By John Walsh, featuring images from the author’s collection

The triumph by U.S. forces at Fort Donelson in early February 1862 dramatically turned the tide of the Civil War, then in its first year. Newspapers across the Union hailed the victory as breaking the back of the secession serpent. The Southern press noted the shameful surrender precipitated by the unmitigated disaster that befell Confederate arms.

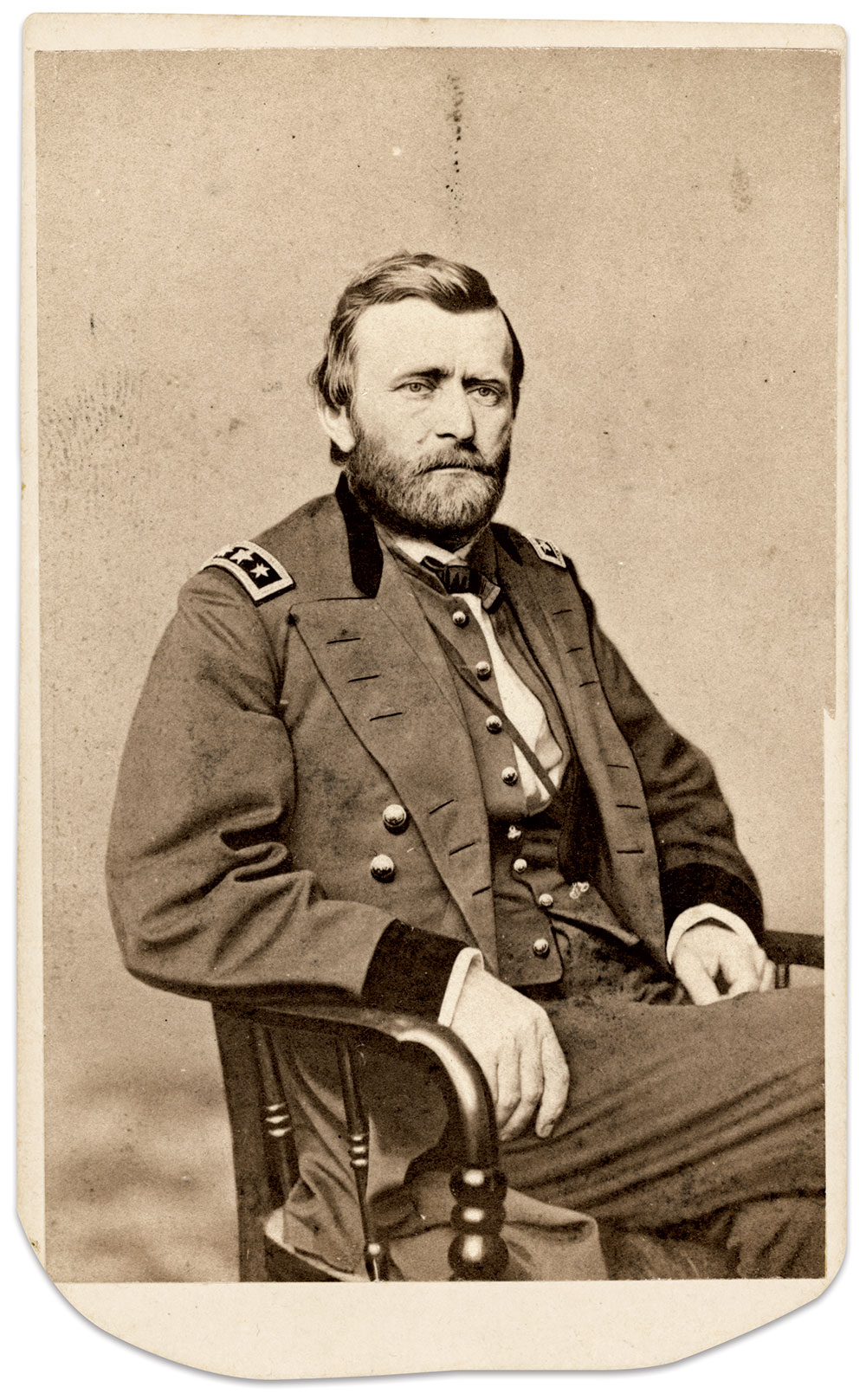

The surrender of 14,600 prisoners, questionable generalship, loss of control of major waterways, and subsequent fall of the Tennessee capital of Nashville cast a pall over the Confederate States. Meanwhile in the United States, the Western army and Brown Water Navy exploited strategic advantages as the country celebrated a newly minted hero who offered one option to his foes—unconditional surrender: Ulysses S. Grant.

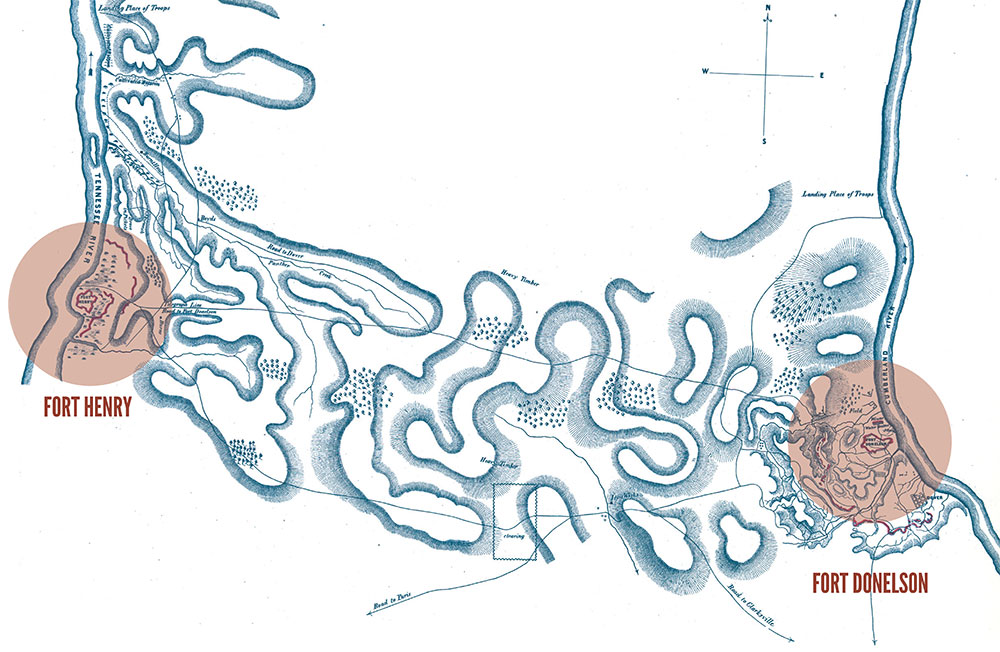

On February 6, Grant, with the support of naval forces led by Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, compelled the garrison at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River to surrender. Grant then marched his troops a dozen miles overland to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River.

The drama at Donelson unfolded over the better part of a week, from February 12-16, and involved more than 40,000 men in blue and gray, plus ironclad gunboats.

Here’s the story of the battle as told through portraits and accounts of representative participants.

Before the Battle: Key Forts

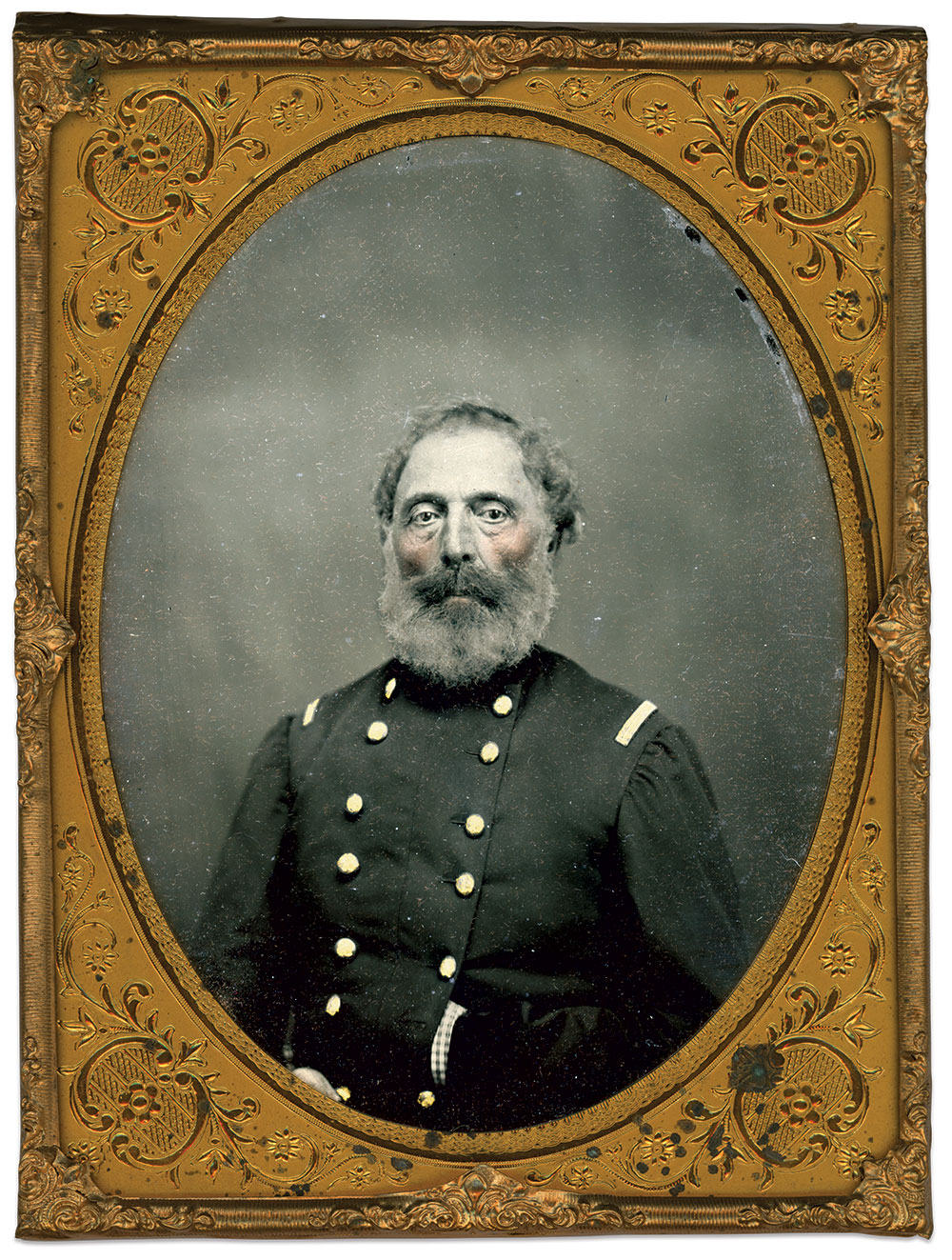

Ironically, Brig. Gen. Daniel Smith Donelson (1801-1863) did not participate in the Battle of Fort Donelson, He did, however, play a role in setting the stage for the fight. Tennessee Gov. Isham Harris directed Donelson to select locations for new forts on the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers. The place he selected along the Cumberland, just outside of Dover and a dozen miles south of the Kentucky state line, was named for him. A garrison of troops and heavy guns occupied the new fort by November 1861. He did not live to see the end of the war, dying from chronic diarrhea at age 61.

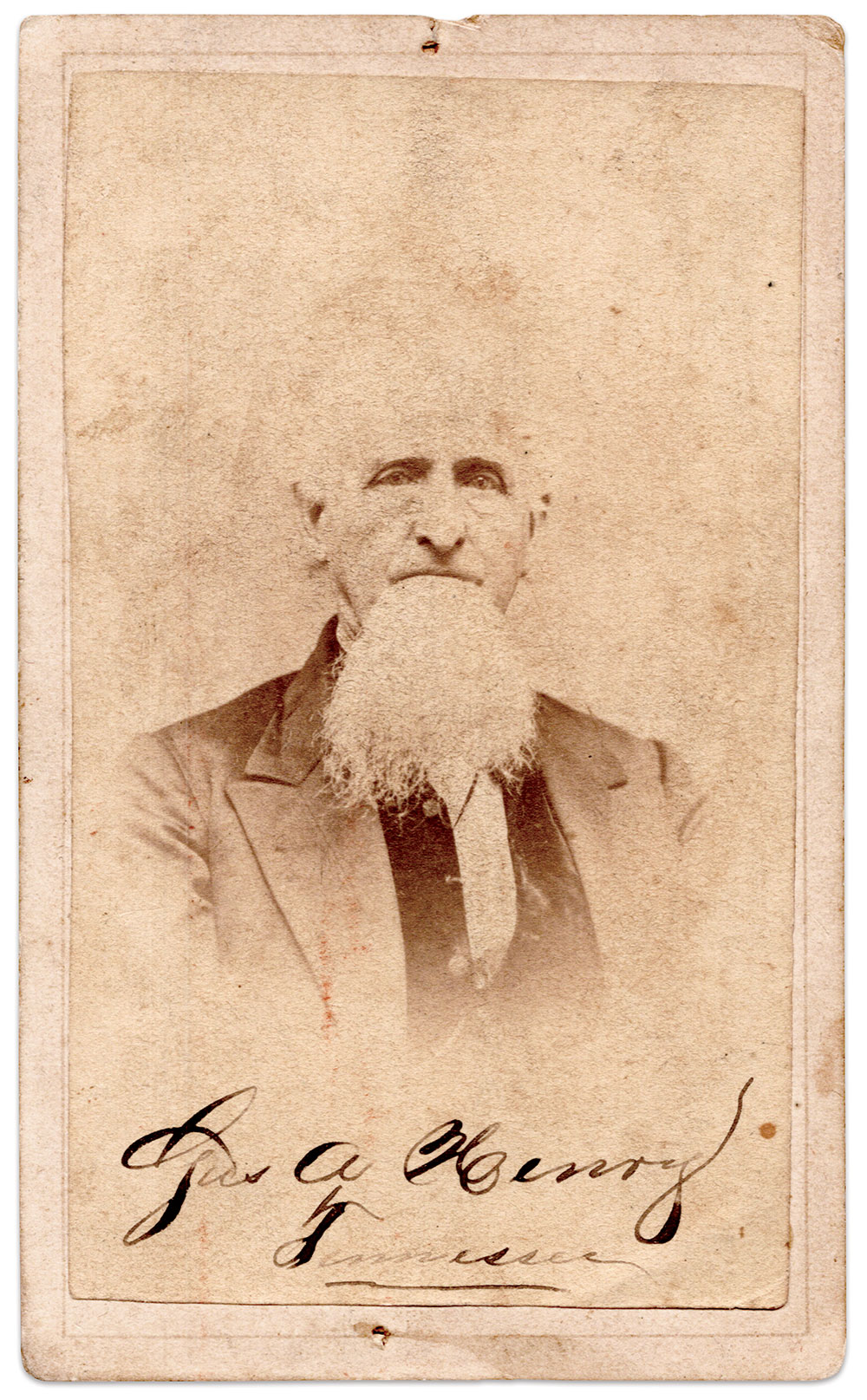

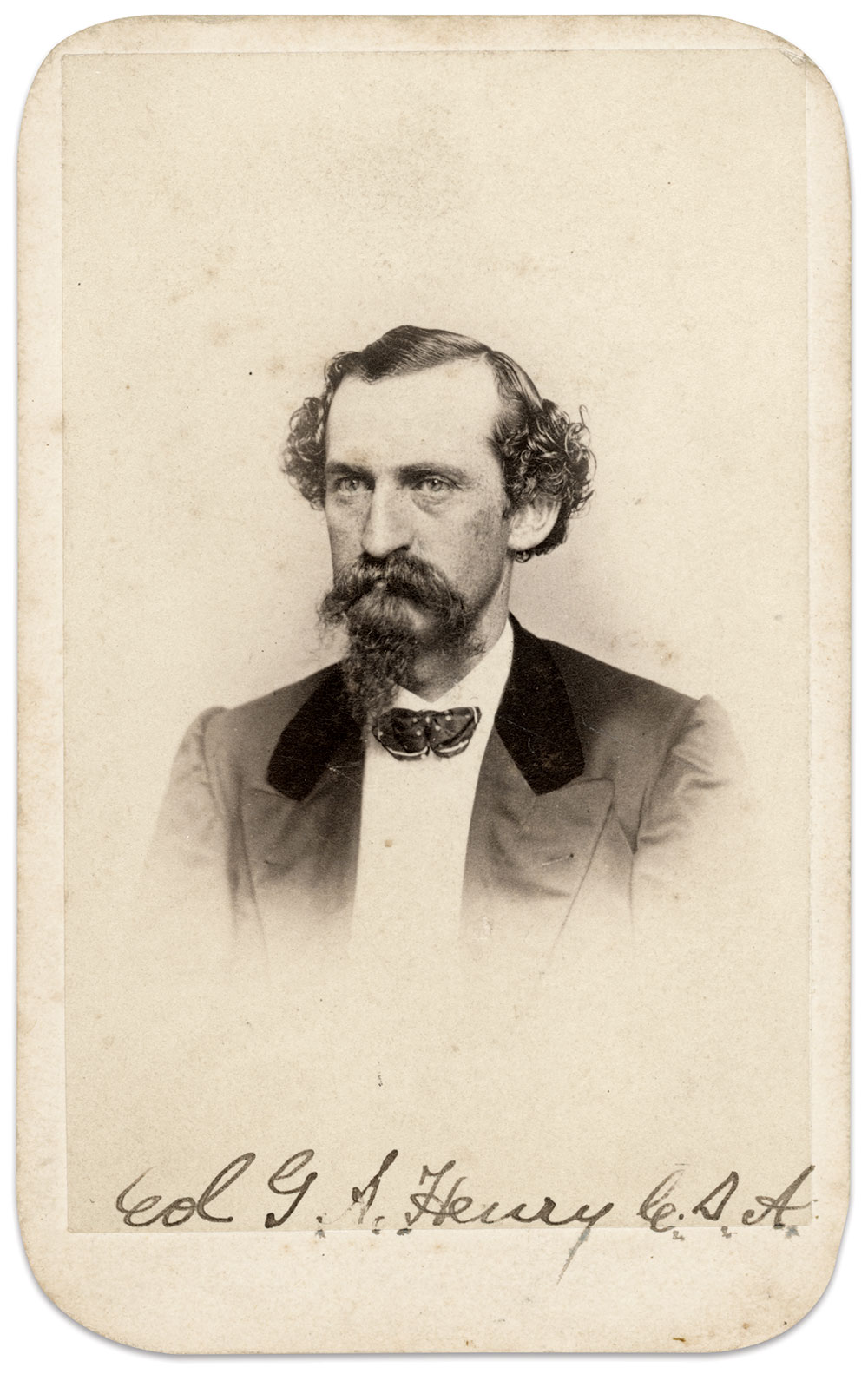

Gustavus Adolphus Henry Sr. (1804-1880), the “Eagle Orator of Tennessee,” received the honor of having the Tennessee River fort named for him. An attorney, he had attended law school with Jefferson Davis, with whom he remained friends. An influential Senator, he served on the finance and military committees of the Confederate government. Fort Henry was selected against the advice of engineers concerned about flooding. But its position, which allowed for an unopposed view down river, won over critics.

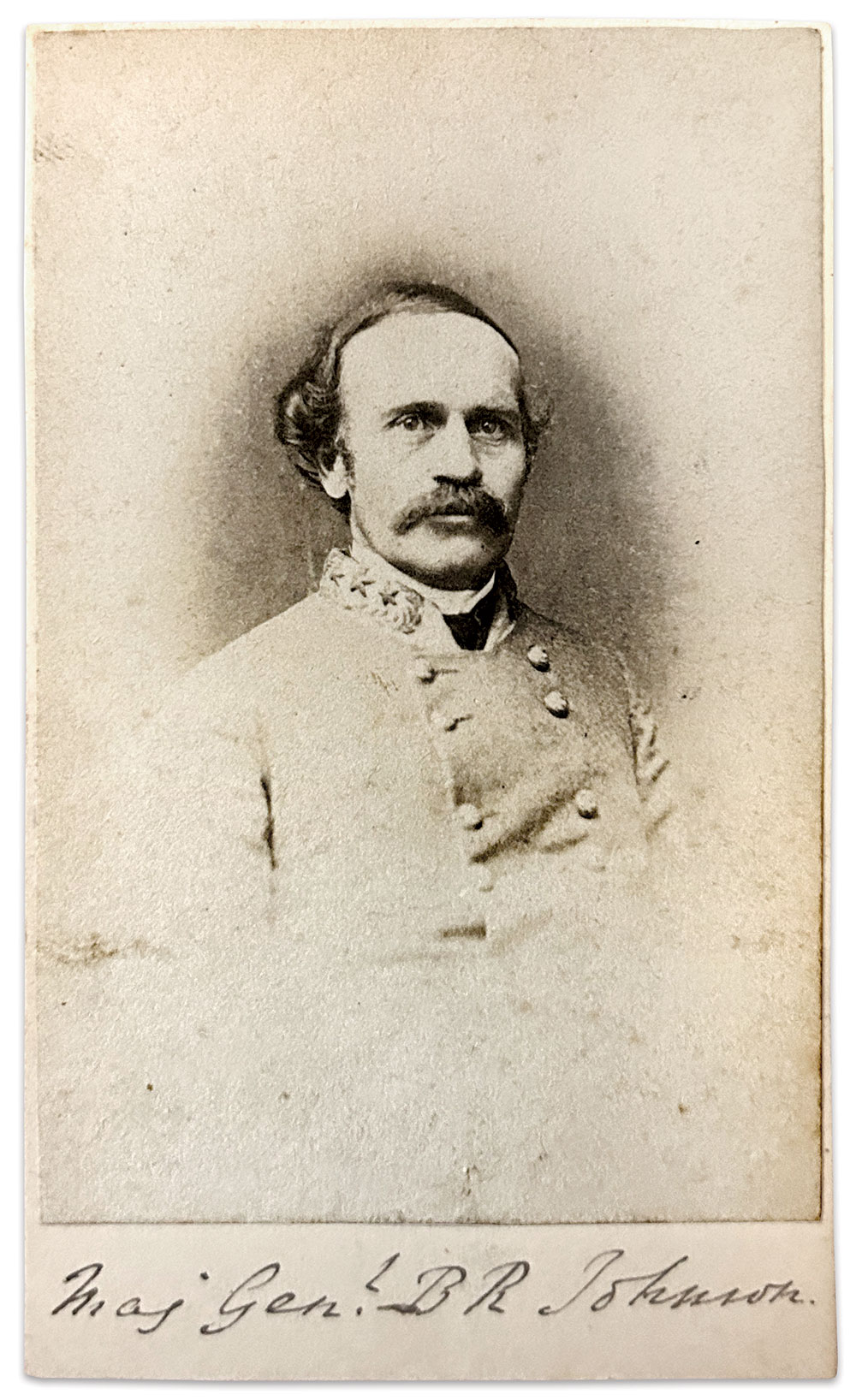

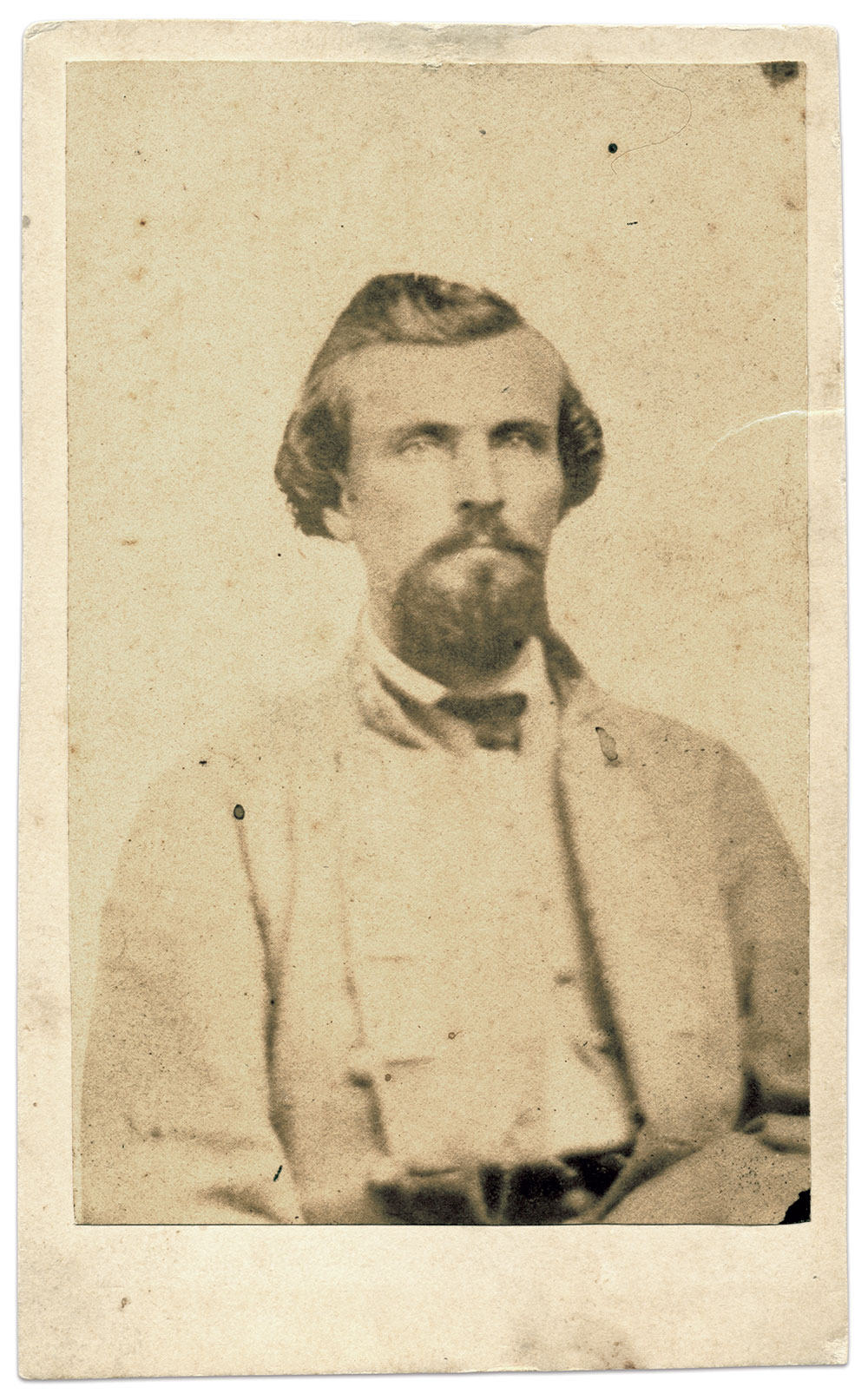

Bushrod Rust Johnson (1817-1880) led the Tennessee Corps of Engineers during the selection of forts. Called to settle a dispute between his engineers and Donelson about the location of Fort Henry at low-lying Kirkman’s Old Landing, Johnson sided with the general. Johnson commanded forces at Donelson for about five hours before Brig. Gen. Pillow arrived, assumed command, and reduced Johnson to a wing commander. He avoided capture and went on to command on the division level in the Army of Northern Virginia.

February 12: Grant Marches on Fort Donelson

Six days after the successful attack on Fort Henry, Brig. Gen. Grant reorganized his army. At approximately 8:00 am on February 12, he and his two divisions, commanded by brigadier generals Charles F. Smith and John A. McClernand, began the 12-mile march east with the objective to envelop and capture Fort Donelson. By 11:00 a.m., the columns arrived within just a few miles of Donelson. Here, the federals met Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest for the first time, skirmishing until about 3:00 p.m., when the Confederates received orders to fall back into the outer works that surrounded the town of Dover and Donelson.

Light skirmishing and sporadic artillery fire occurred during the afternoon as generals Smith and McClernand positioned their divisions. Casualties included George H. Snodgrass, a private in Company H of the 50th Illinois Infantry. A farmer in Brown County, Ill., he suffered a severe thigh wound. Transported to Mound City, Ill., he succumbed to his injury on March 8 at about age 22.

February 13: Action at Redan No. 2

Grant issued orders not to bring on a general engagement until he had positioned his army. He planned to deploy his two divisions on high ridges opposite of the Confederate outer works protecting Fort Donelson, the town of Dover, and the landing by which Confederate troops and supplies arrived. As Brig. Gen. McClernand moved his division into position, his troops came under fire by Capt. Frank Maney’s Tennessee Battery at Redan No. 2. An artillery duel ensued with three Illinois batteries commanded by captains Edward McCallister, Ezra Taylor, and Jasper M. Dresser. Under cover of his batteries, McClernand attacked Redan No. 2 to silence Maney’s artillerists and penetrate what he saw as a weak part of the Confederate defenses. The assault, also known as Morrison’s Attack, failed, resulting in about 200 casualties. Some of the Union wounded became trapped in the burning underbrush resulting from the attack.

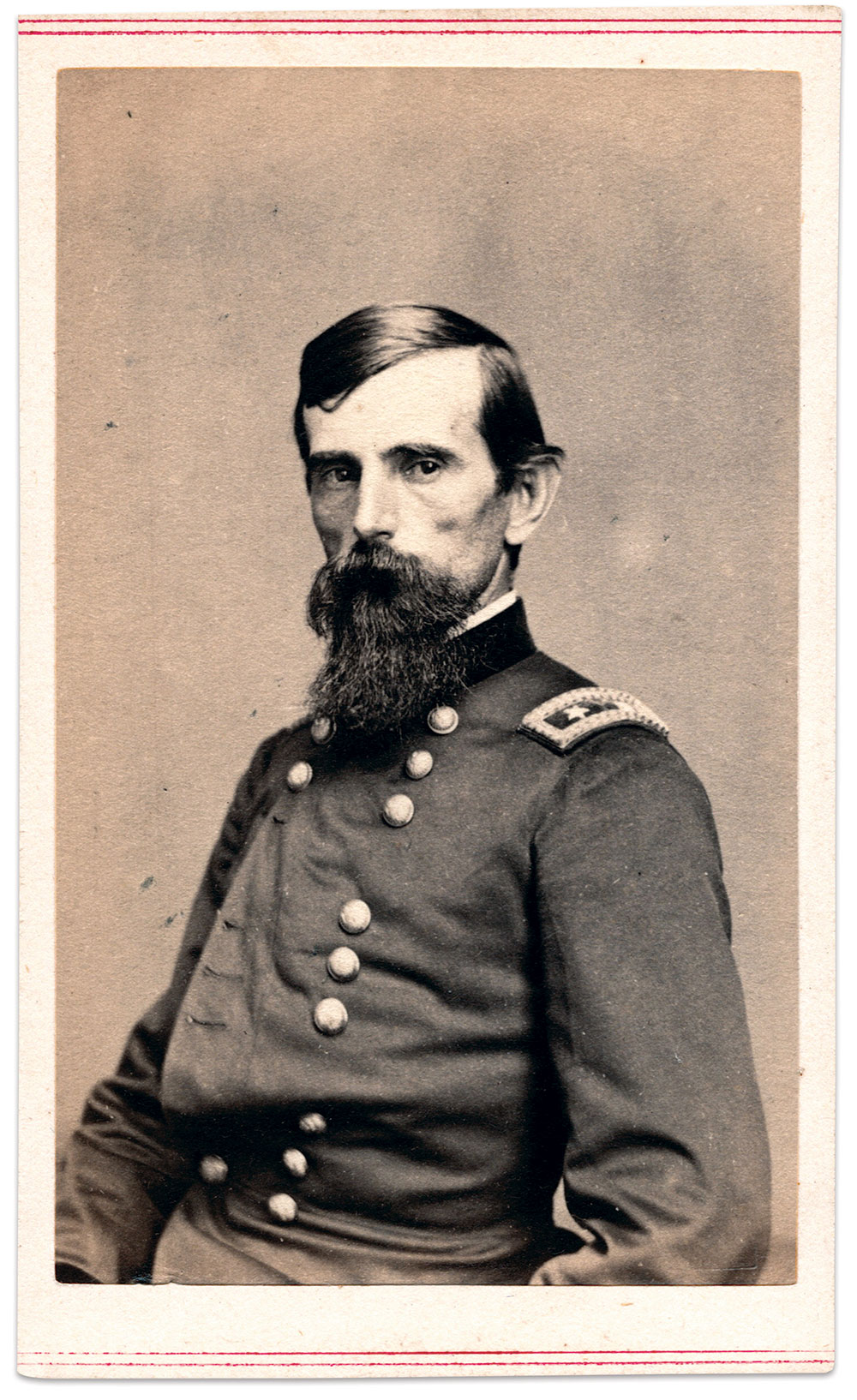

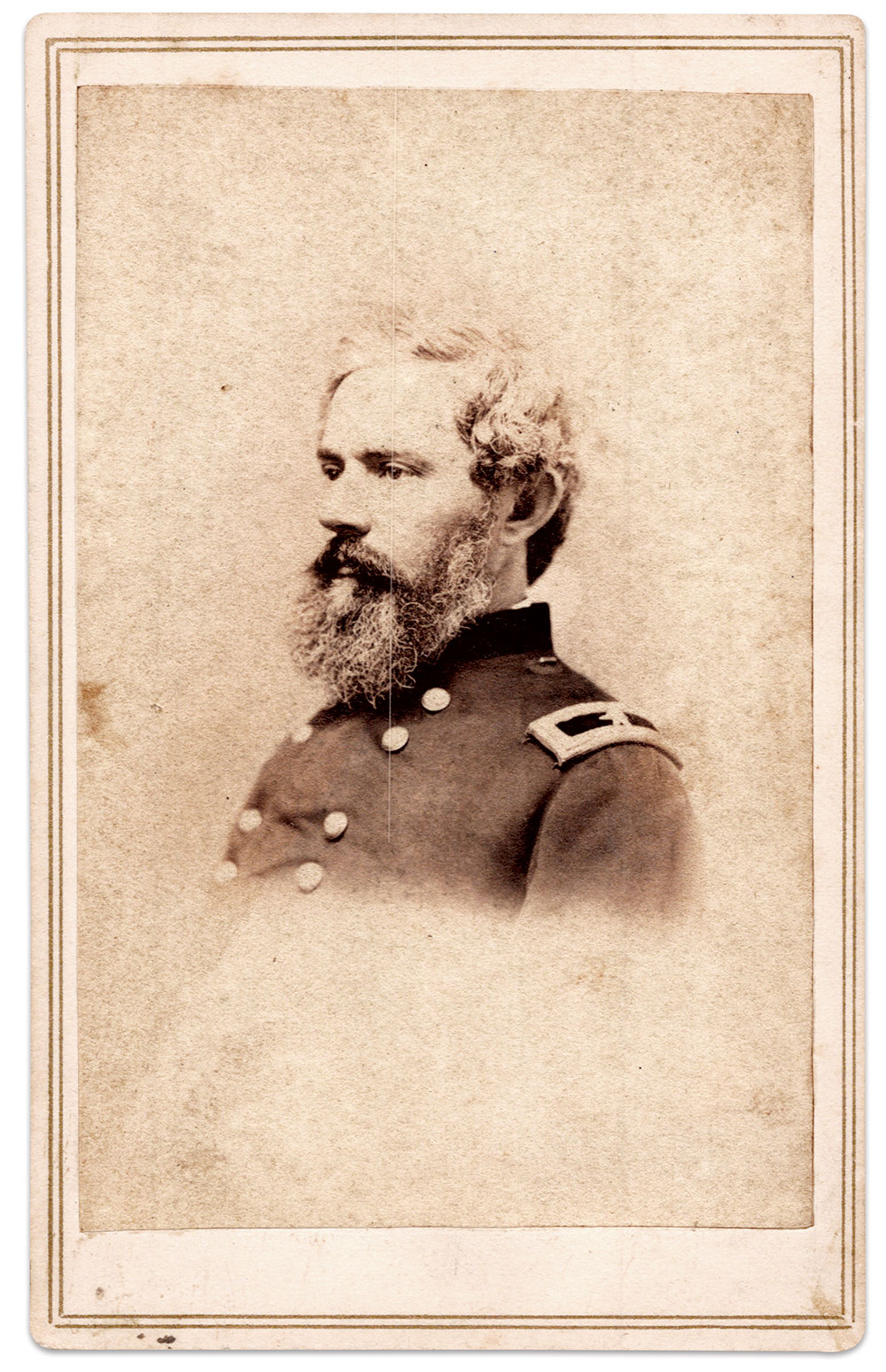

The after-action report of the Second Brigade, First Division, of Grant’s army heaped praise on Ezra Taylor (1819-1885) of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery: “The conduct of Captain Ezra Taylor, commanding Light Battery B, during the whole series of engagements was such as to distinguish him as a daring, yet cool and sagacious officer. Pushing his guns into positions that were swept by the enemy’s shot, he in person directed the posting of his sections, and in many instances himself sighted the guns. Such conduct found its natural reflection in the perfect order and bravery that characterized his entire command. His battery of six pieces fired 1,700 rounds of fixed ammunition during the engagement, being an average of about 284 rounds to the gun.” Taylor received a promotion to major after Donelson, and went on to serve as colonel and Chief of Artillery of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 15th Army Corps.

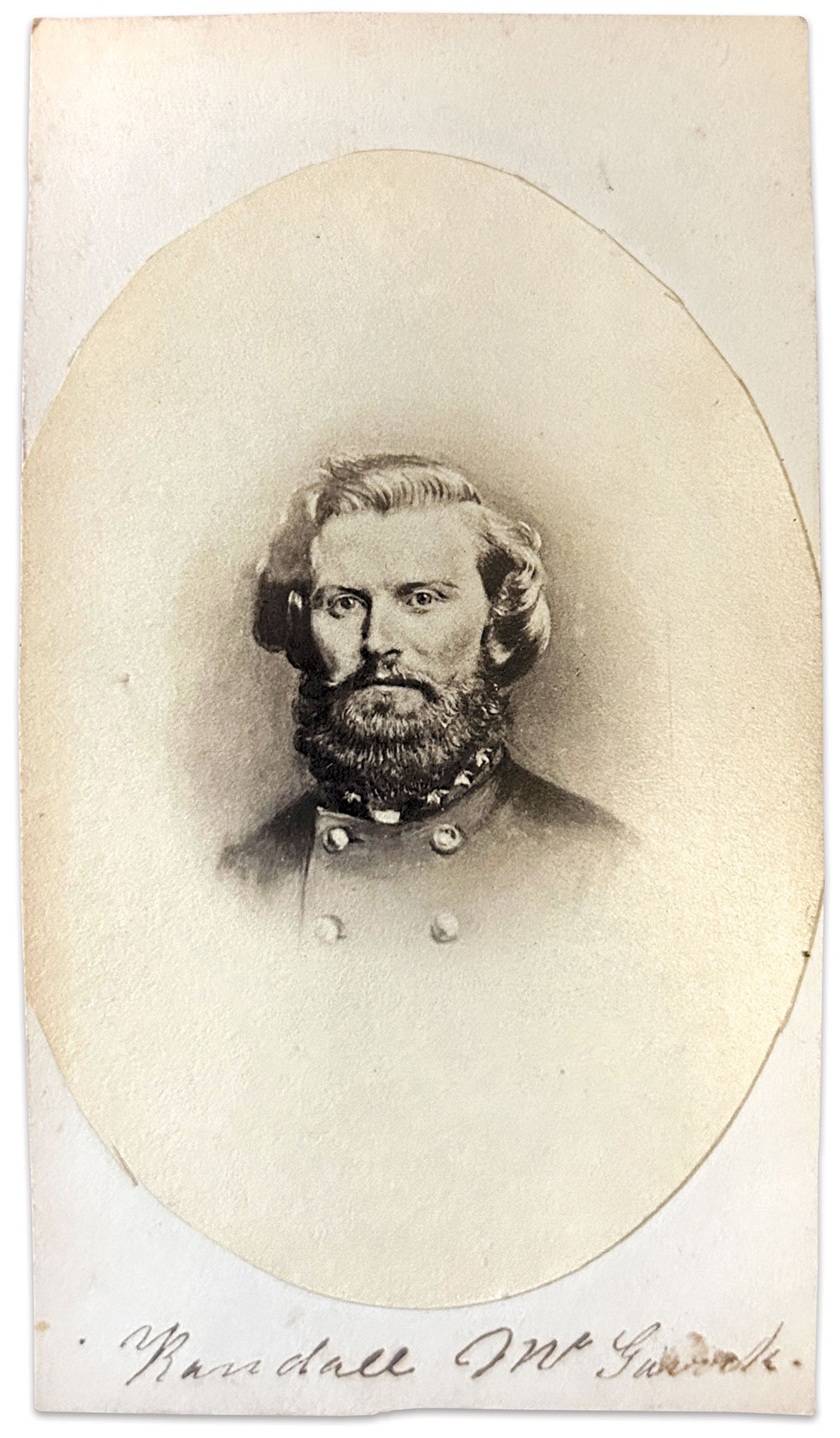

The 10th Tennessee Infantry, manning the entrenchments in front of Redan No. 2, took the brunt of the federal attack. Known as the “Sons of Erin,” the regiment and others repulsed the enemy. The 10th’s colonel, Randal William McGavock, 34, a wealthy former Nashville mayor, raised and outfitted the 10th. The original lieutenant colonel, he advanced to colonel when Adolphus Heiman became a brigade commander. In May 1863, a died at the Battle of Raymond, Miss. He was 36.

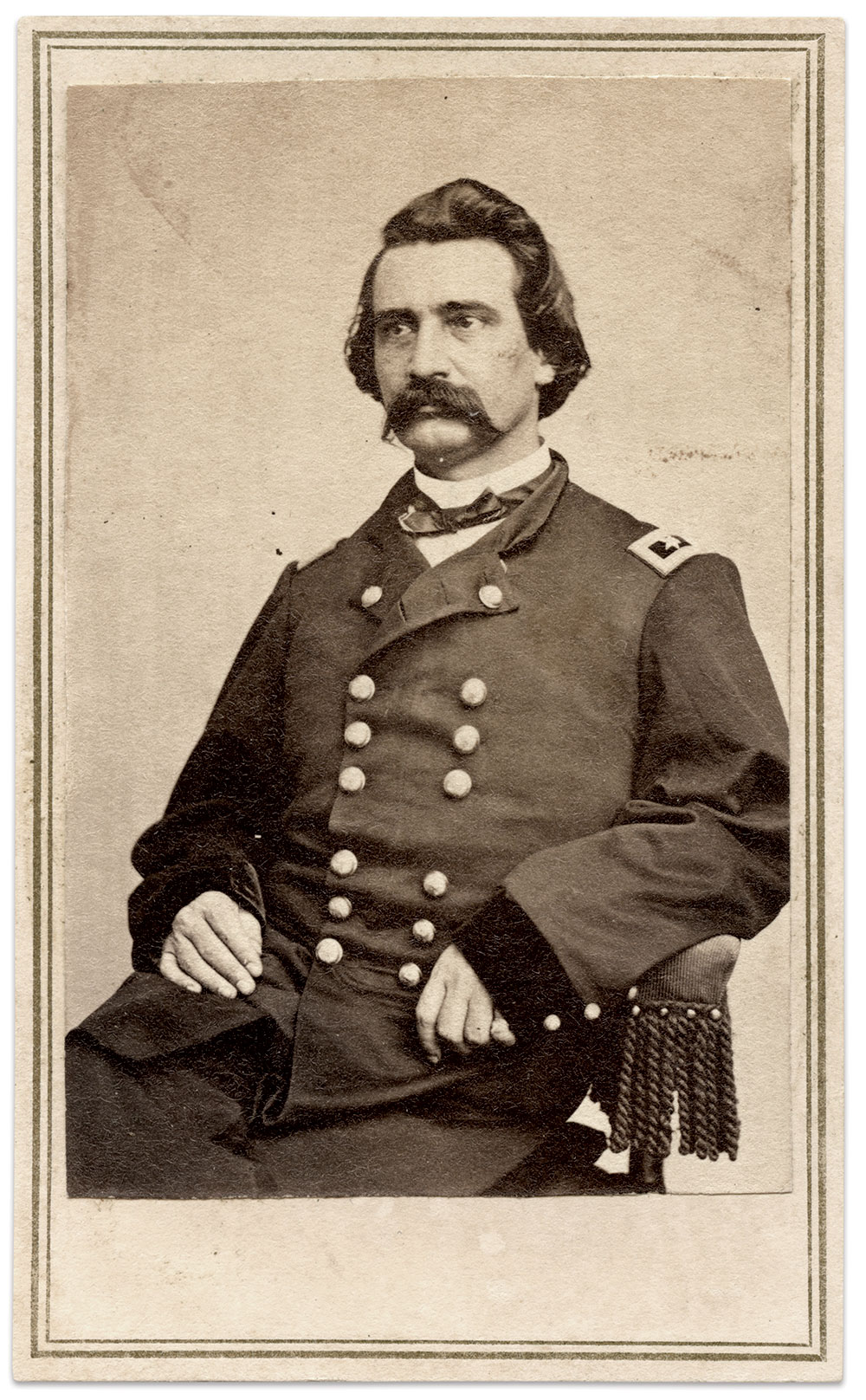

John Alexander McClernand (1812-1900) practiced law and served Illinois as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives prior to becoming a brigadier general in 1861. Though his performance at Donelson was questionable, he advanced to major general. His friendship with President Lincoln and Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, and his creative writing skills, likely contributed to his elevation. McClernand left the army in 1864 due in large part to friction with Grant.

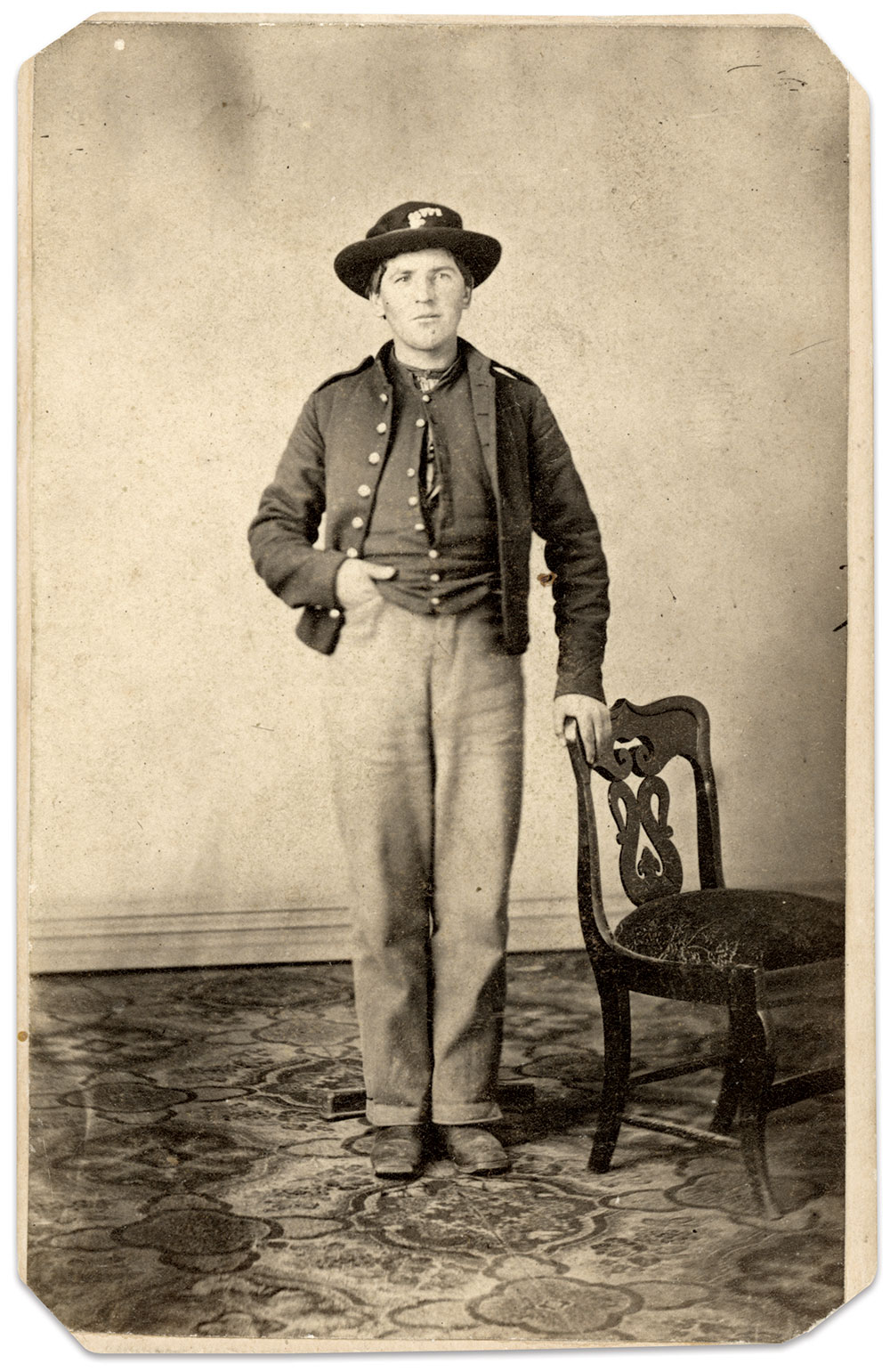

Private Henry Rice Kosier numbered among the members of Company A of the 48th Illinois Infantry who charged Redan No. 2. A 23-year-old, Pennsylvanian who worked as a carpenter in New Liberty, Ill, when he enlisted in the fall of 1861, he survived the fighting at Donelson. He was not as fortunate two months later at Shiloh, where he suffered a wound and succumbed to its effects.

Lieutenant Colonel Phineas Pease (1826-1893) commanded the 49th Illinois Infantry at Fort Donelson, a regiment organized in December 1861. Assigned to the Third Brigade of McClernand’s Division, the 49th engaged in its first fight at Donelson, where it suffered 14 killed and 37 wounded in the failed attack on Redan No. 2. Pease emerged unscathed, but suffered a severe wound at Shiloh. He survived the war, mustering out for distinguished service in January 1865. He returned to his pre-war career in the railroad industry in leadership positions with the Indiana, Bloomington, and Western Railroad; the Ohio Central Railroad; and the Cleveland and Marietta Railroad.

Colonel William Ralls Morrison (1824-1909) was no stranger to leadership. A veteran of the Mexican War, participant in the 1849 Gold Rush, and politician in Illinois, he began his Civil War service as colonel of his home state’s 49th Infantry, and commanded the 3rd Brigade in McClernand’s Division. About noon on February 13, he received orders from McClernand to charge Maney’s Battery with his 49th and 17 Illinois infantries, and Col. Isham Haynie’s 48th Illinois Infantry. Haynie, the senior colonel, might have pulled rank on Morrison. Instead, Haynie told Morrison, “Colonel, let’s take it together.” As the blue line advanced, a shot hit Morrison in the hip and knocked him off his horse. The injury ended his service. He resigned in December 1862. According to one report, Maj. Gen. U.S. Grant noted that “We lose one of our bravest officers.” In March 163, Morrison won election as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and went on to serve numerous terms.

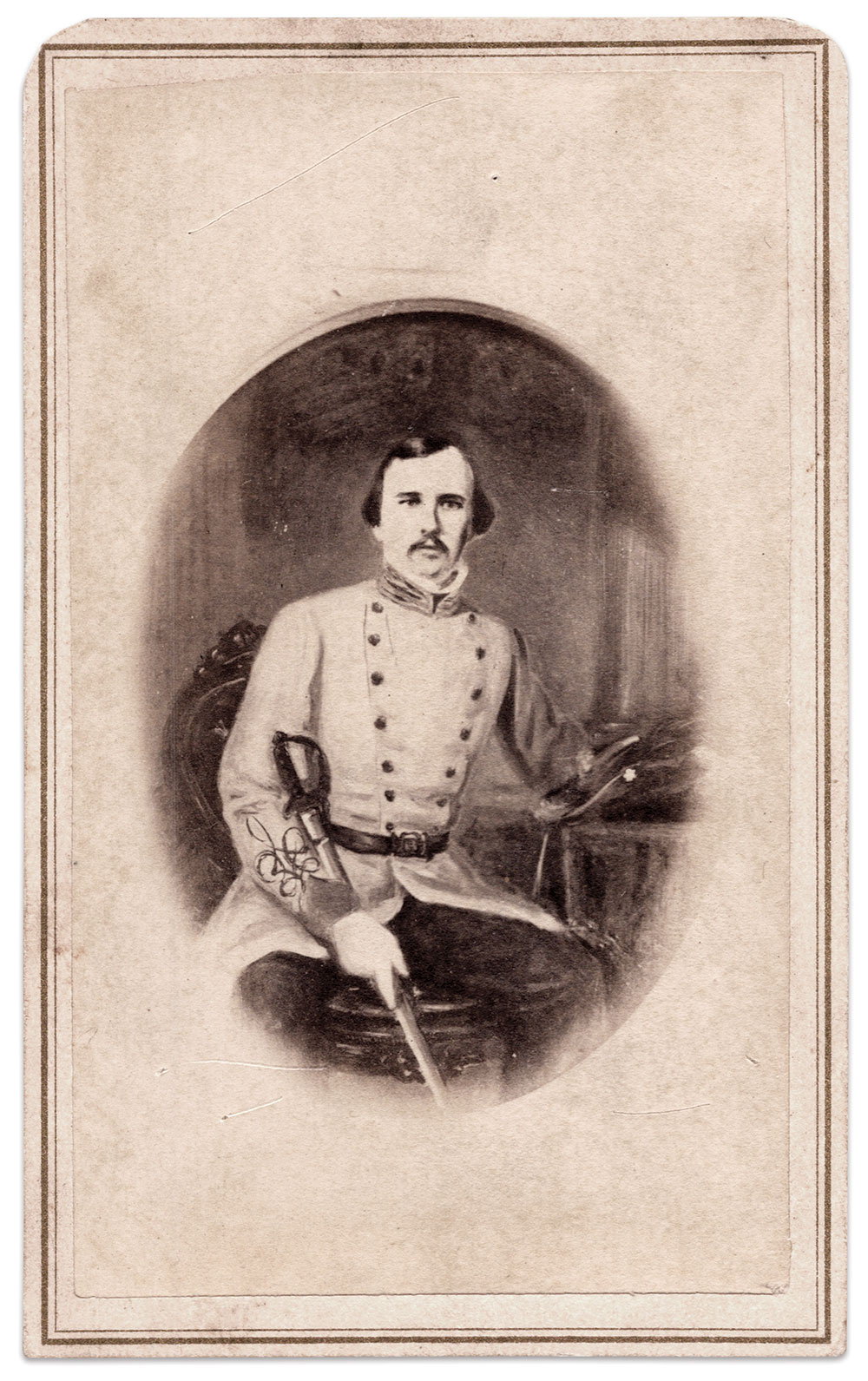

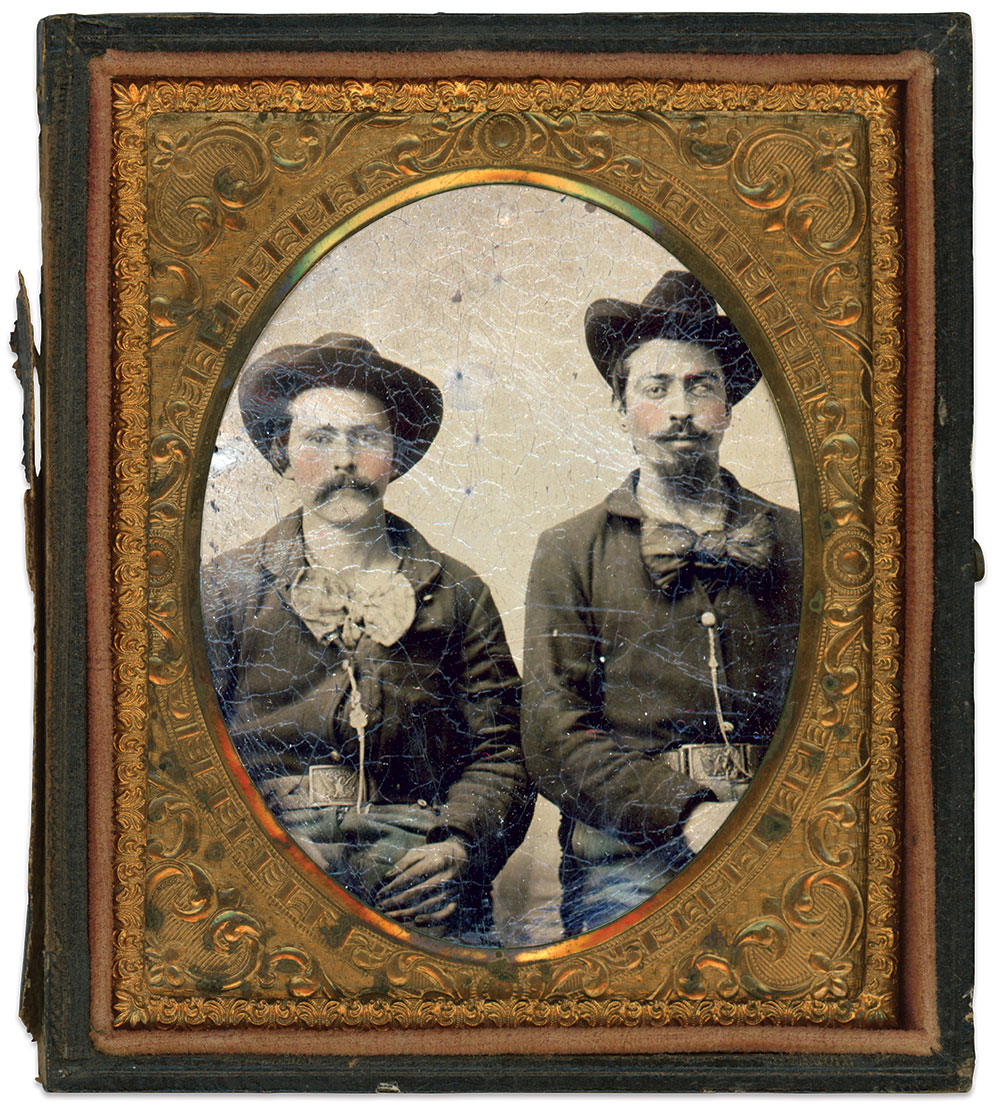

The captain of Company C of the 10th Tennessee Infantry, St. Clair McIntosh Morgan, went into the fight suffering unhealed wounds after losing a duel less than a year earlier in Florida. Morgan, the hot-tempered son of a wealthy Nashville industrialist and Confederate ammunition manufacturer, attended West Point but did not graduate. Following the surrender at Donelson, he and other officers were held at Camp Chase and Johnson’s Island, Ohio. Paroled in March 1862, there is no record of a formal exchange. Still, Morgan returned to the 10th and lost his life in the 1863 Battle of Chickamauga. He was 32.

February 14: Foote’s Flotilla Attempts a Fort Henry Repeat

At daybreak, Grant met with Flag Officer Foote to set into motion the next phase of his plan. Grant ordered Foote to take his gunboats up the Cumberland River and attack Fort Donelson. Hoping to break the Confederate resolve and believing that Donelson was weaker than Fort Henry, Grant believed victory inevitable. But Foote’s fleet could not repeat the success it had had a week earlier at Fort Henry.

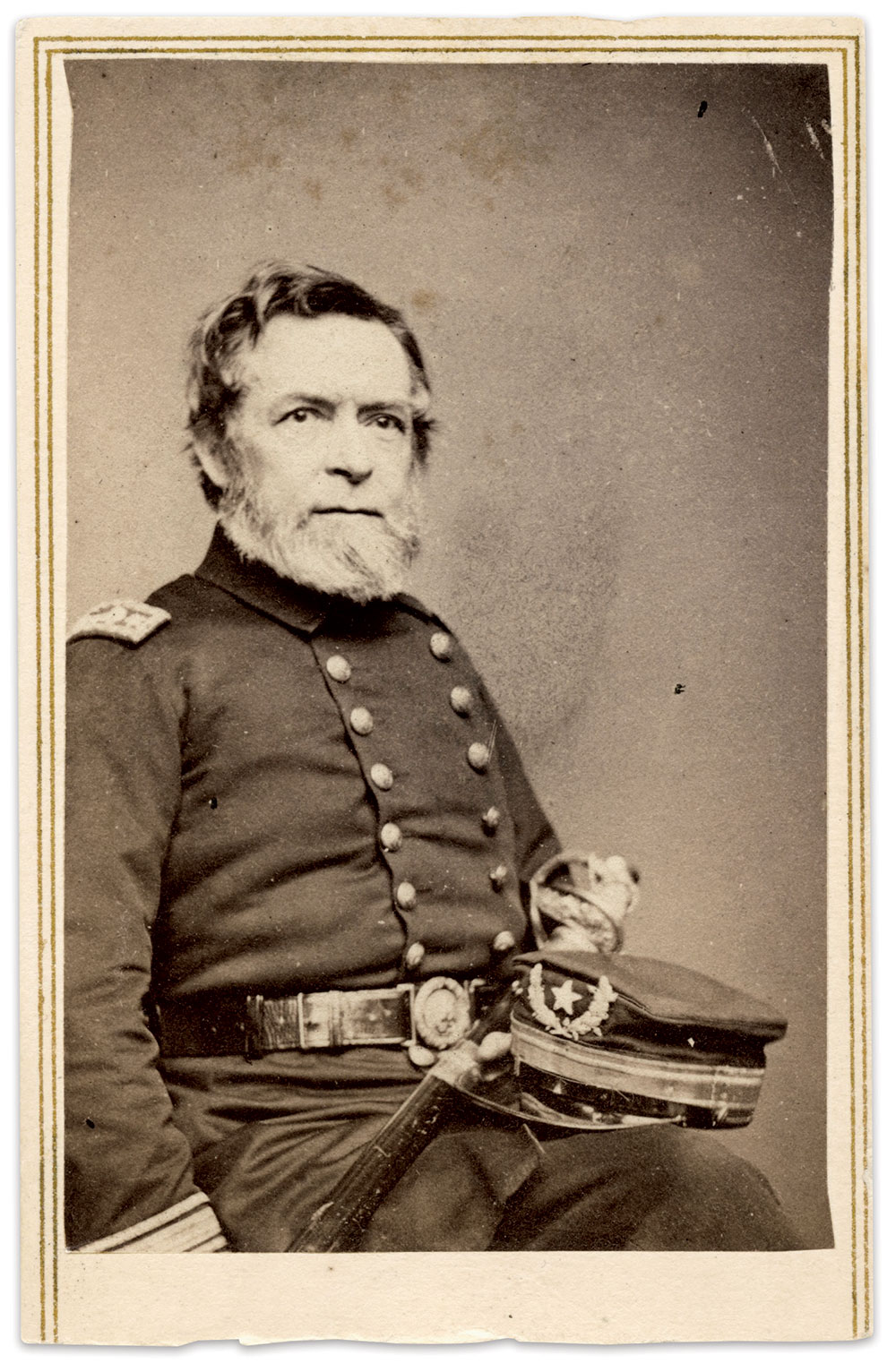

Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote’s Western Gunboat Flotilla crews, who had forced the fall of Fort Henry, opened the attack at 1 p.m. Slope-sided ironclads closed to within 400 yards of the target. According to one account of the three-and-a-half hour bombardment, begrimed, bloody and shirtless sailors said as they rammed shots into the muzzles of guns, “There’s a valentine for the gray-coats,” a grim reference to Valentine’s Day. Confederate artillerists responded in kind. One of their valentines tore into the pilot house of the flagship St. Louis, and wood splinters wounded Foote in the leg and foot.

In the end, the Union ironclads did not reduce the fort. Still, the government awarded Foote the Thanks of Congress for his actions at forts Henry and Donelson. Later, he’d receive a second Thanks for his leadership in the victory at Island No. 10, and a promotion to war admiral. But the cumulative effects of his Donelson wound, Bright’s disease, and exhaustion compromised his health. He died in June 1863 at age 56. His leadership and innovations paved the way for how the war would be fought in the West.

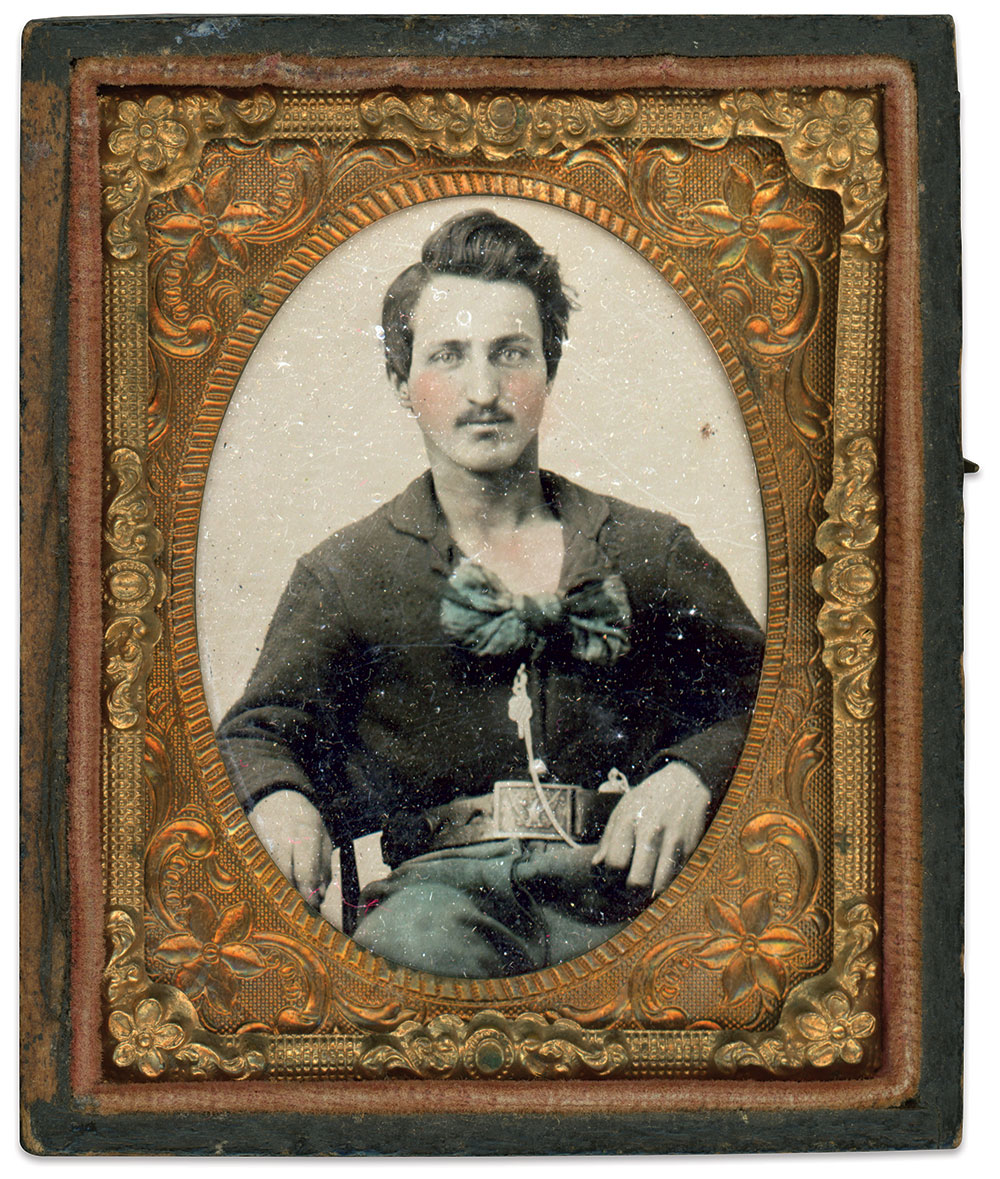

Infantrymen manned some of the heavy guns of Donelson. One of them, Corp. Daniel Clement Lyle (1842-1869), served in the 50th Tennessee Infantry. He and his Company A, along with Company A of the 30th Tennessee, had trained on the heavy guns for months. During the battle, they fired cannon in the fort’s lower battery, which included eight 32 pounders and one 10-inch Columbiad, upon Foote’s gunboats with superb accuracy. Following the surrender, Lyle and his comrades were held at Chicago’s Camp Douglas until exchanged in September 1862. The 50th reorganized immediately, and Lyle advanced to second lieutenant.

February 15: The Breakout Attack

The attack by Pillow’s forces traces back to the fall of Fort Henry. Overall commander Albert Sidney Johnston ordered Donelson’s leaders to hold Grant’s army in Dover until he could evacuate his army from Bowling Green, Ky., south to Nashville. Johnston did not want to get trapped between enemy armies.

Johnston successfully withdrew his forces, leaving Confederate commanders to extricate their garrison from Donelson, and they determined to smash into the right of the Union line held by Brig. Gen. McClernand’s Division. If victorious, Donelson’s 15,000 defenders would open the Forge Road to Nashville and join Johnston in Nashville.

Pillow launched the breakout about 5 a.m. The attack surprised McClernand’s Division and resulted in early gains for Pillow. However, Pillow and his fellow generals, John B. Floyd and Simon B. Buckner, differed about how to proceed. Meanwhile, a federal counterattack erased Confederate gains and closed the Forge Road. The fighting extended well into the afternoon and resulted in some of the hardest fighting up to this point of the war.

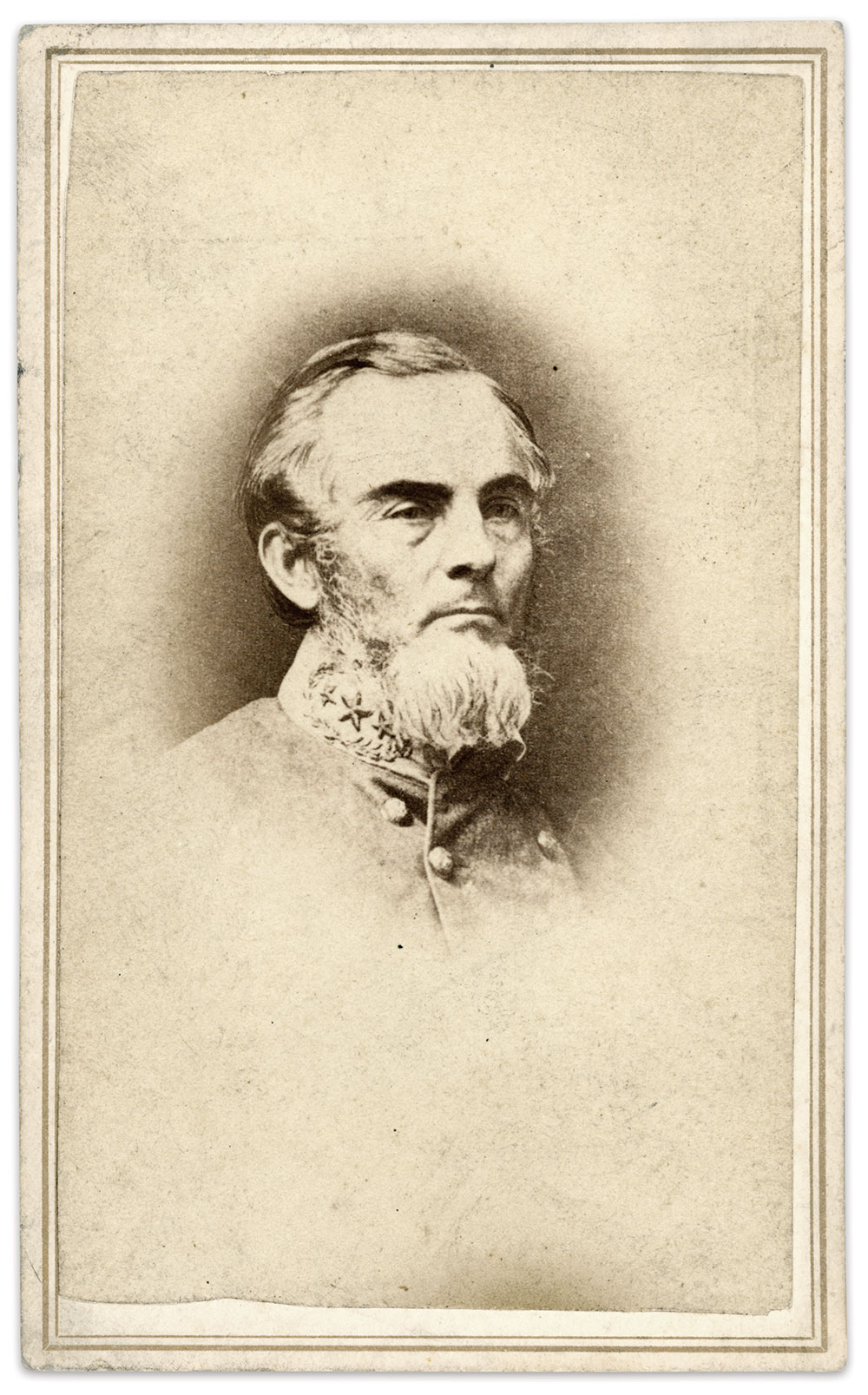

Gideon Johnson Pillow (1806-1878), the brigadier in charge of what became known as the “Breakout Attack” stirred up controversy during his military career. During the Mexican War, he publicly bad-mouthed Gen. Winfield Scott for political points. A writer with the pen name “The Citizen” defended Scott in a Nashville newspaper, calling out Pillow for his lack of military knowledge and citing an embarrassing incident of building gun entrenchments on the wrong side of a position in Mexico. “The Citizen” turned out to be Simon B. Buckner, who, at Donelson, served as one of Pillow’s subordinates. After Donelson, critics heaped blame on Pillow for failing to push the breakthrough assault and called him out as a coward for escaping while his troops became prisoners of war.

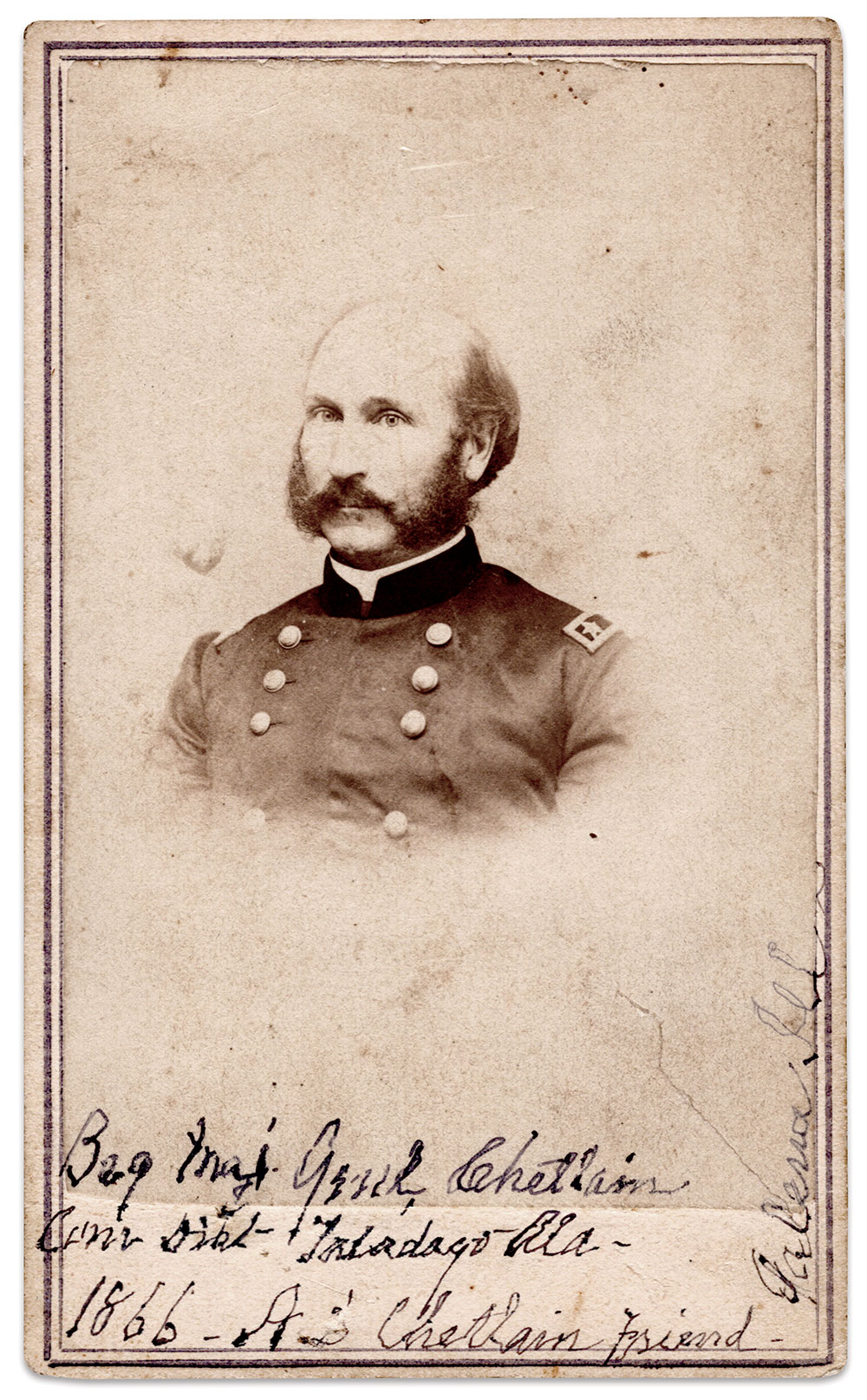

During the early morning attack, the advancing Confederate left flank ran into difficulty due in part to Lt. Col. Augustus Louis Chetlain (1824-1914) and his 12th Illinois Infantry. An early defender of the Union and resident of Galena, Ill., he was the first man to enlist in a company organized by then Capt. U.S. Grant, John A. Rawlins, and other townsmen. At Donelson, Chetlain positioned two of his companies ahead and to the right of the rest of his regiment. These men occupied buildings and a line of fences, from where they delivered well-directed fire that slowed the enemy. Promoted to colonel for gallantry at Donelson, Grant elevated him to brigadier general and assigned him the task of organizing and training U.S. Colored Troops in early 1864. Chetlain ended the war as a major general in 1866, served as a consul in the Grant Administration, and was active in business and philanthropy.

February 15: Hard Hit Wallace’s Brigade

As the Confederate attack gained momentum throughout the morning, Union troops took heavy casualties. As Pillow’s Confederates pressed the attack, the 11th Illinois Infantry and the rest of its brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. William H.L. Wallace, faced encirclement. Wallace ordered his brigade to withdraw. However, the 11th did not receive the order in time and found itself fired upon in the front and rear. As a result, the 11th suffered 320 casualties of 500 engaged, or 65 percent—the highest rate of any U.S. regiment in the battle.

Brigadier General Lew Wallace and his newly-formed Third Division were initially left behind to protect Fort Henry as Grant marched on Donelson. When it became clear that there were not enough men to surround the outer works of the fort, he sent for Wallace—a pivotal move by Grant. Arriving during the afternoon of February 14 with his untested Division, Wallace occupied the center of the Union line and sent much needed support to McClernand’s Division after it had been all but routed. Wallace, who started his war service as colonel of the 11th Indiana Infantry, went on to fight at Shiloh, become a major general, and command the 8th Corps at the 1864 Battle of the Monocacy. After the war, Wallace served as the Governor of New Mexico Territory and the military commissions that investigated the Lincoln conspirators and Andersonville’s Henry Wirz. His 1880 historical novel, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, was a bestseller.

As the Confederate advance gained momentum, Col. Richard James Oglesby (1824-1899) commanded the First Brigade of McClernand’s Division, which included his 8th Illinois Infantry. Oglesby and his Brigade were nearly enveloped by the Confederates. For nearly an hour he staved off repeated attacks, At one point, as ammunition ran low, he considered a bayonet charge. After Donelson, Oglesby became a brigadier. He sustained severe wounds at the October 1862 Battle of Corinth and ended the year as a major general. He resigned in 1864 to successfully run for Illinois governor. A significant voice in Lincoln’s 1860 presidential campaign, Oglesby showed up at the Republican National Convention with two fence rails, giving rise to the moniker “The Railsplitter.” On April 15, 1865, Oglesby was present at the Peterson House when President Lincoln died from an assassin’s bullet.

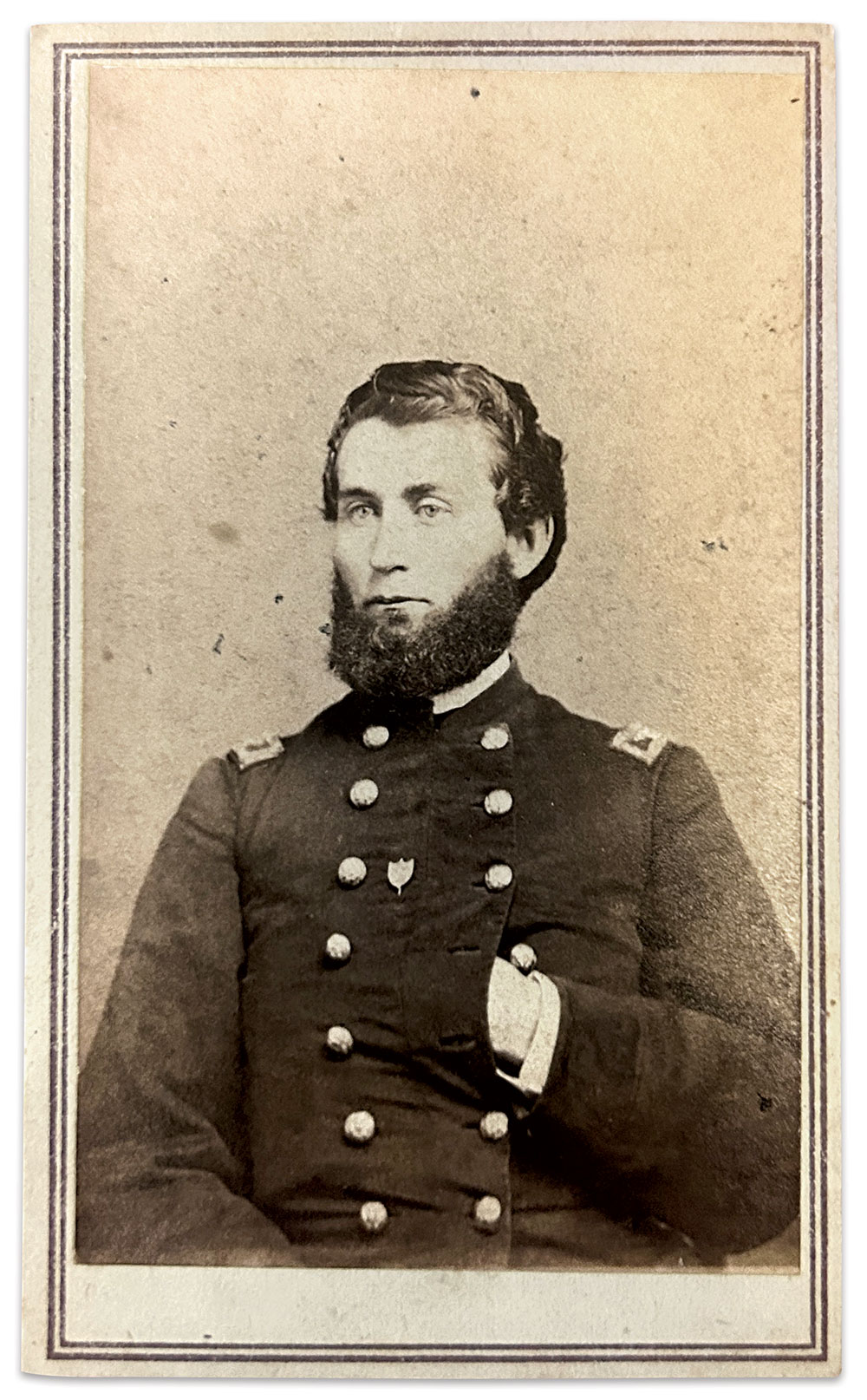

One regimental commander in Oglesby’s Brigade, Col. John Alexander Logan (1826-1886) of the 31st Illinois Infantry, distinguished himself in combat. “Black Jack,” as admirers called him for his swarthy complexion, pushed forward to support the 25th Kentucky and 11th Illinois infantries, and fought until exhausting their ammunition. At some point a bullet tore into Logan’s right shoulder and another struck the pistol in his belt, knocking him to the ground. Logan reportedly said, “Suffer death men, but never dishonor.” His rallying cry inspired his men to drive the enemy back. Logan struggled to his feet, gripped his sword with his left hand, pointed to the Confederates, and proclaimed, “Men! There is work here,” and then pointed towards the heavens and said, “There is rest there.” Carried from the field, Logan eventually recovered and went on to become a trusted subordinate of Grant and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, a politician, and a key player in the establishment of Decoration Day.

After the 31st Illinois Infantry ran out of ammunition and withdrew, Col. Thomas Edward Greenfield Ransom, 27, and his 11th Illinois Infantry continued the fight. As its ammunition depleted, the men took cartridges from the fallen and fought on until forced to withdraw. During the thick of the action, numerous bullets passed through Ransom’s clothing: six to eight by one count. One struck him in the shoulder—his second wound of the war. The son of a Mexican War colonel killed in action at Chapultepec in 1847, Ransom received a promotion to colonel for his courage at Donelson. He suffered two more wounds in battle on the way to becoming a brigadier general and division commander. Ransom died of dysentery in October 1864 at age 29.

When brigades commanded by colonels Richard Oglesby and John McArthur buckled under the enemy assault, Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace sent his First Brigade, commanded by Col. Charles Cruft, to support them. One of Cruft’s regiments, the 25th Kentucky Infantry, responded. It’s colonel, James Murrell Shackleford (1827-1909), helped drive the Confederates back. However, in the chaos and confusion of battle, Shackleford’s men accidentally fired into the rear of two brother regiments, who panicked and fled. Momentum shifted back to the Confederates and they regained the initiative and opened the all-important Forge Road to Nashville by about 10:45 a.m. Though Shackleford emerged unscathed, the rigors of campaigning compromised his health, and he left the army the following month. Shackleford went on to recruit the 8th Kentucky Cavalry, advance to brigadier general, and helped end Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s Ohio Raid in July 1863. He accepted Morgan’s surrender. Shackleford resigned in January 1864.

Captain Smith Dykins Atkins (1836-1913) led Company A of the 11th Illinois Infantry through the heaviest of the morning fighting. He took nearly 70 men into action and emerged with only 23. He received a promotion to major for his gallantry. An attorney by profession, Atkins became aware of the first call for troops in the middle of a court room during a case he was arguing. He soon canvassed the town of Freeport, Ill., to enlist 100 men who mustered in as Company A. After Donelson and Shiloh, Atkins took a two-month leave and returned as colonel of the 92nd Illinois Infantry. In February 1863, as Atkins and his new command passed by Dover on a steamer, he paused to visit a mass grave, marked with a wooden plank, which contained about 62 bodies of soldiers from the 11th Illinois that were killed on the morning of the February 15. Atkins ended the war as a brigadier general.

Colonel John Eugene Smith (1816-1897) wrote with pride about the combat qualities after his 45th Illinois Infantry charged Confederates threatening McAllister’s battery and held the position two hours. Smith noted in his official report, “mortality in the regiment was slight, which is attributed to the fact that my men never fell into confusion,” and added, “they did not flinch, but, on the contrary, maintained their ground with the most perfect self-possession and determined bravery. They fought well, did much execution, and brought credit upon themselves.” Before the end of 1862, Smith received his brigadier’s star and division command. He went on to fight in the Vicksburg, Atlanta, and Carolinas campaigns, ending the war as a brevet major general and continuing his service in the U.S. Army. One of nine Civil War generals from Galena, Ill., Smith, a son of Swiss immigrants active in city and county politics and an aide to Gov. Richard Yates, operated a silver shop near the Ulysses S. Grant family tannery.

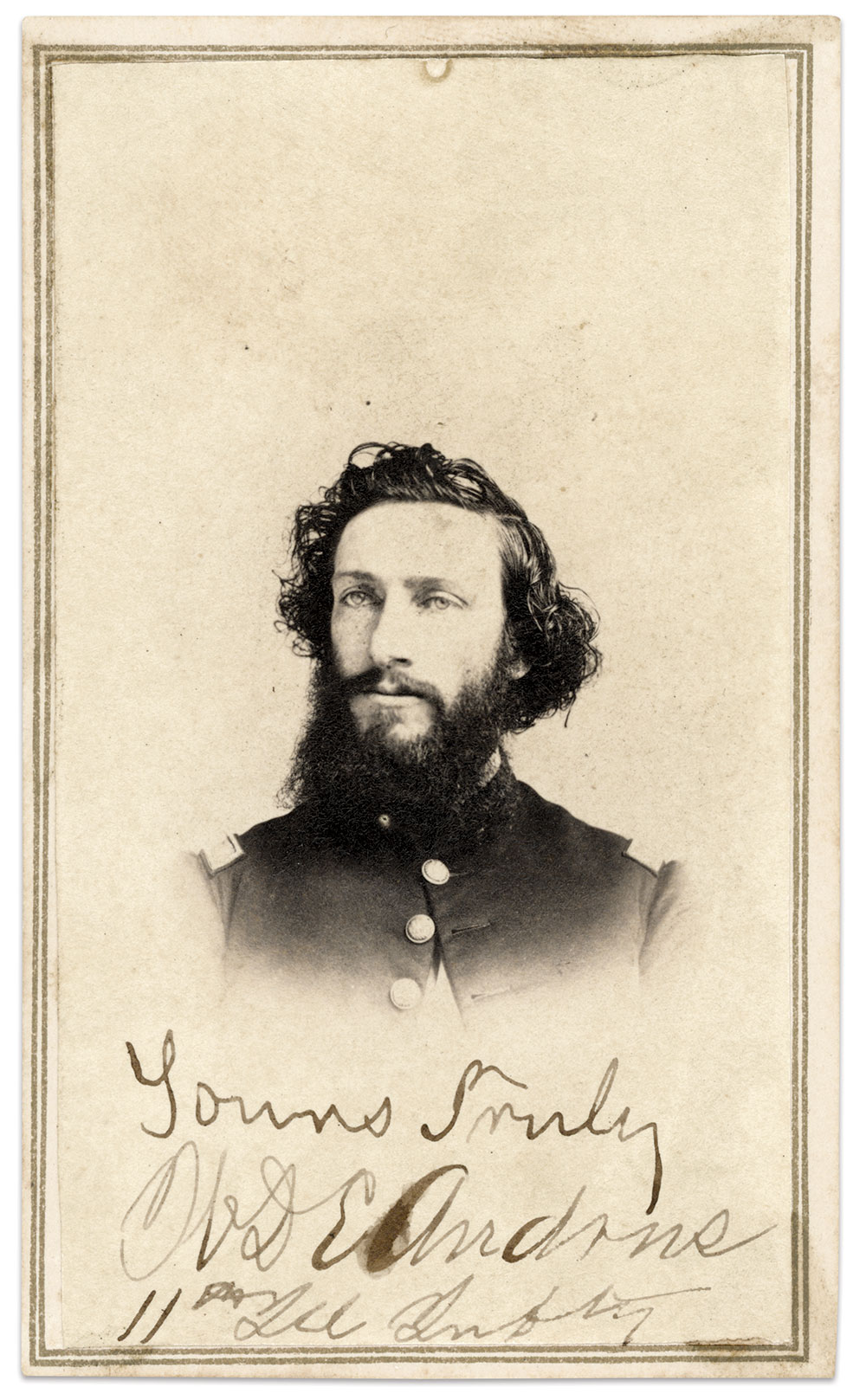

As Confederate shot and shell took a toll on the 11th Illinois Infantry, a spent cannonball struck Capt. William David Ellis Andrus (1834-1901), in the thigh. A peacetime bookkeeper politically active with the pro-Abraham Lincoln Wide Awakes organization, he joined the Rockford Zouaves, which mustered in to the 11th as Company D. Andrus survived his wound and the war. In 1866, he formed a Grand Army of the Republic Post in his hometown of Rockford, Ill., the first organized in the state. In 1878, he headed west to Dakota Territory as an Indian Agent in Yankton. He settled in Bon Homme County and founded Andrus. Today, it is a ghost town.

Yelling and screaming Confederates attacked the 31st Illinois Infantry as the men prepared morning coffee, recalled Sgt. William Samuel Morris (1842-1928) of Company C. The regiment’s colonel. John A. Logan, quickly formed the men and advanced to a crest. Morris recalled, “Here they dropped upon their knees in the snow and here at very close range they received and gave their first fire, and here the ranks were torn by canister and plowed by bullets.” The Illinoisans gave as good as they got, despite the wounding of Logan and death of their lieutenant colonel, until forced to withdraw after they exhausted their ammunition. Morris survived the fight, and the war, and went on to become an attorney and author of The History 31st Regiment: Illinois Volunteers Organized by John A. Logan.

Alfred Hamilton Lieber (1835-1876), first lieutenant in Company B of the 9th Illinois Infantry, suffered a wound in his left arm that ended in an amputation. He resigned in May 1863, and joined the 10th Veteran Reserve Corps. He completed his service as a volunteer in 1866 with a major’s brevet for Fort Donaldson. Lieber continued on in the U.S. Army until 1875, when, suffering ill health attributed to the war, he went to Europe, where he died. Prior to 1861, he dropped out of the U.S. Naval Academy to become a farmer. His father, Dr. Francis Lieber, was instrumental in codifying laws of war for the Lincoln Administration. His two brothers also served, one for the Union and another the Confederacy: Guido Norman Lieber, an officer in the 11th U.S. Infantry and the Judge Advocate Department, and Oscar Montgomery Lieber, a private in the Hampton Legion of South Carolina who died in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

William Duncan, first lieutenant of Company H of the 11th Illinois Infantry, suffered wounds in his cheek and both legs during the fight. A New York born tinner who lived in LaSalle, Ill., when the war began, he recovered from his injuries and became company captain before the end of 1862. He received his second war wound during the Vicksburg Campaign, and left the 11th in 1864. The last time his name can be found on a federal record is 1870.

During his service with the 11th Illinois Infantry, Thomas Williamson (1830-1899) advanced from sergeant to second lieutenant of Company K. He suffered severe wounds in three battles, including Fort Donelson. A first generation American born to English immigrants in Pennsylvania, he worked as a carpenter in Illinois prior to the start of the war. He mustered out of the regiment in July 1865, returned to Pennsylvania, married, and settled in New York.

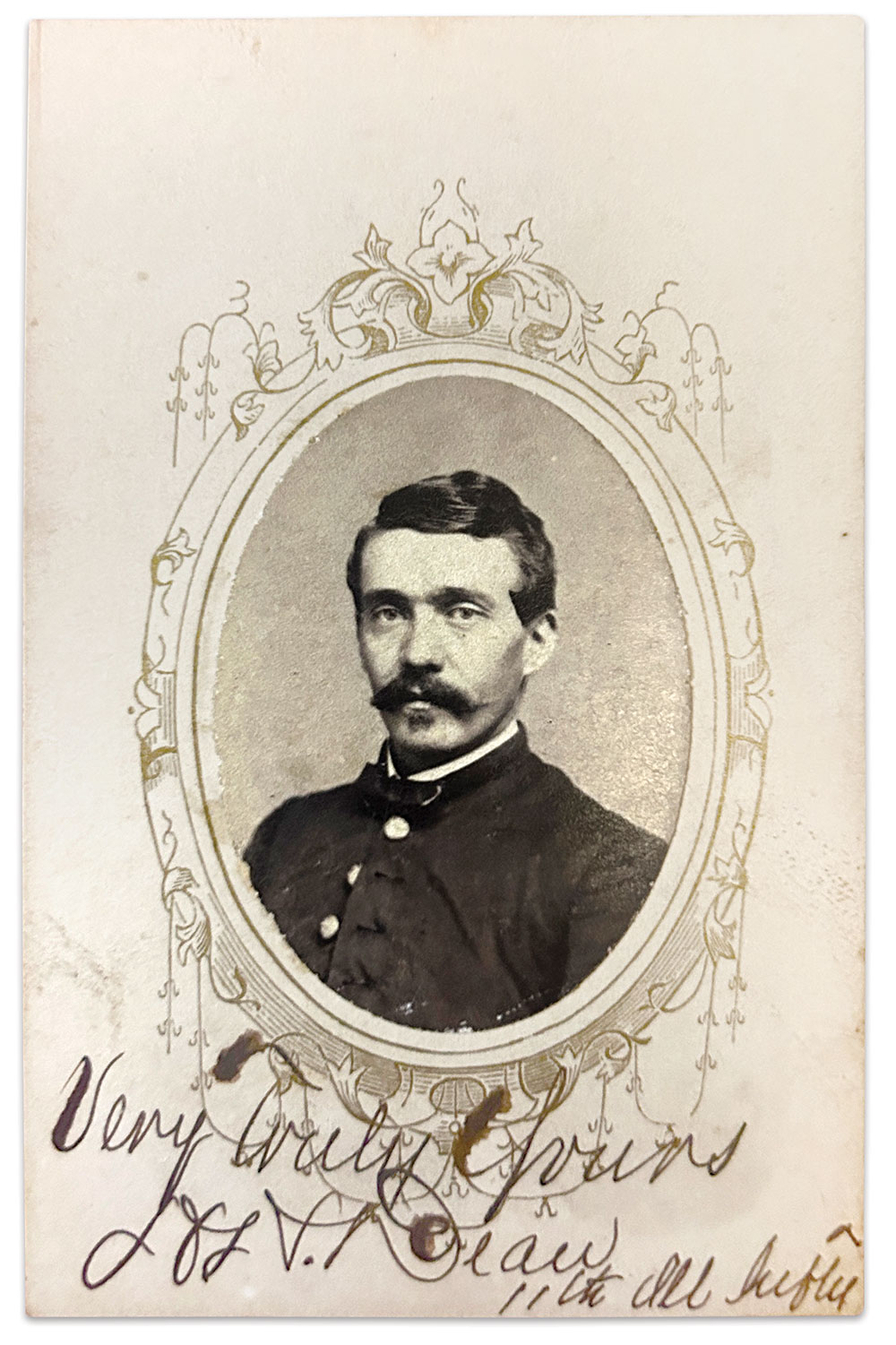

The fight took a heavy toll on the officers of the 11th Illinois Infantry. One of them, 1st Lt. Henry Hobart Dean of Company D (1837-1899), was mentioned in press reports as being badly wounded. He returned to active duty by the Battle of Shiloh, where he grabbed the regimental banner after the color bearer fell and led his men forward. Promoted to the adjutant of the 11th, Dean went on to become colonel of the 146th Illinois Infantry, and marched with his regiment in the funeral procession of the late President Lincoln.

Shot through both hips, 2nd Lt. James Oliver Churchill (1835-1910) of Company A, 11th Illinois Infantry, spent a miserable night on the frigid battlefield. His comrades found him the next morning. Churchill believed that his frozen wounds prevented him from bleeding to death. As hospital ships were filled to capacity, he ended up in Brig. Gen. Grant’s headquarters vessel, the New Uncle Sam, where Churchill refused to permit surgeons to amputate his legs. He survived and went on to become Company A’s captain. Churchill left the 11th in 1864 to join the U.S. Quartermaster’s Department, and ended his service with brevets of major and lieutenant colonel. A wartime letter he wrote describing his Donelson experience was published in 1909.

February 15: Smith’s Attack

Grant arrived from a meeting with Flag Officer Foote to find his division commanders, McClernand and Wallace, in conversation as their army slowly withdrew around them. After a most uncomfortable discussion with them, Grant surmised that the Confederates had drawn troops from the fort to support the previous day’s assault. Grant was correct. Buckner’s Division had been pulled away, leaving only a few hundred men of the 30th Tennessee Infantry to hold this portion of the outer works that lay directly in front of Fort Donelson. Grant ordered to McClernand and Wallace to reorganize their men, gather ammunition from the wounded, and stage a counterattack.

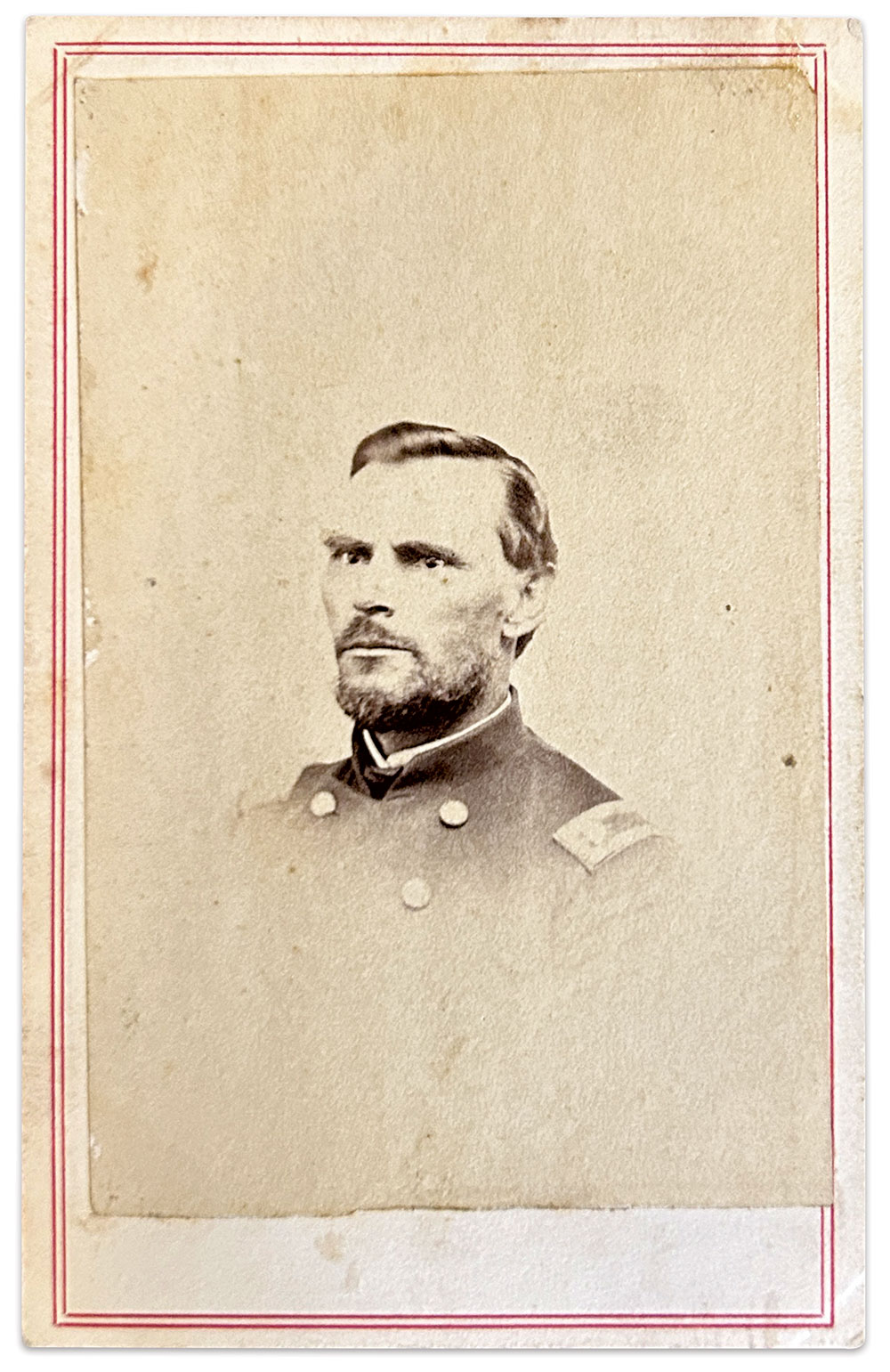

Grant then rode over to Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith’s Division, which anchored the federal left, and requested him to attack and capture the garrison. Smith launched the assault about 1 p.m., leading his division up the icy slope until reaching their outer works. Smith’s men successfully occupied Confederate trenches and seized the initiative. Fighting continued until about 4:30 p.m., as nightfall settled in.

The Division of Brig. Gen. Charles Ferguson Smith (1807-1862) advanced into the tangled mess of felled trees and abatis protecting Donelson’s outer works under a hail of enemy fire. Smith, the professional soldier and veteran campaigner, with his commanding presence and flowing white mustache, rallied the men from horseback, his voice rising above the storm of battle. “‘Damn you gentlemen, I see skulkers. I’ll have none here. Come on, you volunteers, come on,’ he shouted. ‘This is your chance. You volunteered to be killed for love of country, and now you can be. You are only damned volunteers. I’m only a soldier, and don’t want to be killed, but you came to be killed and now you can be.’” Some went to their deaths with Smith’s oaths wringing in the ears. Many career soldiers revered Smith, believing him one of the best commanders in the Union army—including Grant, his superior officer. Smith had instructed Grant at West Point, and was the only Regular Army division commander on the field. He might have played a larger role in the war, but an accidental leg injury after Donelson became infected and ended in his premature death.

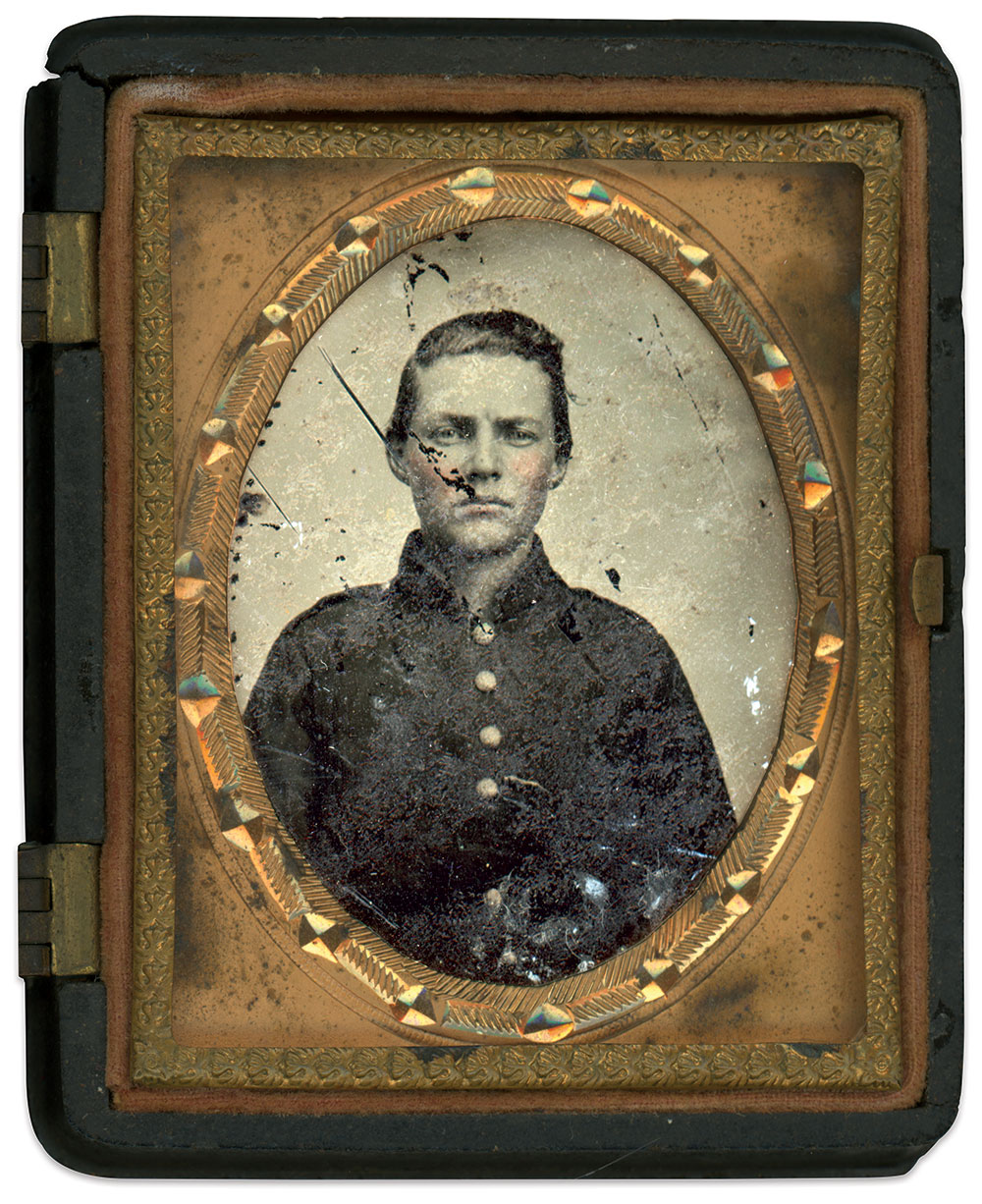

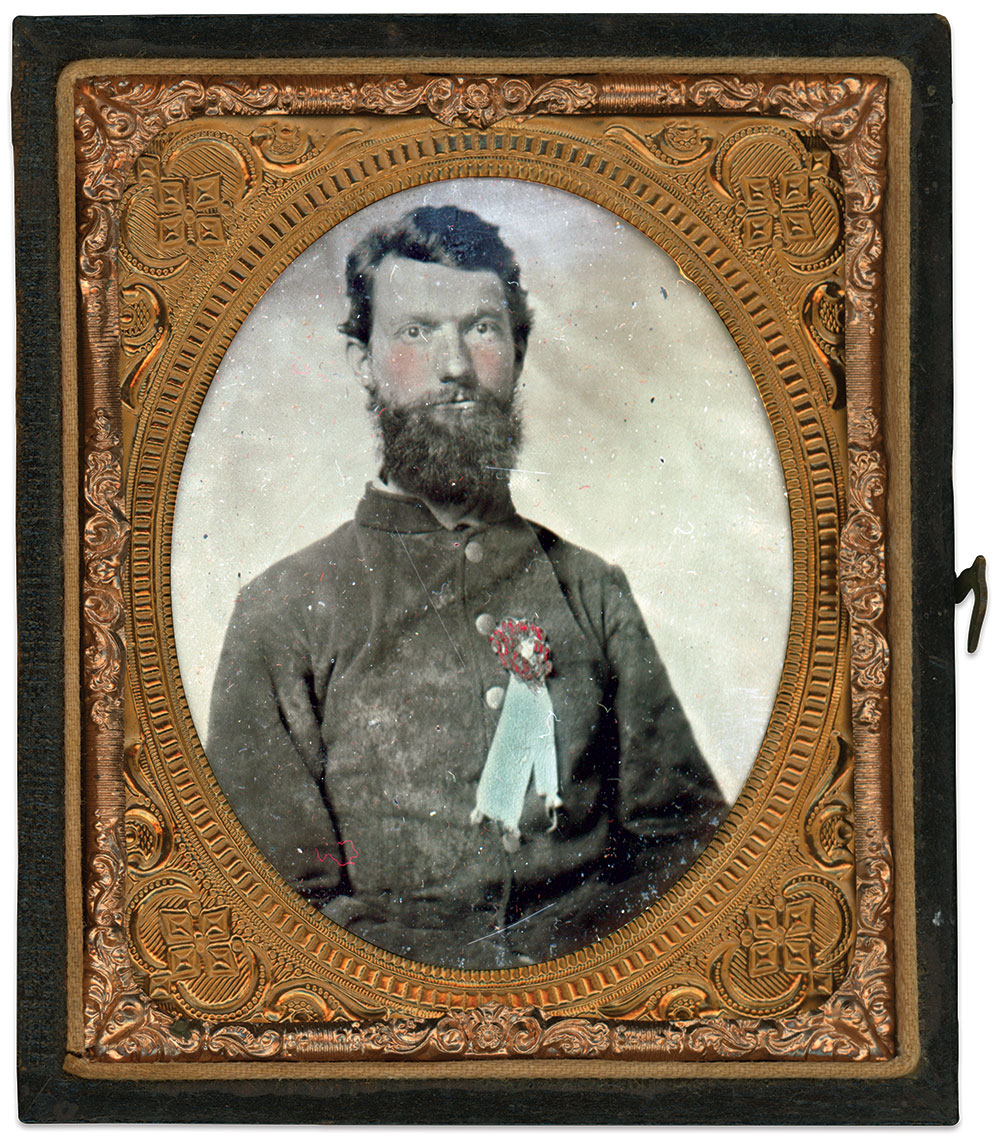

The 2nd Kentucky Infantry fought all morning before being called back to its original position in front of the fort to help repel the attack by Smith’s Division. In the ranks of the Kentuckians stood 18-year-old Private Joseph Lawrence Myers (1844-1923). Born in North Carolina, he had enlisted in Company D a year earlier. Myers numbered among those surrendered and sent to Camp Douglas. Exchanged in September 1862, he returned to his comrades. Two years later at Jonesboro, Ga., he fell into enemy hands a second time. After the war, he settled in Hickman County, Ky., married, and raised a dozen children.

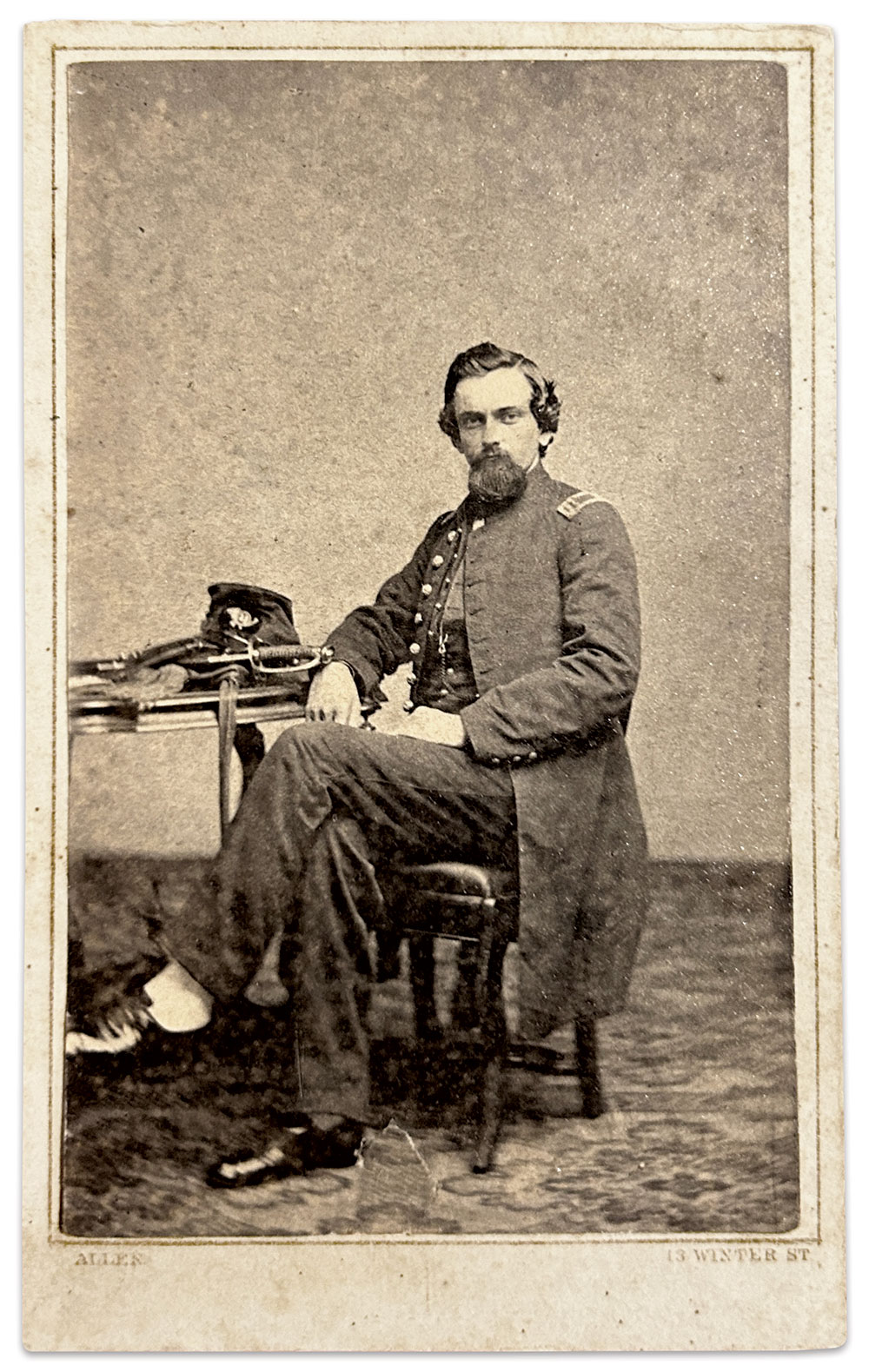

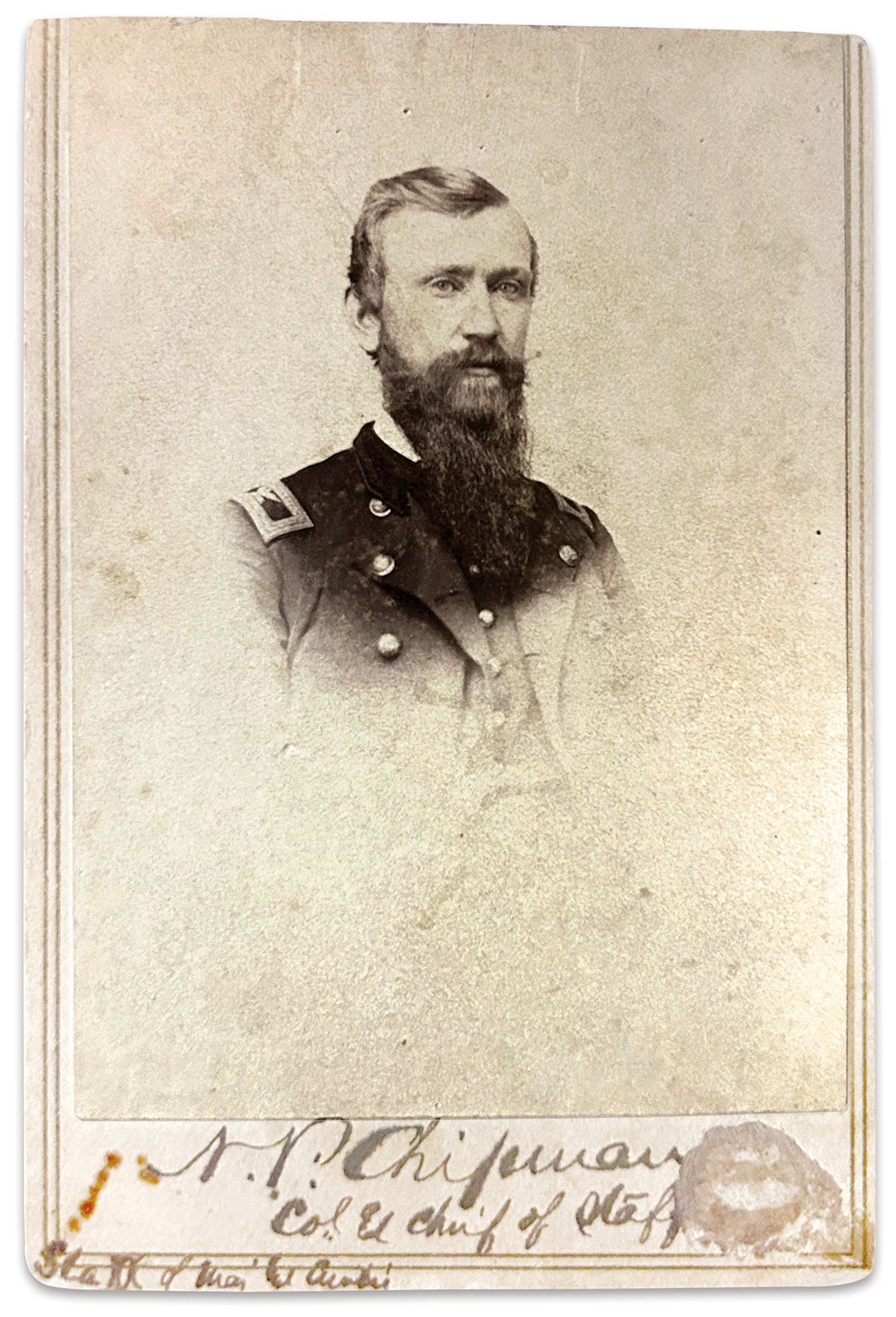

Among the first casualties of the charge of the 2nd Iowa Infantry was Maj. Norton Parker Chipman (1835-1924). Severely wounded by a gunshot to his thigh as he cheered the men on, he refused to leave the field, waving his sword and encouraging his Iowans to press the attack. Chipman recovered and became a colonel and aide to generals Henry W. Halleck and Samuel R. Curtis. Assigned to the War Department in 1864, he joined the Judge Advocate General’s Staff. Here he put his pre-war law degree to use in prosecution of Andersonville Prison’s Capt. Henry Wirz. Chipman wrote about his experiences in his 1911 book, The Tragedy of Andersonville.

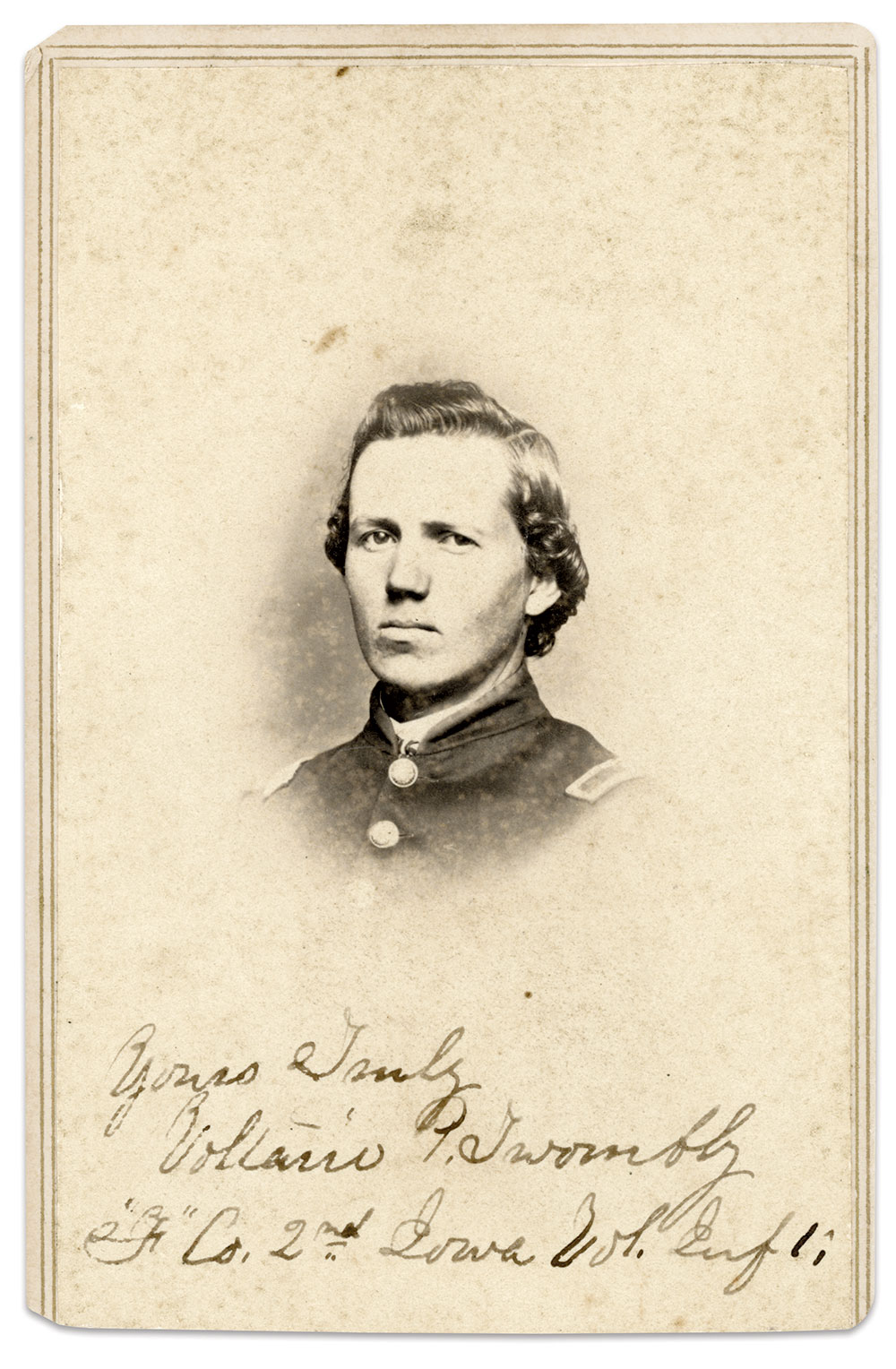

As the 2nd Iowa Infantry struggled up the icy slope leading to the outer works, Confederate defenders shot down one color bearer after another. After the fifth man had fallen, Corp. Voltaire Paine Twombly (1842-1918) of Company F grabbed the banner and carried it into the works despite being wounded by a spent ball. He received his sergeant’s stripes in recognition of his gallantry the next day. Twombly suffered two more battle wounds, at Corinth, Miss., in late 1862, and Jonesboro, Ga., in 1864. In 1897, Twombly received the Medal of Honor for Fort Donelson, making him one of two recipients of the award. The government awarded the other medal to Navy signal quartermaster and rifled bow gun captain Matthew Arther of the ironclad gunboat Carondelet in 1863.

Charles F. Smith was not pleased about having a regiment in his Division carrying rifles to which a bayonet could be attached. Such was the case with Col. John W. Birge’s Western Sharp-Shooters, later known as the 66th Illinois Infantry. Most carried Dimick rifles as they deployed as skirmishers in front of Smith Division leading up to the attack. The riflemen included Prosper Bowe (1842-1923), who served in the ranks of Company D and received credit for capturing the flag of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry. Younger brother Gilbert L. Bowe (1844-1921) joined the regiment in August 1862. Older brother Seth A. Bowe (1838-1905) fought at Donelson.

February 16: Grant’s Victory

The first surrender of a standing Confederate army had its origins inside the Dover Hotel, where Brig. Gen. Pillow established his headquarters. In a council of war held there the previous evening, generals Pillow, Floyd, and Buckner evaluated the situation. After much discussion, Buckner’s view prevailed: the men had reached the point of exhaustion and the enemy’s position made the chances of success for another breakout attempt very low if not impossible. Pillow and Floyd refused to capitulate, turned over command to Buckner, and escaped with about 3,000 troops aboard steam transports. Buckner opened up negotiations with Grant that ended with the surrender of about 15,000 men. These prisoners of war were sent to various prison camps including Camp Douglas, Johnson’s Island, Camp Chase, and elsewhere until exchanged.

While at his headquarters located in the modest cabin of the Crisp family about a mile from the Cumberland River, Ulysses Simpson Grant (1822-1885) received a note from Buckner on what terms he would have for surrender. According to one account, Grant shared the note with Brig. Gen. Smith, who twisted his white mustached, wiped his lips, and replied, “No terms to the damned rebels.” Grant laughed, pulled out a sheet of paper, and wrote out a brief response that included the words that thrust him into the national spotlight: “No terms except an immediate and unconditional surrender can be accepted. I propose immediately to move upon your works.” Grant read the sentences aloud, prompting Smith to react with “a short emphatic ‘Hm!’ And remarking, ‘It’s the same thing in smoother words.’” Buckner, in his written acceptance, declared the terms ungenerous and unchivalrous. When the two generals met to finalize the surrender, the strong declarations they made were softened by their pre-war bonds at West Point and Mexico.

Simon Bolivar Buckner (1823-1914) had known Grant from West Point and the Mexican War, where they had come of age as men and professional soldiers. According to Buckner, when they met at the Dover Hotel to formalize the surrender, his first words to Grant were to the effect of, “General, as they say in Mexico, this house and all it contains is yours.” Buckner spent five months at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. Once released, Buckner participated in the failed invasion of his home state of Kentucky and other campaigns in the Western and Trans-Mississippi Theaters. Active in politics after the war, he served a term as governor of Kentucky. He served as a pallbearer at Grant’s 1885 funeral, a recognition of their friendship and symbol of a nation attempting to heal in the wake of the late war.

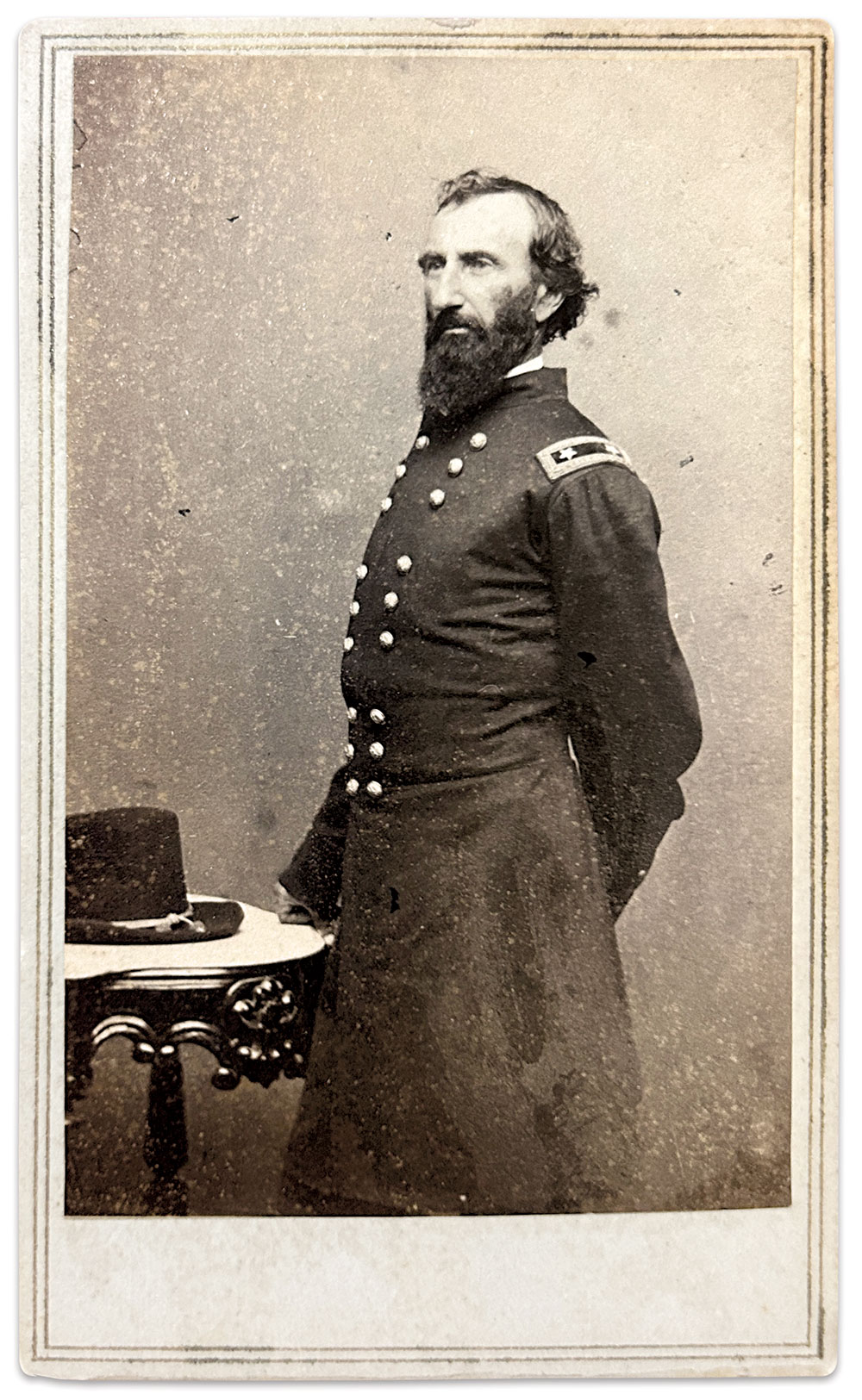

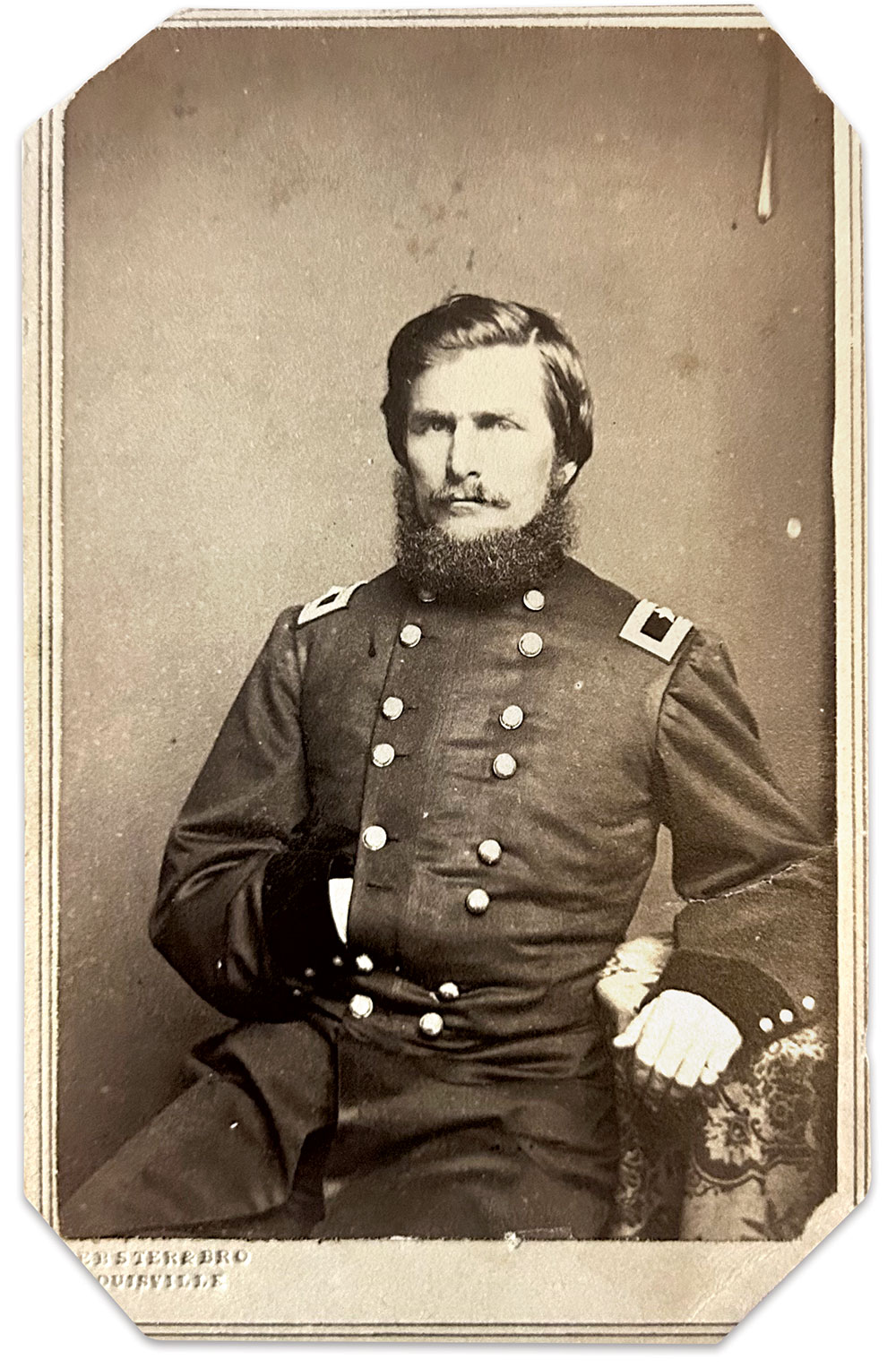

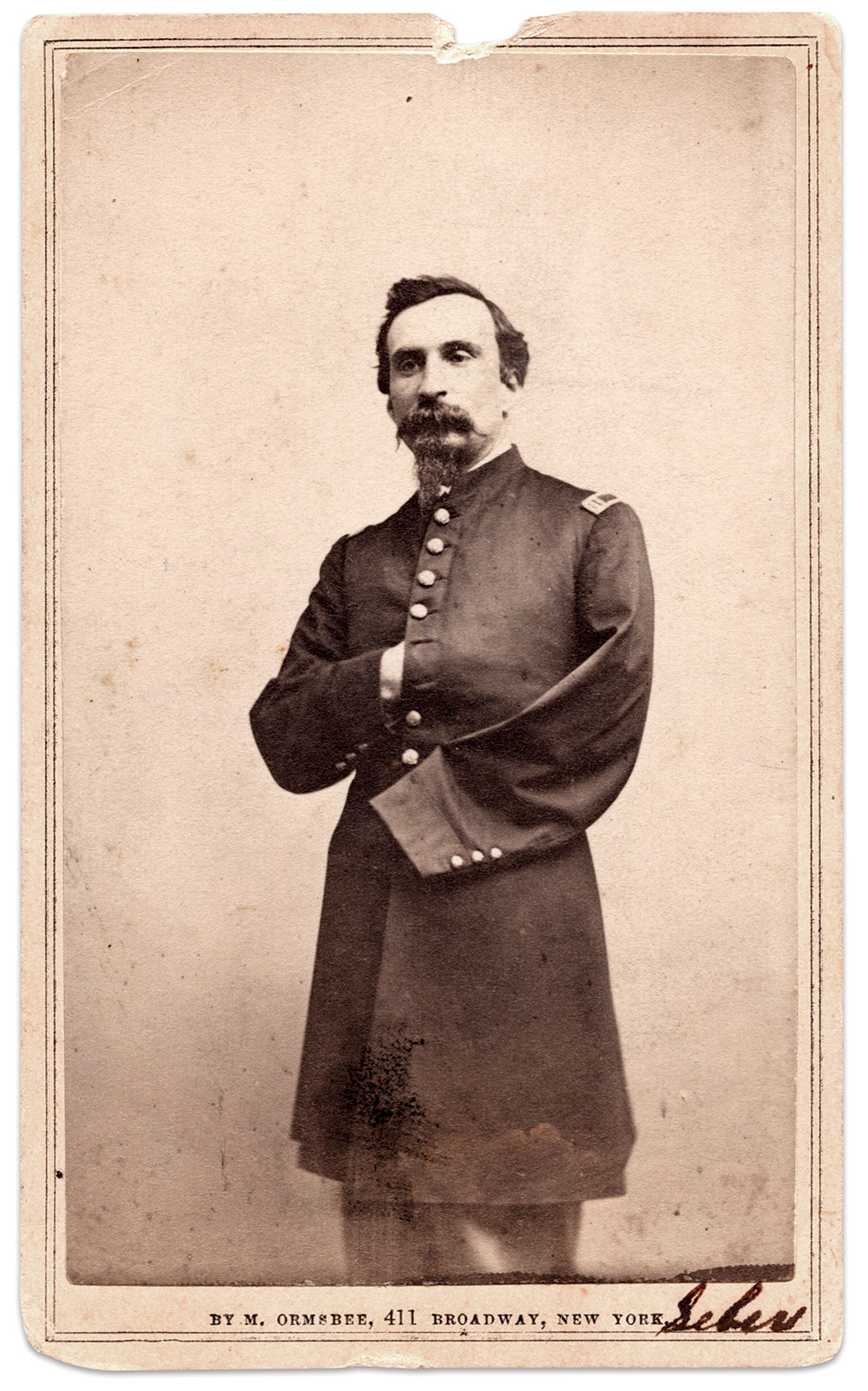

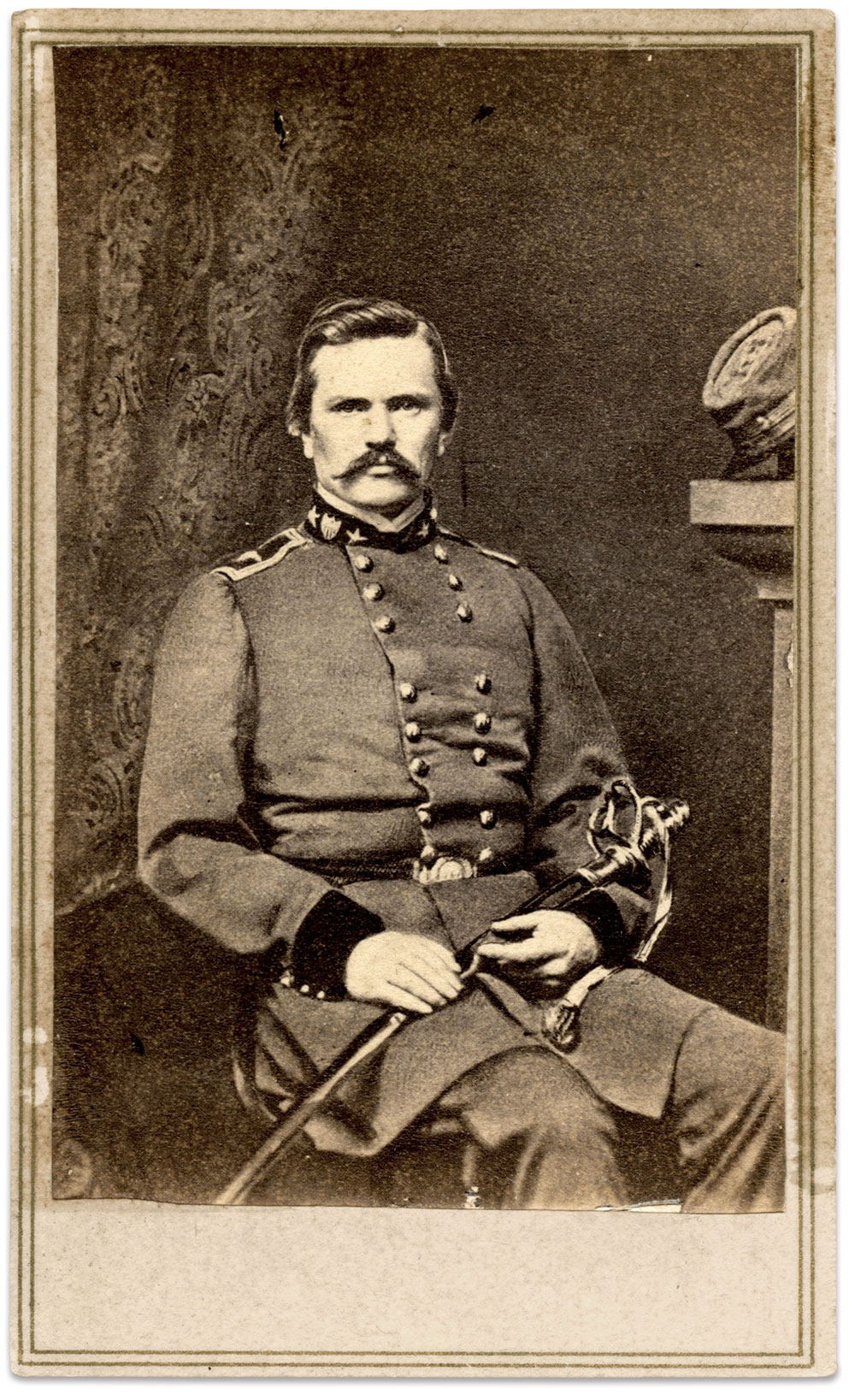

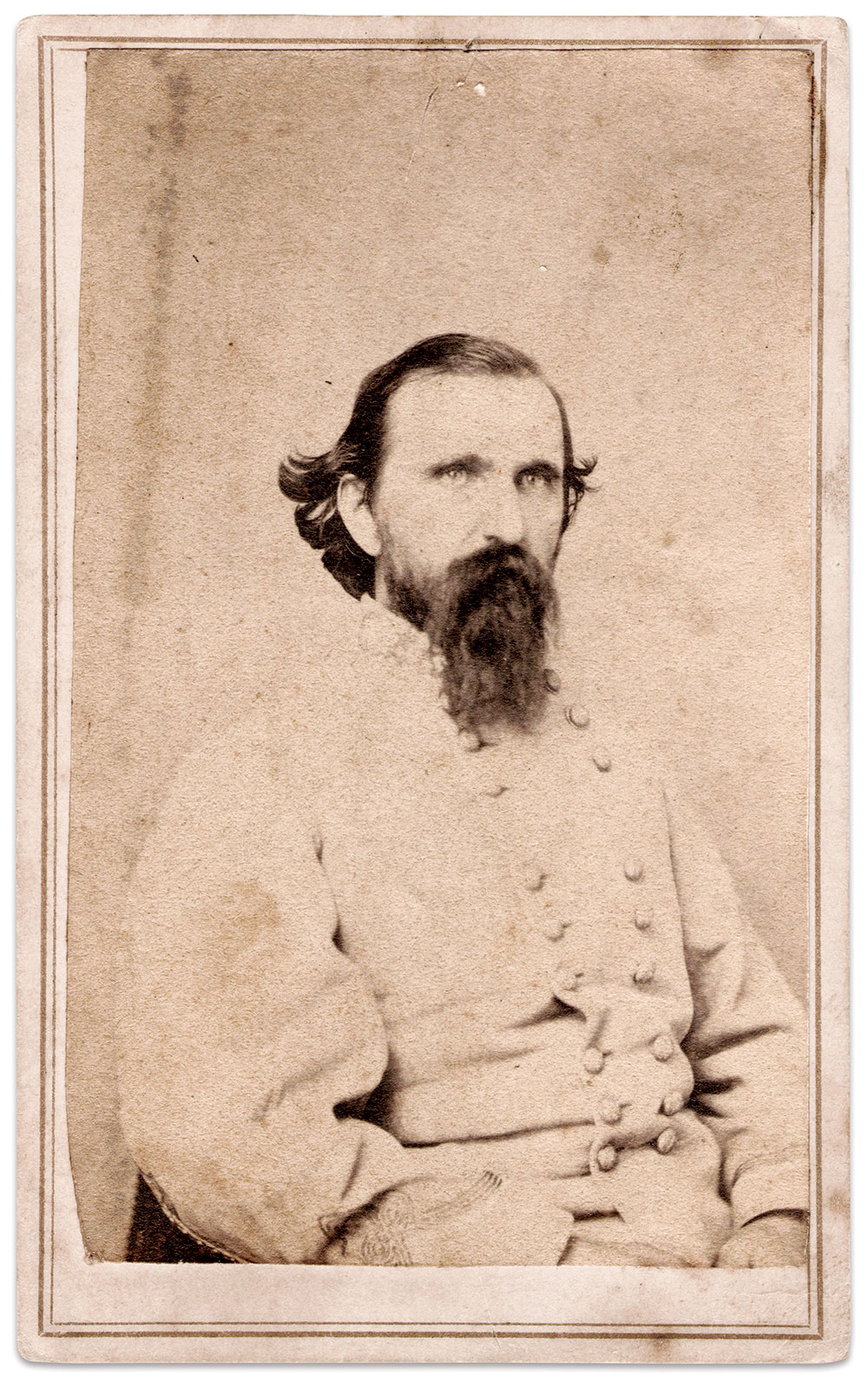

Brigadier General John Buchanan Floyd (1806-1863), worried that he would be arrested for treason if captured, made his escape in the morning. His concern may have been influenced by events in the recent past: About a year earlier, after resigning his post as U.S. Secretary of War, he had been indicted by a Washington, D.C. grand jury on charges of conspiracy and fraud. Though vilified by the press and others for his part in weakening the U.S. military as hostilities loomed, the charges were dismissed. Floyd left to become a Confederate brigadier in western Virginia, where he suffered a wound in the September 1861 Battle of Carnifex Ferry, a Union victory. Dispatched to the Western Theater and placed in command of a division, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston ordered him to assign command of the post at Fort Donelson. Having no formal military education and little experience as a soldier, he deferred to the judgment of fellow senior commanders Floyd and Buckner. He escaped from Fort Donelson with his Virginians—a move that cost his him his military reputation. President Jefferson Davis quietly relived him from duty less than a month later. Floyd’s health failed and he died in August 1863.

Floyd posed for this portrait in Knoxville just days after the surrender as he made his way back to Virginia.

Colonel John Calvin Brown (1827-1889) of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry led the 3rd Brigade, Right Wing under Buckner’s command. The previous day, his brigade had been heavily engaged in Smith’s attack. On the morning of the 16th, with Confederate high command in flux, Brown found himself temporarily in command of the right wing. According to one account, a federal staff officer brought Brig. Gen. Grant forward as he passed through the lines to meet Buckner. Grant greeted him, “Colonel Brown, it gives me great pleasure to take by the hand an officer who has made such a gallant defense.” As Grant rode away, a Confederate lieutenant approached, brandishing his revolver when Brown grabbed the bridal of the horse and asked the officer where he was going. “To shoot that damned Yankee officer, and now let loose of my bridle or I’ll shoot you.” Brown drew his own pistol and aimed it at the lieutenant, commanding him to “Drop that pistol”. It is not known if Grant ever learned of this incident.

Captain Gus A. Henry (1838-1882), assistant adjutant general on Pillow’s staff, numbered among those who escaped before the surrender. Just a week earlier, on February 9, Gus had issued General Order No. 1 in Pillow’s name from his headquarters at Fort Donelson. It announced Pillow’s assumption of command, and called on the troops to defend the post and restore the Confederate banner over Fort Henry with the battle cry “Liberty or Death!” Fort Henry was named for Gus’s father, respected politician Gustavus Adolphus Henry Sr. Gus had been an aide to Pillow since the previous year, and had two horses shot out from beneath him at the recent Battle of Belmont. Following Donelson, he went on to serve in various administrative roles ending his service as lieutenant colonel and Inspector General of the Army of Tennessee.

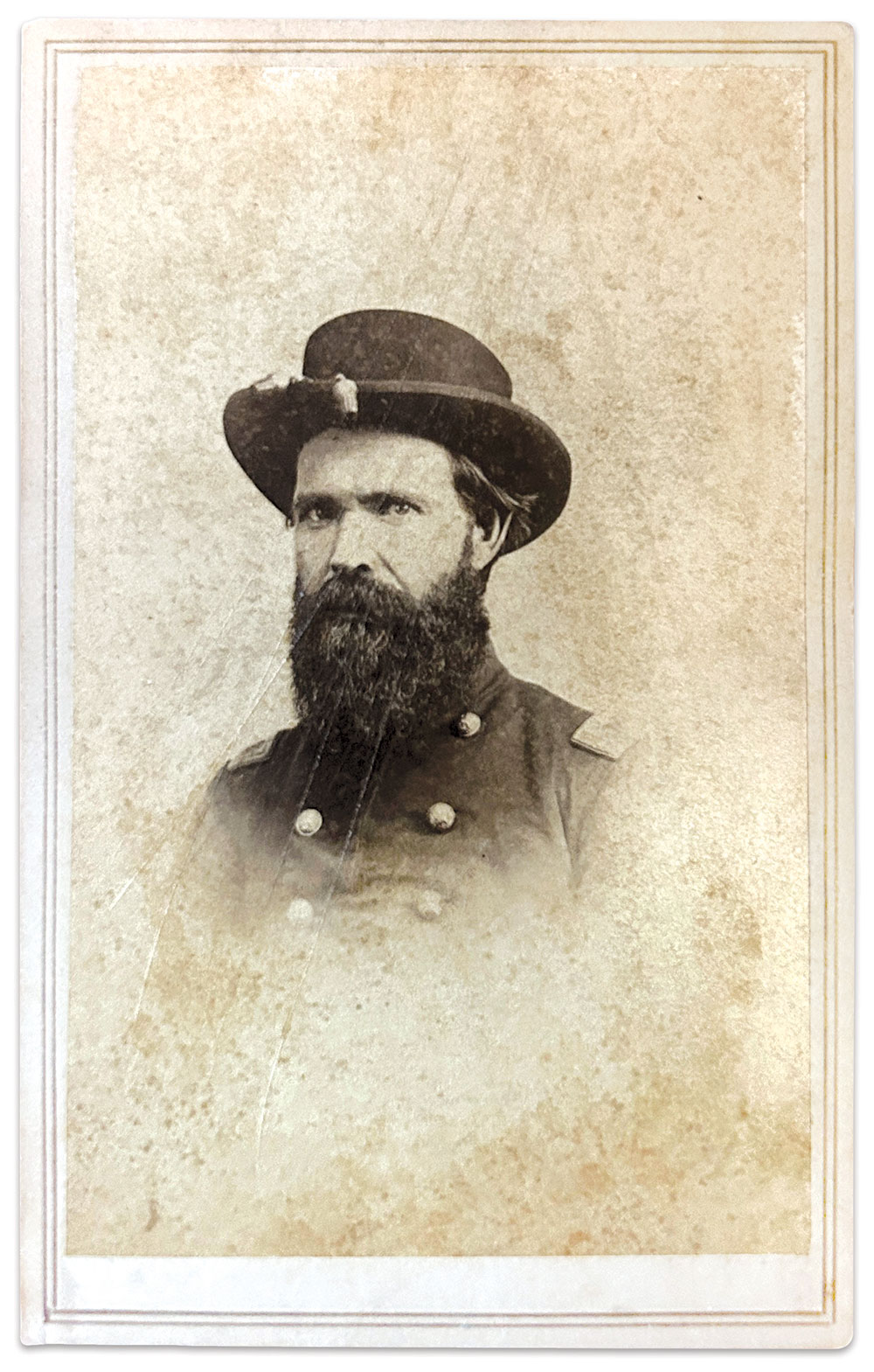

Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877) and his 3rd Tennessee cavalry proved its fighting mettle as shock troops, running flanking maneuvers, and carrying ammunition to the infantry that advanced faster than the Ordnance Department could keep up. As ammunition dwindled and the attack lost momentum, reported the Memphis Daily Appeal, Forrest’s cavalry appeared. “A thrill of joy went to the heart of every man who saw them. As they came up, with one wild shout we all advanced together, the enemy retiring beyond his battery.” Despite the show of force by Forrest, and his belief that he had the Union army on the run and the verge of a rout, he could not convince generals Pillow and Buckner to continue the attack. Rather than surrender the next day, Forrest and his men escaped. His independent streak and fighting spirit launched a storied military career that elevated him to lieutenant general and department command by the end of the war. His connection to the killing of U.S. Colored Troops at Fort Pillow, Tenn., in 1864 and association with the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction stirred controversy, but did not detract from admirers who branded him “The Wizard of the Saddle.”

After the surrender, Birge’s Western Sharpshooters and other regiments occupied Fort Donelson. Their number included 18-year-old Pvt. Charles F. “Charley” Kimmel (1843-1930), who took possession of abandoned Confederate mail. A German-born resident of Dayton, Ohio, he participated in 34 actions during the war, and suffered four wounds: one in Mississippi in 1862 and three during the Atlanta Campaign. He ended his service as a sergeant in 1865. Returning to Dayton, he worked as an express wagon driver and laborer, married, and raised a family of eight. He and his wife, Catharine, named their four boys for Union leaders: Ellsworth, Garfield, McPherson, and Sherman. Proud of his service, he wrote of his experiences using the pseudonym “Old Gunboats.” Politically a Democrat, he enjoyed meeting Confederate veterans. His life might be summed up in a verse that appears in several of his writings:

We are the boys from Illinois,

although we are far from home;

We are the boys who fear no noise.

And we hail from the Sixty-sixth Illinois

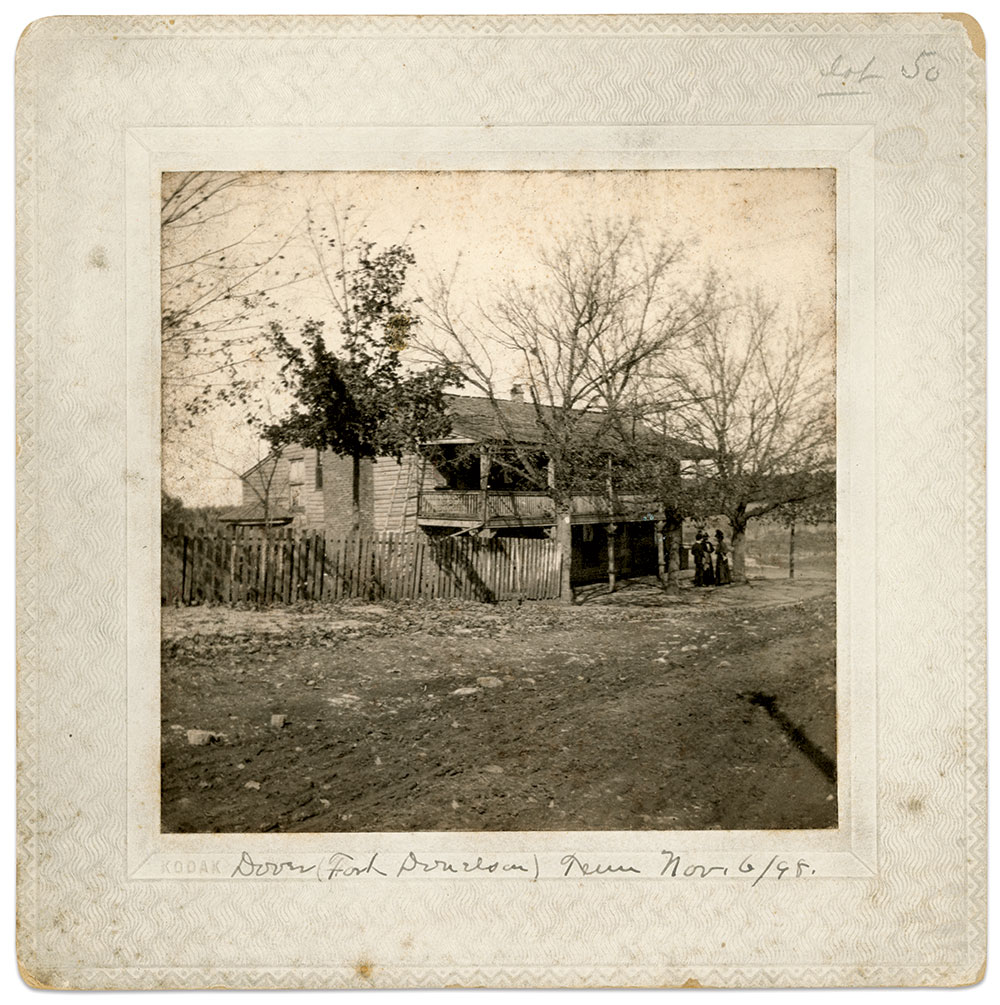

The Dover Hotel, pictured here in 1898, is the only structure in the town standing that had seen all four years of the war. Built between 1851-1853, it included eight boarding rooms on the second floor. During the battle, it served as Pillow’s headquarters, and generals Buckner and Grant met here to sign the surrender. It was used as a hospital after the battle. Falling into disrepair by 1927, a group of ladies formed the Fort Donelson House Historical Association and opened it as a museum in 1930. The Association donated it to the National Park Service in 1959.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.