By Brian T. White

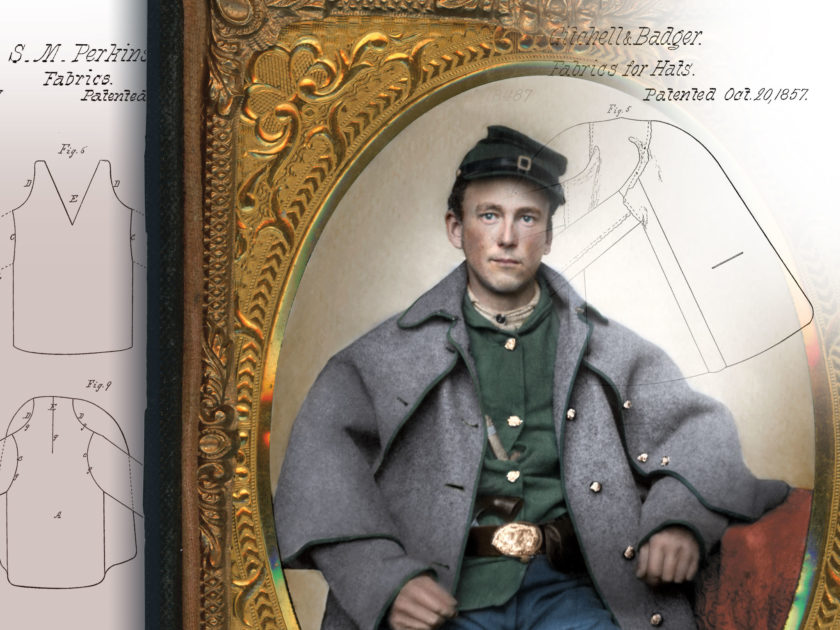

The North’s volunteer army used scores of unusual pre- and early-war inventions. One, the seamless felt overcoats of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, proved an innovation of limited utility on campaign and unfortunate circumstance in combat.

Samuel Perkins of Springfield, Pa., first patented the pattern and method of construction on Jan. 25, 1853. Unlike traditional woolen cloth made from fiber spun into yarn and woven on a loom, felt was created by compressing, wetting, and heating “bats” of loose wool fiber until interlocked. Using an overcoat as his example, Perkins described the manipulation of wool by batting into the basic shape of the desired garment, and then “shrunk by a process analogous to the ordinary felting process,” before further shaping on wooden forms until dry. The coat was then trimmed to the taste of the customer.

Seamless clothing, especially outerwear, soon became the rage. Perkins founded the Seamless Clothing Manufacturing Company in Matteawan, N.Y.

Meanwhile, tweaks to the original method benefitted the product. On Oct. 20, 1857, company assignors Delos W. Gitchell and Luther W. Badger filed a patent with improvements. While the core manufacturing details appeared similar, Gitchell and Badger updated Perkins’ methods of felting and shrinking the garments. They used mechanized “jigs or hardener plates” to felt the garment components together before placing them into a fulling mill to shrink the garment. This technique improved the evenness in the cloth and further strengthened the bonds of joined components. The garment continued shaping on wooden forms until dry and trimmed. These improvements yielded a more waterproof and robust garment. They also allowed a degree of mass-production unattainable only four years earlier.

During these years of innovation the Seamless Clothing Manufacturing Company operated stores at 39 Murray Street in New York City and 113 Battery Street in San Francisco. They also sold their unique garments to a host of clothiers throughout the country.

By the outbreak of the Civil War, features in Scientific American and New American Cyclopædia, and a glowing review by a sailor aboard the U.S. Navy frigate Niagara, solidified the popularity of seamless garments.

The ability of seamless overcoats to shed water in foul weather and the manufacturer’s ability to customize the coats caught the attention of Col. Hiram Berdan. In late 1861, the engineer, inventor and crack marksman ordered the overcoat for his two sharpshooter regiments, then mustering at Weehawken, N.J.

Per Berdan’s contract with one Col. Fenton, the overcoats were to be “gray…[with] gutta-percha buttons, and with green trimmings.” Made unlined and with capes detachable from under the collar by hooks and eyes or buttons, most of these overcoats had green binding trim and Goodyear patent rubber buttons bearing the U.S. coat of arms. According to an 1861 newspaper article describing the sharpshooters’ appearance, the gray overcoats and matching Whipple patent seamless caps appeared part of a rudimentary attempt at winter camouflage.

Wartime expediency prompted some complaints. Berdan stated in an Oct. 22, 1861, letter to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan that the manufacturer “had several hundred overcoats on hand, trimmed with red [and with] metal buttons, which he wished me to take.” Berdan declined and received 300 to 400 overcoats for the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters trimmed per his original order. The balance, however, was later received with the red trim and metal buttons. This issue was never resolved for the men of the 1st regiment. But the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters apparently received the prescribed green-trimmed overcoats.

The garments were initially popular among the enlisted men after proving their worth on cold, wet nights of guard duty. The same soldiers discovered to their dismay that, after repeated use, soaked overcoats became stiff as a board.

A serious and deadly complication involved the color. On the night of Sept. 29, 1861, Companies C and E of the 1st participated in their first engagement at Munson’s Hill, Va. These companies, formed of sharpshooters from Michigan and New Hampshire, went into combat in their gray overcoats and caps. They encountered the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry, who fired at them. The sharpshooters hit the ground and fired back at the Pennsylvanians, who, as it happened, also wore gray uniforms. Soon after, the sharpshooters realized they had engaged in a friendly-fire situation and halted their volleys. Meanwhile, the men of the 71st panicked in the face of the sharpshooters’ fire, and fell back in confusion. At this point, their own cavalry charged them, having mistaken them for Confederates.

When losses were tallied at the end of this tragedy, one sharpshooter suffered a wound. Casualties in the 71st included four dead and 14 wounded.

An outraged Sgt. Francis Donaldson of the 71st angrily lamented, “And pray who is responsible for great loss of life? Who is responsible for sending upon such an expedition men dressed in the garb of the enemy?” 1st Lt. William P. Austin of the sharpshooters later observed, “The ground over which we had advanced during our midnight struggle was marked by our gray overcoats, the boys throwing them off to prevent being fired upon by other Union men.”

Despite the confusion at Munson’s Hill, the sharpshooters retained their overcoats. During the winter months of 1861 and 1862, they provided a degree of warmth within their Washington, D.C., training camp.

The following spring was another matter. On April 4, 1862, the 1st arrived on the outskirts of Confederate-occupied Yorktown. The regiment deployed as skirmishers and advanced at a crawl to points opposite the enemy earthworks. Some wore their gray overcoats, and many more the matching Whipple caps. After some point, the sharpshooters’ own supporting skirmish line of infantry began taking potshots at them, fortunately having no effect.

The sharpshooters had enough of the disadvantageous overcoats. Within days, an order went out to turn in any remaining gray clothing, and to draw the army pattern sky blue infantry overcoat. Regimental QM Sgt. Eugene Rowlson tersely noted in his diary “stowed gray coats & caps” before conducting the boxed garments into storage at the advance-clothing depot in Washington. The 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, then serving as part of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s corps, retained their gray overcoats only a few weeks. The men discarded them soon after their arrival in Falmouth, Va., in mid-April 1862.

The fate of the gray seamless felt overcoats was sealed.

The author has yet to learn what ultimately became of the early war Berdan’s Sharpshooters overcoats. One example appeared in a circa-March 1864 photograph of Army of the Potomac scouts and guides. Sagging and missing its cape, this lone late-war example exists as a tantalizing glimpse at the utility of surplus cast away garments being pressed into a semi-military service.

The seamless overcoat had proved nuisance enough for it never to be issued to soldiers for the rest of the war.

References: Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865; Acken, Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experience of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson; Perkins, S.M., U.S. Patent 9,557, 1853; Gitchell, D.W. & Badger, L.W., U.S. Patent 18,487, 1857; Fox Lake Public Library’s Fox Lake’s Civil War News & Letters; National Archives, Record Group 94, Regimental Record Group of the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters; New York Tribune, Oct. 15, 1861; Rowlson, 1861-1862 Diary, private collection.

Brian T. White has researched the men and material culture of the Berdan’s Sharpshooters for more than 20 years. He is an avid collector of wartime sharpshooter photographs.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.