By Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel

Civil War veterans acknowledged their military service as the most significant experience of their lives. They filled uncounted albums with photographs of their pards to remember friendships forged against a backdrop of war.

Time has taken many of the albums from us. Water, fire and gradual decay have claimed some. Others have fallen victim to apathetic families who lost touch with their Civil War ancestors. Many have been discarded, or broken up, the precious images inside distributed to family members or sold to dealers and collectors.

Some survived intact, including this worn leather album small enough to slide into a shirt pocket. It holds just ten photographs.

This small memento holds one Union soldier’s world: his regiment’s flag, two hospital stewards, three noncommissioned officers, a soldier nurse from the regimental hospital, and a charismatic colonel who became a larger than life figure with a name to match—The Perfect Tiger.

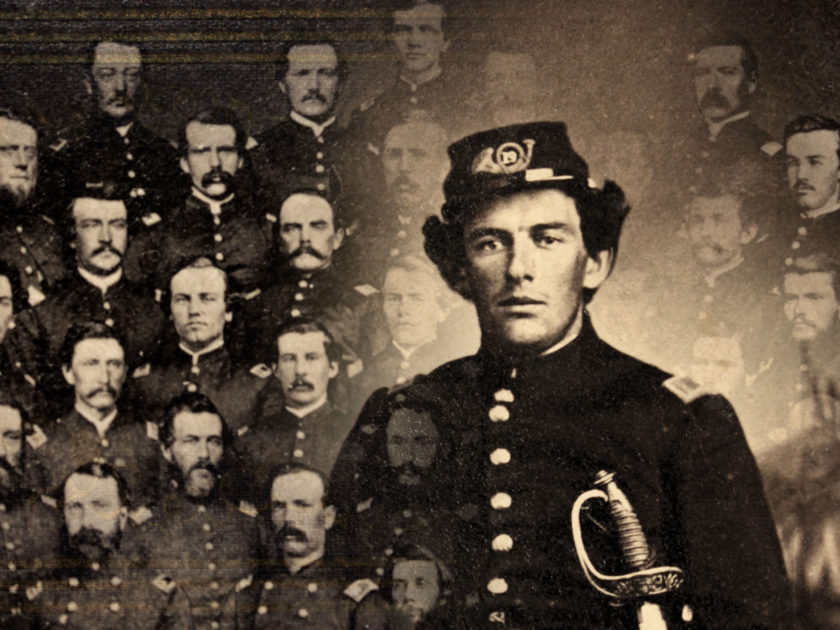

The image set into the inside of the album’s first page is likely the individual who collected the cartes de visite, inscribed the backs of the mounts, determined the order, and inserted them into the album sleeves. The photographs he selected reveal who and what were most important to him.

He is 1st Lt. Charles Julius Deming, who served for less than a year, from August 1862 to July 1863, as adjutant of the 19th Connecticut Infantry. An unusual unit, the 19th formed as a county regiment. Drawn from the hill towns of Litchfield County, its members were friends, cousins, brothers, schoolmates, and neighbors, creating a regiment of men strongly bound to each other.

“Charley,” as the men pictured here familiarly knew him, spent much of his military service in the hospital or on furlough. Mumps and measles had attacked the men of the 19th, with Adjutant Deming falling victim to the former. Mumps carried more danger for grown-ups than children; the virus could and did kill adults. Charley did not recover quickly. In February of 1863, he lay in the hospital; two months later, he was still not fit for duty. A soldier who knew him wrote, “If possible [he] will get a furlough to go home to recruit his health, which is very poor.”

Deming left the army before his regiment’s defining moments, including its conversion to the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, the adrenaline-fueled advance toward the entrenched enemy at Cold Harbor that ended in death and destruction, and operations in the Shenandoah Valley.

Despite his limited service, Deming’s album stands as proof of his enduring bond with fellow soldiers who had the greatest impact on him. The photographs of medical staff, uncommon in soldiers’ albums, suggest that these men are to be counted among his heroes. The inclusion of these caregivers indicates Deming valued the many dimensions of soldiering. Some men leapt over stone walls and raced through a leaden hail to capture battle flags, while others cooled the foreheads of comrades shaking with fever.

The images of these medical men adjacent to the color bearer, colonel, a montage of staff officers, and Deming himself, provide a unique context. They can be appreciated as a group that tells the larger narrative of one man’s Civil War experience, or as single images, each with its own story.

Deming’s war story ended on a July day in 1863 when his resignation letter was read aloud at dress parade. “We have lost the best officer for adjutant that there was in the regiment,” lamented one soldier.

Deming returned to Connecticut, but his bond with the men remained unbroken. Seven months later, in early 1864, he visited the regiment in its winter quarters and reconnected with his former comrades, visiting tents and shaking hands. He left with an open offer to rejoin the staff, which he chose not to act on.

More than a century and a half later, the worn album stands as a testament to a soldier, a regiment and memories of a lifetime. Turning its pages conjures visions of the war seen through the lens of Deming’s experience. A viewer can easily imagine the men in these portraits alive if only for a fleeting moment: the laughter of pals, the odor of a crowded hospital, the commanding voice of a beloved colonel.

The album also reminds those of us who collect these artifacts of their importance to our American story. Keep your notes and information together with the images. And make sure to identify your own family photos, whether print or digital, for future generations to appreciate.

The images

Charley

First Lt. and Adjutant Charles Julius Deming (1838-1905): Born into a wealthy, prominent family in Litchfield, Deming was the grandson of Revolutionary War officer Julius Deming. In the fall of 1861, young Deming mustered into Connecticut’s 4th Infantry as a private. Weeks later, the regiment transformed into the 1st Heavy Artillery. In the summer of 1862, he left to join the 19th as adjutant and resigned in July 1863.

The Color Bearer

Thomas Fox (life dates unknown)Cpl. Thomas Fox poses with the state colors. A member of Company B, he joined the regiment in early 1864, about seven months after Deming’s departure, and mustered out in August 1865. He wears a standard flag bearer’s belt, and attached to his coat an apparent patriotic or regimental ribbon.

The Physician’s Son

Sgt. Matthew Henry Huxley (1841-1864)Huxley fell sick and died of consumption in the regimental hospital. He was 23. His father, Dr. A. Mack Huxley, had passed just three weeks earlier. Dr. Huxley had come south to care for his son, but a heart attack killed him instantly as he ate dinner.

The Non-Coms

The boyish James J. Averill (1843-1887), an 18-year-old Yale medical student, served as hospital steward. The job carried enormous responsibilities, as a steward supervised the entire hospital, managing its heating and ventilation, handling hospital finances, procuring its food and monitoring meal preparation, ensuring the availability of supplies and equipment, preparing patients’ medicines in the hospital dispensary, and assisting in surgeries. Averill, still a teenager, had other concerns as well—his mother had died when he was a child, and his father died of disease in 1863 while serving as chaplain for the 23rd Connecticut Regiment in Louisiana. At war’s end, Averill returned to his studies and graduated with his medical degree in 1866.

The boyish James J. Averill (1843-1887), an 18-year-old Yale medical student, served as hospital steward. The job carried enormous responsibilities, as a steward supervised the entire hospital, managing its heating and ventilation, handling hospital finances, procuring its food and monitoring meal preparation, ensuring the availability of supplies and equipment, preparing patients’ medicines in the hospital dispensary, and assisting in surgeries. Averill, still a teenager, had other concerns as well—his mother had died when he was a child, and his father died of disease in 1863 while serving as chaplain for the 23rd Connecticut Regiment in Louisiana. At war’s end, Averill returned to his studies and graduated with his medical degree in 1866.

First Lt. Edward Charles Huxley (1843-1908), younger brother of Sgt. Matthew Huxley, entered the army as a private at age 18, and rapidly advanced to quartermaster sergeant, second lieutenant and first lieutenant. He eventually commanded Company L, composed entirely of recruits. As such, it did not have the same close-knit nature as the regiment’s earlier companies. Huxley and other company officers struggled to maintain morale as more than 90 of its number deserted.

First Lt. Edward Charles Huxley (1843-1908), younger brother of Sgt. Matthew Huxley, entered the army as a private at age 18, and rapidly advanced to quartermaster sergeant, second lieutenant and first lieutenant. He eventually commanded Company L, composed entirely of recruits. As such, it did not have the same close-knit nature as the regiment’s earlier companies. Huxley and other company officers struggled to maintain morale as more than 90 of its number deserted.

Dashing peacetime dentist 1st Lt. Franklin J. Candee (1838-1864) first served as commissary sergeant before he advanced to the officers’ ranks in early 1864. At the Battle of Winchester, Va., in September 1864, as the regiment lay in a hollow, waiting to go into action, “Candee merely raised himself from the ground on his elbow to look at his watch, but it was enough to bring his head in range of a sharpshooter’s ball, and he was instantly killed,” reported the regimental historian.

Dashing peacetime dentist 1st Lt. Franklin J. Candee (1838-1864) first served as commissary sergeant before he advanced to the officers’ ranks in early 1864. At the Battle of Winchester, Va., in September 1864, as the regiment lay in a hollow, waiting to go into action, “Candee merely raised himself from the ground on his elbow to look at his watch, but it was enough to bring his head in range of a sharpshooter’s ball, and he was instantly killed,” reported the regimental historian.

The officer who preceded Deming as adjutant, 1st Lt. Bushrod H. Camp (about 1835-1895), worked as a bookkeeper before the war. Wounded in the leg at the Battle of Cold Harbor, he left the regiment with a discharge in November 1864. He lived until age 60, dying in a soldiers’ home.

The officer who preceded Deming as adjutant, 1st Lt. Bushrod H. Camp (about 1835-1895), worked as a bookkeeper before the war. Wounded in the leg at the Battle of Cold Harbor, he left the regiment with a discharge in November 1864. He lived until age 60, dying in a soldiers’ home.

The Priest and Soldier

1st Lt. William Henry Lewis, Jr. (1842-1913) left his ministerial studies and enlisted in the regiment. Promoted to captain in February 1864, he suffered a wrist wound in the Battle of Winchester on Sept. 19, 1864, and was discharged for disability four months later. He went on to become an Episcopal minister. The engraved stone that marks his Evergreen Cemetery grave in Watertown, Conn., reads “Priest and Soldier.”

The Regimental Officers

Most of the regiment’s officers had plenty of patriotism but no prior military experience. Maj. Nathaniel Smith practiced law. Capt. James Rice taught school. Capt. Eli Sperry was a harness maker. The training they received in Connecticut only intensified in the South. Many found themselves overwhelmed, scrambling to memorize infantry commands such as “rally on the reserve” and “by the rear of column, left or right, into line, wheel.” Officers unable to master the complicated movements incurred the wrath of Lt. Col. Elisha Kellogg, who drilled the regiment without mercy.

The Assistant Hospital Steward

Asst. Hospital Steward Francis James Young (1843-1893). A classmate of Hospital Steward James J. Averill in Yale’s medical school, 19-year-old Francis Young acted as assistant hospital steward. He served in the regiment until the spring of 1864, when he transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps. After the war, he became a much loved and respected physician known for his “tender and warm-hearted spirit.” A colleague remembered that “his calm, sunny presence was like a tonic to the suffering.”

The Commander

Lt. Col. Elisha Strong Kellogg (1824-1864) The inclusion of Kellogg’s likeness in Deming’s album speaks to the respect of a subordinate for his commander. It also may have brought to mind many camp stories, including one that involved Deming and 1st Lt. Luman Wadhams. In July 1863, the two lieutenants joined in an alcohol-laced prank on a brother officer, Edward O. Peck, an unpopular captain who had just submitted his resignation.

“They found out that the captain had two gallons of whiskey,” explained a private who got wind of the prank. “They got Col. Kellogg to invite Capt. Peck up to his tent to have a little something to drink, so up comes the captain. The lieutenants slip into the captain’s back door, get the captain’s whiskey and cut for the colonel’s on the double quick and get there before the captain does. When the captain arrives he finds a crowd of brother officers to drink with. When the whiskey is all gone Capt. Peck sends down for his and finds it gone. The captain then smells a rat.”

The Nurse

Pvt. George W. Warren (1824-1904). A shoemaker in the village of New Hartford, the patriotic Warren left behind his wife and six children to enlist in the regiment in 1862. Old enough to be the father of some of the young men in the ranks, he became a nurse in the regimental hospital, where his countless duties included emptying bedpans; feeding, bathing and shaving patients; changing soiled sheets and clothing; administering medicines; cleaning up blood, urine, vomit and excrement; removing lice; keeping detailed notes on each patient; and dressing wounds. He regularly worked through the night. Listed in basic service records as a private, the inscription on the back of the mount of Warren’s carte identifies him as a nurse—and sheds new light on both his war experience and his connection to Charley and the others in the album.

Pvt. George W. Warren (1824-1904). A shoemaker in the village of New Hartford, the patriotic Warren left behind his wife and six children to enlist in the regiment in 1862. Old enough to be the father of some of the young men in the ranks, he became a nurse in the regimental hospital, where his countless duties included emptying bedpans; feeding, bathing and shaving patients; changing soiled sheets and clothing; administering medicines; cleaning up blood, urine, vomit and excrement; removing lice; keeping detailed notes on each patient; and dressing wounds. He regularly worked through the night. Listed in basic service records as a private, the inscription on the back of the mount of Warren’s carte identifies him as a nurse—and sheds new light on both his war experience and his connection to Charley and the others in the album.

The Alexandria Pard

Unidentified private. The brass attached to this soldier’s cap indicates he served in Company E of the regiment before its conversion from infantry to artillery in November 1863. He may have been one of Charley’s hospital mates. The stump and military backdrop behind him belonged to an Alexandria photographer who took the likenesses of many men from the 19th.

Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel co-authored Heroes for All Time: Connecticut Civil War Soldiers Tell Their Stories, a book featuring the images, artifacts and exploits of the citizen soldiers who made up the regiments from Connecticut who volunteered to save the Union and fought to set men free in the Civil War. They are both former players for the Panthers Hockey Club.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.