By Kurt Luther

Photo sleuthing fundamentally pieces together bits of evidence to build a theory. For especially tricky images, these pieces of the puzzle may come from a wide variety of sources beyond major photo archives, reference books and online databases. In this column, I will give an example where these usual suspects get us partway to our goal, but casting a wider net—including period newspapers, wartime letters and a photo from a century later—provides the critical details to identify a group of soldiers. These, plus a generous helping of serendipity.

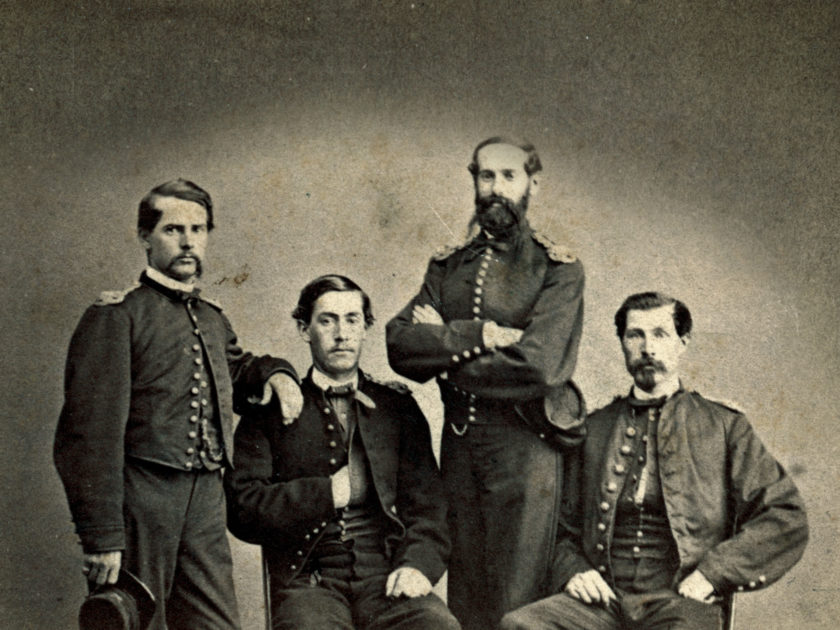

I received as a gift a carte de visite depicting four unarmed Union officers. All wore short jackets with a row of many buttons and the distinctive Russian shoulder knots of Union artillery officers. Although Russian knots can display rank insignia, none was visible to my eye. Two men grasped the brims of kepis, one revealing the crossed cannons insignia of an artillerist, the other, showing officer’s braiding of indeterminate rank. The men wear four different styles of facial hair, from clean-shaven to full-beard, and they strike four distinct poses, including the Napoleonic hand-in-waistcoat gesture.

The back of the carte included a photographer’s mark by Oliver H. Willard of Philadelphia, known for his 1866 photo series of Union Army uniforms and accoutrements commissioned by Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. The absence of a tax stamp suggests the photo predates August 1864.

Perhaps the most striking clue is the inscription penciled on the back in a modern hand:

“CHARLIE”, “TOM”, CAPT. EATON, LIEUT MOORE

CAMP BARRY

WASHINGTON D.C.

CAPT JOHN B EATON

NEW YORK LIGHT, 27TH BATTERY

It looks like a kindly researcher had not only provided the location and the unit, but also a name for each officer. At first glance, it might appear that there is not much left for us photo sleuths to do here. But as we showed in the Summer 2016 edition of this column, photo inscriptions can be invaluable clues, but they often leave out critical details, requiring substantial research to fill the gaps.

In fact, in the January/February 2001 issue of MI, a copy of this view appears in an article on Union rank insignia by Mike Fitzpatrick. (Slight variations reveal it is not the same one as in my collection.) This version, credited to the collection of Don Wisnoski via David Sullivan, includes the caption:

Officers of the 27th New York Light Artillery, identified from left as “‘Charlie,’ ‘Tom,’ Capt. Eaton, Lieut Moore, Camp Berry[sic], Washington, DC, 1863.”

This caption reiterates the soldiers’ names, but also adds two intriguing details. First, it suggests the names map onto the subjects in sequence, left to right. Second, it gives a date for the photo: 1863.

As promising as these clues seemed, I did not want to take any at face value. My plan was to first verify the most specific details in the inscription, namely, the identities of Capt. Eaton and Lt. Moore. If those details checked out, then I would work backwards to identify the sketchier “Charlie” and “Tom.”

This plan soon changed, however. It was not hard to track down military records for Capt. John Brown Eaton, who commanded the 27th New York Independent Battery for its entire existence, spanning late 1862 to the summer of 1865. But none of the usual suspects—MOLLUS, the American Civil War Research Database (HDS), the New York State Military Museum, or even the Hail Mary of Google Image Search—yielded even a single wartime portrait. This was a rather surprising and disappointing turn of events for a Union battery commander who, by all accounts, served for nearly three years with distinction. Yet, the 27th—also known as Eaton’s Battery and the Buffalo Light Battery—was a small unit, and only a handful of photos of its modest membership seem to have survived.

I was not quite ready to give up on a photo of Eaton. With the help of Newspapers.com, I meticulously searched through several decades of 19th century archives from the Buffalo region, where the 27th was mostly recruited. In the Jan. 8, 1893, edition of The Illustrated Buffalo Express, I found a full-page profile on Eaton, who, after more than 25 years as a career army officer, finally achieved the rank of captain he had held as a volunteer in the Civil War, along with a quartermaster’s posting in the nation’s capital. Less than a year later, he would be dead from heart disease and interred in Buffalo’s Forest Lawn Cemetery with many of his subordinates from the 27th.

True to its name, the Illustrated Buffalo Express article was illuminated with two large photos of Eaton. Unfortunately, the microfilm (or scanning job) was of such poor quality that it rendered both the wartime profile view of Eaton and his more recent postwar vignette, bearded and festooned with aiguilettes, almost indistinguishable. (I am still trying to locate a better copy.)

With Eaton’s photo at a dead end, I turned to the second-most inscribed man in the photo, “Lieut Moore.” A records search showed only one officer named Moore in the 27th: Peter L. Moore, who enlisted as a first sergeant when the battery formed. Moore worked his way up to second lieutenant in January 1863 and “won his straps by sheer merit alone,” according to the Buffalo Evening Post. There were however, some bumps in the road. In December 1863, he was deemed a “supernumerary officer” and sent back to Buffalo to run the recruiting office with a couple of “staff.” It is unclear if he ever took the field again, but in spring 1865, he was promoted to first lieutenant and served in Washington, D.C., until the war’s end.

Happily, Lt. Moore’s HDS profile includes a wartime photo, courtesy of the Kiowa County Historical Society. In this bust view, he wears his well-earned second lieutenant’s shoulder straps (notably, not Russian knots) and a slightly fuller goatee, but otherwise matches the man seated at the far right of our mystery group photo. Having identified “Lieut Moore” as Lt. Peter L. Moore of the 27th, I now had reason to believe the inscription was not completely off base. My next step was to try to identify the remaining two officers.

To accomplish this, I decided to create a concurrent service timeline, as described in the Autumn 2016 edition of this column, which rests on the assumption that larger group portraits, especially of officers, tend to be members of the same unit. My prior research suggested that the photo probably shows Capt. Eaton, Lt. Moore, and two officers who served with the 27th between July and December 1863, when the battery was based in Philadelphia. Conveniently, this time window aligns with the 1863 date on the Wisnoski carte.

Using the rosters published by the New York State Adjutant General Office around the turn of the 20th century, I built the concurrent service timeline. New York’s rosters provide wonderful details to support this process. For example, they differentiate between date of rank and effective date, they indicate which officer first held a rank in that unit (“original”), and they indicate who a promoted officer replaced (Latin vice, for “in place of”). Given these latter details, I opted to build the timeline based on ranks or billets, rather than soldiers.

The concurrent service timeline showed that, while about half a dozen men served as officers of the 27th at some point in the war, only two served with Eaton and Moore between July and December 1863. One of these officers was 1st Lt. Charles A. Clark, who stayed with the battery until early 1865, when he received the captaincy of the 12th New York Independent Battery. It is not much of a stretch to conclude that Lt. Clark went by the nickname “Charlie,” at least to the anonymous author of the carte’s inscription.

My timeline showed that the second officer who served with Eaton and Moore (and Clark) was 2nd Lt. Orville Smith Dewey. For Dewey, the 27th was one stop on a Civil War tour of duty that included two infantry regiments, two light artillery batteries, a wounding at Antietam, and promotions from private to first lieutenant. After the war, he served in the 4th U.S. Cavalry, but succumbed to yellow fever in New Orleans in 1867. Dewey and Clark reside with Eaton at Forest Lawn Cemetery.

The only problem with Orville Smith Dewey is that his name was Orville Smith Dewey. I double-checked my timeline, but it was intransigent: Dewey was the only officer who served with Eaton, Moore, and Clark.

Who, then, was “Tom,” our final unidentified man? I looked through all 294 men who served in the 27th for anyone with a first or middle name variant of Tom. The only three hits—Thomas Costello, Lewcock and Price—never ranked above corporal, and would not have worn Russian knots. If Tom was not even a member of the 27th, I doubted I would ever find him. And, if the group shot contained one outsider, then it could contain two, and “Charlie” could be anyone. My carefully constructed theory about this group photo faced a danger of falling apart.

Aside from his name, Dewey still struck me as the best candidate for the final officer. I thought back to my failed attempt to locate a photo of Capt. Eaton, and wondered if I might have better luck with Dewey. I began searching online databases for any trace of Dewey. I did not find any photos, but in the digitized archives of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, I stumbled across something much better: a collection of Dewey’s wartime letters. Reading the opening line of the item description, I blinked:

Nicknamed “Tom” by his family and coming from Buffalo, Dewey served in the army of the Potomac, primarily in Washington at an instructional camp.

Orville Smith Dewey is “Tom,” after all.

Serendipity gets most of the credit for this one. But that did not make the result any less satisfying. All four soldiers had been identified, and every piece of the puzzle lined up. The aforementioned “camp of instruction” was Camp Barry, named for Maj. Gen. William Farquhar Barry, on whose staff Dewey served at one point (and who is also buried at Forest Lawn). The 27th spent the first half of 1863 there, and then removed for the rest of the year to Philadelphia, where evidence suggests the battery’s four officers sat for Mr. Willard’s group portrait. More than a century and a half later, we can reconstruct that moment and identify the men behind their nicknames. The inscription from the Wisnoski copy suggests the names identify the photo’s subjects from left to right, but this claim, like the rest of the inscription, deserves confirmation.

Serendipity led to one other discovery. While searching for information about Capt. Eaton in the Digital Public Library of America, I found a recently digitized photo from a 1961 issue of the Valley Times, a California daily newspaper. In the photo, a Mrs. Anne Donnelly proudly displays her “treasured possession,” purchased for $50: a photo album of “faces and scenes in war and peace” collected by none other than Eaton himself. “Eaton’s face,” the caption continues, “along with hundreds of his wartime comrades and commanders, appears numerous times in the thick, age-worn picture album.” Eaton is described as “a bearded young captain,” supporting our assumption that he is the sole bearded officer in the group photo.

I have not yet been able to locate this photographic goldmine, but I sincerely hope it survives. Perhaps some lucky photo sleuth will track it down, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.

We encourage you to submit other photo mysteries to be investigated as well as summaries of your best success stories to MI via email. Please also check out our Facebook page, Civil War Photo Sleuth, to continue the discussion online.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He writes and speaks about ways that technology can support historical research, education and preservation.

© Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.