By Jack Hurov

The Summer 2024 issue of Military Images magazine featured Evander M. Law and his staff on the cover. Current evidence suggests the half-plate ambrotype was taken by an, as yet, unidentified photographer during the summer of 1864.

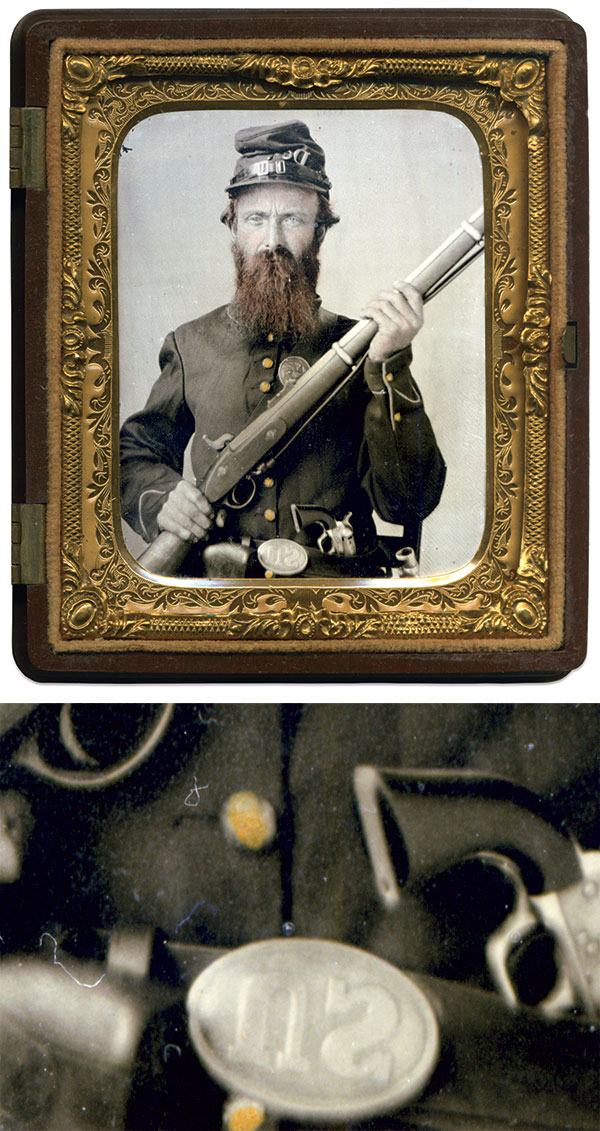

Sharp-eyed readers noted that Law’s double-breasted uniform coat is partially fastened on the side opposite that of his staff (see Mail Call in the Autumn 2024 issue). One significant feature of hard-plate images—ambrotypes, daguerreotypes and tintypes—provides an explanation. When processed, each of these was a mirror image of the sitter. This reversal applied to the sitter’s posture and uniform details, as well as to all features visible within the image. For example, the raised letters US, seen on Civil War-era oval waist-belt plates appear in reverse with the S as the first letter and U as the second letter.

Thus, if one holds the cover of the Summer 2024 issue to a mirror, the reflection is the way Law and his staff looked, seated before the photographer. A mid-19th century sitter, aware of this reversal, would occasionally wear their waist belt upside down resulting in upside down and reversed US with the U first and S second.

Though this adjustment resulted in the U being on the apparent right hand side of the sitter’s accouterment plate, the adjustment was not without problems.

Law apparently fastened his coat using the left hand row of buttons, in contrast to his staff, who fastened their double-and single-breasted coats on the right-hand sides. Moreover, Law’s left hand rests upon his lap, his right leg is crossed over the left, and he parted his hair on the right.

The Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Army of the United States, June 1851, (reprinted in 1858 and 1861), stated that among commissioned officers, captains and lieutenants shall wear single-breasted coats, and double-breasted shall be worn by all other grades. The Regulations do not specify whether double-breasted coats shall be manufactured with corresponding double rows of button holes. Thus, while the presence of double rows of coat buttons was indicative of rank, were they merely formal, or were they also functional? Moreover, the Regulations did not specify that single-breasted coats shall be manufactured with buttons sewn on the right side, though that was, and continues to be, the convention for men’s clothing, with corresponding buttonholes sewn on the left.

In this essay, I address readers’ interest in the manner in which Law’s coat is buttoned, and investigate three related questions. First, were double rows of buttonholes sewn into army and navy officers’ coats, corresponding to the double rows of buttons? Second, if double-breasted uniform coats were manufactured with two rows of buttonholes, did officers choose to button their coats on the left side? And third, are there examples of single-breasted uniform coats manufactured with buttons on the left?

The raw material

I reviewed a convenience sample of Military Images, published from Winter 2014 through Spring 2024 (42 issues), seeking photographic evidence that might answer the above three questions. I reviewed hard plate images and cartes de visite, those paper images printed from glass plate negatives. When processed, cartes yielded positive images of sitters; that is, as they appeared in life, posed before the photographer. Contributed images, as well as those in advertisements, were reviewed. An 8x loupe was used to confirm button and buttonhole placement, according to the following methodology:

A minimum of three button-holes had to be visible on the left and right sides of a uniform coat to confirm it was double-breasted (Figure 1); and, a minimum of one button had to be fastened on the left side of either a double- or single-breasted uniform coat to be tabulated as having been thus buttoned (Figures 2 and 3, respectively). Uniform coats satisfying these criteria were tabulated, regardless of the rank of the wearer.

Collection.

Collection.

United States (U.S.) and Confederate States (C.S.) double- and single-breasted coats, and the manner in which they were buttoned were tabulated separately, producing six categories. Within each of these categories, the numbers of Army (A) and Navy (N) uniform coats, as well as hard plate images were noted. Survey results are presented below as horizontal bar graphs, scaled to reflect the number of photographs within each category.

Survey results

Buttons, buttonholes and the photographic evidence

Based on the photographic evidence, it seems reasonable to conclude, though cautiously, that double-breasted uniform coats, while indicative of rank, were made with two rows of functional buttonholes. Such an arrangement permitted the wearer to fasten the right or left row of buttons.

In Law’s case, he may have buttoned his coat on the left due to a left arm injury, sustained at the First Battle of Manassas. Moreover, double rows of button holes provided the wearer with an additional measure of comfort since he had the option of opening and securing both lapels, as Law did. Could such ‘reverse buttoning’ also be indicative of left- or right-handedness among their wearers?

The prevalence (19:7) of federal naval officers wearing their double-breasted coats open, thus exposing the two rows of buttonholes, is in contrast to their more formal army counterparts. Perhaps naval officers felt at ease from the strictures of life aboard ship when in front of a photographer.

The fact that total U.S. images in this survey outnumbered C.S. images by just over 2:1 is in keeping with the numerical superiority of U.S. soldiers and sailors, as well as with scarcity of photography supplies available in the South, particularly as the war went on. Hard plate images frequented the Confederate sample (42%) while cartes were the prevalent format characterizing northern portrait photography (83%). This result is in keeping with previous observations (see Summer 2022, page 4, for details).

Photographic evidence of single-breasted uniform coats with left hand buttons, presumably made in small quantities, may reflect that manufacturers anticipated a need, or more probably, that their owners requested them be made as private purchase items.

Several published examples of uniform coats, conforming to the above criteria, were also identified; Echoes of Glory-Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy, shows examples of double-breasted (pages 102-103, 109, and 117) and single-breasted uniform coats, buttoned on the left (pages 119 and 137), as do Echoes of Glory—Arms and Equipment of the Union (page 100) and The Commanders of the Civil War (pages 68, 71, 122 and 191). The online collection of artifacts held in the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va., shows images of Maj. Alexander Hart’s (5th Louisiana Infantry) and Brig. Gen. Nathan G. Evans’ double-breasted coats, both buttoned on the left side (objects 0985.05.00068 and 0985.10.00109, respectively).

Surviving examples of Civil War-era double-breasted uniform coats, held in museum collections, which are buttoned on the left side present obvious limitations. Rather than reflecting the wearer’s preference, their presentations might represent the bias of the museum curator. In some cases, buttoning on the left might have been necessitated by the fact that buttons originally sewn to the right side of the coat were missing. Perhaps more instructive are those remaining examples of single-breasted coats buttoned on the left side.

Taken together, the photographic evidence and the presence of several museum examples confirm that double-breasted uniform coats were manufactured with two functional rows of buttons, and that single-breasted uniform coats were provided with buttons applied to the left side.

Closing thoughts

The total number of 102 photographs identified in this survey provided confirmatory evidence of one aspect of the material culture of Civil War-era uniform coats. Yet, this number represents a mere four-to-five percent of the more than 2,300 military-themed images published in Military Images since Winter 2014. The overwhelming practice of buttoning double-breasted uniform coats on the right obscures a significant manufacturing detail about these coats, that is, double rows of buttonholes, affording the wearer a choice to button their coat on the left. Though the number of soldiers and sailors who chose to fasten their uniform coats on the left certainly seems to have been in the minority, Evander Law was among those few who did so.

References: Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Army of the United States, June 1851, (reprinted in 1858 and 1861); Echoes of Glory-Arms and Equipment of the Confederacy; Echoes of Glory—Arms and Equipment of the Union; The Commanders of the Civil War.

Jack Hurov is a MI Copy Editor. He enjoys collecting and researching American military images.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.