By Ronald S. Coddington

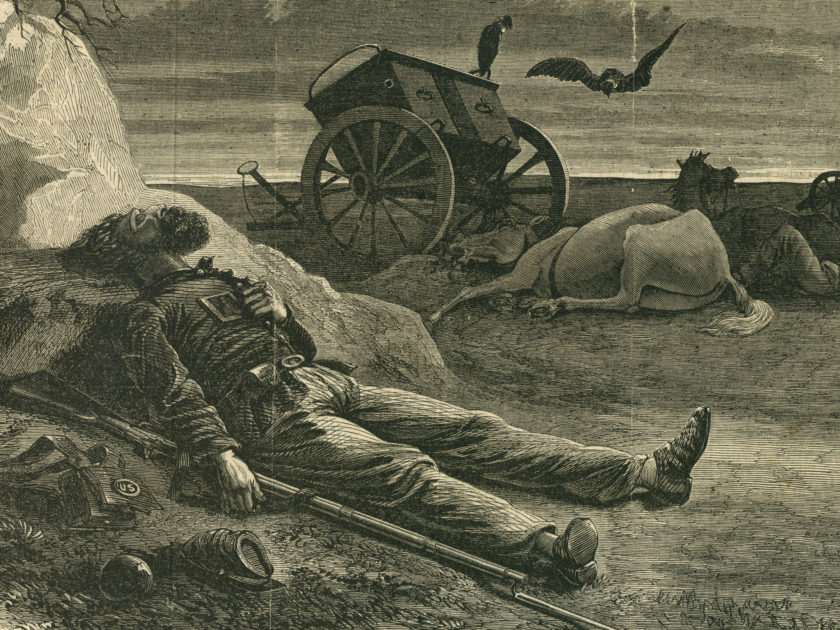

One of the most poignant personal stories of the Battle of Gettysburg is the death of Union Sgt. Amos Humiston.

Killed during the first day of fighting on July 1, 1863, his identity was lost in the chaos of battle. He died clutching an ambrotype of his three young children. A description of the photograph, which became known as the “Children of the Battlefield,” was circulated across the North in an effort to discover the identity of the deceased soldier. Finally, Humiston’s wife, Philinda, responded to the query and received a carte de visite copy, which she confirmed as a portrait of her two sons and daughter.

Though fallen soldiers were found with photos on other battlefields, the Humiston story survives as the best-known account of military death and photography. The other accounts have been lost with the passing of time.

Also forgotten was a unique poem, “The Carte de Visite.” In patriotic and romantic verse, an anonymous poet tells the story of a handsome soldier boy struck down in the thick of battle. Upon the body of the fallen warrior lies his portrait photograph.

The poem appeared in two local newspapers, Connecticut’s Hartford Evening Press and the Daily Illinois State Journal, on the same day, Aug. 29, 1862— about a year before Humiston met his fate at Gettysburg. Two national publications, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, printed it soon afterwards. The publication of the poem in such a diverse group of periodicals suggests that it was mass mailed to editors across the North in hopes of attracting attention.

If true, the strategy worked. By 1864, perhaps fueled by the real-life Humiston story, the popularity of the poem soared. That same year it was featured in two books of collected war poetry, Pen-Pictures of the War and Lyrics of Loyalty. In the latter, editor and New York City journalist Frank Moore noted, “The purpose of this collection is to preserve some of the best specimens of the Lyrical Writings which the present Rebellion has called forth.” As a result, “The Carte de Visite” appears alongside works by literary giants Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

The success of the poem can be attributed to current events as much as any artistic merit. The carte de visite photograph, a recent French import, was all the rage in America, as grieving families struggled to come to terms with growing lists of war casualties. Its publication on the eve of the Second Battle of Bull Run, and soon before the bloodbaths at Antietam and Fredericksburg, underscored its timeliness.

The poem was not without its critics. In January 1864, a correspondent for the Springfield Daily Republican in Massachusetts observed, “There has been a poem floating about generally, with the title, ‘The Carte de Visite,’ which has a pleasant jingle and a patriotic sound, and is woven out of the war staple, which unhappily is cheaper than cotton or it could not be so much used. The thing is anonymous, or one might write to the author, and now it has found a permanent place in a collection of poems.”

The writer also needled the anonymous author for romanticizing the war. “A wayworn soldier stops at a gate and tells the story of a fight to a mother and daughter, and how a young man was killed; of course ‘his hair clustered in curls round his noble brow.’ It is dangerous for such men to go into battle, for they are always the victims. … But then the old soldier goes on to say that he did not know the youth’s name, but he took this picture from his breast, ‘it is as like him as like can be,’ and when they saw it the young girl fainted and the mother ‘bent low.’ Now did the youth carry his own picture? and what for? And is it a romantic and touching thing for a youth to carry his own picture close to his breast? On your honor as an editor, dissolve me of this doubt.”

Although the correspondent raised reasonable questions about the plausibility of the plot, readers seemed not to care. It was not the critic’s voice that drove the poem into oblivion, however, but the end of hostilities in 1865 that marked the beginning of a decline in public interest of all war poems.

“The Carte de Visite” slowly faded into obscurity, though it reappeared again as late as 1922 in a collection of Decoration Day, or Memorial Day, poetry. By this time the carte de visite had also disappeared, and the title of the poem had been changed to “The Picture.”

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

The Carte de Visite.

“‘Twas a terrible fight,” the soldier said;“Our Colonel was one of the first to fall,Shot dead on the field by a rifle ball-A braver heart than his never bled.

A group for the painter’s art were they;The soldier with scarred and sunburnt face;A fair-haired girl, full of youth and grace;And her aged mother wrinkled and gray.

These three in a porch, where the sunlight cameThrough the tangled leaves of the jessamine vine,Spilling itself like golden wine,And flecking the doorway with rings of flame,

The soldier had stopped to rest by the way,For the air was sultry with summer heat;The road was like ashes under the feet,And a weary distance before him lay.

“Yes, a terrible fight—our ensign was shotAs the order to charge was given the menWhen one from the ranks seized our colors, and thenHe, too, fell dead on the self same spot.

“A handsome boy was this last. His hairClustered in curls round his noble brow,I can almost fancy I see him now,With the scarlet strain on his face so fair.”

“What was his name? have you never heard?Where was he from, this youth who fell?And your regiment, stranger, which was it, tell?”“Our regiment! It was the Twenty-third.”

The color fled from the young girl’s cheek,Leaving it as white as the face of the dead.The mother lifted her eyes, and said:“Pity my daughter—in mercy speak!”

“I never knew aught of this gallant youth,”The soldier answered; “not even his name,Or from what part of our State he came,As God is above, I speak the truth!

But when we buried our dead that nightI took from his breast this picture—see!”“It is as like him as like can be;Hold it this way, toward the light.”

One glance, and a look, half sad, half wild,Passed over her face, which grew more pale,Then a passionate, hopeless, heart-broken wail,And the mother bent low o’er the prostrate child.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.