By Scott Valentine

Trench warfare along the earthworks defending Petersburg, Va., settled into a brutal rhythm of seemingly endless assaults and counterattacks soon after it began in June 1864. The campaign against the city stretched into a 10-month test of courage, and witnessed some of the most vicious combat of the war. When it ended in early April 1865 with the fall of the city and nearby Richmond, close to 180,000 combatants had participated in the siege, and produced an estimated 42,000 Union and 28,000 Confederate casualties. The vignettes here, all northeastern men, represent the experiences of soldiers from all the states. They illustrate the capricious nature of warfare, and a few of the many who suffered its wrath.

The Fading Regiment

Sitting in a trench just outside Petersburg in the stifling July heat, Adj. George C. Case pondered the events of the previous two weeks. He concluded that Petersburg would once again remain beyond the reach of the Army of the Potomac. His regiment, the 57th New York Infantry, had been mauled on June 16, 1864, in a 4-day engagement that went down in history as the Second Battle of Petersburg. He had suffered a flesh wound in the neck in the action. The regiment suffered further losses in skirmishes during the days that followed.

As beads of sweat ran down his face, Case carefully recorded the names of the 75 officers and men who had become casualties from June 15 to June 22. He reckoned that the regiment had but a handful of men fit for active duty. With no end to the bloodshed in sight, Case thought that if the regiment didn’t receive fresh recruits soon, it would soon disappear.

Case was known among the men of the 57th as a steady officer under fire and a kind and generous man. The son of a whaler, he had lived and worked as a merchant on Shelter Island, a small island of about 500 souls nestled between the two forks of eastern Long Island in New York. When the war came, he became one of the earliest of its 31 male residents to join the army. He enlisted in the 57th in November 1861, and worked his way from private to commissary sergeant to second lieutenant, and then to first lieutenant and regimental adjutant.

By the time of the Petersburg Campaign, the 57th had left a trail of dead and wounded across most major engagements in the Eastern Theater. On July 14, 1864, soon after Case made his list of wounded, the regiment began to muster out by company ahead of the end of its 3-year enlistment, which technically ended in November. New recruits and veterans transferred to the 61st New York Infantry, and the regiment ceased to exist on Dec. 6, 1864.

Case returned home to Shelter Island. Seeing little opportunity, he followed the lead of many Union veterans who sought government positions. By 1870, he worked as a clerk in the Customs House in New Orleans, La. Eight years later, yellow fever swept through the city and claimed many lives, including Case. He was about 40 years old.

Fountain Shower

First Lt. Frank H. Kempton of the 58th Massachusetts Infantry recalled the infernal din of battle at The Wilderness and Spotsylvania. These sounds, however, were but a whimper compared to the result of the detonation of an underground mine on July 30, 1864.

Standing at the head of Company A, Kempton marveled at the debris hurled into the air by the massive explosion. In that moment, about 300 Confederates of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina infantries and Pegram’s artillery battery were buried under an earthen hail. A private in the 100th Pennsylvania Infantry described the event. “In a few minutes a heaving and trembling of the earth followed by a heavy explosion, and a huge mass of earth arose in the air with all the contents of the fort, caissons, timbers and guns, small arms, haversacks, blankets, and the soldiers of the garrison. It resembled a huge fountain, the mass seemed to stand still when it reached its height and fell as a shower from a fountain.”

Kempton didn’t have much time to muse over the explosion, for his regiment was ordered to advance immediately. He and the 58th charged into the massive depression with about 9,000 other Union troops of Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie’s 1st Division of the Ninth Corps. The troops initially met little or no resistance from the Confederate defenders, but squandered their advantage by milling about in the crater for 15 minutes, while its officers tried to organize their men and decide what to do next.

One of Kempton’s comrades, Capt. Everett S. Horton of Company C, described the confusion.

“After having filed a portion of the regiment to the west of the fort I found that the balance of my regiment was not following, and upon going back to ascertain why the balance of the regiment did not follow I found that they had been ordered by another officer to file to the right of said fort, which split the regiment in two. I then received orders from the officer who was in charge of the right of the regiment to charge upon the works to the west of said fort; all this under a heavy fire, both artillery and musketry. They then broke and fell back to the ditch or saps in the rear of the fort. We remained here in the pits or saps, mingled with other troops, the heat being very oppressive and the men almost famished for the want of water. We remained in this place until the enemy charged upon us, and then a charge was made by the colored troops, and they came in upon us tramping us under their feet, which made it impossible for us to accomplish anything, and at this time the enemy were pouring a deadly fire upon us, and those of my command who did escape did so by climbing over the fort. At this time the men in the ditch or saps were surrendering to the enemy or being cut down.”

Confederates captured Kempton and most of his company in the ditch in the rear of the fort. Confined at Camp Asylum in Columbia, S.C., he gained his parole on March 1, 1865, returned to his regiment, and received a promotion to captain. He mustered out in July 1865 and lived until 1912.

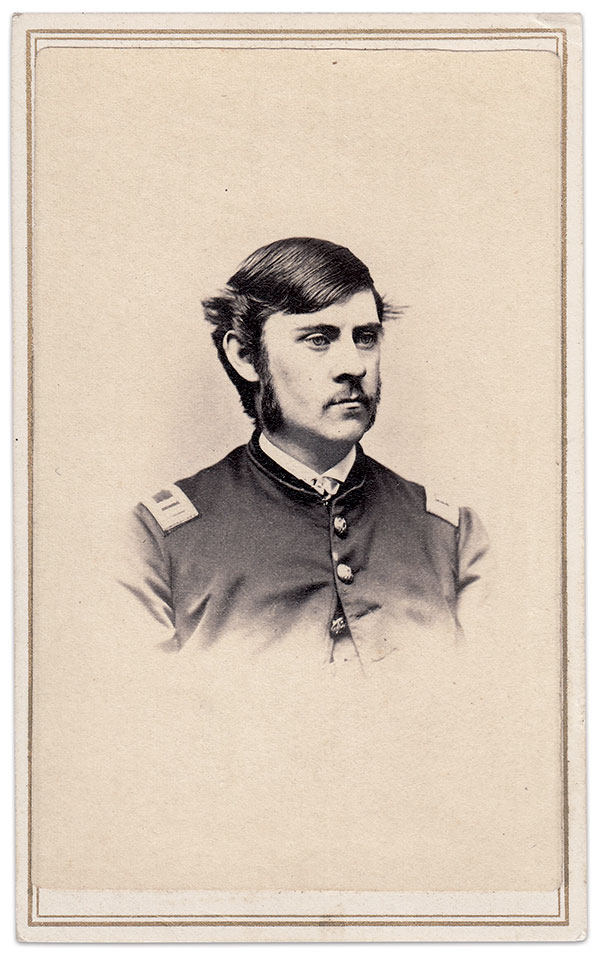

The “Boy” Is Struck Down

As 2nd Lt. Arthur V. Coan and Company G, 146th New York Infantry advanced doggedly through dense undergrowth of pine and stunted oak, the sharp crackle of Confederate musketry and the distant boom-boom of a section of artillery disturbed the sultry still air of the August morning.

Coan was still brooding about having to give up his dandy looking Zouave uniform back in February for the ill-fitting frock coat and pantaloons of an officer. Although most of the enlisted men of the regiment now wore the regulation blue uniform, a sprinkling of men wore the distinctive French style “Turco” Zouave uniform of light blue with yellow trim. The loose-fitting uniform would have been better suited to the infernal summer heat. Coan and Company G had begun their advance that morning from Globe Tavern, Dinwiddie County, Va. They had marched astride the Weldon Railroad for about six miles before coming under sporadic artillery and scattered small arms fire from enemy skirmishers.

It was 11 a.m. on Aug. 18, 1864—the beginning of the Battle of Globe Tavern.

Coan and his fellow New Yorkers entered a cornfield in the vicinity of the W.P. Davis House. As they did so, two Confederate brigades under the command of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth emerged from the woods on the opposite side of the cornfield and advanced in two lines of battle. They hit the 146th and other federals on the front and left flanks with such force that retreat was inevitable.

Coan had just turned to his left to dress his lines, which had become misaligned during its advance, when he was struck repeatedly by enemy shots. He fell severely wounded, and comrades hurriedly carried him to the rear.

The loss of Coan deprived the regiment of one of its most popular officer. The men of his company called the 20-year-old Coan “Boy” because of his height and slight build. They mothered him mercilessly—but with good intent. Perhaps to prove his maturity, he cultivated a beard and mustache. But the sparsity of his facial hair only served to increase the mothering of his men. In this case, Coan was beyond mothering. He died of his wounds in a U.S. General Hospital on Sept. 30, 1864.

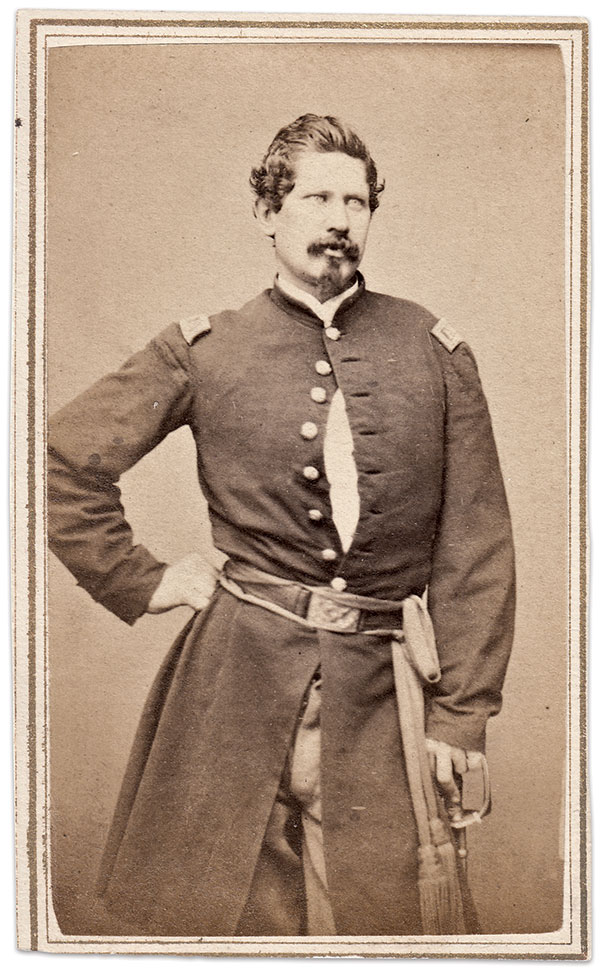

Close Quarter Brawl

The days felt cooler, especially during the early morning, as the summer of 1864 drew to a close. In both armies, a rumor circulated that they would be ordered to winter camp earlier than anyone expected.

But Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had other ideas. He planned to probe the Petersburg defenses until they gave way.

Just before daylight, on Sept. 29, 1864, 1st Lt. Samuel S. Foss and his comrades in the 8th Connecticut Infantry halted on the Varina Road near Cox’s Woods. They were part of a column that included the rest of the 2nd Brigade, part of the 1st Division of Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord’s Eighteenth Corps. Ahead of the brigade, according to one officer, “skirmishers found the pickets of the enemy near the woods and drove them rapidly up the road some two miles to the open field in front of Fort Harrison.” The column halted near the edge of the woods, where Foss and the Connecticut boys deployed in a line of battle behind another regiment in their brigade, the 96th New York Infantry. Behind them stood the 1st Brigade.

Foss faced Fort Harrison and wondered how the hell anyone could survive an assault against its formidable defenses. But before he could further consider the matter, orders arrived to take the fort. An officer described what happened next. “Nearly half of the distance between the woods and the fort was passed with little protest from the fort or its flanking works. But as the notion that the fort had been abandoned began to obtain, flashes of blaze and puffs of smoke were seen along its front, and the screaming contents of fifteen pieces of artillery passing over our heads went crashing into the woods in our rear, doing some damage to our reserves. The range was too high, but after a few shots some reached our advancing brigade.”

Foss and the rest of the attackers rushed across the open field under severe enemy artillery fire until they reached cover in the ditch at the foot of the fort’s parapet. Because of an error in the fort’s construction, its guns couldn’t be depressed low enough to hit the men in the ditch. After a short pause, the federals rose to their feet and swept up and over the parapet. A brief but desperate close quarter brawl ensued, during which Foss suffered a severe hip wound, and Fort Harrison was captured.

Foss survived his wound and rejoined his comrades after several months of hospital care. He mustered out at the expiration of his term of service on Jan. 29, 1865.

After the war, Foss and family moved to Bay City, Mich. He and his brother, Edgar, formed a successful lumber business. In 1883, Foss was thrown from a buggy and killed. His wife, Rebecca, and their two children survived him.

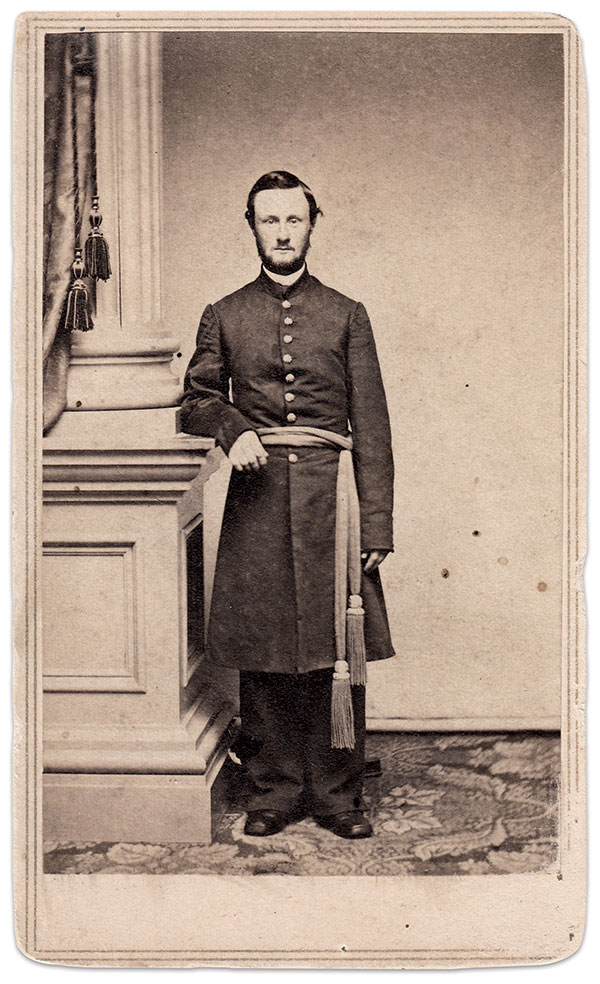

Gilfillan’s Troubles

In early October 1864, Capt. John M. Gilfillan rejoined his comrades in the 39th New York Infantry after a long convalescence. He had been out of commission from a shoulder wound received five months earlier at the Battle of Spotsylvania.

Though back with the regiment, popularly known as the Garibaldi Guard after the Italian revolutionary, Gilfillan’s shoulder caused him much discomfort. To ease the pain, he likely turned to a shot glass of spirits. He would not be the first or the last soldier to turn to liquor to deal with the discomforts of camp, loneliness, boredom, fear, cowardice and sorrow.

Union army regulations permitted officers to purchase and consume alcoholic beverages, provided they were off duty and did not overindulge. Officers also enjoyed the privilege of privacy that rank afforded them to have a drink whenever the mood struck them. It therefore comes as no surprise that the habit destroyed many an officer’s career.

Gilfillan’s troubles began soon after he became a captain in the regiment in January 1864. He was arrested for drunkenness and absence from dress parade and confined to camp. His motivation for drinking may have resulted from the length of his service, dating to 1861. He served in two Empire State regiments prior to joining the Garibaldi Guard. Another factor may have been the death of his brother, William, a captain in the 43rd New York Volunteer Infantry who fell mortally wounded at Gettysburg.

Whatever the reasons, Gilfillan’s punishment for this first offense ended with his release from confinement the following month. He applied for a transfer to the navy, and celebrated the impending move by drinking himself into a stupor with a fellow officer. Hauled before the regiment’s lieutenant colonel for the new offense, Gilfillan balked and told him off. He was slapped with a charge of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, and his application to join the navy denied. Gilfillan was confined again. But with the spring campaign season about to begin, he was released and ordered to report for duty.

Then came Spotsylvania.

On May 12, Gilfillan and the 39th happened to be in the forefront of the Second Corps’ 20,000-man attacking force against Confederates in the Mule Shoe Salient. After scoring an initial success, the rebels counterattacked and overran a large part of the Union troops. Gilfillan suffered a severe shoulder wound about this time at the head of his company. The 39th lost its flag in brutal hand-to-hand fighting.

Gilfillan spent much of the rest of the spring and summer convalescing. He returned to the regiment in the autumn—and to alcohol.

On March 14, 1865, Gilfillan and two other officers of the 39th were arrested for drinking while on duty and confined to quarters. The following day, Gilfillan requested and received a medical discharge for his wound—a dignified exit for a troubled man who proved a brave officer. He lived until 1890.

Scott Valentine is an MI Contributing Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.