By Sidney Dreese

Nothing mattered more to Sarah “Sallie” Chamberlin than to live a useful life. A fire burned in her patriotic heart, and she was both anxious and determined to become a nurse after the war began. The noble work embraced by women during the crisis was not for her: rolling bandages, making jams, apple butter, and condensed soups, sewing cotton shirts, crafting cushions for wounded limbs, and doing anything else to comfort sick and injured soldiers.

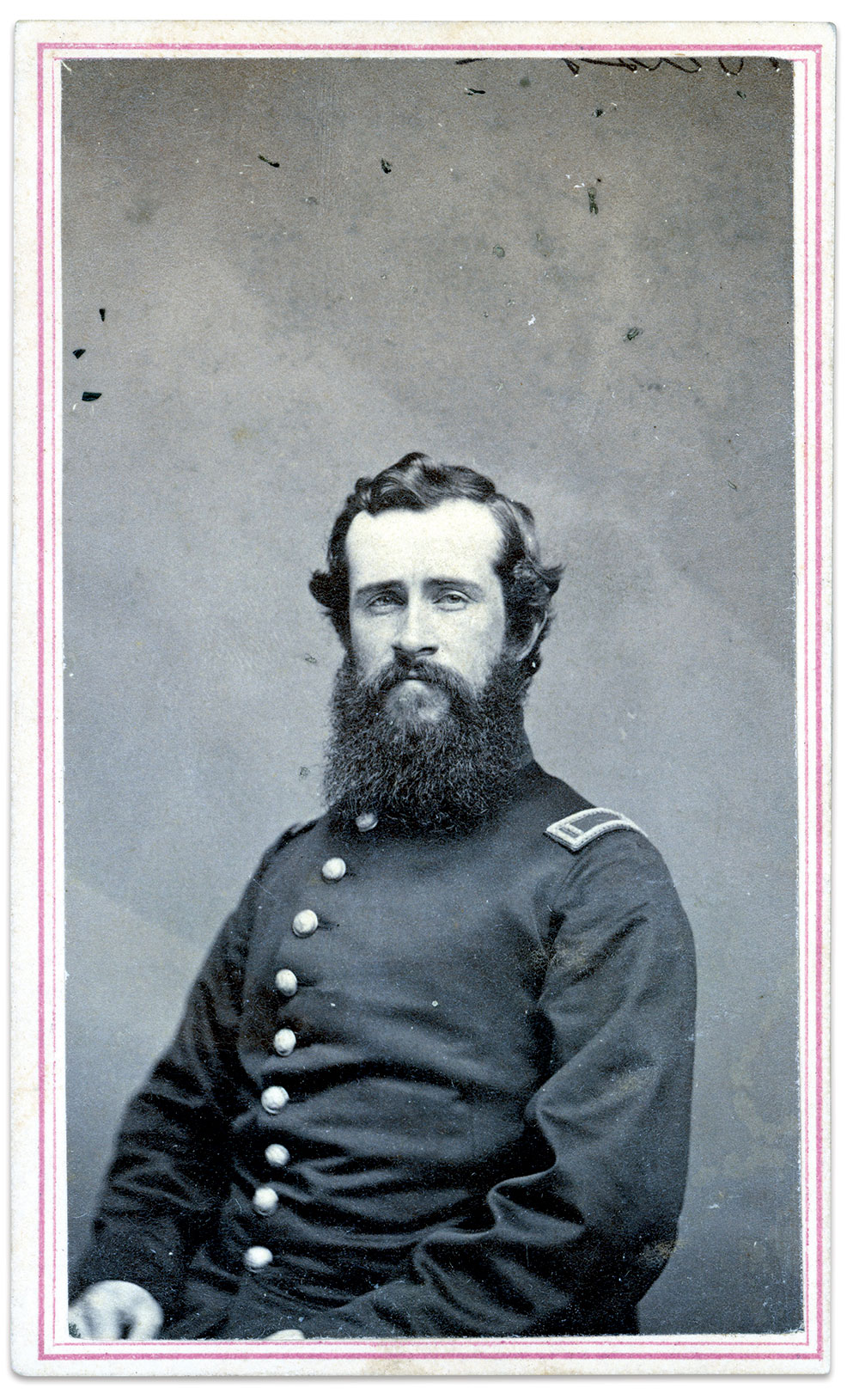

Sallie drew inspiration to become a caregiver from her family and friends. Several of her brothers served in the military, notably Thomas, two years Sallie’s senior. As an officer in the 34th and 150th Pennsylvania infantries, he suffered a wound and fell into enemy hands during the Peninsula Campaign, and a second wounding at the Battle of Gettysburg. Two friends, Annie Bell and Sarah Dysart, who Sallie had met while attending the Female Institute of the University at Lewisburg (Bucknell University) became nurses.

A formidable obstacle blocked Sallie’s path to nursing in the U.S. Army. Dorothea Dix, the stern and inflexible Superintendent of Army Nurses headquartered in Washington, D.C., had established acting standards for incoming nurses. Dix insisted they be between 35 and 50 years old, in good health, practiced good hygiene, possessed high moral standards, were plain looking, and dressed modestly. Sallie’s age, 21 when the war started, instantly disqualified her.

Sallie navigated this roadblock with the help of a family friend, George Cadwalader, a respected major general who had served in the Mexican War. He helped her obtain a military pass and bypass Dix.

I saw so much to be done that I am anxious to be at work.

On Jan. 22, 1864, Sallie boarded a train in Philadelphia headed to the Western Theater. Eight days later she arrived at a train depot in Nashville and reunited with her college friends, Annie and Sarah, nurses at a Nashville military hospital.

Sallie’s first diary entry after her arrival underscores her desire to help. On January 31 she wrote, “I saw so much to be done that I am anxious to be at work.”

Sallie soon learned how busy the hospital could get after 115 patients arrived. She busied herself making the patients as comfortable as possible, and wrote in her diary, “I am beginning to grow fond of my work.” Long, grueling days left her fatigued in the evenings.

The tasks she performed varied. On one occasion, Chaplain John Poucher of the 38th Ohio Infantry asked her to help deliver thermal underclothes to patients being sent North in the winter cold. On another day, she was asked to distribute crutches.

The death of patients in her care caused great anguish and emotional distress. Comments in her diary include:

“Poor Boys! How hard to see them die so far from home & loved ones.”

“It is discouraging to have so many die.”

“We think of the friends who are left to mourn.”

“How many noble hearts must cease to beat before this strife is ended?”

The presence of teenagers surprised Sallie. One soldier, she noted, was “a mere boy only fifteen years of age.” Another, 19-year old John Q. Hornbeck of the 4th Ohio Cavalry, died of measles and left behind a wife and child to mourn his loss. She described another young man, Thaddeus Sage Tillotson of the 15th U.S. Infantry, as “a sweet little fellow.” He succumbed to inflammation of the brain.

Sallie also celebrated survivors. One Michigan soldier she recorded as Robert Settell had his right arm amputated. She “was afraid he could not bear it, but he bore it remarkably well. Another patient with the last name Peterson trusted Sallie with caring for his money. After medical personnel transferred him to Louisville, Ky., to continue his recovery, she sent the money to him by express. He sent her a letter of gratitude.Perhaps the most surprising encounters Sallie had involved soldier girls.

Sallie described one patient in her diary for March 5, 1864: “This afternoon quite an excitement was raised by the arrival at our hospital of an ambulance containing a soldier girl who was taken prisoner at Chickamony. Fanny the soldier girl was transported from Nashville to a Chattanooga hospital. Sarah was sent to Chattanooga to take care of Fanny for a few days. Fanny’s wound had to be burned more than once, “and she cried bitterly.” Sallie thought it strange taking care of one patient, as she was typically responsible for many more patients.

A few weeks later, Sallie wrote, “we had an arrival of another soldier girl calling herself Annie Miller” who was in the 101st Ohio, Company C. She called herself George Smith. Sallie noted, “We do not believe her stories but must keep her overnight.” Military service records include a Corp. George L. Smith of Company G of the 101st, who succumbed to disease at Nashville in December 1862, about a year before Sallie became a nurse.

In time, hospital administrators assigned her to cover three wards. She never shirked her increased responsibility, boasting, “I feel I have not neglected a single duty.” At times though, she would become ill from fatigue and spend an entire day in bed.

Other caregivers suffered. One of them, Dr. Joseph Addison Freeman, who had started the war with the 13th New Jersey Infantry, succumbed to pneumonia. He had befriended Sallie and nurse Annie Bell. The three of them took walks and rides around Nashville, went to church services, and sang and played piano, organ and violin. Sallie recorded in her diary on Dec, 29, 1864, “Our respected dear friend Dr. Freeman died tonight. It seems it cannot be. Our loss is so fresh in our minds that we cannot cease our weeping.” The two women packed his things to return to his family.

In January 1865, Sallie resigned her position. Upon leaving Nashville, she received an gold watch and chain inscribed by her “many friends at General hospitals No. 8 & 1.” Sallie confided in her diary that she felt very unworthy to be so honored.

Sallie went to be a housekeeper for older brother John Wesley “Wes” Chamberlin, a merchant in Norfolk, Va.. Prior to the war, he resided at Lewisburg. After hostilities began, he served in the 4th Pennsylvania Infantry.

At the war’s end, Sallie returned to Lewisburg where, in 1866, she married veteran Charles Frederick Eccleston. He had served as a first sergeant in the 3rd Delaware Infantry and a first lieutenant in the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery.

They started a family that grew to include two children, John and Emily. Sadly, Charles would not see his children grow to maturity as he died in 1875 at age 37.

Widowed Sallie continued to live a useful life. She joined the National Association of Army Nurses of the Civil War. She left for Minnesota and the Winona Normal School, where she taught kindergarten, a German import established in America in 1856. Sallie’s success led to an offer to teach kindergarten in Argentina. With the same dedication and commitment she brought to nursing, she became a noted educator and trainer who established several schools in the South American country. Sallie passed away in 1916 at age 79 in Buenos Aires. Her remains were buried in the city’s Cementerio de la Chacarita. She is celebrated as the grandmother of the Argentine kindergarten movement.

References: Sarah Eccleston Diary and Journal, 1864 and 1865; Luiggi, Sixty-Five Valiants; Crespo and Walsh; Las Maestras de Sarmiento.

A resident of Central Pennsylvania, Sidney Dreese has had an interest in the Civil War since childhood. He and his wife, in their spare time, enjoy visiting Civil War sites. He holds an MA in American Studies from the Pennsylvania State University.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.