By Elena Colón-Marrero

State identification cards did not exist in 19th-century America. As a consequence, proving a person’s identity could require creativity and innovation.

Two court-martial cases that arose at the end of the Civil War—one in Albany, N.Y., and the other in Springfield, Ill.—reveal how some litigants relied on more than the spoken word to determine identity. The cases of Simon Burke and William Gemmill, both tried in September 1865, used photographs as a key method to identify suspected deserters.

On June 22, 1865, Simon Burke of the 134th New York Infantry was arrested at Albany for desertion—the second time he was accused of this crime. The military believed that Burke had deserted his regiment in 1864, and enlisted in New Hampshire as a substitute under the alias John Brown. The judge advocate had only one witness, John F. Chute, who was unable to provide solid testimony regarding Burke’s identity. The prosecution’s only hope to prove that Burke and Brown were the same man thus rested in a muster roll and two photographs, both of which the judge advocate entered into the official record of the court.

The muster roll described John Brown as a 28-year-old Canadian, 5 feet 10 inches, with gray eyes, brown hair and sandy complexion, who had enlisted as a substitute for William H. Messer of New Hampshire. To prove that this man was actually Simon Burke, the prosecution requested a photograph of Brown from Maj. J.W. Caldwell, the commanding officer at the General Rendezvous at Concord, N.H. Caldwell replied that there were six men named John Brown under his command. “We have pictures of all of the above named men,” he wrote. “If you could forward a picture of the deserter in question, we could the more easily identify him.”

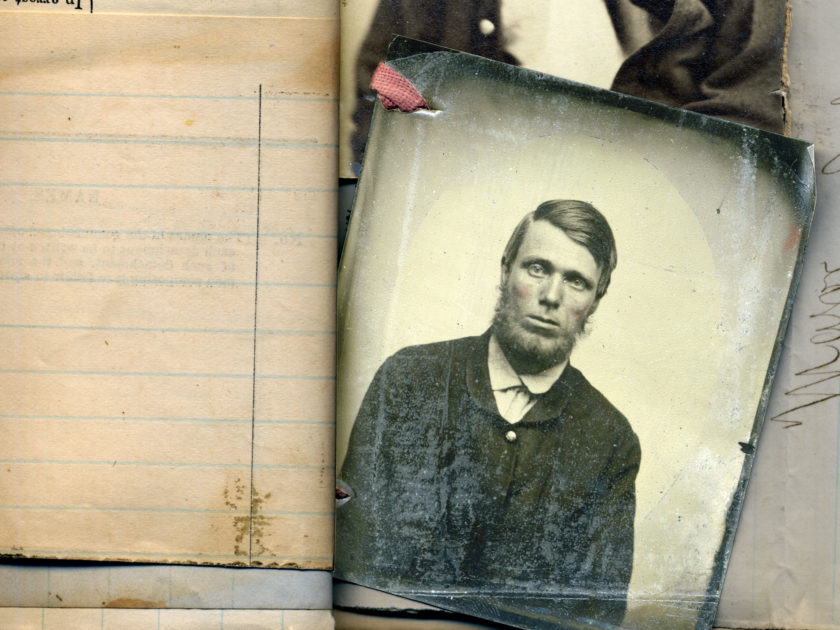

The prosecution complied with the request and received a tintype of a John Brown in return. The tintype (misidentified as an ambrotype in the court record) showed the substitute, John Brown, dressed in a Union sack coat. In court, the judge advocate submitted this photograph along with a photograph of Simon Burke, which had been taken around the time of his arrest.

William G. Weed, Burke’s lawyer, objected to the use of the photograph. “The picture or photograph offered in evidence proves nothing,” he argued. “There is no evidence that it is the picture or likeness of the John Brown enlisted as stated in the descriptive list, and no evidence how, when or where it was obtained or procured.” The court agreed, acquitting Burke and ordering his release on October 15, 1865.

William Gemmill of Illinois was not as fortunate. Gemmill (sometimes spelled Gemmell) was drafted into the Union army on Oct. 22, 1864. But there was a problem. The enrollment officer misspelled his name as “Gamble” during the enrollment process prior to conscription. As a consequence, Gemmill disregarded the draft notice he received, since there was no “William Gamble” residing in his home. His failure to report for duty or procure a substitute led to his arrest in May 1865.

The prosecution called upon several witnesses to verify Gemmill’s identity, including the enrollment officer and the family friend who had served Gemmill his draft papers. In his defense, Gemmill provided a carte de visite from the album of his brother-in-law, Samuel Dehaven, to show that he was William Gemmill and not William Gamble. Nevertheless, the court found Gemmill guilty of desertion on Oct. 27, 1865. But because of the long period he had already spent in prison, his release was ordered, upon the payment of a $100 fine.

These cases likely represent some of the earliest instances where photographs were used in American military courts.

These two cases foreshadowed the wide use of photographs in the future to determine identity in judicial proceedings. Prior to the Civil War, photographs for identification were rarely used in courtrooms. In the late 1850s, a few lawyers employed pictures to show landscapes in land disputes, or to compare multiple copies of items or documents to determine which were authentic and which were fraudulent. But no attorneys had yet realized the potential of photographs to identify people in court.

The court-martial cases of Simon Burke and William Gemmill likely represent some of the earliest instances where photographs were used in American military courts; they may also be the earliest examples of photographs that were utilized to identify litigants. According to legal scholar Jennifer L. Mnookin, “By the 1870s, photographs were frequently used in criminal cases to prove identity, either of the victim or of the defendant.”

The prosecution in Burke’s case and in the defense of Gemmill’s foresaw the potential in photographs to prove guilt or innocence.

Sources: Court-Martial Case Files MM-2875 and MM-3005, General Court-Martial Case Files, Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Jennifer L. Mnookin, “The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy,” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 10 (Winter 1998): 1-74.

Elena Colón-Marrero is a graduate of Christopher Newport University where she studied History and Spanish. She has interned at The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, The Mariners’ Museum Library, and the Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center. She currently is studying at the University of Michigan’s School of Information specializing in Archives and Records Management and Preservation of Information.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.