By Ronald S. Coddington, with images from the Mark Jones Collection

On an April day in 1864, in a field near Alexandria, Va., thousands of soldiers and civilians gathered to witness a military execution. The condemned, Pvt. John H. Thompson of the 1st Ohio Cavalry, had been tried and convicted of desertion and attacking loyal Union men in Northern Virginia, sometimes alone or in league with Col. John Singleton Mosby’s Rangers.

An observer described the scene: “He was shot upon his own coffin, by a squad detailed for the purpose, from the 1st D.C. Regiment. The religious ceremonies were effacing in the extreme. After prayer, by the Chaplain in attendance, a hymn sung, in which the prisoner joined, his voice sounding clear and strong above the others. He evinced the utmost calmness, never moving a muscle in agitation up to the command, ‘Aim. Fire.,’ which consigned him to eternity. He met his death more with the air of a martyr than of a traitor. His conduct and conversation prior to his execution indicated penitence.”

The mournful strains of an army band deepened the solemn gravity of the occasion. The musicians were stationed in the Military District of Alexandria, commanded by Brig. Gen. John Potts Slough. A fiery-tempered Ohio attorney in Colorado Territory when the war began, Slough became colonel of the 1st Colorado Infantry, popularly known as the “Pike’s Peakers.” Historians credit Slough with the strategic victory at the March 1862 Battle of Glorieta Pass, following which Confederate forces abandoned efforts to occupy New Mexico Territory.

Believing his work in the West complete, Slough resigned and headed East. Promoted to brigadier general and assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division of the 2nd Corps in the Army of Virginia, he joined his new command at Harpers Ferry in May 1862.

During this early war period, most Union army regiments had their own brass bands. The 60th New York Infantry, under Slough’s command, was no exception. Organized the previous October in St. Lawrence County, N.Y., as the First St. Lawrence Regiment or the Ogdensburg Regiment, its 20-member band thrived under the leadership of 24-year-old Henry S. Wright.

Regimental bands did not survive the war. In June 1862, Congress debated the elimination of them in favor of fewer brigade-level bands as a cost-saving measure. While legislators in Washington, D.C., discussed the pros and cons, Wright asked his colonel, William Bingham Goodrich, that he and his fellow musicians be discharged.

Their music never sounded half so sweet at any time when we were in permanent camp and barracks as it did at the close of a weary march, at evening parade, or in the Sabbath service, or at the burial of the dead.

—Chaplain Richard Eddy 60th New York Infantry

Goodrich declined. Congress passed the bill in July, and the process of mustering out bands unfolded. The chaplain of the 60th, and author of its regimental history, Richard Eddy, offered candid observations of the band’s members: “During the rest of their stay with us they were very much discontented. Without intending them any injustice, I here record what I several times said to them in person: they complained without just cause; their exposures were no more than fell to the lot of their companions; their duties not as arduous, nor their hardships near so great. Their music never sounded half so sweet at any time when we were in permanent camp and barracks as it did at the close of a weary march, at evening parade, or in the Sabbath service, or at the burial of the dead. They did not fully appreciate its power under such circumstances, but others felt and owed its soothing and ennobling influence. I regret the influence with which they continued with us, but more deeply deplore the mistaken economy of the Government in discharging the Regimental Bands.”

In the end, the musicians remained in service as Slough’s Brigade Band, its 16 members joining the general in the relatively less stressful environs of Alexandria. Leader Wright did not live to enjoy this assignment, as he succumbed to disease on Sept. 5, 1862.

Wright was the second of two bandsmen to die during the war. George Riley Ries preceded him in death from the same affliction.

Less than two weeks after Wright passed, Col. Goodrich suffered a death wound in the Battle of Antietam. Widely mourned by his comrades, his remains were sent to his home in Canton, N.Y., for burial. Had he discharged the band, some of the musicians might have played during his funeral. However, that task fell instead to a local band in Canton.

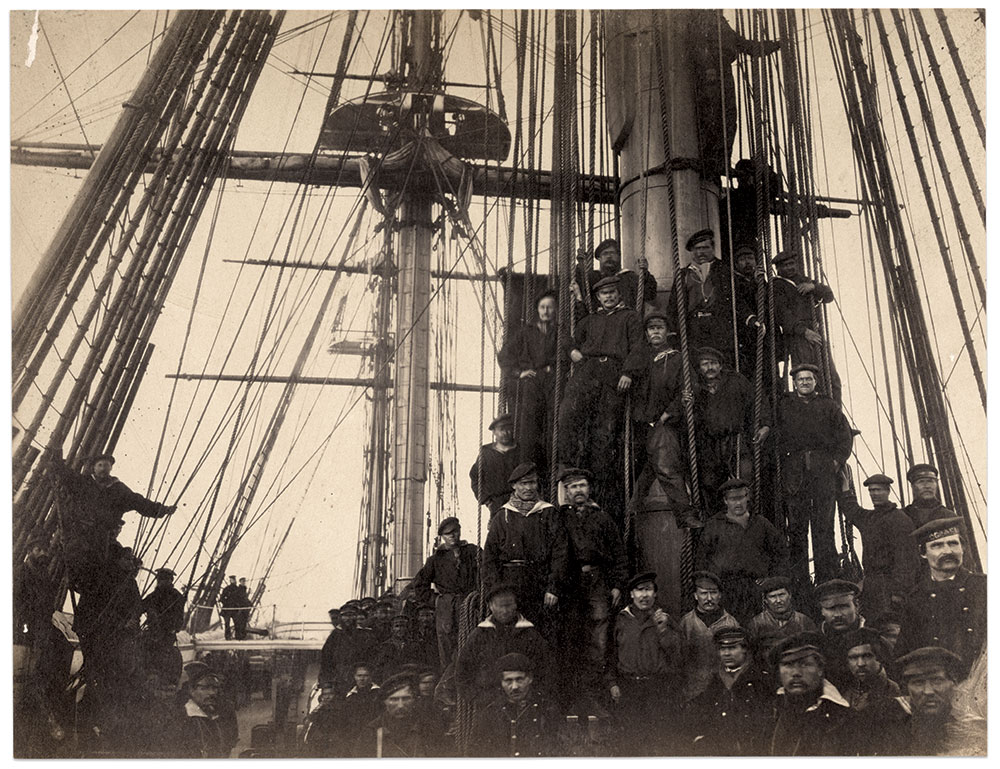

Slough’s Brigade Band thrived in Alexandria. One of its highlights occurred in early December 1863, when a squadron of four warships of Russia’s Baltic Fleet anchored off the city. The visit by the Czar’s Navy was part of a diplomatic mission that began a couple of months earlier in coordination with its Pacific Fleet. The Russians arrived to great fanfare in New York City, Washington, and San Francisco. The visit caused great consternation on the other side of the Atlantic, where a surprised Britain reacted to the savvy move by its geopolitical rival by reconsidering its strained relationship with the United States.

America, the cradle of liberty, the home of the oppressed and downtrodden of every nation under the sun, had been taught what liberty truly was by the great act which liberated millions of Russians from slavery and serfdom.

—Toast to visiting Russians

Soon after the warships arrived in Alexandria, a delegation led by Gov. Francis H. Pierpont of the Restored State of Virginia, Brig. Gen. Slough and his staff, and a party of other military and civilian persons paid its respects to the Russians. On board the flagship Alexander Nevski, the Americans offered toasts to celebrate the relationship between the two countries. One Union officer paid tribute to the Czar’s 1861 decree that emancipated serfs from their feudal lords: “America, the cradle of liberty, the home of the oppressed and downtrodden of every nation under the sun, had been taught what liberty truly was by the great act which liberated millions of Russians from slavery and serfdom.” Slough’s toast was, “Friendship, the great bond of Union between Russia and the United States—may it never be broken.”

A postwar reminiscence by surviving musicians noted that the band accompanied Slough aboard the vessel and performed “The Star-Spangled Banner,” adding, “on one of the first occasions when it was played on Russian territory.”

Slough generously shared the band with area civic groups for special events. On one occasion, the musicians packed up their instruments for an excursion aboard the steamship Fulton to Glymont, a resort on the Maryland side of the Potomac south of Alexandria. The band performed in a pavilion, where dancing and basking in the country air was the order of the day. However, these civilian functions proved so popular and numerous that Slough ended the practice.

The band’s proximity to Washington afforded the musicians an opportunity to witness two monumental events at the close of the war.

On April 21, 1865, they joined crowds who watched the procession escorting the remains of President Lincoln from the Capitol Building, where Brig. Gens. Slough and William Gamble, and their staffs, served as the guard of honor, to a train depot. This solemn event marked the beginning of Lincoln’s final journey by rail through the Union-loyal states to Springfield, Ill., for burial.

The following month, the band attended the Grand Review of the victorious Union armies through the streets of the capital city.

Slough’s Brigade Band members received their discharges in Washington on June 24, 1865. The musicians melted back into society and scattered across the country.

Almost a half-century after the war, in 1913, five surviving members of the band gathered for a reunion dinner in Minneapolis, Minn. A news report of the event and a sketch of the band’s history in Alexandria provided the foundation for this narrative.

Special thanks to Mark Jones for sharing his images and research. He was assisted by John Bieniarz, Ralph Dudgeon, Mark Elrod, The Lawrence County Historical Society, the Potsdam Public Museum, and Sara Day Schultz and Carrie Rutherford of the Madrid, N.Y., Historical Society.

References: Litchfield Inquirer, Litchfield, Conn., May 19, 1864; Eddy, History of the Sixtieth Regiment New York Volunteers; Alexandria During the Civil War: First Person Accounts, alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/first-person-accounts; The Minneapolis Journal, Oct. 16, 1913; Naval Historical Foundation, The Russian Navy Visits the United States; The New York Herald, April 22, 1865.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.