By Ronald S. Coddington, featuring an image from the Mike Werner Collection

Women packed into the Church of the Puritans in New York City on the morning of May 14, 1863, for an historic convention. A glimpse across the hall revealed familiar faces. On the rostrum, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Ernestine L. Rose and other leaders of the women’s rights and abolitionist movements settled in for the day’s events. A group of progressive Quakers filed into the first row of pews and chatted. The benches behind them filled with other movers and shakers, some well known and others less so, who had traveled far and wide to unite under the banner of a new organization.

At 10 o’clock, Susan B. Anthony called the meeting to order. Standing on the stage, her voice filled the void created by the hush that had descended across the room. “In this crisis of our Country’s destiny, it is the duty of every citizen to consider the peculiar blessings of a republican form of government and decide what sacrifices of wealth and life are demanded for its defense and preservation,” noted the 43-year-old veteran social reformer.

With these words, Anthony ushered in the Woman’s National Loyal League.

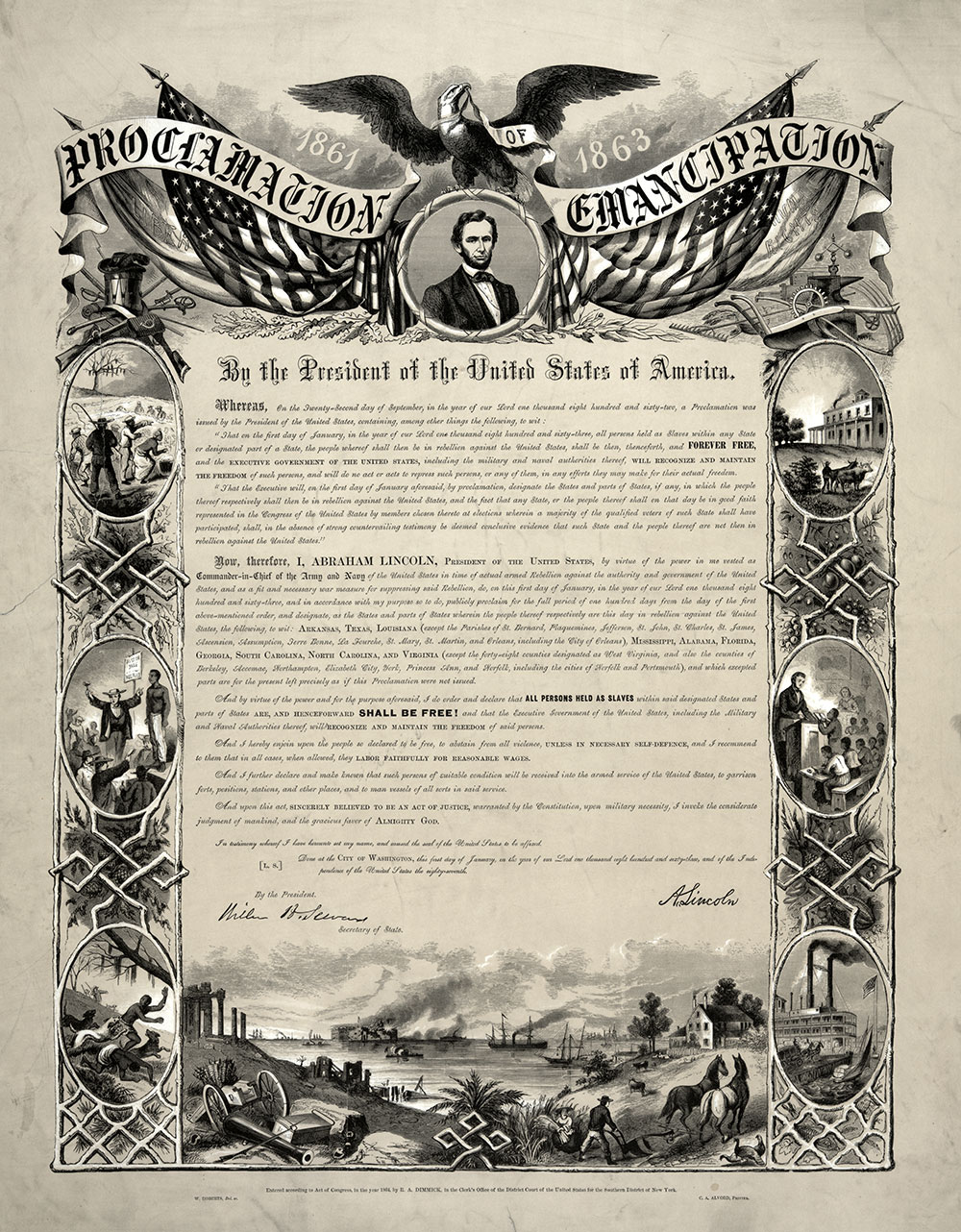

The League formed at a precarious moment. Two years into the Civil War, the future of the Constitution appeared to be in free fall. The national armies faced stubborn resistance from their counterparts in the states in rebellion; military successes were few and far between. The recent presidential proclamation of a limited abolition of slavery broadened the war’s aims from a struggle to preserve the Union to a moral fight for freedom and liberty for all. Universal equality, once a radical fringe concept, flowed into the mainstream of thought and rippled across the land.

In rural and urban communities across the Northern states, the debate about free versus slave labor moved from progressive parlors into main streets. Native born and immigrant men confronted the impact of wealth accumulated directly and indirectly on the backs of enslaved people. Women, second-class citizens since the birth of the nation, worked tirelessly with little fanfare and less appreciation to support the troops. These same women also fought a running battle of perceptions with Northern men who accused them as lacking patriotism compared to Southern mothers, wives and daughters.

Fears that the great cultural disruption might tear apart and forever destroy the social fabric that blanketed the homeland were well founded. Doomsayers foretold the end of the federal government, and with it the death of democracy.

Optimists, including Anthony and Stanton, saw an opportunity to advance their agenda by leveraging the power of patriotic, war supporting women. But there was a problem: How to convert a critical mass of these indefatigable individuals from bandage-makers, caregivers, and local fundraisers to political activists.

“They could not see that the best service they could render the army was to suppress the Rebellion, and that the best way to accomplish that was to transform the slaves into soldiers,” observed Stanton in her postwar reminiscences.

Anthony and Stanton investigated the problem in early 1863. They consulted with other progressive minds, including New-York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley, Gov. John A. Andrew of Massachusetts, and reformers William Lloyd Garrison and Robert Dale Owen. The two women concluded their deliberations with a decision to establish the Woman’s National Loyal League.

In the middle of April 1863, Stanton issued a call to meet on May 14, noting, “At this hour, the best word and work of every man and woman are imperatively demanded. To man, by common consent, is assigned the forum, camp, and field. What is woman’s legitimate work, and how she may best accomplish it, is worthy our earnest counsel, one with another.” Newspapers spread the word, directing queries to Anthony.

Between this call to action and the May 14 meeting, Bobby Lee and his rebel army trounced Fighting Joe Hooker’s U.S. forces at Chancellorsville, adding another loss to the long string of defeats in the Eastern theater. In the West, Ulysses S. Grant’s spring campaign renewed efforts to capture the Mississippi River fortress city of Vicksburg. Modest early gains provided a glimmer of distant victory.

Meanwhile, plans materialized for the Loyal League convention. Though the exact number of attendees is unclear, it is easy to imagine hundreds of them travelled to New York City for the event. Attendees included the two women pictured here. Though their identities are currently lost in time, the Stars and Stripes, ribbon and striped belt leave no doubt of their patriotism. Their linked arms symbolize unity and solidarity of purpose in the attainment of common goals. An inscription confirms their attendance on May 14.

The convention they attended consisted of two sessions. The first occurred inside the Congregational Church of the Puritans, a gleaming white gothic edifice dedicated in 1847 by its pastor, Dr. George B. Cheever. A fervent abolitionist, he used his pulpit and influence to sermonize on slavery as a sin against God.

The day before Stanton and Anthony convened their meeting, Cheever’s church hosted a business meeting of William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society.

After Anthony opened the meeting with a stirring appeal, she nominated prominent women’s rights activist Lucy Stone as president of the Convention. Stone accepted, and announced a slate of Convention officers.

Stanton, her frosted hair and rounded figure making her look older than her 47 years, rose to deliver a few remarks. In a clear and perfectly intoned voice, she reminded the assemblage of the power of women. She touched on themes of justice and mercy, and challenged all to do more “than to stand silent spectators of the awful tragedy passing before them.” Stanton stated, “It was woman’s care to watch the sick and dying, in camp and hospital, to light up the dark valley of the shadow of death as the fair-haired boys passed through, in the thought that in their suffering they foresaw the birth of universal liberty.”

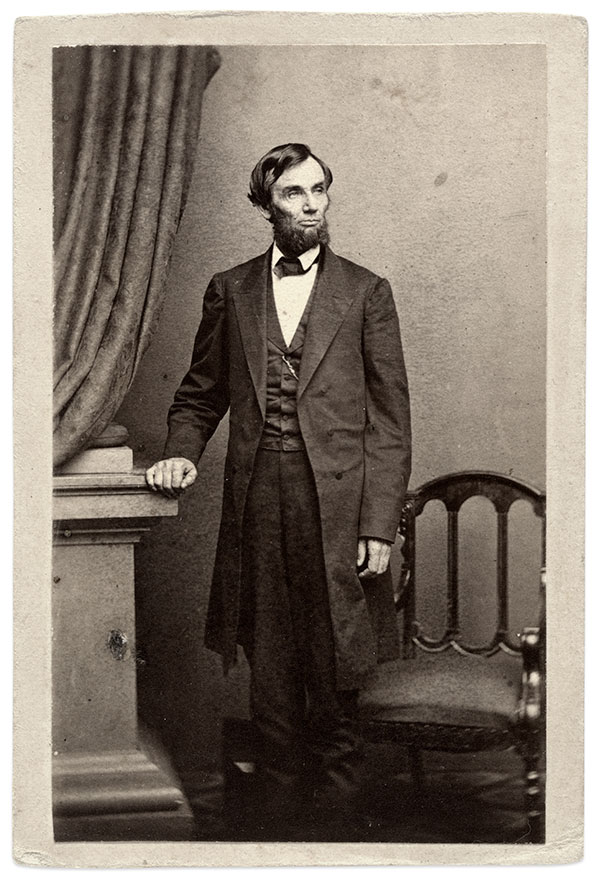

There were moments of levity as Stanton poked at the establishment, drawing laughter and applause from the crowd. At one point, a reporter noted, “Speaking of the Presidency of the United States now being filled by a rail splitter, she gave expression to the wish that he had as much skill in cutting down rebels as he was said to have had in cutting down trees.”

Upon the conclusion of Stanton’s address, more welcome speeches followed. Anthony then read a series of prepared resolutions. Seven in number, they recognized the inalienable right of self-government, supported the extension of the Emancipation Proclamation to include all enslaved people, called for equal rights for people of color and women, and pledged that women will sacrifice blood and treasure for the principles of freedom.

These resolutions were effectively a bill of human rights.

A short break followed, during which the popular music group Hutchinson family singers performed “The Contraband Song.” Afterwards, the floor opened for discussion and debate of the resolutions. One of the women who spoke, a Mrs. Chalkstone of California, issued a sober warning in halting English that the emancipation of Jews across Europe had unfolded over 18 centuries and had yet to be achieved, despite a recent failed social revolution in her native Germany.

The lion’s share of the debate revolved around a single resolution, however, the fifth, which linked the fortunes of people of color and women: “The property, the liberty, and the lives of all slaves, all citizens of African descent, and all women, are placed at the mercy of a legislation on which they are not represented. There can never be true peace in this Republic until the civil and political equality of every subject of the Government shall be practically established.”

Opponents to the resolution, led by Elizabeth Orpha Samspon Hoyt of Wisconsin, a newly appointed vice president, argued it went too far in pushing a radical agenda of the women’s rights movement. Supporters, including Ernestine L. Rose, a Polish Jew and naturalized American, and South Carolina abolitionist Angelina Grimké Weld, welcomed the combination of Blacks and women in the fight for equality.

The debate continued and the lines of division hardened as attendees staked out positions in context to the larger women’s movement. The momentum began to shift with the testimony of a Mrs. Spence, who sought to refocus the group on shared values and unity of action. “I don’t claim to be a Northerner or a Southerner; but I claim to be a human being, and to belong to the human family. I belong to no sect or creed of politics or religion; I stand as an individual, defending the rights of every one as far as I can see them.”

In the end, the fifth resolution gained a majority of the vote and passed. The other resolutions received unanimous consent.

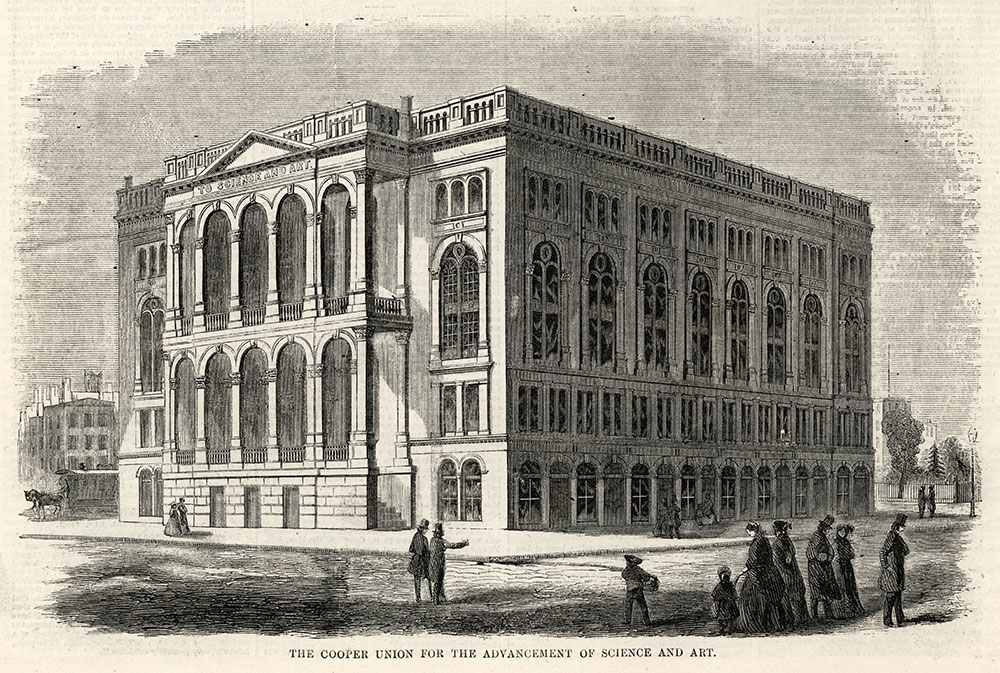

The second session began at 8 o’clock that evening at the Great Hall of the Cooper Union. Peter Cooper, a progressive-minded industrialist and philanthropist, had founded the college four years earlier as a place for people of all demographic and economic stripes to get a quality education. The Great Hall with a capacity of 900 had hosted numerous dignitaries, including President Lincoln’s 1860 campaign visit.

On this night, the crowd was considerably smaller than the morning session according to a news report. Blame fell on rain that rolled into town and an entry fee that may have turned some attendees away.

Those who braved the weather and paid the charge still buzzed from the scintillating debate and discussion at the morning’s Convention. Empowered attendees pledged to support the government in its war for freedom and resolved to establish the Loyal League. They nominated Stanton president and Anthony secretary. Addresses by Anthony, Rev. Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first woman ordained as a Protestant minister in America, and Rose inspired all.

Anthony read an address to her new Loyal League sisters that had been written for an audience of one: Abraham Lincoln. “You are the first President ever borne on the shoulders of freedom into the position you now fill. Your predecessors owed their elevation to the slave oligarchy, and in serving slavery they did but obey their masters. In your election, Northern freemen threw off the yoke. And with you rests the responsibility that our necks shall never bow again.” She continued, “‘The Union as it was’ — a compromise between barbarism and civilization — can never be restored, for the opposing principles of freedom and slavery cannot exist together.”

Anthony encouraged Lincoln to expand and codify the Emancipation Proclamation. “The nation waits for you to say that there is no power under our declaration of rights, nor under any laws, human or divine, by which free men can be made slaves; and therefore your pledge to the slaves is irrevocable, and shall be redeemed.”

The following afternoon, at the Church of the Puritans, the women gathered again to flesh out additional details of the League, including a pledge, platform and the election of an executive committee. Another address, prepared by Angelina Grimké Weld, expressed gratitude to citizen soldiers. She reminded them that the war “began in 1620, when the Mayflower landed our fathers on Plymouth Rock, and the first slave-ship landed its human cargo in Virginia. Then, for the first time, liberty and slavery stood face to face on this continent.”

Grimké Weld continued: “This war is not, as the South falsely pretends, a war of races, nor of sections, not of political parties, but a war of Principles; a war upon the working classes, whether white or black; a war against Man, the world over. In this war, the black man was the fist victim; the working-man of whatever color the next; and now all who contend for the rights of labor, for free speech, free schools, free suffrage, and a free government, securing to all life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are driven to do battle in defense of these or to fall with them, victims of the same violence that for two centuries had held the black man a prisoner of war.”

The meeting soon closed, and over the next six weeks the leadership of the League finalized the work of the Convention. Thus began the real work of the organization. Stanton, Anthony and other members — 5,000 strong — lobbied Congress through a mammoth petition campaign that contributed to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery. In December 1865, the amendment became law after enough states ratified it.

The Woman’s National Loyal League left a legacy of political activism that influenced future generations of women who successfully campaigned for suffrage and continue the fight for equality today. The two women pictured here with the flag participated in the birth of this transformative organization. It is easy to imagine that they went on to preserve, protect and defend the rights of women at home and human rights across the globe.

References: Stanton, Anthony, and Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. II; Proceedings of the Meeting of the Loyal Women of the Republic, Held in New York, May 14, 1863; New York Herald, May 15, 1863; Cheever, God Against Slavery and the Freedom and Duty of the Pulpit to Rebuke It, as a Sin Against God; The Daily Evening Press, Lancaster, Pa., April 17, 1863; New York Daily Herald, May 14 and 15, 1863; Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1863; Stanton, Eighty Years and More (1815-1897): Reminiscences of Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Gordon, The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.