At Atlanta on the afternoon July 22, 1864, a massive assault by Maj. Gen. Frank Cheatham’s Confederate corps tore into the Union’s western front. The attack landed squarely on the 17th and 15th Corps. The day, already oppressively hot, soon reached the boiling point as officers and men, most having shed their coats and trappings in the heat, scrambled to meet the moment.

Gunsmoke from the rising din of musket fire and rhythmic thump of artillery shells obscured visibility. Union soldiers under fire in the trenches wondered from which direction the enemy had advanced. Rumors spread down one section of the line that the Confederates had taken nearby Bald Hill and that the bullets and shells shrieking around them came from their own men.

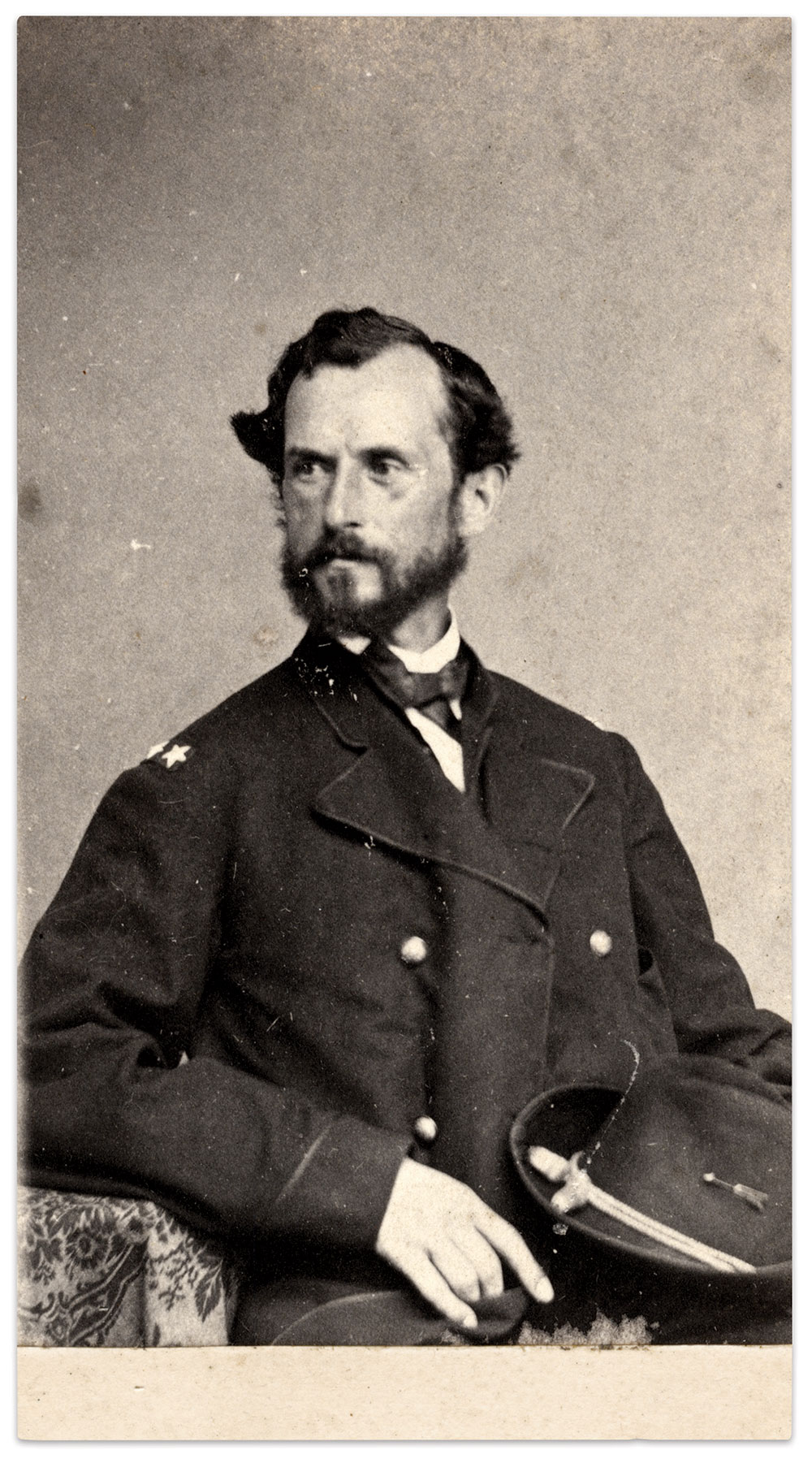

Long after the war, an artilleryman told a gathering of veterans the story that circulated among the boys in blue in the trenches. First Lieutenant Richard Stanley Tuthill (1841-1920) of the 1st Michigan Light Artillery explained to the audience that a beloved and much-admired senior officer, Brig. Gen. Manning Ferguson Force, called for a flag to make it clear that these were Union troops. A young subordinate, believing the situation hopeless, searched for a white handkerchief, towel or shirt for the general to wave in surrender. A furious Force barked, “Damn you, sir! I don’t want a flag of truce; I want the American flag!”

Tuthill continued, “A flag was soon obtained and planted upon the highest point in our earthworks, and there it remained. General Force himself was struck down by a minie-ball, which entered just at the lower outer corner of the eye, passed through his head, and came out near the base of the brain. The blood gushed from his eyes, nose, and mouth; but he uttered no moan, nor a word of complaint. The bones of his mouth were shattered, and he could not, in fact, speak. But from his eyes flashed a spirit unconquered and unconquerable, the spirit of a soldier sans peur et sans reproche.”

Tuthill reminded his listeners that the quiet and mild-mannered Force may not have actually spoken these words. But there could be no doubt of Force’s courage and gallantry, as evidenced by his receipt of the Medal of Honor in 1892 for Atlanta. The citation noted: “Brigadier General Force charged upon the enemy’s works, and after their capture defended his position against assaults of the enemy until he was severely wounded.”

Force’s face injures were not as severe as Tuthill believed. The general had returned to his command by October 1864, participated in the March to the Sea, and received a brevet promotion to major general for Atlanta. A Harvard-educated lawyer who had settled in Cincinnati prior to the war, Force went on to serve in the county’s judicial system. Appointed Commandant of the Ohio Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in 1888, he served until his death in 1889 at age 74.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.