An estimated 155,000 Virginia men served in the Confederate army, a remarkable 89 percent of eligible volunteers. Here are some of their portraits and personal narratives.

Teenaged Trooper

According to his military service record, William Henry Magann was 18 years old when he enlisted in The Campbell County Rangers in May 1861. In fact, he was only 15. The eldest of three boys born to a Bedford, Va., overseer and his wife, he and his comrades became Company I of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. They participated in numerous engagements, including the largest cavalry battle of the war at Brandy Station, Va. At Appomattox, most troopers in the regiment eluded capture and avoided surrender by cutting their way through federal lines. Magann likely numbered among those who escaped, and he did not sign the oath of allegiance to the U.S. government until late May 1865.

A veteran at age 19, Magann became a tanner, married in 1875 and started a family that grew to include three boys. His second son was named Robert Lee Magann.

Around the turn of the century, Magann and his wife, Eliza, moved to Plant City, Fla. Magann died there in 1913 at age 67.

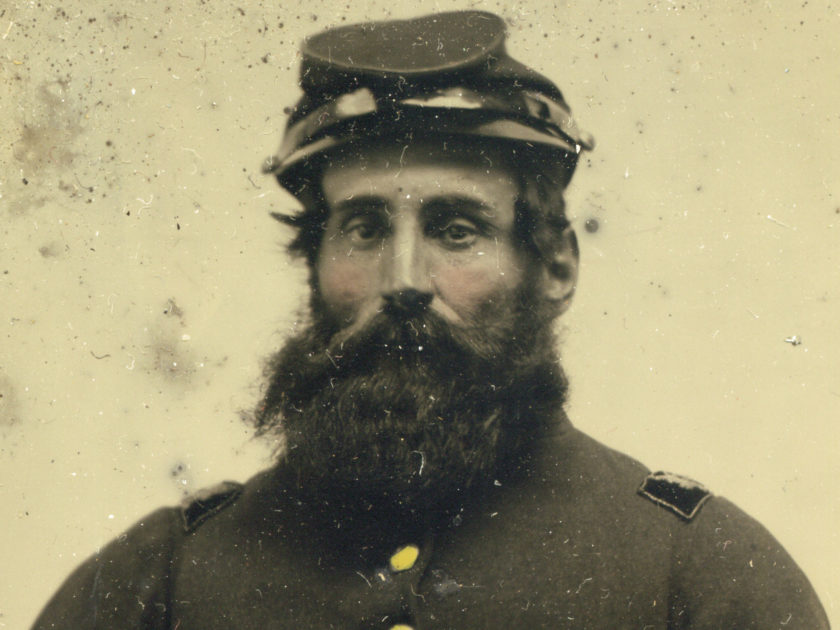

Wednesday, March 9, 1863

On this date, William Russell Orr sat for his portrait, and noted the fact in pencil on the inside of the case. He holds a U.S. Model 1832 foot artillery sword. Though he did not record the location, it was likely near Abingdon, Va., where his regiment, the 64th Virginia Mounted Infantry, camped. A private in Company G, Orr had enlisted the previous summer, leaving behind his wife, Rebecca, and six children. They remained at home in Lee County, located not far from Abingdon in the state’s southwestern corner.

The regiment preferred to remain stationed in its home counties, and the men actively resisted transfer. They were eventually ordered into neighboring Tennessee.

The relocation proved disastrous. Orr and his comrades became part of a 2,300-man garrison at Cumberland Gap—directly in the path of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Union army. On Sept. 9, 1863, exactly six months after Orr had his photo made, the garrison surrendered to Burnside, paving the way for a federal advance on Knoxville.

Orr and about two-thirds of the 64th became prisoners of war. Transported to Camp Douglas on the outskirts of Chicago, Orr would never leave, dying of smallpox a few days before Christmas 1864. His remains were buried in a mass grave.

Service Interrupted

After the Confederate government discovered that Pvt. George Schleicher was a woodworker and machinist, his days in the army came to a swift close. A native of Darmstadt in the German state of Hesse, he immigrated to the U.S. about 1848, when he was 19 years old. He made Richmond his home, married and started a family.

In April 1861, he traded his tools for a musket when he joined Company G of the 1st Virginia Infantry. He posed for this portrait soon after his enlistment. Within a few months, the government detached him on special duties—likely factory work that took advantage of his skills as a machinist. Evidence suggests he served in this capacity until the Confederate government evacuated the capital.

Schleicher flourished as a woodworker in post-war Richmond. Later in life, mental health issues consumed him. His family feared for his safety, and hid his pistol. But he found it on July 4, 1894. A few days later he knelt as if in prayer, pressed the muzzle to his head and pulled the trigger. He was 65.

A Scotch-Irish Boy at Catlett’s Station

As bolts of lightning slashed across the Virginia sky on the evening of Aug. 22, 1862, trooper Samuel Holmes Kerr splashed through mud and muck in a violent rainstorm. He and his comrades in the 1st Virginia Cavalry were hell-bent on a daring mission to disrupt federal supply lines to Union forces in occupied Northern Virginia.

The commander of the Southerners, Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, was the original colonel of the 1st. On this stormy night, Stuart led his men to victory—and avenged federal cavalry who had captured his cape and trademark plumed hat a few days earlier.

Kerr emerged unharmed from the action, though his horse was shot and killed. He represented the grit and determination that characterized the soldiers in the ranks. “He served during the whole war and was one of those brave Scotch-Irish boys who made the war last four years,” observed a comrade. A Shenandoah Valley native born in Augusta County, Kerr joined the Valley Rangers in April 1861. It later became Company E of the 1st. One of the stalwarts of the Army of Northern Virginia, the regiment participated in more than 200 engagements. Kerr survived it all. He evaded capture at Appomattox, and signed the oath of allegiance to the federal government on May 24, 1865.

His post-war life was as action-packed as his war service. He married three times and fathered eight children who lived to maturity. Upon his death in 1917, Kerr was dressed in his Confederate uniform, placed in a casket draped with the Stars and Bars, and buried in a Presbyterian Church cemetery in his home county.

Flags for a Lady Friend

Samuel Gordon Knox presented this artwork depicting the first and third Confederate national flags to a friend, Miss Georgia Lewis. Knox, a private in Company B of the 30th Virginia Infantry, may have been courting Lewis, or the two may simply have enjoyed a platonic friendship. Whatever their bond, it did not end in marriage. In 1875, Knox married Malvina Crutchfield Young in Fredericksburg, Va., and began a family that included three sons and a daughter.

Knox died in 1909. Details about Georgia Lewis are unknown.

Commander of Forces at John Brown’s Hanging

One visitor to Charles Town, Va., commented on the large military presence to maintain order in the days leading up to the execution of John Brown. “The noise and confusion, the hustle and bustle consequent upon the collection of so large a body of troops in a country village continue unabated.”

The writer also recognized the commander, Maj. Gen. William Booth Taliaferro. “I learn that he is a very accomplished officer, and with great affability united the qualities of a strict and stern disciplinarian.”

Taliaferro, 38, sat for this portrait that, according to tradition, was made on Dec. 2, 1859, the day Brown hanged after his conviction of charges of treason, murder and fomenting a slave insurrection at Harpers Ferry. The man standing to Taliaferro’s left is believed Col. David Addison Weisiger. The identity of the other man is not known at this time.

Educated at Harvard and William and Mary, Taliaferro had a long military history with experience in the Mexican War and the Virginia state militia. He also served in the Virginia House of Delegates. In late November 1859, Virginia Gov. Henry A. Wise brought in Taliaferro to take charge of the military situation at Charles Town. In addition to his regular duties, he also escorted Brown’s wife, Mary, to a final meeting with her condemned husband, and to arrange for the return of the body to her for burial.

Taliaferro accomplished all his assignments. When war divided the country less than two years later, he served as colonel of the 23rd Virginia Infantry, and went on to command on the brigade and division levels as a brigadier general. He fought at the Battles of Second Manassas and Fredericksburg in Virginia, Fort Wagner in South Carolina and Olustee in Florida.

After the war, he returned to his home in Gloucester County and served as a state legislator and judge. He died in 1898 and age 75. His wife, Sally, and seven children survived him.

John Brown’s Final Moments

Parke Poindexter, a member of the 1st Regiment Virginia Volunteers, witnessed the hanging of John Brown on Dec. 2, 1859. He described the event to his sister, Mary, in a letter written a week after the execution.

“I saw old Brown and other prisoners several times. There was nothing particularly striking in the appearance of old Brown. He was a man sixty-odd years of age, naturally thin, and considerably shrunken by confinement and his wounds, with a long face, an equal mixture of gray and sandy hair, and long beard. My company, F, was stationed very near the gallows upon the day of Brown’s execution, and I witnessed the whole proceeding. Brown mounted the scaffold as calmly and quietly as if he had been going to his dinner: he did not exhibit the slightest nervous excitement or fear; not a muscle moved, nor was there the slightest nervous excitement; he stood erect and calm as if he were upon post. He struggled very little after the trap fell from under him. He hung upon the gallows thirty-seven minutes. There were upon the field of execution about two thousand troops, and the military display was the most beautiful I ever saw.”

Poindexter would see much more of military life after the war began. In May 1861, he left his job as an attorney and became captain and commander of Company I of the 14th Virginia Infantry. He suffered a serious wound when shrapnel struck him in the pelvis during the Battle of Suffolk, Va., on April 24, 1863. He succumbed to his injuries six months later in Richmond. Poindexter was 37 years old.

Gallego’s Treasurer

When the 16th Virginia Infantry formed in the summer of 1861, its volunteers included Albemarle County native George Annesley Barksdale. The 26-year-old was appointed to be regimental quartermaster, a natural fit considering his professional experience. In recent years, he worked as treasurer of Richmond’s Gallego Flour Mills. His father was a partner in the prosperous company, and its brick warehouses were part of the city skyline.

Barksdale remained with the 16th for only a few months. In September 1861, he joined the Pay Bureau of the Quartermaster Department as a captain, a position that better suited his talents and could be of greater benefit to the Confederate army. He served throughout the war, and appeared on the list of officers and men paroled at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. By this time, the Gallego Flour Mills had been destroyed by the conflagration that engulfed the business district in the wake of the evacuation of the capital by soldiers and government workers.

The loss of Gallego seems not to have affected his personal wealth. Active in business and a life member of the Virginia Historical Society, he died after suffering a massive stroke in 1910. His wife, Edmonia, and a daughter survived him.

Encounter After Appomattox

After the surrender at Appomattox, Surg. William Hoskins bid farewell to his comrades in the 59th Virginia Infantry and set off on horseback for home. A cousin joined him for the 125-mile ride to King and Queen County on the opposite side of the state.

According to a story passed down through the family, “They rode through the smoke and rubble of Richmond into the countryside beyond. In passing a house hidden in trees behind a hedge they heard women screaming followed by raucous laughter.” Hoskins and his cousin spurred their horses and jumped the hedge. Inside the house, they discovered three Union stragglers abusing the women. Hoskins opened fire with his .44 caliber Starr revolver, which he kept as part of the surrender terms. He killed two of the stragglers, while his cousin killed the third man.

Hoskins was accustomed to saving soldiers, not killing them. Back in 1861, he served briefly as a cavalry lieutenant before he joined the state’s 26th Infantry as assistant surgeon. In 1863, he advanced to full surgeon and a new assignment with the 59th Virginia Infantry. He served in the defenses of Petersburg during the months before the surrender at Appomattox.

Hoskins made it safely home after the encounter with the Union stragglers, and resumed his career as a physician. He also served in the Virginia legislature. He died in 1895. His wife, Janette, and five children survived him.

One of Lee’s Couriers

General Robert E. Lee placed a high value on reliable intelligence. “Information should be obtained by our own scouts—men accustomed to see things as they are and not liable to excitement or exaggeration,” he wrote in early 1863. One of those men, Pvt. John Thomas Willingham, appears here with a Confederate-made Kenansville saber. The image bears the date, in period ink, March 27, 1863. A farmer from Clark County, Va., Willingham served in Company A of the 39th Battalion Cavalry, which was assigned to Lee’s headquarters as scouts, guides and couriers.

One historian noted, “Genl. Lee took great pride in mingling with several of the companies, and always looked after their comfort. Indeed, the ‘Scouts, Guides and Couriers’ were a favored lot, as other soldiers would frequently say; but on the battle fields as they were seen speeding with orders to corps commanders through shot and shell, many would ask, how can those fellows escape?”

Willingham left the battalion in October 1863. He went on to serve in the 6th Virginia Cavalry and the 43rd Battalion Cavalry, better known as Mosby’s Rangers. He was paroled in late April 1865 and returned to Clark County. His wife, Amanda, and two daughters survived him upon his death in 1880.

Saved by the Bible

George Marion Koiner had his baptism under fire in the Shenandoah Valley on May 8, 1862. A corporal in the 52nd Virginia Infantry, Koiner was part of the force that defended against Union attacks along Sitlington’s Hill. After a severe fight, the enemy retreated to nearby McDowell, for which the battle is named. The action was one of the Confederate successes in Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s celebrated Valley Campaign.

Koiner, a farmer who had enlisted in the Waynesboro Guard the previous summer, suffered a minor wound in the right arm. He came close to instant death, however, when a bullet struck him full force in the torso. The ball tore through a coat pocket and diary, before coming to rest in the middle of a Bible behind the journal.

One month later at the Battle of Port Republic, Koiner was wounded again, this time by a gunshot in the left hand. The injury crippled him and led to his discharge in January 1863.

Koiner rejoined the army in 1864 as a private in the 39th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry. Its four companies served as Gen. Robert E. Lee’s personal guard. Koiner is not listed on the rolls of soldiers surrendered at Appomattox, though he was paroled the following month in Staunton, a short distance from his home in Waynesboro.

Koiner lived until 1912. His wife, Julia, and eight children survived him. He was remembered as a man with “a good mind, clever attainments, broad common sense, with good judgment.”

Jackson’s Provost, Lee’s Aide

Behind the scenes of the Battle of Fredericksburg, Maj. David Benjamin Bridgford, seated right, occupied a unique position. As Chief Provost Marshal to Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, it fell to Bridgford to police stragglers in the 2nd Corps.

Bridgford was well suited to staff work. The son of a British army officer, he was born in Canada and raised in Richmond. In peacetime, he was a successful businessman with interests in steamboat companies. He also served as captain and commissary in the 1st Regiment Virginia Volunteers.

When the war began, Bridgford assumed command of a company of the 1st Battalion Virginia Infantry, popularly known as the Irish Battalion. He joined Jackson’s staff in late 1862. A few months later, in January 1863, Bridgford filed his Fredericksburg after-action report. In it, he stated Jackson’s order to “shoot all stragglers who refused to go forward, or if caught a second time, upon the evidence of two witnesses to shoot them.” Bridgford noted, “I am most happy to state I had no occasion to carry into effect the order. … Had I occasion to carry it into effect, it certainly should have been executed to the very letter.”

On May 10, 1863, Jackson succumbed to complications from a wound received at Chancellorsville. Bridgford accompanied the general’s remains to Richmond, where they lay in state prior to burial in Lexington, Va. Bridgford then joined the staff of Gen. Robert E. Lee, and sat for this portrait alongside Brig. Gen. James Dearing, probably in the spring of 1864.

One year later, Dearing was dead after suffering a mortal wound at the Battle of High Bridge, during the waning days of the Appomattox Campaign. Meanwhile, Bridgford was surrendered and paroled with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865. A few weeks later he arrived in New York City, where he prospered as a merchant until his death in 1888. His wife, Georgette, whom he had married in 1861, and two children, a boy and a girl, carried on his name. His son, born in 1866, was named Jackson Lee Bridgford, in honor of the two generals his father had served with distinction.

A Rockbridge Dragoon at Tom’s Brook

A running series of cavalry clashes in the Shenandoah Valley during the summer and autumn of 1864 took a heavy toll on Confederates. Under near-constant attack by Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s forces, the ranks of Southern troopers were depleted and replacements not forthcoming.

On Oct. 9, 1864, the weakened Confederates were routed at the Battle of Tom’s Brook. Among the wounded was David Dice of the 14th Virginia Cavalry. Described as a “gallant soldier,” he suffered an injury at some point during the fight. A 23-year-old farmhand from Rockbridge County, Dice was one of four brothers to serve in the Second Rockbridge Dragoons, which became Company H. The other brothers, George, John and William, came through the war unscathed.

Though the nature of Dice’s wound was not reported, it kept him out of action for almost three months. By this time, the war was drawing to its conclusion.

After the end of hostilities, Dice returned to the life of a farmer in the Rockbridge County community of Raphine, about 20 miles south of the battlefield where he was wounded. He died in 1900 at age 62. Though he outlived his only son, his wife, Emma, survived him.

A Native Baltimorean and “One of Virginia’s Noblest”

On March 12, 1863, George Franklin Masson inscribed this portrait to his mother with a patriotic sentiment: “He is one of Virginia’s noblest defenders long may he live to enjoy the Liberty for which he is now fighting and for which so many of her bravest sons have been made to bite the dust, crushed by an insolent foe.”

Born in Baltimore, he was an adopted son of Virginia. Masson moved from Maryland to Gloucester County, Va., about 1851 when he was 9 years old. When the war erupted, he left his job in the lumber business and enlisted as a private in the Gloucester Light Dragoons, which became Company A of the 5th Virginia Cavalry.

Masson had advanced to corporal when he posed for this portrait. Five days after he inscribed it, he suffered a wound in the inconclusive Battle of Kelly’s Ford, part of cavalry operations along the Rappahannock River in Virginia. The exact nature of his wound was never reported. He survived his injury, returned to the regiment, and finished the war as a sergeant.

In 1865, he returned to Baltimore and started a transfer and express business. He died in 1916 at age 75. His wife, Susan, and two sons who worked in the family business survived him.

“I hear the Booming of Artillery, and Must Prepare to Move”

Near Goose Creek in Northern Virginia, Gen. J.E.B. Stuart determined to rest his weary forces on the Sabbath day of June 21, 1863. The federals had other plans. Heavy attacks pushed Stuart back. He made a stand at the village of Rector’s Crossroads, while his artillery hurriedly limbered up and fled oncoming infantry.

As Stuart’s 2nd Horse Artillery left its position, an artillery shell struck with deadly force. The blast tore one man to pieces before striking Pvt. Charles D. Saunders in the leg above the knee.

Saunders was carried to the rear in care of a reverend. A servant named John, who attended to Saunders, also came along. The enemy overran town, leaving a dying Saunders and John to the fate of the enemy. The federals told John that he could leave. But he refused, and remained with Saunders, who bled to death before a surgeon could perform an amputation. He was 19.

Saunders’ body was placed in a casket, and sent home to Lynchburg for burial in the family plot at a local cemetery. An epitaph on his stone obelisk offers a moving tribute to a sacrificed soldier. It includes a quote from “An Elegy on the Death of John Keats” by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

“But I hear the booming of artillery, and must prepare to move. ‘Trust in god’ and ere the day closed, our brave, our beloved had ‘outsoared the shadow of our night’ in the dew of his youth, in the springtime purity of a heart, whose every pulsation was for love, faith, and duty. His soul passed away through fiery portals to join in the harmonies of the skies.”

Wounded by a Recipient of the Medal of Honor

On a crisp autumn day in 1864, Pvt. Hugh Hamilton and his comrades in the 4th Virginia Cavalry, known as the Black Horse Cavalry, attacked Union troops at Waynesboro, Va.

A squadron of federals from the 3rd New Jersey Cavalry, led by Capt. George N. Bliss of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, rode out to check the advance. During the approach, Bliss pulled up at a low barricade and observed the Virginians, arranged in columns of four, had turned back. Here, Bliss sensed an opportunity to strike a blow and ordered a charge. He jumped his horse over the barricade and made a beeline for the Virginians, unaware that his men had not followed him. “I had ridden past a dozen of the enemy before I discovered my desperate situation,” Bliss recalled. “Fifty men behind me were shouting, “Kill that damned Yankee!”

Bliss wounded four Virginians before he was captured, and after a bullet staggered his horse. Hamilton numbered among the casualties. The exact nature of his injury went unreported. He made a full recovery. At some point he posed for this portrait wearing a pleated battle shirt, possibly the only known photograph of a Black Horseman so attired.

Hamilton returned to his home in Fauquier County after the war, and went on to serve as county treasurer. He died on March 28, 1928. Capt. Bliss, who had received the Medal of Honor for his lone charge, died four months later.

Pharmacist and Artillerist

On May 7, 1861, one of the earliest exchanges of hostile fire since Fort Sumter occurred at Gloucester Point opposite Yorktown, Va. On that day, the Union steam tug Yankee and a shore battery manned by a detachment from the Richmond Howitzers traded shots. One of the gunners present was Pvt. Thomas Roberts Baker, a Richmond native and Howitzers member. A prominent pharmacist, his name had been bandied about in the press as a delegate to the recent Virginia Secession Convention.

Baker’s tenure in the Howitzers was short-lived as the Confederate army needed medical men. In July 1861, he was detached as a druggist in the general hospital at Bigler’s Mill, located near Williamsburg. He served here and elsewhere with the medical department for the remainder of the war.

After the end of hostilities, Baker became a partner in one of the biggest drug firms in the country and served as president of the American Pharmaceutical Association. Though an introvert who preferred evenings at home with family, he was active in veteran’s groups. Baker lived until 1906, dying after a long period of declining health. His wife, Maria, and son, Henry, were at his bedside.

Educator, Soldier

Benjamin James Hawthorne reenacted a charge across an open field at Gettysburg on a summer’s day in 1913. The old soldier and the aged veterans with him were full of fight and pride, even though their youth had faded, like the war, into the distant past.

Exactly 50 summers earlier, then Capt. Hawthorne marched across the same field into the bloody inferno that was Pickett’s Charge. Two weeks prior, he had been detached from his regiment, the 38th Virginia Infantry, for temporary duty on the staff of Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead. They marched in the second line of battle. Armistead would not come back. He suffered a mortal wound as he held his sword aloft with his hat perched on the tip of the blade. Hawthorne received a gunshot wound in the left arm before he reached the stone wall, from behind which the enemy poured sheets of flame from musket and field cannon. Somehow, he managed to make his way back across the field littered with dead and dying men.

Hawthorne recovered from his injury, returned to command his company in the 38th, and surrendered at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.

A gifted student before the war who had graduated valedictorian of the Randolph-Macon Class of 1861, Hawthorne went on to a 40-year career as a college professor. He spent much of his tenure in Oregon at Corvallis College until 1884, and the University of Oregon thereafter. An energetic and innovative educator, he established a formal curriculum of psychology at the University of Oregon.

According to one observer, he was a popular, though eccentric, professor. “Hawthorne was a tall man whose style of beard seemed to elongate him even more; he apparently had little expression in his eyes—sort of dreamy, and they would not seem to focus on anything…but they made a definite impression on his students.”

Hawthorne was also remembered for his appearances at the annual Grand Army of the Republic parades. “He showed up in full Confederate dress and hollered rebel yells at the marching Union veterans,” noted one writer.

After his retirement in 1910, he earned a law degree and became an attorney. The G.A.R. was one of his clients.Hawthorne died in 1928 at age 90. He outlived his wife, Emma, and four of his five children. His surviving daughter, Pearl, identified Hawthorne at the blue and gray reunion at Gettysburg in 1913.

Wounded in the Fighting at Chancellor House

Chin whiskers cannot hide scarring on the neck of John Thomas Hull, the result of a wound he received during the Battle of Chancellorsville. A second lieutenant in the 2nd Virginia Infantry, Hull commanded Company E of his regiment, and participated in the successful breakthrough of Union lines near the Chancellor House. At some point during the action, a minié bullet pierced his neck and partially paralyzed his right arm and hand.

The injury deprived the 2nd and the rest of the Stonewall Brigade of a promising officer, who had worked his way up the ranks. Back in April 1861, 22-year-old Hull left his employment as a carpenter and enlisted as a sergeant in his hometown “Hedgesville Blues,” which became Company E of the 2nd. He survived the Peninsula and Valley Campaigns, though he was wounded in the latter at the Battle of Port Republic. He also emerged unscathed from Antietam.

The wound he received eight months later at Chancellorsville ended his combat career. He spent much of the rest of the war in hospital camps in Richmond, and received a discharge in January 1865. He later returned to Hedgesville, which by this time had become part of the new state of West Virginia. He remained there the rest of his days, apart from a brief stint in Missouri, where he worked as a prison guard. Hull died in 1925 at age 86. He outlived his wife, Mary Ann, whom he had wed in 1881.

Shot During a Dismounted Cavalry Fight

In the wake of the 1864 Overland Campaign, as Yankee invaders moved against Richmond, sharp clashes occurred with increasing frequency around the Confederate capital. One engagement occurred on June 1 in Ashland, a scant 15 miles due north of the city. By all accounts, the fierce fight by dismounted cavalry ended in a drawn, inflicting approximately 180 combined casualties. Among the wounded Southerners included Capt. Irwin Cross Wills of the 13th Virginia Cavalry, who suffered a gunshot in the chest.

Wills had started his military service in May 1861 as a third lieutenant in the 5th Virginia Cavalry, and left the regiment after his one-year term of enlistment had expired. Soon after, he joined the 13th and saw plenty of action, including the 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, during which his horse was shot and killed, and numerous other actions along the Petersburg and Richmond fronts. His wound at Ashland kept him away from the 13th for most of the remainder of the war. He surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Wills returned to his home in Southampton County and became a civil engineer. He died in 1912 at age 71. His wife, Margaret, whom he had married during the war, and at least two children, survived him.

“He Turned the Tide of Battle”

In the supreme moment of crisis for Southern arms at the First Battle of Manassas, Arthur Campbell Cummings emerged as a central figure. An 1844 graduate of the Virginia Military Institute with a stellar record in the Mexican War, he had organized the 33rd Virginia Infantry in June 1861.

Weeks later at Manassas, the regiment occupied the extreme left of Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s brigade. According to Sgt. Maj. Randolph Barton of the 33rd, Cummings and his lieutenant colonel reconnoitered the ground about 100 yards ahead, peered over the crest of a hill and discovered the enemy in force. Both commanders walked quickly back to their line. Cummings stated, “Boys, they are coming, now wait until they get close before you fire.”

Meanwhile, routed South Carolina troops streamed through Jackson’s rock-solid lines and prompted the comment that gave Jackson his nom de guerre. “Stonewall” ordered his men not to fire until the federals had advanced to within 30 paces.

Back in the 33rd, Cummings and his boys saw a color bearer appear on the crest, followed by the blue battle line. Several Virginians raised their muskets and fired. Then, Barton recalled, “The shrill cry of Colonel Cummings was heard, ‘Charge!’ And away the regiment went, firing as they ran, into the ranks of the enemy.”

The rest of Jackson’s Brigade soon followed, and before long the enemy took to full retreat. Barton credited Cummings. “He turned the tide of battle at First Manassas,” and added, “I should think to Colonel Cummings the circumstance would be of extraordinary interest, and that he would time and again reflect how little he thought, when he braced himself to give the order to his regiment, that he was making a long page in history.”

Cummings left the army in 1862, returned to his family in Washington County, Va., and became as a captain in the Abingdon Home Guards. After the war, he served a stint in the Virginia legislature. Cummings died in 1905. His wife, Elizabeth, and a son predeceased him.

“My Horse Was Killed Under Me”

A number of former students and alumnae from Randolph-Macon College in southwest Virginia joined the army in the wake of war. They included Benjamin Haden Anthony of Campbell County, who had spent a year on campus in 1854-1855. He enlisted as a private in Company I of the commonwealth’s 2nd Cavalry in the spring of 1862. Though his stay in the regiment was only six months, it was eventful. Anthony was present for duty for Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign, and fought in the major Confederate victory at the First Battle of Winchester on May 25, 1862.

In a letter written the next day to his mother, he noted, “My horse was killed under me and I was truly thankful that I was saved.” He added, “I hope this unholy war will soon be closed and then we can come home once more if I am spared.”

A few months later, Anthony hired a substitute to fill his place. The practice was as controversial in the South as it was the North. According to a wartime report, as many as 50,000 to 150,000 men may have served as substitutes—some paid as much as $3,000 and more to enlist. It is not known how much Anthony paid his substitute, but evidence suggests he could afford it. He owned 12 slaves in 1860. The Anthony family in Campbell County owned a total of 123 slaves.

The man Anthony hired, N. Roberts, disappeared from the muster rolls in December 1862.

Anthony’s motivations for leaving the army have been lost to time. One possible explanation was his family: He had a wife and two young children at home. His exact whereabouts for the rest of the war remain unclear, though he may have possibly returned to the army as a private in the 11th Virginia Infantry. Anthony received a parole in his home county in May 1865 and lived until 1910.

Impromptu Color Bearer

During the thick of the cavalry fight at Kelly’s Ford, a shot felled the horse upon which rode the color bearer of the 5th Virginia. Another trooper seized the flag and carried it through the rest of the fight. The courageous soldier was Harry Wooding, a clerk from Danville, Va., who, at 19, had become a battle-hardened veteran.

Two years earlier, then 17-year-old Wooding enlisted after he watched a drum and fife corps march through Danville. He joined the 18th Virginia Infantry as a private in Company B. A few months later, he suffered a shoulder wound at the Battle of First Manassas. The injury proved slight, and he soon found himself back among his comrades, who elected him company sergeant.

Wooding transferred to the 5th in time to participate in the encounter at Kelly’s Ford on March 17, 1863. The battle was the result of a Union plan to destroy Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry brigade, which included the 5th and three other Virginia regiments. The Union troopers failed to accomplish their goal, though they fought well. In his after-action report, Lee stated, “My whole command acted nobly; sabers were frequently crossed and fences charged up to, the leading men dismounting and pulling them down, under a heavy fire of canister, grape, and carbine balls.” Lee praised several men, including Wooding, whom he “especially commended.”

Wooding went on to fight at Gettysburg and other major actions. He eventually returned to Danville and became its mayor, a post he held for 46 years. He died at age 94 in 1938, having outlived his wife, Ella, and a son.

Southern Guardsmen of Campbell County

Four members of the Southern Guards of Campbell County, which became Company B of the 11th Virginia Infantry, posed in the shape of a V. Though it is not known if this formation was intentional, the identity of the volunteer who stands on the right is clear. John W. Anthony, a 19-year-old farmer who enlisted in April 1861, fought four years with the 11th and later the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. He suffered three wounds during his service, including an injury to his wrist after being struck by a spent bullet or shell at the Battle of Seven Pines in 1862, and a gunshot to the right thigh on April 1, 1865, during the chaotic final days of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Anthony survived his wounds and lived until age 78. He died in 1920 at home in Campbell County.

The Wisdom of a Private in the Ranks

Senior military leaders and politicians hotly debated the question of whether Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army should invade the North in 1863. Their views are well known. Less so are the opinions of the men in the ranks. One perspective, by Pvt. Benjamin Washington Jones of the Surry Light Artillery, appeared in a letter to his wife from Camp Letcher, Va., on June 15, 1863.

Referring to Lee, Jones observed, “Whether he will go beyond the Potomac again this summer, as he did last, has not yet reached the ear of the private in these parts. I hope, however, there will be no further movement that would have the appearance of an invasion of Northern soil. Southern soldiers are fighting for this very thing, more than anything else, namely, to resist invasion, invasion of their native land and soil, and if our own army should turn about and become the invader of the North, I believe it would tend to unite that people more firmly and lead them to fight us harder than ever. This is a private’s view of the matter, and it may be all wrong, But I, for one, would prefer to fight at home. I think I could strike harder here.”

After the loss at Gettysburg a few weeks later, Jones, who did not participate, might have rightly pointed to his earlier statements on the invasion. He didn’t. Rather, he focused on the surrender of Vicksburg, not the defeat at Gettysburg, as the more serious blow against Confederate arms.

Jones remained with the Surry Light Artillery until April 8, 1865, when he escaped and avoided surrender the next day at Appomattox. Unrepentant to the end of his life, he went to his grave in 1918 without formally surrendering to the federal government.

Petersburg City Guardsmen

Petersburg ranked as the nation’s 50th largest city on the eve of the Civil War. The bustling town was well represented by militia companies, including the Petersburg City Guard. Its membership, including this trio, was well uniformed, including the battle shirt, frock and shell jacket seen here. The array of dress styles underscores the wealth of its members. The company was also well-drilled—it inspired at least one piece of music, the City Guard Quick Step.

After the war came, the Guard became Company A of the 12th Virginia Infantry. It included the man on the left, Pvt. John William E. Young. The Petersburg native and son of a tobacco inspector is the only identified soldier in this group. Young served in the regiment through the Peninsula, Maryland and Fredericksburg Campaigns.

In March 1863, he was discharged after he paid a substitute to take his place in the ranks. That man, Joseph F. Williams, proved an able soldier as evidenced by his battle record—he suffered a wound at Spotsylvania in May 1864 and was captured at the Battle of Burgess Mill, also known as Boydton Plank Road, five months later.

Meanwhile, Young rejoined the army as a private in the Petersburg Horse Light Artillery. He survived the war and ranked as corporal at the time of his surrender and parole in April 1865. He died in 1893. His wife, Mary, and three children survived him.

Gun Maker, Richmond Defender

The ill-fated raid on Richmond by Union Col. Ulric Dahlgren and his command prompted forces across the capital into action. One company of local defense troops, the Armory Battalion, took up a position east of the city. These men were led by Capt. Henry Fitzgerald Jr., a native of Glasgow, Scotland. His day job was supervising stock makers at the Richmond Armory carbine factory.

On March 1, 1864, Dahlgren’s cavalry overran Fitzgerald’s command at Green’s Farm. Fitzgerald was captured during the action and paroled. The raid came to an end the next day after Dahlgren was killed. Papers found on his body purportedly detailing plans to assassinate Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet stirred controversy on both sides of the divided country.

Fitzgerald’s brief time in uniform was his second of the war. In 1861, he had joined the 6th Virginia Infantry as a first lieutenant. About this time, he posed for this portrait, with his wife, Catherine, and their first child, Alexander. But when authorities in Richmond discovered that he was a pattern maker for the Danville Railroad prior to his enlistment, he was detached from duty to work in the Ordnance Bureau. He served in this capacity in Richmond for the rest of the war, aside from the Dahlgren Raid and a stint to set up a carbine factory in Tallassee, Ala., in late 1864.

After the war, Fitzgerald returned to his hometown of Manchester, Va., and went on to serve as City Sergeant, an administrative position. Catherine died tragically in 1868 after the birth of their fourth child, a daughter, who did not survive. He soon remarried and started a new family that grew to include three children. He died in 1900 at age 66.

Twice Wounded, Twice Captured

The exact spot where John David Tanner fell during Pickett’s Charge was not recorded. But his wounds left an indelible record. A corporal in the Bedford Grays, which became Company F of the 28th Virginia Infantry, he suffered a gunshot in the upper left arm and injuries to both legs. Unable to retreat or escape, he fell into federal hands, and was transported that same day to a Union field hospital for treatment.

This was the second time the 21-year-old Bedford County native landed on the casualty list. A year earlier during the Peninsula Campaign, he suffered an undisclosed wound at Gaines’ Mill. He spent six months in the hospital before he returned to the 28th.

His hospital stay after Gettysburg did not last as long. Three months later, he became a prisoner of war. Tanner was paroled and exchanged. He returned to the regiment before the end of 1863. He would join the casualty list once more. On April 5, 1865, during the last days of the Army of Northern Virginia, Tanner was captured and confined at Point Lookout, Md. He eventually signed the oath of allegiance to the federal government.

Tanner went on to become a city councilman in Lynchburg, Va. He married in 1868, and started a family that included two boys who lived to maturity. He lived until 1924, and was survived by his wife and a son.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.