By Kurt Luther

In photo sleuthing, most of us strive to set a high bar for what constitutes sufficiently strong evidence to identify an unknown soldier portrait. The gold standard might be finding an identical or nearly-identical view with the subject’s name in period ink, or identified in a published book or institutional archive. We often think of these identifications as airtight. But what happens when these gold standards turn out wrong? In this column, I explore this question by revisiting an old investigation, armed with fresh evidence from an astute reader, and provide new answers.

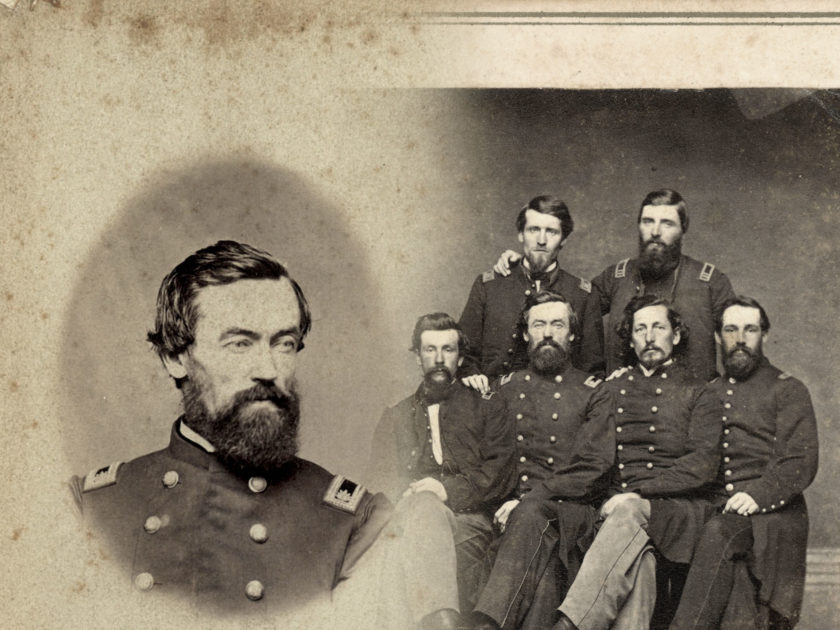

In the Autumn 2016 issue of MI, I wrote about identifying a group portrait of six Union officers. I identified one of the field officers, Col. John Morrill of the 64th Illinois Infantry, based on his distinctive appearance and a brute-force search of reference books. From that lead, I made a concurrent service timeline to determine which fellow officers served in the 64th at the same time as Morrill, and then tried to match these to identified reference images.

Author’s collection.

Each identification narrows down the window of possibilities for the yet-unknown subjects in a group portrait. For example, I matched one man—a field officer with bushy eyebrows and a distinguished beard—to an identified carte de visite of Lt. Col. Michael W. Manning in the Boys in Blue Collection of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum (ALPLM). Manning was promoted from captain in February 1864, and Morrill was reassigned after a July 1864 battle wound. Therefore, the timeline suggested all four remaining men must have served during that 5-month period.

Consequently, I was able to identify three officers, Capt. Charles I. Conger, Capt. Joseph S. Reynolds, and Lt. Duncan Reid, based on their service records and multiple reference images. The fourth man, a bearded lieutenant with staff buttons, looked to be an assistant surgeon but remained unidentified, owing to a lack of reference images of either candidate, Henry A. Mix and William D. Plummer.

After that story was published in MI, Doug Sagrillo of Lakewood, Colo., a collector of 64th Illinois portraits, reached out to me with several images I had never seen before. These included a carte de visite of the man I knew from ALPLM as Michael W. Manning. The distinctive visage was undoubtedly the same, though the view and photographer (J.S. Porter of Ottawa, Ill.) differed. The problem was that Sagrillo’s carte included a period ink inscription: “Dr J T Stewart, Surgeon, 64 Reg. Ill. Vol.”

Which name was correct? I considered ALPLM, the official presidential library of Abraham Lincoln, an authoritative source. Yet, Sagrillo’s carte directly contradicted its information. Returning to the ALPLM digital collection, I noted its portrait of the man was indeed inscribed “Lieut. Col. Michael W. Manning.” But this label appears to have been added by the previous owner, an Illinois bookstore, in 1969.

The inscription on Sagrillo’s carte, clearly from the Civil War era, seemed more credible by comparison. Yet, I worried that this inscription lacked a valediction, such as “Your friend” or “Yours truly,” to signal an autograph. What if the subject had simply written the name of the portrait’s intended recipient, rather than his own?

While this was an important question to answer, it also reflected my determination to learn from my earlier mistakes. As I noted in my Summer 2016 MI column, inscriptions should be treated with skepticism. My original identification increasingly looked wrong, and the fact that I relied on a trusted archive was cold comfort. I sincerely did not want to misjudge the identity again.

Besides the inscription, “Dr J T Stewart” appeared to be the more convincing identity in other ways. The officer in the ALPLM portrait wore shoulder straps with lettering between the oak leaves, possibly “MS” for “Medical Staff”—a clue that nicely fit James T. Stewart, the 64th’s regimental surgeon. But it was hard to square it with Manning, the lieutenant colonel. Likewise, the group portrait showed this man wearing the staff buttons and dark pants typical of surgeons and staff officers.

Stewart’s service record also placed him with the regiment during the February-July 1864 window. But I had previously ruled him out after finding an identified photo of Stewart (notably, also attributed to ALPLM), depicting a different man who was obviously not present in the group portrait. Now, I suspected this man, too, was misidentified.

Doug Sagrillo provided some supplementary sleuthing to settle the issue. In a digitized copy of Physicians and Surgeons of the West (1900), he had located a biographical profile of Dr. Stewart, including a portrait that showed a man with the same unmistakable eyebrows and beard as in the group portrait and ALPLM carte, albeit several decades older. He had died in 1901, a year after the biography was published, and was buried in Peoria, Ill.

With the field officer finally confirmed as Stewart and not Manning, my next step was to consider how the other officers’ identifications might be affected. Unfortunately, Manning’s promotion from captain had bookended the group portrait to February 1864 or later. In contrast, Stewart was the regiment’s original surgeon, since late 1861. To update the concurrent service timeline, I had to widen the window by five months to August 1863, when Joseph S. Reynolds received the captain’s bars he wears in the group portrait. Consequently, six more officers once eliminated by the Manning timeline reemerged as candidates for the still-unknown sixth officer.

“Research is fundamentally both a human process and a social one. Sometimes we build on imperfect work conducted by others. On other occasions, a gracious colleague helps us realize when our own work can be improved.”

I wish I could report that one of these six resurrected officers proved the mystery officer. But reference photos quickly ruled a few of them out. Yet, correcting Dr. Stewart’s identity did shed new light on this final mystery. When Manning was named as the field officer, his staff buttons and dark trousers might be explained away as idiosyncratic. With Stewart, a simpler story emerges: he simply followed uniform regulations for medical staff. His identification lends support for the theory that the mystery officer, the only other man in the group portrait also wearing staff buttons and dark pants, is also medical staff. Thus, the case is strengthened for this officer as one of the two assistant surgeons, William Plummer or Henry Mix, whose service records still fit the expanded timeline. Sagrillo has since located a wartime carte of Plummer and a postwar lithograph of Mix, which may allow us to unlock the last secrets of this image.

Misidentifications are a difficult side of photo sleuthing; and admitting when we are wrong can be even harder. Despite our best intentions, and even when we are careful and thorough, mistakes can still happen.

Research is fundamentally both a human process and a social one. Sometimes we build on imperfect work conducted by others. On other occasions, a gracious colleague helps us realize when our own work can be improved. As long as we strive to correct our errors, we can ease the path for fellow sleuths, and bring all of us a step closer to understanding the past.

We also welcome your feedback on CivilWarPhotoSleuth.com, either via email or by submitting the feedback form on CWPS. We will continue to make regular updates and improvements, announced through our Facebook page and elsewhere.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.

© Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.