By Ronald S. Coddington

The sturdy paddle wheels of the Star of the West beat rhythmically against the waters of the Atlantic, as she steamed into Charleston Harbor. Packed with supplies and reinforcements for the beleaguered federal garrison holed up inside Fort Sumter, she entered the main shipping channel early on Jan. 9, 1861.

Her every move was watched onshore by a contingent of local militia companies and other volunteers. The men manned coastal batteries and Fort Moultrie in defense of the newly independent Republic of South Carolina—and in defiance of the Union.

One volunteer on the rolls of Fort Moultrie, Jack Grimball, had, up until recently, been a Union navy officer. He had acted decisively after South Carolina seceded from the United States on Dec. 20, 1860. On Christmas Eve, he resigned his commission and tendered his services to the governor. The Charleston Courier praised him: “Nothing less can be expected of true sons of the South.”

Grimball was also true to his family in Charleston. One of six boys born to a well-to-do planter and his wife, John Grimball was known as ‘Jack’ or ‘Johnnie’ to friends and relatives. He left home in 1854 at age 14 to attend the U.S. Naval Academy. After graduating in 1858, he embarked on a career in the navy. Any dreams he might have had of fame and glory in blue was dashed after South Carolina seceded. He was among the first U.S. Navy officers from the South to resign. Many of Grimball’s peers followed his lead in the months ahead, as the Southern states withdrew from the Union. Four of his brothers would also serve in the cause as soldiers in the infantry and artillery.

Grimball’s first assignment as a Confederate was in the garrison of Fort Moultrie, which had been occupied by federals. On Dec. 26, 1860, garrison commander Maj. Robert Anderson moved his men to nearby Fort Sumter. The brick fortress in the center of Charleston Harbor offered better opportunities for defense.

Meanwhile in Washington, outgoing President James Buchanan dispatched the Star of the West, with a cargo of supplies and reinforcements for Anderson and his regulars. The steamer, an unarmed civilian merchant vessel out of New York, was selected rather than a warship, so as not to fan the flames of rebellion.

News of the mission spread to Charleston, and the ship’s approach was interpreted as an act of aggression by a foreign power. When the Star of the West arrived in the harbor on Jan. 9, Grimball and the rest of the state forces, including cadets from the Citadel, met her about daybreak. Following a warning shot from shore, the Star of the West increased her speed and hoisted the Stars and Stripes. A flurry of artillery blasts followed. “As soon as five or six shots had been fired upon her from Morris Island, and as many more from Moultrie, it was evident that she would lower her colors to half-mast. She veered about so as to avoid any further messengers of this kind from the fortifications, which with one or two more discharges, finally ceased,” reported the Charleston Courier.

Seventeen shots were fired, with two striking the hull of the Star of the West. Though the damage was minor, the effect was major. The ship turned about, and steamed back to the North, without having accomplished its objective.

South Carolina declared the confrontation a victory. Some authorities claimed that these were the first shots fired in hostility during the Civil War. Others discounted the assertion, because the Star of the West was technically a civilian vessel. In any event, the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, has long been acknowledged as the official start of the Civil War.

A few days later, Grimball was commissioned a midshipman in the new Confederate navy. Thus began an odyssey during which he served on several notable vessels. His first assignment aboard a converted merchant steamer, commissioned the Lady Davis in honor of the wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, defended Charleston Harbor during the early months of the war.

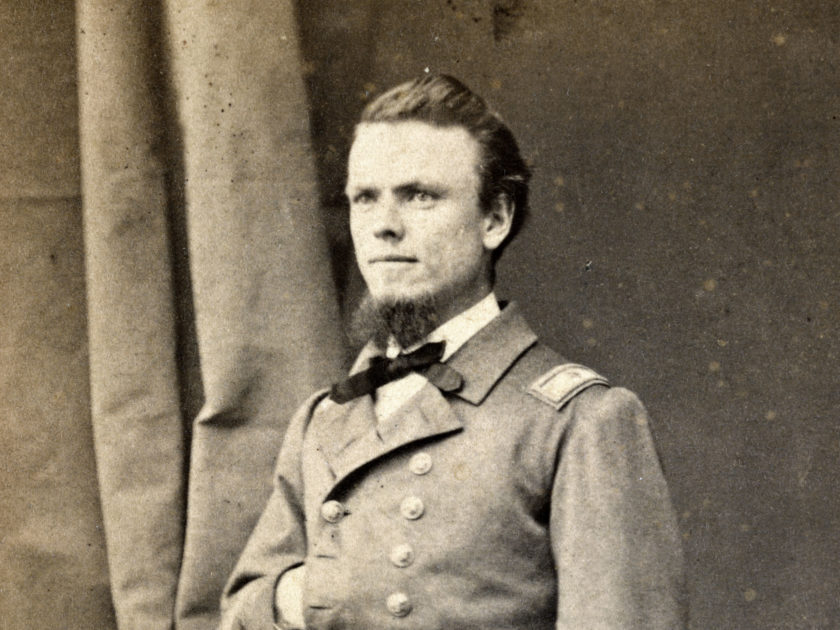

Grimball advanced to first lieutenant, and in 1862 joined the crew of the ironclad Arkansas. On July 15, he commanded one of her bow guns during a successful run past the Union fleet assembled above Vicksburg, Miss. Following the loss of the Arkansas in August 1862, Grimball served a short stint on the ironclad ram Baltic in Mobile Bay, before being called to special duty in Europe. He posed for his carte de visite portrait in a Paris photography salon about 1864.

Later that year, he reported for duty on the Shenandoah. Grimball and his shipmates hunted Yankee merchant ships on the high seas during a yearlong cruise. Their exploits inspired other Southerners during the waning months of the Confederate nation, and prompted Northerners to brand them pirates. The Shenandoah continued to operate for months after the surrender of the gray armies and the dissolution of the government. The crew had heard rumors of the downfall of the Confederacy, but had not received any confirmation of the South’s demise.

“We were now the only Confederate cruiser afloat, and as we continued our course around the world, passing from ocean to ocean, meeting in turn ships of various nationalities, I always felt that whenever our nationality was known to neutral ships the greetings we received rarely warmed up beyond that of a more or less interested curiosity, and while we had many friends ashore who were most lavish and generous in welcoming us to port, underlying it all there appeared to exist a wish of the authorities to have us ‘move on,’” Grimball stated.

The cruise of the Shenandoah finally ended on Nov. 6, 1865, when the vessel was surrendered to British authorities. Grimball and other officers were promptly released from captivity. Aware of rumors that they would be arrested as pirates and likely face the hangman’s noose if they stepped foot on American soil, Grimball and his fellow officers fled to other countries.

The rumors proved false. Grimball spent a year on a ranch in Mexico, and then returned to his family in South Carolina. By this time, he decided to abandon the sea, and, with the aid of his father, studied law, and became an attorney. Grimball practiced in Charleston for a short time, and then established a firm with a partner in New York City. In the early 1880s, “His heart turned toward Charleston and he came back,” reported a state historian. In 1885, at age 44, he wed Mary Georgianna Barnwell, a belle half his age. They started a family that grew to include four sons. The marriage was Grimball’s second: The first, in 1875, ended tragically after less than a year, when his bride died of disease.

Grimball was best known during his later years for his service on the Shenandoah, which, by the late 19th century, had become celebrated as part of the Lost Cause narrative embraced by Confederate veterans. Grimball presented at least one speech about his service on the noted cruiser. After his death in 1922 at age 82, however, his service was placed in a larger perspective that took into account his time at Fort Moultrie and the Star of the West encounter. “Without a doubt this constitutes the longest service of any man on either the Union side or the Confederate side of the long struggle and makes a unique distinction,” declared The State newspaper in Columbia.

Perhaps the finest tribute to his memory came from a writer, who added a personal touch. “Those who knew Mr. John Grimball in his later years will remember him with warm affection for many reasons, and, perhaps chief among these, for the youthfulness of his spirit. He was one of those men who seemed destined never to grow old. Years came upon him, but, until his last illness descended, his heart remained young.”

Ronald S. Coddington is editor and publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.