By Melissa A. Winn

Capturing the story of Clara Barton in brief is an impossible feat. While many men and women who participated in the Civil War have remarkable narratives, whether it be of heroism, duty, compassion, or citizenship, Clara’s feels like the story of many lifetimes. Her 90 years on Earth barely contained her indefatigable, resolute, and relentless spirit—too vast for this world.

Born on Christmas Day 1821, Clarissa Harlowe Barton was every bit her father’s daughter. Captain Stephen Barton marched from his home in Oxford, Mass., to Detroit, Mich., and enlisted for three years under Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne during the Northwest Indian Wars of 1785-1795. Captain Barton captivated his youngest child, Clara, with lessons on geography, military strategy, and the critical importance of properly supplying an army with weapons, provisions, clothing, and medical care. He and Clara’s mother, Sarah, also made sure that Clara was educated.

She excelled at school and became a teacher at age 17. In 1852, she moved to Bordentown, N.J., where they lacked free public schools. With the help of a local school committee, she opened her own school. It soon grew to more than 200 students, largely based on her reputation and work. The town raised $4,000 to construct a larger schoolhouse. When it opened a year later, Clara was devastated to find out she would not be its principal because the school board felt the job unfitting for a woman. They hired a male to do the job instead, demoting Clara to an assistant. She resigned.

Clara fell into deep depression, which she suffered when she lacked purpose and had idle time on her hands. She was at her best when in service to others.

She found a new sense of purpose by 1854, when she moved to Washington, D.C., and accepted a job as a clerk at the U.S. Patent Office—a notable position (and salary) for a woman of the time.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Clara lived alone in a boarding house on 7th Street. Here she participated in her first service as a nurse to soldiers when injured members of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry arrived in the city after being attacked by pro-secessionist rioters as they passed through Baltimore. Clara treated dozens of them, and collected food, medicine, clothing, and other supplies to distribute to soldiers. Working by herself, Clara created a network of suppliers, mostly women and women’s groups in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere.

In 1862, Clara received permission from Col. Daniel H. Rucker of the Quartermaster Corps to deliver supplies to the front lines. She did, but not without challenges. Clara could not go to the field without a male escort, it being considered an improper place for a woman. Even when following protocol, she faced criticism and complaints from officers such as Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, who felt the battlefield was no place for her.

Ironically, some women questioned Clara’s presence and utility on the front line. They included Superintendent of Army Nurses Dorothea Dix, who challenged other women’s relief organizations and volunteer operations.

Clara struggled to preserve her independence as a one-person operation alongside much larger operations, including the Sanitary Commission, with which she could not compete in volume and reach. However, many found Clara’s presence, supplies, hard work, and support invaluable. Union Army Surg. James Dunn wrote his wife about her work delivering supplies and tending to the wounded of the Battle of Antietam as valiant. Clara, he said, “is the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield.”

In 1864, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler appointed her as the “lady in charge” of the frontline hospitals in the Army of the James. About this time, she received letters from women across the North, addressing her as “the soldier’s friend,” asking for help to search for missing husbands and sons who may have languished or died in southern prisons.

In early 1865, Clara returned to Washington to nurse her brother Stephen and nephew Irving Vassall, who had both fallen ill. Irving, a government employee, told Barton that exchanged Union prisoners were returning in poor condition and the government needed help notifying the relatives of those who were missing or had died in captivity.

Clara wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in February 1865, requesting permission to become a government correspondent seeking those who had vanished during the conflict. To stand out amid the flood of letters he received, she penned hers in ornate and lavish script.

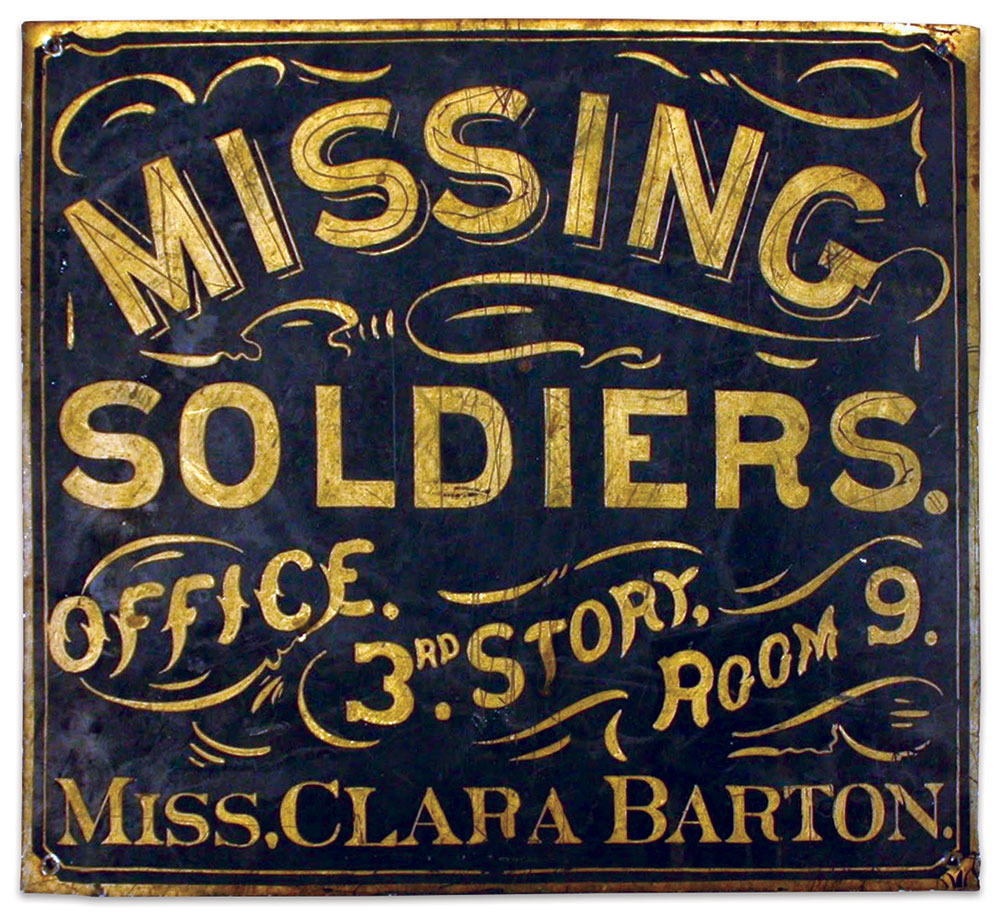

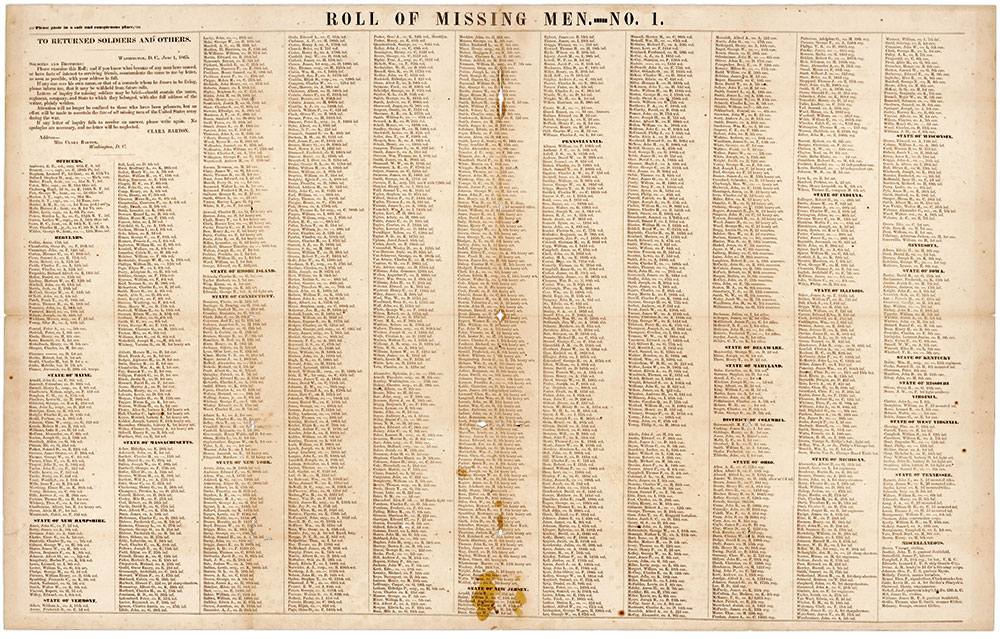

Lincoln responded. On March 24, 1865, he sanctioned her work. Clara established The Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army in her 7th Street boarding house. Clara led a team of nearly 20 clerks at the Missing Soldiers Office, where they compiled a master list of soldiers who had disappeared during the Civil War. In June 1865, she published the first “Roll of Missing Men” with 1,533 names. By the conclusion of her work in 1868, five separate rolls containing 6,650 names had been published.

Clara learned about the Red Cross during a trip to Geneva, Switzerland, in 1869. This led to the next and one of the highest-profile endeavors of her prodigious life. In 1881, she founded the American Red Cross and served as its president for 23 years, until 1904. She died of pneumonia on April 12, 1912, 51 years to the day the first shot was fired on Fort Sumter, igniting the war that transformed Clara into one of the nation’s most recognizable and compassionate caregivers—and a national icon.

“This war not only opens coffers which have never opened before, but hearts as well,” Clara said. “Dark shadows lie upon the hearthstones, but if in contrast the fading embers of humanity and brotherly love glow with a new radiance, it shall not at last have been in vain.”

Melissa A. Winn has been enchanted with photography since childhood. Her career as a photographer and writer includes numerous publications, among them Civil War Times, America’s Civil War, and American History magazines. She is currently Director of Marketing and Communications for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Melissa collects Civil War photos and ephemera, with an emphasis on Dead Letter Office images and Gen. John A. Rawlins, chief of staff to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Melissa is a MI Senior Editor. Contact her at melissaannwinn@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.