By Ronald S. Coddington and Nicholas Penachio, with images from the authors’ collections

What if the Civil War had been the short affair many Americans initially believed? Imagine Bull Run and other engagements in the East and West as Union victories. The Battle of Ball’s Bluff in October 1861 is the final clash of arms. The rebellion dissolves.

Grant never demands unconditional surrender. Pickett doesn’t charge. Hooker’s men do not advance above the clouds. Farragut never damns the torpedoes. The stars of Sherman, Custer, and Sheridan never rise.

Of course, this is not how the war played out. But a series of distinctive melainotypes designed to be worn on clothing and other items makes the scenario outlined here seem plausible. Produced by Abbott & Company in 1861, these melainotypes are a unique snapshot of the earliest part of the war. The hybrid nature of the series—part badge, part photo—does not easily fit into a single classification, and its brief lifespan may explain why they have been largely forgotten.

Yet the series is a remarkable visual documentation of individuals who shaped the war and popular culture. It is also representative of the mass production of hard plate photographs before the rise of paper.

How these distinctive images, known today as Abbottypes, came into existence is as fantastical as a short Civil War.

Only this story is true.

When glass and iron giants roamed the world

The origin of Abbottypes dates to ten years before the Civil War, when a new process revolutionized photography. In 1851, Englishman Frederick Scott Archer introduced the collodion process, named for the chemical solution at its core. Glass plates coated with collodion and exposed to light through the camera’s lens resulted in negatives with a stunning level of clarity and detail. They also eliminated distracting reflections cast by the silver-surfaced plates of the daguerreotype process that had dominated the industry since its introduction in 1839.

By March 1852, Archer established two simple methods to make the glass negative into a positive. He coated the back of the plate with black varnish, or placed black velvet behind the glass. Thus the ambrotype was born. These inexpensive, high quality glass pictures sounded the death knell of the daguerreotype process, which slowly slid into technical oblivion.

Curious minds in Europe and the United States experimented with applying collodion to other surfaces. One man, an American college professor, focused his efforts on sheet iron plates. Hamilton Lamphere Smith of Kenyon College in Ohio, an early devotee of photography, assisted by student Peter Neff Jr., applied dark varnish to the plates, which were then oven dried and polished. The finished plates had a hard enameled finish.

The process, known as japanning, had been used by European and American furniture makers and metal workers for centuries to imitate an East Asian lacquer technique.

Collodion applied to these japanned iron plates resulted in images that rivaled the ambrotype and the daguerreotype. Compared to glass, the iron plates were cheaper, less prone to breakage, and eliminated prep-time to file sharp edges and remove dust and other surface imperfections prior to coating with collodion and placing in the camera.

Smith and Neff shared their results in late 1855. In early 1856, Smith filed for a patent in the name of Neff and his father, William. The Neffs established a factory in Cincinnati to manufacture the plates. After fire destroyed it in early 1857, the Neffs moved the operation to the Connecticut firm of James O. Smith & Sons, makers of japanned tinware. Located in Westfield, the company also had a business office in New York City.

The younger Neff also authored a handbook to promote the new melainotype, or ferrotype, process. Within a couple years, melainotypes gained traction and popularity in a competitive marketplace that included its more expensive cousins, ambrotypes and daguerreotypes. The family of hard plate processes shared a common foundation—all were negative images made into positives and produced one at a time.

A fusion of melainotypes and buttons

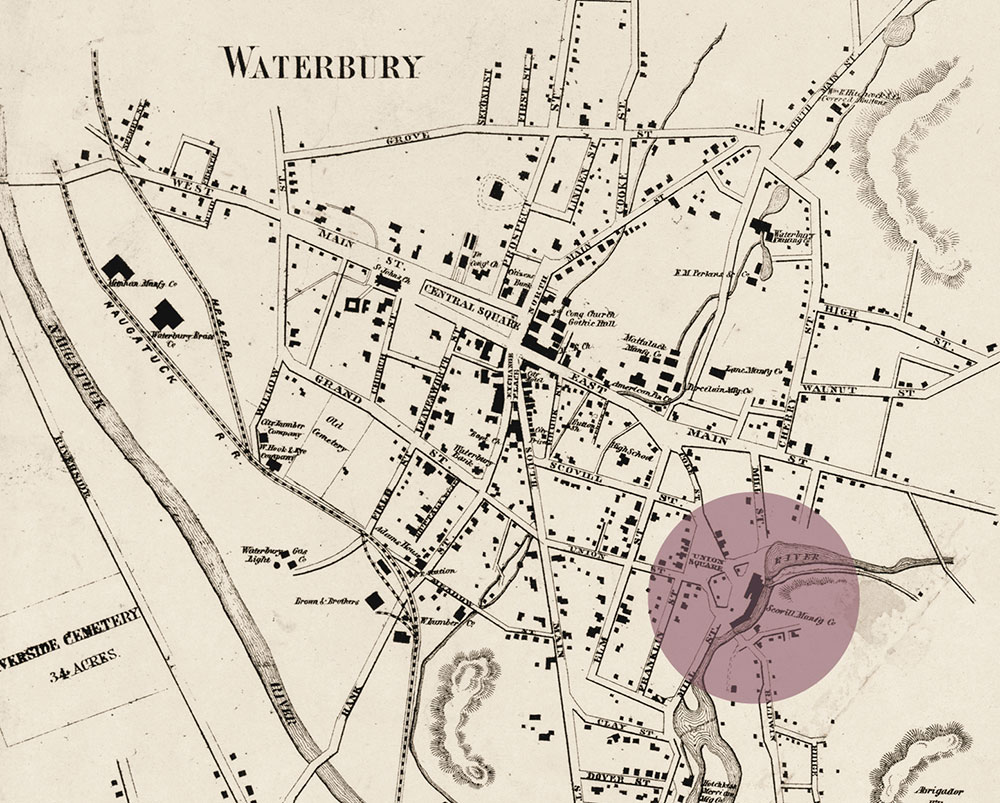

Thick smoke poured from tall brick chimneys towering above the sprawling complex of the Scovill Manufacturing Company in Waterbury, Conn. A beehive of activity located a score of miles west of the Smith factory in Westfield, Scovill traced its origins to the dawn of the century. Over the decades and various mergers and acquisitions, the company built its brand as a leader in brass production and button making.

In 1842, Scovill expanded operations into the nascent photography industry. As the daguerreotype exploded on the American scene and galleries popped up across the country, Scovill supplied photographers with plates, mats, preservers, cases, and other necessities. The company kept pace with the times, adding ambrotype supplies and, by 1858, melainotype plates.

Consumer demand for photographs fueled innovative entrepreneurs to experiment with a fusion of buttons and photographs. The April 1860 issue of Humphrey’s, a photographic journal, published a letter by Waterbury photographer William S. Kelly, who noted his involvement in providing melainotypes for buttons. Janice G. Schimmelman, the author of Tintype in America 1856-1880, noted that most of Kelly’s photographs were produced from engravings of adorable girls, and that he probably worked for Scovill.

Kelly mass-produced melainotypes to meet the public’s increasing appetite. At first glance, creating melainotypes at high volume seems impossible and in direct opposition to the spirit and artisanal nature of hard plate photography.

How did Kelly do it? Though he left no record of his method, a letter published in the October 1860 issue of Britain’s The Photographic News describes an ingenious process used to scale melainotype production from singles to thousands for buttons. The writer, noted photographer Paul Eduard Liesegang, experimented with collodion positive processes and published the journal Photographisches Archiv beginning in 1860. Liesegang claimed that “hundreds of grosses of these little pictures are produced every day.”

Liesegang’s method began by mounting 100-150 lithographic portraits upon a large board, then photographing it on a glass plate coated with specially prepared collodion. The glass was removed from the camera and developed to produce a strong, contrasty collodion positive image. Before the collodion dried, a piece of fine paper was wetted, then pressed against the collodion glass surface. The paper, with the collodion positive layer, was carefully removed from the glass, cut into individual images, and then pressed onto a japanned metal melainotype plate. When the paper was peeled back, the collodion positive image adhered to the plate. The transfer was complete. The melainotype was varnished to protect the image and cut into small rounds to fit into button rims. Liesegang boasted, “You can conceive that in this manner a photographer having a man to prepare the plates, and another to transfer the film, can produce an immense number of pictures in one day.”

Liesegang did not explain how the melainotype mass production method came into existence. One possibility is that it originated in Waterbury and was communicated by letter to Germany. If true, the likely letter-sender may have been one of Kelly’s fellow photographers, William Delius, a German immigrant, who fulfilled a thousand-dollar order for photographs from a source in his homeland. That source may have been Liesegang or someone connected to him.

Kelly worked at a similar scale. By one account, Kelly produced 4,000 dozen melainotypes in a single day. The wording suggests that Kelly processed 4,000 melainotype plates, each containing a dozen images, for a grand total of 48,000.

The fashion for wearable melainotypes quickly spread from adorable girls to portraits of prominent individuals available in an array of styles in addition to buttons, including medals, badges, watch charms, shields and frames.

Abbott Brothers: campaign medal agents

When Anson Fletcher Abbott arrived in Waterbury about 1850, he entered the epicenter of the nation’s brass production. Pins, clocks, buttons, and other products rolled out of factories and on to store shelves across the country. A Connecticut native about 20 years old, Anson, a confirmed optimist, landed a position in the retail arm of one of the city’s brass leaders, the Benedict & Burnham Manufacturing Company. As B&B expanded, it spun off subsidiary companies, including the American Pin Company, The Waterbury Clock Company, and the Waterbury Button Company.

In 1852, B&B and the other major brass maker in town, Scovill, cofounded a brokerage to manage sales. The new firm, Benedict & Scovill, operated out of offices in Waterbury and New York City. Anson joined B&S as its secretary. He also became treasurer of Waterbury’s Savings and Building Association. The bank’s directors included a member of the Scovill family.

Anson built his business acumen on experience gleaned from the brokerage and bank. In 1860, at about age 30, he embarked on his own business venture with his older brother, Charles Sherman Abbott, who had worked as a printer. The Abbotts operated as a wholesaler of photographic presidential campaign medals to retail outlets.

Though the manufacturer of the campaign medals is not exactly known, the likely candidate is Scovill. The melainotypes were probably mass-produced in Waterbury by the aforementioned Kelly and Delius, and perhaps other photographers.

The Abbott Brothers had competition. Advertisements in 1860 newspapers reveal other agents, including K. Cruger of New York City, Hosea B. Carter & Company of Boston, and Levi Cone of Poultney, Vt.

The business proved highly lucrative. Sales of buttons, badges and medals skyrocketed during the hotly contested presidential race with four major candidates competing against the backdrop of a fraught nation teetering on the brink of dissolution. According to a report in the Sept. 3, 1860, issue of the Hartford Courant, campaign medal manufacturers in Waterbury brought in $75,000 a day in revenue, or $2.7 million in today’s dollars.

Scovill and other Waterbury firms were not the only manufactures to jump into the campaign medal craze. In mid-August 1860, Cincinnati’s J.K. Lanphear & Company placed help wanted ads for agents with estimated earnings from $3 to $8 per day, or $107 to $285 today.

The earliest known reference to the Abbott Brothers appeared in the Aug. 9, 1860, edition of Ohio’s Perrysburg Journal: “We have received from Messrs. Abbott Brothers, agents, No. 742 Broadway, N.Y., a campaign medal, containing likenesses of Honest Old Abe and Hannibal Hamlin, our gallant standard bearers. The medal is about the size of an American quarter dollar, beautifully executed and is gotten up at prices varying from 5 to 50 cents.”

Two days later, Harper’s Weekly published the Abbott’s earliest known advertisement. The first section of the two-part write-up offered bulk sales of photographic medals for the presidential campaign. The second section promoted a button featuring the Prince of Wales, who, with an entourage, was in the first half of a four-month visit to the United States. The button of his royal highness indicates that the Abbott Brothers glimpsed a future for wearable melainotypes beyond politics.

Abbott & Company: Union button sellers

Enthusiasm for photographic buttons continued after twin shocks of secession and armed rebellion unleashed a tidal wave of patriotism. The Abbotts met the moment with wearable melainotypes that magnified the allegiance of citizens to the Union and the Constitution.

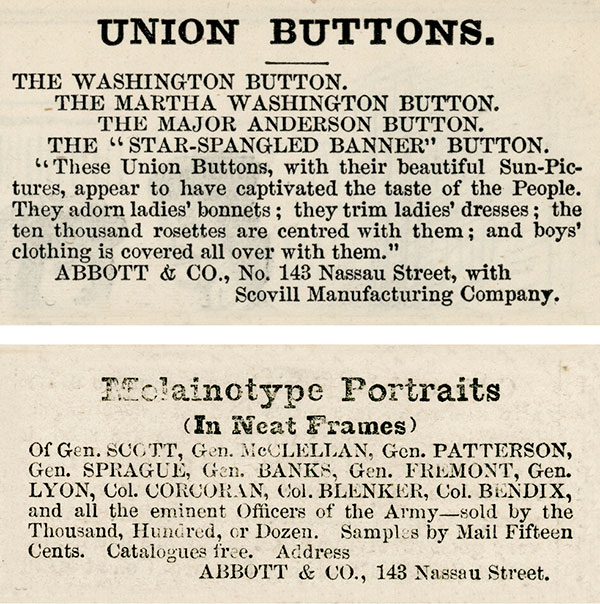

On May 18, 1861, an advertisement placed in Harper’s Weekly by the Abbotts promoted buttons featuring the North’s first hero, Maj. Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame, as well as George and Martha Washington. “These Union Buttons, with their beautiful Sun-Pictures, appear to have captivated the taste of the People. They adorn ladies’ bonnets; they trim ladies’ dresses; the ten thousand rosettes are centered with them; and boys’ clothing is covered all over with them.”

issue of Harper’s Weekly.

A line at the bottom of the advertisement, “Abbott & Co., No. 143 Nassau Street, with the Scovill Manufacturing Company,” establishes that the brothers formed a company and a connection to Scovill. The address is also noteworthy. The New York City business directory for 1861-1862 lists two lower Manhattan locations for the offices of Abbott & Co.: the 143 Nassau Street referenced in Harper’s Weekly and 36 Park Row. The locations are only a block apart. Scovill also maintained offices at 36 Park Row. They had a second location at 4 Beekman Street, located midway between 36 Park Row and the Abbott’s office at 143 Nassau Street.

Anson and Charles are listed in the directory as being in the melainotype business. Anson’s home is listed as Connecticut, suggesting he worked out of Waterbury and perhaps made the occasional 90-mile commute to the Manhattan offices. Charles resided at 21 Stuyvesant Place on nearby Staten Island.

Abbottypes: a survey

Readers of the Aug. 3, 1861, issue of Harper’s Weekly were confronted with a wall of war coverage, including a full-page woodcut engraving of the recent Union debacle at the Battle of Bull Run. On the last page, a small Abbott & Company advertisement titled “Melainotype Portraits (In Neat Frames)” promoted bulk sales of portraits of familiar Union army senior officers and popular military figures in New York City. Interested parties could obtain a catalog and samples.

Today, these framed melainotypes are known as Abbottypes, a portmanteau of Abbott and melainotype. Exactly when Abbottype entered the vocabulary is not known. Wes Cowan, American anthropologist, auctioneer and antiques appraiser, recently observed “I’ve been dealing for nearly 30 years and have always heard this term.” A likely explanation is that its origins are linked to the modern collecting community that traces its roots to the Civil War centennial.

A survey of 122 surviving Abbottypes reveals the characteristics of the format:

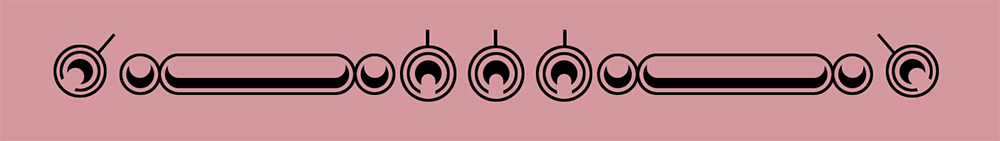

Size: Abbottypes measure about 1 3/8 wide and 1 5/8 inches long. These dimensions suggest the melainotypes were cut from a full-size iron plate divided into four columns and five rows of portraits, or a 20th plate. Each is housed in a frame. A thin piece of paper identifying the subject is inserted in the back between the plate and the frame.

Portraits: The likenesses are drawn from a variety of sources: photographs, paintings, engravings and drawings.

Frames: The frames are thin brass preservers generally consistent in shape and size. They feature scalloped embellishments in each corner and in the center of each side. Along the top center edge, a small curved loop secures a brass ring for wearers to attach to clothing, hats and other items. A survey of frames indicates two variations. The most common by a wide margin is a brass loop into which was inserted the ring. A very small number have no loop, and a portion of these have two holes punched into the preserver to connect the ring. The rings are standard in size, though most are missing from surviving examples.

Unlike other framed, larger-sized melainotypes of the period, no cover glass protects the plate. This omission is likely due to a need to keep them as light as possible because the weight of the glass could cause lighter garments to sag. Breakage could also be an issue. There also must have been financial and manufacturing considerations.

Inserts: The printed paper inserts were available in an array of colors. The survey documents that 73 percent are pink. Another 20 percent are green or blue. The remaining 7 percent are yellow, purple, violet, red or orange.

The inserts feature decorative borders. The survey reveals four styles. The most popular, a pattern of bars and circles, appears on 81 percent. A chain link motif appears on 11 percent and a double-line design on 7 percent. One insert features a series of interlocked circles.

The name of the subject always appears prominently on the insert. A descriptive label below the subject’s name is found on 58 percent of the Abbottypes in the survey. The labels fall into two categories. The majority are titles (General Sickles) or connected to a geographic location (Gov. Sprague, of Rhode Island). A smaller number are inspirational (Lieut.-Gen. Winfield Scott, Faithful to the last. Ever young in the service of his country).

The Abbott name and Nassau Street address is listed on 68 percent of the images surveyed. One of the inserts, for Col. James H. Perry of the 48th New York Infantry, lists the Abbotts in Waterbury. There appears to be no discernible reason why some include the name and address and others do not. But an analysis by subject—military, political, religious, media, founding fathers and European notables—reveals one clear pattern: None of the Confederate military leaders include the Abbott imprint. The remaining categories, however, are divided.

The Abbott name and Nassau Street address is listed on 68 percent of the images surveyed. One of the inserts, for Col. James H. Perry of the 48th New York Infantry, lists the Abbotts in Waterbury. There appears to be no discernible reason why some include the name and address and others do not. But an analysis by subject—military, political, religious, media, founding fathers and European notables—reveals one clear pattern: None of the Confederate military leaders include the Abbott imprint. The remaining categories, however, are divided.

One anomaly is Father John J. Hughes, the Irish Catholic Archbishop of New York City. The imprint on his insert is D.&J. Sadlier & Company, a major publisher of Bibles and other religious materials. The company owners, Irish immigrants Denis and James, advertised their office on 164 William Street in Manhattan, just a five-minute walk from the Abbotts. It is possible that the Sadliers printed the inserts for the Abbotts, and may have attempted a foray into the wearable melainotype market with the likeness of the beloved archbishop.

Overall, 52 percent of the Abbottypes surveyed include inserts that are pink, bordered with the bar and circle design, and have the Abbott imprint.

Timeframe: The Abbotts appear to have made selections based on coverage in New York City’s daily newspapers and Harper’s Weekly between April and November 1861, according to a review of the subjects in the survey, and their accompanying titles and descriptive labels printed on the inserts. The brothers, entrepreneurial businessmen in the afterglow of their successful venture into campaign buttons, must have understood that the window of opportunity for sales depended upon how long an individual remained in the spotlight. They likely acted quickly, perhaps within hours or days of a reported news event, to bring Abbottypes to market before the press and public moved on to the next headliner. They operated with the knowledge that they could quickly fulfill orders thanks to mass-production capabilities of Scovill and the Waterbury photographers.

If the Abbotts worked in this manner, production began soon after the opening of hostilities in Charleston Harbor on April 12. Abbottypes of Fort Sumter garrison commander Maj. Robert Anderson, George P. Kane, marshal of police during Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riot on April 19, Col. Abram Vosburgh, the beloved commander of the 71st New York State Militia who succumbed to disease in Washington, D.C., on May 20, and Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, shot and killed in Alexandria, Va., on May 24, support a start date of April or May 1861.

The series followed military developments at a steady clip into the summer and autumn, as evidenced by Abbottypes of Lt. John T. Greble, killed in action at Big Bethel on June 10, Capt. James H. Ward of the Potomac Flotilla, who suffered a mortal wound aboard his flagship during the June 27 Battle of Mathias Point, colonels John S. Slocum of the 2nd Rhode Island and James Cameron of the 79th New York Infantry, who died on July 21 at Bull Run, Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, who fell at Wilson’s Creek on August 10, and Col. Edward D. Baker, killed at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff on October 21.

The brothers weighed in on the question of slavery with the Abbottype of William Tillman, a free Black mariner and part of the crew of the merchant schooner S.J. Waring. The Confederate privateer Jefferson Davis captured the vessel on July 7, 1861, and informed Tillman that he would be sold into slavery. Tillman led a revolt and successfully recaptured the vessel. The story made headlines, portraying Tillman as a hero.

The brothers weighed in on the question of slavery with the Abbottype of William Tillman, a free Black mariner and part of the crew of the merchant schooner S.J. Waring. The Confederate privateer Jefferson Davis captured the vessel on July 7, 1861, and informed Tillman that he would be sold into slavery. Tillman led a revolt and successfully recaptured the vessel. The story made headlines, portraying Tillman as a hero.

On the political front, the border state crisis in Kentucky caught the brothers’ attention. The series includes Abbottypes of Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice, who supported neutrality, Joseph Holt, a member of President James Buchanan’s cabinet who convinced the former chief executive to oppose Southern secession and played a key role in keeping Kentucky in the Union, and Leslie Coombs, a retired military officer and legislator who called for arms to defend the state from secessionists.

Abbottypes of Confederate envoys James M. Mason and John Slidell, who were infamously removed from the British steamer Trent while on a diplomatic mission on November 8, are the latest-dated images in the survey.

Abbottypes of Confederate envoys James M. Mason and John Slidell, who were infamously removed from the British steamer Trent while on a diplomatic mission on November 8, are the latest-dated images in the survey.

All other Confederate military and political leaders in the series are listed by name and title with no descriptive label. Their inclusion may be the result of a need to call out the enemy by publishing the faces and names of traitorous men leading the rebellion. It is easy to imagine that pro-Southern elements in the North embraced these Abbottypes, and that some of the images found their way into the hands of Confederate families in the South.

Advertisements placed by Abbott & Company support an April to November timeline. The brothers followed up on their May 18 and August 3 promotions in Harper’s Weekly with another in the August 10 issue. They advertised for local and traveling agents to sell war portraits, medals, charms and badges in the August 29 edition of The New York Times and the September 17 issue of the New-York Tribune.

Topics: The series can be arranged into topical groups: U.S. military officers, U.S. politicians, C.S. military officers, C.S. politicians, religious leaders, European royalty, media personalities, and founding fathers.

Themes: The individuals featured in the series and documented in the survey connect to broad themes that dominated the Northern media and national conversation in 1861.

- Building support for the war at home: U.S. military officers, especially those who achieved battlefield success or lost their lives in pursuit of victory, or those who rose to high positions of authority and commanded respect, bolstered confidence in the army and navy despite defections of officers to the Confederate military. Politicians, overwhelmingly Republican, represent a pro-Union and pro-abolition of slavery worldview.

- Reinforcing the traditions and stability of the government: Abbottypes of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin recalled the origins of the government. Late senators Daniel Webster, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun reminded Americans of the power of compromise. A memorial portrait of Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas published after his death on June 3, 1861, honors the passing of President Abraham Lincoln’s worthy adversary and underscored the value of loyal opposition who battled with written and spoken words rather than violence. The descriptive text printed on the insert of Lincoln’s Abbottype, “firm to maintain and defend the Union” reassured citizens that the chief executive would do everything in his power to sustain the nation.

- Encouraging volunteerism for the military: The faces and names of army and navy officers, career and volunteer, who paid the ultimate sacrifice in battle stirred the patriotism of men and women by reinforcing the narrative of glory, martyrdom, and good Christian death in service of preserving the Union and constitution.

- Humanizing adversaries: The faces of Jefferson Davis, P.G.T. Beauregard, Robert E. Lee and other Southern military and political leaders reminded Americans that real people, many accomplished before casting their lot with the Confederacy, led the rebellion.

- Christianity and slavery: Religious leaders in the series uniformly supported the Union but had mixed views on the institution of slavery. Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson spoke often across the country in support of the administration in a sermon that came to be known as “The Future of Our Country.” A confidant of the President and some members of his cabinet, and well-connected to reform leaders of the day, Simpson is credited with shaping moral views that influenced and empowered progressive and political leaders, notably in the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. Beloved Irish Catholic Archbishop John Hughes carried sway with the Administration in 1861, but his belief of the South’s right to maintain slavery limited his influence.

Abbottypes’ final huzzah

Abbottypes’ final huzzah

The Abbottypes of Mason and Slidell are among the last produced in the series, according to the survey. The two Confederate envoys and the related Trent Affair consumed the New York press in November 1861. Far less reported was the Battle of Belmont, fought the day Capt. Charles Wilkes hauled the diplomats off the Trent. The victory by national troops at Belmont marked the rise of a promising general, Ulysses S. Grant. To date, no Abbottype of Grant has surfaced.

Supporting this end date is the lack of advertising by the Abbotts after September 1861.

Why the Abbotts stopped after about six months in operation is a mystery.

One explanation is the emergence of photograph albums. Introduced in 1860 to hold cartes de visite, albums began a rapid rise in popular culture in 1861, as measured by newspaper advertisements. By the war’s end, it would be impossible to find a home without at least one.

The business-savvy brothers adapted Abbottypes to capitalize on the craze. They experimented with attaching melainotypes to carte de visite-sized card stock mounts imprinted with the name and title of the subject. The switch from brass preserver to card stock mount and associated labor likely had no impact on production costs. If true, the Abbotts hoped to raise their return on investment by increasing the volume of bulk sales—the same strategy that worked for them during the presidential campaign a year earlier.

The small number of surviving card stock-mounted melainotypes suggests that this approach did not catch on with the public, and therefore did not meet profit expectations. The lack of success may be connected to stiffer competition in the growing carte de visite and photograph album market than the Abbott’s had encountered with wearable melainotypes.

The small number of surviving card stock-mounted melainotypes suggests that this approach did not catch on with the public, and therefore did not meet profit expectations. The lack of success may be connected to stiffer competition in the growing carte de visite and photograph album market than the Abbott’s had encountered with wearable melainotypes.

A contributing factor may have been the war itself. By late 1861, the popular notion of a short and decisive conflict had shifted to a longer and larger war with no end in sight. This recalibration could have prompted the Abbotts to rethink the subjects chosen for the series. The possibilities of a forever war might have challenged the method by which the Abbotts selected subjects for the series, and they could not come up with an alternative plan.

Another factor to consider is a major business move by the brothers. In 1862, they opened a store in Waterbury, the “Naugatuck Valley Book-store and Art Emporium.” According to a city history, the establishment was the first and foremost of its kind in Waterbury. Earnings from the store probably outpaced income from the wholesale Abbottype business. The investment of time and daily pressure of managing a retail establishment most definitely limited their ability to focus on other projects.

Epilogue

The Abbott’s Waterbury store prospered. Two years after it opened, Anson purchased a lot and constructed a new building to house the expanding business and a post office. The Abbotts remained in the book, stationary and picture business until 1871, when Anson moved on to real estate and other investments—ending his association with photography.

Anson went on to a prosperous career in Waterbury as a real estate developer. He also worked as a fire insurance agent, which he had become involved in back in the 1850s. Income from these sources provided a comfortable life for him, his wife Nancy, whom he had married in 1852, and their family of nine children. Anson died in 1907 at age 77.

Charles’ career mirrored that of his younger brother with one exception—military service. An active member of Waterbury’s Chatfield Guard militia, he organized Company H of the 20th Connecticut Infantry and became its captain in July 1862. According to the regiment’s history, comrades remarked that he would probably gain rapid promotion. But sickness sidelined him in the training camp at New Haven, forcing the 39-year-old to resign his commission after four months in uniform. He outlived Anson, dying in 1913 at age 90.

Waterbury’s dominance in the manufacture of photographic plates became a source of pride and part of its identity. “To Waterbury belongs the credit of having created a market and demand for the ferrotype, the first having been made in this city,” reported historian John Anderson, D.D., in 1896. His use of ferrotype, the name that replaced melainotype in the 1870s, gave way to tintype in the 1880s.

And what of Abbottypes? The short-lived series of wearable melainotypes is little more than a footnote in the history of photography. Yet it deserves to be remembered as a novel experiment at the intersection of mass production of hard-plates and the dawn of paper. Abbottypes are also a cousin to presidential campaign buttons, which trace their origins to George Washington’s election and became all the rage beginning in the 1890s.

Abbottypes live on as curiosities today, appreciated by a few dedicated collectors. Considering their history, they are small miracles.

Special thanks to Wes Cowan, Jeffrey Kraus, Jeremy Rowe and Rachel Wetzel.

References: Penachio, “Research on Abbottypes and Abbott & Company, 143 Nassau Street, New York City, During the Early Part of the Civil War”; Schimmelman, Tintype in America 1856-1880; Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography; Waldack and Neff, Treatise of Photography on Collodion; Anderson, ed., The Town and City of Waterbury, Connecticut, Vol. II; Humphrey’s Journal, Volume XI (April 1860); The Photographic News, Volume IV (Oct. 23, 1860); Meyer, The Roots of American Industrialization; Wood County Reporter, Grand Rapids, Wis., Sept. 1, 1860; The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Ky., Aug. 24, 1860; New England Farmer, Boston, Sept. 15, 1860; Hartford Courant, Hartford, Conn., Sept. 3, 1860, and May 17, 1913; Perrysburg Journal, Perrysburg, Ohio, Aug. 9, 1860; Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 11, 1860; Nashville Union and Tennessean, Nashville, Tenn., Aug. 16, 1860; Harper’s Weekly, May 18, Aug. 3 and 10, 1861; Wilson, Trow’s New York City Directory, for the Year Ending May 1, 1862; Facebook Instant Messenger exchange with Wes Cowan, Sept. 9, 2022; Szabo, “My Heart Bleeds to Tell It”: Women, Domesticity and the American Ideal in Mary Anne Sadlier’s “Romance of Irish Immigration,” University of Virginia (1996); The New York Times, Aug. 29, 1861; New-York Tribune, Sept. 17, 1861; Storrs, The “Twentieth Connecticut”; email exchanges with Rachel K. Wetzel, Senior Photographic Conservator, Library of Congress, and photographic historian Dr. Jeremy Rowe, Oct. 5-11, 2022.

Ronald S. Coddington is the Editor and Publisher of MI.

Nicholas Penachio is part of a well-known East Coast Civil War collector family. His interests and many years of collecting have made him a leading authority in identified Civil War items. This article was the result of buying an Abbottype of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans in 2015. At this time, nearly 150 different Abbottypes have been identified by the author.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.