By Jack Hurov, with an image and artifacts from the Author’s collection

Late in the afternoon on July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg, Nathaniel Bryant Colman of the 17th Maine Infantry knelt over his open apothecary kit. The 29-year-old Hospital Steward carefully reviewed each bottle and vial. He especially noted the location of Monsel’s Solution of Iron, used to stop bleeding.

Compounding medicines, placing them in their appointed niches in his kit, and rolling and replenishing bandages had, by now, become familiar routines to Colman. Yet, despite all his training and field service, he and the regiment’s other medical officers were ill-prepared for what they were about to encounter in the twilight hours ahead.

The son of prosperous farmers, Charles Milton and Mary Polly Colman (née Crooker), Colman was born on Oct. 13, 1833, in Vassalboro, Maine. Located on the east bank of the Kennebec River, Vassalboro is about midway between Augusta and Waterville, where patchworks of rich farmland lay interspersed among stands of yellow birch, sugar maple, and red oak. The fifth of 10 children, young Nathaniel likely kept busy with farm work, and bringing surpluses of lumber, livestock, dairy products, potatoes, apples and hay to local markets.

As a young man, Colman received what today might be called a liberal arts education while attending Waterville College (later Colby College). He transferred to Princeton in the fall of 1860, but returned home in the spring of 1861, upon learning of his brother Henry’s death.

With the outbreak of the civil war, Colman’s education took a notable turn. Perhaps recognizing the severe shortage of qualified medical personnel serving in the burgeoning volunteer army, he entered the Medical School of Maine at Bowdoin College in February 1862. After he completed a 16-week course of instruction in anatomy and physiology, pharmacy, surgery and chemistry, he began his post-graduate training at the Portland, Maine, School for Medical Instruction.

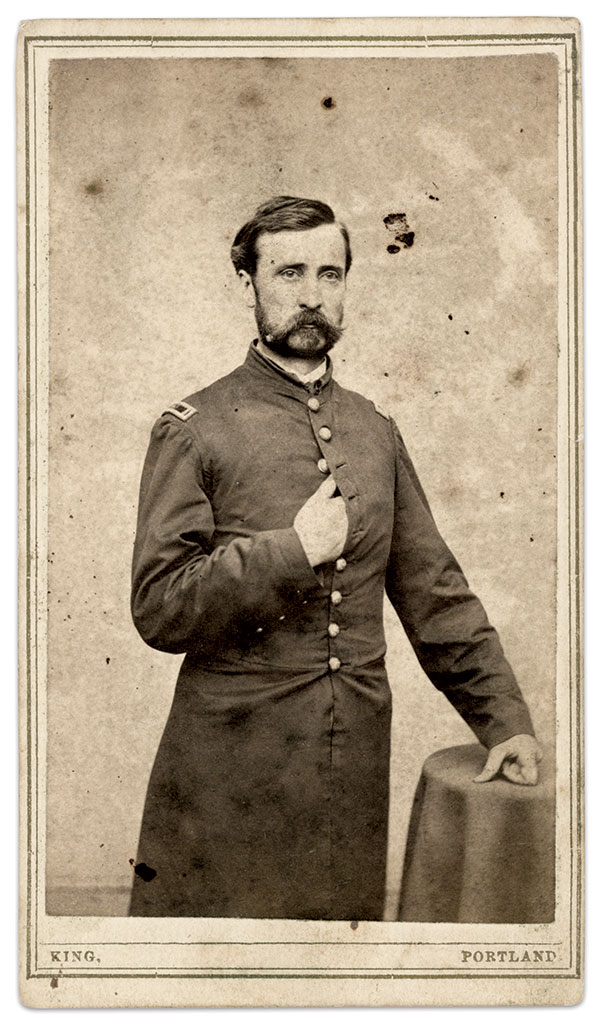

Under typical circumstances, Colman would spend the next three years training under the direct supervision of a licensed physician. However, these were not typical times. Perhaps swept along with peers and mentors by a patriotic tide, Colman left school in mid-August. He enlisted in the 17th, then organizing at Camp King in Cape Elizabeth, and was assigned to the regimental staff as a Hospital Steward.

Less than a year later, Colman and his comrades found themselves at Gettysburg.

Combat in The Wheatfield

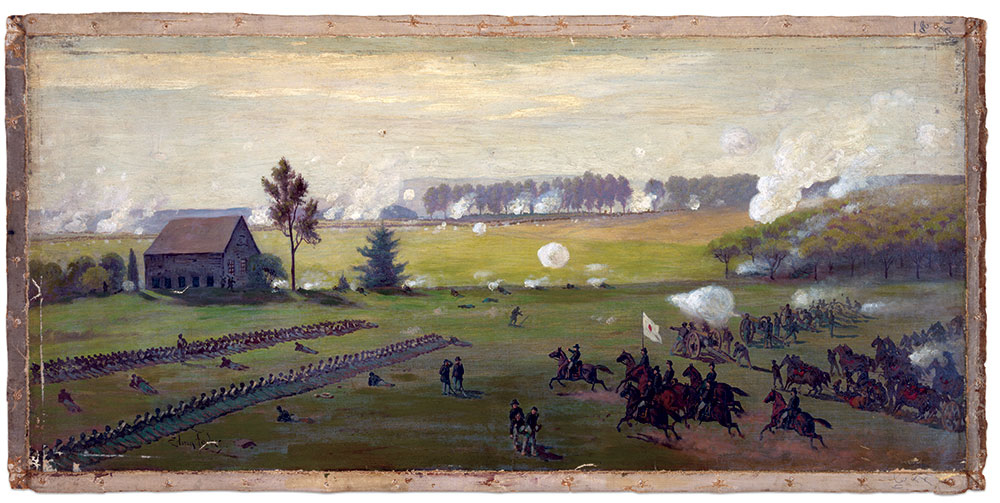

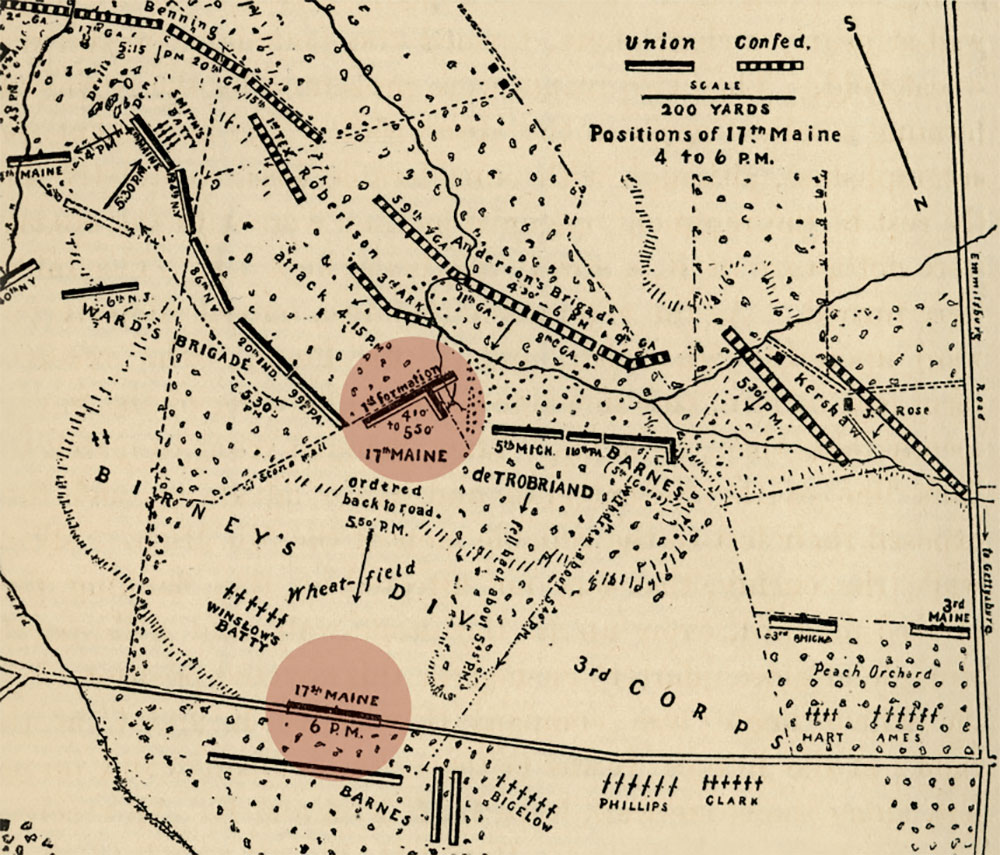

At about 4:00 p.m. on July 2, 1863, Col. Regis de Trobriand received orders to move his brigade, consisting of the 17th, supported by the 5th Michigan, 40th New York and 110th Pennsylvania infantry regiments, into a gap in the left flank of Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ precariously overextended Third Army Corps. The 17th formed along a stone wall at the southwest corner of The Wheatfield and planted its colors. Standing its ground for almost three hours, the regiment doggedly repelled successive, determined attacks made by elements of three Confederate brigades. Depleting their ammunition, the boys gathered the unexpended cartridges of the fallen. The 17th’s casualties remained on the field, and were not removed to relative safety, until 7:00 p.m. when the area was consolidated by Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s division of the Second Corps.

Of the 350 Pine State boys of the 17th present for duty that afternoon, 132 (38 percent) became casualties holding the left flank of the federal line. Given the overwhelming number of wounded soldiers requiring care, the best Colman could do was apply a dressing to control bleeding, and perhaps offer some form of pain management, until his men received definitive care from the regimental surgeons. Whether Colman assisted his wounded comrades at a forward aid station or at the Third Corps Hospital, located some two miles east near the Jacob Schwartz farm, is unknown.

Of the 350 Pine State boys of the 17th present for duty that afternoon, 132 (38 percent) became casualties holding the left flank of the federal line. Given the overwhelming number of wounded soldiers requiring care, the best Colman could do was apply a dressing to control bleeding, and perhaps offer some form of pain management, until his men received definitive care from the regimental surgeons. Whether Colman assisted his wounded comrades at a forward aid station or at the Third Corps Hospital, located some two miles east near the Jacob Schwartz farm, is unknown.

On July 3, the 17th numbered less than half its strength from the day before. Its 150 troops took up a position along the Taneytown Road in support of Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday’s division. The regiment, opposite Col. Porter Alexander’s Confederate batteries, suffered an additional dozen casualties during a two-hour artillery bombardment before Pickett’s Charge.

On July 4, the regiment joined in the pursuit of Gen. Robert E. Lee and suffered an additional casualty in the battle of Wapping Heights on July 23. It was here that Colman penned this date and “Manassas Gap, VA” on a fragment of ledger paper to which he had attached a four-leaf clover.

Maybe he felt lucky to have survived the ordeal at Gettysburg.

Promotion

A few months after he picked a lucky clover, Colman advanced to assistant surgeon. On November 21, two days after President Lincoln delivered a brief address at the dedication of the Soldiers’ Cemetery in Gettysburg, Colman received his first lieutenant straps. In the absence of contrary evidence, Colman may have negotiated, at the time of his enlistment the previous summer, his being considered for promotion to regimental assistant surgeon, should a vacancy open. Certainly, his 15 months service as a Hospital Steward made him an ideal candidate for advancement.

The following month, with the 17th in winter quarters at Brandy Station, Colman was detached from his regiment to care for the sick of the 3rd Maine Infantry, stationed in Washington, D.C. He paused from his arduous duties on Christmas Eve to write to his younger sister Vesta. “I have been detailed to take charge of this reg’t for a short time, while Dr. [Thaddeus] Hildreth of Gardiner goes home on a ‘leave of absence.’”

Colman confirmed that he was in good health and apologized for an anticipated months-long delay visiting home, due to his increased responsibilities. “I am alone in this regiment. Had between fifty and sixty sick ones to doctor this morning.” Colman also confided his need to exercise caution in his dress when having his picture taken for family at home. And he good-naturedly wished for more family photographs, having received but a single picture. Signing his letter on Christmas Day 1863, Colman left no doubt where his loyalties lay: “Very Affectionately Yours for our Country.”

Based on regimental hospital returns from the 3rd Maine for October 1863, Colman may have seen recuperating patients in as many as four widely separated Washington hospitals: Third Division (Camp Stoneman), Carver, Finley and St. Elizabeth. Small wonder he made affectionate reference to his horse, “Jenny Lind” in his correspondence to Vesta, adding that he rode most of Christmas Eve afternoon.

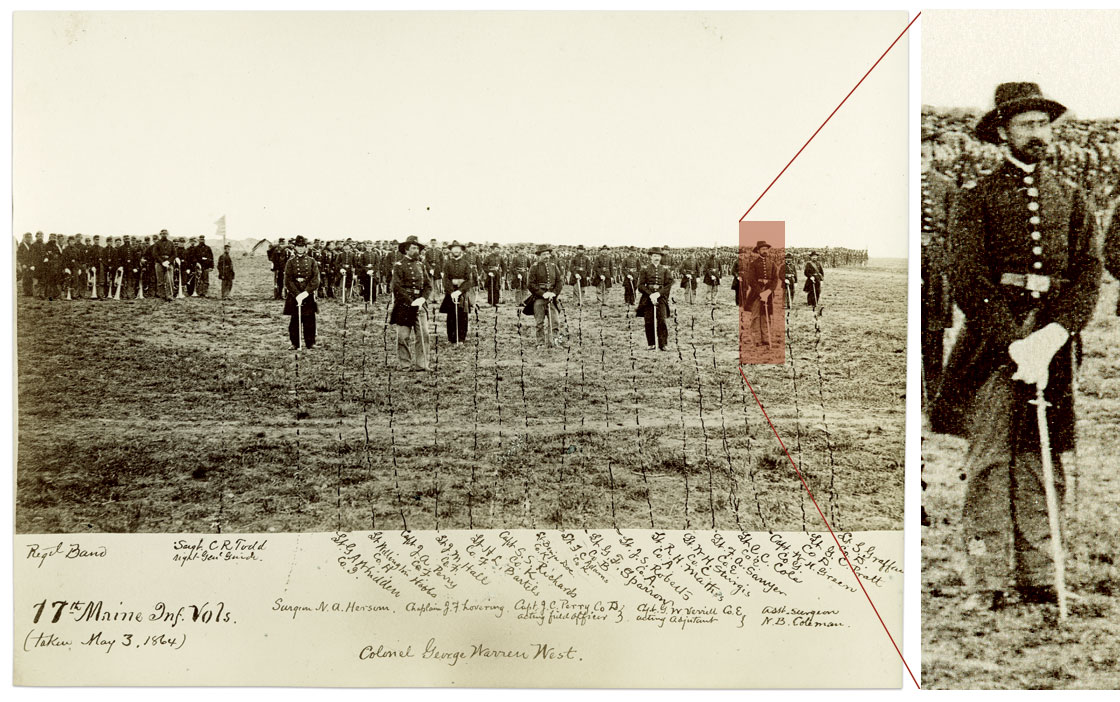

Whether Colman returned home to visit family in the spring of 1864 is unknown. However, he rejoined the 17th before the beginning of the Overland Campaign in early May. By this time, the regiment had increased to about 500 men due to returned convalescents and new recruits.

Colman had his hands full during the campaign as the 17th suffered significant casualties as part of the Second Corps in The Wilderness, the Po and North Anna Rivers, Cold Harbor and the Battle of Petersburg. The regiment went on to participate in early 1865 operations at Hatcher’s Run and Weldon Railroad.

Colman remained with his command until mustering out on June 4, 1865, at Washington.

Postwar

Like many of his generation whose vocations and studies were interrupted by the war, yet fortunate to return to civilian life physically unharmed, Colman entered the Medical Department of Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., and obtained his professional degree in 1865. The following year, he wed Leonora Wilson of Gorham, Maine, and the couple settled in Portsmouth, N.H., where Colman practiced until 1873.

Like many of his generation whose vocations and studies were interrupted by the war, yet fortunate to return to civilian life physically unharmed, Colman entered the Medical Department of Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., and obtained his professional degree in 1865. The following year, he wed Leonora Wilson of Gorham, Maine, and the couple settled in Portsmouth, N.H., where Colman practiced until 1873.

Perhaps wishing to be closer to family living in warmer climes, the couple moved to northern California in 1878, where he practiced in San Francisco. In 1883, they relocated to Montesano, Wash., in the northwestern part of the state where, in addition to his medical practice, Colman participated in civic government, including a stint as mayor in 1888. In October of that year, Colman attended the dedication of the 17th Maine monument at Gettysburg. Brevet Brig. Gen. William Hobson provided an oration containing these apt lines: “The battle was fought by troops who voluntarily enlisted and who filled our ambulances and hospitals.” Veterans of the 17th were entitled to wear a distinctive badge featuring a white numeral 17 centered on a bold red diamond representing the First Division of the Third Army Corps.

Colman retired from clinical practice in 1898, and in 1900 he and Leonora retired to Santa Clara County, Calif., where he took great pride in growing orchids. Leonora died in 1920, and Colman passed on March 3, 1927, at age 94, outliving all his siblings. The couple had no children, and are buried in Los Gatos Memorial Park, San Jose, Ca.

Note: The Maine Medical Center, Portland, incorporated the Portland School for Medical Instruction and the Medical School of Bowdoin College in 1868.

References: Cavo, Anthony. “How to identify antique enamels” Antique Trader, antiquetrader.com/collecting-101/how-to-identify-antique-enamels; Coco, A Vast Sea of Misery; History & Guide to Union & Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg; Gillett, The Army Medical Department 1818-1865; Maine at Gettysburg. Report of Maine Commissioners; Stackpole Eds., Gettysburg-The Story of the Battle with Maps; Whittemore, Colby College 1820-1925: An Account of its Beginnings; American Civil War Research Database; Ancestry.com, Nathaniel Bryant Colman; Bowdoin College Catalogues, Officers & Students, Medical School Maine, Spring term, 1860, 1861, 1862; “Brief History of Farming,” mainething.com, civilwardc.org; “Hospital Returns, 3rd Me. Infy Regt.,” digitalmaine.com; Directory of Deceased American Physicians 1804-1929; “Farming in Maine, 2000-2010,” mainememory.net; Find a Grave; Historical Sketch Med. Ed. in Maine, J. Maine Med. Assoc.; Kennebec County Natural Resource Assessment, Apr., 2011; Langdon’s List of 19th & Early 20th Century Photographers; Princeton, Sixty-Three. Fortieth-Yearbook; Spring Catalogue of Officers & Students of Waterville Acad. Me., Acad. Yr. ending 1853, May 6, 1854, 1859-60, 1861; U.S. High School Lists 1821-1923 & U.S. School Catalogs, 1765-1935; Lewiston Maine Evening Journal, Jan. 13, 1898; Kennebec Journal, Nov. 16, 1904; Santa Cruz Evening News, Santa Cruz, Calif., March 8, 1927.

Jack Hurov is a MI Copy Editor. He enjoys collecting and researching American military images.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.