By Kurt Luther

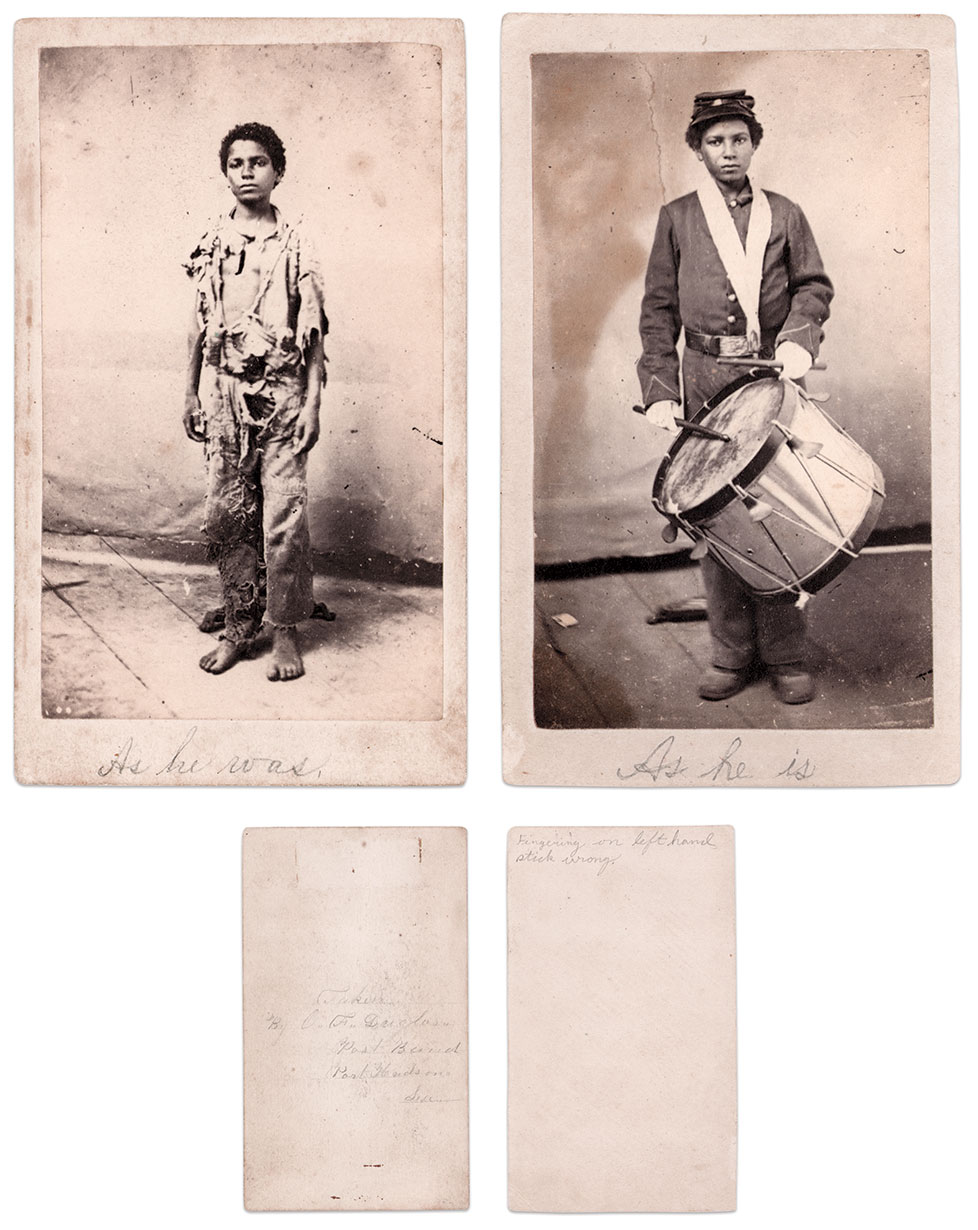

The pair of cartes de visite of a young African American boy transformed from a runaway slave into a Union drummer boy are among the most memorable images in Civil War photography. The two photos have appeared in countless books and scholarly articles in recent years, and were featured in Ken Burns’ 1990 documentary The Civil War.

Despite his prominence, the name and biography of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) drummer boy remain shrouded in mystery. In the Spring 2021 issue of MI, Natalie Robinson and I sought to shed some light on his identity by researching several publicly available copies of the photos across the collections of the Library of Congress, National Archives, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Louisiana State University, and Yale University, as well as the private collections of Ross Kelbaugh and Terry O’Leary.

We found the evidence contradictory. Period inscriptions alternatively name the boy “Jackson” or “Taylor.” Some sources place him in the 78th U.S. Colored Infantry, others in the 79th. Most support the loose narrative that the young man escaped slavery by entering Union lines or fortifications, probably near Port Hudson, La., and subsequently enlisted as a drummer boy. Some sources go so far as to name his master (“Col. Hamilton”), the distance he traveled (“600 Miles through swamp and cane brake”), or the time elapsed between photos (“two weeks later”). Surprisingly, we couldn’t find any references to his story in newspapers or other period publications.

A careful review of USCT service records uncovered dozens of Jacksons and Taylors in the 78th and 79th regiments, but only one musician, 14-year-old Hamilton Taylor. However, we couldn’t confirm him as the drummer boy in the famous photo pair, nor rule out the possibility that it depicts a fictionalized story for recruiting or political purposes, rather than a real person. We held out hope that additional research would finally solve the mystery. But several years passed, and the trail went cold.

Fast-forwarding to a few months ago, I was sitting in my office when I received a message from fellow MI Senior Editor Kevin Canberg, who was cataloging consigned items for Fleischer’s Auctions, where he is Director of Historic Photography. Among the various lots, he came across a previously unknown pair of the USCT drummer boy photos. Immediately, he knew he had seen something extraordinary written on the back of one of them. “I am trying to contain myself here but this seems important!”

All known copies of the drummer boy photos had blank backs. Some have period inscriptions referencing the boy’s slave-to-soldier narrative or offering personal commentary. But none had a photographer’s backmark or any clues as to the photographer’s name or location.

Yet, the faded period inscription pencilled on the back of one photo clearly read, “Taken By,” followed by two initials, the first ambiguous and the second looking like a capital “F,” and the surname, “Douglas.” On the next line, we recognized “Post” and another, unclear, word, followed by “Port Hudson, La.” If we could decipher the full inscription, we would learn the identity of the photographer behind these famous images.

Until now, “All known copies of the drummer boy photos had blank backs. Some have period inscriptions referencing the boy’s slave-to-soldier narrative or offering personal commentary. But none had a photographer’s backmark or any clues as to the photographer’s name or location.”

I squinted at the initials before “Douglas.” The first letter had a round shape and looked like a capital “O,” followed by “F.” Having two initials and a last name, and the overall combination looking somewhat uncommon, I thought I’d try searching it on Find a Grave. There were 34 matching records for “O.F. Douglas,” but only a handful who were alive during the Civil War.

One profile, Oscar F. Douglas, immediately caught my eye because the thumbnail image was a military headstone application card that a contributor had uploaded. I clicked the link and saw that the user had conveniently pasted in his service record as well. There were two entries. The first noted that Douglas served as a musician in the 4th Rhode Island Infantry. He was a Civil War soldier! More intriguing, he was a musician just like the mystery drummer boy.

My heart leaped when I read the second entry: “United States Corps D’Afrique Brigade Band #2.” Douglas apparently also served in the band of the Corps D’Afrique, a predominantly Black brigade formed from a core of the Louisiana Native Guard that played an important role in the Siege of Port Hudson.

Thus, Douglas, our leading candidate for the photographer of the mystery drummer boy believed to have served in Port Hudson, was himself a musician in a USCT band in Port Hudson. I shared my theory with Canberg, who had also been studying the inscription. He determined that the other unclear phrase was “Post Band,” meaning the photographer served in the band assigned to the military post at Port Hudson.

To confirm the identity, I wanted to find some connection between Douglas and photography. Opening Newspapers.com, I searched his name in U.S. newspapers. On the first page of results, an advertisement in the Sept. 4, 1871, issue of the Fall River (Mass.) Daily Evening News noted that Douglas was opening a new photographic studio in that town. We had our man. But who was he, and what circumstances led him to photograph the drummer boy? Eager to learn more, I continued my research.

Oscar F. Douglas (occasionally spelled “Douglass”) was born on Jan. 14, 1844, in Massachusetts, to parents Thomas Gray Douglas and Jane (Waldron) Douglas. He was the oldest of at least five children. By 1861, he was living in Fall River and working as a “photographer” making “daguerreotypes,” according to two city directories published that year. How he fell into that profession is unclear. His father, who died two years later in a railroad accident, last gave his occupation as a ship’s carpenter. Yet, Oscar and three of his four brothers–Charles, Walter, and William–would pursue photography as a career.

When the Civil War broke out, Douglas was only 17 years old. Yet, he was compelled to enlist, joining the 4th Rhode Island Infantry as a musician in October 1861, a couple months after its organization. One clue to his motivations may be that the 4th was famous for its band. The regimental history posted on the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) notes, “A fine band was enlisted by Joseph C. Greene, the veteran leader of the American Brass Band of Providence.” The American Band, which still exists today, was one of the most famous brass bands in the country during the Civil War. According to the band’s website, some of its members participated in the First Battle of Bull Run as stretcher bearers, but the “only casualty was the loss of its bass drum during the Union retreat.” It’s possible that Douglas was a fan (or even a member) of The American Band and that influenced his decision to join them in the Army.

In October 1862, weeks after his regiment suffered over a hundred casualties at Antietam, Douglas mustered out of the Army after a year’s service. Two months later, on December 5, he married Maria Brightman in Fall River. But less than a year later, Douglas would leave Maria at home and rejoin the Army. His decision was influenced by a man named Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore.

Gilmore, an Irish immigrant to Boston, became the most famous bandmaster of his time and is now considered the “father of the American concert band.” In 1861, Gilmore and his band joined the 24th Massachusetts Infantry and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s North Carolina Expedition. While Gilmore’s band was considered one of the best in the country, many other regimental bands were considered “ornamental” at best, and “monstrosities” at worst. In July 1862, Congress abolished all Union regimental bands. Gen. George B. McClellan required regimental bandsmen to be transferred to the much smaller number of available slots in brigade bands, reassigned as privates, or discharged. Both Oscar Douglas and Patrick Gilmore, along with his band, headed home around this time.

However, in 1863, Massachusetts Governor Andrews commissioned Gilmore as Chief Musician of that state, “with authority to enlist musicians for the service,” according to his New York Times obituary. The Songwriters Hall of Fame notes that “Gilmore would train, equip and send out 20 bands from Massachusetts.” Then, Andrews’ gubernatorial predecessor, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, appointed Gilmore as Bandmaster-General in charge of all musical organizations in the Department of Gulf. Gilmore began recruiting musicians in New England, some with prior Civil War service, and sending them south to Louisiana.

One of the military units requiring bandsmen was the Corps d’Afrique. Although the Corps d’Afrique was composed primarily of African Americans soldiers, Banks had sought to replace its Black officers, who had retained their commissions from their service in New Orleans’ Louisiana Native Guard, with White ones. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that White men were also recruited for the brigade bands, known as Brigade Band Number 1 and Number 2.

For example, an 1891 history of Westborough, Mass., names six residents who “enlisted in the Brigade Band, Corps d’Afrique, which served in Louisiana until the close of the war.” In another account, Capt. Lucian A. Cook of Leominster, Mass., after commanding Company A, 15th Massachusetts Infantry, and surviving Libby Prison, joined Corps d’Afrique Brigade Band Number 1. According to a genealogy book, “It being his wish to do such military duty as lay in his power, he enlisted in a band organized by P.S. Gilmore for service in the Gulf States, Nov. 23, 1863.”

Oscar F. Douglas joined Brigade Number 2 as a musician, third class, in November 1863. Few details of his service are available, and no history of the Corps d’Afrique bands exists in Frederick H. Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion or elsewhere. The Corps d’Afrique was based in Port Hudson since the Confederate surrender in mid-1863. Muster rolls in the National Archives, available in a digitized form via Fold3.com, indicate that he spent March or April 1865 in Baton Rouge, and the summer of that year in New Orleans, where he mustered out in August.

Anecdotally, there is evidence that the brigade bands were in demand throughout the Department of the Gulf. In The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War (1995), James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. notes that troops in Port Hudson largely had to entertain themselves. He recounts one incident in 1864 when “[a] musical band that had been assembled in Boston especially for the Corps d’Afrique was waylaid in New Orleans,” eliciting colorful complaints from both the Corps’ commander, Col. Samuel Miller Quincy, and an embedded New York Tribune reporter. A photographer captured the moment when the band finally made it to Port Hudson; it’s not impossible to imagine Douglas among the circle of uniformed musicians performing for Quincy’s staff, if not behind the camera.

In the spring of 1864, the War Department reorganized the regiments of the Corps d’Afrique into a standardized numbering scheme. For example, the 1st Corps d’Afrique Infantry was redesignated the 73rd U.S. Colored Infantry. Ostensibly, the Corps d’Afrique Brigade Bands Number 1 and 2 became the USCT Brigade Bands 1 and 2.

However, the evidence suggests a more complicated story. A historical marker in Hagerstown, Md., describes how the Robert Moxley Band, a group of African American musicians composed mostly of local enslaved people, was recruited by an army official as a unit to serve together as USCT Brigade Band Number 1, serving in Petersburg and eventually mustering out in Brownsville, Texas. Similarly, in digitized pension records posted on the National Archives website, a Black soldier, Sgt. James R. Ray, describes being transferred from the 32nd USCI to USCT Brigade Band Number 2, which was initially stationed at Camp William Penn in Philadelphia, Pa., and later moved to City Point, Va., and eventually Brownsville. A transcribed document posted on the University of Virginia Library’s website, dated July 31, 1864, signed by members of the USCT Brigade Band Number 2, acknowledges receipt of clothing and equipment at Camp William Penn, the premier training camp for African American soldiers during the Civil War. (Photo sleuths may also recall it as the site of the photograph that served as the basis for a famous USCT recruiting poster, as detailed in the Autumn 2015 edition of this column.)

Furthermore, using Gopher Records’ improved search interface, I found that the National Park Service’s Soldiers and Sailors Database shows entirely different rosters for these units. The members of Corps d’Afrique Brigade Band Numbers 1 and 2, including Douglas and Cook, are White, whereas those of the USCT Brigade Bands, including Moxley and Ray, are Black.

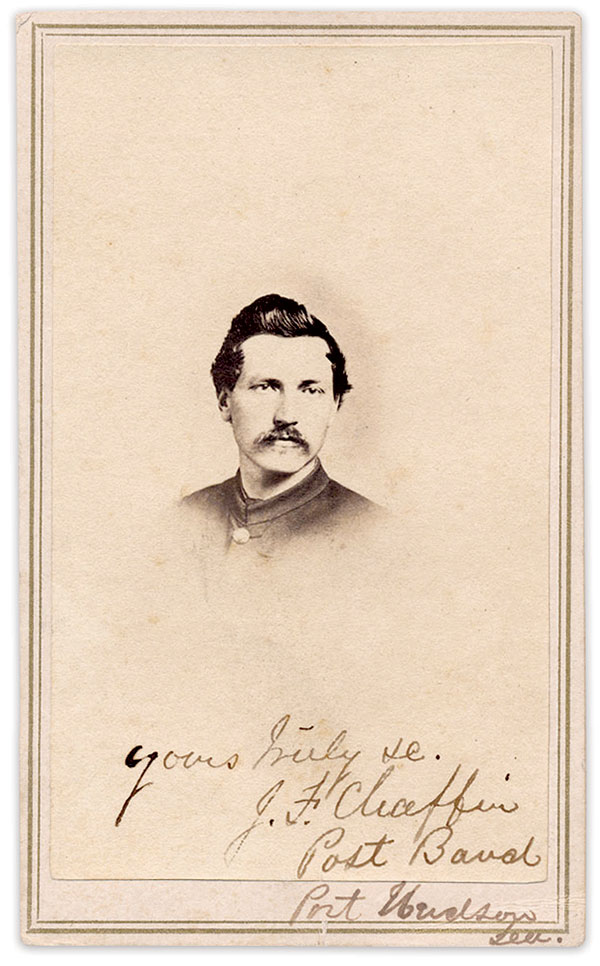

What, then, became of the Corps d’Afrique Brigade Bands composed of White musicians? I theorize that they remained in Louisiana as the “Port Hudson Post Band.” Oscar Douglas’s inscription on the drummer boy photo uses this nomenclature. A carte de visite sold by The Horse Soldier Fine Military Antiques, depicting a wartime portrait of Joseph F. Chaffin, who (like Lucian Cook) hailed from Leominster and (like Joseph Chaffin) served in Burnside’s Expedition before joining Corps d’Afrique Brigade Band Number 1, signed his name identically: “Post Band / Port Hudson, La.”

A third example comes from an article in the July 1, 1864, edition of The New Orleans Daily True Delta, which reports that the “Port Hudson Post Band” led by John Laflin had traveled to that city to perform in Jackson Square for Independence Day festivities. Laflin, one of the “Westborough six” and leader of Corps d’Afrique Brigade Band Number 1, is also notable as one of two White officers appearing on the same placard as the drummer boy portraits in the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center’s MOLLUS-Mass collection.

This brings us full circle back to Douglas’s life story. After mustering out of the Port Hudson Post Band in August 1865, he returned home to Fall River. Within a couple of months, he had set up a photography studio in Providence, co-founded with his bandmate (and another of the “Westborough six”), Francis Sandra, according to the local newspaper.

Unfortunately, the partnership seems not to have flourished. Five years later, Sandra had moved back to Westborough, where he would work as a farmer, miller, and house painter. Douglas, still living in Fall River with Maria and now a young daughter, Clara, remained committed to photography. As mentioned earlier, in 1871, he opened his new studio closer to home; his newspaper ad promised a spacious facility “furnished with a large and skillfully constructed sky-light” and “admirably arranged for the production of first class work.”

Douglas worked out of this studio for over a decade. One of two photographs taken by Douglas in The George Eastman Museum collections–an albumen portrait of Olive Ann Caldwell, wife of fellow Fall River photographer Warren H. Caldwell–dates from this period. However, his business may have been struggling because, in April 1883, a newspaper report noted that “E.F. Davis has purchased all negatives from Oscar F. Douglas’ gallery.” (Davis would later open a Fall River studio with Oscar’s younger brother, William.) A couple weeks later, Douglas’s wife, Maria, died at age 37. A single father of four children, he quickly remarried to Elizabeth Estes in October that year, and they had two more children together.

Douglas, Elizabeth, and their large family spent the next three decades in Fall River, interrupted only by a short interlude to Albuquerque, N.M., in 1885, where Douglas’s brother, Thomas Jr. lived. Thomas, the only brother not to go into photography, followed in Douglas’s footsteps in another way by joining the Union Army, enlisting in Company F, 15th U.S. Infantry, and fighting in the Western Theater. After the war, he became a lawyer, working in Mississippi, Washington, D.C. and eventually New Mexico. He died in 1889 in a Soldiers’ Home in Maine.

Douglas worked as a photographer into his mid-60s. He stayed in touch with fellow Civil War veterans, including serving as commander of the Grand Army of the Republic’s Richard Borden Post No. 46. In 1920, he attended a reunion of the 4th Rhode Island Infantry in Providence, where he was acknowledged as the last survivor of Greene’s American Band, according to the Fall River Evening Herald. Douglas died on March 1, 1924, age 80, and was buried in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery.

Douglas’s biography does not allow us to definitively identify of the mystery drummer boy. However, it sheds new light on the circumstances in which the photo was taken, including a confirmation of the location (Port Hudson) and photographer, as well as the broader context of the Corps d’Afrique, military bandsmen, and USCT musicians. It’s not yet clear precisely what led Douglas to take the photos, but as a photographer and Corps d’Afrique bandsman, he was ideally suited to the task at hand. A New Englander, he may have aligned with the abolitionist message of the photos, or he may simply have seized the opportunity to hone his craft. Either way, Douglas produced two of the most iconic images of the Civil War. While photo sleuths continue to discover new insights about these portraits, they still have more to tell us.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Oscar F. Douglas: The Photographer Behind the Iconic USCT Drummer Boy”

Comments are closed.