By Ron Maness, featuring images from the author’s collection

During a chess match, moving a knight to confront the opposing king in its initial position (King 8) can result in the knight’s loss. If well played, however, the knight’s sacrifice may yield the removal of one or more opposing pieces from the board and may even result in checkmate.

Such are the dynamics of chess.

But what if the knight is moved to King 7 before the match begins? The opposing king’s pawn would step aside, and the knight would stand face to face with the leader of its enemy.

Of course, that is not how chess is played. A match only engages the kinetic conflict between two opponents. It is devoid the causes and events leading up to the movement of the first piece.

This hypothetical chess is a metaphor for the meeting of Jefferson Davis and Caleb Huse a few days or weeks prior to April 12, 1861.

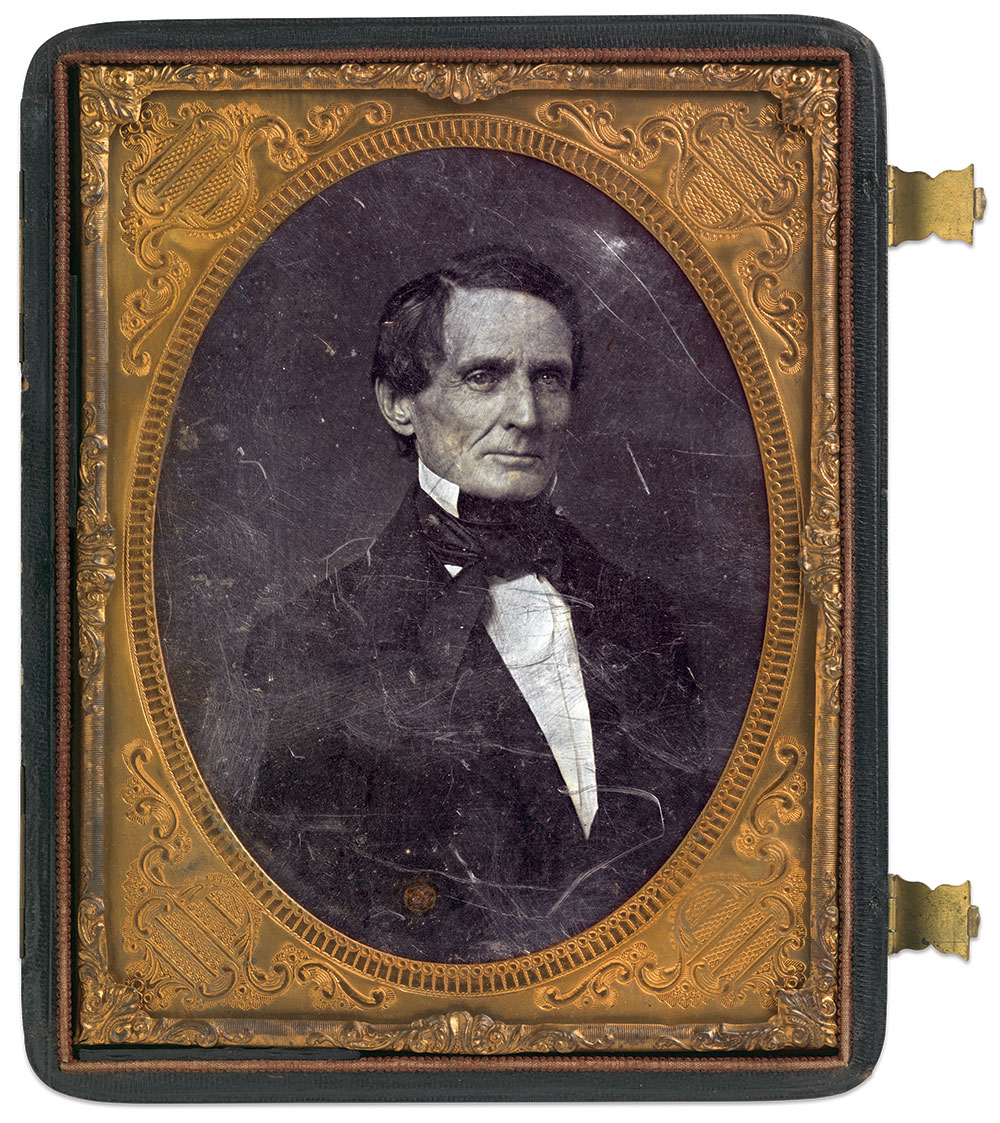

Davis, of course, was president of the fledgling Confederate States of America. He resided in Montgomery, Ala., at the time he invited Huse to meet.

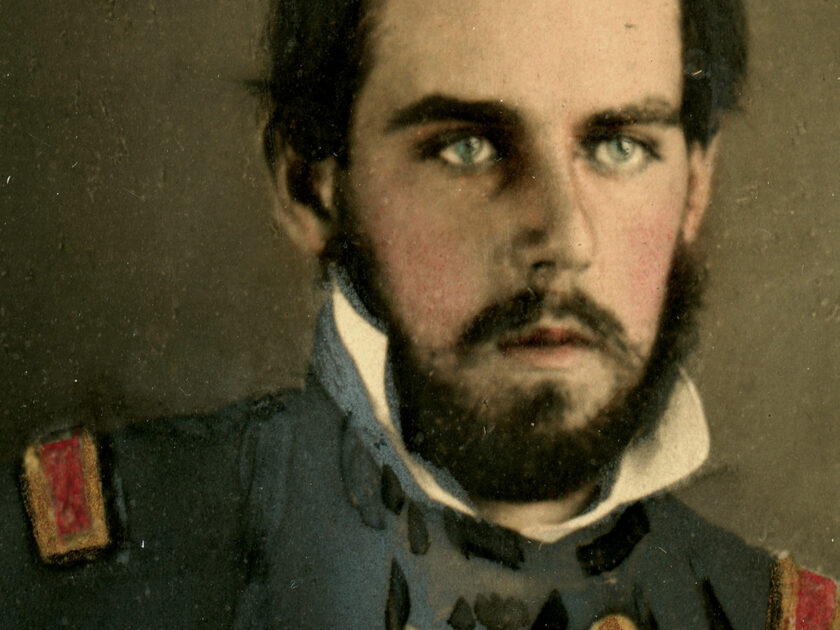

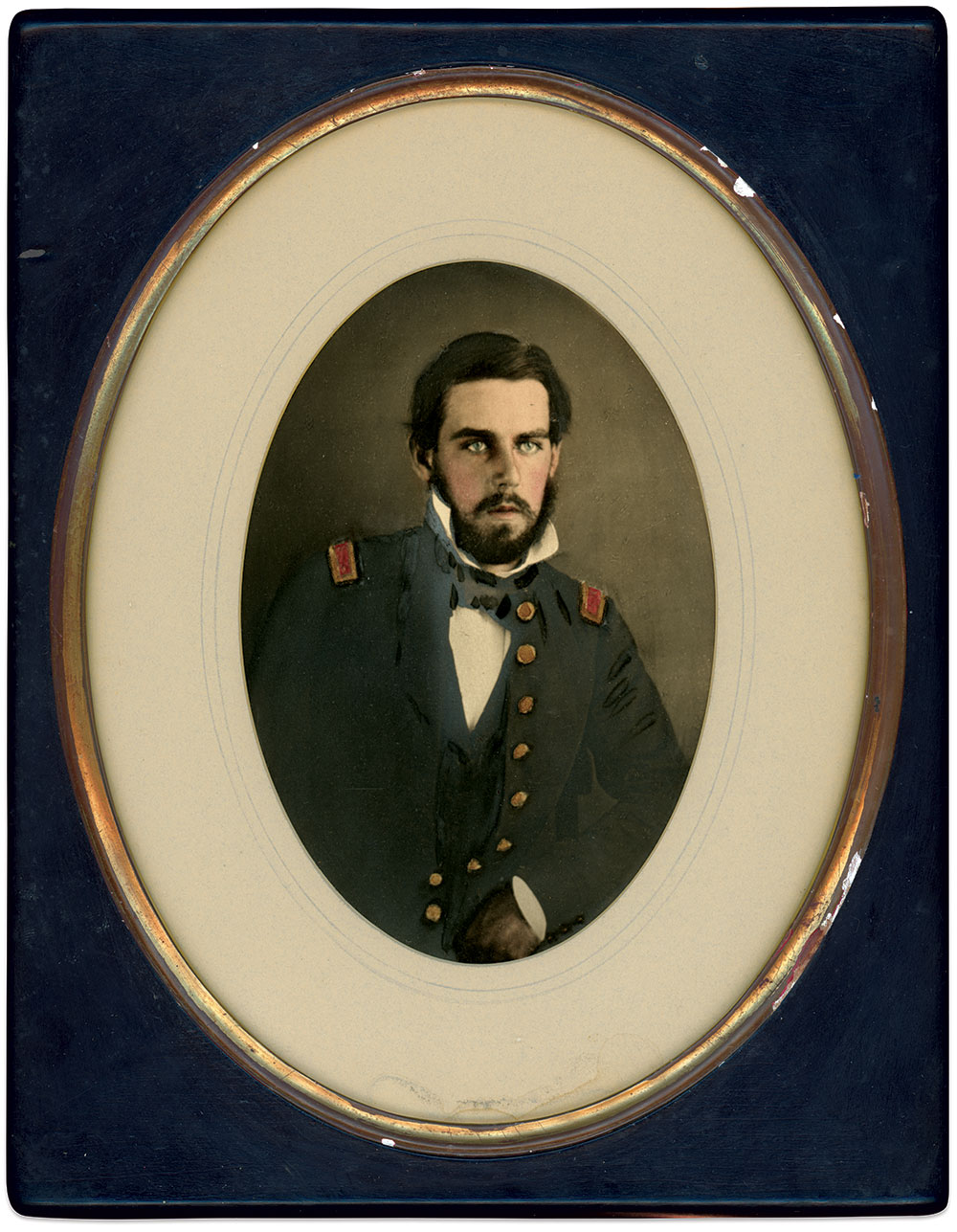

Huse, our hypothetical knight, is the focus of this narrative. Born in Massachusetts, he had graduated from West Point in 1851 and received an assignment to the 1st U.S. Artillery. Prior to his meeting with Davis, Huse had spent most of his career as an assistant professor of chemistry at his alma mater.

For all intents and purposes, Huse was a Yankee. His meeting with Davis and its outcome is perplexing. Why did he accept an invitation to meet Davis in his office, spending some hours in discussion? What message did Huse have that resulted in Davis dispatching him to Europe, as a purchasing agent of military goods on behalf of the Confederacy? What evidence of southern loyalty was presented that convinced Davis to assign Huse such an important responsibility?

The meeting between Davis and Huse does not appear to have been recorded by the Confederate president. Huse references the meeting 44 years after the event. In his 1904 Personal Reminiscences and Unpublished History, Huse comments respective to his interaction with Davis, “I do not recall any of the conversation that took place…”

We can forgive Huse that after so many years details of conversations do escape memory. However, in the very next sentence Huse writes, “Looking over a letter of four full-sized pages, and standing up with some show of irritation, he [Davis] said, I wish people would not write me advice, and he tore the letter in two…” Huse continues on in vivid detail, presenting interactions with other individuals that occurred within a few weeks of his meeting with Davis. Huse recites some conversations word for word, displayed on a canvas of extraneous details including closing doors and window shades, ordering lunch, tipping of hats, noting facial expressions and remembering precise train departure times.

Why would Huse feign forgetfulness regarding the details of his most important conversation with Davis—one that resulted in the Confederate president assigning him to purchase military goods for the Confederacy? An assignment that required a monumental effort on Huse’s part and which would consume seven years of his life.

Was Huse’s deletion of such information deliberate?

This investigation attempts to answer these questions and shine a light on Huse’s overlooked activities and Confederate contributions.

The question of Southern conversion

Huse left no record of why he embraced Southern secession. By his own record of accomplishments, his Southern loyalty can be only assumed.

Validation of Huse’s Southern conversion is presented by John Massey, the first quartermaster of the Alabama Cadet Corps. Massey had known Huse prior to the war. In his 1916 Reminiscences, Massey writes of “Colonel Caleb Huse”: “But Huse was moved only by the highest principles in everything that he did. He thought that the South was right in its contention, and he placed his sword at the disposal of President Davis.”

But Massey’s assertion does not address why Huse thought the “South was right.” No other explanation for Huse’s conversion has been discovered.

Contemporary accounts are speculative.

In 1953, James B. Sellers published Volume 1 of the History of the University of Alabama. Huse is presented as the first commandant of the Alabama Cadet Corps (ACC). Huse accepted this position during the summer of 1860 and moved his family to Tuscaloosa. Sellers opined that Huse “may have come to the University of Alabama with Southern sympathies.”

Sellers presents two competing explanations for Huse’s presence in the state, both related to the ACC’s formation. One, by University of Alabama President Dr. Landon Garland, who was integral in creating the ACC, notes that the founding of the organization was for “the preparation of Alabama youth for war.” The other, by Huse in his memoir, explains, “The introduction of military drill and discipline…had no connection…with any secession movement in Alabama, and the fact a Massachusetts born man and of Puritan descent was selected to inaugurate the system will, or ought to be, accepted as confirmatory of this assertion.” Authors and researchers have ostensibly focused only Garland’s explanation of Huse’s Confederate allegiance.

Sellers’ presentation notwithstanding, the three most quoted reasons for Huse’s conversion are marriage to a Southern wife, interaction with the Southern social elite, and service under the command of Robert E. Lee. Each reason is worthy of examination.

His marriage: Harriett Pinckney Huse was born in New York. Her ancestry, the paternal Pinckney’s and maternal Marvins, were comprised of generations of New Yorkers.

Her characterization as Southern is connected to her uncle, William Marvin. In 1835, President Andrew Jackson appointed him U.S. District Attorney in southern Florida at Key West. He went on to become a federal judge and the provisional governor of Florida after the Civil War. Through some association with her uncle, Harriett spent part of her childhood in Florida. She apparently met and married Huse in Key West following his graduation from West Point.

To designate Harriett as Southern is inaccurate. She was a New York northerner. Any geopolitical interests she may have had remain undiscovered. Regardless, Harriett’s first duty was to her husband and 13 children. She managed the household through thick and thin while Huse pursued his career. This involved long separations from him and a number of arduous, long distance journeys.

To illustrate the point, when Huse accepted the appointment from Davis, he immediately moved to Europe. Harriett remained in Tuscaloosa with their children, one of whom had recently died. According to Confederate payroll records, Huse received funds paid directly to Harriett for approximately three months, at which time Harriett and children traveled by themselves to Europe (probably Paris) where they reunited with Huse.

Other actions by Harriett appear to support the path forged by her husband. She attended the christening of the Alabama and may have even participated in the event. The Harriett Pinckney, perhaps the only Confederate-purchased blockade runner, was named in her honor.

All things considered it is improbable that she influenced her husband to join the Confederacy. However, she definitely supported him in the pursuit of his career.

Interactions with Southern social elites: The explanation that the Southern social elite influenced Huse to join their ranks is subject to scrutiny. Prior to 1860, Huse appears to have never traveled south of the Mason-Dixon Line apart from his post-graduation assignment to Key West. When he arrived in Tuscaloosa as the commandant of the ACC, the mothers of a number of cadets known to be troublemakers threatened him with mutiny. These women did not want a Yankee overseeing the education of their sons. Sellers noted that the cadets approached Dr. Garland and informed him they “were prepared to run the Yankee out of the state.” Huse persevered, instilled needed discipline, and impressed everyone by the transformation of the ACC.

Factoring in the political climate of this time, namely the run-up and fallout of the 1860 presidential election, it is difficult to fathom a different acceptance of Huse by the Southern social elites versus that expressed by some of the ACC cadets and their mothers. Tuscaloosa could not have been a socially inviting environment to someone from Massachusetts, especially when that individual was more on record as to being loyal to his Puritan roots versus his never having written a confirmation of his conversion to southern politics and interests.

Robert E. Lee: The explanation that Lee influenced Huse is perhaps founded on Sellers’ speculation that Huse arrived in Alabama with southern sympathies. Huse’s professorship at West Point overlapped Lee’s position as Superintendent (from 1852 to 1855). There appears to be no surviving record of a continuing relationship between Lee and Huse after Lee left West Point.

There is little documented correspondence that links Lee and Huse. One letter written by Lee on May 11, 1853, to Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte, the brother to the former French Emperor is the exception. Bonaparte’s son had graduated from West Point in 1852 and like Huse, remained at the USMA as an assistant professor. Lee’s letter to the senior Bonaparte communicated his interest in the younger Bonaparte’s career. The letter includes one offhand mention of Huse: “Lt Huse went to W- [Washington] last Friday to see if he could accomplish a transfer to the ordnance.”

If Huse had fallen under Superintendent Lee’s sphere of influence, why would he seek a transfer that would end in his leaving the faculty led by his mentor? A review of the transfer request, sent to Secretary of War (Jefferson Davis, who ironically denied Huse’s transfer) on May 9, 1853, states that an assignment to ordnance “would afford me an opportunity of performing duties more congenial to my taste.” Huse’s interest counters the concept that he nurtured Southern sympathies at West Point in the early 1850’s under Lee’s influence.

A stronger case for Huse’s conversion can be made by the influence of Georgia’s William J. Hardee, who served as West Point commandant of cadets from 1856 to 1860. In 1859, after Huse received orders to leave West Point and return to the 1st U.S. Artillery, Hardee wrote a letter to the State Seminary of Learning of Louisiana, (predecessor to the Louisiana State University) recommending Huse to be the superintendent of their fledgling military academy. Lee never made such overtures on Huse’s behalf.

Huse followed up with State Seminary Board member Mason Graham in a letter dated July 20, 1859. His text was largely financially focused—he wanted to know how much he would be paid. About a month later, Hardee informed Huse that he had not been selected for the position. Huse followed up with a second letter to Graham seeking the return of all of the testimonials submitted on his behalf. The tone of Huse’s letter has a ring of sour grapes.

Ultimately a non-event in Huse’s career, it was probably driven more by an interest to remain in an academy environment rather than return to his artillery unit. Accordingly, Hardee was not attempting to influence Huse as much as he was attempting to facilitate Huse’s interests. In this regard there is no evidence of a Southern focus on anyone’s part, perhaps reinforced by the State Seminary’s superintendent selection: William Tecumseh Sherman.

Slavery and abolition: Historians and authors do not associate Huse with the issue of slavery, which would seem important respective to his Southern conversion narrative. Where did he stand on this issue? A late war (1864) New York Times article illuminates Huse’s position. The author was knowledgeable of Huse, and wrote, “Notwithstanding that while at West Point he (Huse) repeatedly expressed himself as opposed to slavery, yet, to the astonishment of his friends conversant with his opinions and his antecedents, early in 1861 his name held a prominent place in a petition from certain citizens of Alabama, to the Provisional Government at Montgomery, to take steps to reopen the slave trade.” This single quote presents the conundrum related to understanding Caleb Huse. Converting from a pro-abolition position to one of not just supporting slavery but advocating for the legal resumption of the transport of slaves across the Atlantic, is truly remarkable. Was Huse, while in Alabama, simply engaging political expediency to ingratiate himself to the Southern elite he was living among and being interactive with? If so, why?

Huse’s supposed Southern conversion is problematic. A better explanation is wanting.

Family connections to a powerful arms manufacturer

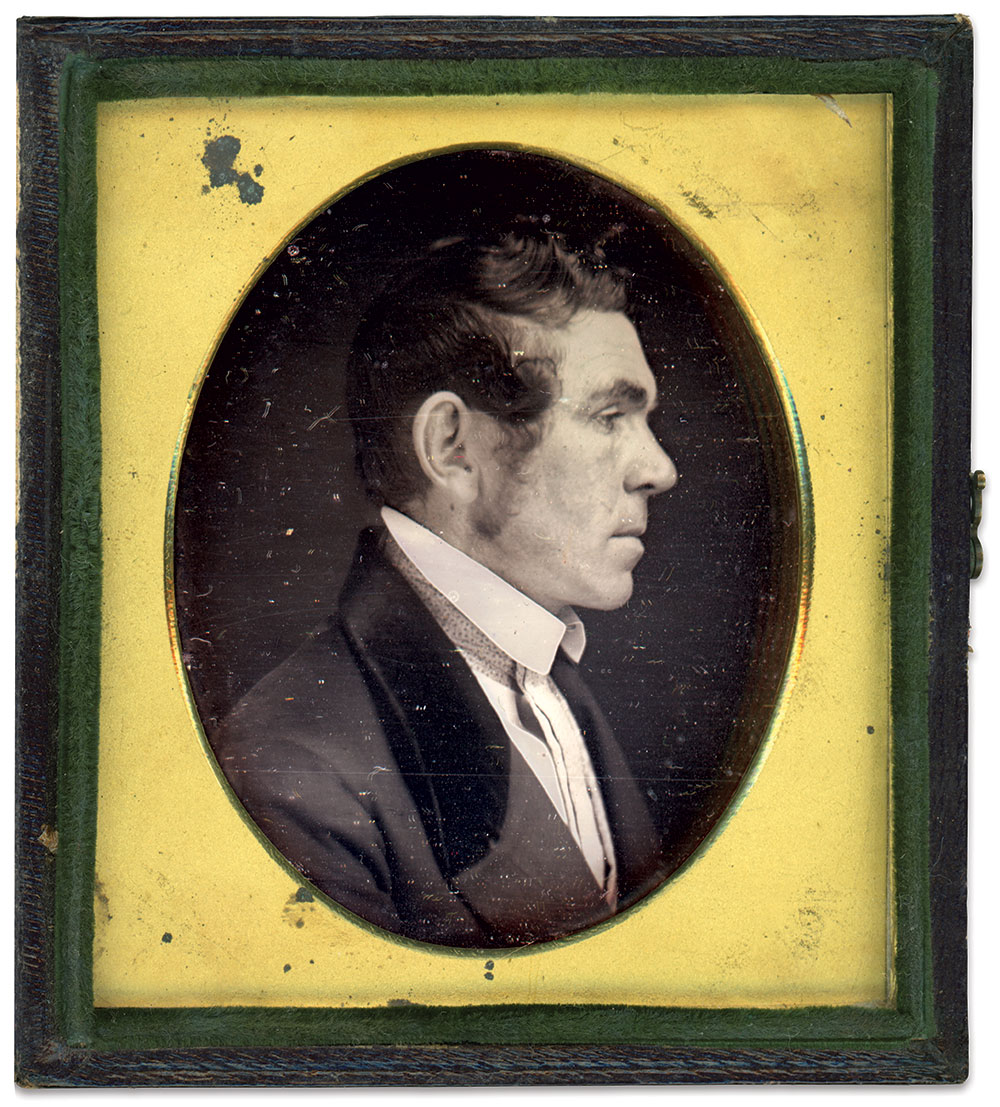

The better explanation may be found in Huse’s family connections to a global arms company. It is described in a 1935 family genealogy by Huse’s fourth son, Harry McLaren Pinckney Huse. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1878, received the Medal of Honor in 1914, and advanced to vice-admiral.

The genealogy notes that the Huse family began its American experience in Massachusetts in 1635. Huse’s grandfather, Samuel Huse Jr., owned and operated a foundry in Newburyport. It manufactured brass hilts for the early production of the Model 1832 artillery sword. The N.P. Ames Company in Springfield, Mass., produced these swords, and early examples display the N.P. Ames/Springfield mark on the blades and the S. Huse/Newburyport mark on the guard.

Like the Huses, the Ames family originated in England and arrived in Massachusetts in the mid 1600s. How Nathan Peabody Ames, Jr., and his younger brother James Tyler Ames came to be associated with Newburyport may have been entirely due to an association with the Huse foundry. The Ames brothers visited there often and married local women. One of these women was Samuel Huse, Jr.’s daughter Eleanor, known as Ellen. She married James Ames. Thereby, Caleb Huse, the son of Ellen’s brother, became the nephew of the younger Ames brother.

Historians have largely overlooked the relationship between Caleb Huse and Ames—a remarkable occurrence as the interactions of nephew and uncle proved instrumental in Huse’s career.

When Huse requested a transfer to ordnance in 1853, it appears he was working toward a position to interact with his uncle’s firm, the Ames Manufacturing Company. As noted earlier, that transfer request was denied. Huse made another attempt in 1859. In a September 13 request to the War Department for a six-month leave to go to Europe on behalf of Ames, Huse stated, “If I am not permitted to avail myself of the opportunity that now offers, it is probable that I shall never be able to go to Europe or any other foreign country. I am offered to have my expenses paid, and the business I wish to go on—for it is only business that calls me at the present time—is of importance to myself.”

The nature of the request—tending to family business—casts even more doubt on the Southern conversion theory.

The request reached President James Buchanan, who added his support, and the War Department granted it.

The business interest entrusted to Huse involved a promotional program to introduce the James rifling system to Europe. Charles T. James, the patentee, partnered with Ames to manufacture the cannon. Ames paid expenses for three men to tour Europe with a James’ 12-pound rifled cannon: Huse, James’ son-in-law John S. Slocum, who became colonel of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry and died in the First Battle of Bull Run, and Lt. John W. Todd, West Point 1852.

Though the Americans were unsuccessful in Europe, Huse benefitted in four important ways:

- Reuniting with former West Point faculty member Jerome Bonaparte II. Bonaparte left the U.S. military in 1854 to offer his services to French Emperor Napoleon III, a relative. Jerome provided Huse with access to the Emperor to present the James artillery technology. According to a letter from Huse to Slocum in late December 1859, Jerome presented much information to Huse on the capability of European artillery as he witnessed it during the Crimean War. After the Civil War began and Huse returned to Europe as a Confederate agent, Jerome may have facilitated accommodations in Paris for him and his family. Six of the 13 Huse children were born in France during the war and early postwar years.

- Meeting James Henry Burton. A close associate of James T. Ames, who had employed the Virginian in Chicopee and nominated him to install and operate Ames’ machinery for the production of Enfield rifle-muskets at the Royal Small Arms Factory in England, Burton modified the design of the minié ball before the war. A prewar letter from Burton to Ames confirms that Burton interacted with Huse during his time in England.

- Observing the London Armoury Company facilities in England. Huse witnessed the manufacturing of Enfield rifles produced by machinery made and delivered by James T. Ames in 1858.

- Networking. The contacts made with English and European military establishments significantly assisted his procurement efforts on behalf of the Confederacy.

Huse returned from Europe and reunited with his family in May 1860. With the clock ticking on his leave of absence from the army, and seeking new opportunities, he had arrived at a turning point in his career. Writing to Ames from Owego, N.Y., on May 31, he described his struggles to sort out receipts and made apologies for not being able to pay a $200 deficit. Huse added, “I am living in a pleasant and cheap place and spend my time in gardening, amusing the children, and seeking for some plan by which I can retire from the Army. I must say my hopes of being able to do so diminish, rather than increase.”

When his leave of absence expired, the military expected Huse to return to his artillery assignment, still in Key West. His May 31 letter reveals his openness to other options and apparently fishing for his uncle’s help. One promising opportunity involved an appointment to a proposed U.S. military board to study rifled cannon. Huse informed Ames that he had already contacted Capt. William Maynadier, assistant to the Chief of Ordnance, with a request to join the board. Huse’s letter implies that Ames utilized his connections in Ordnance to facilitate Huse’s transfer to that department. Huse, in fact, would be nominated to the board in July. The board completed its work by the end of the year, and it resulted in a large contract to Charles James and the Ames Manufacturing Company.

Also in play was an invitation from the University of Alabama to join the ACC. Huse claims in his memoir that it awaited him on his return from Europe, but he did not mention the ACC option in his letter to Ames. It is more likely that he received the ACC offer nearer to July and coincidental to the ordnance board nomination.

Remarkably, Huse declined the board position and returned to an academy position in Alabama.

Alabama academy and commercial agent

Having spent nearly 13 years at West Point, including four as a cadet, Huse certainly had experience in the military training of young men. His acceptance of the appointment to oversee a new academy in Alabama seemingly preempted any desire he had for at least seven years for a transfer to the Ordnance Department.

But did it?

A letter to the editor published in the New York Times on April 10, 1864, (the same as referenced in the Slavery and abolition section above) titled “A Rebel Diplomatist—Sketch of Capt. Caleb Huse” offers a different perspective. The anonymous author, “An Army Officer,” stated that Huse purchased military equipment for the ACC and “was industriously engaged during the Winter of 1860-61 in organizing and preparing his new charge for the part it was soon to perform in the rebellion.”

Huse no doubt considered equipping the ACC a first order of business. However, the Times letter claims that Huse purchased the listed items. How did he do that? Concurrent to the University of Alabama’s preparations to create the ACC, Alabama expanded its militia through a legislative act when it created the Alabama Volunteer Corps (AVC) in February 1860. Governor Andrew B. Moore reported in an 1860-61 legislative session that 9,562 muskets, rifles, carbines, pistols and sabers had been purchased for the AVC from Ames.

In March 1860, a month after Alabama created the AVC, Ames purchased 1,000 conversion muskets from the New York Arsenal, likely in order to fill orders to arm the AVC. The timing indicates Ames’ involvement and knowledge of Alabama’s military plans when Huse received the unsolicited ACC appointment. This circumstantial evidence supports an explanation of why Huse passed on the ordnance board appointment in favor of the ACC. Huse would engage a dual role as commandant of the ACC and an agent for Ames. Huse would have benefitted financially under this arrangement, collecting his salary from the University while earning commissions from Ames on the sale of military goods.

As this plan may have unfolded, Ames could have organized the military equipment for the ACC and on an assumption or understanding of payment based on previous transactions with the AVC. The historic record confirms that Huse interacted with the Alabama legislators and Gov. Moore to appropriate funds for the ACC. The specific disbursement of these funds, and evidence of Huse’s facilitation of military purchases for the AVC, has not yet been discovered.

Huse’s interaction with the state of Alabama, and his possible role as an Ames agent, would have occurred for approximately six months prior to the meeting with Davis. As such, Huse would have successfully infiltrated the state’s administration. Prior to the war, with the Alabama and Confederate governments both located in Montgomery, it is plausible that knowledge of Huse’s unique affiliation to a Northern arms manufacturer eventually came to Davis’s attention.

Davis would have been very familiar with the Ames company, which had been contracting with the U.S. War Department since the 1830s. During Davis’ 1853-1857 stint as Secretary of War in the Buchanan administration, Ames provided gun manufacturing machinery to both the Harpers Ferry and Springfield Arsenals. Following the 1859 John Brown Raid, most if not all of the states that would secede began arming themselves. Evidence exists that Davis advised the governor of Mississippi as early as January 1860 that rifles could be obtained from James T. Ames. Davis noted Ames’ ability to deliver arms within a certain number of weeks, indicating that Davis had either been in direct communication with Ames, or through agents.

Davis might also have been aware of actions by Virginia in 1860 that directly connect Ames to the state’s military aims. They are detailed in a 70-page document recording the proceedings of Virginia’s Board of Commissioners to fulfill “An Act making an appropriation for the purchase and manufacture of Arms and Munitions of War.”

Virginia desired the capability to manufacture weapons—rifled muskets specifically. James T. Ames engaged in the machinery bidding process from about March to August. The Commissioners and Gov. John Letcher visited the Ames factory in Chicopee on May 3, and met with Ames in Springfield at 8 p.m. the same day. The record notes, “a full enquiry was Entered into, concerning all the essential points connected with the organization of the Armory at Richmond…In the course of this conference the question was submitted to Mr. Ames, whether he would be willing to take the Armory property, put up the requisite machinery for rifle muskets, & Supply the State with a definite amount, say; 5000 Muskets per annum, the whole establishment to revert to the State at the End of a given term of years.”

On this day the Virginians learned about Ames’ business activities in England. Ames had delivered gun manufacturing machinery to both the government controlled Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock and the privately held London Armoury Company (LAC). The deal with LAC, estimated at $1 million in 1860, may have been furnished similarly to that proposed by Letcher and the Virginia Commissioners. In fact, details of the LAC commercial contract, expressed by Ames, may have inspired the Virginian’s proposal.

It is unknown if their 70-page record found its way to Davis in Montgomery.

Huse returns to Europe—as a Confederate agent

In his memoir, Huse’s travelogue from Tuscaloosa to Portland, Maine, reads like a spy novel. He presents his movements as an attempt to avoid being captured as Confederate agent. That’s curious as he had just been given this secret position. How would anyone had known Huse’s role outside of Alabama?

Huse details his travels from Montgomery to Charleston, S.C., to New York City to collect $500 in gold from the Trenholm Brothers, part of the empire of financier George Trenholm.

Seemingly, it would have been far easier to receive funds directly from Trenholm’s home office in Charleston. Moreover, why did Huse elect to carry gold instead of a safer credit line? Likely, it was part of a larger piece of fiction. In reality, Huse probably repeated the same arrangements he had made for his first European trip for Ames by arranging credit through New York City’s Brown Brothers & Co.

Huse’s travelogue from Alabama to Europe is the stuff of spy novels.

Brigadier General Richard Delafield, who served as West Point Superintendent while Huse served as a professor, reported spotting him in New York City on or about May 1, 1861.

Huse notes he received the gold in New York City, then continued to Buffalo and Hamilton, Ontario. He planned to catch a vessel at Montreal and cross the Atlantic. But determining he would be delayed, he reversed course to Portland, from where he departed.

The Canadian leg of the trip is probably another fiction. It is likely he traveled from New York City to Chicopee, and then Portland. Evidence for a Chicopee stop is inferred from two late 19th century biographies of Emerson Gaylord. He had purchased Ames’ leather works in 1856 and operated the manufactory on the Ames factory grounds in Chicopee.

One Gaylord biography published in the 1879 History of the Connecticut Valley states: “On the day Fort Sumter fell, Mr. Gaylord had a stock of accouterments for the South on hand… Before night of the same day a noted speculator from New York arrived and offered Mr. Gaylord five thousand dollars more than he would otherwise receive.” Another Gaylord biography in the 1897 New England States recounts, “On the very day that Fort Sumter was fired upon Mr. Gaylord had on hand a large stock of accouterments [ten thousand sets are noted]…prepared for the South, which…were finally furnished to the United States…Just before shipping these goods he was approached by a rebel speculator from the South offering him…$6 a set…a difference on the total number of $10,000.”

Huse was likely the speculator. Though it would have been impossible for him to be in Chicopee the day Fort Sumter fell, he could have arrived before the accouterments were shipped. Other considerations that favor Huse include his knowledge that Chicopee was a warehouse of military goods and Davis’ intent on procuring items to support the Confederate army. It is easy to imagine Davis encouraging Huse to visit Chicopee on his way to Europe. It is also easy to understand Ames’ reluctance to attempt shipments to the South after the war had commenced.

In his memoir, Huse makes only a single reference to the Ames Manufacturing Company. It is associated with the LAC’s purchase of gun machinery. Huse comments that when he arrived in London in 1861, he determined “to secure the London Armory as a Confederate States arms factory.” He adds, “I succeeded in closing a contract under which I was to have all the arms the Company could manufacture…This Company, during the remainder of the war, turned all its output of arms over to me for the Confederate army.”

Huse’s claim is questionable. According to modern weapons authorities, surviving purchase records show limited numbers of LAC-sourced Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles delivered to the Confederacy, and that these weapons are rarities in U.S. collections. This evidence indicates Huse exaggerated his control of the LAC production. But did he? Huse may have traded the highly machined LAC produced Enfield rifles for lesser weapons. Such transactions could be hidden from the Confederacy and would have resulted in significant commissions for Huse and everyone associated in the scheme.

A wartime letter indicates Huse’s influence with the LAC operation and ownership. On June 12, 1863, he wrote from Paris to Col. Josiah Gorgas, the Confederate Chief of Ordnance, “I have already obtained from the manufacturers…full estimates of the cost of machinery Mr. Burton has in view…I have also an offer of sale from the London Armory Company of their entire plant…The advantage of…this purchase would be that it would save several months of delay.”

The reference to Burton is noteworthy, for Huse knew him well. James Burton became associated with Ames when employed at the Springfield Arsenal. In the late 1850s, Burton joined Enfield Lock, where he oversaw the installation and operation of Ames-made machinery. Though employed by the British firm, evidence indicates he continued to represent Ames’ interests, much as Huse did. Burton left England when the war started and supported the Confederacy and its weapon manufacturing concerns. Burton proposed the establishment of an arsenal in Macon, Ga., for which Huse was attempting to source machinery, but that factory never came to be built.

We may never know what Huse presented to Davis during their 1861 meeting regarding the Ames affiliated gun manufacturing operations in England.

In the June 12, 1863 letter, the manufacturers to which Huse refers most likely included Ames. More to the point of his meeting with Davis in early 1861, Huse probably knew he would have discretion respective to the Enfield production at the LAC. Huse’s influence would eventually manifest to the point of being able to box up the whole LAC operation up and ship it to Georgia–seemingly, better effected if Ames had retained ownership of the machinery. We may never know what Huse presented to Davis during their 1861 meeting regarding the Ames affiliated gun manufacturing operations in England. However, as Huse was fully informed as to their organization and ownership, Davis would have had to be impressed with what Huse could deliver.

Huse continued to negotiate Confederate contracts from European makers through the rest of the war. When it ended, Huse found himself stranded in France. He continued as a freelance agent in the European arms trade. In December 1868, President Andrew Johnson pardoned anyone involved in insurrection against the United States from a charge of treason. Huse and his family returned home.

Epilogue

In 1889, Jefferson Davis wrote to Huse. Davis, bedridden with only months to live, had been accused of negligence in having selected Huse for the mission to Europe.

Huse replied on July 19 from his home in Highland Falls, N.Y. He acknowledged this as the first time they had been in contact since Appomattox. He inferred that he performed the assignment well but provided no insights or details about his support of the Confederacy or their meeting in 1861.

Huse made two remarkable comments in his letter to Davis.

First, he stated, “I lent all the official letters received by me during the war to a gentleman in Paris…and I have never seen them since.” These could be illuminating documents, if they still exist. One wonders if Jerome Bonaparte was the recipient of Huse’s war time communications. Bonaparte eventually returned to the U.S. and married into the powerful Appleton family of Massachusetts. From the mid-1840s through the course of the war, the Appleton’s were major shareholders of the Ames company.

Second, “I came back to this country as soon as I learned it would be safe. I had literally nothing but a little borrowed money when I landed…I have hardly bettered my condition since.” This is a curious statement. The 1875 U.S. Census reports Huse living in a framed house valued at $5000. By 1879, Huse had established the Highland Falls Academy, a West Point preparatory school, at a location referred to as “The Rocks.” Photos of the well-appointed building suggest that Huse had incurred serious debt or hid the wealth.

If Huse had only been a Confederate agent during the war, the poor financial condition he described, and perpetuated by authors since, would likely fit. However, as an agent for Ames, dealing in large volumes of military machinery and weapons on behalf of the Confederacy, the resulting commissions would have added a considerable sum to his bottom line.

It is important to reiterate that this narrative presents the Huse—Ames relationship as an explanation for Huse’s career decisions prior to the Civil War. The evidence is largely circumstantial. Irrefutable evidence is lacking, but period obfuscation of Huse’s speculated activity as fact is understandable in light of Ames’ importance as an arms manufacturer for the U.S. War Department. Association with any effort to support the Confederacy would have been viewed as treason if discovered. What is more intriguing though is whether certain individuals of the federal government were aware of what Huse was up to, and were not opposed to his activities.

What is the analysis of Caleb Huse if even half of this presentation is correct? It’s a complicated effort as, indeed, Huse was a complicated individual. The easiest judgment is to simply call him a traitor. However, that determination is reached on an assumption that the chess board is already in play—one side opposing another. In this kinetic, Huse was opportunistic and ostensibly, apolitical. While his career can be discussed and debated, none of it would have occurred had the pieces not been positioned on the board in the first place. In a larger sense of the American Civil War, who placed them there, and why?

Ron Maness is a MI Contributing Editor.

About This Investigation: Ron Maness has investigated the pre-war artifacts and activities of the Ames business in Chicopee, Mass., for approximately three decades. Through his research the theory has emerged that the stockholders of the Ames Manufacturing Company, and the Massachusetts Arms Company, facilitated the Civil War. For more information, see Ron’s profile of James T. Ames, “Agent of the Cotton War.”

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.