By Ronald S. Coddington

The painted backdrop visible in portraits taken by a young photographer honing his craft in Washington, D.C., is the focus of this installment. During the war, the national capital experienced significant growth from the center of a small federal government with Southern influence to a greatly expanded center of military activity.

Census figures reveal that Washington contained about 75,000 residents in 1860, making it the 14th largest city in the country. In 1870, 132,000 souls were enumerated, and it had slipped to 15th place. However, its growth rate over this 10-year period of 75.4 percent was the highest in the East and fourth in the country, ranking behind Chicago, San Francisco and St. Louis.

During the war, estimates suggest that between the census counts 150,000-200,000 people lived in Washington: government workers, military personnel, relief workers, and freedmen.

The rapid expansion stressed local resources and created new and exciting business opportunities, including photographers eager to capture the faces of soldiers and civilians.

The photographer

One of the youngest photographers in the bustling capital got his start in Baltimore: John Wallen Holyland. Born in New Jersey to English immigrants, he and his family moved to Baltimore, where his father, Charles, worked as an engraver and engineer. Young John had an interest in fine arts and painted landscapes, seascapes, and birds. A trip to the Minnesota frontier with an uncle fueled his passion. At some point he discovered a passion for photography. At age 19, in late 1860 or early 1861, photographer John H. Young hired him to work in his Baltimore gallery. Here, Holyland learned the craft from the experienced Young, a pioneer daguerreotypist.

At some point during the early part of the war, Holyland’s father purchased a gallery for his son, located in Washington at 250 Pennsylvania Avenue, just a couple blocks from Brady’s studio. A biographer noted, “An average inexperienced youth would have been utterly discouraged and led to abandon the undertaking in despair; but the difficulties to be surmounted served to give new zest to his pursuits of the requisite knowledge to constitute him a skillful artist. Through the day, and far into the night, he experimented and toiled, until at last success crowned his efforts.”

A newspaper report in the Jan. 27, 1864, Washington Chronicle described Holyland as an “eminent photographer.” The same report describes an oil portrait of President Abraham Lincoln painted by Holyland. The full length view of Lincoln pictures him leaning against a column holding a scroll of paper inscribed “Proclamation of Emancipation.” According to the report, “The President did not sit for this picture, but the painting has been executed from observations made on various occasions, and it is from this fact that much of its care and grace is derived.” The whereabouts of the painting today is unknown.

Following Lincoln’s assassination, the late President’s bodyguard, about 80 members of Company K of the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry, posed for their cartes de visite in Holyland’s gallery and presented an album of them to Tad Lincoln. Today the album is in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

After the death of his father in the autumn of 1865, Holyland, who had recently married, returned to Baltimore. He purchased the studio of the man who gave him his first photography lessons, John H. Young. Holyland operated the gallery into the late 19th or early 20th century. In 1911, one writer noted that Holyland’s portraits were part of many Baltimore family records that “helped to hook our generations together.” Holyland died in 1931 at age 89.

The backdrop

at the Library of Congress.

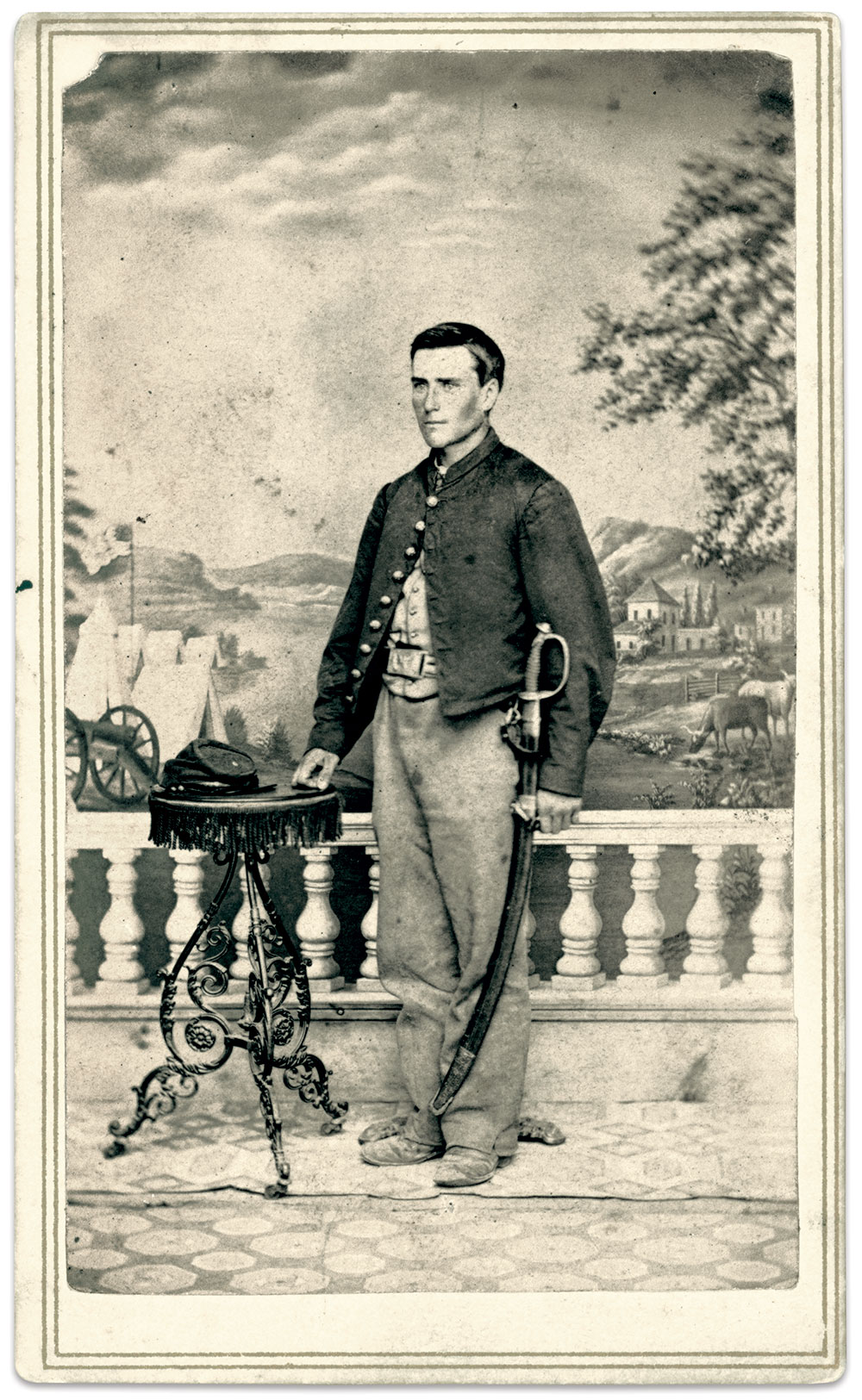

Considering Holyland’s artistic impulses, he may have painted this backdrop. It could be titled “War and Peace.” A wide river twisting its way to distant mountains divides the canvas into two sections. On one side, the U.S. flag waves over tents that spread to the edge of the banks of the waterway. A field cannon in the foreground is aimed at a target outside the visible area. On the other side, a pastoral scene features a well-appointed home and outbuildings nestled in a landscape of shrubs and trees. A sailboat floats in the river. In the foreground, two horned cows, one dark and another light, graze and drink from the water.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.