The sight of a man missing an arm or leg rarely occurred before the Civil War, observed a newspaper editorial in the Confederate capital during the waning days of the conflict. Such individuals were assumed to be victims of a railroad accident or other calamity.

When war came, and soldiers disabled by battle wounds appeared on Richmond’s streets, they received much attention. As the conflict dragged on, veterans with visible scars of battle became common. “No man need feel at all singular, or have any sensitiveness about attracting attention, by being without an arm of leg,” stated the essayist in the March 29, 1865, issue of the Richmond Dispatch, adding, “The gentleman with legs and arms are now becoming oddities, and sometimes suspicious characters.”

The editorial continued, “Whenever the people meet a Confederate soldier without an arm of leg, they know the missing limb of that man is buried where he would have freely given his life, ‘on the field of honor’; and he looks more of a man, more grand, symmetrical, than many men with legs; and everyone feels a sincere reverence and love for him.”

A similar transformation unfolded in the United States. In his 1862 poem, “The Empty Sleeve,” David Barker (1816-1874) of Maine wrote, “What a tell-tale thing is an empty sleeve—What a weird, queer thing is an empty sleeve.” Much as his counterpart in Richmond, Barker connected the soldier to the epic struggle engulfing the nation: “To the top of the skies let us all then heave one proud huzza for the empty sleeve.”

Another example is a poem penned in 1864 by William E.H. Comfort (1844-1888) of the 35th New Jersey Infantry during his imprisonment at Andersonville: “The scars upon our bodies from musket balls and shell, The missing limb, the shattered arm, a truer tale will tell. We have tried to do our duty, in sight of God on high.”

Wartime writings like these recognized paid tribute to these survivors. Such public expressions in the form of poems, editorials, songs and stories helped the citizens of two countries come to terms with what they saw on their own streets with increasing frequency—friends and neighbors bearing the visible reminders of war’s terrible toll.

The impact of these public writings on the men who carried these honorable scars is hard to calculate. How much did they ease the transition of survivors into society? Did the thoughtful words of inspired writers comfort their psyche?

In an era where mental health was subordinated to and often expressed in terms of physical attributes, and the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder lay a century in the future, documenting the psychological impact of combat is more anecdotal than quantitative.

It is easy to imagine that such writings helped to normalize wounded warriors as they adjusted to life in peacetime.

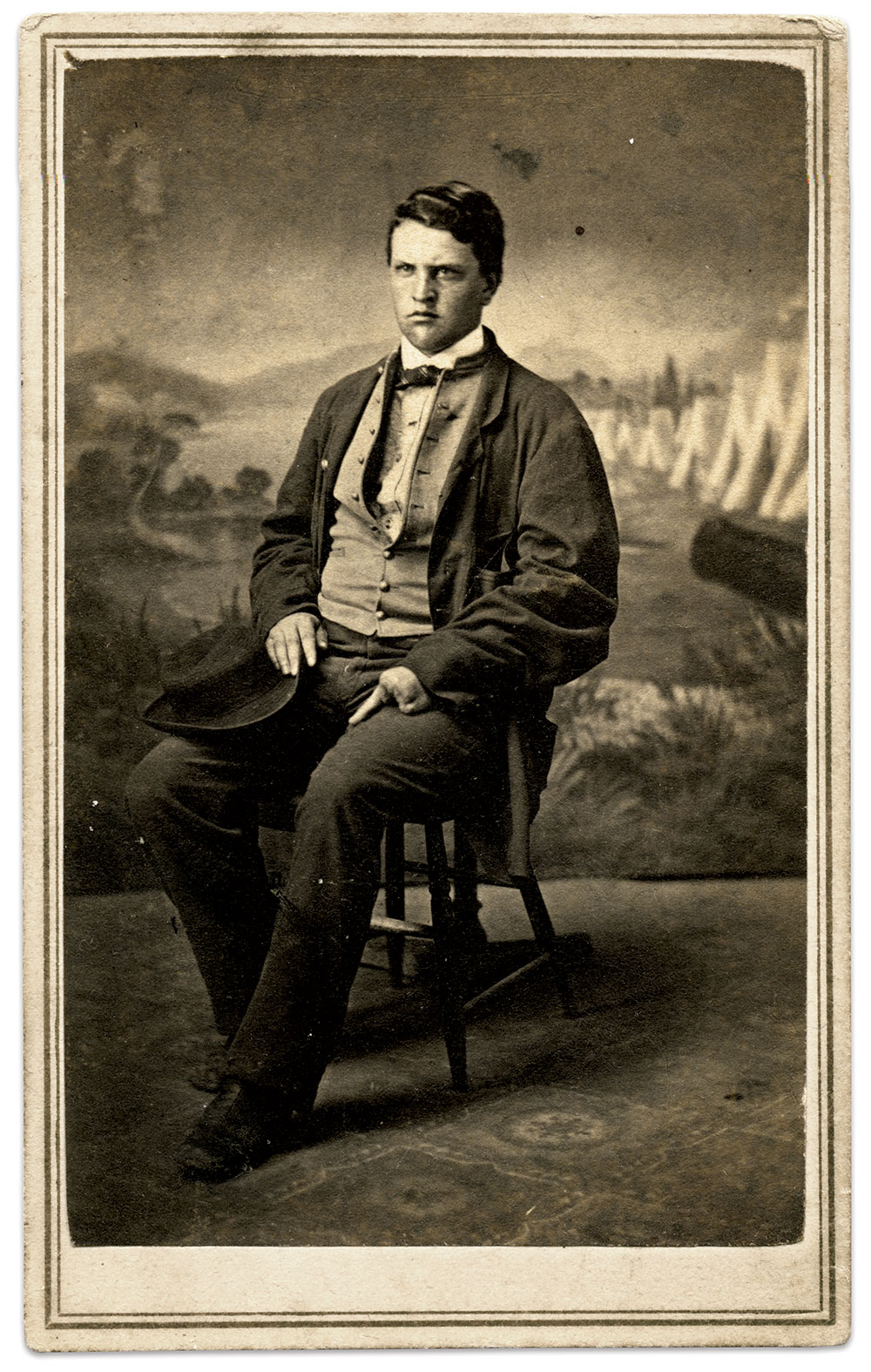

We also have a visual record in the form of the photographic portraits featured here. These images picture veterans during or soon after their recuperation, dressed in uniforms with empty sleeves, shattered arms supported by slings, and crutches or wheelchairs to substitute for a missing leg or legs. These veterans posed with purpose: They wanted comrades, family, and friends to see them as survivors in process of overcoming their disabilities and transitioning into society as useful citizens despite physical limitations. And so we see them today, frozen in time, at seminal moments in their lives. Some of these portraits, in the carte de visite format, may have been sold by the soldiers and sailors to provide extra income to supplement military pensions.

The portraits pictured in this gallery are not to be confused with graphic medical case study photographs of soldiers in various stages of undress exposing stumps, scars, and other effects of surgical procedures.

These portraits are not to be confused with the graphic medical photographs of soldiers in various stages of undress exposing stumps, scars, and other effects of the surgeon’s scalpel. These photographs were made at the request of the medical establishment to document noteworthy cases for purposes of study and evaluation by army physicians, surgeons, and other researchers. They originate with the U.S. Medical Department in Washington, D.C. Surgeon General William A. Hammond issued a circular in May 1862 that called on doctors to gather specimens of “morbid anatomy” for the new Army Medical Museum, established to improve soldier care. They sent in shattered bones and other examples. On New Years Day 1863, the museum’s catalog was printed. It contained the first reference to the submission of photographs of specimens. In June 1864, another circular specifically requested medical officers to submit photographs of unusual cases.

The post-war chapters of the stories of the men pictured here vary. The fates of some, their names currently lost in time, are unknown. Others went on to productive, prosperous lives. They blended into society and gained recognition for their civic leadership and business acumen. Those who suffered hardship as a result of their disabilities were defined by their war wounds and singled out by faith-based groups, secular charities, veterans’s organizations, the government—and the media.

In the former Confederate States, an 1866 editorial in The Weekly Telegraph of Macon Ga., revealed, “There are many brave and noble sons of the South, who battled manfully for the Southern cause, but are not dead, who stand in need of monuments of affection and gratitude from those for whom they suffered all but death. There are many empty sleeves to meet our gaze, and many missing limbs to be replaced. There are hundreds who, by the misfortunes of war, have been rendered totally unable to labor for their daily bread.—These are the “Heroic Living,”—dead, however, to prosperity and worldly ease.”

The Northern states faced a similar situation. An 1870 editorial in the Public Weekly Opinion of Chambersburg, Pa., called for the funding of home to care for disabled soldiers. The writer noted, “We daily see these men, (and who does not blush to see them?) To whom we owe the preservation of our government, the homes we enjoy, and almost everything we possess, hobbling about our streets upon crutches, with missing limbs, and otherwise so enfeebled as to be entirely unfitted for any remunerative employment, begging their bread from door to door, or sitting upon the corners of the streets turning an organ for a few pennies the charitable passer-by may feel disposed to bestow.”

Whatever fate had in store for these survivors, they carried battle scars forever. The often quoted Union veteran Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911) recognized the enduring psychological impact of a disabling wounds in his poem, “The Monk of La Trappe.” Set in medieval Europe and touching on themes of sacrifice, isolation and inner conflict, he likely drew upon his wartime observations and interactions in writing the the final stanzas:

Perhaps some dream, as sinks yon evening sun,

Leads back the dramas of his stormy prime, —

Beauty embraced, foes quelled, ambitions won,

A tangled web of courage and of crime.

Those years, long wholly vanished, throb for him

Like pangs which haunt the amputated limb.

Missing legs

Surrounded by the Stars and Stripes, Empire State colors, muskets, wreaths, and flowers, Lt. Col. Robert Avery of the 102nd New York Infantry poses with his corps badge and without the right leg amputated after he suffered a combat-ending wound in November 1863 at Lookout Mountain, Tenn.—the Battle Above the Clouds. His gallantry earned him a brigadier general’s commission. Months earlier at Chancellorsville, he suffered gunshots in the neck and chest, and had only just returned to the 102nd when enemy lead shattered his leg. Avery lived until age 73, dying in 1912.

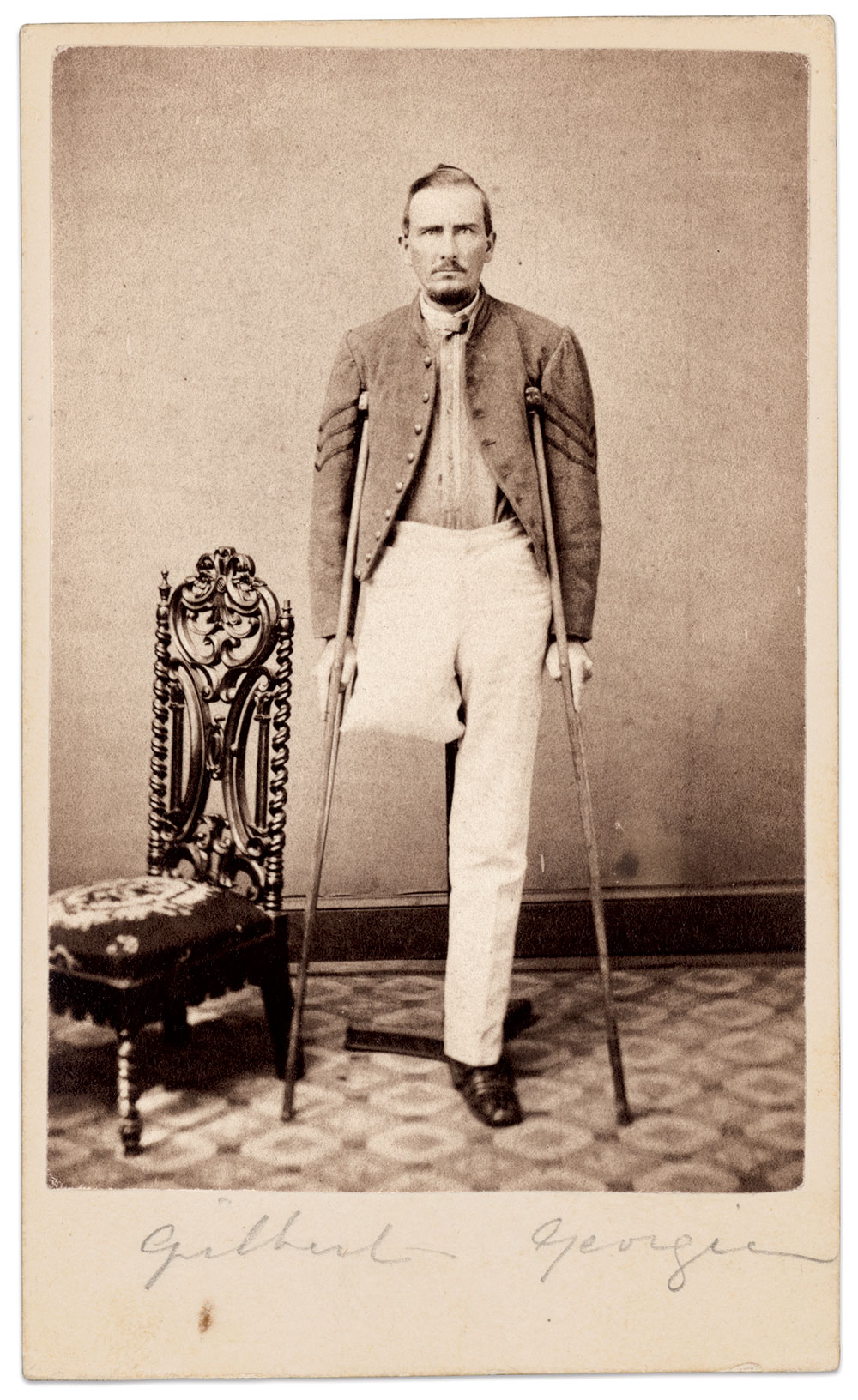

During the fighting on July 2, 1863, in the Wheatfield at Gettysburg, Sgt. Richard Thomas Gilbert (1831-1910) of the 18th Georgia Infantry suffered a gunshot fracture to his right thigh. Left behind when the Confederates retreated, the 31-year-old Georgia native fell into enemy hands. Union surgeons amputated the limb. He recuperated at Camp Letterman in Gettysburg and the U.S.A. General Hospital in Baltimore before being paroled in late 1863. Gilbert returned home to his wife, Julia, and two children. The couple added seven more kids to their family.

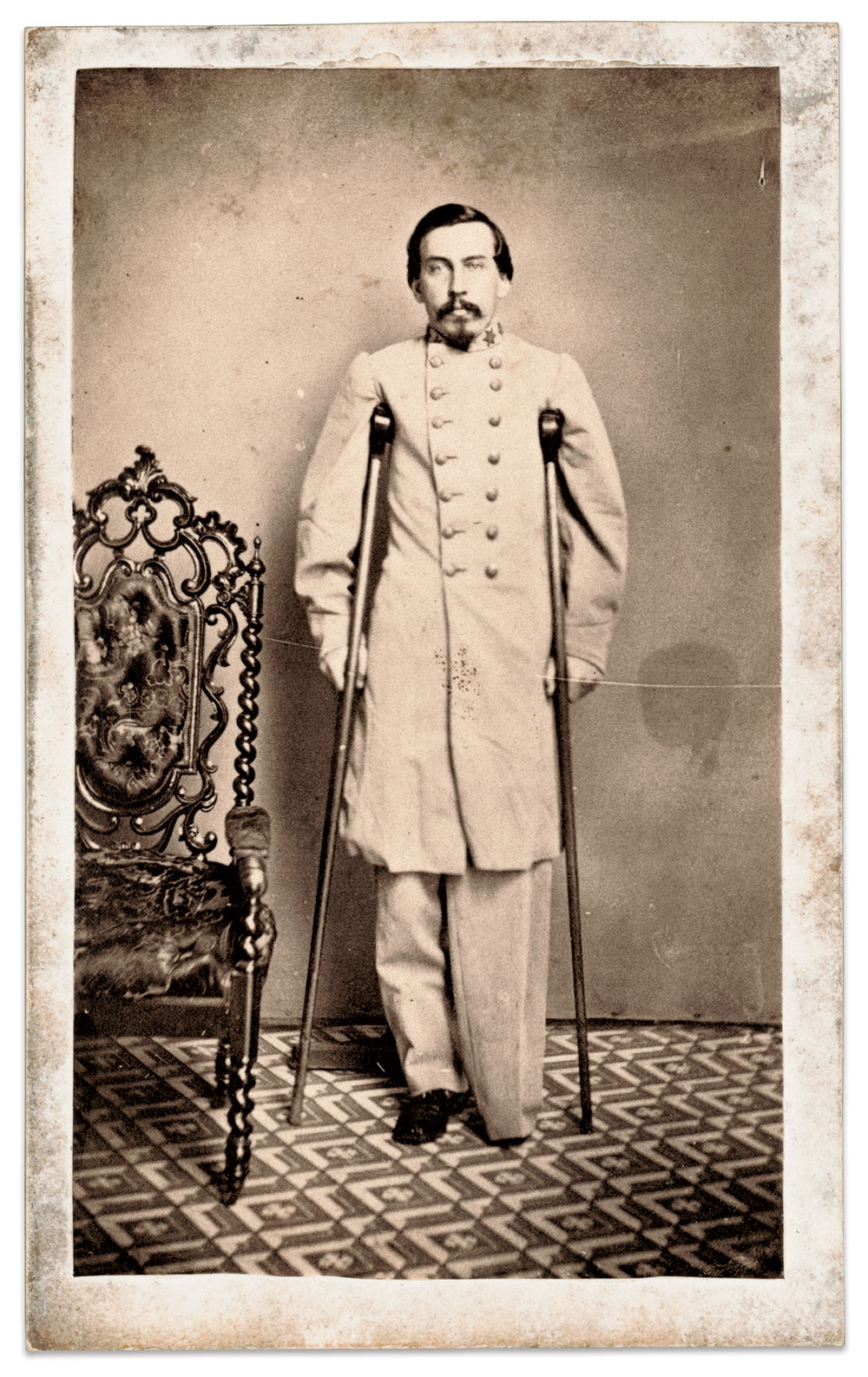

A skirmish in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley on October 8, 1864, left 1st Lt. and Adjutant Legh Wilber Reid (1833-1908) of the 25th Virginia Cavalry desperately wounded in his left thigh. Surgeons amputated the next day. An 1858 Virginia Military Institute graduate, Reid started the war as with the 36th Virginia Infantry and received a wound at Fort Donelson in 1862. After losing his position in a reorganization, he declined a commission in the 17th Virginia Cavalry and recruited a battalion that joined the 25th. Reid hoped to return to the army after losing his leg, but the war ended before he could act. He went on to a career in the railroads, and as Assistant Registrar of the U.S. Treasury Department during President Grover Cleveland’s first administration.

The neatly folded trouser leg and crutches hide the missing limb of this Union soldier seated beside a comrade. The cannon ball between them may be no more than a photographer’s prop, or perhaps part of the story as to how the soldier lost his leg. Roughly four in ten lower body amputations involved the leg, according to the U.S. Medical Corps.

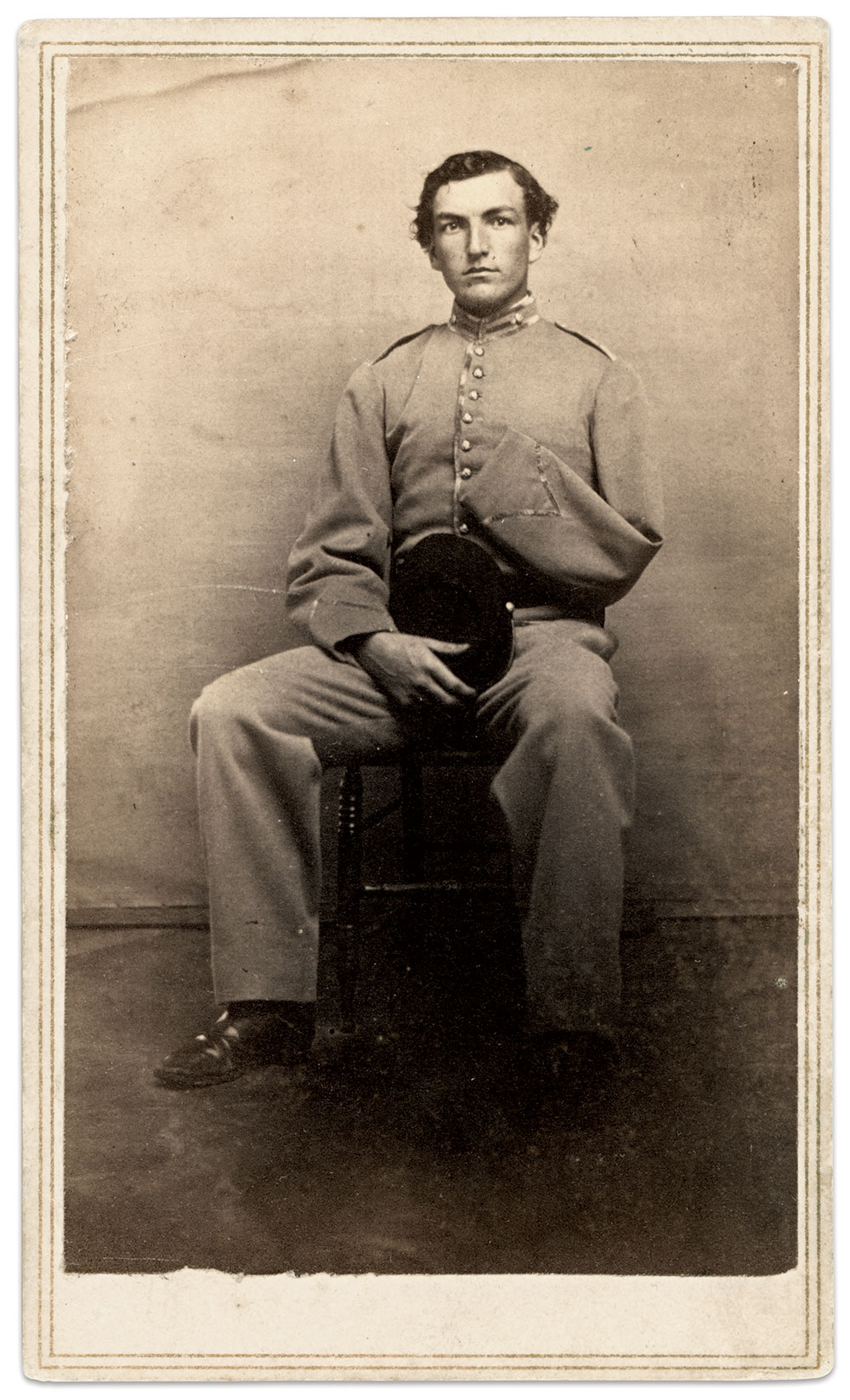

On March 15, 1865, in Forsyth County, N.C., five men—two Confederate army deserters, two citizens with Union sympathies, and one Black person—were shot and killed in broad daylight, their bodies left on a roadside. The executions, committed without a trial, were ordered by Capt. Reuben Everett Wilson (1842-1907), commanding Company A of the 1st North Carolina Sharpshooters Battalion. Wilson, a native of the county, made his way from the scene to the front lines in Virginia where, at Petersburg on April 2, a shell struck his left leg. Hospitalized the same day, surgeons amputated the mangled limb. He is pictured here in his uniform jacket with a patch hiding his collar insignia, and buttons that appear non-military, or military buttons concealed by paint or thin cloth. These alterations suggest he posed after the issuance of orders discouraging the wearing of Confederate insignia in late 1865. Wilson started his war service as a second lieutenant in the 21st North Carolina Infantry and joined the Sharpshooters after the expiration of his one-year enlistment. He suffered wounds in two engagements in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862. Charged with murder in May 1865 for the Forsyth County executions, the court released him from custody in December because of failing health. Amnesty laws passed by the state the following year cleared him of all charges and any wrongdoing.

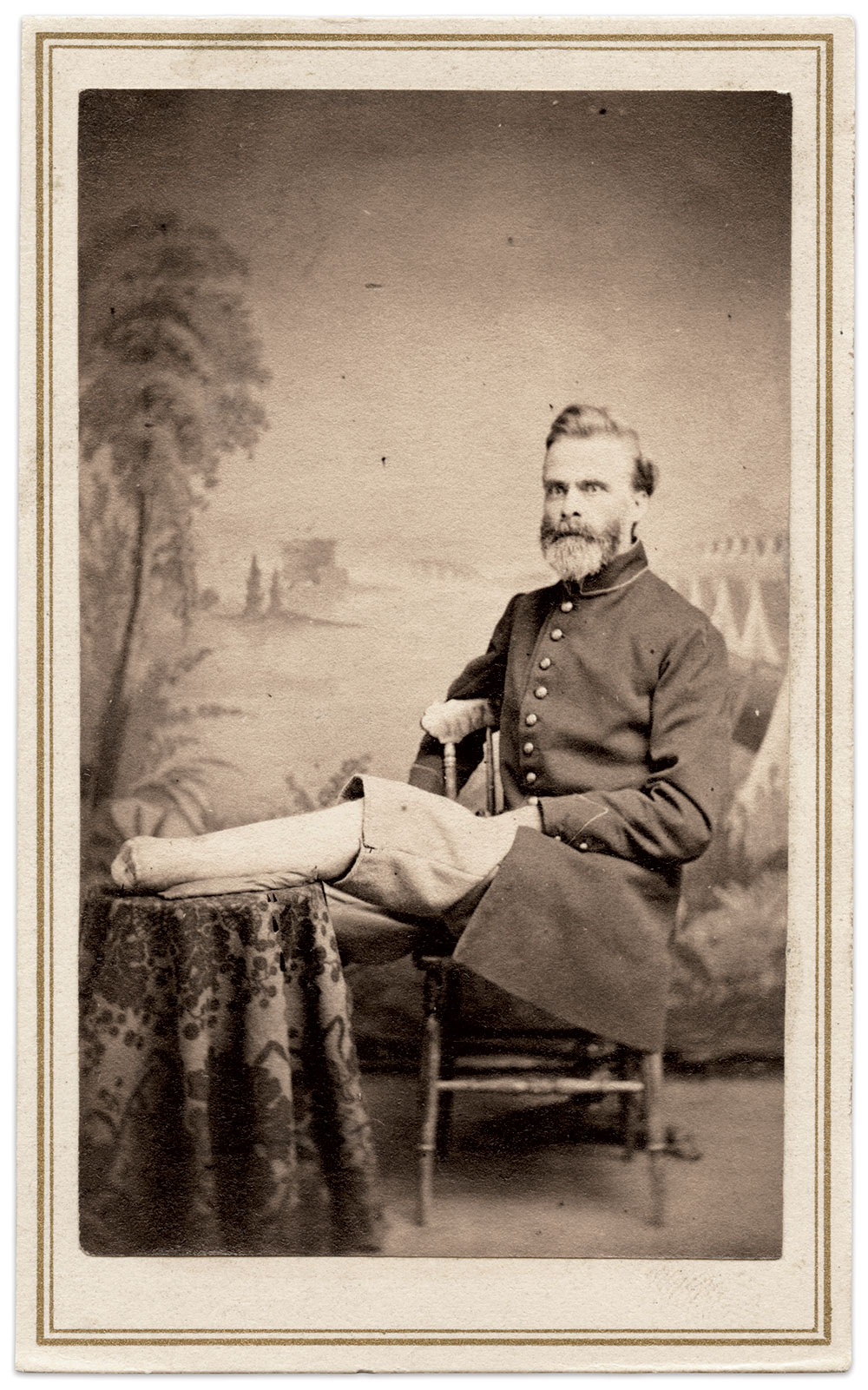

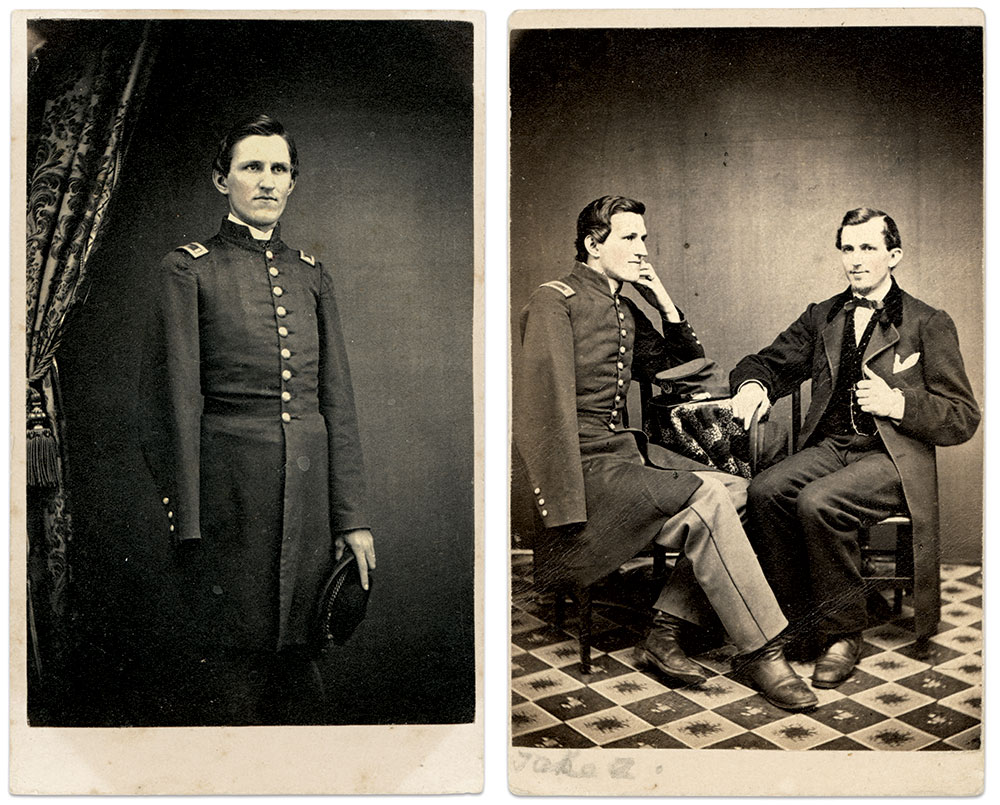

Two Union lieutenants and native Pennsylvanians posed for this portrait in Philadelphia, likely during their recuperation at the city’s U.S.A. General Hospital. The gray bearded man is 1st Lt. John C. Nelson (1821-1904) of Company K, 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, born in Spring Hill, about 80 miles east of Pittsburgh. He suffered gunshots in the shoulder and right leg near Chantilly, Va., in February 1863, during an attack by troopers in Col. John Singleton Mosby’s Rangers. He left the army in May 1864. Despite recurring pain from his amputation, Nelson lived a useful life as a farmer, miller, judge, and a member of the Grand Army of the Republic. The officer next to him is 2nd Lt. Thomas M. Nugent (1842-1899), born in Philadelphia and raised from boyhood in Loogootee, Ind. A member of Company D of the 27th Indiana Infantry, he suffered bullet wounds in both thighs and left knee during the defense of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. Surgeons amputated his left leg. Following his hospitalization at Camp Letterman and Philadelphia he completed his recuperation in Covington, Ky., and Camp Chase, Ohio, where he resigned in May 1864. He settled in Bedford, Ind., and raised a family until typhoid ended his life at age 57.

Missing arms

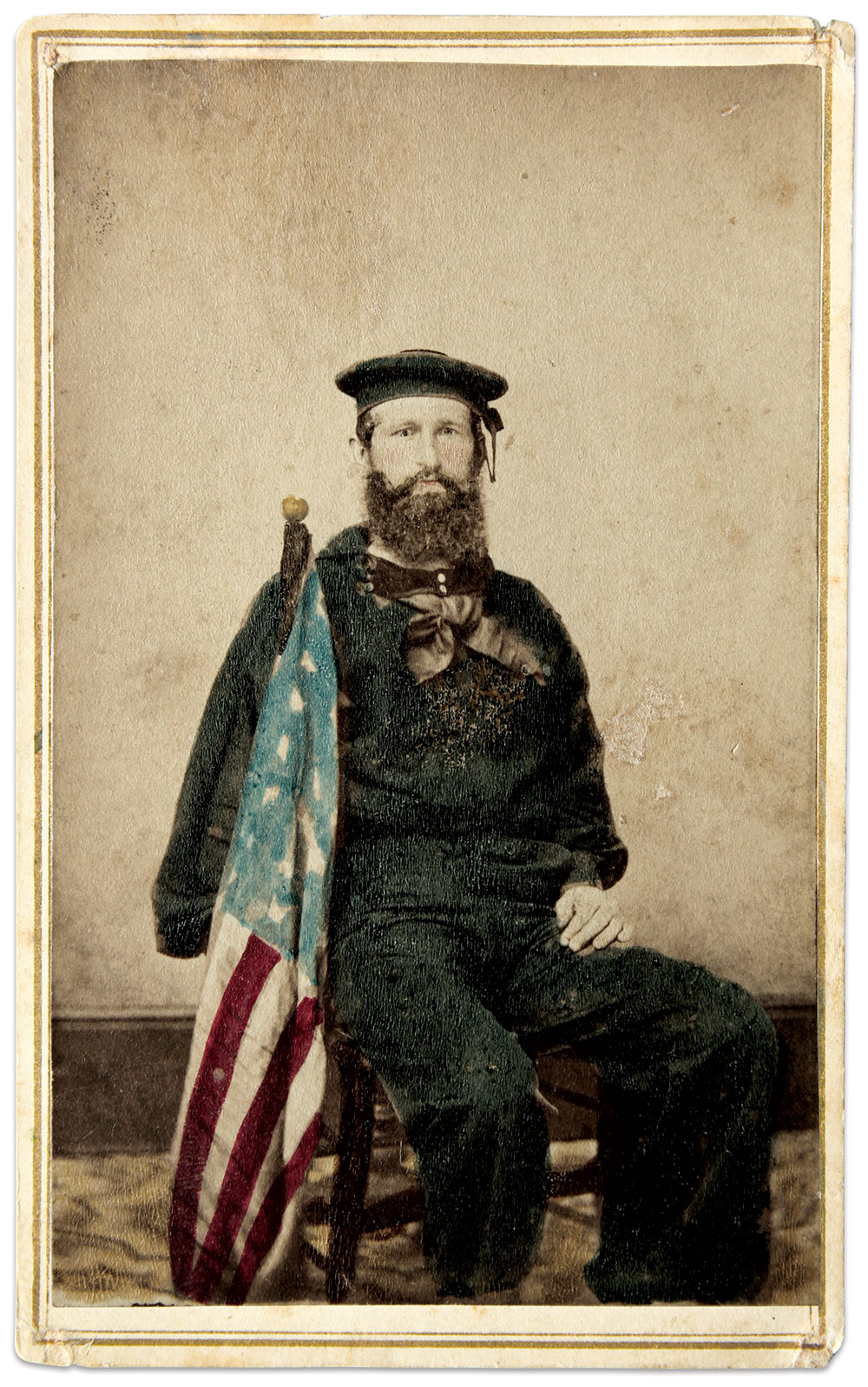

The proximity of the flag to this bluejacket’s empty sleeve tells a story of sacrifice for country and Constitution. 1,710 Union sailors suffered non-mortal wounds during the Civil War.

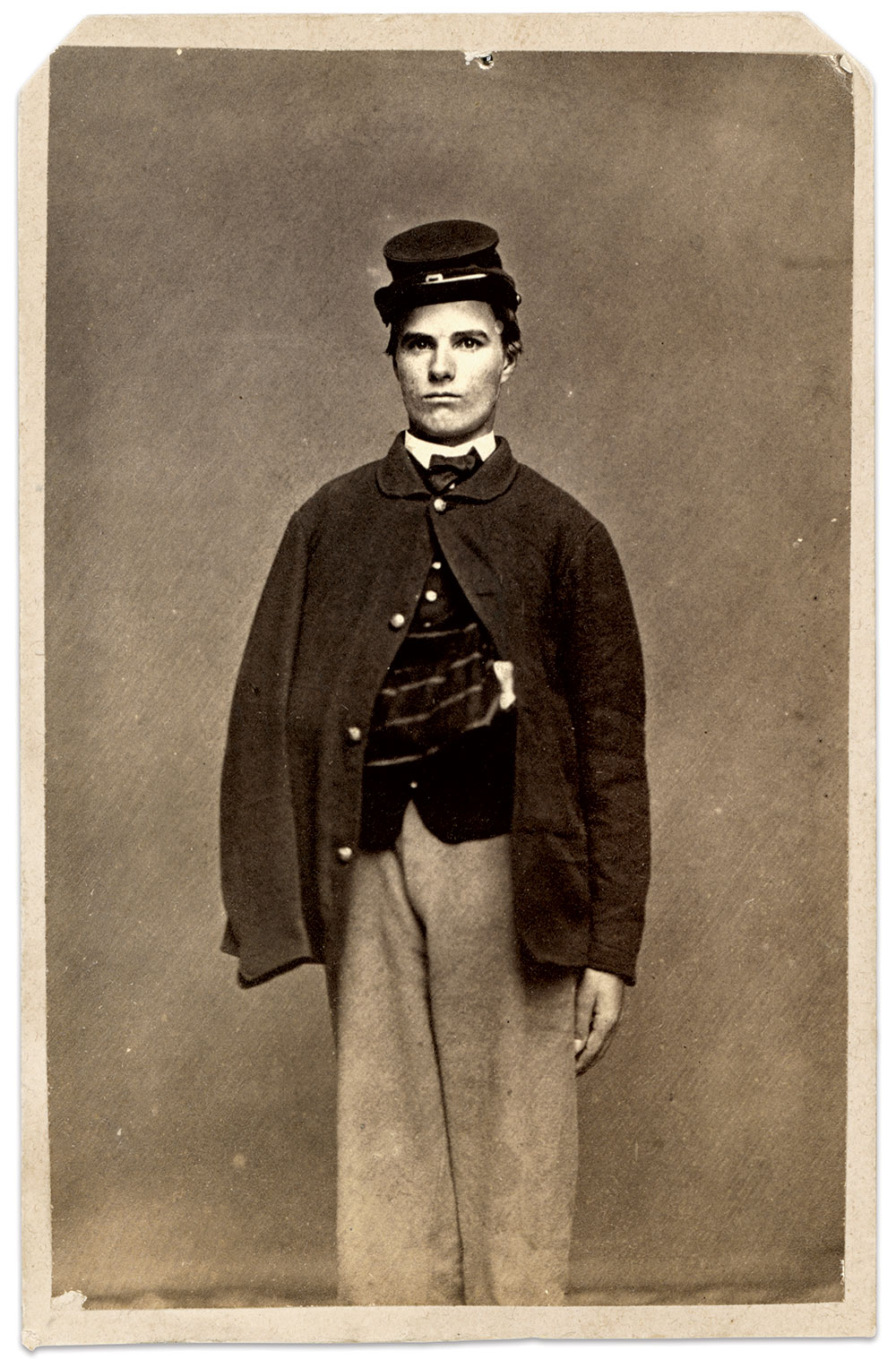

This federal soldier with an empty sleeve neatly pinned to his jacket holds a cap with a wreath and unreadable numbers in the center.

The story behind the empty sleeve on the jacket of this unidentified enlisted man in the Veteran Reserve Corps is lost in time. The Wisconsin photographer’s imprint on the back of the image suggests he hailed from the state or was stationed there. Both scenarios may be true.

The folds of the empty sleeve on the coat of this unidentified federal first lieutenant suggest surgeons amputated his left arm at the shoulder. About 5.5 percent of upper body amputations occurred at the shoulder, according to a study by the U.S. Medical Corps.

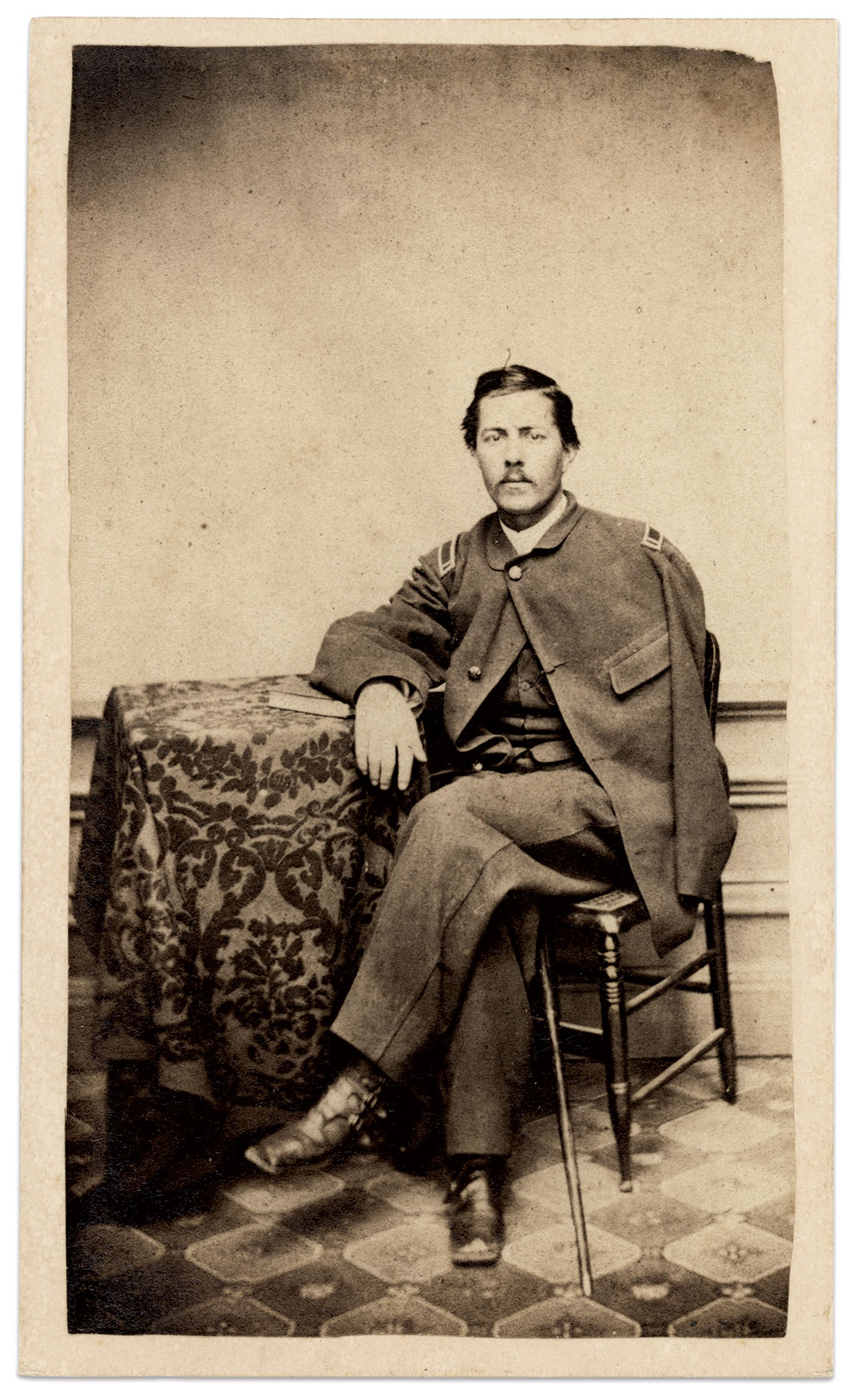

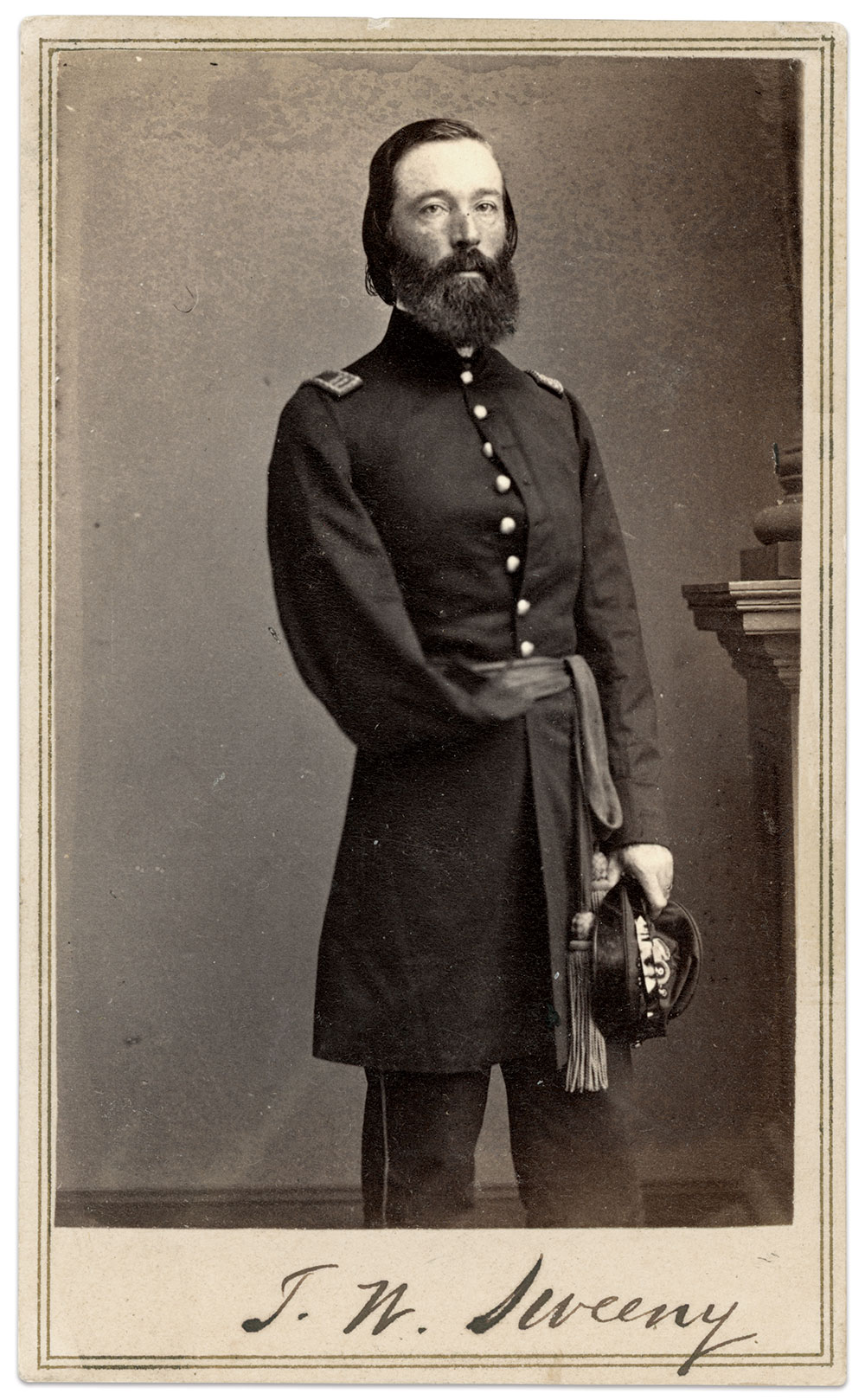

Some soldiers carried visible wounds from other conflicts when they became involved in the Civil War. Irish-American officer Thomas William Sweeny (1820-1892) falls into this unique group. He earned the nom de guerre “Fighting Tom” for courage during the Mexican War, where he suffered a wound at the Battle of Churubusco that resulted in amputation. He remained in the army and is pictured here as a captain of the 2nd U.S. Infantry in 1861, when he played a key role in military affairs in Missouri that helped keep the state in the Union. Sweeny went on to become colonel of the 52nd Illinois Infantry and led his regiment at Fort Donelson. He commanded a brigade at Shiloh, suffering and surviving multiple wounds in the battle. Elevated to division command, he famously got into a fistfight with his superior officer, Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, during the Atlanta Campaign. Sweeny ended his war service as a brigadier general, became involved in the Fenian Invasion of Canada, and retired from the U.S. Army in 1870.

This Union officer missing his sword arm appears to be a first lieutenant. A handkerchief is pokes out of a pocket of his private purchase jacket and the quatrefoil design on his cap without insignia may be ornamental. About one-third of all upper body amputations involved the arm, according to a statistical study by the U.S. Medical Corps.

Is it the skill of the photographer or the sitter's ability to connect comfortably and directly through the lens that resonates with viewers? The precise focus on the seam of the dangling empty sleeve tells part of his war story and his sacrifice for the Union cause.

This soldier with an empty sleeve pinned to his coat wears the sky blue uniform of the Veteran Reserve Corps, originally known as the Invalid Corps. The trim on his coat is unique. Bret Schweinfurth, an authority on the VRC, owns two images of soldiers in similarly-trimmed dress. Both served in the VRC out of Boston. The photographer’s location, Brattleboro, Vt., home to a military camp and hospital during the war, may offer a clue to his identity. Company G of the 13th VRC was organized there on Aug. 11, 1863. The lack of a revenue stamp on the back dates this portrait before September 1864. The 13th mustered out of service in late 1865.

At Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, gunshot shattered the lower third of 1st Lt. Jacob Thompson Zug’s right arm as he led his Company H of the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry. A surgeon amputated the mangled limb. This was the second time the peacetime clerk landed on the regiment’s casualty list—months earlier on Virginia’s Peninsula, Confederates captured him at Gaines’ Mill. He rejoined his company for the Antietam Campaign. Zug received an army discharge in June 1863. He made his home in Carlisle, Pa., where he prospered in business—a bank, a gas and water utility, a manufacturer, a printing firm and an insurance company. Consumption ended his life in 1883 at age 44. He left a wife and three children behind. “He was a truly good man, of sterling worth, and a kind and good friend,” noted one writer.

Union warships fired on the formidable defenses of Vicksburg, Miss., on June 28, 1862, in an attempt to capture the city. Though the attack failed, the Union vessels successfully ran the enemy batteries at a cost of 45 casualties, including Master’s Mate Howard Fenwick Moffat of the sloop-of-war Richmond, who suffered a wound after an 8-pound solid shot struck his upper left arm. Surgeons amputated the mangled limb. Born Thomas Howard Moffat, he changed his name for reasons unknown. Moffat joined the Navy in 1860. Following his wound, he recuperated at Mound City, Ill., and Brooklyn, N.Y., where his family lived. Moffat remained in the Navy and retired as an ensign in 1873. He went on to become a sailor on the Finger Lakes and died in 1892 at age 55.

Double amputees

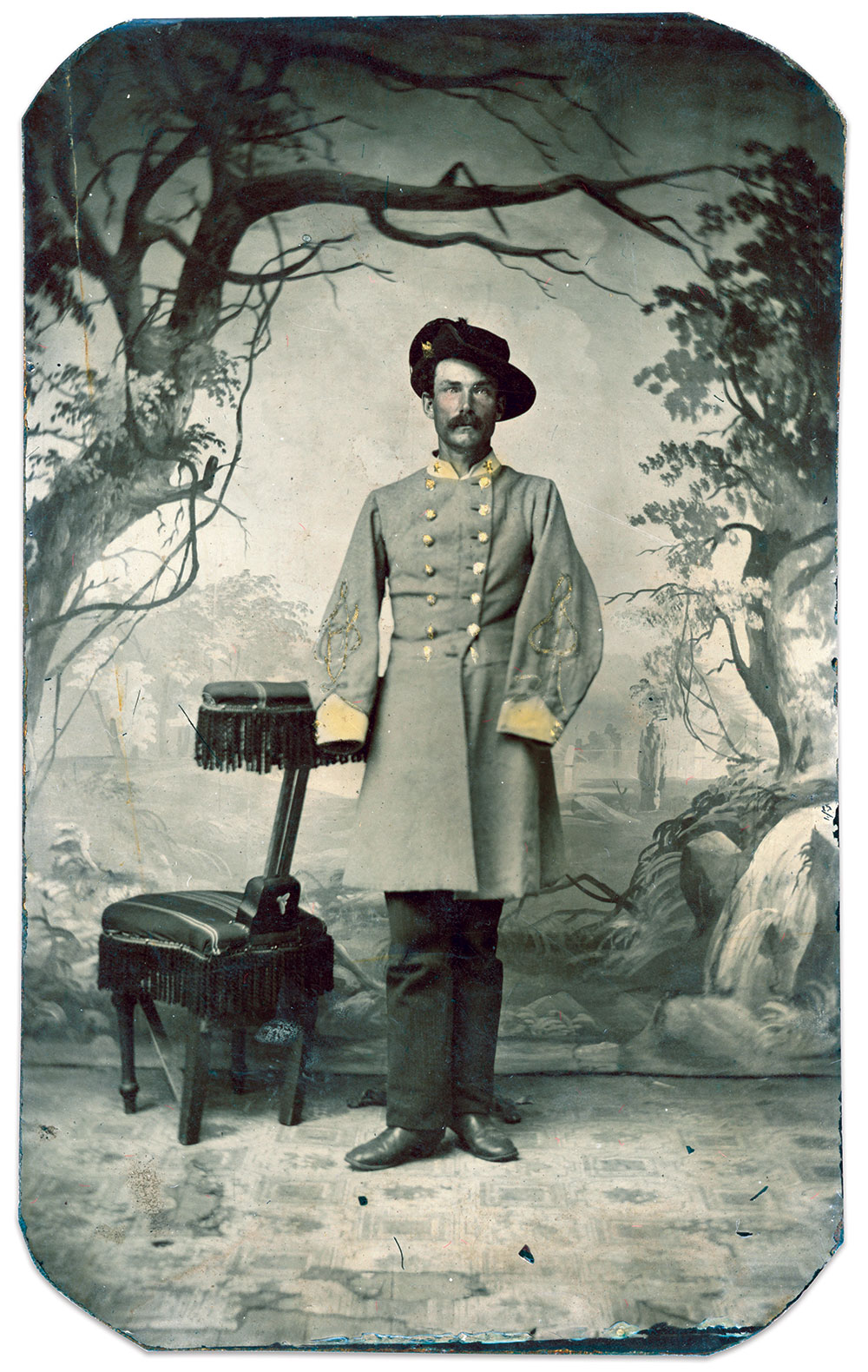

An armless Confederate major wearing a plumed hat stands in front of a background painting of a verdant landscape. He may have posed for this portrait just after the war. His name and origin story are currently unknown.

The 12-pound solid shot, or one like it, upon which the hand of this Union soldier rests may have caused him to lose both legs below the knee. This image, reproduced in The Image of War: 1861-1865 series by William C. Davis states this soldier may have a New Jersey connection. When owner Buck Zaidel purchased the image, the seller provided a provenance to the 91st Pennsylvania Infantry.

The 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry fought its first battle on June 1, 1862, at Fair Oaks, Va. Casualties included Pvt. William Sergent, wounded in both arms and his nose. Surgeons amputated his left arm on the battlefield, and the right in a hospital. Transported to Knight Army Hospital in New Haven, Conn., Sergent spent the next two-plus years recuperating. He’s pictured here, with angled face and shortened sleeves on his jacket, early in his recovery, and later, with a fleshier face and wearing a greatcoat with the cuffs of the sleeves pinned to the shoulder. Sergent mustard out of the 53rd in November 1864 and spent time in and out of Soldiers’ Homes before he succumbed to consumption in 1871 at age 27.

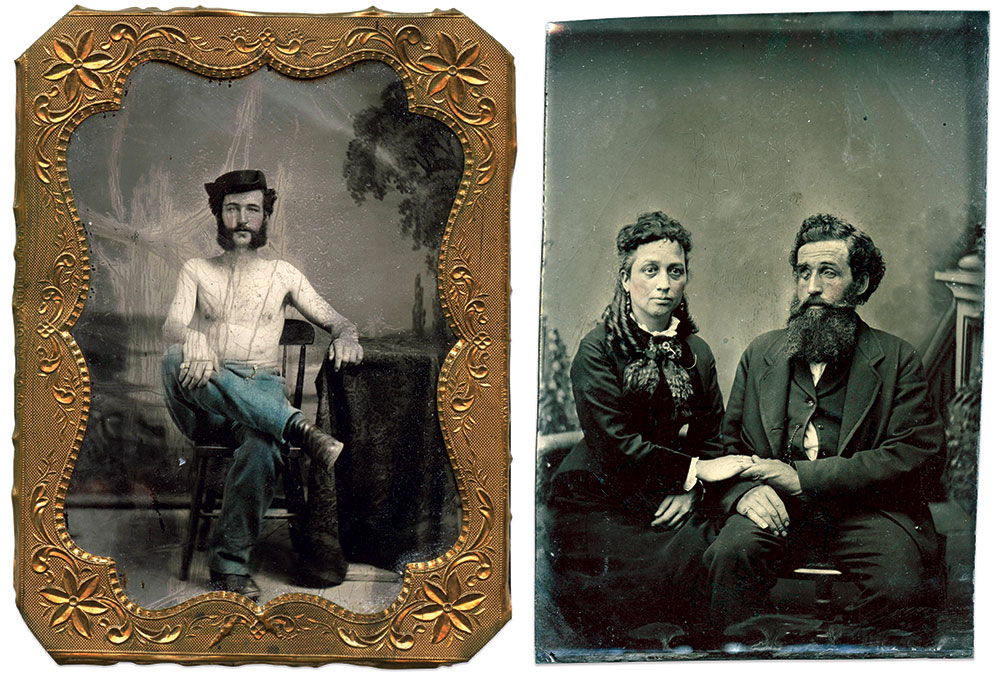

A cannon blast of grapeshot tore through the lower legs of Corp. Michael Dunn during the Battle of New Hope Church on May 25, 1864. Carried to safety by his comrades in the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry to the vicinity of Dallas, surgeons amputated his left leg, then the right. Over the next year, Dunn, a native of Ireland, endured operations to treat gangrene and other infections. He was not a candidate for prosthetics due the shortness of his stumps. Dunn is pictured here in uniform, wearing a small, cloth 20th Corps badge with his regimental number in the center. In one portrait he sits in a wheelchair, and, in the other, he poses with wife Sarah, whom he had married while on furlough before his wounding. Dunn’s injuries never fully healed, and doctors attributed them as the cause of his death in 1877 at age 44. Sarah and five children survived him.

Arm injuries

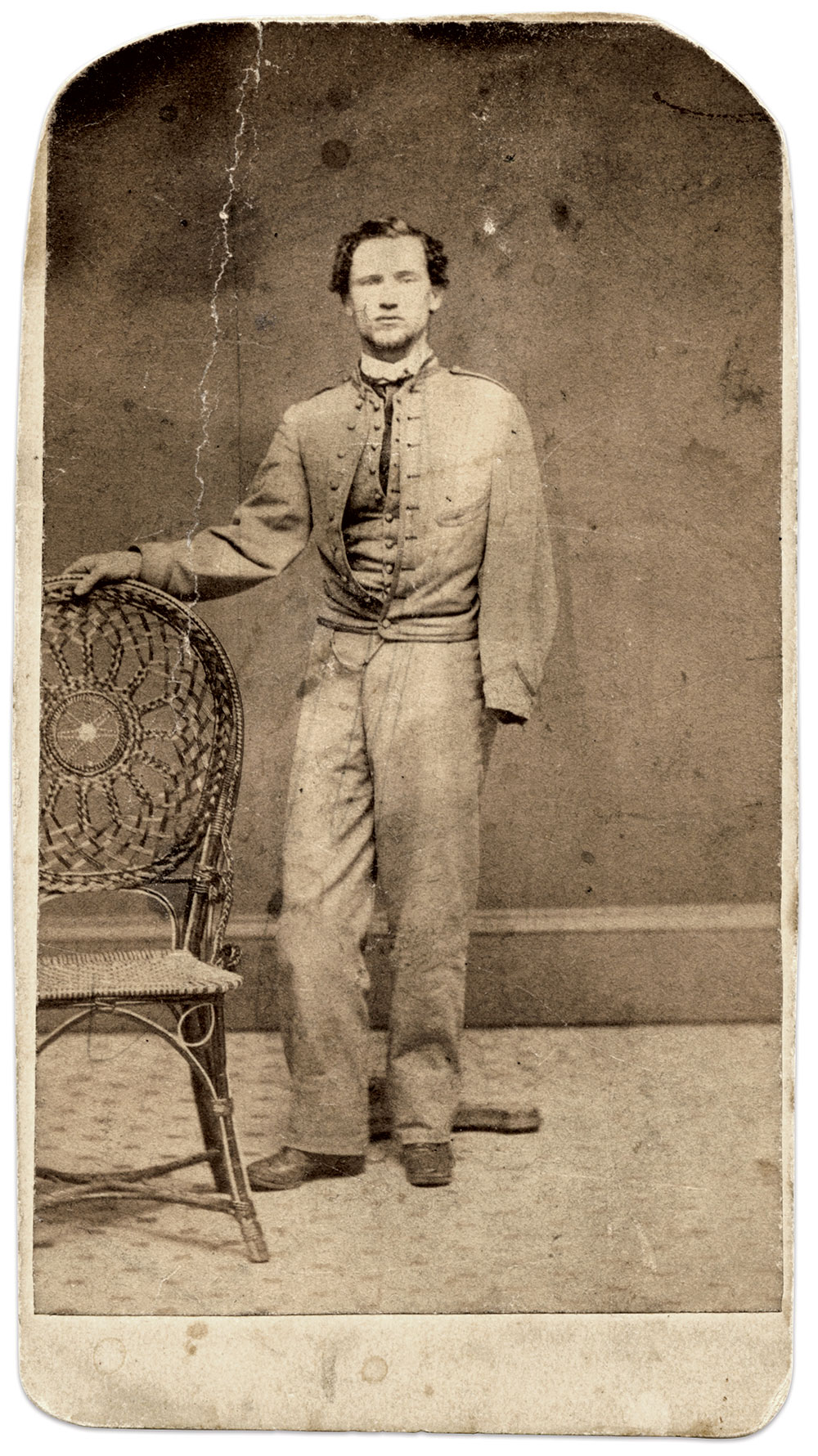

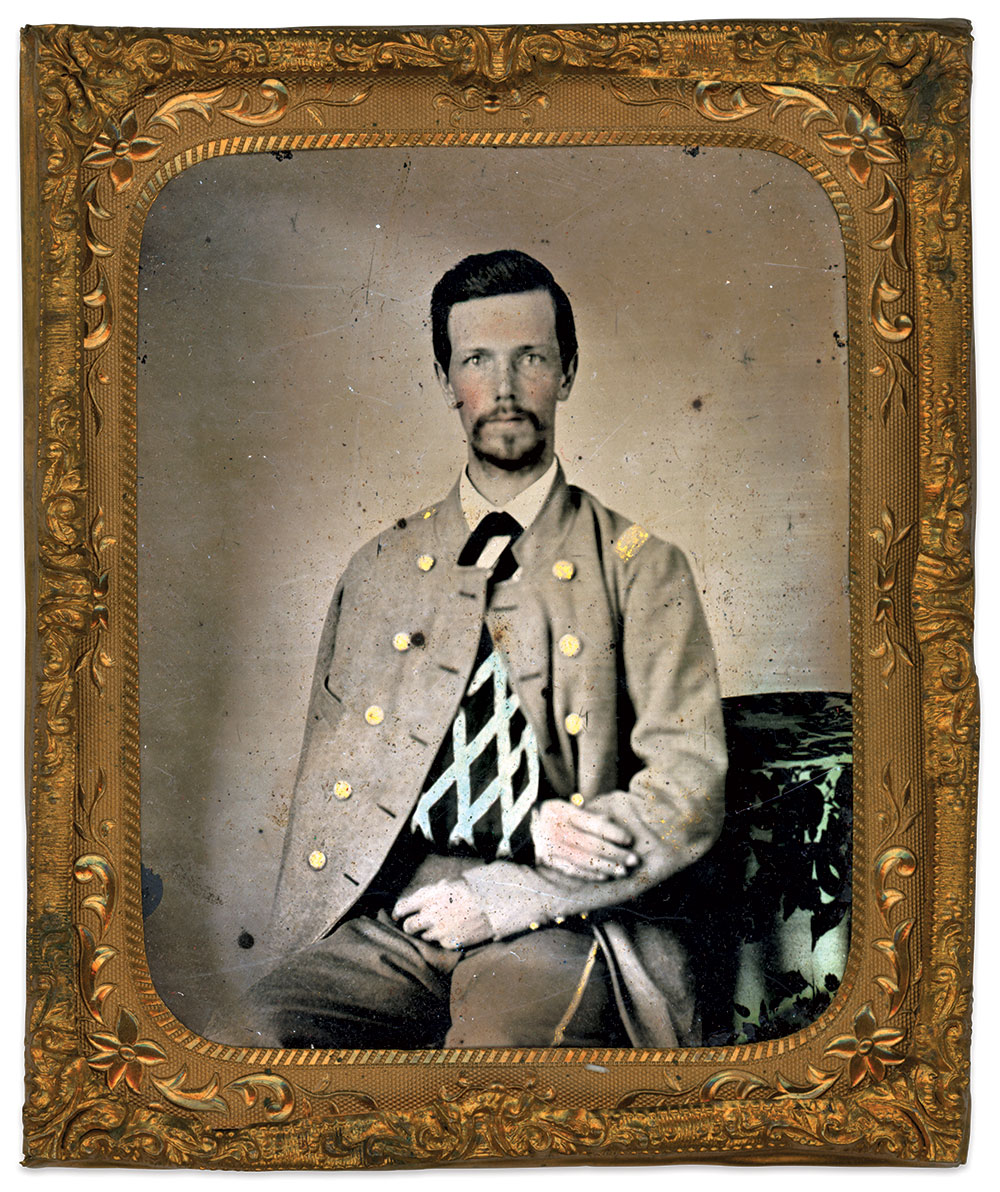

At Manassas on July 21, 1861, the 4th Alabama Infantry held their position for an hour or more, repulsing multiple enemy assaults and taking a beating as brother regiments around them melted away. As the firing intensified, Union lead tore into the regiment’s colonel, leaving Lt. Col. Evander McIver Law (1836-1920) in command. By this time the attacks compleled the Alabamians to flee. Law, on his mare, darted among the shattered ranks to stem the tide. He kept at it until a bullet tore into his left arm near the elbow and toppled him from his horse. Law got to his feet and kept pace with the retreat, blood streaming along his forearm and fingers. Meanwhile, Sgt. Maj. Robert Thompson Coles spotted Law’s mare and grabbed the reins. Coles helped Law on to the horse and ride for treatment. The remnants of the 4th later rallied and supported Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s memorable defense that earned him the nom de guerre “Stonewall.” Law is pictured here during his recovery. He returned to the regiment in October, his injured arm effectively useless. Celebrated as a hero, one newspaper correspondent wrote of Law and his Alabamians, “He will lead them anywhere, that the honor of battle can be plucked.” Law went on to brigade command, temporary commanded a division at Gettysburg after the wounding of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood, lost the confidence of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, and suffered a second war wound at the Battle of Cold Harbor in 1864.

A cavalry trooper stands with his right arm in a sling, his name and the cause of his injury lost in time. He poses in a gallery of daguerreian pioneer James Keagy in Chambersburg, Pa. Organizers raised the state’s 1st Cavalry in the town in 1861. At least two other regiments recruited men from the area, including the 2nd and 21st. Chambersburg is remembered for being burned in July 1864 by Confederate raiders led by Brig. Gen. John McCausland.

During the May 11, 1864, Battle of Laurel Hill, Va., a bullet tore into the back of the right hand of Pvt. John Follen of the 39th Massachusetts Infantry, fractured the long bone leading to his index finger, and lodged in his flesh. A surgeon removed the bullet two weeks later at the First Division General Hospital, located at the Mansion House Hotel, in Alexandria. On July 2, doctors declared him a convalescent. It may have been about this time that he walked three blocks to the photo studio operated by N.S. Bennett to have this portrait of him made with his bandaged hand in a sling. He survived the war and died at about age 83 in 1919.

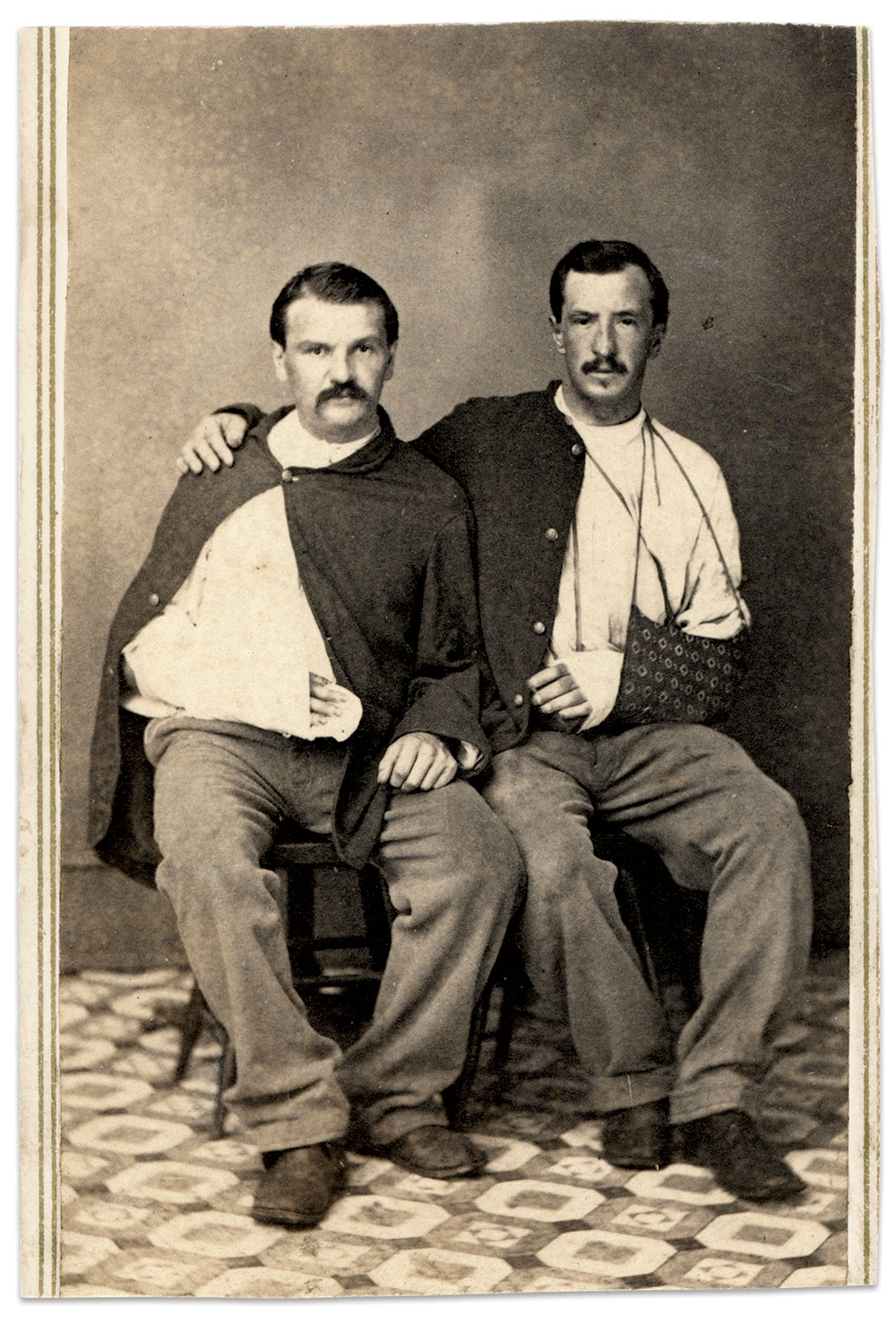

Two Union enlisted men turned back their sack coats to reveal their bandaged arms. Both soldiers, their names currently lost in time, likely suffered wounds in an Eastern Theater battle and after initial treatment were transported to New York City, where they sat for this portrait.

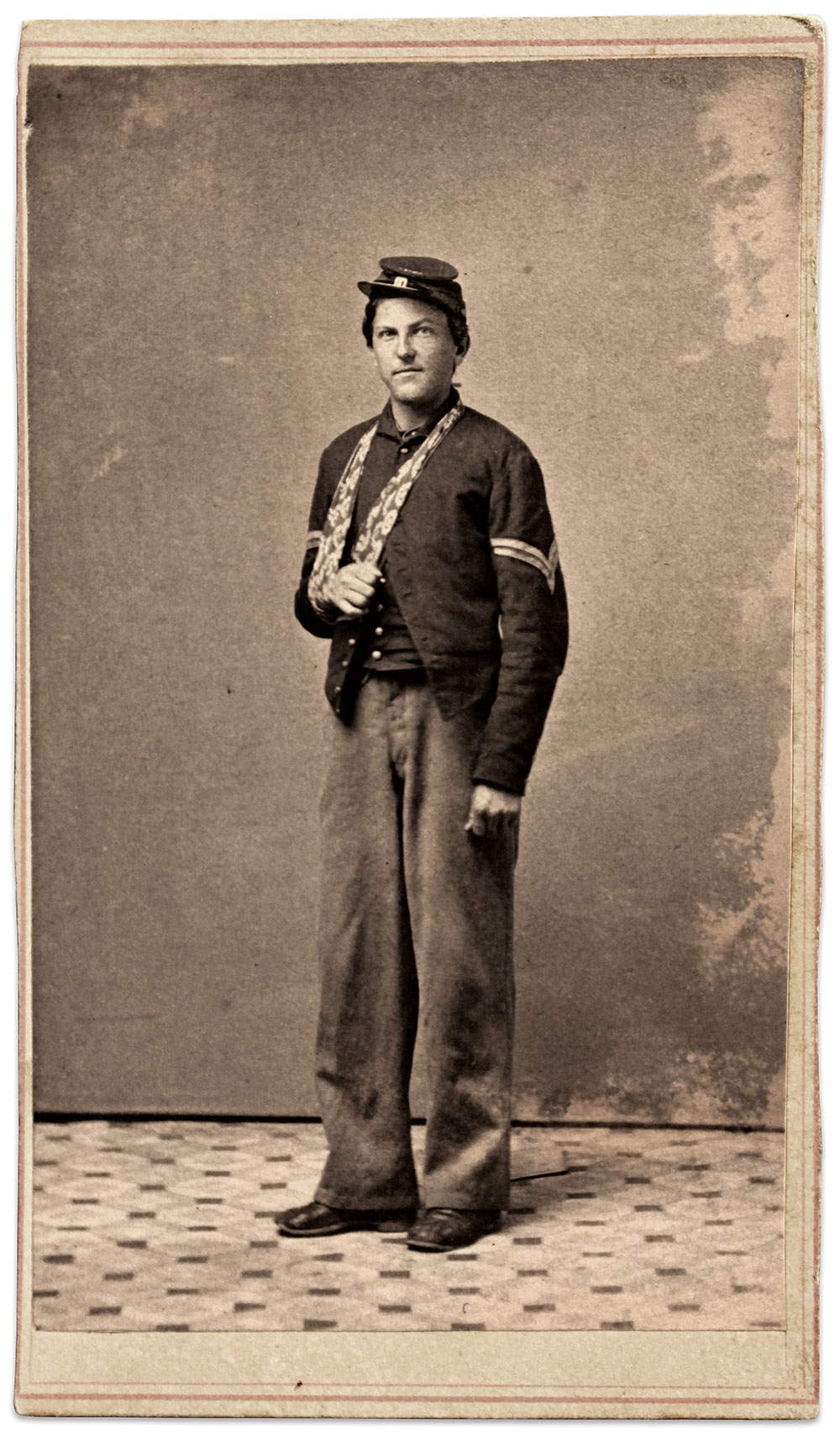

A sling fashioned of boldly-patterned cloth supports the injured right arm of this Union corporal. It is easy to imagine this portrait and others like it being sent home by soldiers to concerned families and friends to let them know that they were on the mend—though full recovery was never certain.

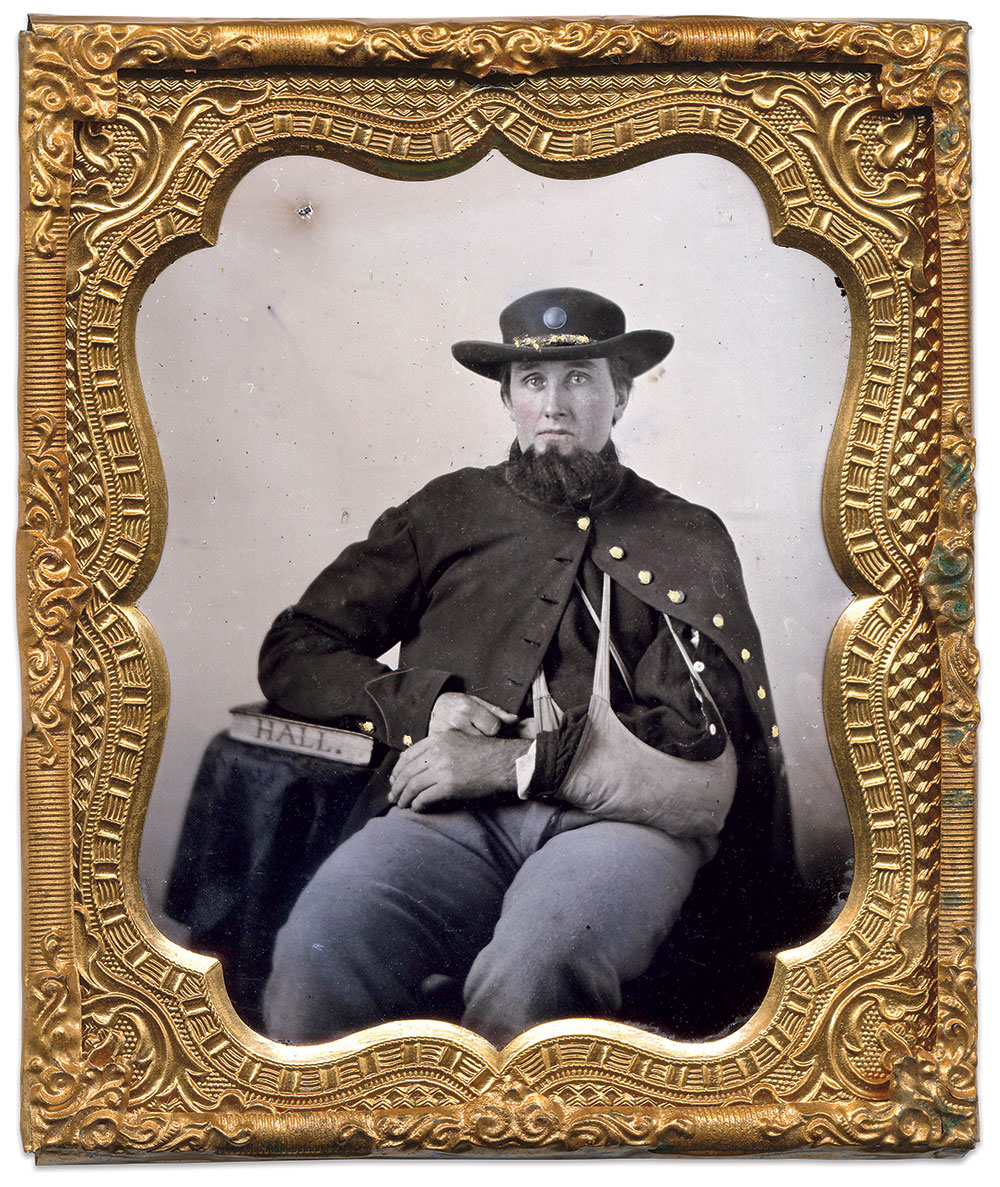

This soldier wears his frock coat draped over one shoulder exposing his wounded arm, supported by a sling. His blue-tinted hat insignia indicates his connection to the Third Division of the Army of the Potomac’s 1st Corps. The photographer’s imprint on the fore edge of the book upon which he soldier rests his uninjured arm. Considering the lateral reverse effect common to hard plate images, the photographer would have had to have written his name backwards on the book in order to be read by the viewer.

Leg injuries

The name of the clean-shaven, wheelchair-bound soldier is lost in time. Aside from his obvious leg injury, there is an important clue that might help put a name to his face—the heart-shaped badge attached to his cap. The badge connects him to the 24th Corps, which was part of the Army of the James. This corps participated in the Petersburg and Appomattox campaigns.

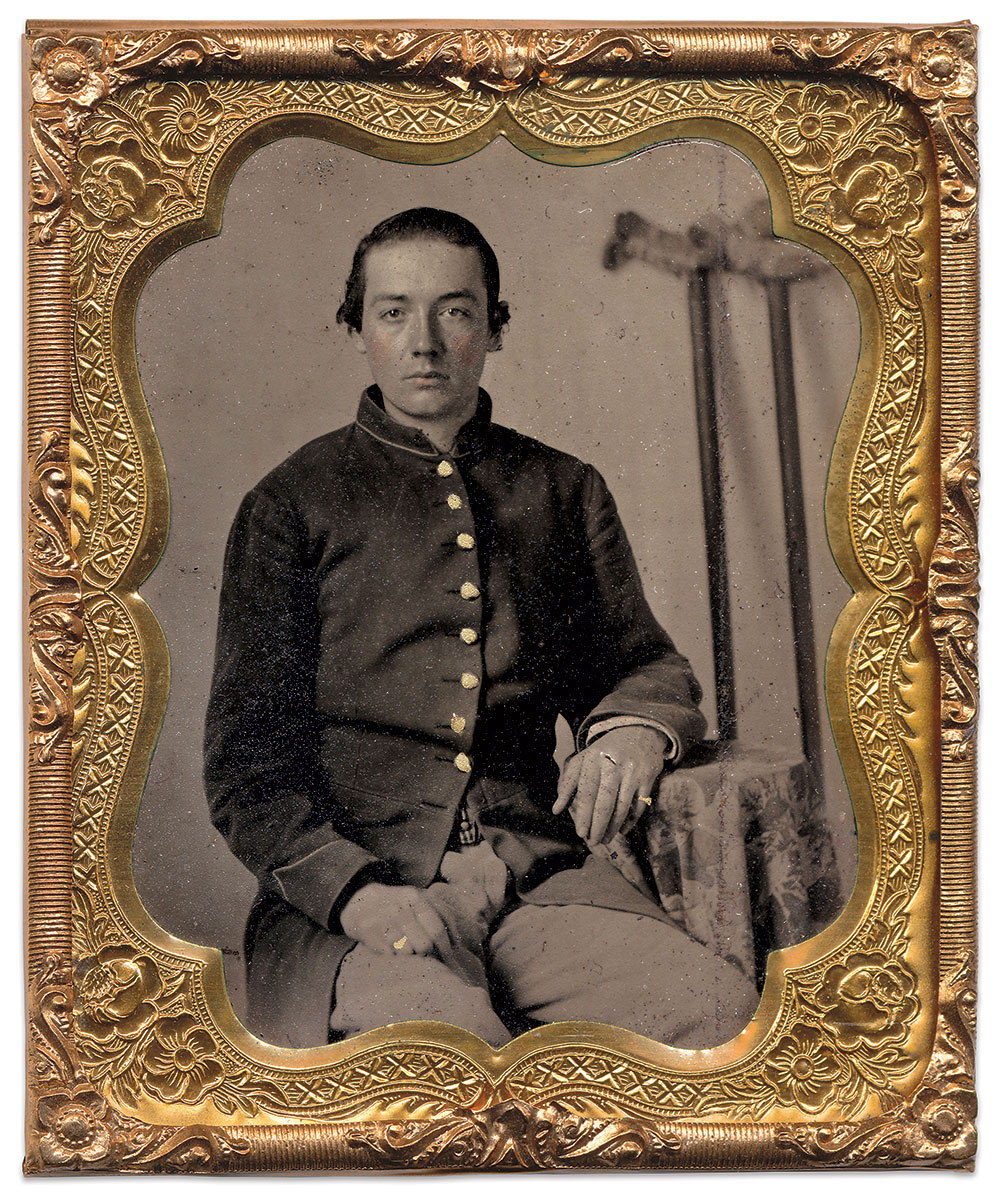

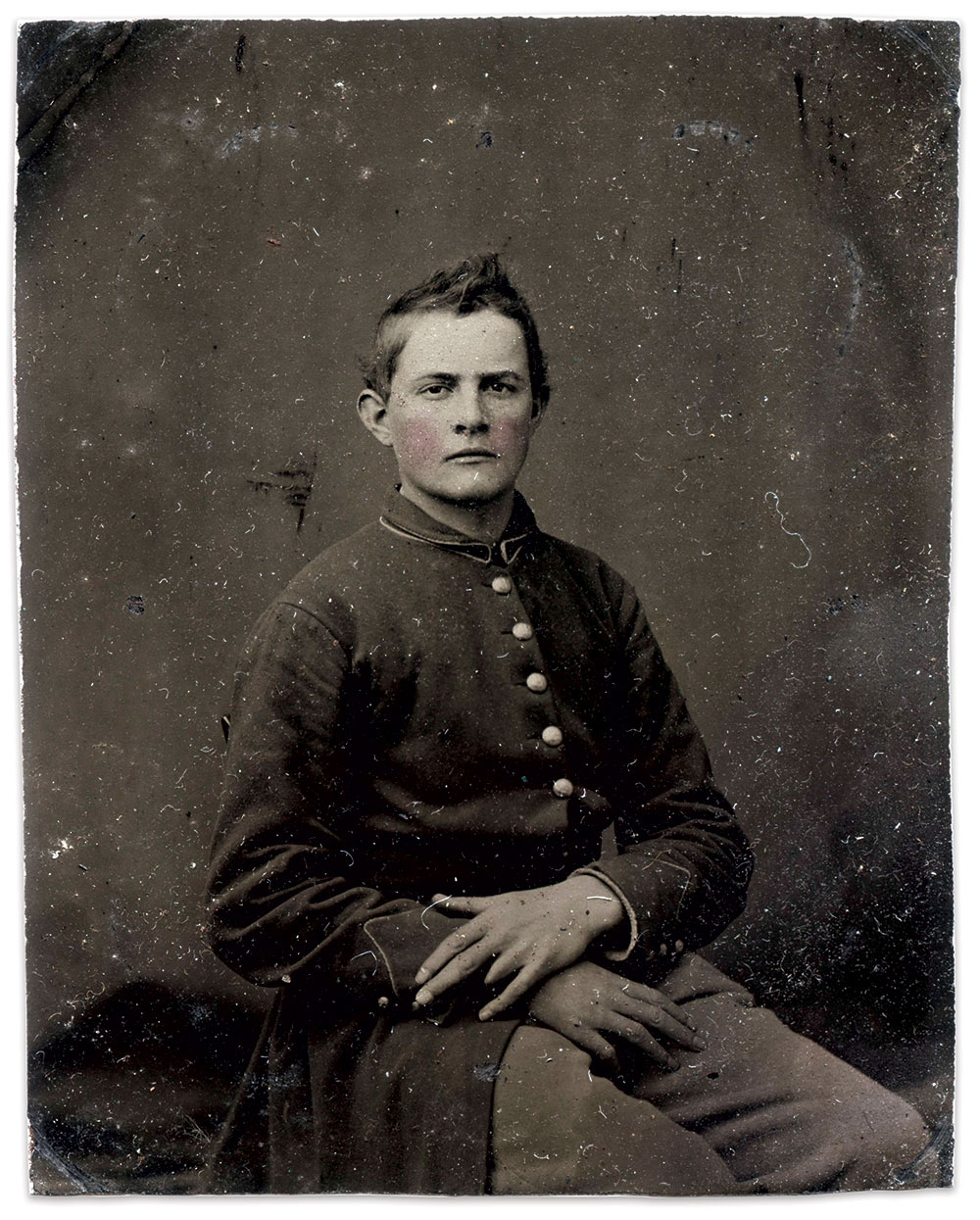

The pair of crutches behind this unnamed Union enlisted man is a poignant reminder of human fragility in times of war.

At Stones River, half the officers of the 13th Louisiana Infantry became casualties, including Capt. John Martin King. Wounded in his right leg, Union forces captured him on the battlefield. A Union surgeon eventually amputated the limb. Released from imprisonment in September 1864, he joined the retired list in January 1865. This image, dated February 20, 1865, marks the end of his paper trail. His fate is currently unknown.

Fingers and eyes

A federal soldier rests his right hand on the cuff of his coat. The shadow cast by the hand highlight the missing ring finger at the first knuckle.

Three fingers on the left hand of this Union soldier are missing. He holds a black-dyed straw hat in his right hand, and wears a sack coat and non-regulation vest. He posed for his likeness in the studio of noted Black photographer James Presley Ball (1825-1904).

During the ill-fated charge at Petersburg, Va., on June 18, 1864, the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery suffered significant casualties, included William Berry (1841-1895). A ball struck his left eye and traveled downward, fracturing his lower jaw before it exited in front of his left ear. Berry started the war in 1862 with a nine-month enlistment, and rejoined the army as a heavy artilleryman six months before his wounding. Hospitalized in Washington, D.C., and Augusta, Maine, he received a discharge in September 1865. He became a farmer in Lisbon Falls, married, and had a daughter. He died from cancer at age 54.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Wounded Warriors: Slings, crutches, and missing limbs are emblems of personal loss and patriotic sacrifice”

Comments are closed.