During the first months of the Civil War, the Union urgently needed heroes.

Fortunately for the patriotic Northern press, it did not have to look too far to find them.

In April 1861, Maj. Robert Anderson’s name splashed across front pages as rebel artillery decided the fate of his beleaguered garrison holed up in Fort Sumter.

The martyrdom of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth dominated newsprint in May. The flamboyant Zouave drillmaster-turned infantry colonel had just hauled down a Confederate flag from the roof of a hotel in Alexandria, Va., when a pro-secession proprietor gunned him down.

In June, an officer garnered headlines and electrified the nation after his wildly aggressive charge in Northern Virginia at the little remembered Battle of Fairfax Court House.

Charles Henry Tompkins, a Virginian who remained loyal to the Union, emerged as an unexpected hero. He had dropped out of West Point in 1849, probably much to the chagrin of his father, Col. Daniel D. Tompkins, a distinguished Academy graduate.

Young Tompkins did not stay away from the military for long. In the mid-1850s, he joined the cavalry as a private and received his military education on active duty on the western frontier.

By the start of the war, he had returned East and ranked as a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. On the evening of May 31, 1861, Tompkins set out with about 75 troopers to scout enemy positions and strength in the Fairfax Court House area. During the wee hours of June 1, he and his men encountered a small guard of Confederate pickets. Various versions of what happened next were reported, including a June 4 New York Herald report filed by a special messenger who claimed to have interviewed Tompkins. The reporter described Tompkins as a modest young man of medium height and build with an intelligent face, and added a personal observation: “He is just the man for a dashing enterprise gallantly executed.”

The interview generally followed the accepted narrative. According to the messenger, “The picket guard consisted of three men. One was taken prisoner, and Lieutenant Tompkins said he would hang him if he did not tell correctly the number of soldiers.” The picket estimated a maximum of 150, when, in fact, the number was closer to half that many.

Undeterred, Tompkins and his cavalrymen rode into town. He reportedly told the Herald, “The Court-House street turns at right-angles to the road. As our men rode round the corner a squadron of cavalry was soon drawn up in line across the street. A charge was sounded, and the line was broken, our men sweeping on. A company of infantry next appeared, drawn up on a cross street. They charged and broke them.” A third charge also succeeded before the rebels rallied and drove them off.

“During the whole time of their presence, there was constant firing from windows and doors. Doors would open time enough for the discharge of a musket and then close,” the Herald messenger stated. “Two horses were shot under Lieutenant Tompkins. A third, his own, was shot in the neck, and fell upon him, bruising him slightly.” Other reports indicate he injured his foot.

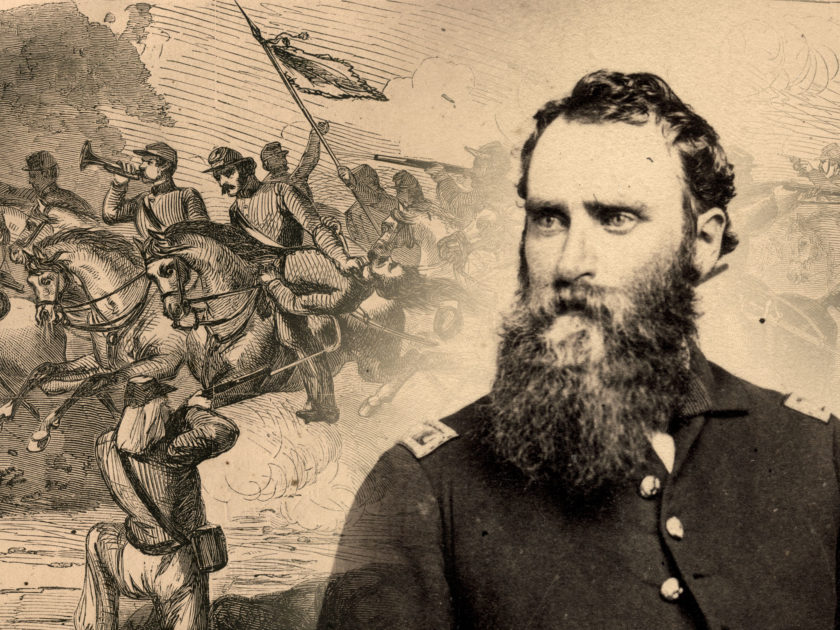

The Herald described one scene that inspired a Harper’s Weekly engraving in its June 14, 1861 issue. “One dragoon was shot by the side of the Lieutenant, but there was no opportunity to get him off. ‘But,’ said Tompkins, ‘I think even they will give him a Christian burial.’”

The battle was also memorable for other reasons. Casualties on the Confederate side included the first field-grade officer to suffer a wound in hostility—Lt. Col. Richard S. Ewell. The first Confederate combat death also occurred here when Capt. John Q. Marr of the Virginia militia was shot and killed. At least one source claimed that Tompkins shot Marr with a borrowed carbine, a story since largely discredited.

One of the buildings from which the Confederates fired, the Union Hotel, was formerly managed by James Jackson, the innkeeper who had killed Col. Ellsworth on May 24, 1861. Sgt. Francis E. Brownell, in turn, killed Jackson.

Brownell’s deed became the first wartime action recognized by a Medal of Honor. Tompkins’ was the second act recognized, though he did not receive his Medal until 1893. A year after he received the decoration, Tompkins retired as a colonel after a long military career. He lived until 1915.