By Paul Russinoff and Jim Quinlan, with images from the Elizabeth Traynor Collection

A few days after the fall of Fort Sumter, Cadet Edward Willoughby “Will” Anderson stood before his classmates, faculty and administrators at West Point. He placed his hand on a Bible and listened as a magistrate recited the Oath of Allegiance to the United States government.

When the moment came to kiss the good book and seal the sacred pact, he couldn’t do it.

This ended his cadetship and his future in the U.S. Army.

Few cadets could have made a stronger claim to a West Point berth than Will. He hailed from a military family that traced its roots to the nation’s early days.

His grandfather, Col. William Anderson, served in the Marine Corps in the War of 1812 as a lieutenant, under hero Stephen Decatur, followed by Commandant of Virginia’s Norfolk Naval Yard. In 1811, then Lt. Anderson married Jane Willoughby, daughter of one of the founding families of Norfolk. She gave birth to a son, James Willoughby Anderson, the first of three children. James was Cadet Will’s father.

James entered West Point in 1829, graduated in 1833, and began his army career as a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry. His service took him to Maine, Michigan and far south to Florida for the Seminole War, where he received a captain’s brevet for gallantry.

While stationed there, he met and married Ellen Maria Brown, a New Hampshire native staying with a well-to-do uncle. In 1841 at St. Augustine, Jane and James brought Will into the world. Two sisters, Georgia and Villette, followed.

Like many military families, the Andersons moved about frequently. First to Buffalo, N.Y., and then to Newport, Ky., making do with limited resources provided by the antebellum army.

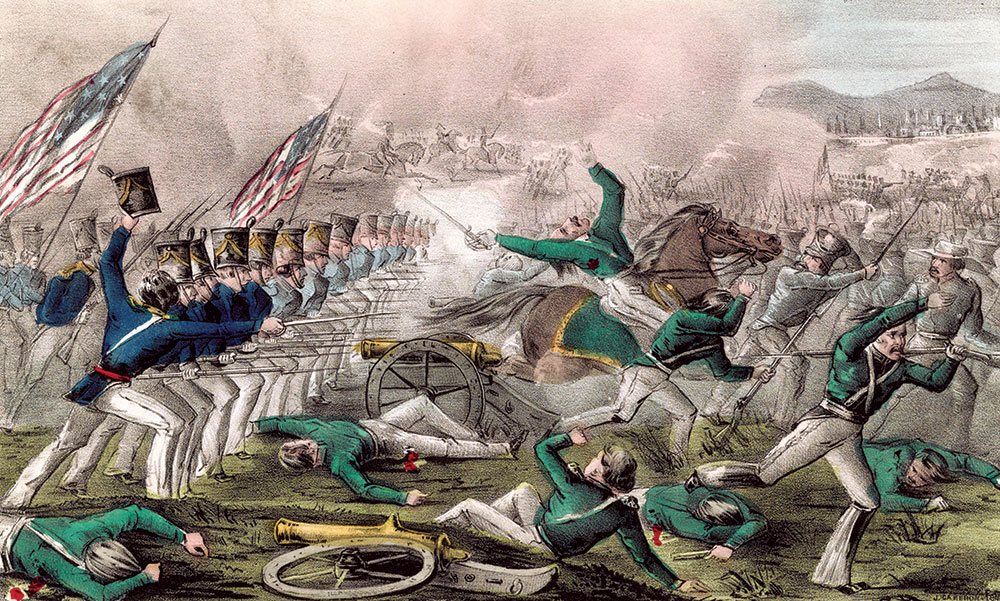

When the Mexican War began, now 35-year-old James received a captain’s commission and left with the 2nd Infantry for the front. The regiment joined Col. David E. Twiggs’ Brigade and participated in significant operations.

Son of a war casualty

Meanwhile, Ellen and her children, including six-year-old Will, stayed with family in Florida. Following the Battle of Churubusco on Aug. 20, 1847, Ellen received a letter containing dreadful intelligence. Her husband was not coming home. James’s West Point classmate Henry W. Wessels, a future Union army brigadier general, broke the news of his mortal wounding at Churubusco and death. Wessels wrote, “If this mournful event has wrung tears of sorrow from me, how must it be with the Orphans? … He was struck by a musket ball in the neck, the ball itself resting against the spine, producing paralysis of the left side, though free from pain and perfectly sensible. He was taken to the Church of Churubusco that evening and on the 22nd moved to the Officers Hospital… at that time the surgeons gave me some encouraging words, but he lived only till about 10 o’clock.”

Now widowed, Ellen remained in Florida with her sister and brother-in law until 1850, when she moved with her three small charges and her sister, first to Georgia, and then Connecticut, before settling in New York City in 1851. Despite economic challenges, she was able to provide for herself and her children through a combination of a military pension, her own efforts (including penning a novella under a pseudonym) and regular contributions from her brothers and brother-in-law.

In 1857, 17-year-old Will enrolled in the New York Free Academy, a precursor to the City University of New York (CUNY). Will excelled academically for the next two years and was listed on the merit roll in 1859 as fourth in the sophomore class. Given his family’s economic circumstances, the subsidized education West Point offered would be more than welcome. His recommendation to West Point came from Mexican War hero Winfield Scott.

Scott noted, “I beg to ask a cadet’s warrant for Master Edward Willoughby Anderson, son of Major J.W. Anderson, an excellent officer of the 2nd Infantry who, after distinguishing himself on several occasions in the Mexican War was mortally wounded at the Battle of Churubusco. Master Anderson, now eighteen years of age, was born in the Army in St. Augustine, Florida and is now a student at the High School of this city. He is in robust health, active and intelligent. His father’s merits, coming in support of his own, seem to give him the highest claim to the warrant.”

Appointed at large to the Academy, Will began his life as a cadet in 1860.

Will’s West Point correspondence to his mother and relatives were published in the American Historical Review in 1928, opening an important window into the mindset and emotions of a family with Southern and Northern roots. As clouds of war gathered over the nation, Will’s letters reflected an exuberant young man with a sense of humor adjusting to the routines, requirements and hazing which are part and parcel of the plebe year. One memorable event Will documented was the campus visit by the Prince of Wales in October 1860, “Gentlemanly enough looking, though not so manly, as I had at first thought.”

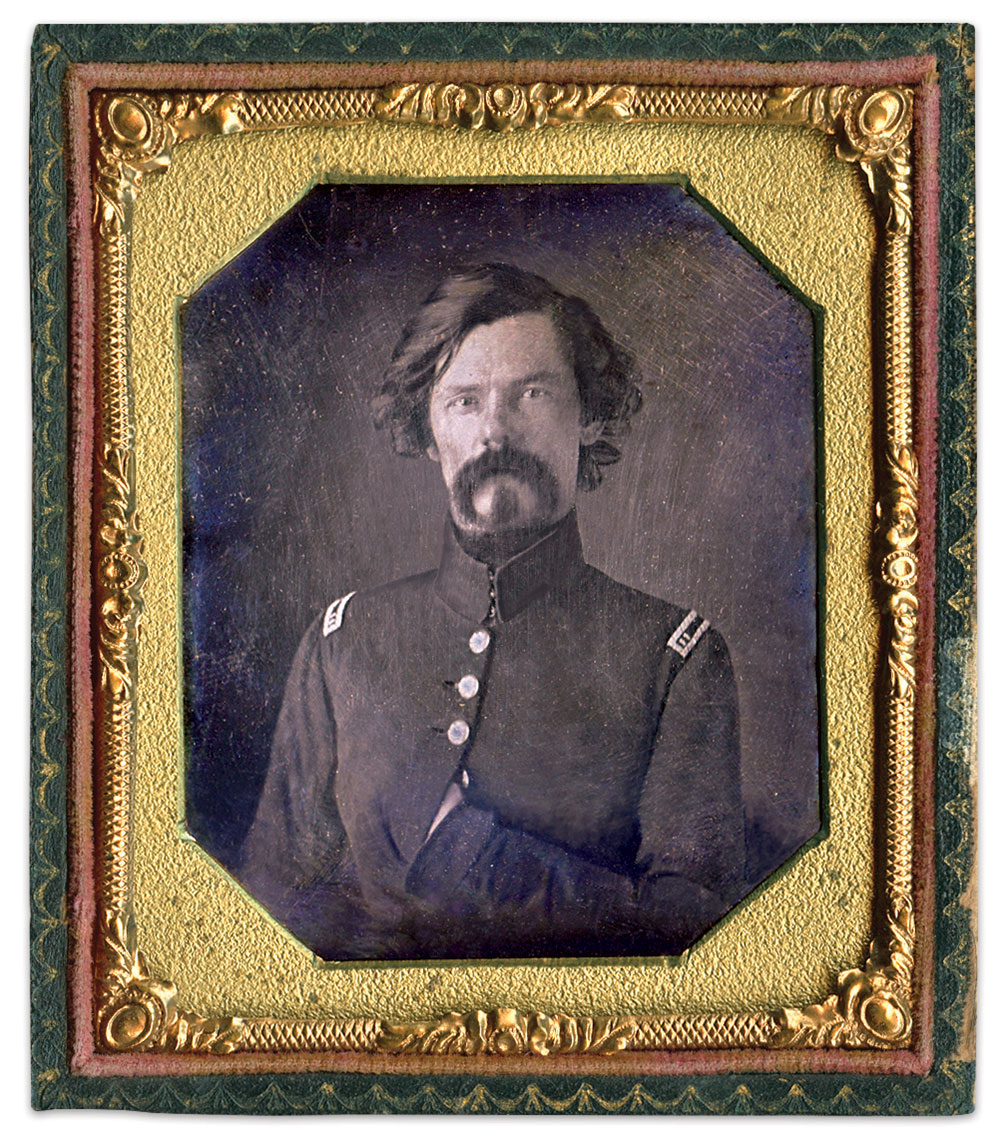

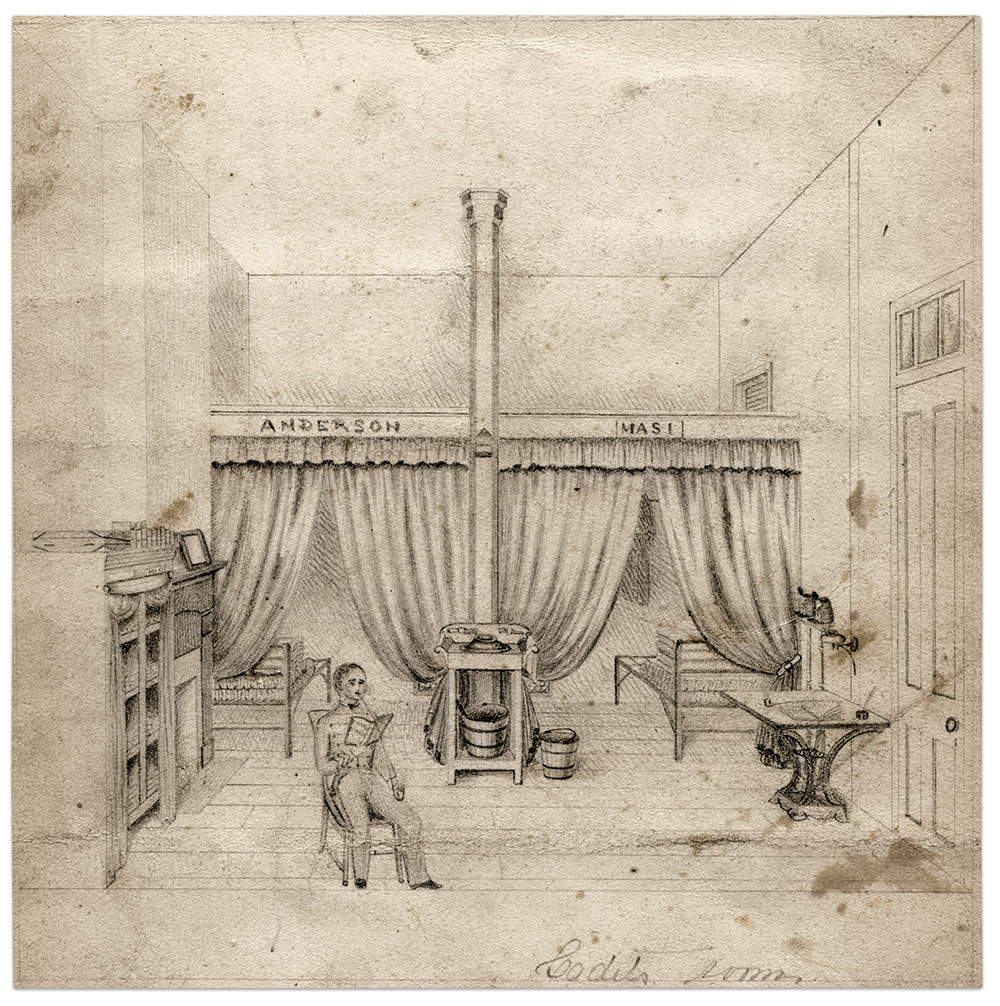

Initially quartered in a tent with other plebes including George Gordon Meade’s son and namesake, Will later moved into the barracks and roomed with Francis John “Frank” Masi, a cadet from Norfolk, Va., where the Anderson family held ties through Will’s grandparents.

As 1860 drew to a close, Ellen visited and wrote letters to her son that reflected strong southern sentiments, but speculated that the impending hostilities may ultimately blow over. But by the end of December, after the secession of South Carolina, her letters took on a more serious character and a discussion of how and when Will may be compelled to leave. “You are not exactly commissioned officers yet. You are under a sort of contract to serve the U.S. eight years, and you are under this bond as minors. Now I think you are bound by that contract, but of course no contract ever contemplated that a man should fight his own countrymen.”

By March 1861, she suggested that Will should consider military schools in the South, “but still it is above all things desirable to graduate at West Point, if possible. No other school in the world has such a reputation. No other school in the world gives its graduates such a status.”

Choosing sides

On April 12, 1861, the U.S. army garrison of Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor came under attack by Palmetto State forces in open rebellion against the federal government. That same day in West Point, Will wrote his mother. “I wish this fuss between N and S was stopped.”

A few days later, a nervous West Point administration tested the loyalty of the Corps of Cadets by administering a new oath. Will, standing second academically in his class, and his brother cadets had to choose sides.

Will explained what happened to his mother:

“Dear Mama, I have refused to take the oath,” Will wrote, adding, “Cadet [Henry Algernon] Dupont of the 1st Class from Delaware but appointed at large, has been my friend whilst I have been here. His father was a classmate of Pa’s, he advised me to take the oath. I actually cried before I went over there, so you can conceive how I was bothered mentally. I know well that I resign everything, prospects in life, etc. by my action, and that for a little while I will have to increase your expenses.”

Will continued, “I went up and placed my hand on the Bible, I would have taken a conditional oath, I kept my hand in the Bible till the Magistrate got through the totally unconditional oath, and required us to kiss the Book, I couldn’t do it. It was a solemn occasion for me. All my class were in the Chapel. Many of the other classes were there to see the ceremony… if they will let me resign, I will do it.”

Will became the first cadet to refuse the oath and resign. Nine more in his class followed him, including his roommate, Frank. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported, “The 5th class was called upon to swear allegiance to Lincoln’s Government—Out of ten Southerners, nine refused to take the oath. They are threatened with having their names ignominiously struck from the roll. They will rather consider it an honor to have their names erased for not swearing allegiance to a power hostile to their every interest. In a week there will not be a cadet here from the South.”

The Richmond Enquirer added, “They all propose to enter the military service and have the high ambition to render the most effective aid in the struggle for Southern Independence.” The list was headed by John Pelham and Tom Rosser from the 1st Class down to the 5th Class, which included Will and Frank.

Will volunteered in the Provisional Army of Virginia and received an appointment as a second lieutenant. On May 31, 1861, he requested duty at Norfolk, Va. The army approved his request and assigned him as the 6th Virginia Infantry’s Drill Master.

A few weeks later, on June 24, Will wrote to his mother from Norfolk’s Entrenchment Camp. Describing the location as miserable due to the oppressive heat and mosquitoes, he regarded his duties as rough as the recruits had a hard time remembering “their hay foot from the straw foot.”

The transition of the Provisional Army of Virginia to regular service in the Confederate States Army impacted Will’s rank and assignment. Appointed a cadet and given command of a pioneer company in the Corps of Engineers in September 1861, he and his men constructed batteries along the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad.

His real world experience with raw recruits and building gun emplacements, combined with his West Point education, served him well as the war unfolded.

From the Peninsula through Appomattox

Will had his first taste of action in the field during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. Assigned as an engineer and aide on the staff of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger (West Point 1825), Will participated in the Seven Days Battles and suffered undisclosed injuries at Gaines’ Mill that took him out of action for about two months. In his after-action report, Huger praised Will and other staff for rendering important service.

While Will recuperated, he received an appointment as captain of ordnance with the Provisional Army of the Confederate States on Aug. 14, 1862. His mother never learned about Will’s promotion as she had succumbed to breast cancer a week earlier at age 48.

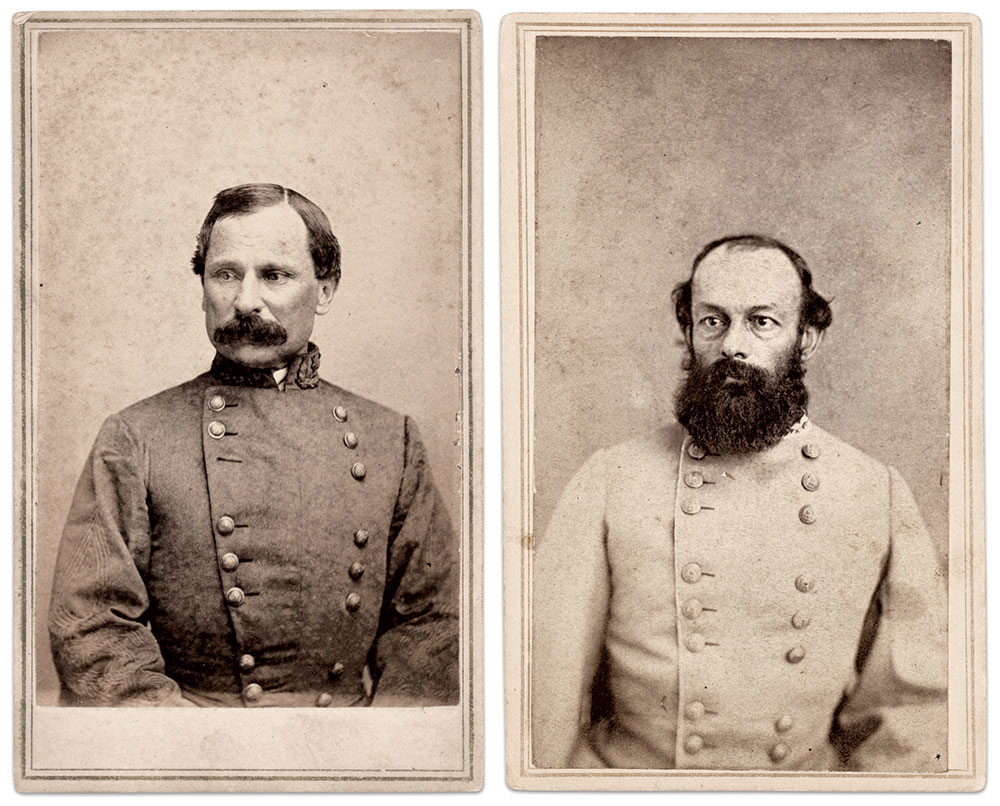

Will spent the rest of the war reporting to three officers: Col. Edward Porter Alexander, Chief of Ordnance of the Department of Northern Virginia, and two generals commanding divisions in the 3rd Corps: William Dorsey Pender and Cadmus M. Wilcox. He served on Wilcox’s staff at Appomattox.

According to his biography in Confederate Military History, Will went to great lengths to avoid surrender. He made his way to Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army in North Carolina after Lee’s surrender. After Johnston surrendered forces under this command, Will joined Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton’s remaining troops, and then left for Texas to join up with Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith. After Smith’s surrender, Will surfaced in New Orleans and later returned to Virginia and civilian life. There is no record that he signed the Oath of Allegiance.

Postwar years

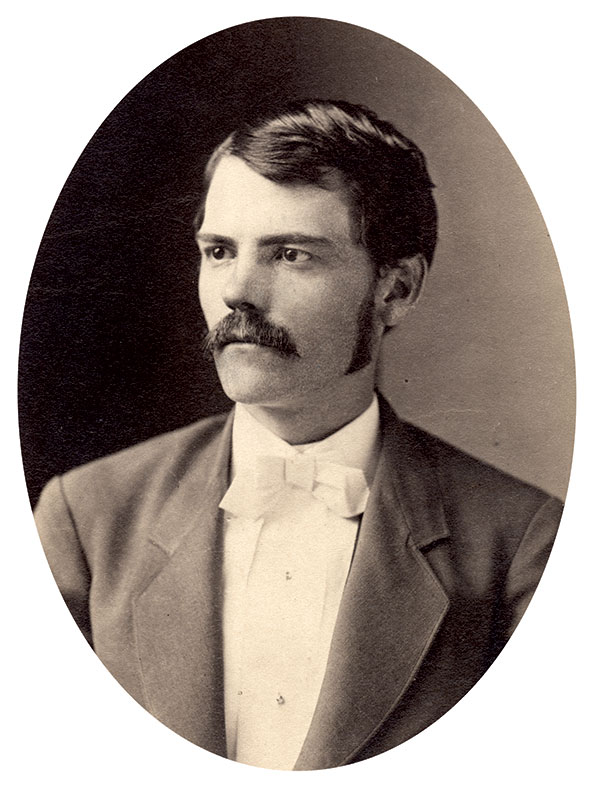

In 1867, Will married Elizabeth Felicia Masi “Lizzie” Masi, the sister of his West Point roommate Frank, in Norfolk. They raised six children, two of whom would join Will in his patent law practice in Washington, D.C., along with Frank Masi himself.

Perhaps not surprisingly considering his refusal to surrender, Will became a prominent member of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV). As Lieutenant Commander of UCV Camp No. 1191 in the nation’s capital, Will strived to ensure the services and sacrifices of the Confederate soldier did not become one of history’s forgotten memories.

Perhaps not surprisingly considering his refusal to surrender, Will became a prominent member of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV). As Lieutenant Commander of UCV Camp No. 1191 in the nation’s capital, Will strived to ensure the services and sacrifices of the Confederate soldier did not become one of history’s forgotten memories.

One of the efforts of the UCV and other organizations and individuals was realized in 1900. On June 6, Congress appropriated funds to remove Confederate remains buried within the District of Columbia and Northern Virginia and reinter them in the new Confederate section at Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1903, Will, in his official capacity with the UCV, wrote to Dr. Samuel Lewis, Chairman of the organization’s Monument Committee. Will proposed that each former Confederate state establish a means to officially recognize their soldiers.

Will stated that “monuments are erected over our great leaders, showing the reverence, in which we hold their memory, and while such monuments may be in questionable taste—in God’s Acre—there can be no doubt of the warm feeling and true spirit of those who place them in position. And monuments are erected to the Confederate soldier as a class, and all these public memorials not only point to our heroic dead, but also indicate in a mystic way the hope, the wish, the determination, it may be, that the great sacrifice offered upon the altar of their country shall not pass out of mind and be forever forgotten.”

Will also championed a proposal to establish an annual memorial day, on the Sunday immediately succeeding the third day of June, the birthday of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. For Will, Confederate Memorial Day would be held at Arlington National Cemetery.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and other veteran groups submitted a petition to erect a fitting monument to honor the Confederate soldier. In 1906, U.S. Secretary of War William Howard Taft approved it. Moses Ezekiel, a renowned sculptor, Virginia Military Institute graduate and Confederate veteran, was commissioned to design and build what would be called the Arlington Confederate Monument.

Six years later, now President Taft addressed the UDC at a convention in Washington. Thanking the women for the opportunity to address the convention, Taft stated, “You are not here to mourn or support a cause. You are here to celebrate and justly to celebrate, the heroism, the courage, and the sacrifice to the uttermost of your fathers and your brothers.” He added, “No son of the South and no son of the North, with any spark in him of pride of race, can fail to rejoice that common heritage of courage and glorious sacrifice that we have in the story of the Civil War and of both sides in the Civil War.”

Taft’s successor, Woodrow Wilson, dedicated the Arlington monument in June 1914 and proclaimed it an emblem of a reunited people.

Will lived to see his dreams of a Confederate section at Arlington realized. He died on Sept. 2, 1915, at his Washington home. He is buried in grave 80-A within the Confederate section, less than 50 yards from the grave of Moses Ezekiel at the foot of his sculpture.

More than a century later, in 2022, the Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense, known as the Naming Commission, formed to “remove the names, symbols, displays, monuments, and paraphernalia that honor or commemorate the Confederate States of America.” The Commission recommended removal of the Confederate Memorial, which was accomplished on Dec. 23, 2023. The monument is currently stored in a government facility in Virginia.

The graves of Will, Ezekiel, and other Confederates remain.

Acknowledgment: Sincere thanks to Elizabeth Traynor and Raymond Gill, scholars and custodians of their family genealogy. Their generous assistance and sharing of materials and images facilitated this article.

Paul Russinoff of Baltimore has been a passionate collector and researcher of photographs from the Civil War since elementary school. He has been a subscriber to MI since its inception. His profile of Maj. Benjamin F. Watson, “A Savior of the Capitol,” (MI, Spring 2021) received an Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award. Paul is a MI Senior Editor.

Jim Quinlan established and leads the Arlington National Cemetery Project to identify all Civil War veterans on the grounds. He is also the proprietor of The Excelsior Brigade, which provides fine Civil War memorabilia to collectors.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.