By Mark H. Dunkelman and Megan Kelley

Amos Humiston has been in the public eye since his death on the battlefield of Gettysburg. The discovery of his unidentified body with an ambrotype of his three children clutched in hand, and the campaign to identify him is the best-known photo-sleuthing story of the Civil War. It has been told time and again across the generations.

Each generation has had its guardian of the Humiston story. The physician who took it upon himself to identity the children; Aging veterans in the twilight of life; A reporter on the eve of America’s involvement in World War II; Curatorial staff of the original exhibit at the opening of the million-dollar Gettysburg Visitor Center in 1962.

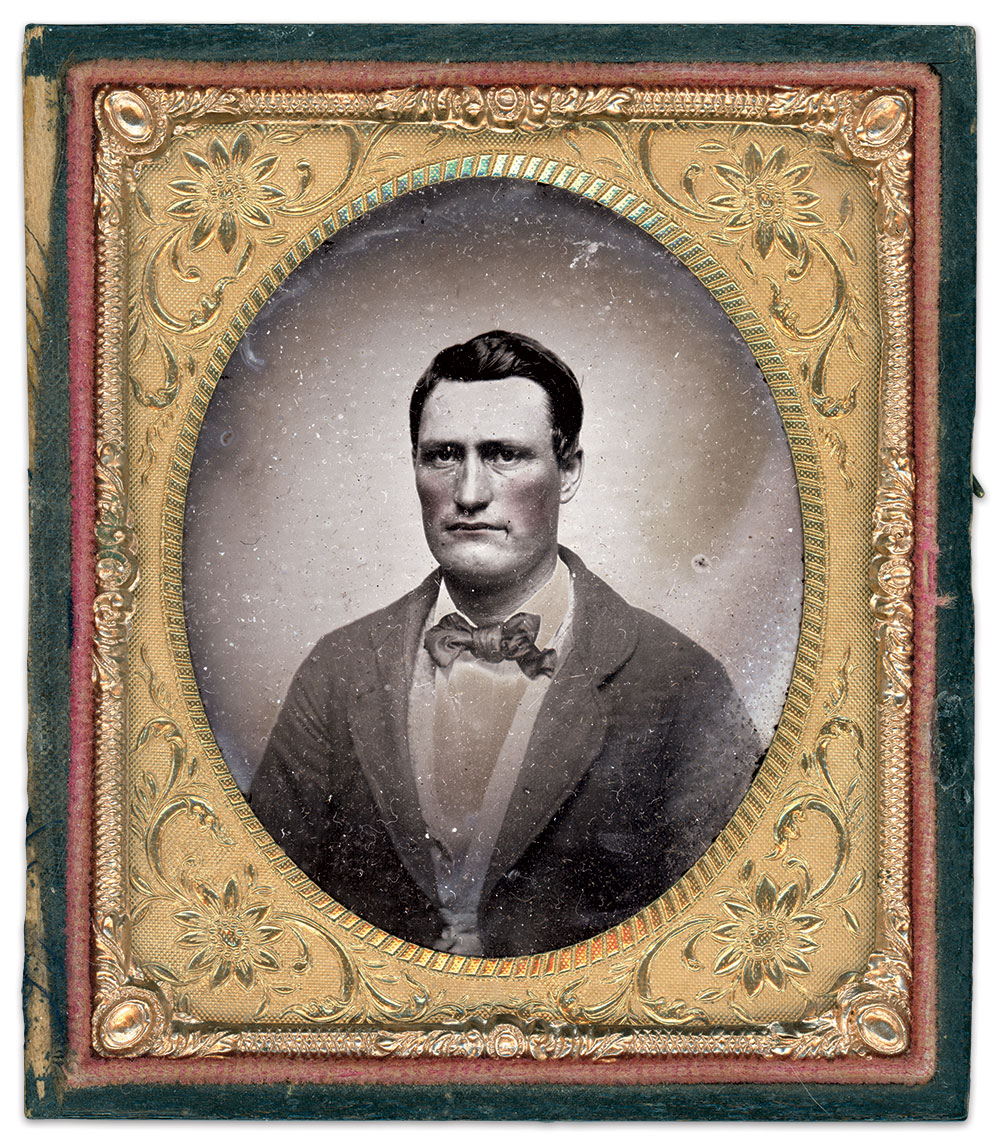

Two of today’s custodians, Mark H. Dunkelman and Megan Kelley, preserve the legacy of the Humiston story in this generation. Dunkelman has written and lectured extensively on the history of the 154th New York Infantry, Humiston’s regiment. He also created the mural at Coster Avenue in Gettysburg, which depicts Sgt. Humiston and the regiment in action during the Brickyard Fight on July 1, 1863. Kelley, a historian, descends from Humiston on her father’s side of the family. She is the current caretaker of this ambrotype of her great-great-grandfather. Though this portrait has been previously published, we see it here for the first time in color, at large size, and without the uniform painted over his civilian clothes.

Mark and Megan share their observations about this image.

—Ronald S. Coddington

The Journey of a Father’s Portrait

By Mark H. Dunkelman

This sixth-plate ambrotype by an unidentified photographer is Amos Humiston’s only known portrait from life. It was taken sometime before July 1862, when he enlisted at Portville, N.Y. He left behind his wife and three children only after being assured that they would be cared for during his absence. His regiment, the 154th New York Volunteers, was badly bloodied in its first battle, at Chancellorsville. A week later, Amos wrote to his wife, Philinda. He reported escaping a close call during the fighting when a spent ball hit him in the chest. He added, “I got the likeness of the children and it pleased me more than anything that you could have sent me.” Two months later, at Gettysburg, the ambrotype of cherubic-faced Frank, Alice and Fred Humiston was found in their slain father’s hand. As Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper put it, the image had drawn “the last thought of a dying father.” It was also the single, sad clue as to his identity and that of his family—a mystery that was solved when a wave of publicity about the incident swept the North and the Humistons were identified.

The ambrotype of the Humiston children is not known to survive. But the image of the “Children of the Battle Field” is nevertheless familiar because of the many carte de visite copies that were made during and immediately after the Civil War, and the subsequent reproductions as illustrations in books and magazines. Humiston children cartes de visite are still readily found in the collector’s market, as Rick Leisenring and I described in “The Likeness and Legacy of the Children.” (Military Images, Summer 2020.)

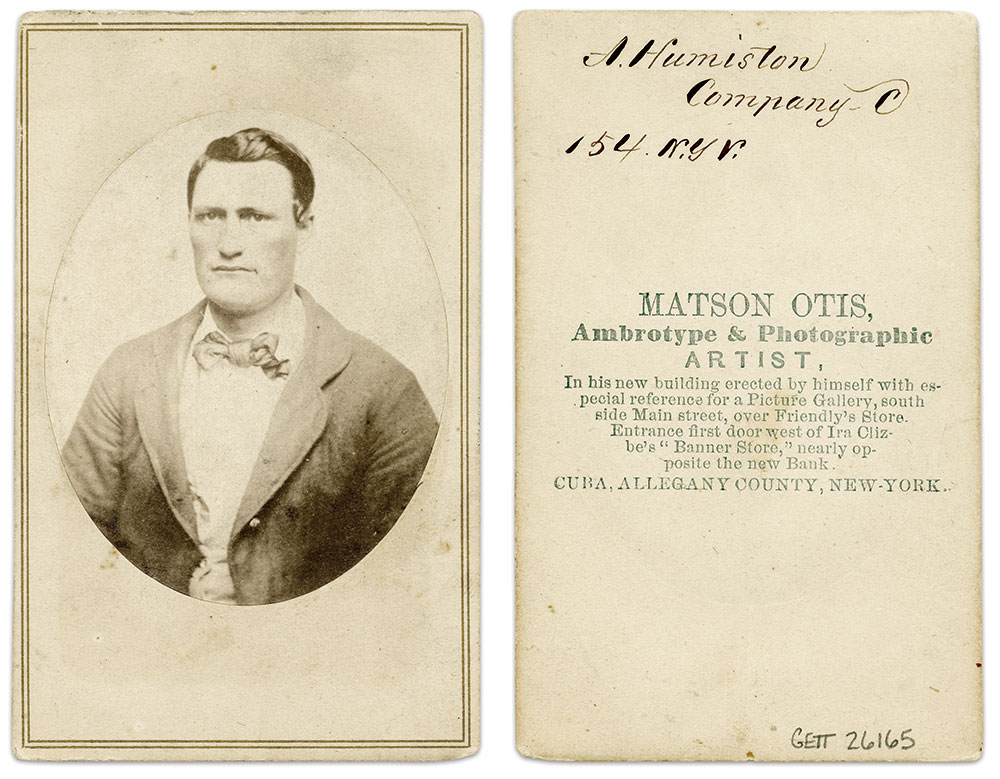

This ambrotype of Amos has been preserved by four generations of his descendants. It is reproduced here for the first time in high resolution and color, courtesy of Amos and Philinda’s great-great-granddaughter Megan Kelley. This is not, however, the first time it has been reproduced. While the war still raged, Philinda Humiston evidently had carte de visite copies of this image made by Mason Otis, a photographer in Cuba, N.Y. This perhaps was done at the request of New York State’s Bureau of Military Statistics. That agency loaned a framed display of the Otis carte of Amos paired with a large print of the children’s picture to the philanthropic Metropolitan Fair held in New York City in 1864. How many cartes of Amos that Otis produced is unknown. In 1958, Fred Humiston’s two daughters presented one to the Gettysburg Battlefield Diorama and Museum on Steinwehr Avenue. According to a letter to the editor in the July-August 1981 issue of Military Images, one was purchased at a flea market in 1981 by Les Turner of Wilmington, Mass. An example is currently on display in the museum at the Gettysburg Visitors Center.

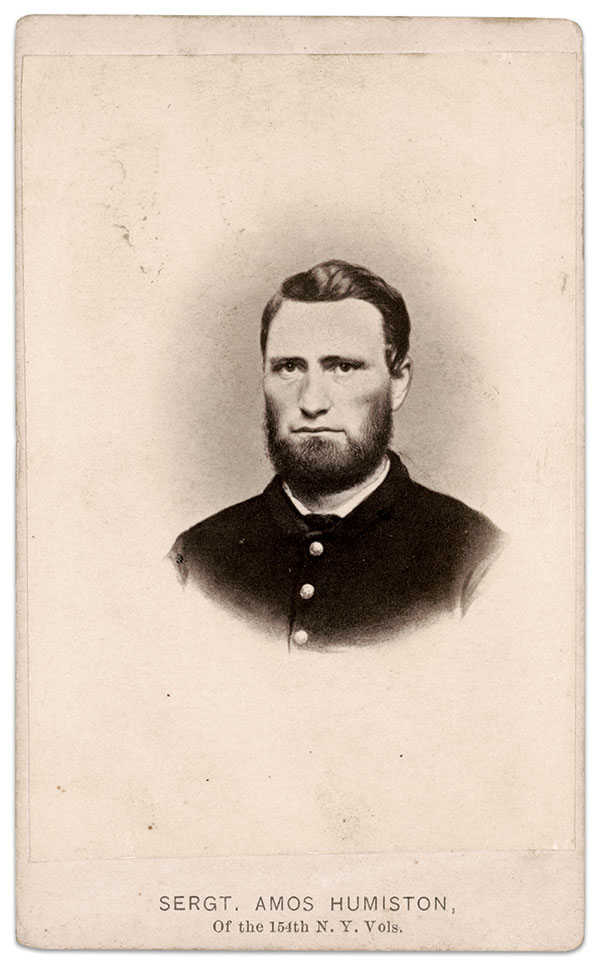

This ambrotype also served as the basis of a much more familiar image of Amos. After he was identified and his family became reluctant celebrities, there was a demand for a picture of the faithful father. Rather than issue a copy of the ambrotype as it was, as Mason Otis had done, it was decided to depict Amos as a soldier. Through the magic of retouching, an artist provided Amos with a beard and a uniform. The Philadelphia photographer Frederick Gutekunst appears to have had a monopoly on issuing the bust-view cartes de visite of the faux soldier. They included an inscription identifying Sgt. Humiston on the front and a summary of his story on the back. Like the cartes of the Humiston children, the cartes of Amos were sold to benefit the orphans and—in a later edition—the Homestead orphanage in Gettysburg, which Amos’s tragic death and heart-stirring devotion had inspired. The cartes de visite of Amos as a soldier are much rarer than those of his children. An example preserved by Megan Kelley has Gutekunst’s imprint but no other inscriptions. Was it a prototype sent to Philinda for her approval?

This ambrotype was brought to the public eye in 1993 when Megan and her late father, David Humiston Kelley, brought it to Gettysburg for the dedication of the Amos Humiston monument on the grounds of the fire station on North Stratton Street. On that occasion, I had the great pleasure of staying with the Humiston descendants at the former Homestead orphanage building turned guest house, and delivering the main address at the monument dedication ceremony. During that memorable weekend my wife, Annette, took black-and-white photos of the ambrotype and other Humiston family photographs that Dave and Megan had brought with them. Thanks to their kindness, Amos’s portrait appeared as the frontispiece and on the dust jacket of my 1999 biography, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier: The Life, Death, and Celebrity of Amos Humiston. From there it has spread widely. But here, thanks to Megan Kelley, we see it in crystal-clear color for the very first time.

A Roadtrip to Family History

By Megan Kelley

As a descendant of Amos Humiston (on my father’s side) and someone who grew up to be a historian, I’m honored that the story and ambrotype of Amos remains of historical interest. My dad loved genealogy and his knowledge about the family tree gave my siblings and me a vivid window into the generations that came before, and it is really in his memory that I write this brief recollection.

In June-July 1993, I acted as chauffeur in a long winding road trip with my father, heading eastward bound from Calgary with multiple destinations on the itinerary, including family haunts in Boston, upstate New York, and especially Jaffrey, N.H. But what turned out to be the most memorable stop was in Gettysburg, Pa.

On July 3, 1993, the Amos Humiston Memorial was unveiled in Gettysburg, a rock monument with a plaque depicting Amos with his three children, Frank, Frederick and Alice. To my knowledge, this was the first Civil War monument in honor of family left behind and this “unknown soldier’s” love for them. The monument was funded through donations with strong community support, which somehow made it an even more fitting tribute.

Growing up I had vaguely known that one of my great-great-grandfathers had died at the Battle of Gettysburg, but not the details. Arriving in Gettysburg that summer for the dedication ceremony, I finally heard the full story about Amos Humiston and the “Children of the Battlefield” and their place in Civil War history, a moving account I will never forget.

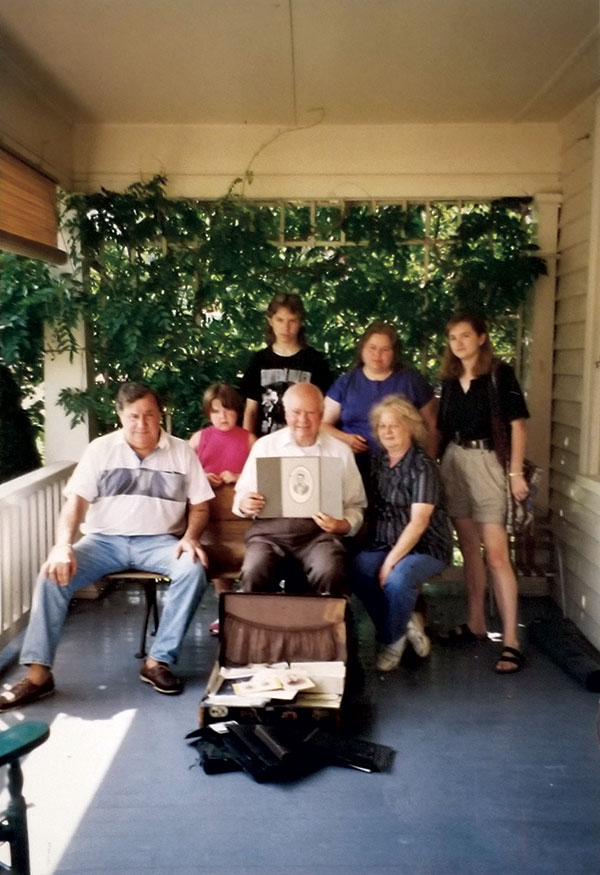

I was one of many descendants of Amos and his three children that came for the ceremony, a group that included my father, David Humiston Kelley, a grandson of Franklin G Humiston and Carrie Tarbell; Alan Cox, a grandson of Fred Humiston and Nettie Orne; and Alice Humiston, another great-granddaughter of Franklin, along with her mother Lillian Humiston and her children, Timothy and Clarissa. The event memorably included a reading by a Scottish poet, Steve Rady, who had been inspired to write a poem about Amos, “The Soldier,” and a rendition of “Children of the Battlefield” by the Portville singers, as well as an informative address by Mark Dunkelman, who literally wrote the book on Amos Humiston.

For the visit, we all stayed at the Homestead, at that time a bed-and-breakfast lodging, but historically the site of the orphanage run by Amos’ widow Philinda after the Civil War. This group photo of descendants of Amos Humiston was taken on the front porch in July 1993.

Truly, William Faulkner got it right: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.