By Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel, with images and artifacts from the Buck Zaidel Collection

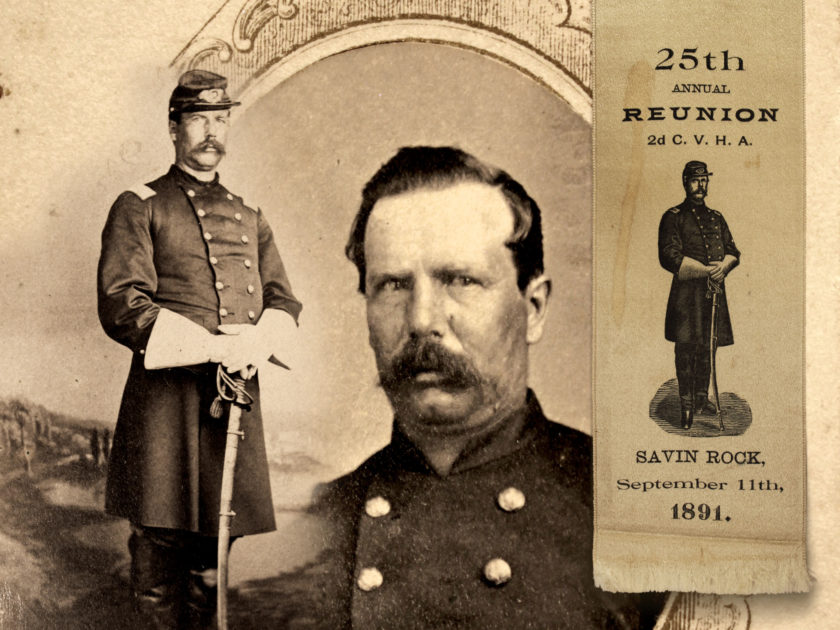

The 19th Connecticut Infantry’s first exposure to its new lieutenant colonel, Elisha Strong Kellogg, was memorable. It happened on an August day in 1862 inside the regiment’s home state camp at Litchfield, where green soldiers learned simple drills. “At about 11 AM we were all amazed at the sight of a tall and portly man equipped from his spurs to his shoulder straps,” wrote 1st Sgt. Michael Kelly of Company G in his diary.

Kelly noted that the men were drilling when Kellogg “came along & shouts like a tiger at a soldier named Burns who was smoking. ‘Take that pipe out of your mouth, Sir, and attend to your drill.’ Poor Burns trembled like a leaf.” Kelly added that Kellogg “caught the pipe & threw it with such [force] he never knew to this day where the pipe gone.”

Kellogg had arrived in camp straight from Virginia, where he had been a major in the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, and had participated in operations during the recent Peninsula Campaign. He brought much-needed military experience to the rookie regiment. He also brought leadership abilities that proved helpful as the colonel commanding, Leverett W. Wessells, suffered sickness much of the time.

The men rapidly discovered Kellogg’s intolerance. On another day during drill, 1st Sgt. Kelly described how Kellogg lit into four of his captains. One made a mistake in directing movements, and Kellogg told him to ask any of his privates for the proper way. Kellogg warned another captain that he’d have to drill his company “from hell to breakfast.” He hurled insults at two more captains, labelling one as an “Old Woman” and the other a “Turkey Cock.”

The lieutenant colonel was a paradox. “His nature was versatile, and full of contradictions; sometimes exhibiting the tenderest sensibilities and sometimes none at all,” recalled the regimental historian. “Now he would be in the hospital tent bending with streaming eyes over the victim of fever, … and an hour later would find him down at the guard house, prying open the jaws of a refractory soldier with a bayonet in order to insert a gag; or in anger drilling a battalion, for the fault of a single man, to the last point of endurance.”

In mid-September 1862, the 19th mustered into federal service and soon reported to Alexandria, Va., where it replaced a Massachusetts regiment patrolling the city. Kellogg, unhappy with unhealthy camp conditions, lobbied for change. In early 1863, the regiment moved to the nearby Defenses of Washington and occupied Fort Worth.

Still, inaction gnawed at Kellogg, who decided to make things lively for his troops. On one snowy day in February 1863, “We were marched outside the camp & formed in line of battle,” wrote Cpl. Frederick A. Lucas of Company C. “Then the Col. Ordered the Commandants of the Co to him & informed them that he was going to have a sham fight with snowballs for weapons.” Lucas continued, “The Col. Divided the Reg, the right wing against the left & about six rods apart. He took command of the right wing & the Major of the left. Before the fight commenced he told the boys to ‘show their spunk & keep their tempers & have no ill feelings or quarrelling.’ Then he gave the command ‘load at will, load’ and every man made his balls.”

The word “Fire!” came soon enough, Lucas noted, and then “came what a shower of snowballs & how the boys of the different Companies yelled. At the first fire, I received a black eye. … But on we went & the blood flowed freely from the smashed noses & cut mouths. Nearly every commissioned officer in the Reg received a bad bruise on the head or face.”

Even Kellogg got into the action, according to Lucas. He “rushed on, fought like a perfect tiger. When he saw a portion of his wing giving away and losing ground he would yell like a fiend, rushing into the thickest part of the fray. When he left the field his eyes were both badly hurt & nearly closed, & the blood run from nose & mouth. He retired laughing & well satisfied with the results.”

Fort Worth proved a pivotal assignment for officers and men. In its garrison, the regiment became familiar with artillery and began to drill by the rules of this branch of the service. Thus began a transition from infantry to artillery that lasted throughout the year at this and other forts along Washington’s defensive perimeter. Kellogg’s previous experience with the 1st Heavy Artillery came in handy.

In the midst of this change, Col. Wessells resigned due to illness. Kellogg advanced to colonel and commander in October 1863. A month later, he oversaw the official change in designation from the 19th Infantry to the 2nd Heavy Artillery.

Though prospects for future combat appeared dim, Kellogg did not let up for a minute on training, drilling and discipline. New recruits brought in to bolster the regiment’s manpower learned quickly that maneuvers had to be perfectly executed. Kellogg required the rank and file to wear white gloves at dress parade, and woe to the private whose gloves had a film of Virginia dust on them.

One officer mused about the charismatic Kellogg’s effect on the troops. “Notwithstanding his frequent ill treatment of officers and soldiers, he had a hold on their affections such as no other commander ever had, or could have,” noted the regimental history: “The men who were cursing him one day for the almost intolerable rigors of his discipline, would in twenty-four hours be throwing up their caps for him, or subscribing to buy him a new horse, or petitioning the Governor not to let him be jumped. The man who sat on a sharp-backed wooden horse in front of the guard house, would sometimes watch the motions of the Colonel on drill or parade, until he forgot the pain and disgrace of his punishment in admiration of the man who inflicted it.” Such respect and admiration may seem puzzling on its face. Below the surface, though, the men observed and felt Kellogg’s depth of humanity. Cpl. Lucas captured it this way: “He is rough and very profane but has a heart as large as ever beat in man’s bosom.”

Colonel Kellogg and his 2nd Heavies passed over a year in the forts. And then came the spring of 1864, perhaps the most crucial period of the war in the East. After three years of fighting, the Union seemed no closer to victory. But Ulysses S. Grant, the hero of Donelson, victor at Vicksburg and breaker of the siege at Chattanooga, had other plans. In his new role as lieutenant general and overall commander of all federal forces, he initiated the Overland Campaign into the heart of Virginia to take on Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Confederate Army. To hit Lee hard and continually, Grant needed all his resources. He called out men from the D.C. forts, including the 2nd Heavies.

The regiment’s historian recorded the moment. “It was about one o’clock on the morning of the 17th of May, when an orderly galloped up and dismounted at headquarters near Fort Corcoran, knocked at the door of the room where Colonel Kellogg …lay soundly sleeping, drew from his belt and delivered a package… as little conscious that he had brought the message of destiny to hundreds of men as the horse which bore him.”

Grant’s orders—the “message of destiny”—would forever alter the lives of the 2nd and hundreds of families in the quiet hill towns back home in Litchfield County.

“Grant needs us,” wrote Frederick Lucas, now the regiment’s sergeant major, to his mother, “and we are ready & eager to aid him.”

As Kellogg read the order aloud, the men caught their breaths. Grant directed the regiment to leave its big guns behind and join the Army of the Potomac near Spotsylvania Court House. Kellogg’s adjutant, 1st Lt. Theodore F. Vaill, perhaps spoke for many when he confessed, “No matter how long a man has been a mere denizen of the unthreatened Camp, drilled, mustered, and rationed—no matter how much blank cartridge firing he has done,—when at length he realizes that he must go to the front, and hear the ultimate arguments in the great debate of war, he feels a certain sinking of the heart, as though the lead of the enemy had already lodged there.”

Days later, the 2nd Heavies pounded down dusty Virginia roads on the way to the front with rifled muskets slung over their shoulders. “Grant needs us,” wrote Frederick Lucas, now the regiment’s sergeant major, to his mother, “and we are ready & eager to aid him.”

They reached Spotsylvania on May 20 and joined the weary and exhausted Army of the Potomac. Throughout the last week, it had repeatedly assaulted a four-mile stretch of entrenchments occupied by Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The 2nd Heavies looked about them at the muddy soldiers crouched in their entrenchments, and listened to the shells that screamed overhead. Sgt. Maj. Lucas fired off a hurried letter to his mother from the battlefield, south of the Rebel entrenchment and only a few rods from the headquarters of Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, “These Generals are living just as we are in shelter tents on the ground. This is action service & real soldiering with no boys play about it.”

Lucas also wrote about the reception he and his comrades received after joining the battle-hardened veterans of the 6th Corps. These men took one look at the 2nd Heavies’ uniforms—natty in comparison to their own rags—and taunted them: “‘How are the Washington Pets?’–‘White gloves & shiny brasses.’” The worst jeer was “Bandbox regiment!”, referring to ladies’ decorated boxes used to store fancy clothing articles like gloves and bonnets.

The men didn’t have long to stew in their mortification. Kellogg received his orders, and with the rest of the 6th Corps, the 2nd Heavies hit the road. On June 1, they reached a small, ramshackle settlement called Cold Harbor. Here, Kellogg called a halt and the exhausted men dropped to the ground after ten days of ceaseless marching and maneuvering. A few minutes later, more columns of footsore Union soldiers arrived, and artillery batteries and ammunition trains rolled in. One of the 2nd Heavies noted, “We were so nearly dead with marching and want of sleep, that we hardly heeded these movements, or reflected on their portentous character.”

Kellogg paused his troops in a patch of woods. Before them stretched a plain, with Confederates waiting in a wooded hollow on the far side. Lee’s troops had arrived the day before and immediately had set to work with shovels to build entrenchments protected by embankments. Across the banks they constructed a hasty abatis, laying pine branches and small trees on its slopes to impede the enemy.

Behind the Confederate trenches lay artillery. Before long, shells hurled from the mouths of cannon sheared off tree limbs above the waiting Connecticut troops. A private in the ranks remembered, “Col. Kellogg wearing his old straw hat walked back and forth in front of the regiment and watched the shells explode around him.”

Union artillery also fired by this time. As the shells flew, Kellogg prepared his troops for their first-ever assault. They were going to lead the Union charge. Using bare ground as a canvas, he marked out the shapes of what he saw in front of the regiment and coached the officers on troop dispositions and other details.

As the 5 p.m. start time approached, Kellogg addressed his Heavies. In a grave tone, he “spoke of our reputation as ‘a band-box regiment,’” and “‘Now we were called on to show what we could do at fighting; he felt confident we would in this, our first fight, establish, and ever afterward maintain, a glorious reputation as a fighting regiment,’” noted the regimental historian. Kellogg added, “Now men, when you have the order to move, go in steady, keep cool, keep still until I give you the order to charge, and then go arms a-port, with a yell. Don’t a man of you fire a shot until we are within the enemy’s breastworks. I shall be with you.”

True to his word, Kellogg remained with the men. The regimental historian described what happened next. Kellogg placed himself in front of the column and instructed his majors to follow at intervals of one hundred paces. He gave the command “Forward! Guide Center! March! “They advanced towards the enemy, the regiment’s first battalion leading the way with the colors in the center. Moving in double-quick time, the men moved through scattered woods and an open field, then moved into another wooded area covered in pine. Kellogg cheered them on as they passed a line of abandoned rifle pits and ran up sloping ground until reaching an open hollow where they discovered the abatis-covered entrenchments. Kellogg and his Heavies were about 15-20 feet away when a hail of Confederate musket hit them. “A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near that it seemed to singe the men’s faces, burst along the rebel breastwork,” explained the historian. In this moment a long line of Confederate infantry hidden on the left flank of the Heavies let loose a barrage of musket fire. “It was the work of almost a single moment,” wrote their shocked adjutant. “The air was filled with sulphurous smoke, and the shrieks and howls of more than two hundred and fifty mangled men rose above the yells of triumphant rebels and the roar of their musketry.”

“A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near that it seemed to singe the men’s faces, burst along the rebel breastwork…”

The barrage broke the advance as some of the Heavies dropped to the ground and others continued on, only to be stalled in front of the tangle of felled trees and branches of the abatis. In the midst of the carnage and chaos, Kellogg remained on his feet, wounded in one arm and bleeding from another wound in the cheek. He shouted “About Face!” Before he gave his next command, another bullet struck him in the head and he fell dead.

As withering rebel musket fire poured into the ranks from the front and left, and artillery shells flew overhead, whatever was left of the Heavies’ line wavered. In this dire moment a new voice rose above the din of battle. “LIE DOWN!”

The man who uttered these words was the general in command of the brigade to which the Heavies belonged—24-year-old Emory Upton. The regimental historian remembered how the young brigadier “cried out with a voice that no man who heard it will ever forget—‘Men of Connecticut, stand by me! We MUST hold this line!’ It brought them back and the line was held.”

Night settled in, and the sounds of fighting gave way to groans of men incapacitated by shattered bones and other injuries. Calls for help, water and death floated through the darkness. Union reinforcements eventually arrived and the Confederates fell back. The light of day revealed the aftermath of the life and death struggle that had hallowed this ground.

“The field in front of us…was indeed a sad sight,” wrote Martin T. McMahon, a 6th Corps general. He went on to describe “a mute and pathetic evidence of sterling valor.”

McMahon continued, “The Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery…had joined us but a few days before the battle. Its uniform was bright and fresh; therefore its dead were easily distinguished where they lay. They marked in a dotted line an obtuse angle, covering a wide front, with its apex toward the enemy, and there upon his face, still in death, with his head to the works, lay the Colonel, the brave and genial Colonel Elisha S. Kellogg.”

A staff officer confirmed the report. “I went over where the centre had rested … on the top of the abatis the Colonel lay dead; and near him a score of our brave boys had fallen; he was shot through the head just above the ear—two shots near together—he was also shot in the arm, and face.”

Kellogg’s body, reported the regiment’s historian, “majestic even in death, was placed upon a rubber blanket and borne with labor from the field; and as it passed along, the men looked down with wonder upon the lifeless clay, half questioning within themselves whether the old lion would not rouse himself and scatter all his and his country’s foes.” He was 39 years old.

The regiment’s final tally of casualties numbered more than 300: 121 killed in action or died of wounds, 190 wounded, 15 missing and three captured.

From here on, no one referred to the Heavies as bandbox soldiers.

Back home in Connecticut, anxious families in Litchfield and surrounding villages gathered to scan an extra edition of the Litchfield Enquirer, which listed the regiment’s dead and wounded. With sinking hearts, mothers, fathers, wives and grandparents read through scores of familiar names, hoping their soldier wasn’t among them.

For those families who lost a son or husband, a new and painful chapter of life began. Such was the case for Kellogg’s wife, Polly, and 7-year-old son Edwin. They experienced some sense of closure when Kellogg’s remains were transported to Connecticut and buried in a cemetery in the village of Winsted.

“Cold Harbor!” said a Salisbury, Conn., man nearly five decades later; “those syllables came to have a dreadful sound in hundreds of Litchfield homes.”

The 2nd Heavies went on to fight at Petersburg, Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, Cedar Creek and Hatcher’s Run. Its last action occurred on April 6, 1865 at Little Sailor’s Creek. When the survivors mustered out after the war’s end, only 183 original soldiers remained.

They never got over the loss of their colonel. The regiment’s historian wrote, “This mighty leader, though falling in the very first onset, yet went on through every succeeding march and fight, and won posthumous victories for the regiment which may be said to have been born out of his loins. Battalion and Company, officer and private, arms and quarters, camp and drill, command and obedience, honor and duty, esprit and excellence, every moral and material belonging of the regiment, bore the impress of his genius.”

References: Diary of Michael Kelly, 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Conn.; Vaill, History of the Second Connecticut Volunteer Heavy Artillery: Originally the Nineteenth Connecticut Vols.; Barker, Dear Mother from Your Dutiful Son; The Civil War Letters of Lewis Bissell; McMahon, “Cold Harbor,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 4; Norton, “Salisbury in War Time,” address given by Thomas Lott Norton, Salisbury, Memorial Day in 1901.

Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel co-authored Heroes for All Time: Connecticut Civil War Soldiers Tell Their Stories, a book featuring the images, artifacts and exploits of the citizen soldiers who made up the regiments from Connecticut who volunteered to save the Union and fought to set men free in the Civil War. They are both former players for the Panthers Hockey Club.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.