By Kurt Luther

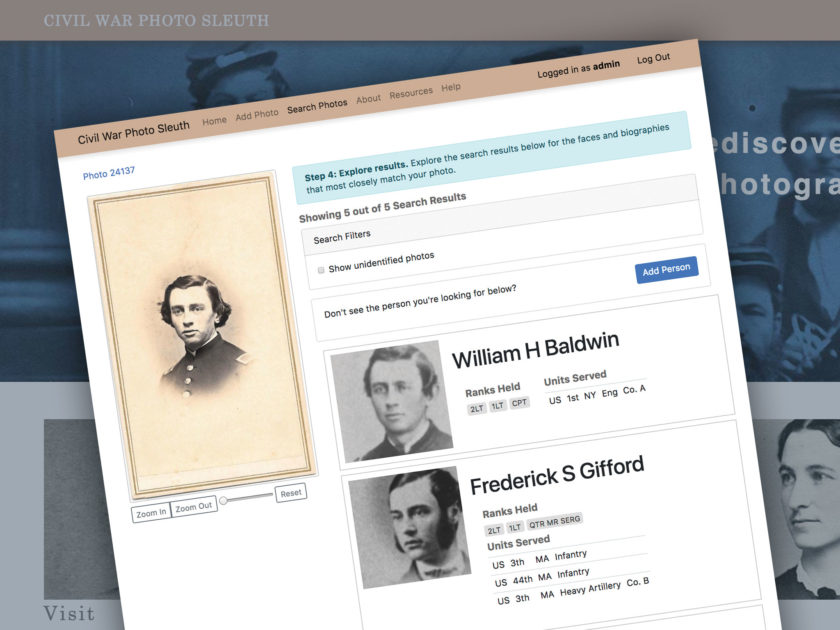

Last August, we launched Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS), a free website that brings together community expertise and face recognition technology to identify unknown Civil War soldier portraits. I wrote about the launch of that software in the Autumn 2018 issue of MI. In this column, I want to provide an update on how the site has been used since then, and our plans for the future.

We wanted to understand what worked well, and what could be improved with the CWPS site. So a group of students—Vikram Mohanty, David Thames, and Sneha Mehta—and I conducted a survey of the first month of usage, from Aug. 1, 2018 to Sept. 1, 2018. We looked at three main sources of data. First, we crunched the raw numbers for overall site usage: how many people signed up, how many photos they added, and so on. Second, we ran a more focused analysis of user-identified photos. And third, we did hour-long phone interviews with nine of the most active users of CWPS, asking them how they used to do Civil War photo sleuthing, how the site may have changed the ways they work, and what they liked and disliked about it.

We organized our study results around three user activities: creating accounts, adding photos to the site, and identifying unknown photos.

Creating Accounts

CWPS user accounts are completely free. But you are required to register one in order to add, identify, or tag photos. Unregistered users can only view or search for existing photos in the database.

We found that 612 people registered accounts on CWPS during the first month. More than half of these came in the first three days, thanks in part to our launch event at the National Archives Building, and a burst of publicity from MI, the American Battlefield Trust, the Center for Civil War Photography, and other supporters. Afterwards, the site saw steady growth of about five-to-10 new accounts each day.

Adding Photos

These users added 2,012 photos to the site in the first month, of which over 900 came in the first three days. Following this, users added an average of 30 photos per day.

About one in every three users who signed up added at least one photo. The average user contributed about 13 photos, but three of the most active users contributed more than 200 photos each.

Approximately 80 percent of the photos added were front views. But there were still 380 cases where users added back views, too. Since many popular photo archives like the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) and the MOLLUS collection do not include back views, CWPS promises to become a unique source of reference materials.

About half of the uploaded photos were unidentified, with the rest either fully (about 40 percent) or partially (about 10 percent) identified. Although it is optional for users to explain where they learned the identity of a photo (e.g., from an inscription), we were surprised that users voluntarily provided this information in all but 36 cases.

Why did users voluntarily spend their time adding photos, especially ones whose identities were already known? In subsequent interviews, they gave a variety of motivations. Many of them centered on giving back or helping others. On the other hand, some interviewees chose not to add certain photos because of concerns about bootlegging or being reshared without permission.

Identifying Photos

Of the 560 identified photos added by users, 441 already had known identities, while 119 were newly identified using the website. These newly identified photos mapped onto 88 unique soldier identities because some users had multiple photos of the same soldier.

CWPS allows any user to identify an unknown photo, so we wanted to get a sense for how accurate these identifications tended to be. We carefully reviewed the 88 soldier identifications and rated each one as positive (possibly or definitely correct) or negative (probably or definitely wrong).

More than 85 percent of the identifications were positive. Looking closer, we noticed several patterns. Thirty of the IDs were what we called “replicas,” meaning the unknown photo matched to an identical, identified view in the reference database. They were more common for cartes de visite, where multiple copies of the same view could be in circulation, compared to hard images, which were unique. Replica-based IDs are the easiest to confirm, and indeed, all 30 we reviewed were positive.

On the other hand, there were 37 identifications in the category we considered most difficult, where the mystery photo matched to a different view of a soldier, and without a supporting inscription. In these cases, users had to use their best judgement to decide if two similar-looking soldiers were actually the same person. We found that 25 of these were positive identifications, while 12 were negative. Thus, CWPS users made good decisions for the majority of identifications in the most difficult category, but also made some false connections.

Our users’ expertise and the face recognition technology provided complementary strengths. While automated face recognition can offer a powerful tool for narrowing possibilities, it is far from perfect, and users often found themselves digging deeper. In fact, there were 30 cases where the matched photo was not the most similar face, and sometimes not even among the top 50 most similar faces. Users told us in interviews that the face recognition technology struggles with profile (side) views, and ignores important facial clues like ear lobes and hairstyles. These findings support our choice to design CWPS so that the software itself never identifies a photo, but rather requires users to make the final decision.

Interviewees shared many stories of making successful identifications, including some they doubted they would have ever found without the site. Others expressed a desire to keep some discoveries private. For example, a collector identified an unknown photo for sale online, but decided not to publicly share the ID to avoid a bidding war. These perspectives speak to broader questions raised by CWPS about the tensions between benefiting the individual versus the public.

Current Status and Future Plans

Since we analyzed the first month of usage, CWPS has grown significantly, accompanied by a burst of media coverage in late 2018 by online publications, such as Slate, Smithsonian, and Family Tree. Today, the site has topped 25,000 photos, of which over 4,000 registered users have contributed more than 8,000.

We continue to give presentations to spread the word about CWPS. Ron Coddington and I demonstrated the site to an enthusiastic crowd at the Center for Civil War Photography’s 14th Annual Image of War Seminar in October 2018. This year, I will give additional talks at the Intelligent User Interfaces conference in Los Angeles, Calif., and the grand opening of the expanded American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va.

Finally, our team is working hard to make the site more powerful and easier to use. Building on last summer’s successful internship program, we have hired several more students to help with software development, community management and historical research. A priority for this year includes improving our response rate to user questions, suggestions, and problem reports. On the software front, we are exploring a “second opinion” feature, inspired by examples in Civil War Faces and other online discussion groups, to aid users with gathering feedback from their social network about whether a proposed soldier identification is correct or not.

The key to the success of CWPS remains the strength of our community. We remain deeply grateful for your interest and contributions thus far, and hope you will continue to share your ideas, concerns, and, of course, your amazing Civil War photos.

We welcome your feedback on CivilWarPhotoSleuth.com, either via email or by submitting the feedback form on CWPS. We will continue to make regular updates and improvements, announced through our Facebook page and elsewhere.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.

© Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.