By Ronald S. Coddington, with images from the Dave Batalo Collection

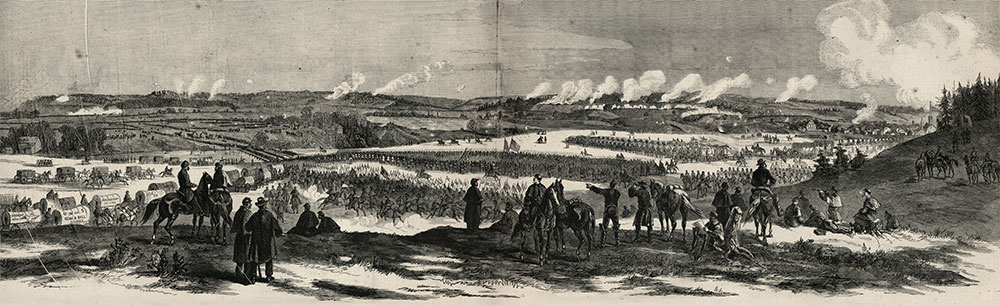

High anxiety consumed Lt. Col. Lewis Minor Coleman at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. As fierce fighting raged throughout the morning and into the afternoon, he and his battalion of reserve artillery were parked behind Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Corps on the southernmost section of the Confederate right flank.

Coleman awaited orders to join the fray as the rhythmic pounding of cannon, the ripping of musketry, and the shouts of men mixed with the smell of sulfur and drifts of gunsmoke, permeating the cold air and muddy backroads littered with the debris of wrecked cannon and lifeless horses.

An energetic, active man driven not by ambition, but by a desire to occupy positions that made the best use of his abilities, the 35-year-old Coleman’s tension level rose with every cannon boom.

Coleman was not a warrior by instinct. Family, friends, and acquaintances knew him as a peacemaker, a benevolent, modest protector who never sought the spotlight. A humble Christian who lived the Golden Rule, he placed spiritual growth at the center of his existence.

Lessons learned

These values had been evident from his earliest days growing up the eldest of six children at Chantilly, a homestead in Virginia’s Hanover County, just north of Richmond. One childhood story has it that a younger brother instigated a fight. When the brother noticed their mother, Mary, coming towards them, he fell on the ground in attempt to make Coleman appear as the aggressor. She whipped Coleman, and when he told her he hadn’t started the fight, she whipped him again for lying. He took the two beatings without revealing his brother’s intent to deceive.

Coleman barely knew his father, Thomas Burbage Coleman, a state assemblyman. He died before Coleman’s fifth birthday. Mother Mary soon remarried a physician, George Fleming. Perhaps because of the early death of his father, Coleman credited his mother with any goodness in his nature. She instilled in him discipline, organization, duty, and honor. Her instruction helped him control his quick temper.

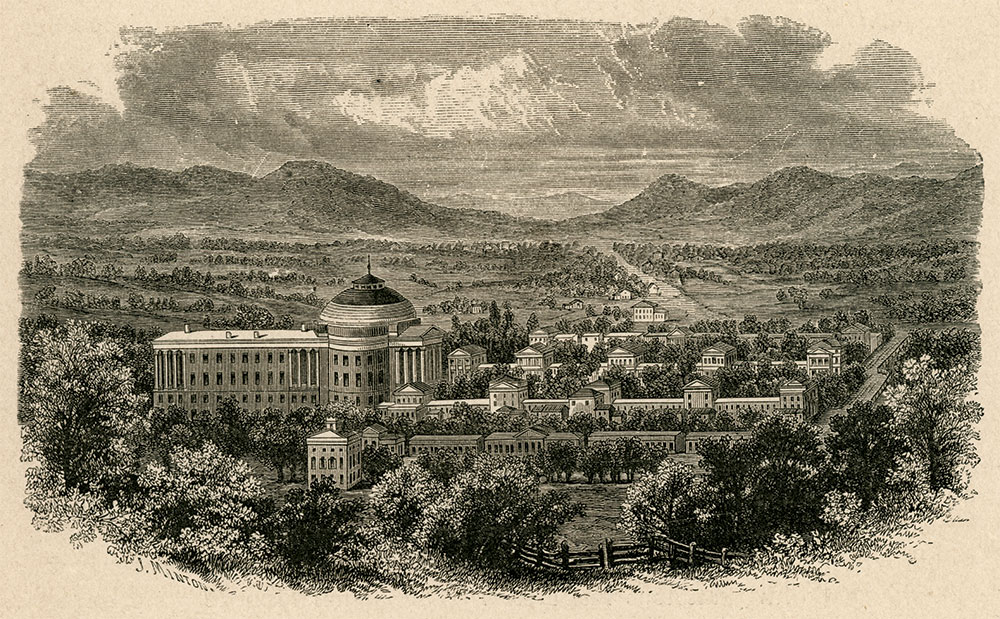

Coleman proved an above average student. He earned high grades at a local private school, and later at Concord Academy in neighboring Caroline County, an institution operated by an uncle. By the time he entered the University of Virginia at age 17 in 1844, one classmate recalled Coleman seemed older than his age, due in part to his depth of knowledge of so many subjects. He proved a sterling student, earning high honors and graduating two years later with a Master of Arts degree.

Coleman returned to his family at Chantilly, where his concern for spiritual well-being led him to become born again as a Christian in the Baptist faith.

Empowered by his experiences with church and university teachings, Coleman embarked on a career as an educator. He started as an assistant to his uncle at Concord Academy. When it closed in 1854, Coleman founded Hanover Academy. Five years later, in 1859, he passed ownership of the flourishing school to an assistant after he accepted a professorship of Latin and literature at the University of Virginia.

He and his wife, Mary Ambler Marshall Coleman, whom he had married in 1855, relocated to Charlottesville. Mary’s grandfather, John Marshall, a Founding Father, had served as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Coleman thrived in his new position. One writer credited him for raising the bar on quality on campus: “His students were found upon examination thoroughly prepared for the University course and took high rank in that institution. He thus too, in connection with worthy contemporaneous teachers, contributed much to elevate the grade of scholarship at the University itself, and to secure for it that high degree of popularity which drew a larger number of students to its halls than to any other college on this continent.”

The young Professor Coleman summed up his approach this way: “I try to do good and sometimes trust and believe that there are those whose hearts and lives will be improved by my teachings, and whose aspirations will be excited for high and holy endeavors.”

His efforts to educate extended to his church. When a local Sunday school for Black children and adults lost its teacher, administrators invited Coleman to lead the class. He reluctantly accepted the post, and poured his heart into the work. The writer who shared this anecdote did not mention whether any of the people enslaved by Coleman—11 men, women, and children ranging in age from one to 35 in 1860—numbered among his pupils.

Professor Coleman goes to war

Thousands of cheering men and handkerchief-waving women crowded around the train depot in Charlottesville during the evening of April 17, 1861. United in secession following news that Richmond legislators had ratified the ordnance severing its ties with the Constitution, the throngs offered their support and solidarity to four militia companies headed to Harpers Ferry to occupy the U.S. arsenal. University students filled the ranks of two companies, the Sons of Liberty and the Southern Guard, and local boys formed the Monticello Guards and Albemarle Rifles.

The crowd responded enthusiastically as campus and civic leaders stirred soldiers and bystanders with patriotic addresses. About 10:30 p.m., another company, the West Augusta Guard, arrived by train from nearby Staunton, swelling the number of volunteers.

The Charlottesville companies boarded the train as clergymen mingled amidst the volunteers, bestowing God’s protection over them. The crowds called out “God bless you,” “goodbye,” and “be victorious” as the locomotive pulled out of the station with its precious cargo.

Professor Coleman attended this event, cheering the boys on. He supported the cause, joining the majority of Virginians and others across the Southern states who believed that they owed their allegiance to God and home state after Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party had violated and distorted the original intentions of the Constitution.

A biographer stated that Coleman returned home, where “throwing himself upon a sleepless bed he exclaimed; ‘I am so sorry I did not make a speech to those noble boys. The poor fellows called me out too. Some of them I may never see again, and upon the verge of so important a step I failed to urge upon them the performance of their whole duty in this matter, and especially to remind them of their accountability to God. How I regret that I did not speak to them.’”

Coleman had no desire to be a soldier. He relished his career as a professor and loathed the idea of camp and campaign, of war and fighting, of death and destruction.

The Charlottesville companies returned less than two weeks later, their mission complete, to a hero’s welcome. With the eight-star flag of the new Confederate States of America floating over the iconic dome of the campus rotunda, the boys marched to the music of cornets and cheering crowds. They arrived at the residence of the faculty’s chairman, Dr. Socrates Maupin, who commended them for promptly stepping forward to their country’s aid. He also offered a piece of advice, for the benefit of them and the university: Don’t enlist in the army as a single company. Instead, join different companies across the state to avoid being wiped out in a single battle that would deprive the university and Virginia of their talents.

Coleman had no desire to be a soldier. He relished his career as a professor and loathed the idea of camp and campaign, of war and fighting, of death and destruction. But as the days passed, and he observed his students, friends and family join the army, his sense of duty and honor pulled him to take an active role in fighting for his beliefs.

The turning point—the moment when he knew he had to set down his pen and pick up the sword—came after news of the tremendous victory in the war’s first major battle at Manassas.

His graphic pictures of the perils of the country and of the methods by which it might be delivered from oppression and rendered free and prosperous, often drew tears from eyes unaccustomed to weep.

Days later, Coleman left Mary and their infant son, Lewis, Jr., for Hanover County, armed with a captain’s commission, to raise an artillery company. The address he never delivered to students in Charlottesville manifested itself as he sought volunteers. A biographer recalled, “he appointed meeting and made speeches like a trumpet blast. His graphic pictures of the perils of the country and of the methods by which it might be delivered from oppression and rendered free and prosperous, often drew tears from eyes unaccustomed to weep.”

Joined by his brother-in-law, Edward Watts Morris, and Hilary Pollard Jones, the principal of Hanover Academy, Coleman succeeded in his mission within a month. The new company, named in Morris’s honor, mustered into service with Coleman as captain and commander. Morris and Jones became his lieutenants.

Captain Coleman went to work with characteristic energy to educate himself on the arts of war. A fellow captain, Willis Jefferson Dance of the Powhatan Light Artillery, who had formed his company about the same time, recalled that Coleman’s early attempts to train his men were met by a few smiles as he clumsily translated what he had learned in instruction manuals to the drill field. But he got the hang of it soon enough and readied the Morris Artillery for field duty before Dance, who had a head start training his recruits.

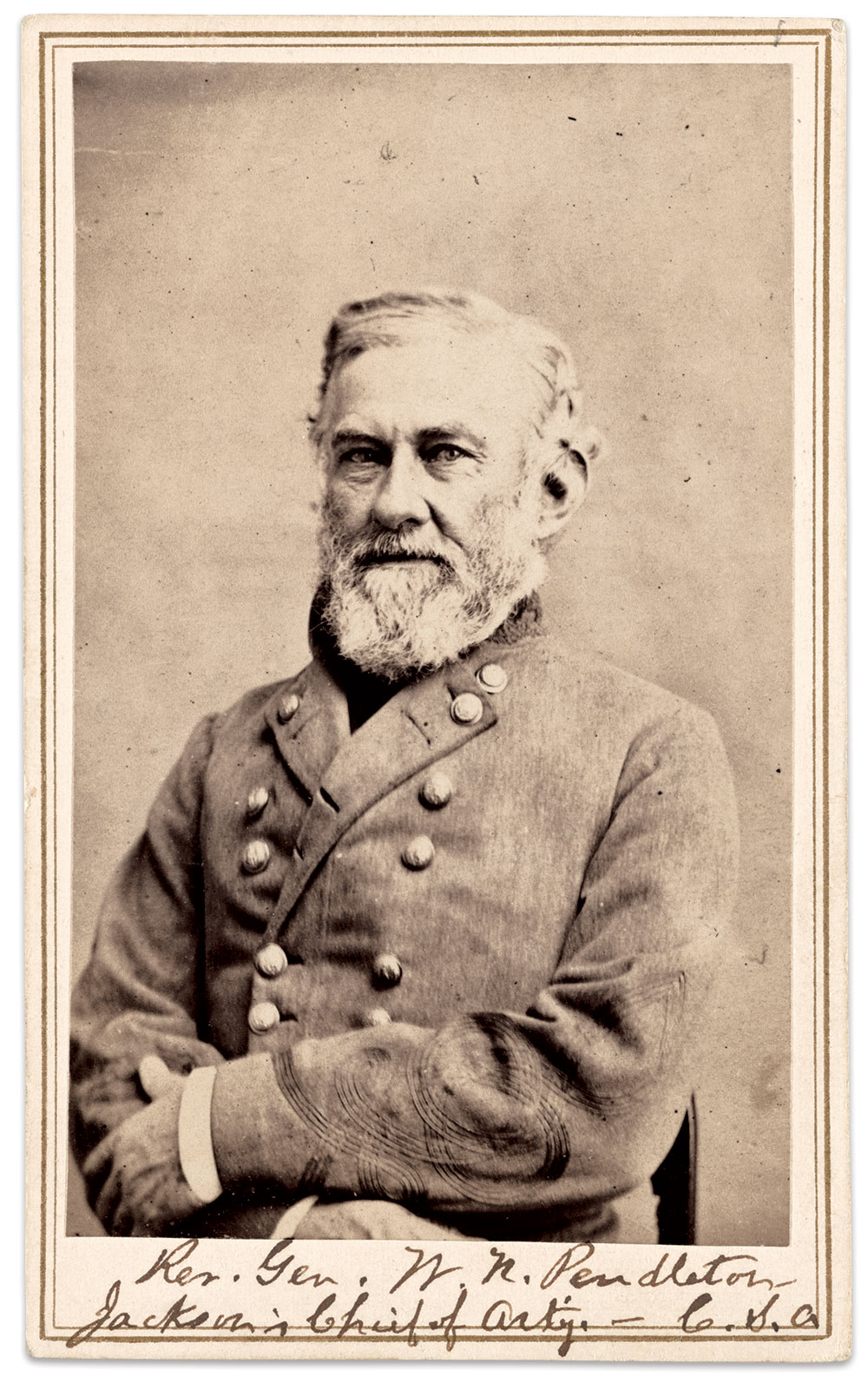

Coleman and his artillerists reported for duty to Col. William Nelson Pendleton. In the recent victory at Manassas, Pendleton had suffered minor wounds as Chief of Artillery to Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Pendleton assigned them to the Reserve Corps of Artillery.

The Morris Artillery went into action the following year. It participated in defensive operations against the Union’s Army of the Potomac, led by charismatic Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, as it marched along the Peninsula towards Richmond. During the Siege of Yorktown, Coleman faced his first combat—a test of any soldier’s courage. He reacted to hostile fire with “a perfect confidence and peace,” wrote a biographer. Coleman attributed his cool, calm demeanor in the heat of battle to God.

Meanwhile, in one of a series of reorganizations of the army to better function in a longer-than-anticipated war, Coleman received his major’s star. But a consolidation of independent batteries reduced the need for officers at his level, and he lost his command. Senior leadership, impressed by his performance, promoted him to lieutenant colonel of the 1st Virginia Artillery.

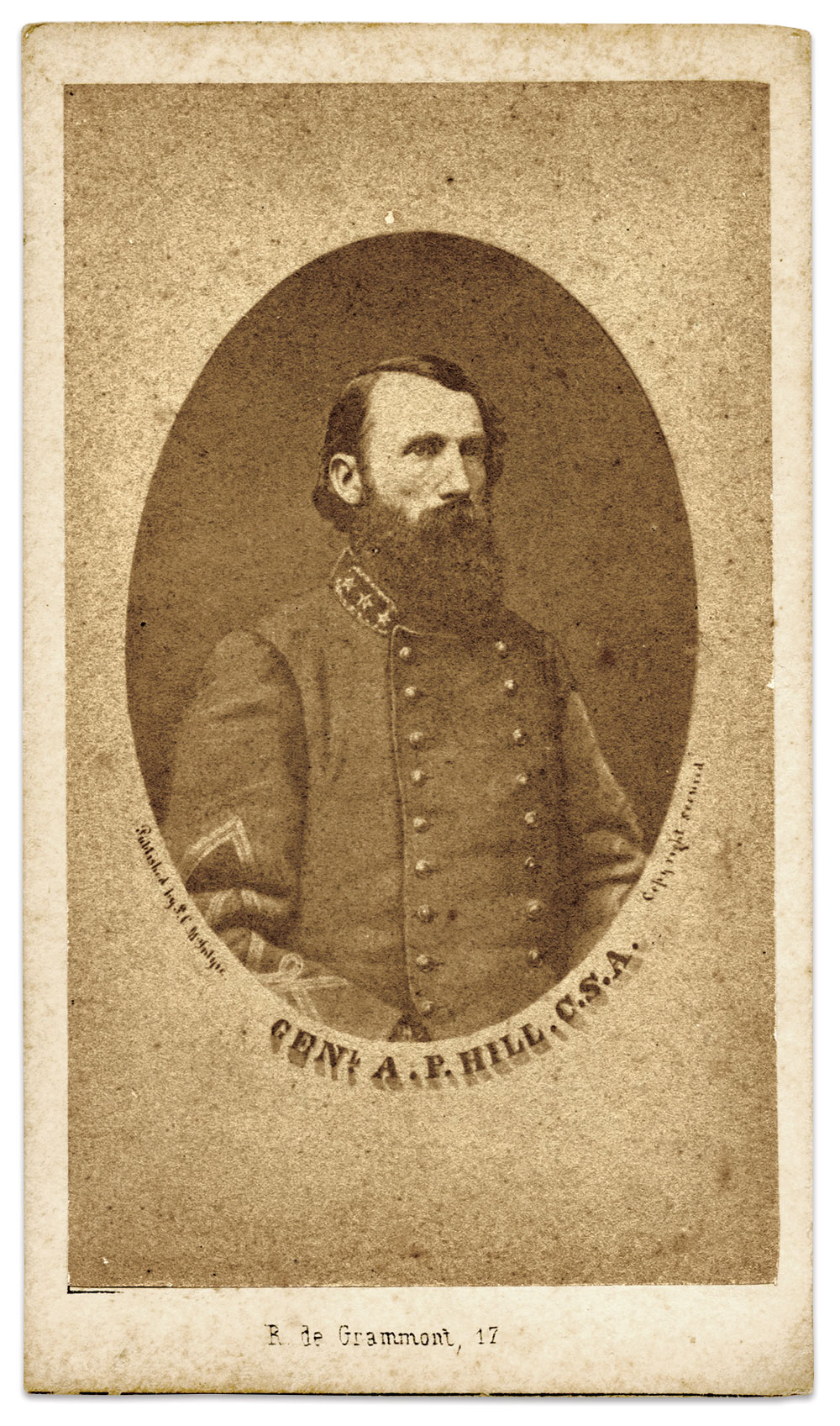

Assigned to Maj. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill’s Light Division, Lt. Col. Coleman served as Assistant Chief of Artillery to Col. Reuben Lindsay Walker, an 1845 graduate of Virginia Military Institute. During the culminating Seven Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign, Coleman commanded in the absence of Walker, who had fallen ill.

Following the successful defense of Richmond, the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Gen. Robert E. Lee, transferred Hill’s Division to Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Corps. Lee made the move to stop an open feud between the quarrelsome Hill and his superior officer, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet.

In the Shenandoah Valley during the summer of 1862, Walker returned to duty as Chief of Artillery and Coleman as assistant. As Hill’s Division and the rest of Jackson’s Corps joined Lee’s army on the Maryland Campaign, illness forced Coleman to remain behind.

Coleman departed camp on extended leave with grave misgivings about abandoning his duties as his men invaded the North. He left instructions with a brother officer to send for him if battle appeared imminent. Sometime later, while Coleman recuperated, someone knocked on the door of his home in the dead of night. Coleman, still seriously ill and barely able to walk across a room, assumed it was the call to battle. Wife Mary protested. But the caller had come on an unrelated matter, ending the alarm.

Weeks passed until Coleman regained his strength. He returned to his command before the Battle of Fredericksburg.

High anxiety at Fredericksburg

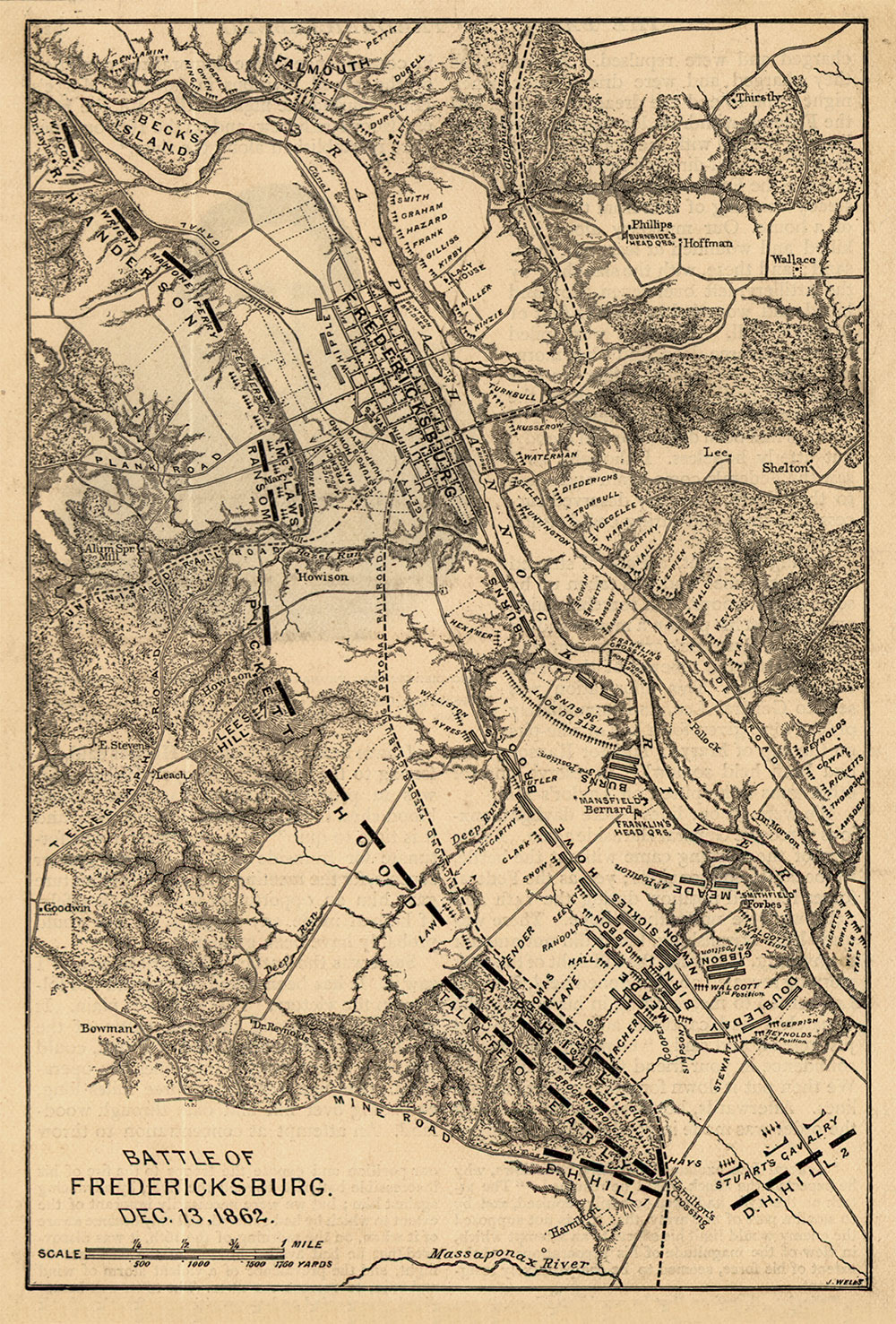

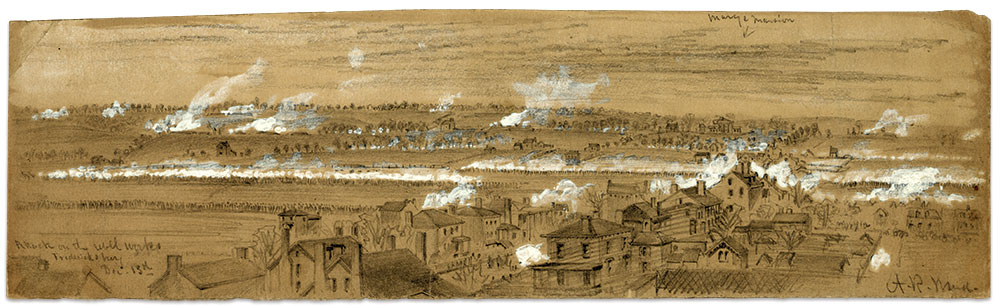

Prospect Hill anchored the southernmost section of the Confederate battle lines at Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. Engineers transformed its topography into a formidable artillery position of 14 guns, in coordination with commanders from Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Corps. Another 40 cannon were located in four clusters supporting Jackson’s infantry. More guns, including Coleman’s artillery, remained in reserve on nearby Forest Hill.

On the opposing side of the field of battle, enemy artillerists readied for action. About 11 a.m., their guns erupted in a furious bombardment ahead of an infantry advance. Many shells overshot Prospect Hill, missing the Confederate cannoneers under orders to hold their fire, but wreaking havoc on men and horses behind them.

Coleman and his reserve artillery awaited orders.

The Union infantry attacked about noon. Prospect Hill erupted in a roar of lead and iron, belching from the fiery mouths of cannon. Below the artillerists, gray infantrymen hit the advancing troops with well-aimed musketry. The unyielding, ferocious fire battered and drove back the Union attackers.

An hour later, another wave of federals advanced. This time, alert Union cannoneers had observed the puffs and drifts of battle smoke from Prospect Hill, and calculated the position of the Confederate cannon. They responded with well-aimed shots that left wounded men, dead horses, disabled guns, and scattered debris from wrecked batteries.

In this precarious moment, the Confederates ordered in a portion of its reserve batteries, which helped repulse the second Union attack. Coleman was not involved, and the inaction gnawed at him. He itched to get his batteries into action.

At some point after the second repulse, Lt. Col. Coleman anticipated another attack and acted on his own initiative to prepare for it. Captain Dance, his comrade from training camp back in 1861, explained the situation to Coleman’s biographer: Coleman “was anxious to render some service and sought out the General commanding that part of the line and obtained leave to place some of his guns in position, and two guns of my battery were all he could find room for.”

The place was at the south end of Prospect Hill, to the left of a pair of Parrott guns belonging to Capt. William T. Poague’s Rockbridge Artillery. Poague, a graduate of Washington College, had met Coleman earlier in the war and become much attached to him. Eight years Coleman’s junior, Poague’s memoirs include a humorous episode that occurred months earlier, after they had joined Jackson’s Corps. He recalled that Coleman joshed with him about the superior drill of other batteries to his. Poague playfully replied that “Old Jack” had kept them too busy for drilling. Coleman “accepted the explanation laughing and said, ‘You are excused, you are excused’—much in the fashion, I fancied, he would have treated a favorite pupil in Greek.”

Armed with orders to bring up Dance’s howitzers, Coleman faced a new challenge—how to get them there. The ground between the guns and the frontline position had been torn up by the enemy’s overshooting its target earlier in the day, and had been made worse by men, horses, and cannon wheels that churned the partly frozen mud into a quagmire. Scattered debris added to the difficulty. Undeterred, Coleman pressed on, offering to help fill up a ditch to bring the guns up.

While Coleman, Dance, and the howitzers powered through muck and mud, another drama played out in Poague’s artillery section after Jackson arrived on the scene. Poague recalled that the general, dressed in a new uniform, pulled out his field glass and pinpointed an enemy battery firing away. Jackson called Poague’s attention to it.

Poague recalled, “I replied in affirmation and that I had for sometime noticed it firing at something away to my right. ‘Can’t you silence that battery?’, he asked. ‘We can try General,’ I said. ‘Well open on it,’ he ordered, ‘and if they get too hard for you, turn your gun on their infantry and try and stampede that!’ He at once turned and went off to the left.”

Colonel Coleman came rushing right into the vortex of the storm demanding: “What does all this mean, Captain! Who ordered you to open fire?” “General Jackson himself” I replied.”

—Capt. William T. Poague

Poague’s Parrotts promptly opened on the battery, which responded. Other enemy guns joined in, sending a perfect storm of shot and shell at Poague’s section.

Dance’s howitzers wheeled into position as the duel unfolded. Poague recalled, “It was not long before Colonel Coleman came rushing right into the vortex of the storm demanding: ‘What does all this mean, Captain! Who ordered you to open fire?’ ‘General Jackson himself’ I replied. ‘Well, I take the responsibility of ordering you to stop,’ he stated. ‘Very well, Colonel,’ I responded, ‘those Yankees down there will pretty soon compel us to quit, anyway.’”

Moments after this exchange, Yankee led tore into and killed Coleman’s bay horse. Then, a bullet hit Coleman in his leg just below his knee. Coleman remained on his feet, for the wound was slight. However, it bled profusely, and, growing faint, he finally left the field—but not before he could judge that the order from Jackson had been countermanded and carried out, and that Poague and Dance were safe.

Coleman received treatment at a field hospital, and joked about a “good furlough.” In relatively good spirits despite the loss of blood, he ministered to seriously wounded soldiers around him. After medical personnel cleared Coleman, he traveled to nearby Caroline County to recuperate at Edge Hill, the home of a brother-in-law. It did not go well. Infection—virulent erysipelas—set in. Thus began a battle for life that lasted almost 100 days. Coleman suffered terribly as the infection spread from his leg and his flesh melted away, leaving him little more than a skeleton. He drifted in and out of consciousness, sometimes crying, other times speaking of family, faith, and war. “Tell Gen. Jackson and Gen. Lee,” he uttered in one of his lucid moments, “that they know how Christian soldiers can fight, and I wish they could see now how a Christian soldier can die.”

At one point as he writhed in excruciating pain, Coleman experienced a crisis of faith. He worried aloud that he might not reunite with God when death arrived. A few days later, he told the doctor attending him, “You remember I said I did not feel God’s presence with me. I could not hear the rustling of the angels pinions. Now I know he is near me, and I feel the breath of the angels wings.”

Coleman lingered until the morning of March 21, 1863. In his final moments, someone in the room said to him, “You will soon be in Heaven; are you willing to go?” He replied, “perfectly willing” and “certainly I am.” These were his last recorded words.

Mary, his beloved wife, sat by his side at the end. He was 36 years old. His remains were buried in the Church of Our Savior Cemetery in Montpelier, Va.

“A life you may copy”

John Lansing Burrows, D.D., a New York native and pastor of the First Baptist Church in Richmond, paid tribute to Coleman’s life and service in The Christian Scholar and Soldier: Memoirs of Lewis Minor Coleman. Published in 1864, Burrows wrote the 32-page pamphlet to motivate young men to follow Coleman’s example. “Such a sketch as this cannot fail to be more useful, in so far as it is practical and useful, in so far as it is practical and imitable. Here are excellencies you may attain, a character you may emulate, a life you may copy.”

The timing of Coleman’s death is noteworthy. The Army of Northern Virginia seemed invincible, and final victory within its grasp under the leadership of Lee, Jackson, Longstreet, and other able commanders. Coleman would never know of the death of Jackson just two months after his own, the twin losses of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and the grueling operations that culminated at Appomattox.

The timing of Coleman’s death is noteworthy. The Army of Northern Virginia seemed invincible, and final victory within its grasp under the leadership of Lee, Jackson, Longstreet, and other able commanders. Coleman would never know of the death of Jackson just two months after his own, the twin losses of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and the grueling operations that culminated at Appomattox.

When the war ended, Coleman’s beloved University of Virginia numbered eight men. Dr. Maupin resurrected the institution on his own credit before he died in an 1871 carriage accident.

One of the finest tributes to Coleman were offered on May 29, 1867—Commencement Day. Colonel Marmaduke Johnson, a one-time subordinate to Coleman in the army and a University of Virginia alumnus, spoke to the graduates, families, friends, and fellow alumni. He addressed Virginia’s glorious past as an agricultural and cultural giant among the states in the early history of the nation, the ruinous war that laid waste to the country and cost so many lives, and the need to rebuild the state’s fortunes in Reconstruction America.

Reflecting on those absent alumni who perished in the war, he eulogized the fallen professor and artillerist from Hanover County: “Lewis Minor Coleman, the brave, the brilliant, the good, who showed in every circle in which he moved, and whose talents and rare attainments gave promise of such usefulness in the future, who at the call of duty left a place of ease and comfort for the hardships and dangers of the army, and fell at Fredericksburg one of the noblest sacrifices on his country’s altar.”

References: Nicholas, Powhatan, Salem and Courtney Henrico Artillery; Burrows, The Christian Scholar and Soldier: Memoirs of Lewis Minor Coleman; Page, Hanover County: Its History and Legends; Du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families; Richmond Dispatch, April 19 and 27, 1861, July 2, 1867; Lewis Minor Coleman military service records, National Archives; Hotchkiss and Waddell, Historical Atlas of Augusta County, Virginia; Cockrell, ed., Gunner with Stonewall: Reminiscences Of William Thomas Poague; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

2 thoughts on “Gifted Scholar, Faithful Christian, Reluctant Soldier: The life and times of Virginia professor and artillerist Lewis Minor Coleman”

Comments are closed.