By Cliff Krainik

In the early 1980s, my wife Michele and I owned and operated a gallery of vintage photographs in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. We specialized in 19th century photographs of noted personalities and offered cased images—daguerreotypes and ambrotypes—plus cartes de visite, stereoviews, large albumen prints of the Civil War by Brady, Barnard and Gardner, and views of Western Americana. We were ideally located adjacent to the Old Print Gallery, one of America’s foremost antique print dealers.

Across the street stood Booked Up, a bookstore owned by Pulitzer prize-winning author Larry McMurtry.

I remember that warm, spring afternoon when this elegantly dressed gentleman entered our gallery and asked if we might have an original photograph of his illustrious ancestor. That ancestor’s name, he confided, was Raphael Semmes.

I paused, perplexed for a moment, and sheepishly replied, “Who is Semmes?”

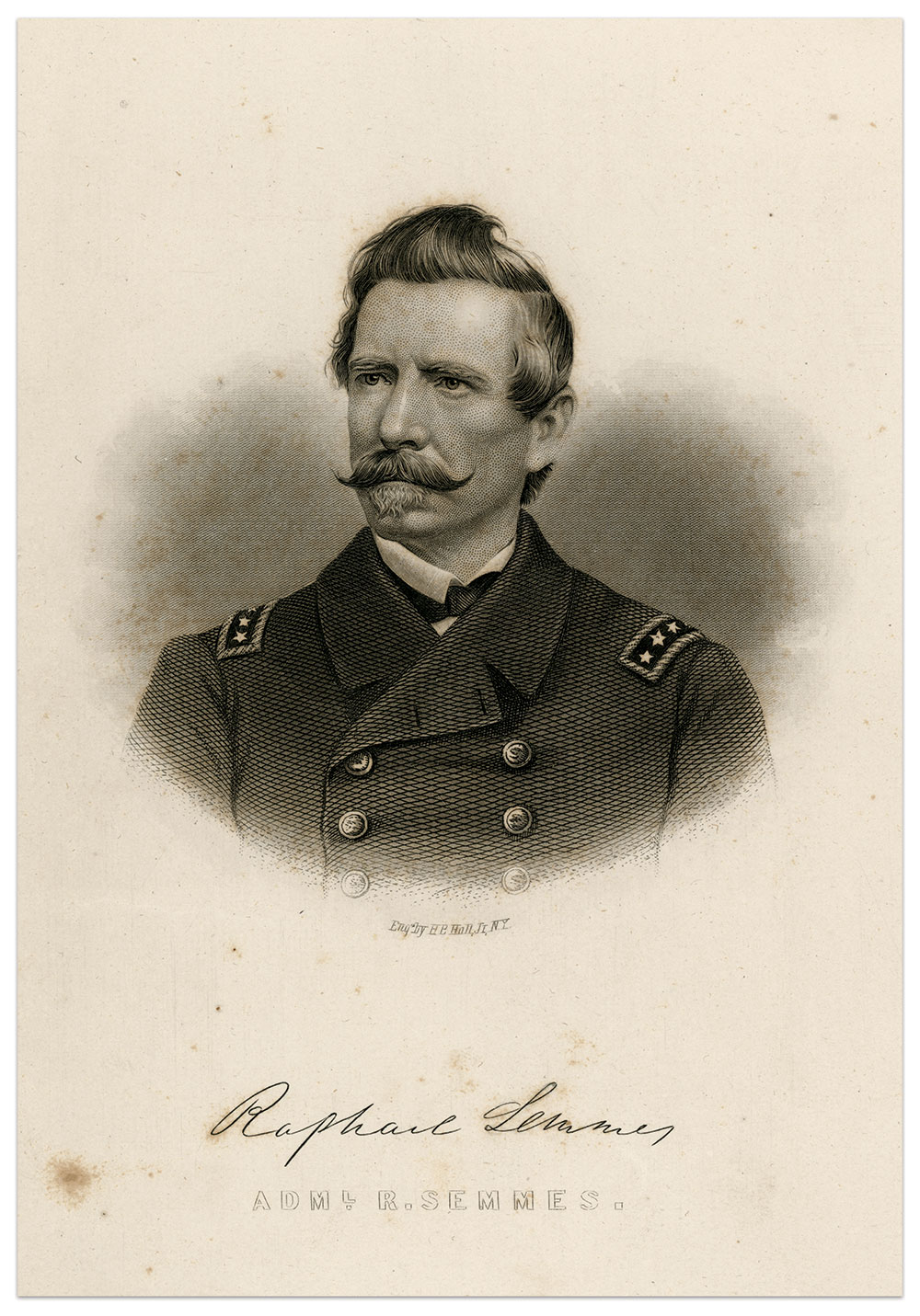

Taken aback by my obvious ignorance of naval history, he patiently explained that his relative grew up in Georgetown just a few blocks from my shop and that he practiced law, authored two bestselling books, was the only military officer to hold the rank of both rear admiral and brigadier general in the Confederate service, and is regarded as the greatest naval raider in the history of the world! He then handed me an engraved business card for his law firm, emblazoned with the name Semmes, and requested to be informed if I located a photograph of Semmes.

Raphael Semmes has been the subject of four in-depth biographies and dozens of articles. They reveal the complexities of his character: His devotion to Catholicism and the Confederacy, his innate aggressive nature, and his philosophical view of the natural wonders he encountered.

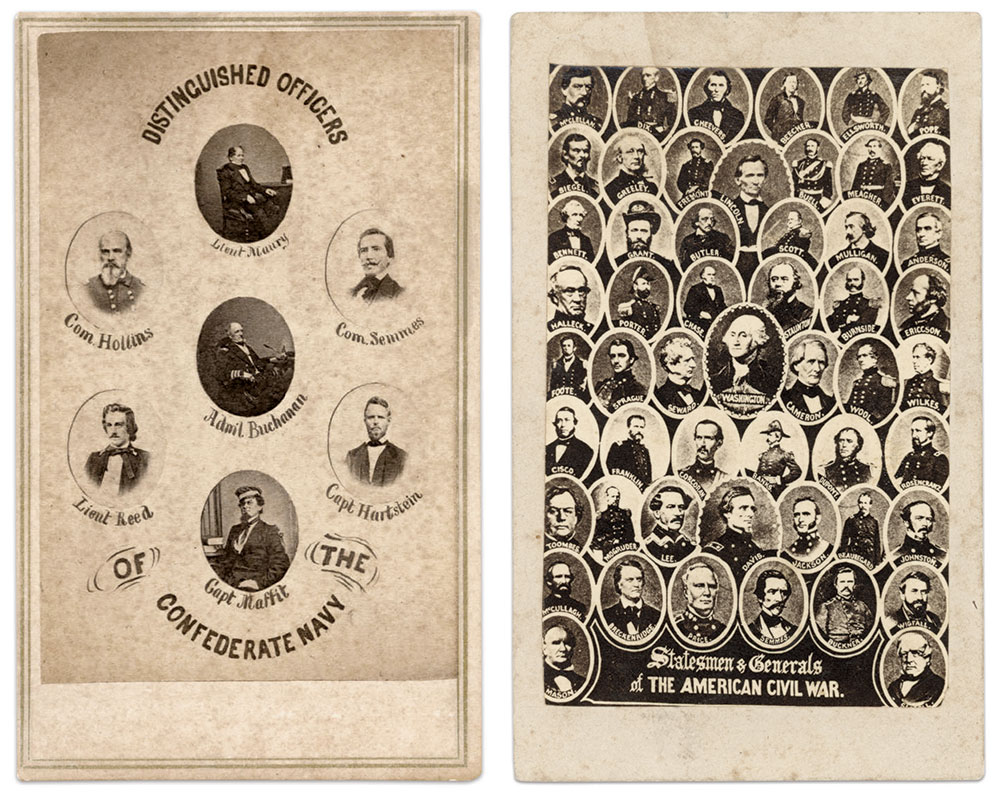

The exploits of his Confederate ships Sumter and Alabama have been told in many works. Because of the limited resources of the South to establish a navy, President Jefferson Davis and his Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory, directed then Capt. Semmes to outfit a steam cruiser, run the blockade, and wage economic war to destroy the enemy’s commercial shipping.

Semmes’ stature as a superb mariner with a thorough understanding of the legal limitations of his mission is well documented.

Between July 3, 1861, and April 27, 1864, Semmes steamed from the whaling grounds of the North Atlantic to the shipping lanes of the Caribbean, down the coast of South America, on to Africa, and then to Southeast Asia. In all, he is credited with capturing, sinking, or burning 82 U.S. commercial ships valued at more than $6 million ($146 million in today’s dollars). As a result he became the most successful commerce raider in maritime history.

In this worldwide theater, he faced significant logistical challenges with an ever-pressing need for food, fuel, munitions and repairs. He also had to contend with the delicate balance of discipline and the need to accommodate the base desires of a motley crew that held no allegiance to the Southern cause, while also trying to stay one step ahead of a fleet of Union warships staffed with well-armed captains and crews intent on bringing Semmes’ career to an abrupt end.

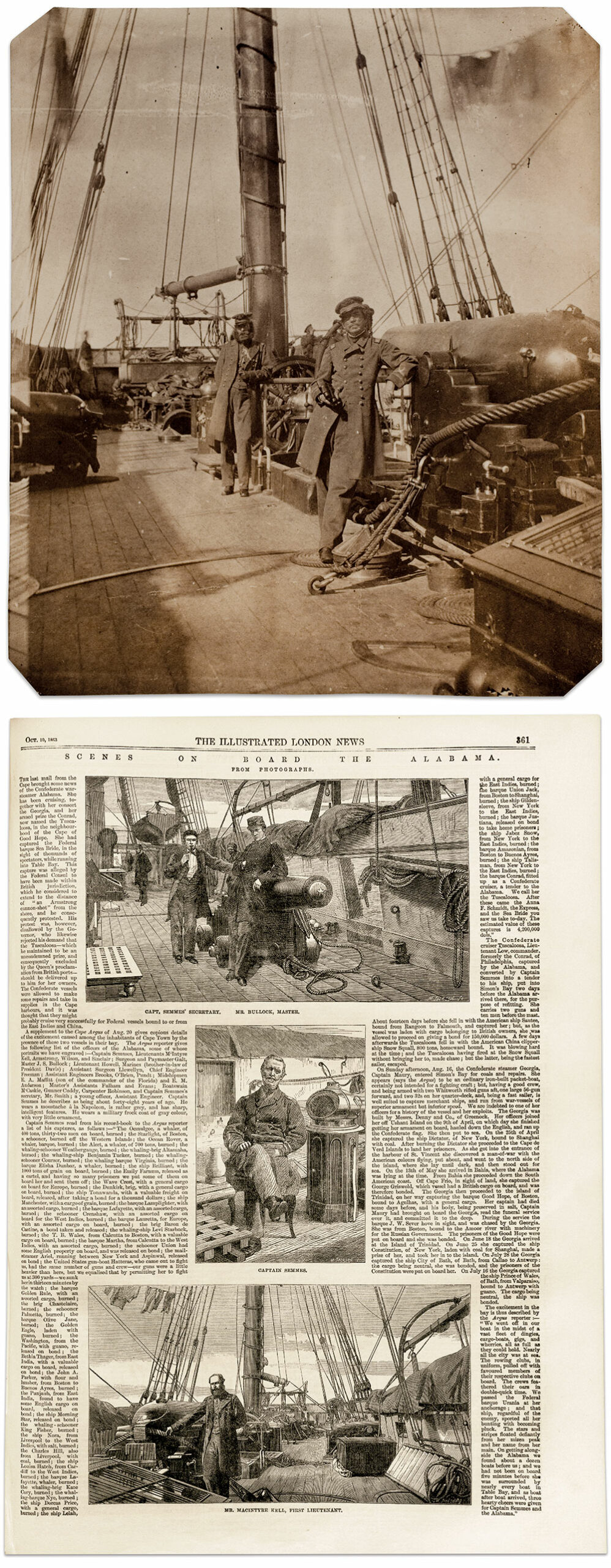

Semmes attributed his great success in devastating U.S. commerce to the element of surprise, the superb construction and design of the Alabama, and the ability and loyalty of his Southern officers, especially his first lieutenant, John McIntosh Kell (1823-1900).

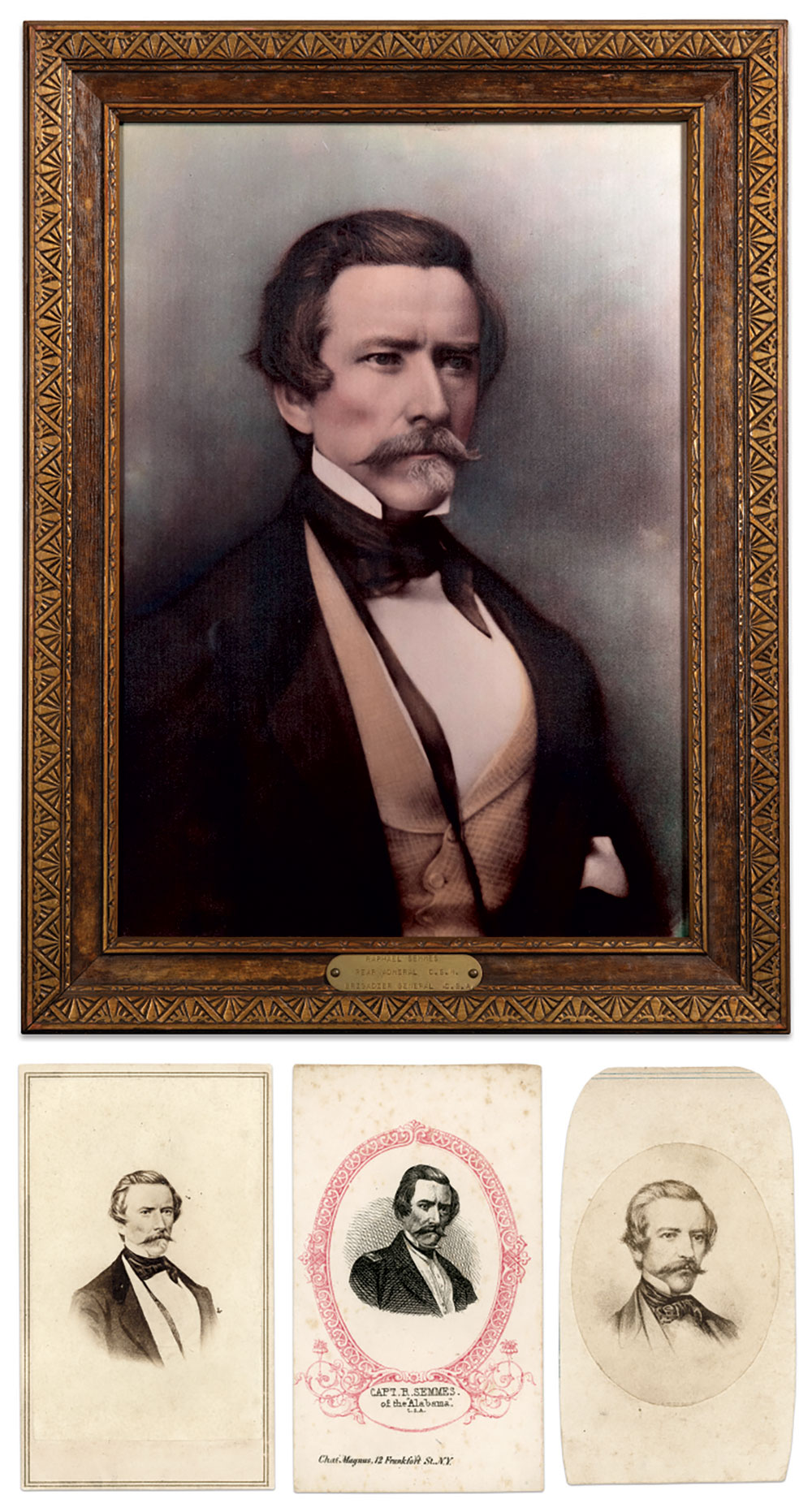

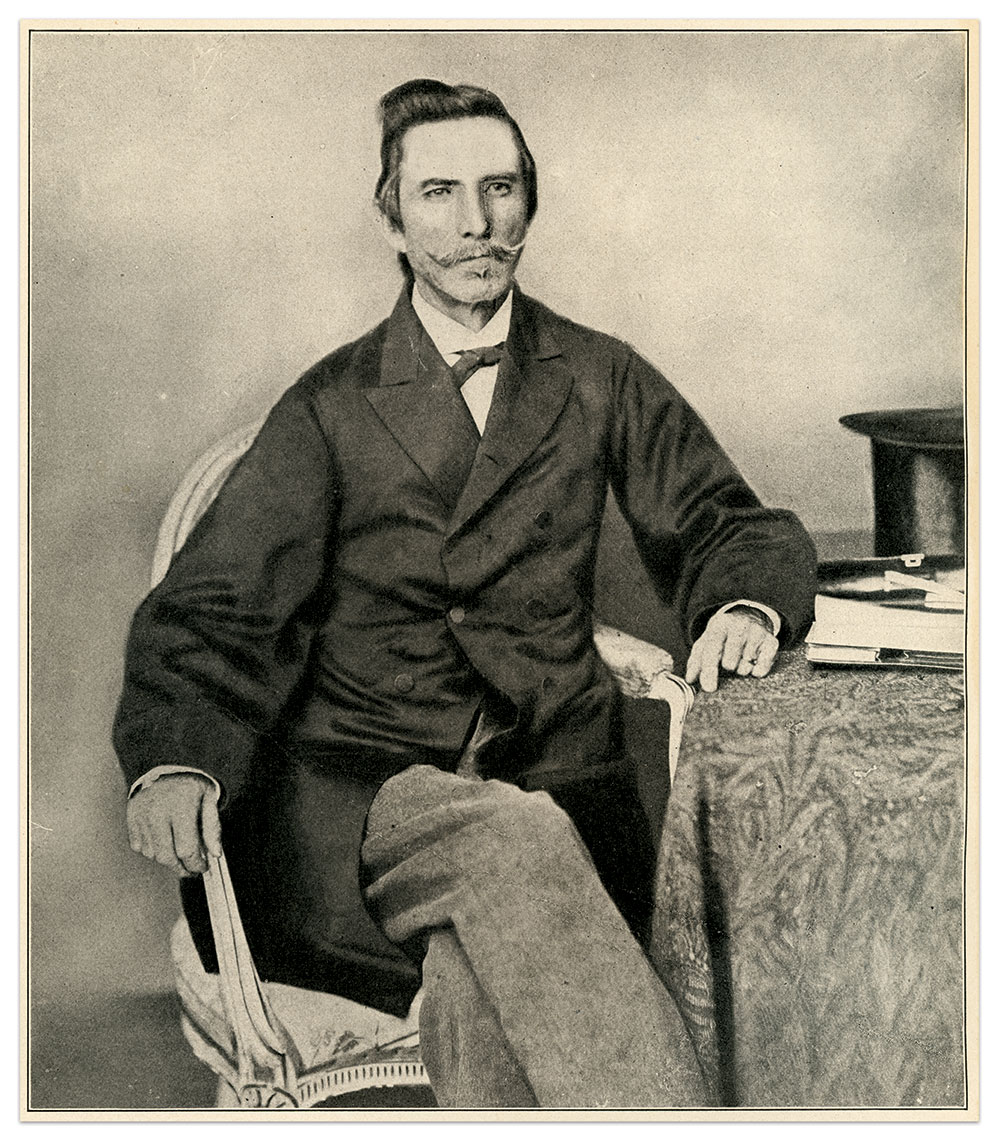

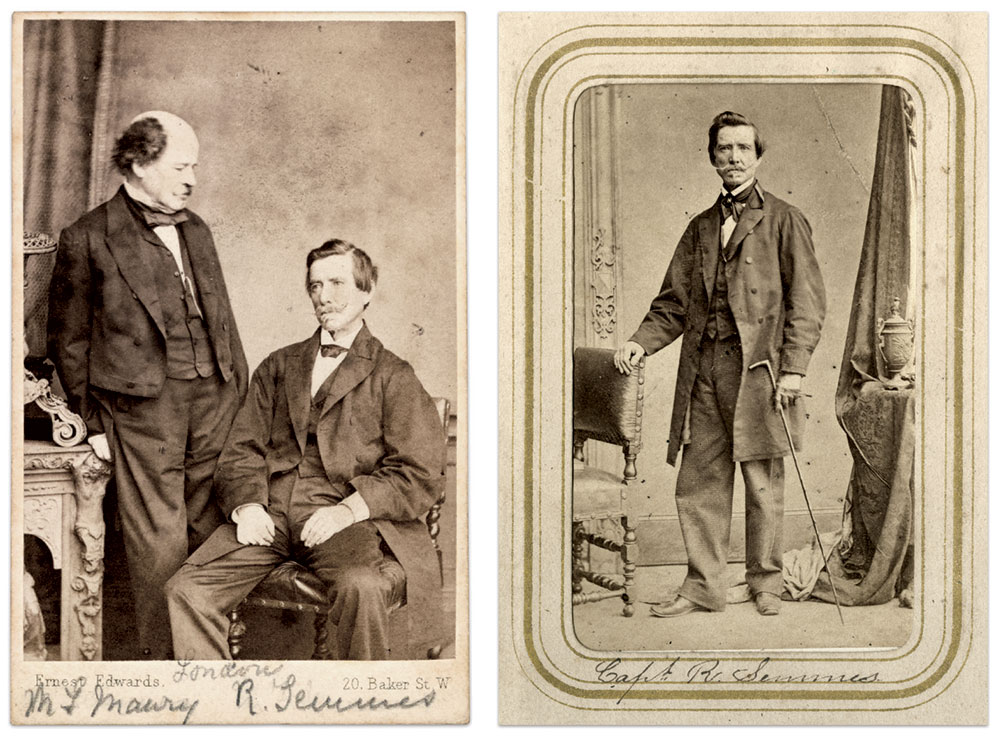

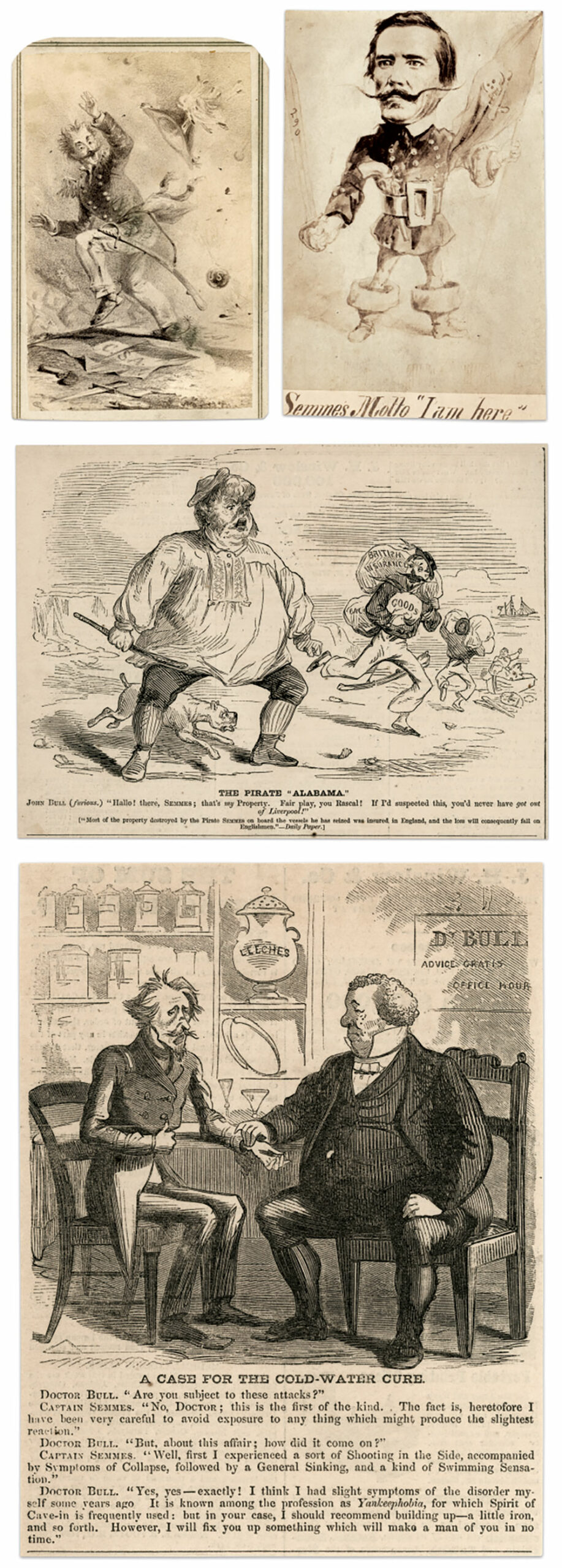

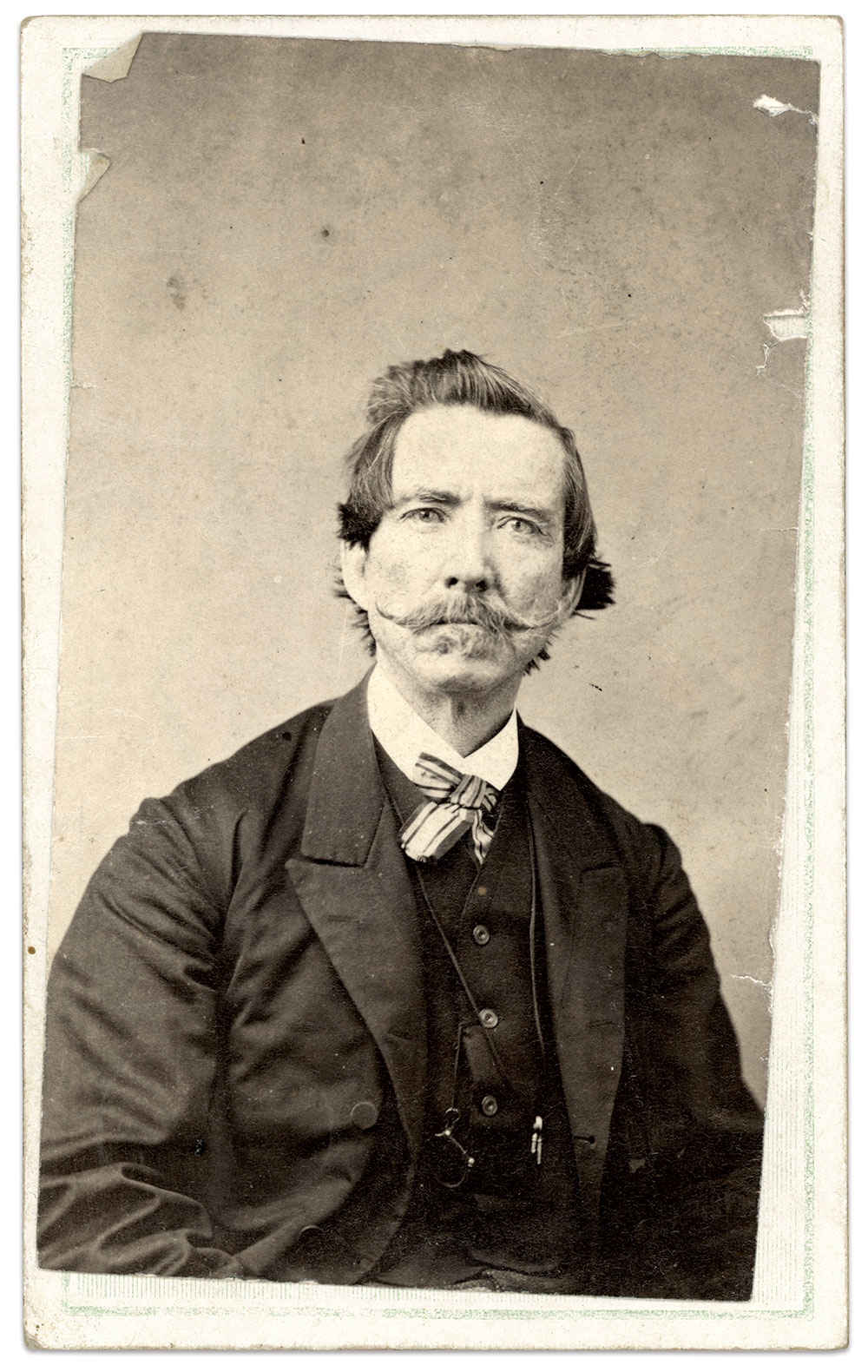

By all accounts, Semmes’ appearance did not match the vision inspired by his daring exploits. Many of his prisoners were sorely disappointed when coming face to face with the notorious “pirate.” Semmes was short and very slim, probably not weighing more than 130 pounds. His face was bronzed from years of exposure to sun and wind. His iron-gray hair was upswept from his broad forehead, as if in response to the ever-present salt spray of his voyages.

Two physical characteristics of Semmes, noticed by every acquaintance, were his penetrating gray, wolf-like eyes and his signature stylized 17th century Van Dyke mustache with ends that curled up into tips—reminiscent of a seagull in flight. Semmes, or his steward, carefully maintained its shape by applying beeswax, which earned him the endearing name “Old Beeswax” by his crew.

Though Semmes’ mustache has often been compared to those of King Victor Emanuel and Kaiser Wilhelm II, I contend that it inspired Walt Disney’s legendary pirate, Captain Hook.

Semmes was a courtly Southern gentleman, fastidious in his personal appearance, in uniform or out, as testified by his photographs. His refined manners served him well in cultured soirees, where he could discuss literature and savor musical interludes. He enjoyed the company of lovely women and could be sociable, even jovial, with friends. A pious Catholic, a product of his Maryland heritage, religion played an important part of his day, which started and ended with prayer.

In war, he was an aggressive, shrewd commander who, like his contemporary Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, did not waste words when business was at hand. Semmes was decisive, high strung and nervous. He was often seen in solitude, staring across the vast seascape, while twirling the ends of his mustache in deep contemplation.

Establishing his reputation as a warrior and author

Born Sept. 27, 1809, at Tayloes Neck, Nanjemoy, Charles County, Md., he was the fourth child of Richard and Catherine Middleton Semmes. Orphaned at an early age, he was raised by his namesake uncle in Georgetown. Young Semmes had the benefit of private tutors and attended Charlotte Hall Military Academy in Maryland. He showed an early interest in nautical matters and with the assistance of another uncle, Benedict Semmes, he secured a midshipman’s appointment in the U.S. Navy in 1826. He received a promotion to lieutenant in 1837, following tours in the Caribbean and Mediterranean.

Semmes also studied law and gained admission to the Maryland Bar in 1834. He practiced in Cincinnati during extended shore leave prior to the Mexican War, a time when the U.S. Navy had more prospective captains than ships. His legal education and experience would serve him well during the Civil War and through his life.

On one long leave, in Ohio in 1837, he married Anne Elizabeth Spencer and started a family that grew to include six children.

When the Mexican War began, Lt. Semmes commanded the brig Somers. His ship was part of the flotilla blockading the port of Veracruz in preparation for the massive assault on the city—the largest amphibious invasion prior to World War II.

In December 1846, a fierce squall capsized the Somers with the loss of 37 men. Semmes and nearly half his crew narrowly escaped drowning. A court of inquiry exonerated Semmes of any blame for the loss and commended him for his actions.

Semmes went on to be sent inland as an aide de camp to Maj. Gen. William J. Worth, and participated in the September 1847 Battle of Chapultepec, part of the Mexico City Campaign.

In November 1847, Semmes moved to Mobile, Ala., which he considered home for the rest of his life. During shore leave he practiced law and wrote a stirring account of his war experiences, Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War. Published in Cincinnati in 1851, the book satisfied Semmes’ literary ambitions and proved popular with the general public—a best seller in its day. Semmes’ navy duties during the 1850s included stints as a lighthouse inspector for the Gulf of Mexico region and secretary of the Lighthouse Board in Washington.

Feared captain of the raiders Sumter and Alabama

Semmes ranked as commander and served with the Lighthouse Board when his adopted state of Alabama seceded from the Union on Jan. 11, 1861. The provisional Confederate government offered him a commission, which he accepted. He resigned from the U.S. Navy in mid-February.

Before the outbreak of hostilities in Charleston Harbor, Semmes embarked on an unsuccessful covert mission to procure arms and ships from northern manufacturers.

When Semmes returned to the South, he received an appointment to head the Confederate Lighthouse Service; an honor he declined in favor of a naval combat command. Secretary of the Navy Mallory granted Semmes’ request and ordered him to New Orleans to convert a commercial steamer into the Sumter, the first Confederate commerce destroyer.

In June 1861, the Sumter penetrated the Union blockade at New Orleans. Thus began Semmes’ crusade in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea that resulted in the loss of 18 vessels over a six-month period. The rigors of the active campaign took a serious toll on the Sumter, which steamed into the neutral port of Gibraltar in early 1862. Deemed too damaged for repairs, Semmes and several officers received orders to report to the Azores to oversee the outfitting of a new vessel, the Alabama. Semmes also received a promotion to captain for his leadership. In August 1862, the sleek sloop-of-war with Semmes at its helm embarked on a new and even more successful reign of terror, taking out merchant vessels at an alarming rate.

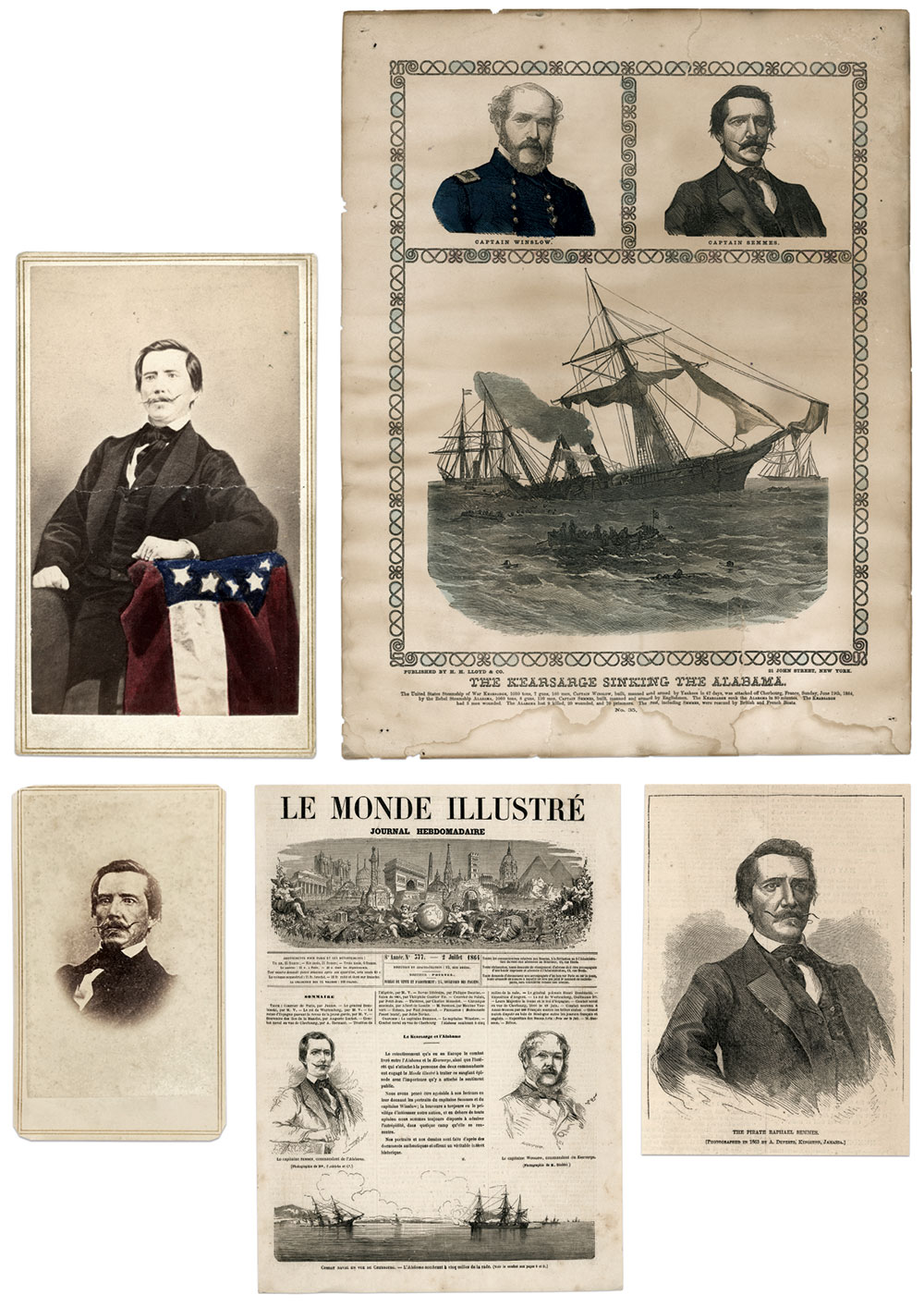

Meanwhile, U.S. shipping companies and their insurers were alarmed by staggering losses. Some ship owners elected to remain in safe ports or transfer titles to neutral countries. Others pleaded with the federal government to catch and destroy the Alabama and vented their frustrations in the press. Yankee newspapers and photographers launched the 19th century version of “fake news,” portraying Capt. Semmes’ legitimate actions of war as piracy. They furthered the fiction of “Semmes the Pirate” during and after the war.

Gerald C. Roxbury, USN Retired Collection, and an unidentified photographer, author’s collection. Engravings from the author’s collection.

According to international law, piracy takes place outside the normal jurisdiction of a state, without state authority, and is a private, not political, act of warfare. Semmes, a commissioned officer of the Confederacy, operated within the boundaries of international law. Even President Abraham Lincoln, with his well-versed legal mind, fed the propaganda apparatus when he described the Alabama as a pirate ship.

By the summer of 1863, the Alabama encountered fewer U.S. merchant ships. Semmes charted a course from the Brazilian coast for Cape Town, South Africa, to refuel and resupply. Arriving in early August to a hero’s welcome and fêted by officials, Semmes and his crew enjoyed the delights of shore leave in a foreign port.

Before long, the Alabama returned to sea and resumed wreaking havoc on U.S. commercial interests. Semmes’ seeming success came with a high cost to his health, to his storm-tossed ship, and to the morale and discipline of his mostly mercenary crew.

In mid-June 1864, the Alabama arrived at the French port of Cherbourg for much needed repairs and supplies. There, the raider was finally confronted by the Union sloop-of-war Kearsarge, commanded by Capt. John A. Winslow.

Semmes elected to engage the enemy in a confrontation set for Sunday morning, June 19, disregarding a directive by Confederate authorities not to battle enemy warships. Two decades after the battle, his first lieutenant, John McIntosh Kell, recalled a discussion he had with Semmes on the matter:

“I have sent for you to discuss the advisability of fighting the Kearsarge. As you know, the arrival of the Alabama at this port has been telegraphed to all parts of Europe. Within a few days, Cherbourg will be effectually blockaded by Yankee cruisers. It is uncertain whether or not we shall be permitted to repair the Alabama here, and in the meantime, the delay is not to our advantage. I think we may whip the Kearsarge, the two vessels being of wood and carrying about the same number of men and guns. Besides, Mr. Kell, although the Confederate states government has ordered me to avoid engagements with the enemy’s cruisers, I am tired of running from that dirty rag!”

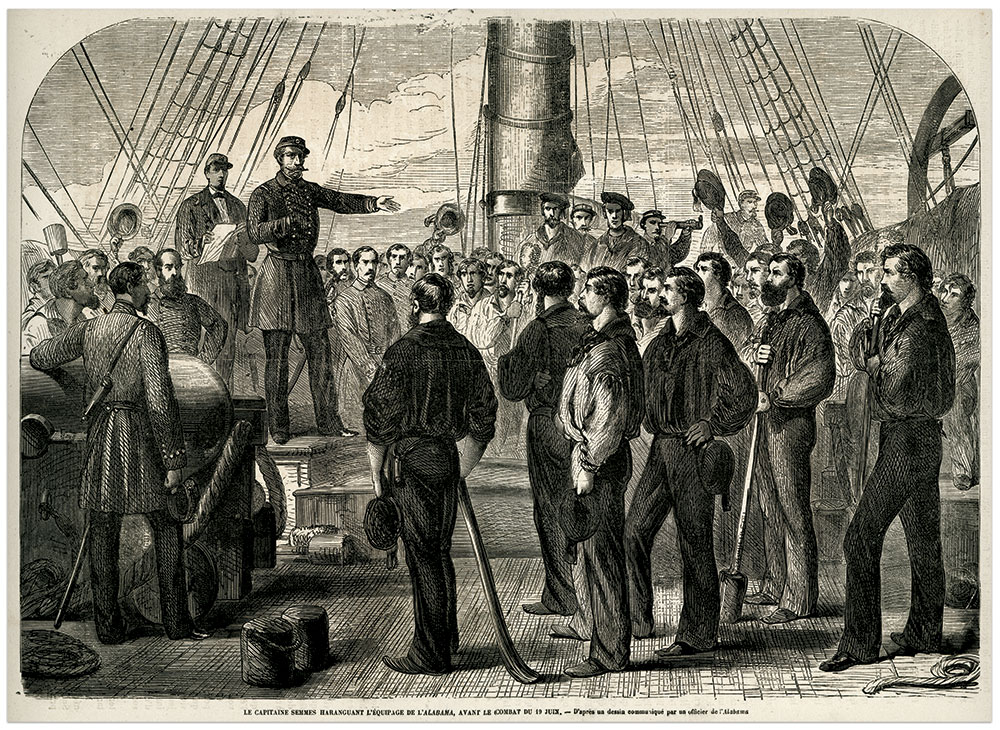

Before the epic battle, Semmes mounted a gun carriage and addressed the officers and crew with a stirring appeal to fulfill their mission, reminding them of their glorious achievements, and expressing his confidence in their success. “Defend the flag of your young nation!”

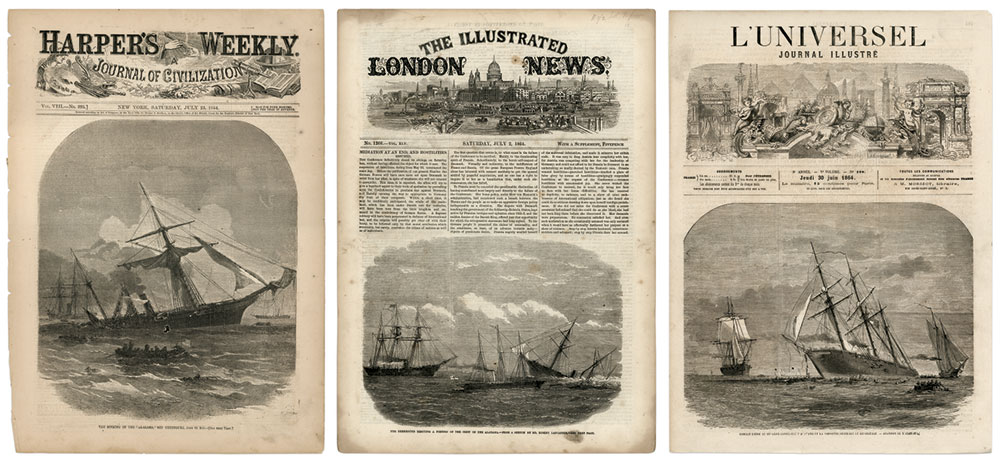

The fight has been the subject of intense interest and speculation since the moment the first shot was fired by the Alabama. In slightly over an hour of bloody combat, the struggle concluded with the destruction of the Alabama. It is generally accepted that the superior marksmanship of the well-trained crew of the Kearsarge and the defective munitions of the Alabama decided the raider’s fate. Concealed armor on the Kearsarge was also a factor, and it is unknown whether or not Semmes’ was aware of this fact and if it would have dissuaded him from fighting.

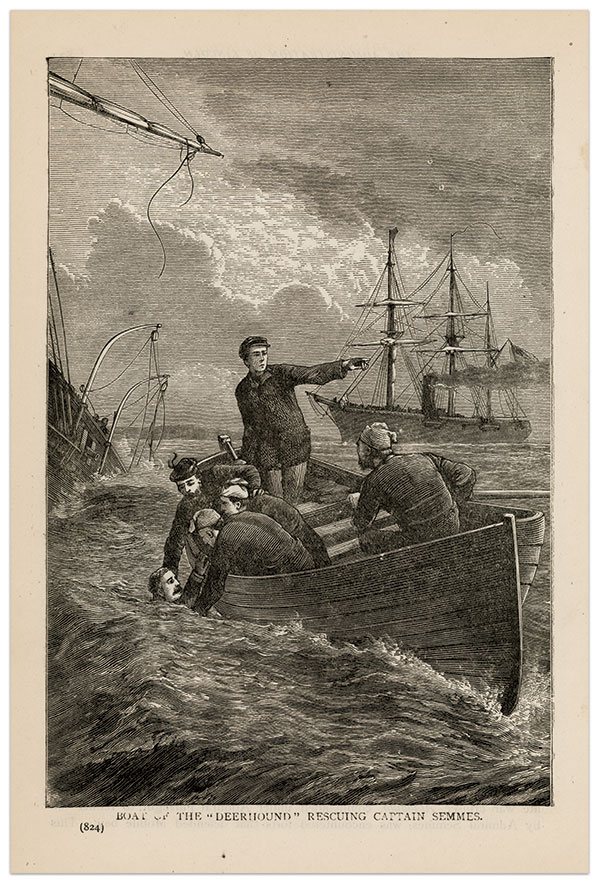

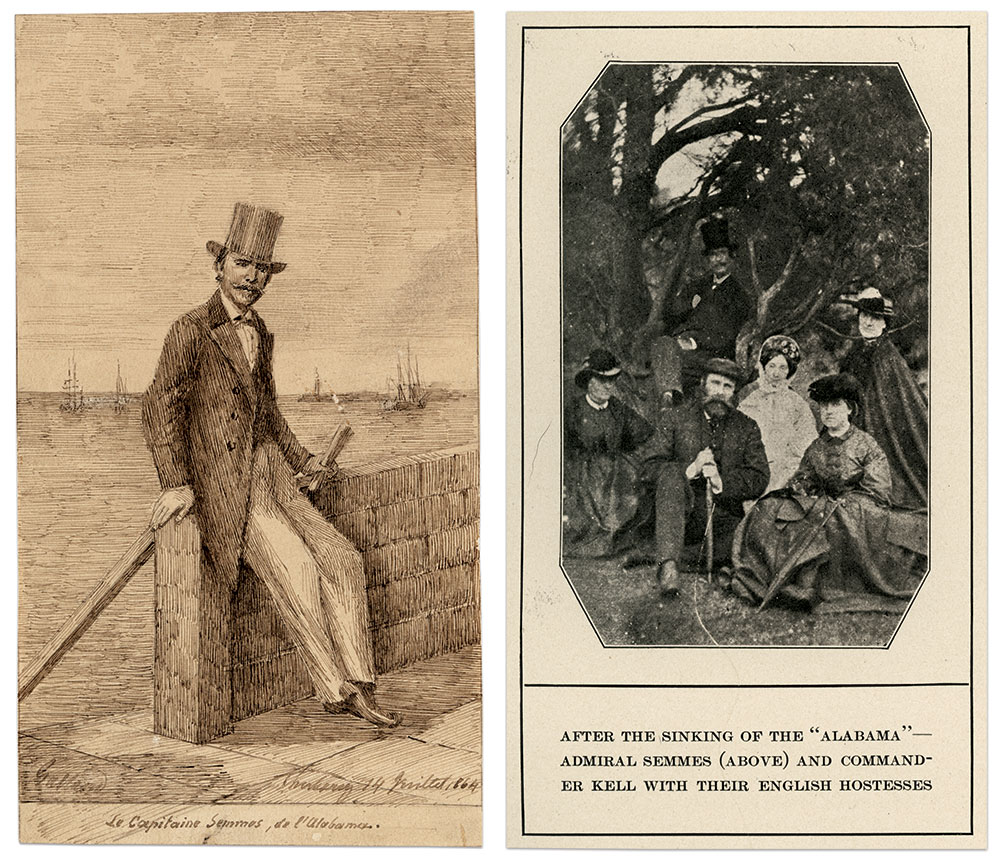

After Semmes defiantly tossed his sword into the frigid waters of the English Channel the crew of the British yacht Deerhound rescued him, Lt. Kell, and a number of his men from drowning. They were transported to the English port of Southampton, where Semmes and Kell were praised for their valor and besieged by local admirers to have their photographs taken.

Not all Semmes’ men enjoyed the adulation of the British. The casualty list totaled 40, including 19 fatalities (nine killed and 10 drowned) and 21 wounded.

In his published memoirs, Semmes reflectively shared his emotions during his darkest moment: “No one who is not a seaman can realize the blow which falls upon the heart of a commander, upon the sinking of his ship. It is not merely the loss of a battle—it is the overwhelming of his household, as it were, in a great catastrophe. The Alabama had not only been my battlefield, but my home, in which I had lived two long-years. And in which I experienced many vicissitudes of pain and pleasure, sickness and health. My officers and crew formed a great military family, every face of which was familiar to me; and when I looked upon my gory deck, toward the close of the action, and saw so many manly forms stretched upon it, with the glazed eye of death, or agonizing with terrible wounds, I felt as a father feels who has lost his children—his children who had followed him to the uttermost ends of the earth, in sunshine and storm, and been always true to him.”

Semmes suffered a minor wound to his right hand caused by a fragment of an exploding shell from the Kearsarge. He sustained three small cuts determined by Dr. John Wiblin, a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, as not serious.

The battle between the Alabama and the Kearsarge, last of the great wooden warships, is remembered as one of the most celebrated naval engagements of the Civil War. It also marked the end of a remarkable hunting career. The Alabama captured more than 60 U.S. merchant vessels, and destroyed the warship Hatteras after a 13-minute battle off Galveston, Texas, on Jan. 11, 1863.

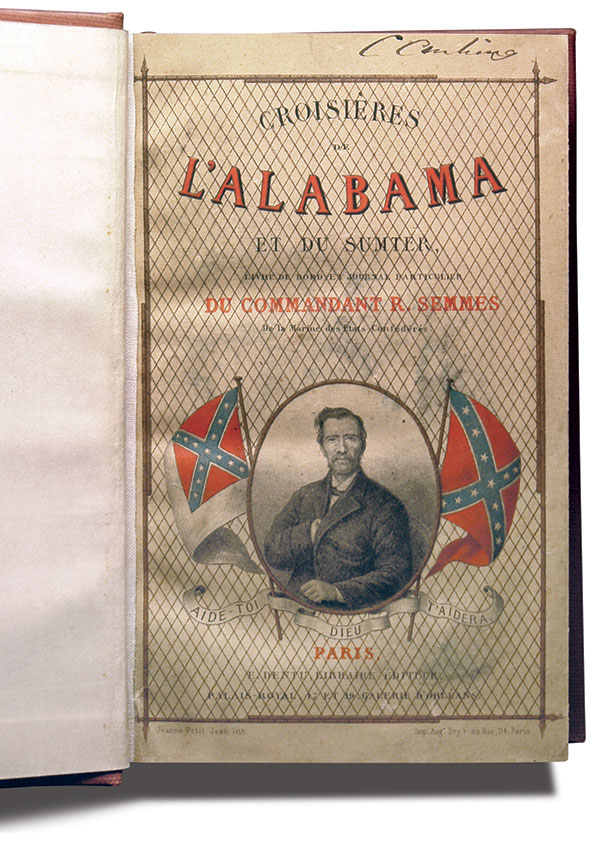

The loss of the Alabama ended Semmes’ career as a raider. He wrote with evident pride of his accomplishments on the high seas in the first paragraph of his 833-page Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States published in 1869: “The Alabama was the first steamship in the history of the world—the defective little Sumter excepted—that was let loose against the commerce of a great commercial people. The destruction she caused was enormous. She not only alarmed the enemy, but she alarmed all the other nations of the earth which had commerce afloat, as they could not be sure that a similar scourge, at some future time, might not be let loose against themselves.”

Semmes left England for home later in 1864, arriving in Mobile on December 18. His second oldest son, Oliver, joined him on an arduous journey across the ravaged South. A cadet at West Point in 1861, Oliver had resigned his commission four weeks before his father did. He rose to the rank of artillery major in the Trans-Mississippi Department and member of the staff of Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor. Father and son were welcomed as heroes. Accolades followed Semmes as he made his way to Richmond.

In February 1865, Semmes received a promotion to rear admiral and command of the James River Squadron’s three ironclad rams and a number of wooden steamers.

There was little action until the evacuation of Richmond on April 2, 1865. Semmes ordered the destruction of his fleet, organized his sailors and naval cadets into a brigade, and departed the capital city on the last train. At Danville, Va., on April 6, Semmes received a temporary rank as brigadier general in the Confederate army.

Semmes and his Naval Brigade, numbering 246 sailors, received orders to link up with President Davis at Greensboro, N.C., but Davis had gone on to Charlotte. After Johnston surrendered his Army of Tennessee at Durham on April 26, 1865, Semmes surrendered and received his parole at a Greensboro hotel. He signed the document with his name with his dual navy and army ranks.

Postwar pursuits and politics

Semmes received a parole and returned to Alabama. On Dec. 5, 1865, a detachment of U.S. Marines arrested him in Mobile. Charged with illegally escaping Union custody after the surrender of the Alabama at Cherbourg, federal authorities confined Semmes at the Navy Yard in Washington to await trial. But the prosecution of his case hit an impasse with disagreements between President Andrew Johnson, his Cabinet and the Navy about the extent of the charges. A recent Supreme Court case was used to overrule the decision to try the former Confederate rear admiral in a military court and Semmes gained his release on April 7, 1866, without the anticipated sensational trial for piracy.

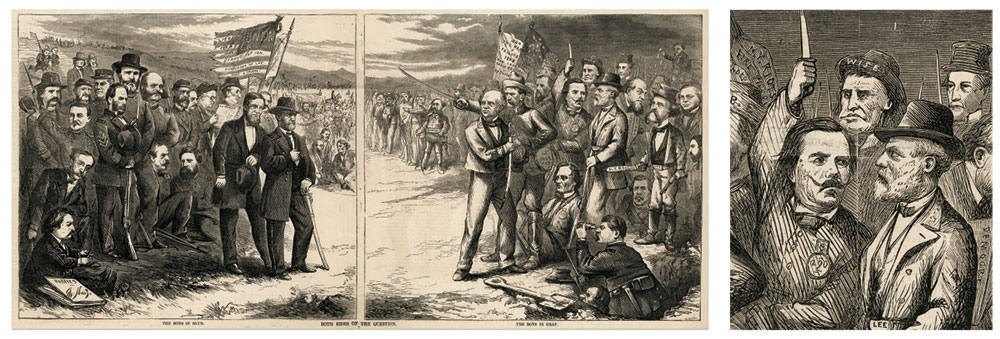

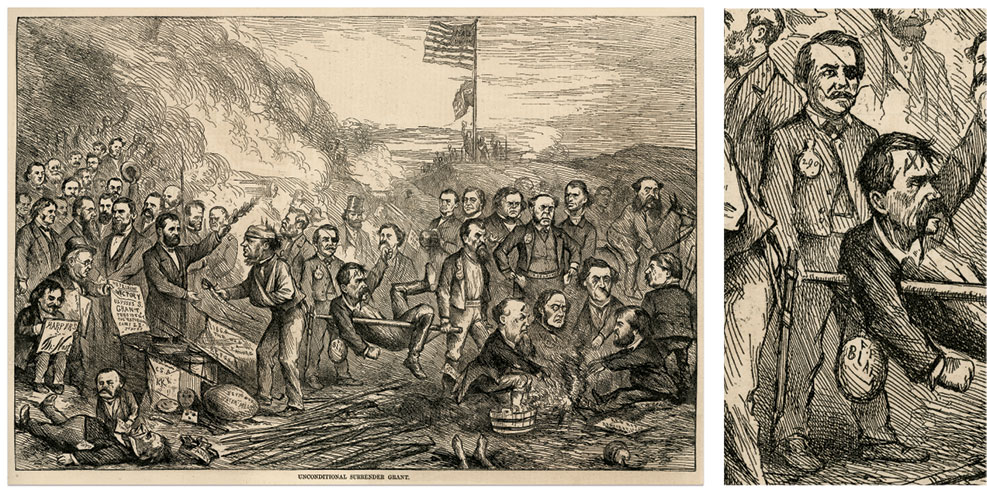

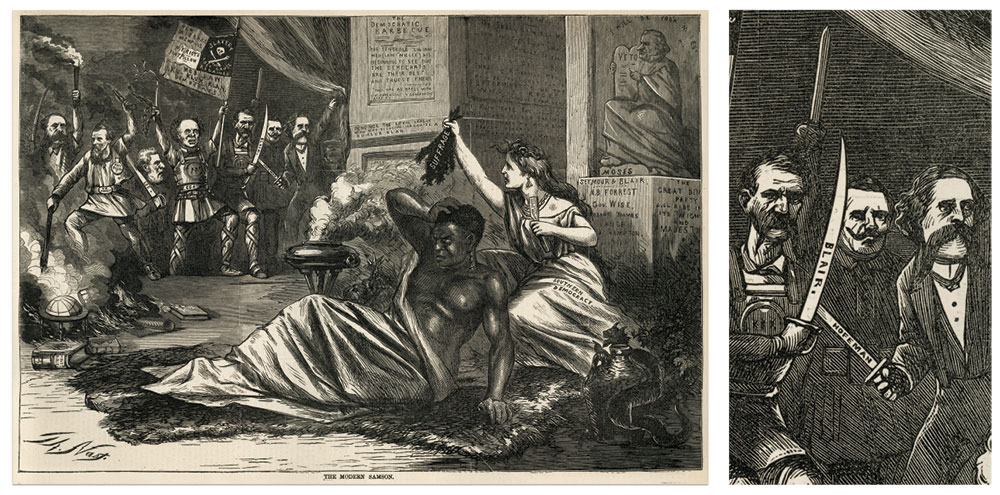

Semmes’ characterization as a pirate dogged him for the rest of his days. Republicans made political hay against him in the election of 1868, the first presidential campaign of the Reconstruction era, pitting triumphant war hero Ulysses S. Grant against the Democratic contender, Horatio Seymour. For the most part, the Democratic Party represented the recently franchised South, although three of the former Confederate States, Texas, Mississippi and Virginia, were not yet restored to the Union.

Editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast portrayed the Democrats as the party of traitors, and used his illustrations to vilify former Confederate statesmen and leaders. In several of his elaborate tableaux, he included Admiral Raphael Semmes, sometimes simply a face in the crowd, in other instances a major focal point. Semmes thought all of the depictions of him by Nast were libelous.

Semmes shared his thoughts on the recent unpleasantness in his Civil War memoirs. The book features a lengthy defense of the legitimacy of Southern secession and the role slavery played in it. The war in fact was about slavery, and Semmes knew it. At his home in Mobile, he enslaved three people. Semmes felt that slaves and their masters had an understanding of their roles, their mutual benefits and responsibilities. He regarded the institution as a benevolent two-way contract.

Semmes held various public positions, including a professorship in philosophy and literature at Louisiana State Seminary (now Louisiana State University), a county judge, and a newspaper editor. He continued his legal practice, specializing in maritime law.

On Aug. 30, 1877, at age 68, Semmes’ turbulent life came to an abrupt end. He reportedly succumbed to food poisoning from contaminated shrimp. He was buried in Mobile’s Old Catholic Cemetery.

The Admiral is remembered for his daring deeds as captain of the “Ghost Ship,” his devotion to God, family and country. His epitaph reads “but above all, and always, a gentleman.” His fame and relevance to naval warfare extended far into the 20th century. Kaiser Wilhelm II, head of the Imperial German Navy, once remarked: “I reverence the name of Semmes…At every conference with my admirals, I counsel them to read and study closely Semmes’ Memoirs of Service Afloat. I myself feel constant delight in reading and rereading the mighty career of the ‘Stormy Petrel.’” Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty and British Prime Minister during World War II, paid homage to Semmes with this conclusive statement: “In my opinion, he was the greatest admiral of the Nineteenth century.”

Postwar memorabilia

Special thanks to Dr. Norman Delaney for his encouragement and research assistance; to Nick Beeson, Curator of Collections, History Museum of Mobile, for providing Raphael Semmes’ photographs and documents; to Michael Hammerson for research assistance; and to H. Scott Wolfe for his tireless efforts in preparing this iconography for publication.

References: Roberts, Semmes of the Alabama, Bowcock, Andrew. “Photographs On Board CSS Alabama,” Military Images (March-April, 2007); “Captain John A. Winslow. Message from the President of the United States,” House of Representatives, 38th Congress, 2nd Session. Ex. Doc. No. 6; Rigby, Maurice. UK People in the Civil War, acwrt.org.uk/post/uk-people-in-the-civil-war; Miller, Ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes, Vol. 6; Emails with Michael Hammerson, April 29, May 2 and July 23, 2023; Boykin, Ghost Ship of the Confederacy; Semmes, Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War; Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States; 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules, Kell interview original published in The Atlanta Constitution and reprinted in the Irvine Express, Irvine, Strathclyde, Scotland, May 9, 1884; Raphael Semmes military service record, National Archives; Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Bangor, Maine, May 9, 1865; Bull and Denfield, Secure the Shadow: The story of Cape photography from its beginnings to the end of 1870.

Cliff Krainik is an independent historian and nationally recognized appraiser of historic photography. He and his wife, Michele, co-authored Union Cases: A Collector’s Guide to the Art of America’s First Plastics. Cliff is a regular contributor to White House History Quarterly and The Daguerreian Annual. He maintains an avid interest in the career of Rear Adm. Raphael Semmes.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Semmes: An iconography of Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes, C.S. Navy”

Comments are closed.