By Daniel R. Glenn

The men of the 14th New York Infantry lay on the ground near Gaines’ Mill, Va., on June 27, 1862, unsure of what to expect. Suddenly, the woods erupted with the sharp cracks of small arms, illuminating the tree line with flashes of rebel muskets. Soon the Confederates were upon them, charging rank by rank.

At one point during the action, according to an historical sketch of the regiment, “the colors of the 14th appeared to waver, and the column to be in danger of breaking.” The colonel, James McQuade, “rushed forward, seized the colors, and, waiving them aloft, exclaimed ‘Rally on the colors, men, I’ll stand by you to the last!’ The effect was magical; every man planted him-self firmly in line, and there was no more wavering that day.”

After successfully repelling two attacks, the Union line began to fall back and reinforcements covered the retreat. The exhausted New Yorkers found refuge and waited for orders.

Among the fatigued men of the 14th was Pvt. Almon C. Barnard. Like many of his comrades, he was about to endure a long and arduous night. Later, when a fresh wave of Confederate troops drove the New Yorkers back a second time, Barnard “came out missing my hat and one shoe,” he wrote to his mother and sister on July 22 in a letter summing up his battle experiences.

The 14th then received orders to defend Union artillery, noted Barnard in his letter “if it cost every man in the brigade.” During the action that ensued, Barnard heard the sound of an incoming shell and dove to the ground. The projectile whizzed past his left ear and exploded about 20 feet away. With his ears ringing, but otherwise unscathed, Barnard “hardly knew what had happened,” writing, “All was confusion.” His symptoms suggest he had suffered a concussion. By the early hours of June 28, the 14th and the rest of Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s Fifth Corps were in full retreat.

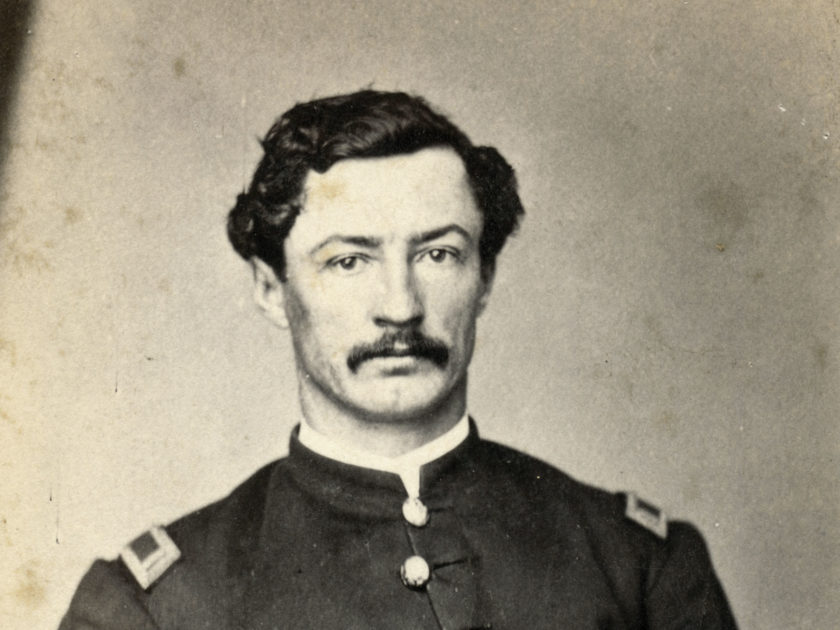

The engagement, part of the failed Peninsula Campaign, was one of Barnard’s earliest combat experiences during his four years of military service in the infantry, artillery and cavalry. Born and raised in Genesee County, N.Y., Barnard mustered in as a second sergeant in the 14th New York Infantry in May 1861. Soon afterwards, his regiment escorted the remains of the late Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth through the streets of Albany. Ellsworth, a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln who had been shot and killed as he attempted to haul down a Confederate flag from its perch atop an inn in Alexandria, Va., became a martyr across the North. Barnard recalled the crowd’s outraged cry for “revenge for the murder of Elsworth.”

On their way to Washington in late June, Barnard and his comrades passed through Baltimore. Just two months earlier, the city erupted in violence when pro-secession rioters attacked federal soldiers from the 6th Massachusetts Infantry. The New Englanders suffered numerous casualties during their cross-town march to board a train for the Union capital.

The 14th approached Baltimore warily. “We were ready for them,” Barnard wrote to his sister on June 23. Although the streets were “covered in people … all was as silent as if there were no one in the streets,” he wrote, and the men marched through the city facing nothing but “scouling brows.”

Upon arriving in Washington, Barnard had the chance to rest in “old Abe’s gardin” outside of the White House. Soon, word of the battle at Bull Run reached the city, and from his post near Georgetown, Barnard witnessed a line of Union troops retreating from the defeat “with arms shot-off” and “a number of bullets holes in their cloaths.”

Meanwhile, Barnard had fallen afoul of his superior officer, Lt. Robert H. Foote. Their troubles came to a climax in October 1861, when Foote stripped Barnard of his sergeant’s chevrons after he missed a drill.

The following spring, during the early part of the Peninsula Campaign, Barnard, now reduced to the ranks, had his first encounter with enemy artillery as he constructed fortifications during the Siege of Yorktown. He wrote home in a letter on April 28, 1862 that, “Mr big gun from the Secesh fort kept a throwing their missels at us.” Nearby, an incoming shell narrowly missed Maj. Gen. Porter. Barnard mused, “I wonder if that ball was for me.”

While near West Point, Va., on May 7, 1862, Barnard helped bury the bodies of those who had died in an amphibious assault on Eltham’s Landing. Many of the dead, he observed, had “their throats cut from ear to ear.” Other Union soldiers also took note of the brutality. Barnard, furious at what appeared to be a dastardly deed committed by Confederates against the men after they surrendered, promised to “give no quarter nor ask none … they have commenced it, and we will end it.”

On May 27, the 14th had its own “turn with the Rebs” at Hanover Court House, Va. After a day of heavy rain, Barnard’s regiment marched against the Confederates, hampered by knee-deep mud in some places on the battlefield. Barnard’s company was tasked with picking up casualties as the rest of the regiment pursued the retreating Confederates. “The dead and wounded lay as thick as they could along their whole line,” he recalled. “I tell you we sent the balls over there so fast and thick that the poor rebs could not get one in edgewise.”

The regiment was truly put to the test during the brutal Seven Days Battles in June and July 1862. Barnard’s narrow miss with the shell at Gaines’ Mill was not his last close call. Four days later at Malvern Hill, the regiment faced off with the rebels again. In a letter home dated July 6, he explained to his sister, “I am alive yet, although wounded slightly, in the left arm a piece of shell bruised my arm and a buck ball went into the fleshy party of the same member. But I got it out all right and it is doing well.” He was one of the lucky ones—106 of his comrades were listed as casualties after the Union victory.

Barnard was impressed with the enemy. “I can say for them, they are brave soldiers, for when our artillery and musketry mowed them down, and piled them up in heaps, they would not flinch, but close up their ranks and keep on till their bayonets touched ours, but there we were always too much for them,” he observed in his July 6 letter. He added, “Our Brigade have lost two thirds of their numbers in killed wounded and missing, and have been reported unfit for duty. I dont know what they will do with us. One thing is sure, they can’t put us into many more battles.”

He was wrong. Barnard would see plenty more fighting before the end of 1862—at Second Bull Run in August and at Fredericksburg in December.

His Fredericksburg experience was similar to those of other federal soldiers. He explained in a letter home how they “drove the Rebs back to their entrenchments but we could not budge them an other inch,” adding, “in fact we found that their position was impregnable.” Barnard’s regiment slept on the battlefield that cold, winter night amidst thousands of casualties. “The dead and wounded lay thick all around us, and their groans, and cryes for help, was piteous in the extreme. … It is nothing that 10000 Union soldiers are slaughtered if it satisfies the cry of the north for a winter campaign.”

When his term of enlistment expired in the middle of 1863, Barnard mustered out of the army and returned to his family, who had recently moved from New York to Pittsford, Mich., a community southwest of Detroit.

Barnard rejoined the army in September 1863 as a first sergeant in the 11th Michigan Cavalry. Two months later, he wed a young lady named Harriet Breese. Barnard married her in secret and “on short aquaintence” because he wanted her to have marriage papers to support her in any future financial claims, should he die in the war.

His plan became moot when, in April 1864, Hattie died of measles. Barnard was devastated. “I hope it is my lot to fall fighting in this war,” he wrote to a sister, “that I shall be good enough to meet her wher she has gon, for there is not another like her.”

In July 1864, Barnard passed an examination to become an officer in the U.S. Colored Troops, and was eventually assigned as a first lieutenant to the 12th Heavy Artillery. His writings indicate no interest in furthering the cause of abolition. He did note, however, that he was “sick of the cav.” Like many white soldiers, promotion and higher pay were likely motivations.

After he received his commission, Barnard wrote that he and other officers began “collecting niggars for the service.” He found that “collored troops are very easy to manage … they have always been slaves and they take a great deal of pride in soldering.”

“The dead and wounded lay thick all around us, and their groans, and cryes for help, was piteous in the extreme.”

Barnard’s stint in the 12th lasted until the spring of 1866. He spent much of it on garrison duty in war-torn Kentucky. He was granted a leave of absence in September 1865, to marry Hattie’s sister, Emma Breese, in Kalamazoo, Mich.

Barnard mustered out of the service on April 24, 1866, and returned to his new bride. He worked as a farmer and performed odd jobs to support her and a family, which grew to include four children. Emma divorced him in 1886, however, for unknown reasons. Ten years later, Barnard married Sarah Ann Sirrine, and the couple settled in Petoskey, a town in northern Michigan.

During his late years, Barnard’s hearing steadily declined, which he attributed in part to the shell concussion that had injured him at Gaines’ Mill. His deafness became a constant frustration for him, one that “shuts me out of any vocation other than that of farming,” he wrote in 1891. “People do not want to be bothered with a deaf man.” He suffered with this condition until his death in 1907, at age 68.

Dick Tanner, the owner of photographs, letters and other papers that belonged to Barnard, gives special thanks to Jim Quinlan of The Excelsior Brigade for his assistance and support.

References: Almon C. Barnard military service record and pension files, National Archives; Third Annual Report of The Bureau of Military Statistics, State of New York; Almon C. Barnard Papers, Dick Tanner Collection; Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers in the Civil War, 1861-1865; Marriage certificate of Hattie M. Breese and Almon C. Barnard, State of Michigan; True Northerner (Paw Paw, Mich.), May 20, 1886; Almon C. Barnard Death Certificate, State of Michigan.

Daniel R. Glenn is a student at Christopher Newport University majoring in American Studies and political science. He plans to attend law school.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.