By Ron Field

Some of the original European hussars served as quasi-military auxiliaries raised in 1458 by King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary to fight against the Turks. The hussars developed into the elite light cavalry of the Austrian Empire. With the absence of such forces in the regular armies of Central and Western Europe, the name and character of the hussars spread across the continent. Traditionally regarded as arrogant and stubborn, they were, for the most part, men of slight stature mounted on small, lively horses of about 15 hands high. The hussars quickly gained a reputation as relentless foragers, and unexcelled when pursuing a routed enemy.

The term hussar likely derives from the Old Serbian husar, meaning brigand, pirate, or freebooter. Like pirates, hussar units often wore the Totenkopf, or death’s head “skull and cross bones” device on their caps. By the 18th century, most European hussars also wore a short, fur-trimmed riding jacket, called a pelisse or dolman, which was usually draped over the left shoulder to ward off saber blows. Headgear consisted of a brimless fur cap (originally made from a wolf pelt) called a colpack or busby, with a cloth crown, which hung bag-like down the side. By the beginning of the 19th century, the fashion had reached the U.S., being introduced particularly by European immigrants to the cities on the eastern seaboard.

The hussar influence in antebellum New York State militias

In New York City, six independent cavalry companies composed almost entirely of German residents were organized into the 3rd Regiment (Hussars), New York State Militia, by Samuel Brooke Postley, president of the Hoffman Steam Coal Company, of Allegany, in 1847. On May 5, 1855, the New York Daily Herald reported on the Spring Parade of this regiment, which had expanded to 10 troops, and highlighted the difficulty involved in training mounted militia in the metropolis, stating, “The Hussars made a brilliant appearance as they swept down Broadway, though some of the horses … looked as though a trough of good oats and hay would have done them no harm; as a general thing, however, they were a fine-looking body of horse. It is, of course, impossible to expect good drilling in a mounted regiment in this city, as the facilities for the manoeuvring of horses in a large body are very few; but as far as we could judge, the Hussars made a very creditable parade, and did their commanding officer no little honor.”

The regiment adopted new uniforms in 1854 that did away with some of the variation in dress among troops. On September 12, it paraded in hussar style uniforms—minus the pelisse riding jacket described by the New York Times two days later as a “useless appendage.”

After the Spring Parade in 1855, the May 5 edition of the New York Daily Herald described the uniforms as “blue, edged with yellow trimmings, and the usual hussar caps.” By this time, the regiment also included a company wearing the “Brunswick hussar uniform, black trimmed with white.”

Another hussar-influenced organization was Troop C of the 30th New York State Militia. On July 23, 1861, volunteers from other companies in the regiment, amounting to 100 men, left the state under the command of Capt. George W. Sauer. After three months’ service, it mustered out at New York City on Nov. 2, 1861.

The hussar style also touched the 70th New York State Militia. In June 1855, Col. Samuel Graham paraded the regiment. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described it as being “attired in blue instead of a mixture of colors, as heretofore.” Comprised of all the mounted companies of the Fifth Brigade of Militia, this regiment was composed of three cavalry companies and two mounted artillery companies, the former consisting of the Ringgold Horse Guards, Kings County Troop and Washington Horse Guards. Based on photographic evidence, one of these companies wore a hussar-style uniform minus the pelisse.

Other notable pre-war Hussar militias

Capt. Philip Becker formed a troop of “Black Hussars” among the German citizens of Philadelphia in 1857.

On May 30, 1858, the troop escorted the hearse during the funeral of a Mexican War hero, Brig. Gen. Persifer F. Smith. An eyewitness reported, “Their uniform is pure black, trappings of the same hue, and are mounted on black and dark colored powerfully-built horses, the men all of the mightiest stature, and their countenances, what portion can be seen through the heavy overhanging hat or hood, and bared from their fierce moustaches and long beards, appears like grim death itself, in contrast with their uniform. To complete the picture, there is a silver skull and cross bones on the front of their hats, shining like a meteor of destruction, as their motto implies—to ‘neither crave or grant mercy.’”

On April 16, 1861, the Black Hussars formed part of the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, of the Pennsylvania Volunteers. They again performed escort duty when Maj. Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame visited the city in May 1861. That same month, Capt. Becker applied to the City Council for funds to mount his 75-man company, but help was not forthcoming. By mid-June 1861, the hussars numbered 300 men according to a list compiled and published by the New York Herald. Becker disbanded the unit about this time, and went on to volunteer as lieutenant colonel of the “Cameron Dragoons,” which enlisted for three years as the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry, or 65th Pennsylvania.

In the Far West, a company of Black Hussars was formed in San Francisco in October 1857 with Capt. William S. Alton in command. During the Independence Day Parade in 1859, the San Francisco Bulletin reported that they wore “black costumes and black horses, black caps and silver trimmings.” A report in the Sacramento Daily Union added, “They were preceded by two mounted trumpeters, clad in black pants and grey roundabouts, who sidled half about in their seats at every street turn, and repeated, in bugle style, the notes designating the required movement, until the line had been fairly directed to the proper front.”

In June 1861, this company was organized into the 1st Regiment of Infantry, 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, of the California Volunteer Militia. Re-organizing under Capt. Charles H. Seymour in January 1862 as the San Francisco Hussars, they adopted a new uniform, which reported to be “very showy” and presumably not black. From 1863 through 1866, they formed part of the 1st Cavalry Battalion, 2nd Brigade, California Militia.

In Detroit, a company called the Detroit Hussars or Michigan Hussars commanded by Capt. Angelo Paldi existed by July 1859. Three months later, on October 27, the Detroit Free Press reported, “The Hussars, a cavalry company parading twenty-six members on horseback, and equipped in the very showy and attractive uniform worn by that species of soldiery in the European service.”

On May 1, 1861, the hussars, now commanded by Capt. Horace S. Roberts, became Company F of the 1st Michigan Infantry. Two weeks later, it arrived at Washington, D.C., and formed part of the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, of the army of Brig. Gen. Irwin McDowell. The Michiganders fought at the First Battle of Bull Run, where regimental commander Col. Orlando Wilcox led several charges before being wounded and captured. The hussars sustained one officer and one private killed, plus an unspecified number of wounded and/or missing.

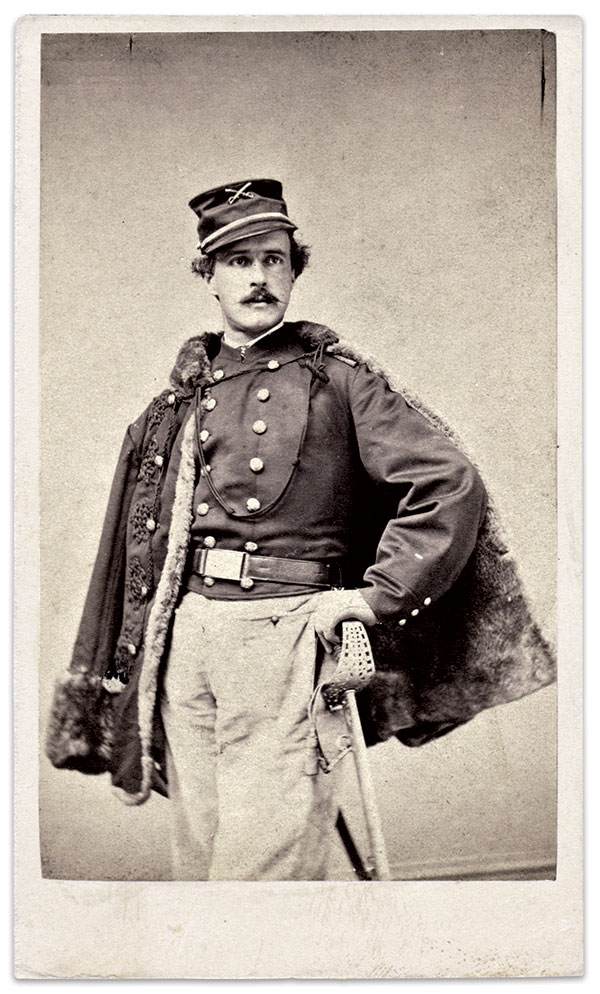

Hussars raised in St. Louis after the war began

Two hussar units were raised among the German community of Union supporters in St. Louis in 1861. Named for Jessie Benton Frémont, the influential wife of former Republican presidential candidate Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, the Frémont Hussars, also known as the “First Regiment Western Cavalry,” were composed of eight mounted companies. The commander of the troopers, Col. George E. Waring, Jr., previously served as an officer in the 39th New York Infantry, or the Garibaldi Guard. Although the men likely received standard issue U.S. cavalry clothing and equipment, Waring and several officers under his command were photographed with hussar-style fur-lined pelisses over their shoulders or worn as coats.

Also in the Midwest, the Benton Hussars were recruited and served as a bodyguard for Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel. The colonel in command, Christian Casselmann, died from disease in November 1861. According to a report in the Jan. 24, 1862, edition of the New York Tribune, the unit was “instructed in horsemanship and sword exercise by a Prussian officer, after the European fashion.”

On Nov. 13, 1861, the Grant County Herald of Lancaster, Wis., reported the men had been “promised their uniforms one hundred times, and expect one thousand more promises.” At this time, they were stationed at Camp Garibaldi near St. Louis.

The Frémont and Benton Hussars fought in the Union victory at Pea Ridge, Ark., on March 7-8, 1862. The hussars served in Hungarian-born Brig. Gen. Alexander Asboth’s 2nd Division in the Army of the Southwest, led by Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis. According to the Chicago Tribune on March 22, 1862, the Frémont Hussars lost 15 killed, wounded, and missing, and the Benton Hussars suffered 16 casualties.

Later in 1862, military authorities consolidated the Benton Hussars with the Holland Horse to form the 5th Missouri Cavalry. Another consolidation created the 4th Missouri Cavalry, a regiment of hussars in name only.

Another company of hussars came into existence in Missouri in early 1864. In St. Louis, one of the recruiters for the 12th Missouri Cavalry, Lt. Harry M. Sherman, received authorization to organize Sherman’s Hussars. The recruits were to be clothed in “tasteful and attractive” uniforms, reported the Daily Missouri Republican on January 10. During the following month, regimental commander Lt. Col. Oliver Wells attempted to raise a full battalion of light hussars to be attached to the 12th. Wells’ efforts appear to have failed.

Sherman succeeded in raising his hussars, and they were incorporated into the 12th as Company A. The men served in Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi from 1864-65. During this period, any semblance of its uniform was doubtless abandoned.

Hooker’s Hussars

Major Gen. Joseph Hooker, remembered for his introduction of corps badges and flags for the Army of the Potomac, attempted to supply his orderlies with hussar uniforms trimmed with green braid in 1863. Ordered from the clothing depot in New York City, some of these uniforms were shipped via the steamer Patroon. On April 2, 1863, the vessel wrecked on its way to Washington. The uniforms were salvaged and dried out, and some may have been issued to orderlies at Hooker’s headquarters by the end of the month—just before the Battle of Chancellorsville.

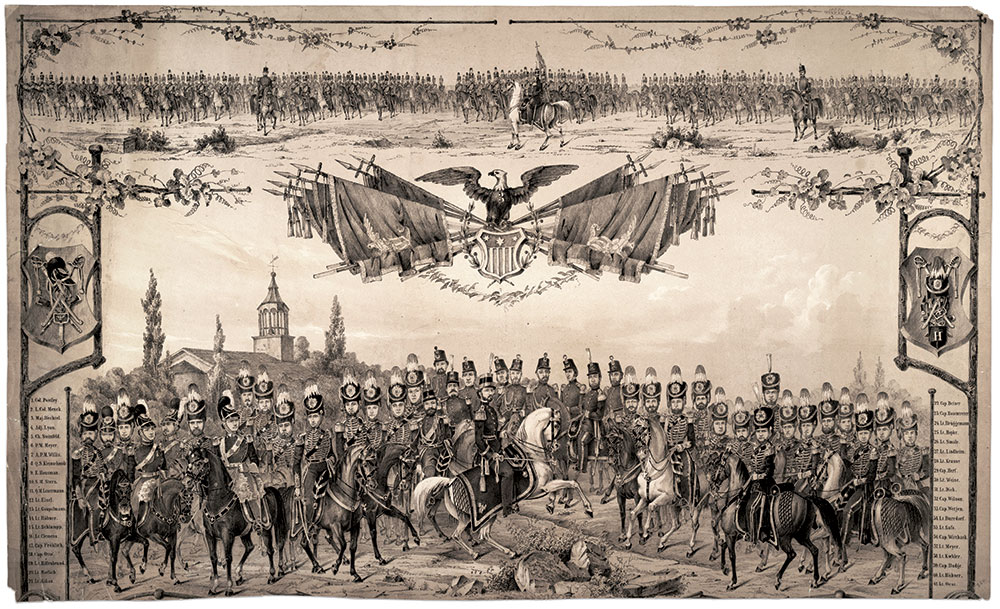

The only hussar regiment with an extensive fighting record: 3rd New Jersey Cavalry

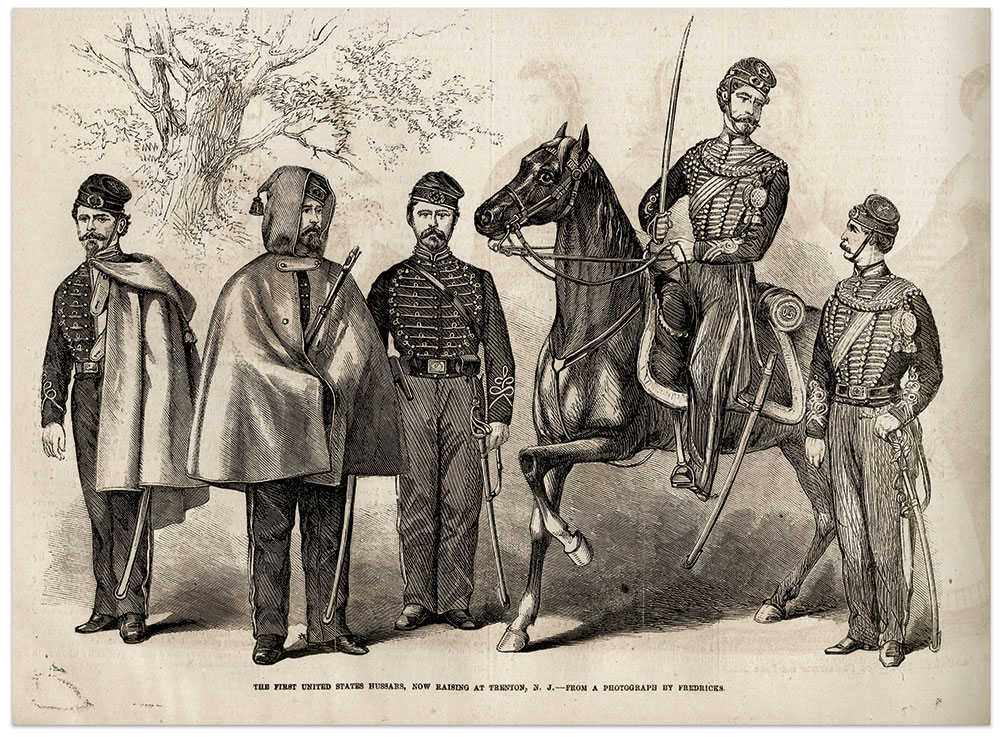

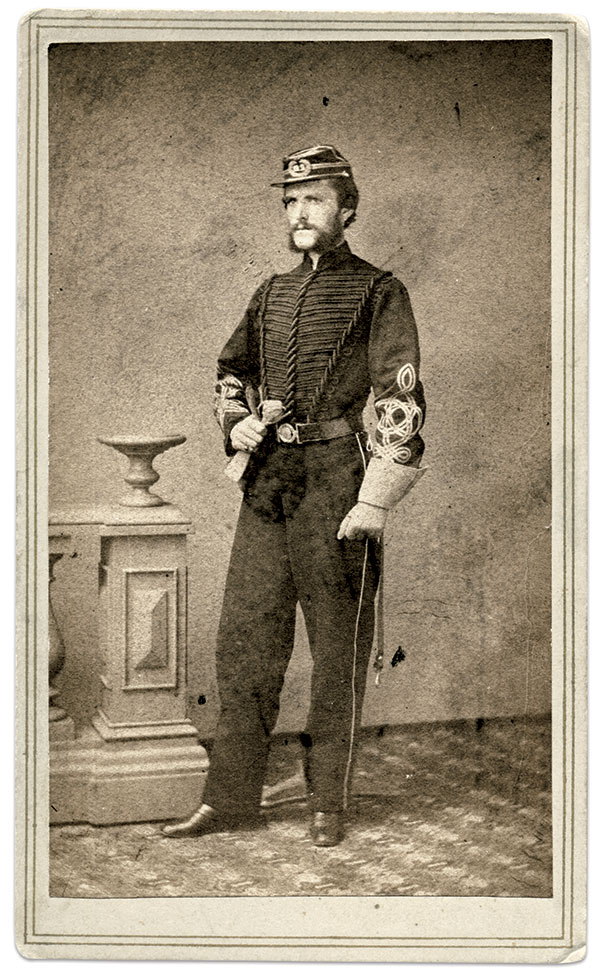

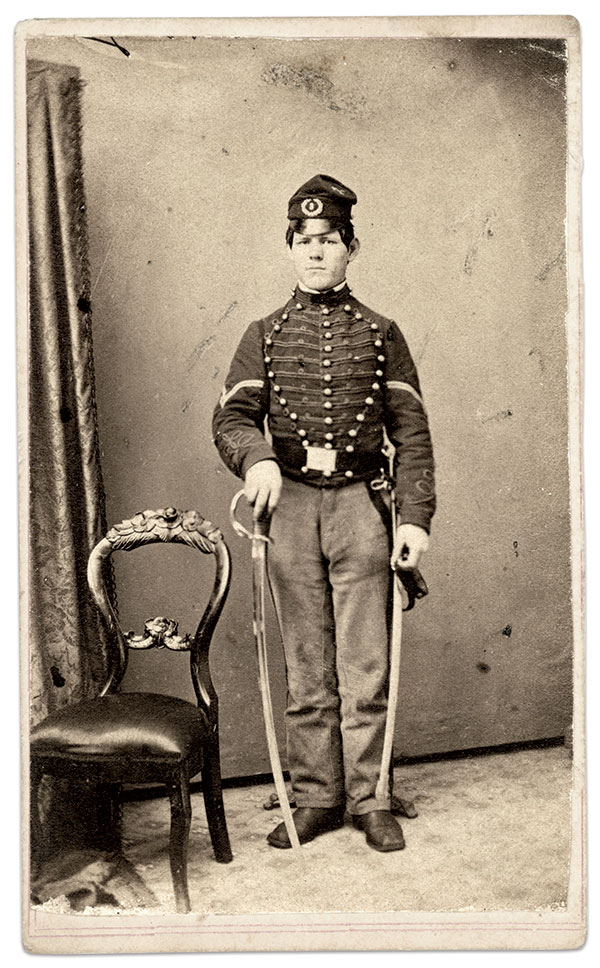

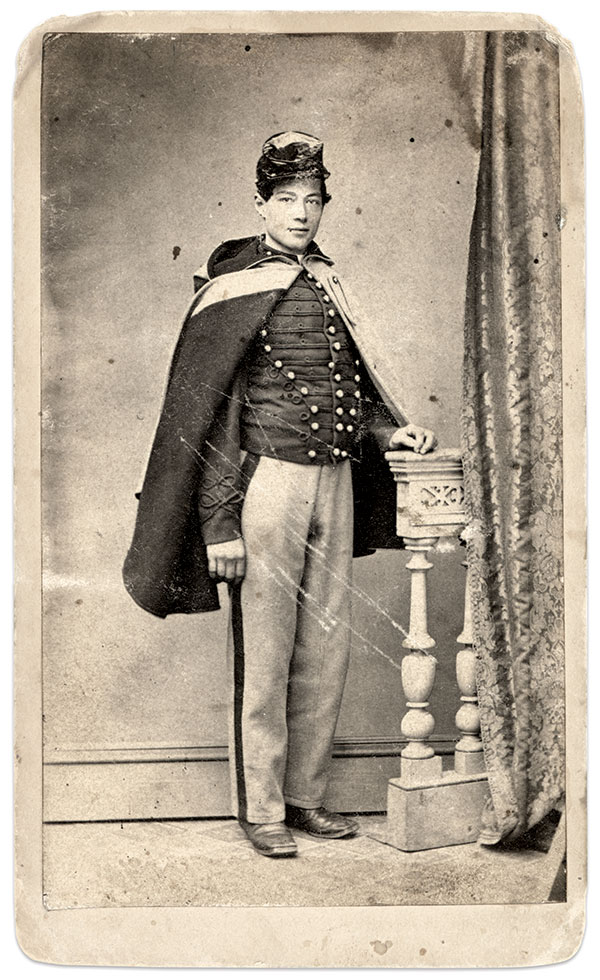

Only one full-strength hussar regiment experienced extensive Civil War service: the 3rd New Jersey Cavalry, also designated the 1st Regiment U.S. Hussars. Raised during the first quarter of 1864 in response to President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 new volunteers, Col. Andrew J. Morrison originally commanded the regiment. A soldier of fortune who claimed service with Italian nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi, Morrison designed the hussar uniforms worn by his regiment. He insisted the men be armed only with sabers, although some were issued revolvers.

Assigned to Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s 9th Corps, the Jerseymen’s showy uniforms attracted generals who detached them for orderly, courier and escort duty. Other soldiers in the 9th Corps ridiculed the hussar jackets overloaded with yellow braid. An enlisted man in the 16th Illinois Cavalry, John McElroy, noted that the hussars were derided as “daffodil cavaliers” and dubbed the “Butterflies.”

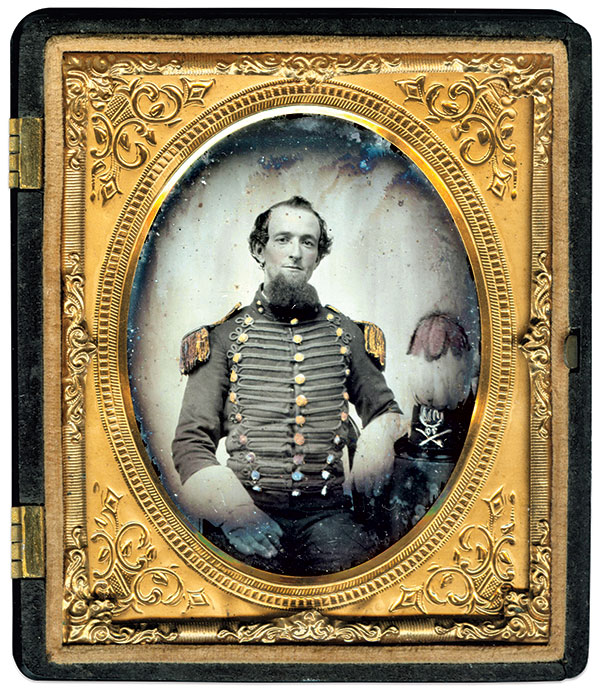

Rick Carlile Collection.

By late August 1864, the reputation of the hussars shifted towards more positive. Morrison was replaced by the more efficient command of Lt. Col. William P. Robeson, Jr., and moved to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley with the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac in the Shenandoah Valley. Here, the hussars proved themselves in the battles of Winchester and Cedar Creek, and later at Five Forks and Saylor’s Creek, which culminated in Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. After a final spell in the defenses of Washington, the hussars mustered out between May and August 1865. Overall casualties during its service included three officers and 47 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded, and two officers and 105 men who succumbed to disease.

A description of the uniform worn by the 3rd accompanied by an engraving based on a photograph credited to Charles D. Fredericks of New York City appeared in the Jan. 9, 1864, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The uniform was based on “that of the Austrian hussars. The pantaloon is the usual cavalry one, with a yellow stripe; and the jacket is trimmed with yellow cord. The baldrick and agrete are worn over the shoulder and across the breast. Instead of an overcoat, they wear a talma, with a tassel over the left shoulder. The cap is very neat and comfortable.”

Non-commissioned officers wore regulation chevrons in yellow braid on their sleeves. As the yellow trouser seam stripe worn by privates was the usual distinction for a cavalry sergeant, an orange cord on each side of their seam stripes further distinguished non-commissioned officers.

The hussars’ headgear consisted of an unusual form of “pillbox” cap, which differed from the cylindrical European version by having a soft top. This created the general effect of an American forage cap without a visor, although some men were photographed wearing versions complete with a visor. The top and bottom edges of the cap band were trimmed with yellow cord, within which was the numeral “3” within a wreath. On top of the cap, some enlisted men wore brass company letters above brass crossed saber cavalry insignia, facing sideways.

In addition to its regulation blue silk cavalry standard, the hussars carried a dark blue standard fringed in gold, simply showing a large brown and black butterfly; its wings edged in white. What had been intended as an insult became a title to be proud of for the Jerseymen who carried the hussar-tradition on to the end of the Civil War.

Special thanks to Jérôme Lantz, Dennis Hood, Jeff Patrick, Jim Brown, Rick Carlile, John Kuhl, Ron Maness, Nicholas Ciotola, curator of Cultural History, New Jersey State Museum; Paula (Andras) Bisson, registrar, Cultural History, New Jersey State Museum; and Peter Harrington, curator at the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University in Providence, R.I., for kind assistance with the preparation of this article.

References: Risley, Clyde A. and Todd, Frederick P. “3rd New Jersey Cavalry Regiment, 1864-1865 (1st Regiment, U.S. Hussars),” Military Collector & Historian, Vol. IX, No. 1 (Summer, 1957); Sickles, John. “American Hussars,” Military Images, Vol. 16, No. 4 (January-February 1995); McAfee, Michael J. “3rd Regiment New Jersey Volunteer Cavalry, 1864-65 (1st U.S. Hussar Regiment): ‘A Horse to Ride and a Sword to Wield,’” Military Images, Vol. 21, No. 4 (January-February 2000; Elting, John R., and Sturke, Roger D. “Hooker’s Hussars,” Military Collector & Historian, Vol. XXXIX, No. 4 (Winter 1987); Lubrecht, Peter T., New Jersey Butterfly Boys in the Civil War: The Hussars of the Union Army; McElroy, John, Andersonville: The Story of Rebel Military Prisons; Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 2; various newspapers.

Ron Field is a Senior Editor of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.