By Ronald S. Coddington

General Joe Johnston’s headquarters buzzed with activity early in the morning of May 31, 1862. Staff aides and couriers dashed in and out of the Virginia countryside east of Richmond with orders and messages to senior commanders as they advanced their divisions into position to attack the enemy in the vicinity of Seven Pines.

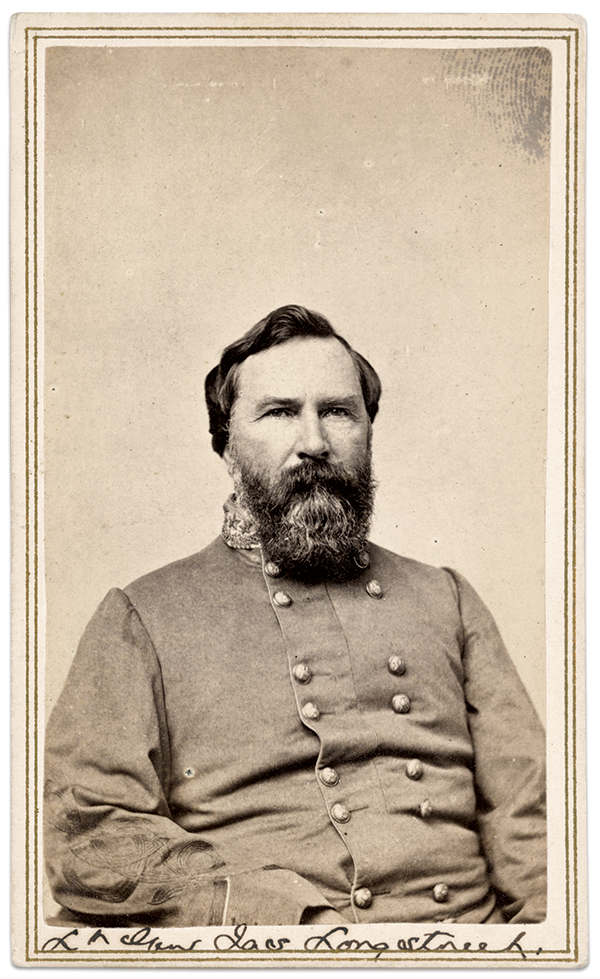

At one point, confusion arose as to the location of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s division. As conflicting messages filtered in, the quiet-mannered Johnston worked diligently to untangle the mess and get everyone back in motion. As precious minutes ticked by, fresh intelligence arrived that Longsteet’s division likely marched along the Williamsburg Road instead of the Nine Mile Road where Johnston expected it to be.

Johnston didn’t believe the report. Eager to hurry everyone up, he dispatched one of his staff aides, Lt. James Barroll Washington, with verbal orders to locate Longstreet and straighten out the line of march. James promptly saddled up on his horse and sped off at top speed down Nine Mile Road.

He did not return.

Baltimore, Beall-Air, and West Point

Lieutenant Washington’s journey began 23 years earlier and 150 miles north in Baltimore as the second of four children born into a prominent family. His father, Lewis William Washington, was a grandson of John Augustine Washington, the older half-brother of Gen. George Washington. James barely knew his mother, Mary Ann Barroll Washington, who died of a sudden illness when he was five years old. Her father, prosperous Baltimore merchant James Barroll, was young Washington’s namesake.

Called James, Jim, and Jimmy, he spent his formative years in Baltimore and the western Virginia manor Beall-Air, located about five miles west of Harpers Ferry. Father Lewis held between 11 and 12 enslaved men, women, and children on the manor grounds.

Heirlooms belonging to George Washington were displayed in a case inside the stately residence. They included pistols presented to him by Lafayette, and a favorite steel-hilted sword believed to have come into his possession during the Revolution. It is easy to imagine little James taking an interest in these historic artifacts.

How much time James spent at Beall-Air during his youth is unclear. Evidence suggests part-time as he attended private schools in Baltimore and Alexandria, Va. His education at an Alexandria boarding school is noteworthy. Run by respected educator Benjamin Hallowell, the school attracted elite students preparing for higher education. They included Robert E. Lee, who studied mathematics with Hallowell for a month before entering West Point.

James, like Lee, was destined to attend the U.S. Military Academy. Nominated by his father to fill an at-large slot, James entered West Point in June 1859. His arrival left a lasting impression on fellow cadet Morris Schaff. “We had a Washington directly from the Washington family of Virginia,” he boasted in his 1907 memoir, The Spirit of Old West Point. Schaff went on to list other sons of prominent statesmen, upper crust families of generational wealth, and captains of early industry.

Schaff added a caveat for those who might suspect such high-born boys received special attention: “They stood on exactly the same level as the humblest born; and, had any cadet shown the least acknowledgment of their social superiority, he would have met the scorn of the entire battalion. It was a pure, self-respecting democracy.”

Though Schaff did not offer examples of the “humblest born,” cadet George Armstrong Custer might have been on the list. The son of a blacksmith and farmer in Ohio, Custer could fairly claim he hailed from industrious, independent ancestors in the Orkney Islands off the northeastern coast of Scotland.

Custer had entered the Academy two years before James, and he left a lasting impression. “The rarest man I knew at West Point was Custer,” James wrote after the war. “The first time I saw him he was about twenty years of age and had just returned from furlough. All of us plebes were standing back, unnoticed and uncared for, in subdued admiration of the happy fellows receiving such hearty greetings from the grey coated crowd encircling them when a hundred throats went out in various forms of ejaculation, ‘Here comes Custer!’”

James was not impressed with that first glimpse. “Looking beyond the crowd I saw a cadet in furlough uniform approaching from the guard tent. I failed to note anything in his appearance that warranted the attention he received. I saw only an underdeveloped looking youth with a poor figure, slightly rounded shoulders and an ungainly walk. But this was Custer then considered an indifferent soldier, a poor student and a perfect incorrigible.”

Cadets rally around James after John Brown’s Raid becomes personal

On a September day in 1859, as Cadet Washington adjusted to his plebe year, his father, Lewis, walked along a Harpers Ferry street when a stranger approached him. The man inquired about George Washington’s relics and asked if he might visit and see them. Lewis, well known about town and assuming the individual to be an armorer on business, agreed.

The stranger showed up at Beall-Air soon afterwards. Lewis discovered they had a mutual interest in guns. They went so far as to put up a target and fire two revolvers carried by the individual, who revealed he used them as a buffalo hunter in Kansas.

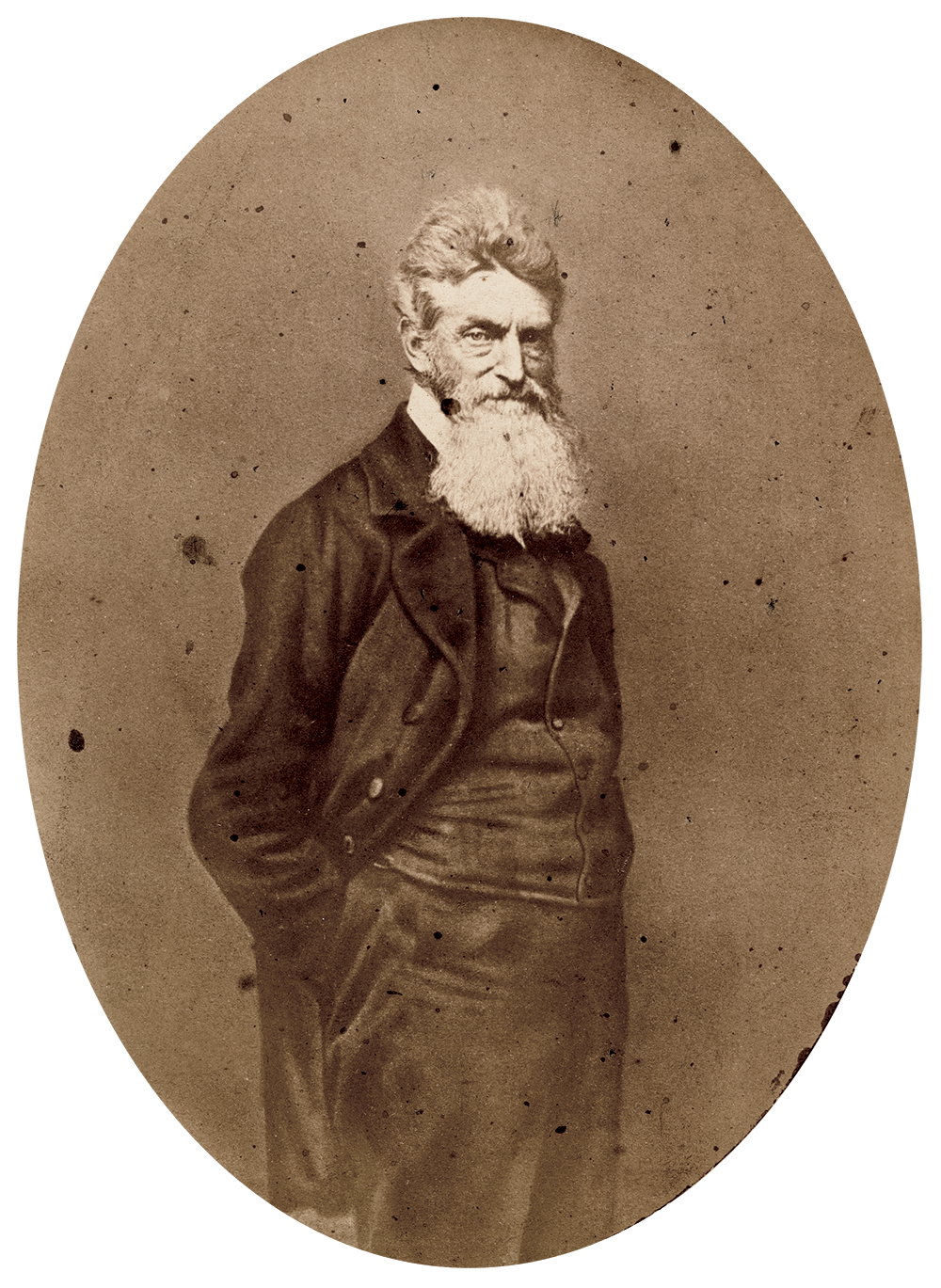

The mystery person, John Edwin Cook, was on secret mission. He scouted Beall-Air and other area properties for abolitionist John Brown in the lead-up to his raid on Harpers Ferry. If all went successful, Brown and his volunteers would spark a revolt and ignite a full-scale insurrection against the federal government to end slavery.

Beall-Air and Lewis could be useful to their plans, Cook concluded.

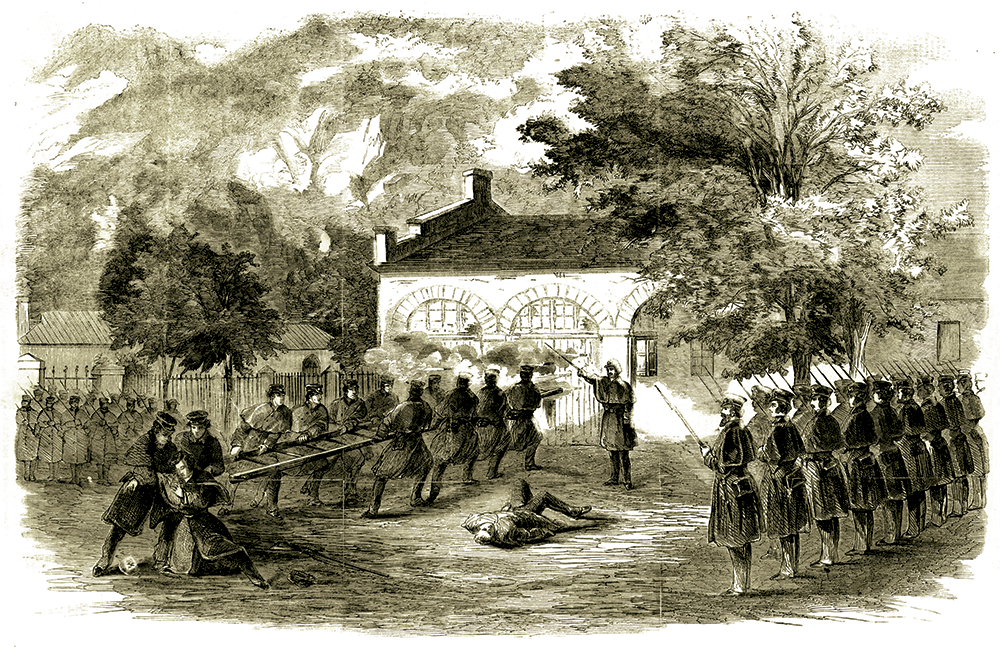

A month later, on October 16, Brown and his raiders seized the Harpers Ferry arsenal with little resistance. Cook led a six-man detachment to Beall-Air after midnight and took Lewis hostage. The raiders confiscated George Washington’s sword and one of the pistols, the family carriage and wagon, and three enslaved men. They carried them all, with Lewis, to the engine house on the arsenal grounds, stopping along the way at another residence to take more hostages.

Back at West Point, news of the insurrection captivated the cadets. They rallied around James after they learned about his father’s precarious situation. “The feeling was very great,” recounted Cadet Schaff.

Meanwhile, local Virginia militia poured into Harpers Ferry, and a contingent of about 90 U.S. Marines commanded by Col. Robert E. Lee followed on its heels. Brown, surrounded and outnumbered, set about negotiating a way out. But the Marines ended the insurrection on the morning of October 18. Colonel Lee ordered an attacking party to enter the engine house. As they approached the door, Brown, armed with Washington’s sword, laid the relic upon a fire engine. On the signal of Lt. J.E.B. Stuart, the Marines crashed through the door. Amidst the rush of men, fire of muskets and sword slashing. Brown and his raiders were captured.

An alert Lewis grabbed Washington’s sword and eventually recovered most of his possessions, with the exception of the pistol.

The sword used by Brown in an insurrection against the government which Washington served as its first president is symbolic of the underlying cultural and political tensions that tore at the fabric of the country.

Brown went to the gallows after being tried and found guilty of treason against the state of Virginia. His co-conspirators, including Cook, suffered the same fate.

From Cadet to Confederate

John Brown’s Raid deepened the fissures of disunion among the states. In less than a year, the presidential election of 1860 elevated Abraham Lincoln to the nation’s highest office, exacerbating the existing divisions and resulting in secession. For the first time in the country’s history, the transfer of power would not be peaceful.

Government and military institutions shuddered in the gap. The cadets at West Point were dragged into the breach. The withdrawal of South Carolina from the Union in December 1860, and other Southern states in ensuing months, prompted a wave of resignations.

James numbered among them. He would never graduate with the Class of 1863.

Instead, he made his way to Richmond. In mid-June 1861, James received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Provisional Army of Virginia, prior to its transfer to the Confederate States Army.

James joined the staff of fellow Virginian Joe Johnston, West Point Class of 1829. The veteran general now commanded the Army of Northern Virginia. James proved his value as an aide de camp at the Battle of Manassas. Johnston praised him and other aides in his after-action report: They “conveyed my orders bravely and well on their first field.”

Johnston designated James to deliver the official report of the battle to authorities in Richmond, along with captured battle flags. Accompanying James on the mission of honor was an aide on Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard’s staff.

On the Union side, recent West Point graduate Custer, now a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, carried messages to Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell. There is no evidence that he and James were aware of each other’s presence.

The symbolism of a descendant of George Washington delivering captured U.S. Army flags and the official report of victory at Manassas to the Confederate capital could not have been lost on Johnston. It easy to imagine that some saw it as an omen of ultimate success of the Southern war for independence, a second American Revolution.

A year later, Johnston did not mention James’ capture in his official report of Seven Pines. Nor did Johnston reference James in his 1874 book, Narrative of Military Operations, Directed During the Late War Between the States.

Capture at Seven Pines, reunion with Custer

The morning of May 31, 1862, dawned bright and sunny after a night of torrential thunderstorms and bursts of lightning in the vicinity of Seven Pines. Three-quarters of a mile from the intersection of the Williamsburg and Nine Mile roads, a soggy division of raw, untested Union troops in the vanguard of the army made the best of a muddy situation in hastily-dug rifle pits and a crude redoubt. About a third of a mile in front of this line, detachments of soldiers constructed abatis. Nearby pickets watched for Joe Johnston’s boys.

The general in command of this sector, Silas Casey, West Point 1826, had proved a poor cadet, graduating near the bottom of his class. Since then, he had distinguished himself in various actions in Florida, Mexico and the West. Just a few months earlier, his three-volume manual for soldiers, Casey’s System of Infantry Tactics, adapted earlier guides to brigade and division formations. It became popular in both armies.

On the right flank of Casey’s division, alert pickets observed an officer in gray along the edge of an open field and nabbed him.

James Washington had just become a prisoner of war.

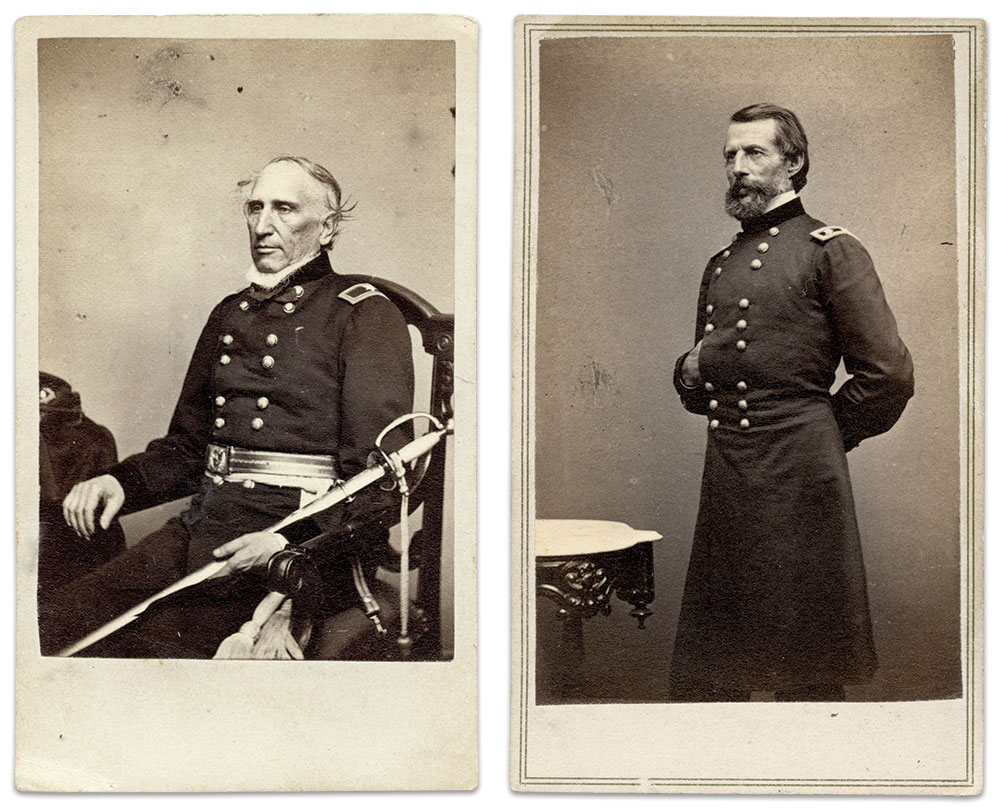

The pickets hustled their prize off to Casey’s headquarters and explained the situation. Casey understood the value of the prisoner. Without missing a beat, he accompanied the group, along with Col. Lewis C. Hunt of the 92nd New York Infantry, the general officer of the day, to the headquarters of Casey’s superior, Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes, commander of the 4th Corps. Keyes, who had graduated in the top quarter of the Class of 1832, had split his pre-war career between staff duties, instructing cadets at his alma mater, and active duty at remote outposts along the Pacific coast. Keyes had recently taken the helm of the newly formed 4th Corps.

A line of pickets with James under guard, and Casey and Hunt in tow, marched into Keyes’ headquarters and located the general. They turned over the prisoner for questioning.

Keyes recounted what happened next in his after-action report. “While speaking with the young gentleman, at the moment of sending him away, a couple of shots fired in front of Casey’s headquarters produced in him a very evident emotion. I was perplexed, because having seen the enemy in force on the right when the aide was captured, I supposed his chief must be there. Furthermore, the country was more open in that direction and the road in front of Casey’s position was bad for artillery. I concluded therefore, in spite of the shots, that if attacked that day the attack would come from the right.”

Keyes picked up another bit of intelligence from Col. Hunt, who reported he heard train cars running through the night from the direction of the enemy.

Brigadier generals Silas Casey and Erasmus D. Keyes gained valuable intelligence during their interrogation of Washington, then sent him under guard to Army of the Potomac headquarters.

A member of Keyes’ staff, Medical Director Frank H. Hamilton, observed James’ interrogation and confirmed the veracity of the general’s report. “While General Keyes was conversing with him, two shells passed over us, proceeding apparently from the enemy’s lines on the left. Young Washington looked around and towards his own lines in a manner indicating restlessness, and perhaps expectation of immediate succor.”

Keyes, convinced that a Confederate attack was imminent, fired off two missives to the headquarters of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commanding the Army of the Potomac.

The first, to McClellan’s Assistant Adj. Gen. Seth Williams, stated, “The capture of one of Gen. Johnston’s aides on our right this morning, and the running of cars through the night, all indicate that the enemy is turning his attention towards this position.”

The second, repeating the substance of the first with additional detail, was carried to headquarters by one of Keyes’ aides, 2nd Lt. Bradbury C. Chetwood. James, who remained in custody of guards, accompanied Chetwood to headquarters.

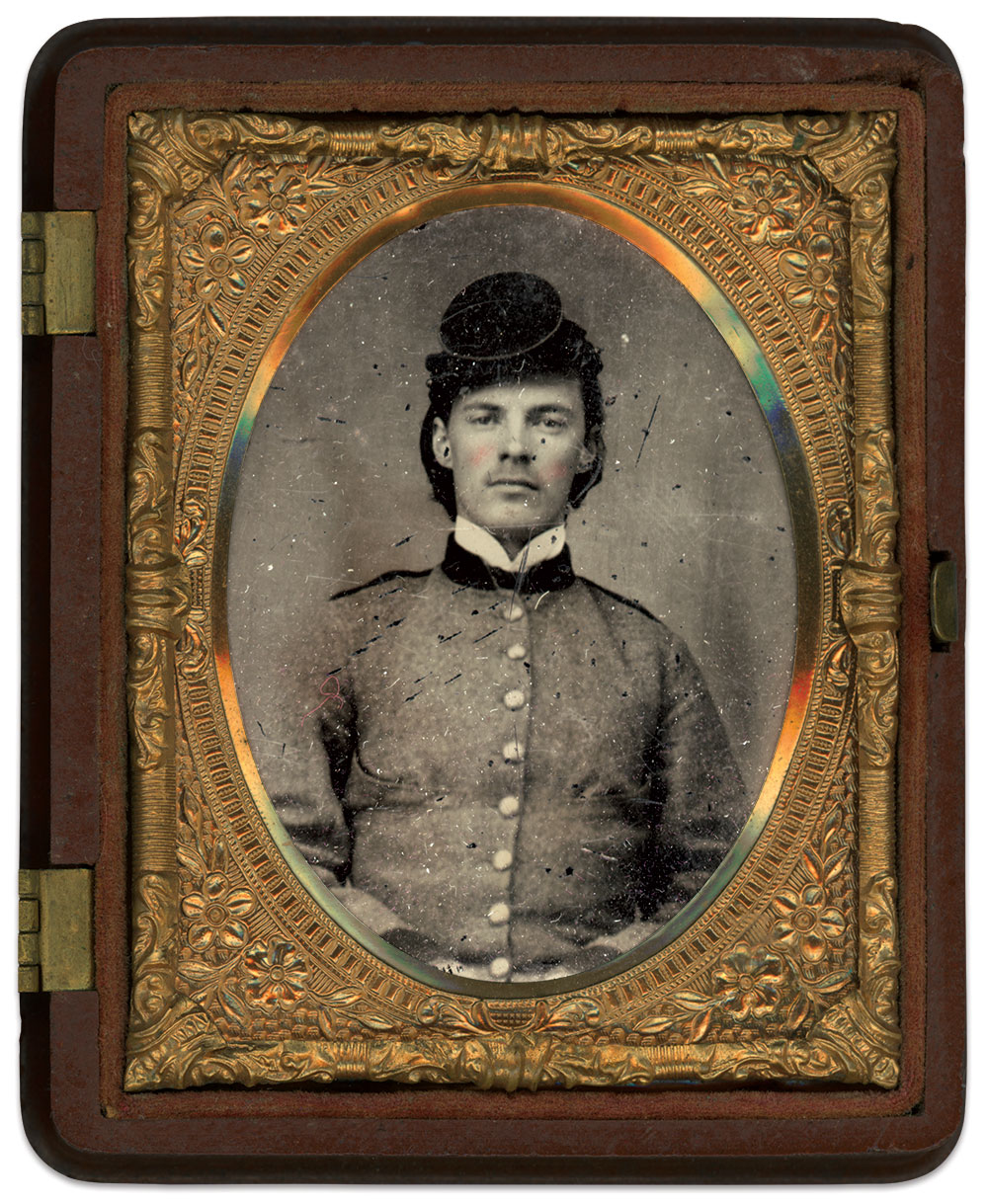

The Liljenquist Family Collection at the Library of Congress.

Many years after the war, Gen. Longstreet offered his opinion on why James did not fulfill his original mission. “The order was sent by Lieutenant Washington, of Johnston’s staff, who, unused to campaigning, failed to notice that he was not riding on my line of march, and rode into the enemy’s lines. This accident gave the enemy the first warning of approaching danger; it was misleading, however, as it caused General Keyes to look for the attack by the Nine Mile road.”

James arrived at McClellan’s headquarters while Keyes, Casey and the rest of the 4th Corps prepared for a bruising fight later in the day in the forests and fields around Seven Pines.

Word of James’ capture traveled quickly. One of McClellan’s aides de camp, a recent addition to the general’s staff, was none other than George Custer. He revealed in an undated letter that he “heard that a Confederate officer knew him and had said that he knew me and would like to see me. I went immediately to the place where he was under guard and found to my delight it was my West Point friend Washington.”

Custer continued, “After a joyous meeting and the best welcome I could give him, I left and went to General McClellan to ask consent to his being put on parole that he might afterwards become my guest. The request was granted and I hastened back to tell Washington and invite him to my tent. I entertained him for some days and we had so much of interest to tell each other,” adding, “During the stay we talked over the different engagements, the prospects of the future and found time to recall those halcyon days at West Point.”

Custer recounts the story of the portrait

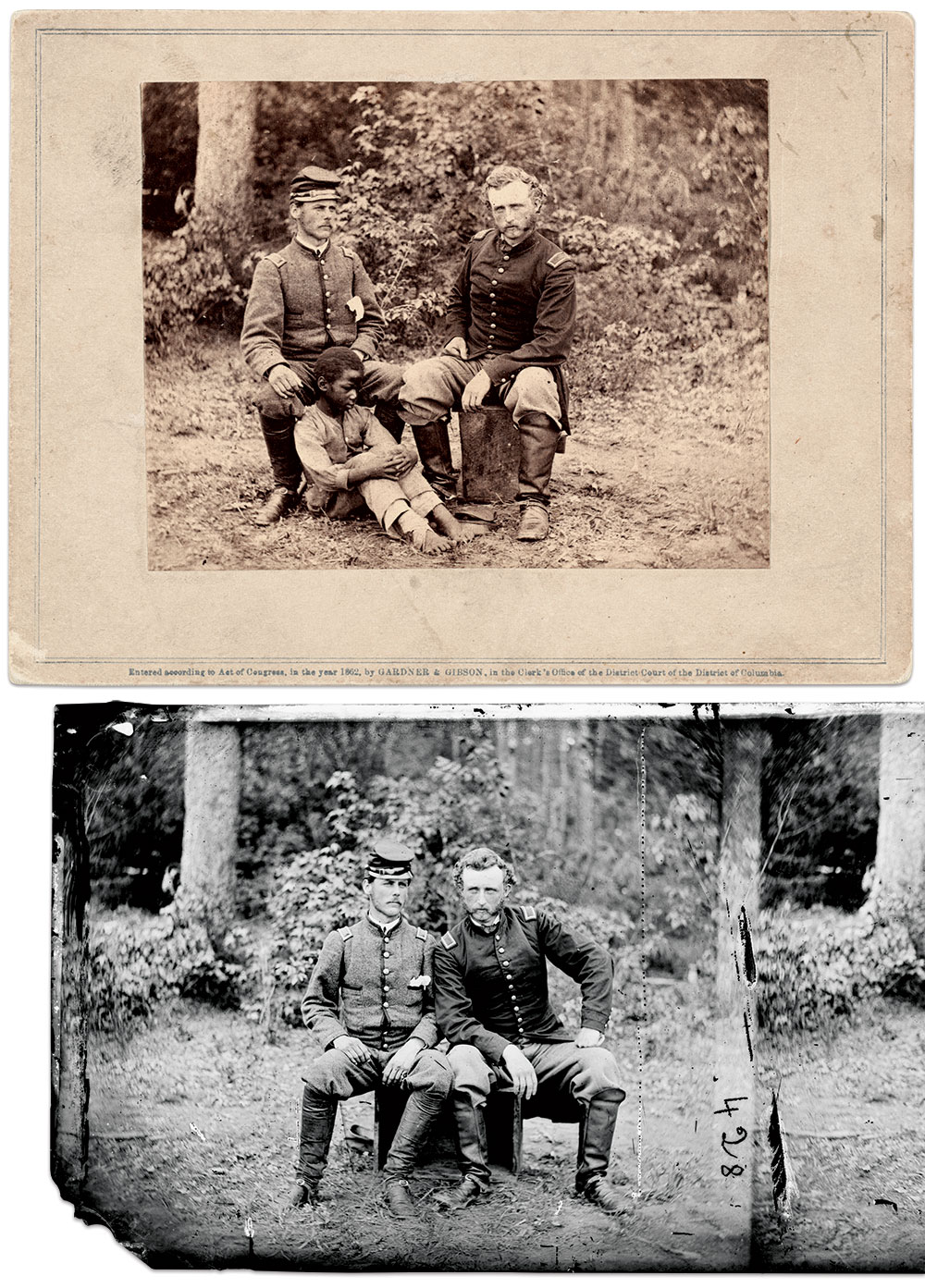

In the same letter, Custer recounted how he and James came to sit for their portrait. Custer noted that the army was “laying quiet,” an indication that the immediacy of the Battle of Seven Pines had passed. “A strolling artist came through camp taking photographs. Washington and I thought we would sit together for a picture.”

Custer also explained how the child came to pose with them. “As we took our places Washington called a little contraband, who stood with open mouth gazing at the camera, to come to him and said to me, ‘Custer, suppose we make him one of the group and it would be the thing wouldn’t it to put him nearest me,’ laying stress on the words to indicate his pronounced opinions on the rights of the South to claim the Negro.”

Custer laughed. “I suppose so,” he replied to James.

Custer’s reaction is hard to read, other than an acknowledgment of the underlying truth of James’ words, which reflected the Washington family’s generational ownership of enslaved people.

The child, according to Custer, was instructed to sit at James’ feet. Custer, however, does not identify who gave this instruction. He also does not mention a second photograph taken without the child. The glass negative of this pose, a stereoview, is in the Library of Congress. Its presence raises the question of the order in which the pictures were taken. Custer’s account notes that the idea of including the child came to Washington as the two men were taking their places, a strong indication that this pose came first.

The Custer account does not name the artist responsible for the photographs. The Library of Congress’ negative is credited to James F. Gibson, who roamed the camps in the wake of Seven Pines. Surviving albumen photographs and stereo cards are imprinted with the names of Gibson and Alexander Gardner on the card-stock mounts. Both men worked with Mathew B. Brady and his team of photographers.

Gibson’s ubiquitous presence with the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign is well-documented in surviving images. His view of wounded soldiers at a Union field hospital at Savage’s Station is one of the better known during the months-long campaign.

Brady displayed a selection of war images documenting the movements and soldiers of the Army of the Potomac from Bull Run through the Peninsula Campaign at his New York City gallery. Cartes de visite of the various scenes, and of generals and their staffs, were available for sale to visitors. A review of the exhibit appeared in the July 22, 1862, edition of New York City’s The Evening Post. It stated, in part, “Every battle-field of the present, as of every war, has its national history. But, besides this, there is a private interest felt by different individuals in these places; for in one a brother fell; in another a lover lost an arm; and in others friends and relatives have fought bravely and come out unhurt. Of these places Brady’s cartes give a better idea than volumes of description could do.”

As we took our places Washington called a little contraband, who stood with open mouth gazing at the camera, to come to him and said to me, ‘Custer, suppose we make him one of the group and it would be the thing wouldn’t it to put him nearest me,’ laying stress on the words to indicate his pronounced opinions on the rights of the South to claim the Negro.”

— George Armstrong Custer

Was the image of James and Custer featured in the exhibit?

Possibly. The Evening Post review mentions only the presence of portraits of generals pictured singly or with their staffs.

Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, recalled that it received attention in England. “General Custer told me of his surprise on hearing afterwards of the final destination of this photograph that had been taken only to beguile a weary hour and be a parting keepsake for each one, from his friend to himself. Some person, unknown to the General, obtained this photograph from the artists and sent it to England. It was printed in the London Illustrated News, without the names of the sitters, a Latin motto underneath called it ‘Both sides of the war and the cause of the war.’”

The image, however, does not appear in any issues of the London Illustrated News from June 1862 through December 1865. Several 20th and 21st century historians stated it appeared in Harper’s Weekly. A search of issues from the same period turned up nothing.

Further investigation reveals the publication was most likely The Times of London. Its Aug. 30, 1862, issue features a commentary titled “American Photographs” that offers a look at war photography in the United States. No photographs are reproduced. The narrative has two parts. The first is an overview of war photography in England, France, and America. The second and more relevant section to this story is a review and critique of Brady’s Peninsula Campaign scenes and portraits.

The anonymous reviewer described the image of James, Custer and the child. The wording of this description indicates that the reviewer had access to a copy of the photograph on the imprinted mount that misspelled Custer’s name as “Custis.” Also of note is the use of the Latin phrase “teterrima causa belli,” or “the most terrible cause of war.”

“The most agreeable subject in the volume perhaps is one of a Confederate lieutenant, of the Washington family and name (for all the representatives of the Pater Patrice are and were Secessionists) who was taken prisoner, sitting beside his college friend and relation, Captain Custis, of the United States’ army; while a negro boy, barefooted, with hands clasped, is at the feet and between the knees of his master, with an expression of profound grief on his shining face. The Confederate, in his coarse grey uniform, sits up erect, with a fighting bulldog face and head; the Federal, a fair-haired, thoughtful-looking man, looks much more like a prisoner; the teterrima causa belli, who appears to think only of his master, is suggestive enough.”

The Times reviewer grasped the dual narrative. The photograph tells the story of two classmates divided by war. It is also the story of the moral conflict and politics behind the war.

The reviewer assumed the child was an enslaved boy owned by James, which is understandable as the proximity of the pair suggests a familiarity between the two. There is no reason to doubt Custer’s statement that the child was a contraband in camp with no direct connection to James. Aside from this presumption, the reviewer accurately interpreted James’ intent. James succeeded in communicating to the reviewer that in his view slavery was the underlying cause of the Civil War.

Epilogue

James’ stay with Custer at McClellan’s headquarters lasted about two weeks. On June 20, James joined the population of prisoners of war at Fort Delaware, Del. His arrival prompted this reaction in a report published a day later in The Philadelphia Inquirer: “He is small in person, light haired and light mustachioed. His comely face, beaming with gentleness, excites strong prepossessions in his behalf.”

In other words, he was a handsome young man.

Fort Delaware became James’ home for about three months. On September 21, at Aiken’s Landing, Va., he gained his release as part of a prisoner exchange. The officer swapped for him, 1st Lt. James S. Baer (1834-1917) of the 1st Maryland Infantry, had suffered a wound and fallen into enemy hands at Front Royal, Va., in May 1862.

James returned to Johnston and resumed his staff duties in the Department of the West and the Army of Tennessee. In April 1864, James transferred to the Ordnance Department of the arsenal at Montgomery, Ala., where he served as executive officer.

The reason for his transfer: Alabama resident and young widower Jane Bretney Lanier. Born in Mississippi and reportedly descended from Patrick Henry and Dolley Madison, Jane married James in February 1864. In March 1865, during the war’s waning weeks, Jane gave birth to a son, William Lanier, in Montgomery. The following year in Baltimore, they brought a second son, Benjamin Cabell, into the world. Two more children followed.

In October 1866, President Andrew Johnson granted James a full pardon for his Confederate allegiance during the war.

James went on to become an executive in the lucrative railroad industry, notably with the Baltimore and Ohio in Pittsburgh. In early 1900, he fell seriously ill with an undisclosed illness that required an operation at a Pittsburgh hospital. He died a few days after the procedure, surrounded by his family. They inherited a princely estate valued at $100,000 (about $3.6 million in today’s dollars). James’ remains were brought to Baltimore and interred in Green Mount Cemetery. Jane joined him in death a year later, and is buried by his side.

By this time, James’ father had been long dead. Lewis Washington passed in 1871. A year later, his widow sold George Washington’s sword and pistol, and some of the other relics displayed at Beall-Air, to the New York State Library for $20,000. Four decades later, in 1911, a fire in the library seriously damaged the sword.

James’ son William sold the remainder of the Washington relics at public auction in 1917. He died in 1933 without surviving children.

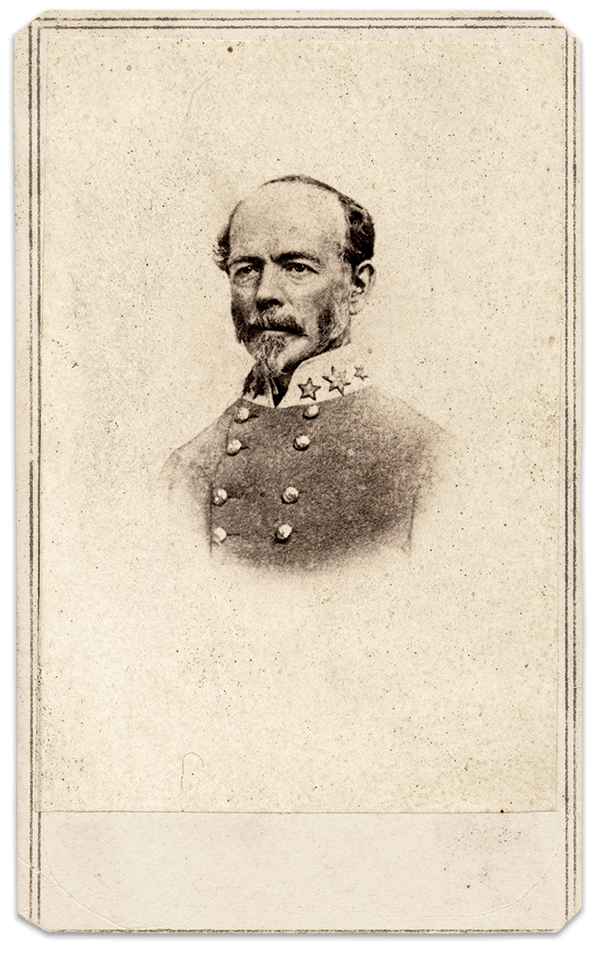

The fate of Joe Johnston and the Confederate army in the East took a dramatic turn just hours after James wandered into the Union pickets. About sunset at Seven Pines, towards the end of the first day’s fight, the general rode his horse within range of enemy fire. A musket ball hit him in the right shoulder. Moments later, a shell fragment struck him in the chest, knocking him off his horse. Carried from the field, command of the army passed to Gen. Robert E. Lee.

On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia. When Johnston learned of this development, he opened negotiations with his counterpart, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. About two weeks later, on April 26, Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee and all Confederate forces active in the Southern states along the Atlantic coast.

Johnston, like James, went on to a career in railroads. He famously acted as a pallbearer at the 1891 funeral of Sherman, where he caught a cold that led to pneumonia and his death. James sent his condolences to the family. Johnston is buried in Baltimore’s sprawling Green Mount Cemetery, the same place where James’ remains rest. The plots sit separated by about 330 yards, or a six-minute walk.

Brigadier General Silas Casey’s inexperienced division was driven from the field in confusion at Seven Pines by a Confederate division commanded by Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill. McClellan blamed the rout on Casey, relieved him from command, and kept his troops out of combat for the remainder of the campaign. Casey’s friends came to his aid. He received a promotion to major general dated May 31, 1862, but his days as a field commander were over. He retired from the U.S. Army in 1868 and died in 1882.

McClellan’s days in the field were also numbered. Relieved of command before the end of 1862, he contributed to his downfall by aggressive, antagonistic dealings with President Lincoln and his administration in stark contrast to his dilatory tactics in war. McClellan ran for president against Lincoln in 1864 and lost.

George Armstrong Custer’s star continued to rise following the Peninsula Campaign. His charisma, flamboyant uniforms, and aggression to the point of recklessness added to his charm and popularity. Following his death in combat against Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, wife Lizzie’s writings solidified his legacy as an American hero. James corresponded with her along the way. She died in 1933, the last of the key players in the story of the photograph of Custer, James and the child.

There is no evidence that James and Custer saw one another again after the brief reunion on the Peninsula forever memorialized by the photograph. According to Lizzie, Custer did visit Beall-Air later in the war. He arrived to find the stately manor somewhat worse for wear, and a servant with a message from the lady of the house for the general to come inside. Custer did, and met James’ stepmother, Ella, only five years his senior.

Ella apologized for the little hospitality she had to offer due to the war, “but that her son had told her that General Custer would doubtless pass near on some of his raids and she must surely take occasion to invite him to their home. She expressed much gratitude for the kindness he had shown to her son during his imprisonment.”

References: Smith, The Battle of Seven Pines; Johnson and Buell, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 2; Baltimore Daily Commercial, Dec. 5, 1844; The Evening Star, Washington, D.C., April 30, 1889; U.S. Census Slaves Schedules, 1850 and 1860; The Sun, Baltimore, Md., March 7, 1900; Hallowell, Autobiography of Benjamin Hallowell; Schaff, The Spirit of Old West Point; Merington, Ed., The Custer Story: The Life and Intimate Letters of General George A. Custer and His Wife Elizabeth; Reynolds, The Civil War Memories of Elizabeth Bacon Custer; Wayland, The Washingtons and Their Homes; Roseberry, A History of the New York State Library; Report of the Select Committee of the Senate appointed to inquire into the late invasion and seizure of the public property at Harper’s Ferry; George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Steel-Hilted Smallsword: Dr. Erik Goldstein discusses the design and history of George Washington’s smallsword.” (mountvernon.org/preservation/collections-holdings/washingtons-swords/the-steel-hilted-smallsword); Richmond Enquirer, July 2, 1861; Official Records; Johnston, Narrative of Military Operations, Directed During the Late War Between the States; American Medical Times, Aug. 30, 1862; Report of Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, The Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress; Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America; The Evening Post, New York City, July 22, 1863; The Times, London, England, Aug. 30, 1862; The Photographic Journal, London, England, Dec. 15, 1862; The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 21, 1862; The Sun, Baltimore, Md., Oct. 15, 1862.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Lieutenant Washington’s Fateful Encounter: James Barroll Washington sat for a well-known portrait with George Armstrong Custer. Here’s the story behind it.”

Comments are closed.