sat for the portrait on Jan. 2, 1865, not January 1 as noted in the LOC and Bassett versions. As Bassett’s date was based on his recollections 44 years after the event and the LOC followed Bassett’s suit, I believe Hoffman’s diary to be more accurate.

Hoffman’s writings reveal that the men crossed over Union lines during the morning of January 1 and sat for the portrait the next day.

“We were now in Union territory, and only nine miles to Sweet Water (sic), a station on the Chattanooga & Knoxville railroad,” Hoffman wrote, “We arrived at the station at 2 o’clock p.m., Jan. 1, 1865, finding the place guarded by a company of Union soldiers…We waited at the station until about 4 o’clock, when the passenger train came along.”

Hoffman continued that they arrived in Knoxville about dark and were housed that night on cots in the soldiers’ hospital, Asylum General Hospital. The building still stands today and houses the Lincoln Memorial University’s School of Law.

Hoffman noted that the next morning, January 2, before they left the soldiers’ hospital that staff “gave us an entire new suit of blue soldier clothes, but before discarding our old ones we put them on and went up town in search of a photographer. No caravan in passing through the streets would have excited any more curiosity than we did. There were twelve of us who had our picture taken in the group, four of our party for some reason or other not being with us.”

They first appeared at the headquarters of the Provost Marshal, Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Carter. Each man’s information, plus where and when they had been captured and escaped, was handwritten on official letterhead. A telegrapher transmitted the names to Washington, D.C., that evening.

I believe the photographer who made the image was most likely Theodore M. Schleier. His studio on Gay Street, Knoxville’s main thoroughfare, was located next door to Carter’s headquarters. Schleier advertised his new studio when it first opened at the beginning of 1864 as “Headquarters for Pictures … next to General Carter’s headquarters.” A large sign, “T.M. Schleier Picture Gallery,” hung from the exterior of the building. The studio, located on the third floor, featured skylights providing necessary light to expose a wet plate collodion negative.

Schleier, a German immigrant and daguerreian pioneer, enjoyed a political relationship with The Knoxville Whig Editor William G. “Parson” Brownlow, who took office as governor of Tennessee on April 5, 1865. Schleier helped the Brownlow political machine connect to Knoxville’s German community. Parson’s son, Col. John Bell Brownlow, succeeded his father as editor.

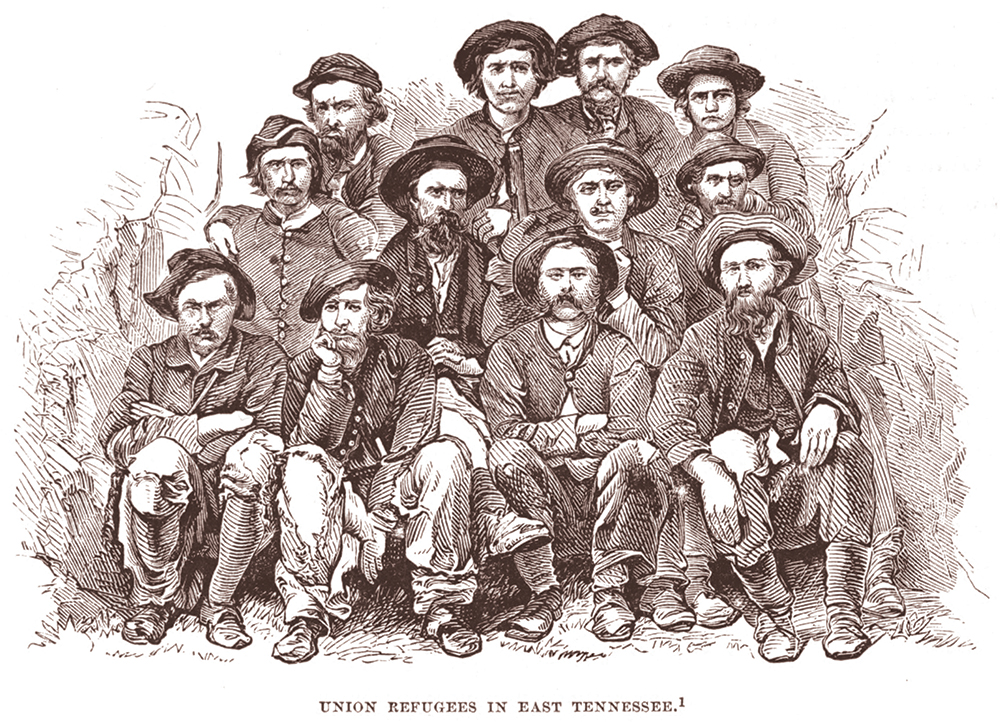

In May 1866, the Governor and his son welcomed the prominent historian, author, artist and engraver Benson J. Lossing to town. Lossing toured the south collecting material for his three volume book series, History of the Civil War in America. The third volume, published in 1868, included an engraving made from the image. The caption and a related footnote misidentified the group as “Union Refugees in East Tennessee” and noted that “This is a careful copy of a photograph presented to the author, at Knoxville, in which is delineated a group of the returned refugees, at the time we are considering. They consisted, in a large degree, of young men belonging to the best families in East Tennessee. Their sufferings had been dreadful. Their clothing, as the picture shows, was in tatters, and at times they had been nearly starved. Yet they held fast to hope, and resolved to save their country if possible.”

and final volume of Benson J. Lossing’s History of the Civil War in America. Internet Archive.

After the book’s publication, Bassett commented on the engraving, “procured no doubt, from the photographer in Knoxville, Tenn.” Hoffman added, “Mr. Lossing was off his base.”

Confirming identities of the men and the story of the escape

I turned my attention to the identities of the officers and men in the photograph using the research described here, plus military service files, genealogical records and other documents, and interviews. I confirmed the names of all of them with one exception: David Ledford, the second cousin of my North Georgia neighbor Sam Houston.

David Ledford, a deserter from Company D of the 2nd North Carolina Mounted Infantry, had died three weeks before the men posed for the portrait. On Dec, 11, 1864, according to two Union officers, Confederates belonging to Abbott’s Scouts killed him. This unit, commanded by Capt. William R. Abbott, served in Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn’s Brigade in the Department of Western Virginia and East Tennessee.

Hoffman’s account revealed the name of the man: Kit Ledford. He was Julius Ketron “Kit” Ledford, one of David’s cousins in an extended family living in and around Hayesville, N.C. Kit and enlisted with David in Company D of the 2nd, and also deserted.

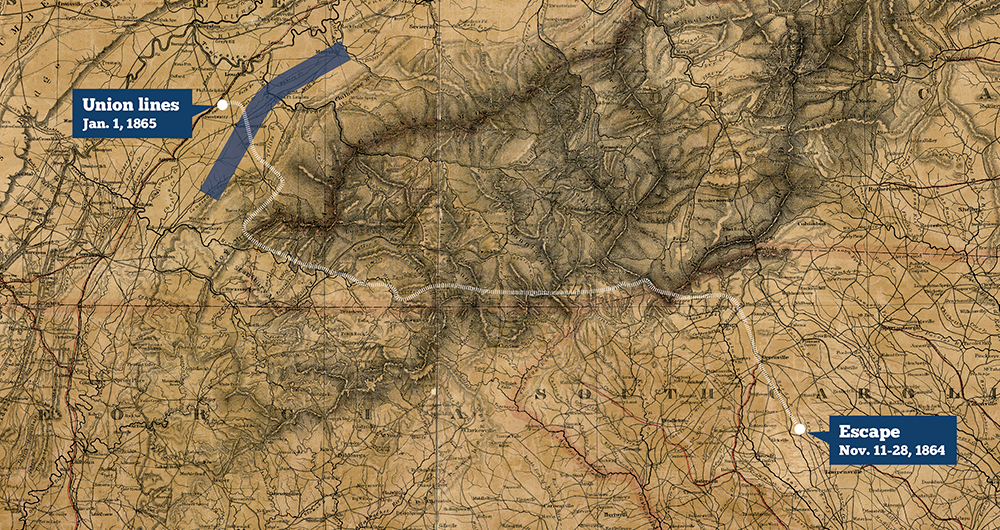

Triangulating multiple accounts of the soldiers and men resulted in the following narrative: Eight of the officers escaped from Camp Sorghum, located west of Columbia, S.C., between Nov. 10 and 28, 1864. One of them, Lemuel D. Dobbs, escaped with a Union private from the Richland County Jail in Columbia.

The officers who escaped from Camp Sorghum did so in groups as large as nine, and some alone. The group of nine, which included Mark Bassett, Alfred Stewart and Thomas Young, split up into three smaller groups to become less visible to those pursuing them. All the escapees followed a similar route north, helped by enslaved people and Union sympathizers along the way. Two of the guides, Flem Cison and T.R. Zachary, aided some of the officers on the trek through the rugged North Carolina mountains. On December 28, these small groups surfaced near Hayesville, where several members of the Ledford family helped them. They met Kit Ledford here for the first time.

Shortly after, they crossed Union lines and on New Year’s Day 1865 at Sweetwater, Tenn., caught a train bound for Knoxville, and arrived around sunset. They had made it, prisoners of war no more.

When they posed for the group portrait the next day, Hoffmann recalled that several of the escaped officers could not be found. The list made by Brig. Gen. Carter at the Provost Marshal’s headquarters includes the names of 16 soldiers, seven fewer than appeared in the image.

When Theodore M. Schleier exposed the negative that day, his resulting image pictured a dozen men who captured freedom.

References: Mark M. Bassett pension file, National Archives; Peoria Herald, May 31, 1910; Journal of the Senate of the 47th General Assembly of the State of Illinois, Senate Resolution No. 75, May 16, 1911; Levy, To Die in Chicago Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862-1865; Illinois Adjutant General’s Report, Regimental and Unit Histories, Containing Reports for the years 1861-1866; Ramstead, A True Story and History of the Fifty-third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry Its Campaigns and Marches; Meyer, William B., “The Selling of Libby Prison,” American Heritage; Vol 45, No 7 (November 1994); R.C. Knaggs to Capt. M.M. Bassett, April 7, 1897, Peoria Historical Society; Annie Bassett to T. R. Zachary, Sept. 4, 1911; Meyer, William B., “The Selling of Libby Prison,” American Heritage; Vol 45, No 7 (November 1994); Discussion with Chicago History Museum Senior Vice President John Russick, June 29, 2022; Union County Courier, Elk Point, Dakota Territory, May 7, 1896; Provost Marshal Samuel P. Carter ledger records and telegram posts, National Archives, courtesy of Dr. Lorien L. Foote, author of The Yankee Plague: Escaped Union Prisoners and the Collapse of the Confederacy; “Fugitive Federals: A Digital Humanities Investigation of Escaped Union Prisoners” ncph.org/project/fugitive-federals-a-digital-humanities-investigation-of-escaped-union-prisoners/; Knoxville Whig, Jan. 9, 1864, and May 23, 1865; Peoria Herald, May 31, 1910; Union County Courier, May 7, 1896; Welch, An Escape from Prison during the Civil War—1864; Gordon, The Last Confederate General: John C. Vaughn and his East Tennessee Cavalry.

Steve Procko is an Emmy-award winning director. His first book, Rebel Correspondent, was published in 2021. His second book Captured Freedom, which tells the complete story of the photograph featured here, made its debut in the summer of 2023. This story is an adaptation from the book. Learn more at CapturedFreedom.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.