By Ben Myers

Alpheus Starkey Williams sat calmly on horseback, an unlit cigar characteristically grasped between his lips. Before him stood his “Red Star” division—the first division of the Twentieth Corps—5,000 suntanned, battle hardened men, cracking jokes and conversing as they rested, awaiting his next order that would call them to action. Perhaps, as he surveyed their faces, he noted the strong men who had volunteered as mere boys. His thoughts may have also drifted to those missing, dear comrades and friends cut down by a hail of bullets at dozens of engagements, through which he himself had somehow emerged unscathed.

He hadn’t long to reflect on it though, for soon it was time to call his brigades to attention. It was May 24, 1865. Peace had been restored to the Union, and the victorious Army of Georgia was setting off down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., on its last great military action, the Grand Review. Gen. Williams grasped his cigar a little tighter in his teeth, turned his horse to the front, and set off ahead of his men one last time.

The Reformer

As the Red Star Division stepped off into the sun of a beautiful spring day, Williams had already commanded some of his regiments for three-and-a-half years.

Williams had first met them in the fall of 1861, finding the raw recruits willing but severely wanting for drill and discipline. He immediately set to work in a flurry of paperwork, officer’s schooling, and drill. Within a month the brigade was turning evolutions at the double-quick “with the regularity of veterans.” In the same letter home, Williams added with pride, “I am well pleased with my brigade, and what is perhaps more important, I think the brigade is well pleased with me …”

His convictions were soon confirmed when the men took to affectionately calling their patient and fatherly brigadier “Old Pap.” At 51 years of age, and lacking a formal military education, Williams did not fit the typical model of a general. Most of his colleagues that wore a single star at the beginning of the war averaged 37 years of age. He had lived a long and varied life however; that one might argue had more than adequately prepared him for field command.

A native of Connecticut, Williams was born in 1810, orphaned by 17, and graduated from Yale in 1831. As would prove a common theme throughout his life, the pull of adventure took prevalence, and for the next several years he embarked on a tour of America and Europe, interspersing his law studies between trips. Funded by a $75,000 inheritance (nearly $2 million in today’s dollars), his tour also included the principal sites of historic military significance.

With his world travels and studies at an end, Williams chose in August of 1836 the booming Detroit, Mich., as his new home, and started a law practice. He married and started a new family in 1839, all the while enjoying successful business ventures, including serving as Probate Judge, the president of a bank, owner and editor of the Detroit Advertiser, and a four-year stint as postmaster.

Civic and military interests further supplemented Williams’ breadth of professional experience. He served in various civil offices, including the Board of Education. In 1836, he joined Detroit’s militia, the Brady Guards, and, by the time the Mexican American war broke out in 1847, had served as the Guards’ captain for several years. He was appointed lieutenant colonel in Michigan’s volunteer regiment. Upon arrival in Veracruz, he busily engaged in maintaining supply lines and communications, while fighting off guerrilla attacks in the shadow of Pico de Orizaba’s 18,000-foot peak. Although not glorious duty, Williams performed well. A year of commanding volunteers had provided an education in the needs and wants of soldiers that Williams would never forget.

Returning home, Williams ran into misfortune in 1850 when his wife died at only 30. Williams busied himself caring for his three children, and engaging in his numerous professional pursuits. He also took up command of a new militia, which would eventually be known as the Detroit Light Guard. By 1859, Williams assumed the rank of major, and commanded two companies.

At the time the first guns fired on Sumter in April 1861, Williams was Michigan’s foremost citizen soldier. He started readying the state militias after South Carolina’s secession in December 1860, and conducted a school of instruction for volunteers from June until August. His newly minted soldiers were the first western troops to arrive in Washington, D.C., prompting President Abraham Lincoln to exclaim, “Thank God for Michigan!”

Commissioned as a brigadier general of U.S. volunteers, Williams arrived in Washington in October 1861. It was then that he first met his brigade, and as he would in many commands and situations throughout the war, “began a reform.” The men would grow to love him for his integrity, skillfulness and bravery. He would lead them, and subsequently their division and corps, through some of the most savage fighting of the war.

Stonewall’s Opponent

With discipline instilled, the real test for the brigade and general came on May 24, 1862, at Winchester, Va. After a seemingly easy advance deep into the Shenandoah Valley, political appointee Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and his over-extended command—with Williams now in command of a division—were dealt a hard lesson by Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

It was Williams’ first combat action. Charged with slowing Jackson’s advance so Banks’ supply train could retreat, Williams recalled a few days later that the whiz of shells and bullets had an “exciting effect” upon his “unstrung nerves,” but that there was an “excitement about the banging of guns and rattling of musketry with the pomp and circumstance of war.”

Though the federals were outnumbered and unable to hold, Williams managed a withdrawal from the Shenandoah, with most of the valuable supply wagons escaping safely across the Potomac River and into Maryland. Williams believed that the situation could have easily been avoided if not for the failure of politicians in Washington.

The affair proved that although Williams cared for his men, he could execute sound judgment under pressing conditions and had no apprehensions about committing his soldiers in battle. His tenacity held later that summer at Cedar Mountain. His old brigade especially suffered as they charged, broke, and rolled up Stonewall’s line, before falling back for want of reinforcements.

For the remainder of August, the Union army retreated toward Washington under the pressure from the Confederates. Williams’ men suffered dreadfully, with many falling ill from malnutrition and exposure. With less than half of his men remaining, and now temporarily in command of Banks’ corps since the general “seem[ed] to get sick when there is most to do,” Williams vented in a letter home about the mishandled Second Bull Run Campaign, “our generals seem more ambitious of personal glory [than] of their country’s gain.” It was a theme to which he would often revisit.

Hard Service

Upon his return to Washington, Williams spent each day in a flurry of activity, trying to prepare his decimated corps, with few field officers present for active service. Soon, they went on the march again, pursuing Gen. Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland, a move Williams had predicted in a letter home over the summer. Near Frederick, Md., a soldier in one of Williams’ regiments, the 27th Indiana, found the “Lost Order,” which revealed Lee’s upcoming plans. Williams forwarded it at once to Gen. George McClellan, in charge of the Army of the Potomac. The plan gave “Little Mac” a great advantage to head off Lee.

As the armies converged on the small town of Sharpsburg, Williams cheerfully returned to divisional command, glad he had “got rid of an onerous responsibility” of corps command. Maj. Gen. Joseph K.F. Mansfield, a “very fussy” (in Williams’ opinion) regular army officer, who had never before held a field command, took the helm of the Twelfth Corps.

“I expect to live on hardtack and pork, without tents and roughly as a trapper. But I always feel in the best spirits when so living.”

On the eve of the battle, skirmishers popped off rounds throughout the night. Williams recalled that “the morrow was to be great with the future fate of our country.” He lied under the corner of a rail fence, and, despite his apprehensions, slept soundly.

The next morning the Twelfth Corps was ordered forward to reinforce Gen. Joseph Hooker’s attack into Miller’s cornfield. Mansfield deployed Williams’ division in awkward formation, unnecessarily exposing them to artillery fire. But within minutes, Mansfield fell mortally wounded. Williams took command of the Corps, and quickly deployed his regiments while under fire, including several green units. “The roar of the infantry was beyond anything conceivable to the uninitiated,” he recalled.

The Twelfth Corps fought tenaciously until the Confederates retreated back across the corn to the opposite wood line (the West Woods). After the battle, Williams rode over the field on his trusty steed, which he affectionately called ‘Plug Ugly.’ “In one place, in front of the position of my corps, apparently a whole regiment had been cut down in line,” he wrote home. “They lay in two ranks, as straightly aligned as on a dress parade.”

Faithful Brigadier

Earlier in the war, Williams proudly proclaimed in a letter home, “I court nobody—reporters or commanders—but try to do my whole duty and trust it will all come out right.” It was a credo from which he never deviated, often to his detriment as other, more vocal commanders sometimes claimed credit for Williams’ doings. He fumed that the “big staff generals get the first ear and nobody is heard of and no corps mentioned till their voracious maws are filled with puffing.”

After his meritorious and steady service through Second Bull Run and at Antietam, Williams’ associates assumed he would receive a promotion to major general and officially assume command of the Twelfth Corps. Instead, Williams handed the corps over to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, a West Point graduate, who Williams quipped “Was on the Peninsula, of course,” and therefore had formed associations with influential members of the Army of the Potomac. Despite his initial indignation, Williams eventually grew to respect Slocum, and they worked well together.

Back with his division, the war again found Williams at a little crossroads called Chancellorsville in the spring of 1863. On May 2, Jackson marched his division 26 miles around the Union flank and slammed into the unsuspecting Yankees of the Eleventh Corps. The corps shattered and withdrew at a run through Williams’ division, which was now exposed to the approaching gray wave.

“The crack of the musket was close at hand,” Williams recalled as he tried to deploy. But there was no time for orders. “Fortunately my two leading brigades … saw the disaster and came at a double-quick. Without a halt, and with a cheer that made the woods and the open space ring, the whole line rushed into the woods.” By Williams’ estimation, the rebel advance was halted within 15 minutes

Stabilizing the Union line not only averted further disaster, but also forced Stonewall Jackson to search for a weak point in the federal line at night. During his reconnaissance, Jackson suffered a mortal gunshot wound inflicted by his own men, as they skirmished with Williams’ scattered regiments. The episode ultimately removed one of the finest Confederate generals from the war.

Of the fighting that day and the next, Williams wrote home, “You must stand in the midst and feel the elevation which few can fail to feel, even amidst its horrors, before you have the faintest notion of a scene so terrible and yet so grand.

“You must stand in the midst and feel the elevation which few can fail to feel, even amidst its horrors, before you have the faintest notion of a scene so terrible and yet so grand.”

Williams did not wait long for another such scene. At Gettysburg two months later, Slocum assumed command of the Union right wing, and Williams the Twelfth Corps. Williams’ men were placed on Culp’s Hill, the crucial right flank of the line, against which the Confederates hurled themselves on July 2nd and 3rd. Employing lessons learned in previous battles, Williams had his men shelter between detached masses of rock and log breastworks, resulting in comparatively light casualties.

Williams’ performance at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg did not go without notice. Maj. Gen. Slocum and a few political advocates tried to secure Williams a major general’s star. But once again, the promotion did not come. Newspapers found more extroverted generals to laud in their coverage. The real blow came in the report of federal commander Gen. George Meade, who made no mention of Williams’ efforts, and misattributed the actions of the Twelfth Corps. Williams wrote home that he was “disgusted and chagrined,” but resigned himself to the duties at hand, always faithful to his command. “I prefer the love of the men to the favor of the government,” he wrote.

Go West

Williams’ frustrations with the Army of the Potomac in the eastern theater of war came to an end in October, when the Twelfth and Eleventh Corps went west to reinforce the Army of the Cumberland near Chattanooga, Tenn. Much to his disappointment, Williams’ first duty involved guarding crucial railroad line. An inactive campaign didn’t suit the general’s adventurous spirit. For the first time since the beginning of the war, he noted being ill with a “bad cold.” “I have nothing of interest to write,” he opened in a letter to his daughter at the end of November. “One day is like unto another.”

Williams earned a 30-day leave in Detroit at the beginning of the New Year—the first he had been away from his command and home in two-and-a-half years. It was the only absence he would take during the war.

Spring brought reorganization, and initiated new operations. Williams’ division became the first in the new 21,000 man Twentieth Corps, an amalgamation of veterans of the Eleventh and Twelfth corps that retained the Twelfth’s star badge as their emblem, with Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker in command.

On April 28, Williams wrote to his father-in-law, “I am off tonight for the front and within the month of May you will hear of stirring events. I expect to live on hardtack and pork, without tents and roughly as a trapper. But I always feel in the best spirits when so living.”

The adventurous brigadier had set his sights on Atlanta.

To Atlanta

For the next several months, Williams’ division and the Twentieth Corps took a beating as Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman pressed the Confederate defenses leading to Atlanta. At Resaca on May 14, one of Williams’ brigades successfully counterattacked a rebel division that had outflanked Sherman. One of the soldiers in his original regiments remarked to him that they had had a “splendid fight,” with “Old Pap right amongst us.”

So went the grind to Atlanta. Sherman’s army sustained blows, but it also dealt out the same thanks to the stalwart veterans among the ranks. Williams’ men added New Hope Church, Kolb’s Farm and Peachtree Creek to the list of battlefields on which they had bled. At the end of July, Williams wrote that his division “has been sadly cut up, so that I am reduced in numbers to a brigade.” After months on the move under almost constant fire, the old general uncharacteristically felt “debilitated and broken down.” But duty called, and, as the Union army readied for the push on the fortified outskirts of Atlanta, Maj. Gen. Hooker resigned his command. Once again, Williams took command of the corps.

Much to Williams’ liking, Maj. Gen. Slocum assumed command of the Twentieth Corps at the end of August. A few days later, federal artillery won out against Atlanta’s defenses. During the night of September 1, Williams awoke, “from a dream of heavy thunder in which the earth seemed to tremble.” The Confederates had blown up their ordnance stores before evacuating the city. The next day, Williams and his division were among the first to enter Atlanta, with bands playing and the Stars and Stripes flying.

Williams spent his first night in the fallen Confederate city in a private home, sleeping in a real bed for the first time in months. He found it impossible to sleep in the oppressive inside air however, and returned to his tent the next evening. In the ensuing days of relative quiet, he found himself reflecting on the war in letters home, lamenting that, “three years have taught me sad lessons of sudden and painful partings and of friendships swept away by hundreds in an hour of bloody battle.”

Sumter Avenged

With Atlanta captured, Sherman set his aim on Savannah. His 60,000-man army cut telegraph lines to the outside world on November 15, and embarked on what Williams called a “promenade militaire.” Again in charge of the corps, with Slocum manning the left wing of Sherman’s column, Williams directed his men to rip up 70 miles of rail line, and plunder the surrounding countryside. In the summer of 1862, Williams had felt all that was needed was “kindness and gentleness to make all these people return to Union love.” Three years of savage fighting seemed to have changed his opinion.

Sherman’s forces arrived in Savannah on December 21. As Lincoln learned of Sherman’s success, Williams received a promotion to brevet major general. He sewed the extra star on his collar. But he was unimpressed by the symbolic accolade.

The corps set off again in late January 1865 for Columbia, S.C., redoubling their efforts to bring the pains of war to the Southern populace. “We swept through South Carolina, the fountain-head of the rebellion, in a broad, semicircular belt, sixty miles wide,” Williams recalled. “Our ‘bummers,’ the dare-devils and reckless of the army, put the flames to everything and we marched with thousands of columns of smoke marking the line of each corps. The sights at times, as seen from elevated ground, were often terribly sublime and grand; often intensely painful from the distressed and frightened condition of the old men and women and children left behind.”

In a later letter, he concluded, “The first gun on Sumter was well avenged.”

The Final Push

After Columbia, Sherman wasted no time marching north. Having faced minor resistance in South Carolina, the campaign in North Carolina proved more difficult. Sherman’s army engaged at Averysboro on March 16, and then again on March 19, when a small but determined force under Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston attacked Slocum’s wing of the march near Bentonville. The brunt of the well-executed attack fell on the Fourteenth Corps. With the help of Williams and the Twentieth Corps, the Fourteenth regained its footing. Reinforcements came up, and a greatly outnumbered Johnston resumed his retrograde motion. It was Williams’ last battle.

A week later, near Goldsboro, Williams again returned to divisional command, usurped this time by Maj. Gen. Joseph A. Mower. Williams estimated it was “about the fortieth time,” that he had “been foisted up by seniority to be let down by rank!”

On April 6, news arrived that Richmond had fallen. On the April 9, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Sherman continued to Raleigh, encountering half-hearted skirmishing, and pushing Johnston’s army in his path. News arrived of Lincoln’s assassination shortly thereafter. “I have never seen so many joyful countenances so soon turned to sadness,” Williams bemoaned, adding that he feared Lincoln’s death would “complicate matters.”

Days later, on April 29, as the Twentieth Corps waited in Raleigh, Williams dashed off a short letter to his daughters. “Johnston has surrendered his whole army east of the Chattahoochee River. … Tomorrow we march toward Richmond and Alexandria. … The newspapers will give you terms of the surrender before this reaches you.”

The war was over.

Going Home, New Assignments

Sherman’s army concluded its campaign through the South as it had started—on foot. Though the guns had fallen silent, the boots trod on. The army made the 170 miles to Richmond in nine days, arriving in an overcrowded Alexandria, Va., on May 21, just in time for the Grand Review. Buttons were polished, uniforms replaced, and, more than likely, Old Pap procured a new hat.

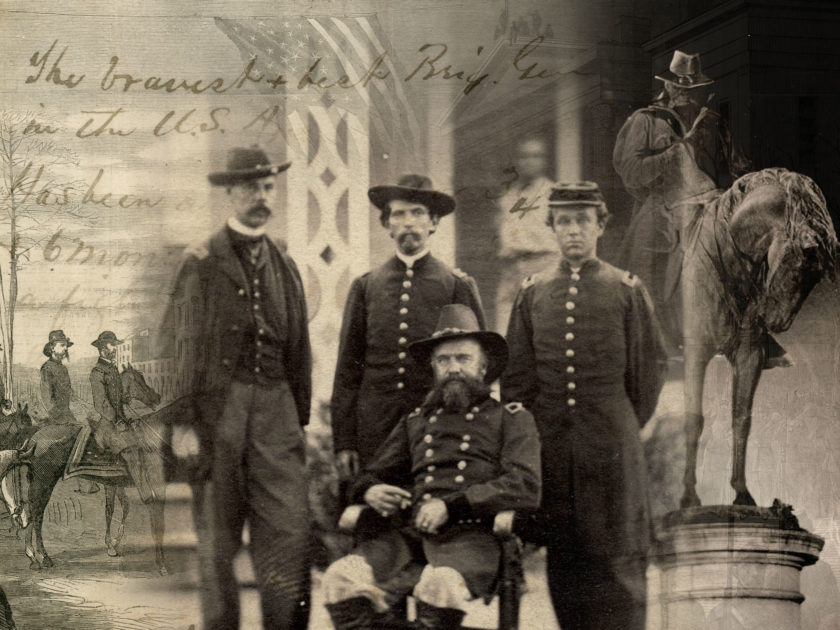

Williams received armfuls of bouquets at the Grand Review, along with numerous compliments from acquaintances and the press. The New York Herald proclaimed that the “Red Star” division, in Williams’ words, “took the palm.”

One might have assumed after four years of fighting Williams would welcome a rest. Instead, while his regiments slowly trickled home over the summer, he accepted an assignment overseeing a military district in Arkansas until January 1866. When his duties finally concluded, he returned to Detroit, still, and forever, a brevet major general.

Williams remained in Detroit for barely eight months. Without an occupation and with limited funds after four and a half years away at war, he accepted a position as the U.S. resident in El Salvador, remaining until late 1869. He returned to Michigan and unsuccessfully ran on the Democratic ticket for governor. He was elected to Congress in 1874 and again in 1876. He also remarried in 1875 to the widow of a well-known Detroit merchant.

Much as he had in all of his many walks in life, Representative Williams earned a reputation for integrity and level headedness. He continued to resist “puffering,” and spoke only when he felt it warranted. His skills were put to use on the Committee on Military Affairs and, in his second term, overseeing the Committee for the District of Columbia. After a meeting for the latter committee on Dec. 21, 1878, Old Pap returned to his office and suffered a stroke, dying at his last post.

Unwritten History

Williams had been correct that his modesty with the press and peers, along with his lack of West Point education and age, kept him from assuming higher command. If he realized his personal politics added to the equation, he never recorded it. His affiliation as a lifelong Democrat, especially early in the war, made it impossible to win favor in a promotional system which prioritized political gain. Williams had few political connections, few friends in Congress at the time (the vast majority of Michigan’s senators and representatives were Republicans), and certainly not the popularity to swing votes on the home front needed to wage war.

Though a diligent and effective commander, Williams either lacked the skill or the opportunity to swing the outcomes of major battles in a way that propelled him past the reasons that held him back in rank. Therefore, Williams remained a brigadier.

With the benefit of historical hindsight, it can be reasoned that Williams was exactly where he was needed. His dependable leadership contributed to Union victories—or at least less drastic Union defeats—at critical battles that spanned the entire war.

Years after Williams’ death, a statue to his memory was erected on Belle Isle in Detroit. Old Pap, mounted on Plug Ugly, still stands there amidst the bustle of modern life, with few passersby realizing the significance of the man whose shadow they cross. The most tragic consequence of Williams’ lack of self-promotion he could not have foreseen, but it ensured that he, along with his men, would fall through the cracks of time. The historical record often glosses over Williams’ military service, or excludes it entirely. His detailed correspondence remain the shining exception, accessible to anyone in Milo Quaife’s From the Cannon’s Mouth.

“There is an unwritten history of these battles that somebody will be obliged to set right some day,” Williams penned in the summer of 1862.

Perhaps the time has come to do just that.

Ben Myers is a web developer residing just outside Washington, D.C. His first book, American Citizen: The Civil War writings of Captain George A. Brooks, 46th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (Sunbury Press) will be released within the next year.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.