By Adam Ochs Fleischer

This column is the first to investigate a backdrop used in Connecticut during the Civil War. Despite its small size, the “Nutmegger” state made a significant contribution to the war effort. More than 50,000 soldiers and sailors were raised in Connecticut between 1861 and 1865, constituting roughly 13 percent of its entire population at the time.

In addition to the manpower it provided, Connecticut was a manufacturing hub that produced vital supplies. Notably, Samuel Colt’s Fire Arms Manufacturing Company was located in the state’s capital, Hartford. One of the largest private arms manufacturers in the world, Colt’s produced hundreds of thousands of revolvers, rifles, and other firearms for the Union army. Colt’s factory and numerous other armories led to the popular sentiment shared amongst historians that Connecticut armed the Union.

The photographers

Just about a mile north of Colt’s factory, brothers Nelson Augustus Moore (1824-1902) and Roswell Allen Moore (1832-1907) operated a photo gallery. Described on the verso of wartime cartes de visite as located at the “Corner East of Allyn House,” their studio was steps away from the Hartford State House.

While little is known about Roswell, Nelson enjoyed a reputation as a well-regarded artist connected to the Hudson River School, whose landscape paintings typified the Romantic movement in American art during the mid-19th century. His work sought to capture the beauty of New England’s natural scenery, often featuring dramatic lighting and atmospheric effects. Many of Nelson’s paintings are held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and other eminent institutions.

Nelson established a daguerreotype studio with his brother in the early 1850s. The Moore brothers’ operation became known for producing high-quality portraits and architectural views in a variety of formats. Their expertise in both painting and photography allowed them to create images that were technically proficient and aesthetically impressive, bridging the gap between traditional art and the emerging medium of photography. By the Civil War, the Moore Brothers’ studio ranked among the finest in Connecticut, making it a popular choice for soldiers heading off to war.

Records indicate that, in 1864, Nelson left the photography business, handing over the studio to Roswell. This transition must have occurred soon after the brothers published The Last Men of the Revolution, a book that featured original albumen photograph portraits of surviving veterans of the Revolutionary War with narrative by Rev. Elias B. Hilliard. These portraits are the best-known work of the duo and remain historically significant.

Regarding Nelson’s departure from the studio, one source notes “despite the interesting and sometimes famous sitters that graced his studio…Moore longed to resume his painting full-time.” Nelson’s biography, detailed in a county commemorative record published in 1901, makes no mention whatsoever of the decade he spent as a photographer. That the biography was no doubt written by the subject suggests his foray into photography was a necessary diversion, a commercial enterprise, rather than a passion. At the very least, it indicates that it was not the legacy for which he wished to be remembered. Despite the apparent ambivalence Nelson felt towards his photographic work near the end of his life, the Moore brothers’ impact on Connecticut’s visual history is unquestionable.

The Backdrop

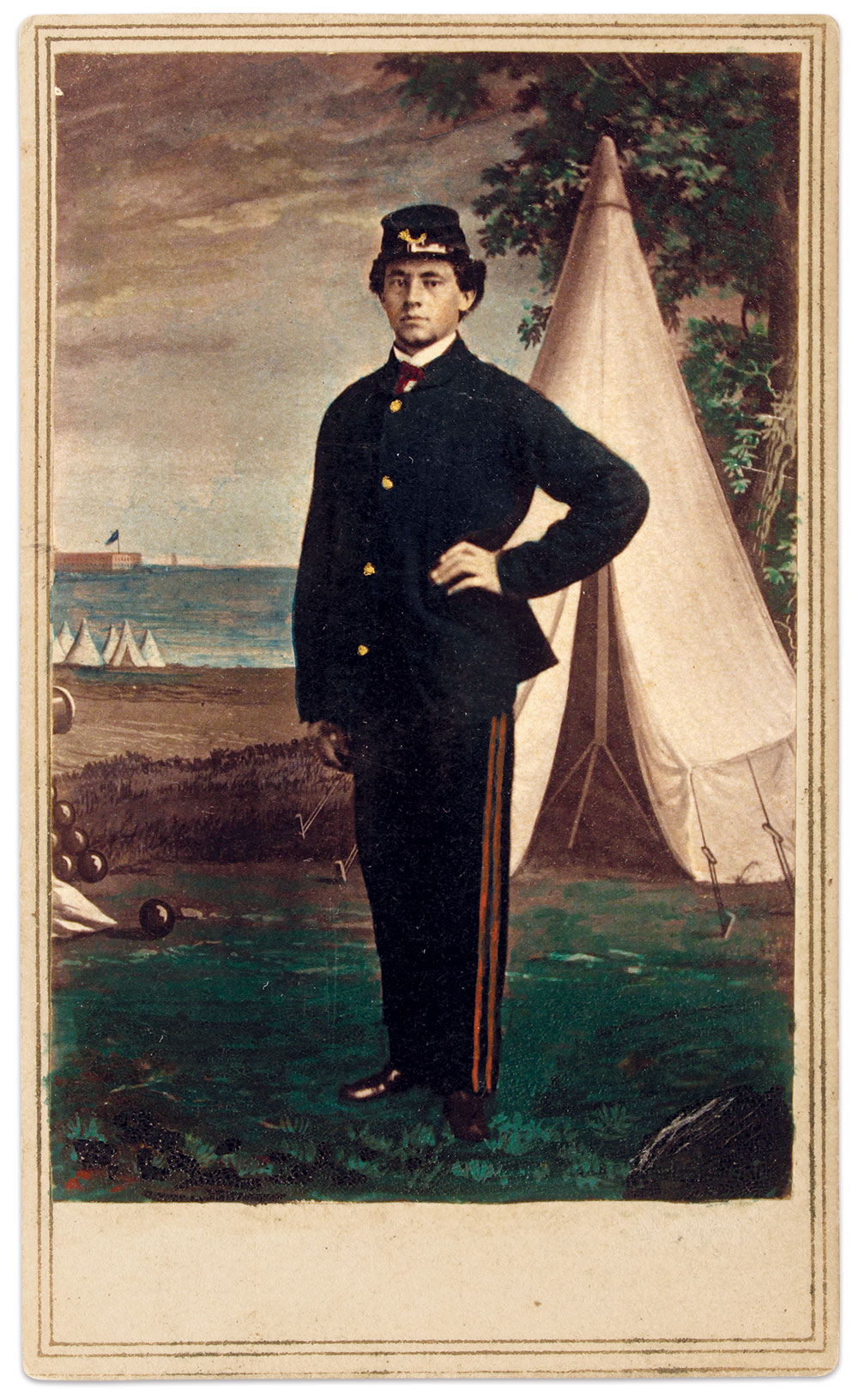

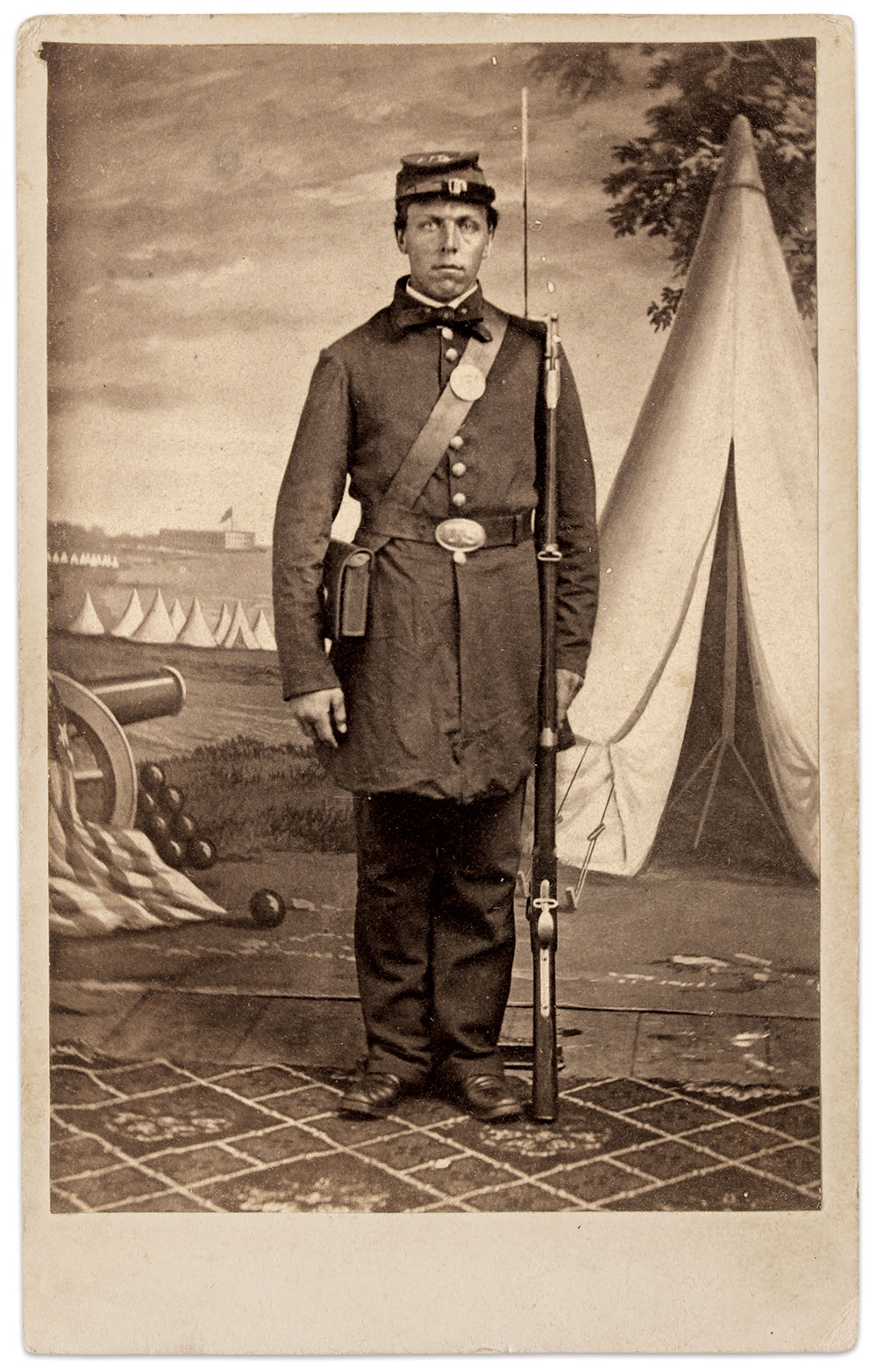

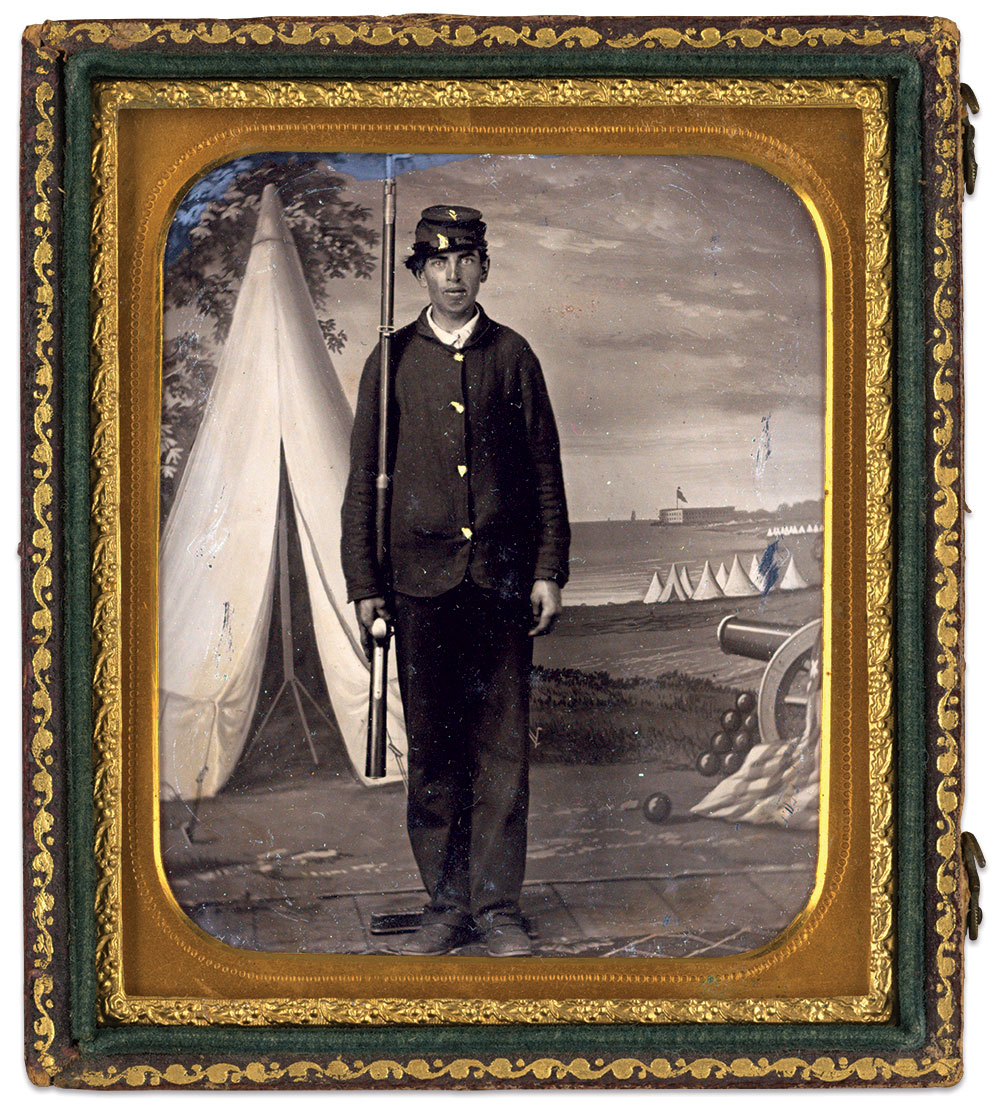

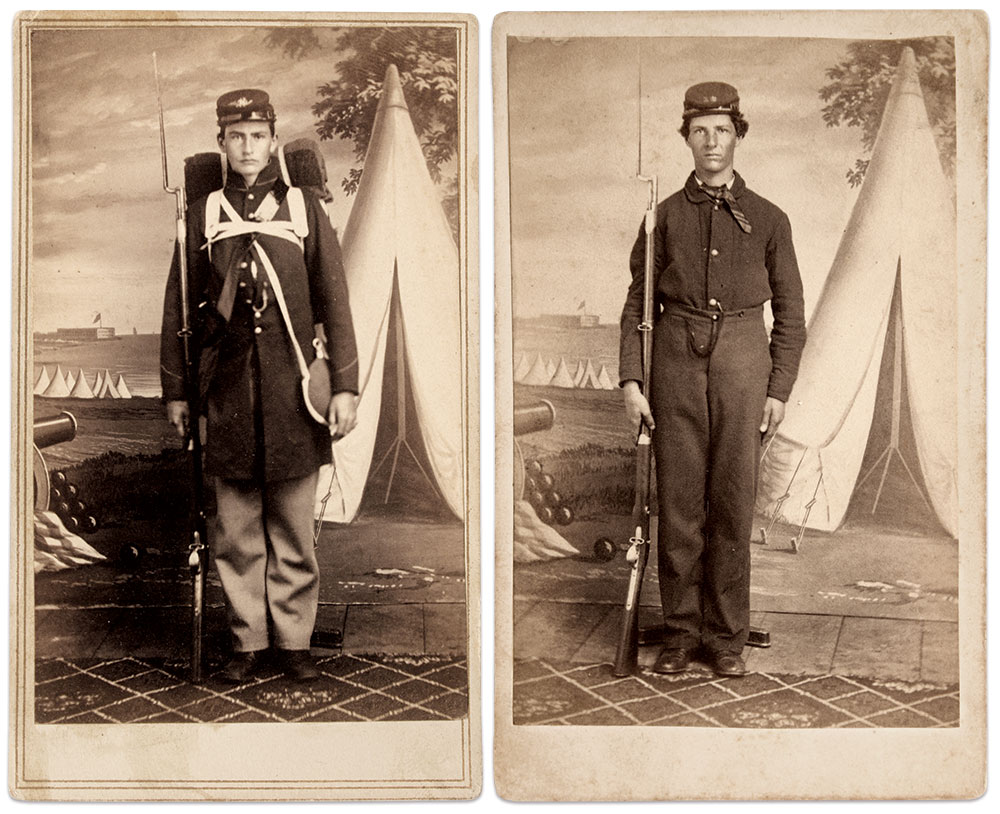

The Moore brothers’ military backdrop has been noted in both the tintype and carte de visite formats. At least one surviving carte has been heavily colorized. It is possible that Nelson colorized portraits himself.

An examination of the backdrop finds on one side a cannon with a stack of ammunition. In the distance is an encampment of Sibley tents, and further still, a fort with an American flag. Opposite the cannon is a tent with trees behind it. The sky is cloudy and atmospheric; perhaps the only hint of a shared aesthetic with some of Nelson’s landscape paintings.

Special thanks to MI Senior Editors Kurt Luther for flagging this distinctive backdrop, and to Buck Zaidel for sharing images and information.

Adam Ochs Fleischer is a passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.