By Richard A. Wolfe, featuring images from the author’s collection

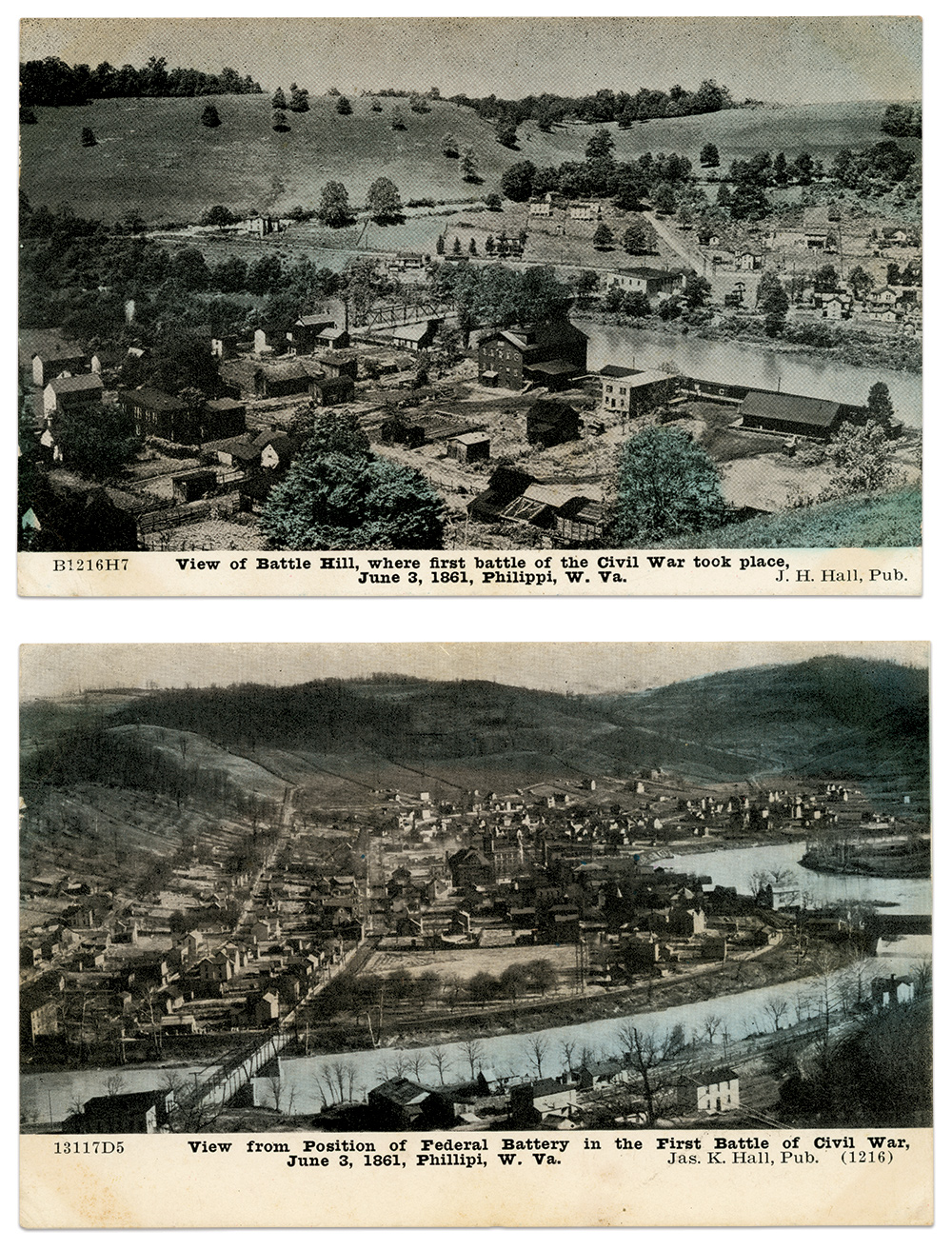

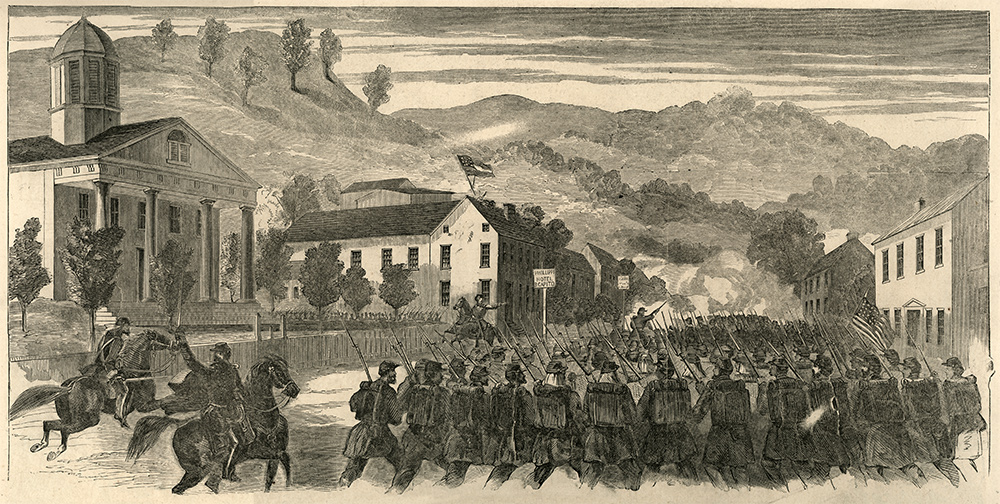

As dawn broke on June 3, 1861, the sound of artillery fire shook the quiet town of Philippi, starting the first land battle of the Civil War. Four days earlier this Virginia community of 200 became a camp for 750 soldiers of the Confederate States of America. These ragtag Confederates had retreated from the railroad junction at Grafton when threatened by Union troops moving via the railroad from Wheeling and Parkersburg. Following the brief artillery bombardment, two columns of 1,500 men each rushed in and the Confederates retreated toward Beverly. These Union troops had marched all night, in a driving rain, from Grafton.

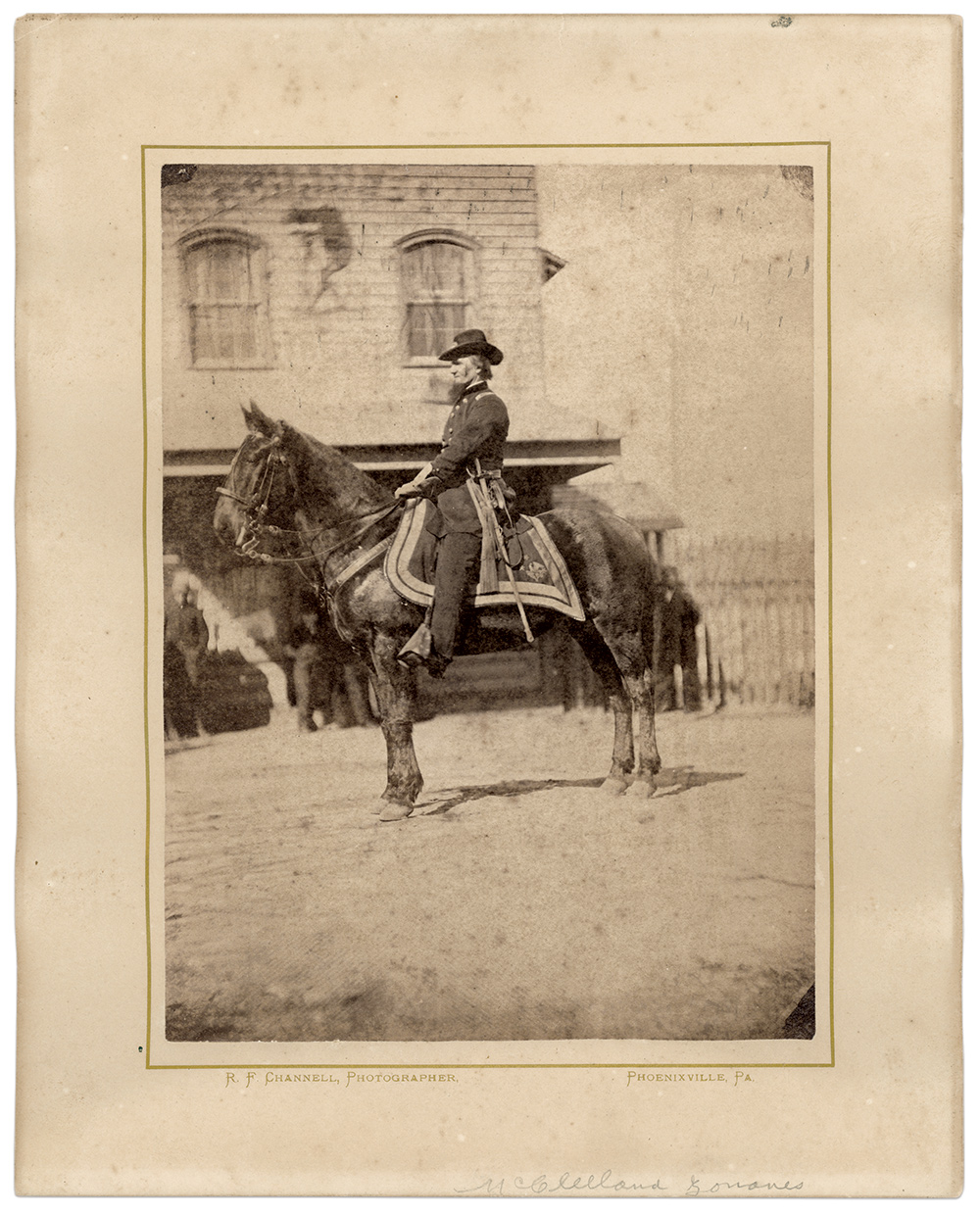

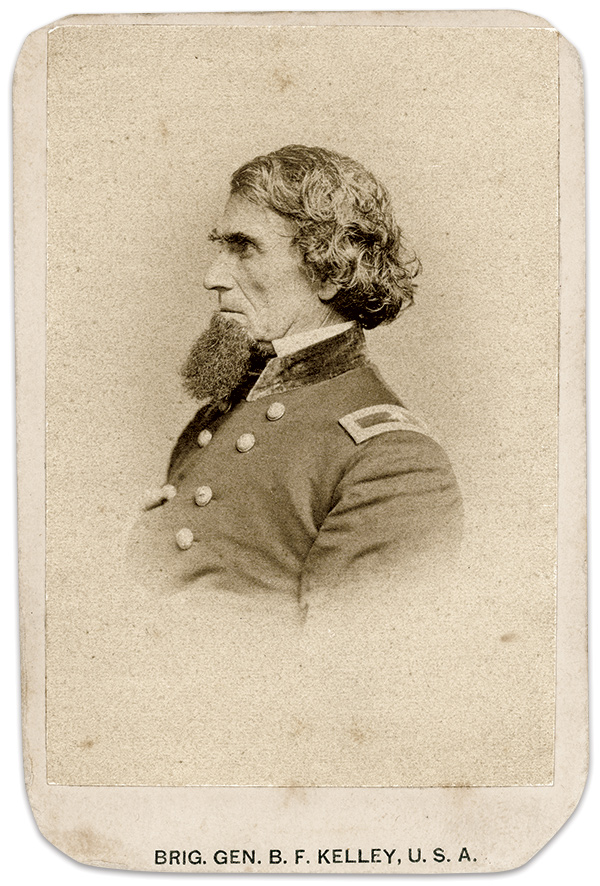

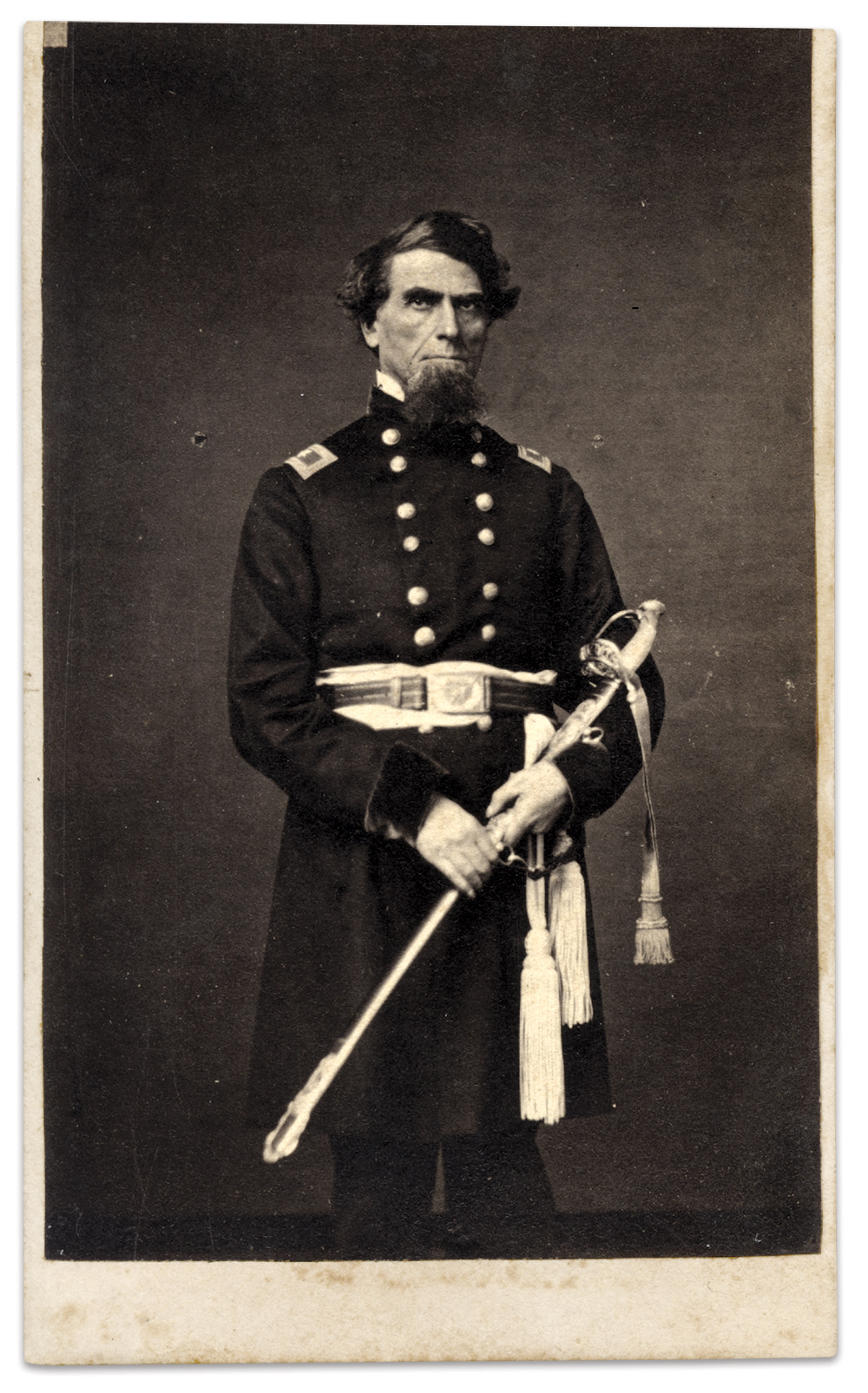

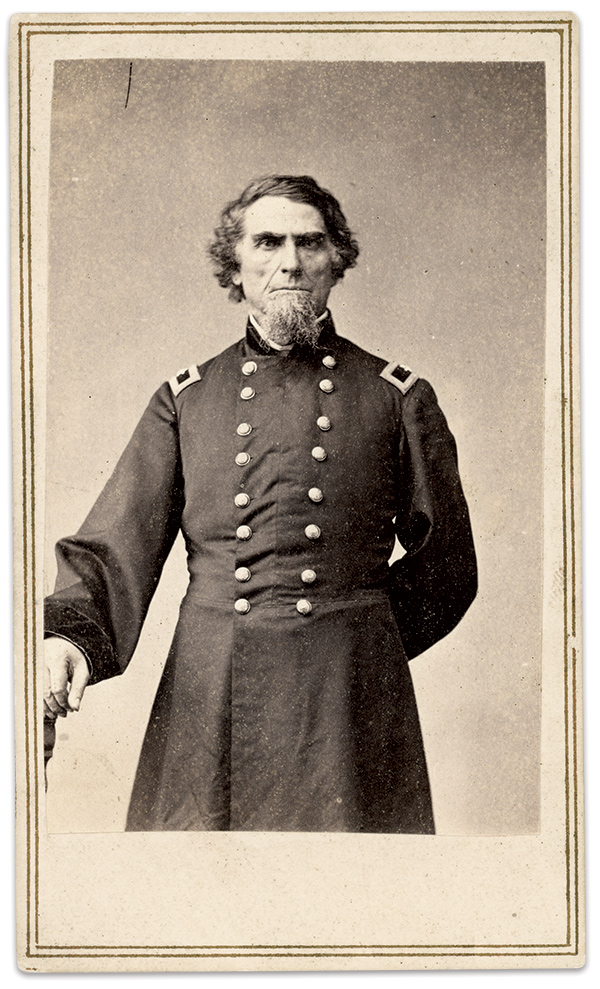

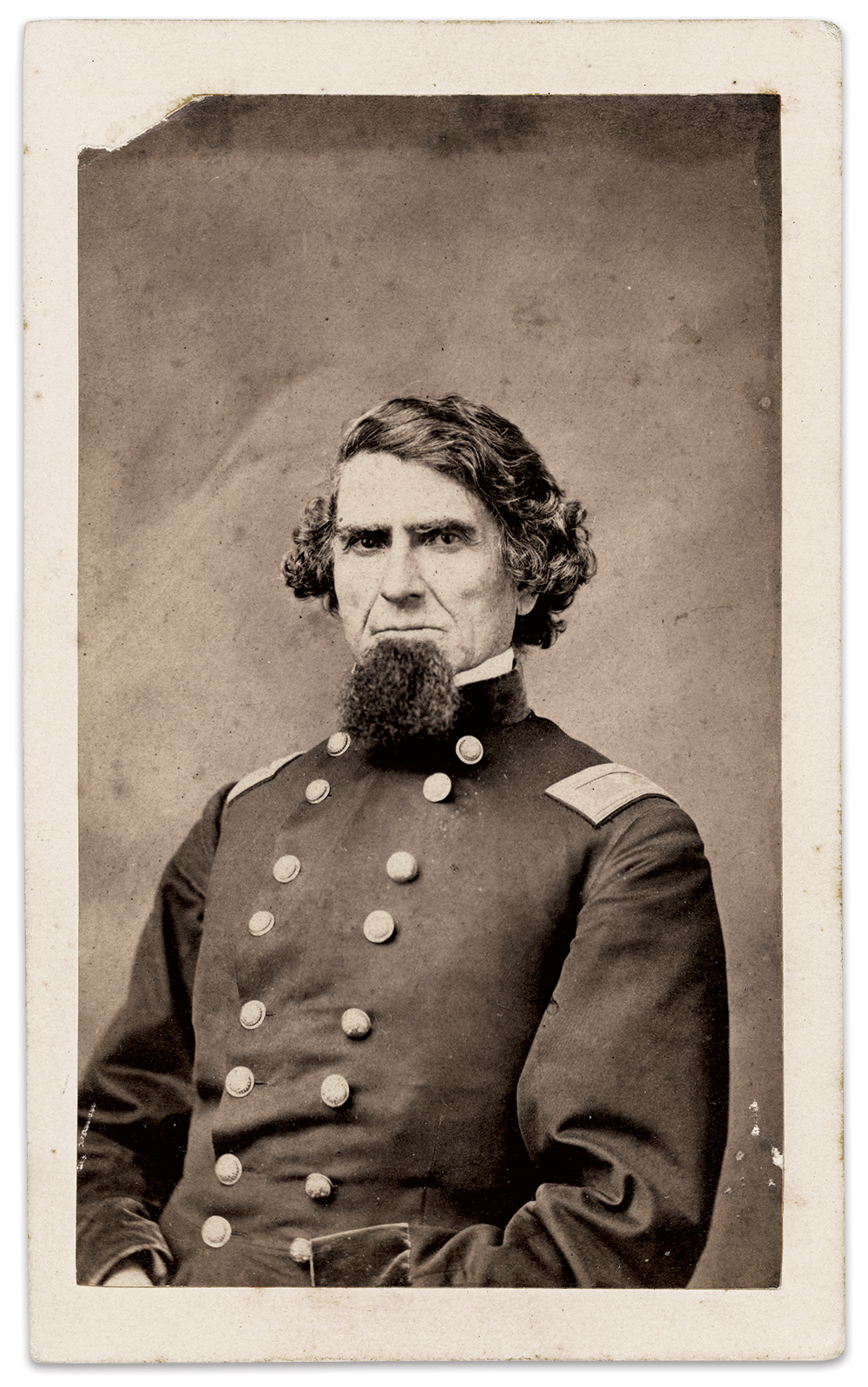

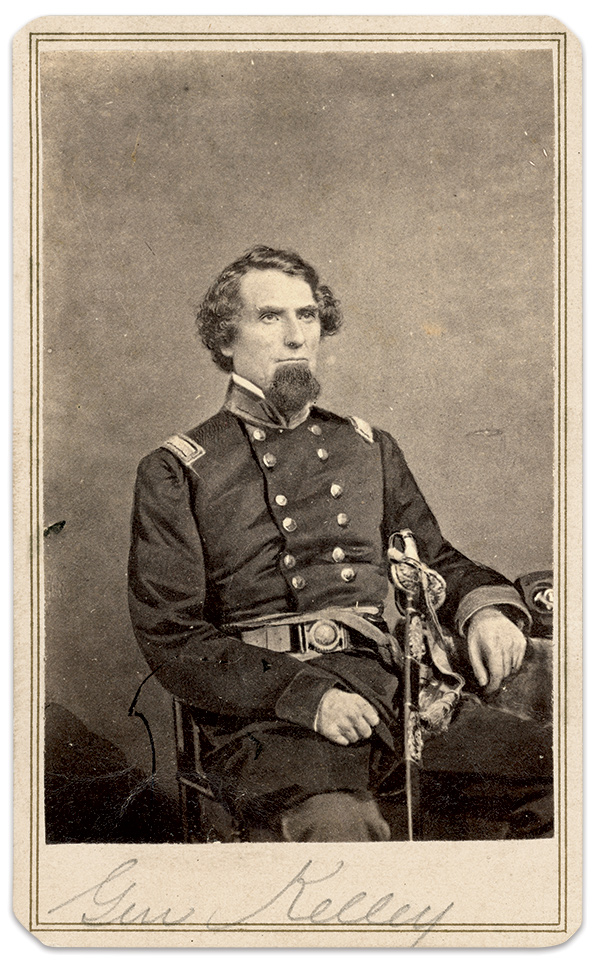

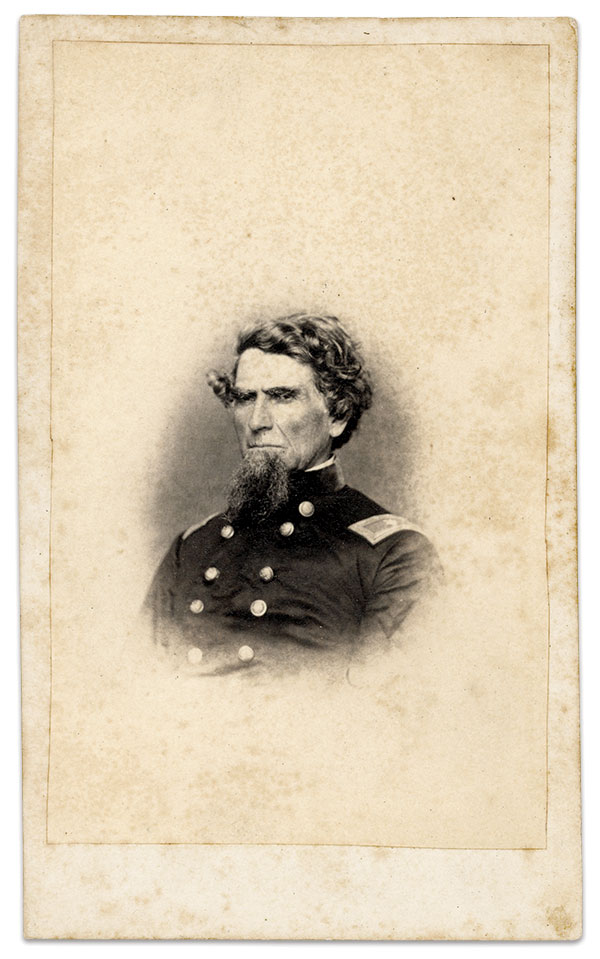

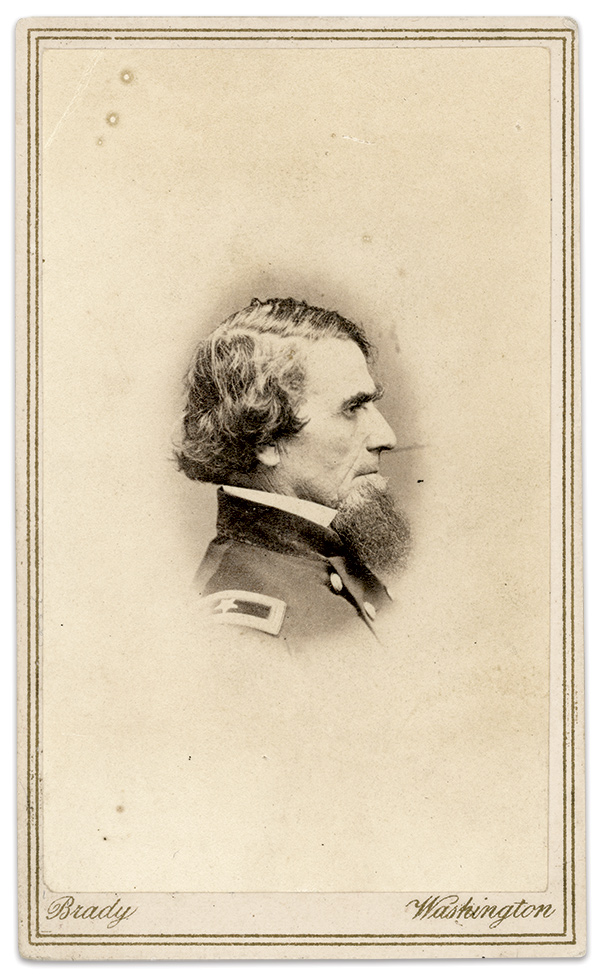

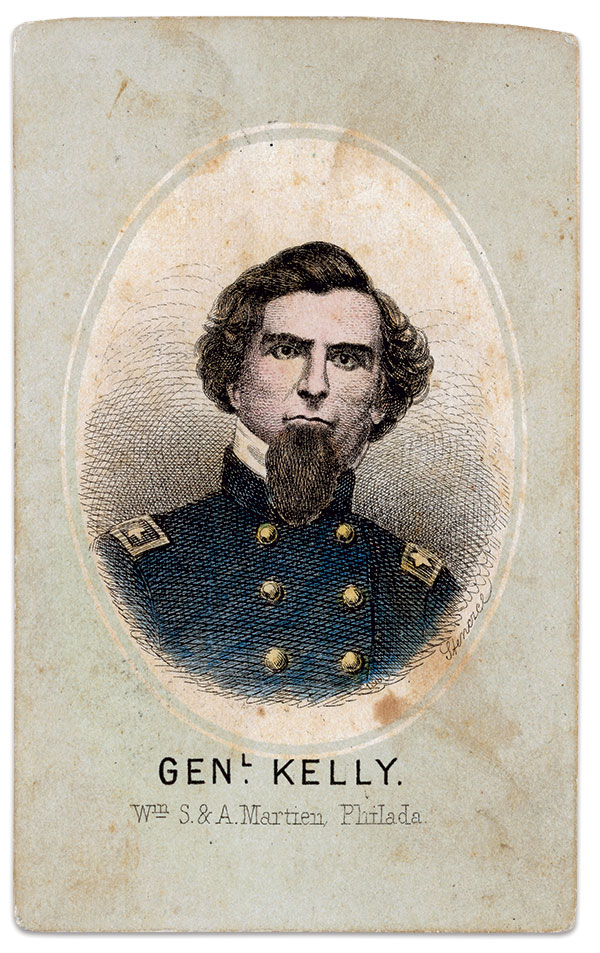

The overall commander and the head of one column of Union troops, Col. Benjamin F. Kelley, presented a target mounted on horseback and dressed in a fine blue uniform. As he pursued fleeing Confederates, one of them shot him in the chest. Kelley fell from his horse into the street.

The shot that dismounted Kelley came from an old-fashioned horse pistol fired by Quartermaster William Simms. The ball struck Kelley in the chest, passed between the ribs and rested against his shoulder blade. Men of Kelley’s 1st Virginia Infantry apprehended Simms and decided to hang him. But cooler heads prevailed when Col. Frederick W. Lander and the regiment’s officers saved Simms by declaring him a prisoner of war.

Soldiers carried Kelley to the nearby abandoned Ashenfelter house and laid him on the porch. Bleeding profusely and believing his wound fatal, Kelley declared, “I expect I shall have to die,” adding, “I would be glad to live if it might be, that I might do something for my country, but if it cannot be I shall have, at least, the consolation of knowing that I fall in a just cause.”

Lander returned to Grafton thinking that Kelley had died. The next morning’s edition of the New York Herald reported Kelley’s death.

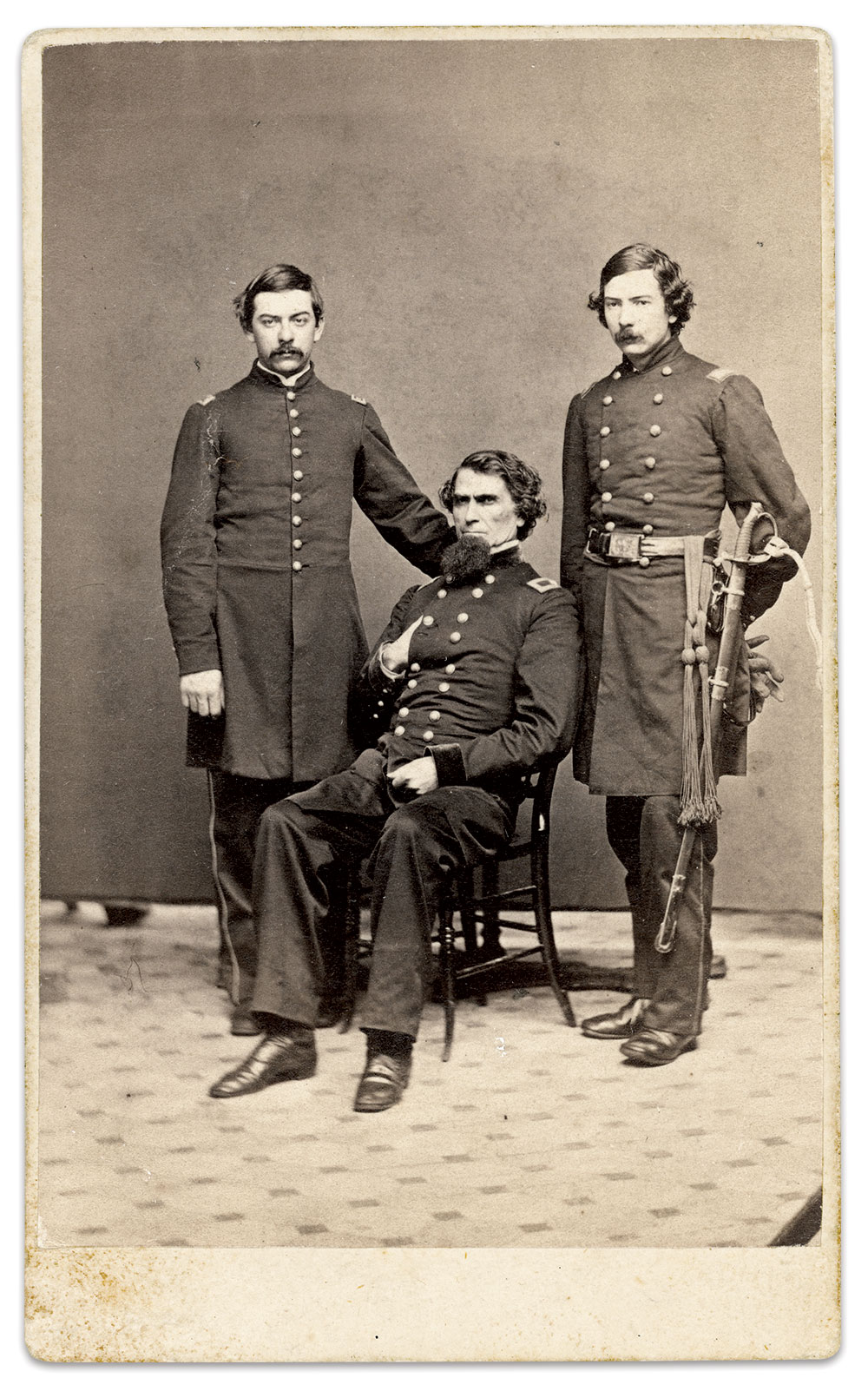

The report proved incorrect. Kelley survived and returned to active duty. A look at his war service reveals an able tactician and aggressive soldier placed in difficult positions in unstable territory prone to raids by regular and irregular forces.

Business, family, and war

Born April 10, 1807, in New Hampton, N.H., he was the son of William B. Kelley and Mary (Smith) Kelley. His father served on the town’s first Board of Selectmen.

Kelley had a passion for the military from a young age. Hopes to attend West Point faded after his father died in 1823. Kelley, 16, became an apprentice for John Simpson in Boston to learn the mercantile business. In the summer of 1826, he completed his apprenticeship and immigrated to Wheeling, Va., where he lived with his brother and went to work. About two years later, following the death of his brother, Kelley entered into an agreement with wealthy merchant John Goshorn to clerk for two years. At the end of the term, Goshorn elevated Kelley to a partner.

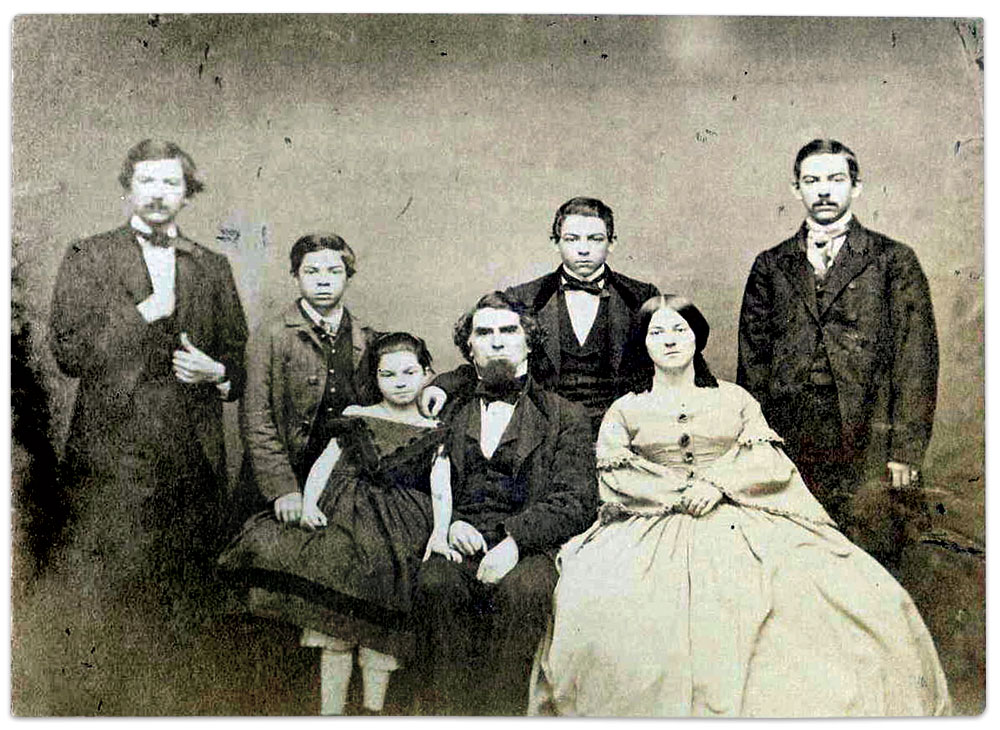

In 1832, Kelley married Mary King. Tragedy struck the following year when she died of cholera, leaving a baby behind. The child died about two years later.

Despite the devastating loss, Kelley built his reputation as a respectable merchant in Wheeling. In 1835, he did what every up-and-coming businessman dreams of—he married the boss’s daughter. The union of Kelley and Isabel Goshorn produced six children.

In the 1840s, Isabel showed signs of mental problems. A concerned Kelley took her to be treated in a progressive Philadelphia hospital specializing in psychiatric care. The hospital became her permanent residence. Kelley and the children remained in Wheeling until about 1850, when they moved to Philadelphia to be near her. He worked as a salesman and then a freight agent for the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. Isabel died in 1860.

Kelley maintained contact with friends in Wheeling. When secession talk grew louder, he urged the western counties to remain loyal to the Union and to arm themselves. On April 17, 1861, the Virginia Convention voted to send the ordinance of secession to the citizens of the commonwealth. Leaders of the western counties called a convention in Wheeling. On May 13, representatives elected to remain in the U.S.—sewing the seeds of statehood.

Meanwhile, pro-Union companies formed. In Wheeling, the 1st Virginia Loyal Infantry organized. When it came time for a regimental commander, the unanimous choice of the officers and privates of the regiment was Ben Kelley. Loyal citizens supported his nomination.

On the evening of May 22, Kelley received a telegram at his home in Philadelphia with a request to command the first Union regiment raised in a Southern state. The next morning, he resigned from the railroad and left for Wheeling.

Upon his arrival on May 24, he found 10 companies of soldiers in name only. Enthusiastic and untrained, they lacked tents, camp equipage, baggage-wagons, haversacks, cartridge boxes and canteens. They were in no condition to defend the city or assume offensive operations.

Kelley had much work to do.

The “Napoleon of the Northwest” wins at Philippi

One hundred miles east of Wheeling, men of opposing loyalties armed for war in dangerously close proximity. In Grafton, a town at the junction of the B&O and Northwest Virginia railroads, Capt. George Latham recruited a company of Union soldiers. Three miles west in the community of Pruntytown, Confederate soldiers mustered.

On May 22 in Fetterman, a village between the two places, Confederate Daniel Knight killed Union soldier Thornsbury Bailey Brown. The next day, Capt. Latham and his company left Grafton for Wheeling.

Confederates occupied Grafton. When the commander of this force, Col. George Porterfield, learned of Union troops massing in Wheeling, he dispatched men to torch wooden trestles on the railroad west of Grafton.

News of the burned bridges made its way to Kelley in Wheeling. He telegraphed the commander of the military Department of Ohio, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, in Cincinnati. The charismatic up-and-coming officer ordered Kelley to march for Grafton with as many troops as he could muster.

Kelley followed McClellan’s direction and soon left Wheeling with his regiment. About 60 miles into the campaign, near Mannington, they discovered the two burnt trestles. Kelley paused to rebuild them before continuing the march towards Grafton.

On May 30, Kelley and his troops arrived at their destination and found Grafton unoccupied. Porterfield had decamped with his Confederates the night before and withdrew about 15 miles south to Philippi.

In Grafton, Ohio and Indiana troops dispatched by McClellan joined Kelley, swelling the overall Union force to about 3,000 men. Kelley helped develop a two-pronged plan of attack against Porterfield: One column moving more or less a straight line to assault the Confederates and the second circling around town to cut off their retreat.

It was a good plan, but the fog of war changed the execution.

On June 2, 1861, Kelley, in command of the second column, boarded an eastbound train with a 1,500-man force composed of his regiment and the 16th Ohio and 9th Indiana infantries. Six miles later, everyone disembarked and commenced a 22-mile march in unseasonable warm weather. That evening, Kelley halted his column to eat when rain began to fall. The march resumed as downpours slowed the advance through the night.

While Kelley’s column struggled in the deluge, the second column, commanded by Col. Ebenezer Dumont of the 7th Indiana Infantry, left with 1,500 men from his regiment and the 6th Indiana and 14th Ohio infantries. Moving along the Fairmont Beverly Turnpike, they had a relatively easy time on the march, arriving on a hill overlooking Philippi just before sunrise on June 3. Dumont prepared his men for the attack, deployed two artillery pieces, and waited.

Kelley and his men were a mile away from Philippi when they heard the sound of cannon fire. An anxious Dumont had opened the fight. Kelley double-quicked the exhausted column and entered the middle of town instead of the south end due to a confused civilian guide upon whom Kelley had relied.

Here they encountered Porterfield’s Confederates fleeing before them, labeled “The Philippi Races” by the Northern press. It was also here that the skirmish in the streets unfolded and Kelley received the pistol shot that knocked him off his horse.

The wound proved non-fatal. While Kelley took up residence in the Grafton Hotel to recover, he received accolades for his service. Grateful citizens of Wheeling presented Kelley with a fine horse named Philippi. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer published an editorial by a correspondent named Kanawa describing Kelley as the “Napoleon of the Northwest.”

“A little dash is a good element”

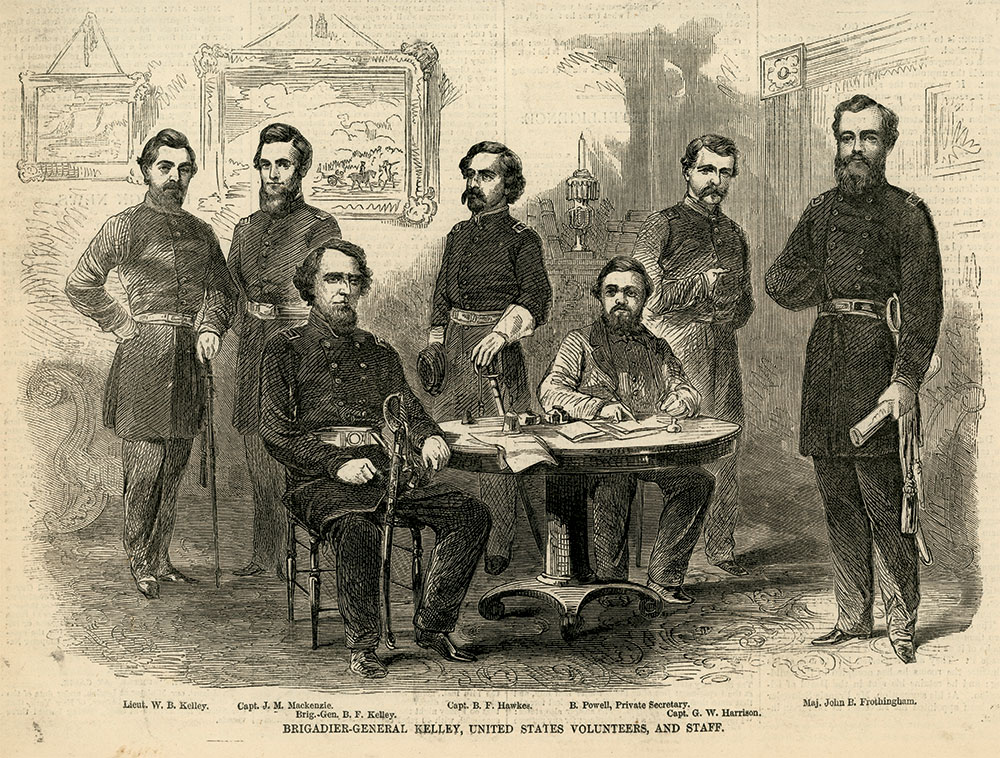

In recognition of his service, Kelley received his brigadier general’s star and command of the District of Grafton. The area encompassed the B&O Railroad from Cumberland to Wheeling and the Northwest Virginia Railroad from Grafton to Parkersburg. Kelley’s peacetime employment as a freight agent benefitted him here. Kelley’s district composed part of the Department of Western Virginia commanded by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans.

On Oct. 22, 1861, General of the Army Winfield Scott, about a week away from retirement, issued one of the last orders of his storied career to Kelley. Scott telegraphed him to move on Romney and to take command of the Department of Harpers Ferry and Cumberland until the arrival of Brig. Gen. Fredrick W. Lander.

Confederates commanded by Col. Angus McDonald held Romney, about 90 miles due east of Grafton. Kelley concentrated his forces at New Creek, about 26 miles from Romney.

At midnight on October 25, Kelley moved out with his column of cavalry at each end, and infantry and artillery in the middle. Captain John Keys of Pennsylvania’s Ringgold Cavalry led the advance. Following the troopers were the 7th Virginia Infantry and one company each of the 3rd and 4th Virginia infantries, the 8th Ohio Infantry, and a 6-pounder cannon. The 4th Ohio Infantry and a detachment of infantry that accompanied a 12- and a 6-pounder joined the column. Captain McGee’s cavalry brought up the rear.

McDonald’s Confederates commenced firing when Kelley’s column closed within six miles of Romney. Kelley brought his artillery to the front and continued the advance. At Mechanicsburg Gap, Kelley discovered the enemy entrenched in a commanding position in Indian Mound Cemetery on the west side of Romney. Confederate artillery fire from the position proved impossible to silence.

Kelley decided to charge them. Noting that his artillery had a clear field of fire on a strategic bridge and ford, Kelley acted quickly. He pushed his infantry across the bridge, followed closely by a cavalry charge on the ford. The Confederates fled through town. On the eastern side of town, the Confederates attempted to rally and make a stand, but Capt. Keys and his Ringgold Cavalry hit and scattered them.

Kelley established Camp Keys in recognition of the gallantry of the captain of the Ringgold Cavalry. Situated on the Northwest Turnpike less than 50 miles from Winchester, the position added additional protection to the B&O Railroad.

Kelley proved a team player during Stonewall Jackson’s Winter Campaign of 1862. Jackson left Winchester and moved north on the Union garrison at Bath (present day Berkeley Springs), and then drove the federals across the Potomac to Hancock, Md. As Union forces prepared for Jackson to besiege the town, Frederick Lander, who had prevented a hanging after the skirmish at Philippi, arrived on the scene. Now a brigadier general, Lander fired off urgent requests for re-enforcements to Maj. Gen. Nathanial Banks, who refused, and Kelley, who acted.

Kelley created a diversion against Jackson’s rear. He directed Col. Samuel H. Dunning and his 5th Ohio Infantry to demonstrate against Confederate militia at Blues Gap. Then, on January 6, Kelley marched his command 15 miles in the cold and six inches of snow, defeated the Confederates at Blues Gap and marched back to camp. On January 7, Jackson halted his assault on Lander. Did Kelley’s movements cause Jackson to be concerned with the safety of his army, or did Jackson determine that crossing the river under fire would be too costly?

Lander stated of Kelley, “see the difference between Kelley and the Army of the Potomac.” He added, “A little dash is a good element.”

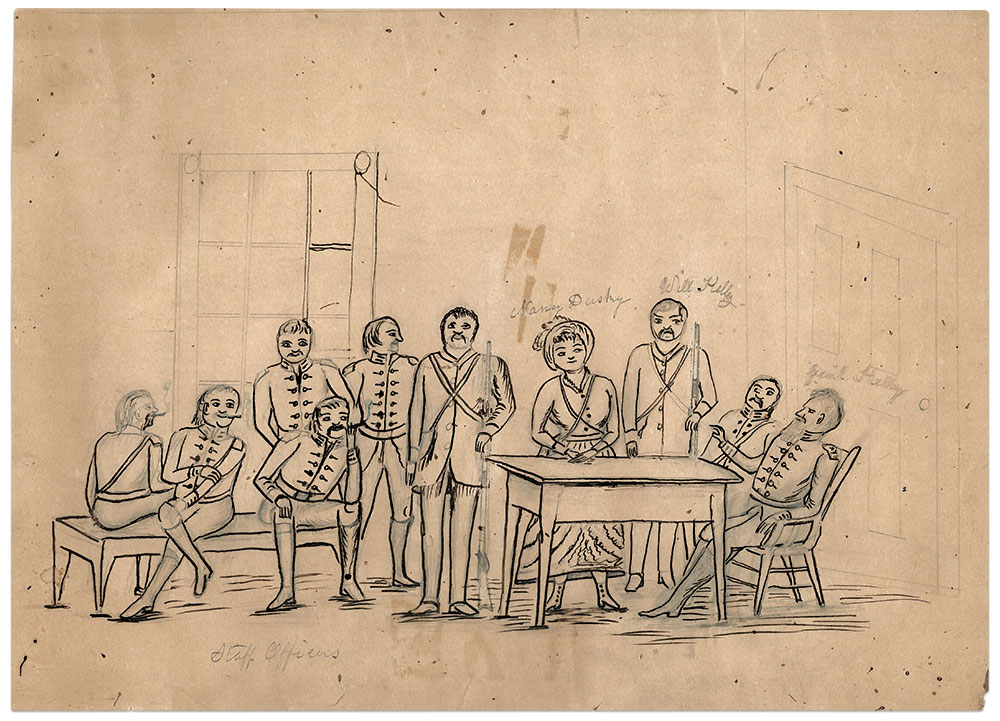

The interrogation of Nancy Dusky and the march to Statehood

In 1862, Kelley helped maintain civil government as the Restored Government of Virginia raced towards the creation of West Virginia. He and his staff, and a cavalry detachment patrolled a four-county area to quell guerilla activity: Wirt, Calhoun, Roane and Clay.

In the Wirt County town of Burning Springs, the Ringgold Cavalry captured guerillas, including Nancy Dusky, a spy and lookout for one local band. Her father, Dan Dusky, was a prominent rebel. Her brothers were also members of the group.

Kelley and his staff interrogated Nancy, a girl about 18 years old dressed in a calico dress, cartridge box and belt, and a straw hat with a feather in it. So the oft repeated story goes, Kelley said to her, “Nancy where are the rebels, how many are there?” She refused to answer. The general then asked about fords across the swollen Little Kanawha River. The defiant rebel girl again refused to answer.

Kelley switched tactics to a softer approach by dispensing fatherly advice. “You have given the Union forces a good deal of trouble, if you persist in your operations, you are liable to get into very serious trouble. You must quit this business. Nancy, you are young and handsome and would be a good wife for some worthy man. Get married, settle down, and give us no more trouble.” She broke her silence with a comment about not being able to find a good man.

Kelley replied, “You may have the pick of my staff that includes my son.” Nancy surveyed the room and stated, “I believe that I would prefer the General himself to any of his officers.” At that, Kelley ordered his staff to release her. He didn’t have any real evidence to arrest her or maybe Nancy’s flattering remarks influenced the old general.

Despite the best efforts by Kelley and other military and political leaders, a Confederate raid in April 1863 caused consternation. Generals John D. Imboden and William E. “Grumble” Jones launched a two-pronged attack that destroyed railroad track, trestles, bridges, trains and 150,000 barrels of oil. Plus they captured 1,200 horses, 1,000 head of cattle, and 500 prisoners. Citizens blamed the government and the military for allowing the raid to happen without much of a fight.

The raid did not prevent Statehood on June 20, 1863, and the creation of the military Department of West Virginia.

The War Department placed Kelley in command. He created a mobile force to protect the new state, converting the 2nd, 3rd and 8th West Virginia infantries to mounted infantry and eventually cavalry. Capable Brig. Gen. William W. Averell became the commander. These regiments remained constantly in the saddle, fighting rebels throughout the state.

Enemies from outside and inside the state

As West Virginians celebrated their first Independence Day as a state and victory at Gettysburg, Kelley received an urgent telegram from Washington. Major General Henry W. Halleck ordered him to move all available forces to Hancock and strike Gen. Lee’s retreating army on its right flank. A flurry of telegrams followed in the next 48 hours from Halleck and Secretary of War Stanton to commanders in West Virginia with a simple message: pursue Lee.

Kelley acted promptly and pulled his infantry from guarding railroads and left Clarksburg on July 6 with 4,500 men. On the same day Kelley ordered Averell and his cavalry from the Cheat Mountain area, where they had gone to investigate a Confederate raid on Beverly, to Martinsburg to join in the hunt for Lee.

Kelley made good time in the first 100 miles or so from Clarksburg east to Cumberland. But here the advance bogged down, slowed by destroyed railroad bridges and damage to the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal. Downed telegraph lines interrupted communications. Kelley did not connect with Averell. Lee made good his escape from the Gettysburg Campaign.

The failure of Kelley to bring his forces to bear against Lee did not sit well with armchair generals in the state legislature in Wheeling. They criticized Kelley’s leadership and mild treatment of Confederate sympathizers. Kelley staffer David Hunter Strother, a journalist and artist with the pen name Porte Crayon, noted that Gov. Arthur I. Boreman thought that Kelley’s actions were too timid towards the rebels.

A group of legislators charged Kelley with being under the influence of Copperheads, a growing faction of Northern Democrats opposed to the war, and petitioned President Abraham Lincoln to remove the general.

Strother reported in September 1863, “A paper signed by forty-some-odd-members of the Legislature was presented to the President, who, on looking at it, replied ‘Gentlemen, no complaints of General Kelley have reached me through the War Department. This seems a political move. I therefore decline considering it.’ The ground of discontent with the General is his liberal policy toward the disaffected people of the country.”

Kelley focused on his challenging job: Protect 400 miles of strategic B&O rails and more than 24,000 square miles of rugged mountainous territory, a third of it populated by Confederate sympathizers.

During the fall and early winter of 1863, Kelley executed a series of raids to protect loyal people and infrastructure with mixed success. On November 16, he moved the Department of West Virginia headquarters to Cumberland to better protect the B&O. From here, he and Averell planned a raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.

On December 8, Averell left New Creek with a column of 2,500 mounted soldiers. Kelley masked Averell’s movement by sending brigades from the Shenandoah to the Kanawha valleys across West Virginia into western Virginia. The diversion worked. Averell’s column arrived at Salem, Va., on December 16. The men destroyed a significant amount of supplies and tore up tracks before leaving. Averell returned to safety on December 25. Kelley wrote Gov. Boreman, “This is undoubtedly one of the most hazardous, important and successful raids since the commencement of the war.”

In the end, Kelley’s successes did not overcome the narrative that he was soft on Confederates and had let too many valuable supplies fall into enemy hands. In February 1864, Kelley told Strother he expected to be replaced by one of 14 major generals who were without assignment. This prediction came true on March 12, 1864, when Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel relieved Kelley as Commander of the Department of West Virginia.

At 10 a.m., Kelley presented his staff to Sigel. Assistant Surgeon Alexander Neil of the 12th West Virginia Infantry was there, and wrote to his parents that Kelley “looked pale and melancholy.”

Neil continued, “We will pass from under the fatherly care of Genl. Kelley, who has treated us kindly, to ‘fight mit Sigel.’” He stated the belief that “Kelley allows the Rebels to escape and get away when he might overtake and defeat them. Kelley is referred to as ‘Rebel Quartermaster.’ This title is due to the numerous wagon trains traveling between New Creek and Petersburg that were attacked. It is estimated that the loss equaled one million dollars plus the loss of soldiers and moral effect.”

Neil added, “the Genl. is as brave, active, resolute, and sagacious an officer as there is in the service and that he has only been unfortunate.”

Saving Cumberland, facing partisan rangers

of Washington, D.C. Author’s collection.

Kelley did not remain idle for long. On May 6, 1864, Secretary of War Stanton ordered him to command troops guarding the B&O between Monocacy and Wheeling.

This assignment set in motion Kelley’s final success as a soldier—and a final humiliation.

Fears for the safety of Cumberland increased dramatically after Confederate Brig. Gen. John McCausland ordered his troops to torch Chambersburg, Pa., on July 30, 1864. Word that “Town Burner” McCausland had withdrawn through Hancock and may be headed to Cumberland came to Kelley’s attention. He immediately dispatched cavalry to gather intelligence and hastily organized a defense of the city.

Kelley positioned six cannon on the eastern slope of a hill overlooking the National Road, the expected avenue of approach for McCausland’s cavalry. They included four guns from Battery L of the 1st Illinois and two from Battery B of the 1st Maryland light artilleries. Supporting the guns was a ragtag force consisting of inexperienced 100-day Ohio National Guardsman, four companies of the 11th West Virginia Infantry, one company of the 6th West Virginia Infantry, the 2nd Maryland Infantry Potomac Home Brigade, and 200 local men.

McCausland and his men arrived the next day. An artillery duel erupted at 3 p.m. and continued until the Confederates withdrew five hours later. The engagement went down in history as the Battle of Folck’s Mill.

Three days later, on August 4, McCausland attacked Union forces at nearby New Creek. Kelley dispatched soldiers commanded of Maj. James L. Simpson of the 11th West Virginia Infantry to confront them. Simpson’s boys tore into and put the rebels to flight.

Kelley saved Cumberland, New Creek, the B&O Railroad and the C&O Canal. He prevented the destruction of valuable government and railroad property. He received a brevet promotion to major general for his efforts.

Danger remained omnipresent as partisan bands roamed the region. They included McNeill’s Rangers, which had successfully attacked railroads and wagon trains. The leader of this band, Capt. John Hanson “Hanse” McNeill, suffered a wound in an Oct. 3, 1864, skirmish near Mount Jackson, Va., and succumbed to its effects a month later. His son, Jesse, assumed command. Sensing the days of the Confederacy were numbered, young McNeill set his sights on seeking revenge against the man he held responsible for the death of his father—Kelley.

McNeill developed a plan based on intelligence from a successful scouting mission into Cumberland, and hand-picked 60 men with strong mounts to execute the raid.

On the cold and snowy night of Feb. 20-21, 1865, McNeill and his men, dressed in blue overcoats, giving them the appearance of a Union patrol, entered Cumberland. They rode up Baltimore Street and halted in front of two hotels. One detachment of six men went into the Barnum House and captured Kelley and Assistant Adjutant General Thayer Melvin. They were given time to dress before being hustled out and into the street. Another six-man detachment entered the Revere House and captured Maj. Gen. George Crook.

Meanwhile, other Rangers disabled telegraph lines and confiscated horses, including Kelley’s trusty Philippi, from a nearby stable. McNeill’s boys saddled up their prisoners and rode down the towpath of the C&O Canal. Encountering a Union patrol, McNeill convinced them he and his men were out to repel Confederates. The federals believed him.

McNeill’s Rangers rode calmly away with their prize and crossed the Potomac River at Wylie Ford. Then they picked up the pace, knowing that the brazen kidnapping would soon be discovered. Before long, Union troopers were on their tail, but McNeill’s men fought them off and successfully carried their captives over the mountains into the Shenandoah Valley and on to a train bound for Richmond.

That night in Cumberland’s Opera House, singer Mary Bruce performed. She was the daughter of Col. Robert Bruce, commander of the 2nd Infantry Potomac Home Brigade, and Kelley’s girlfriend. She sang a popular song with the line “he kissed me when he left.” As soon as the words passed her lips, a man in the audience yelled out, “the hell he did, McNeill wouldn’t let him!” She ran off the stage crying.

The embarrassing capture of two generals drew criticism through the chain of command up to and including Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Paroled and exchanged on March 23, 1865, Kelley resigned on June 1, 1865.

Epilogue

On Aug. 16, 1865, Kelley married Mary at Cumberland’s Emmanuel Episcopal Church. He accepted a federal job with the Internal Revenue Service and worked there until 1873. During this period he helped create the West Virginia Department of Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) and the Society of the Army of West Virginia.

Kelley went on to hold two federally-appointed positions. He served as the first Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation in Arkansas (Hot Springs National Park) from 1877 to 1882. He cleaned up and closed the land to squatters, built bathhouses, and championed the cause of allowing the poor to take advantage of the healthy waters free of charge. In 1883, he became a U.S. Pension Bureau claims examiner and moved to Washington. He resigned in 1888.

Three years later, at 8 p.m. on July 16, 1891, Kelley drew his last breath on his farm, Swan Meadow, near Oakland, Md. He was 84.

The old warrior, dressed in a major general’s uniform adorned with badges of various organizations, was placed in a casket and escorted by his local G.A.R. post from his farm to St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Oakland two days later. When the church doors closed that night 600 people had passed the general’s guarded casket.

The following day, the railroad that Kelley had protected during the war carried him to his final resting place. At 9 a.m., the flag-draped casket was transported to the railroad depot and placed upon a special train to Washington, with stops in Piedmont, Keyser, Cumberland and Martinsburg for the public to pay their last respects. The train arrived in the District of Columbia at 4:20 p.m. and about 40 minutes later the casket containing Kelley’s body was placed on a caisson and moved to the Grand Army Hall. Pallbearers included generals William S. Rosecrans and Joseph J. Reynolds, and former staff officers.

At 6 p.m., a procession accompanied the caisson, draped in black and drawn by four bay horses, for the final leg of the journey to Arlington National Cemetery. Kelley’s casket was covered with flower wreaths upon which rested his sword. A graveside service concluded with a rifle volley and playing of taps.

Kelley never commanded soldiers in a momentous battle. He was a good and honest man who did his job. He protected a very strategic railroad. He performed every task assigned to him. He did not treat citizens harshly. He understood that after the war everyone had to live together. He loved horses, both the four-legged kind and iron.

References: Frothingham, Sketch of the Life of Brig. Gen. B.F. Kelley; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; Benjamin F. Kelley pension file; Wheeling Intelligencer, 1861 to 1891; Lang, Loyal West Virginia, 1861 to 1865; Kelley’s letters, scrapbook, and documents, author’s collection; Haselberger, Confederate Retaliation: McCausland’s 1864 Raid; Delauter, McNeill’s Rangers; Eby, ed., A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War: The diaries of David Hunter Strother.

Richard A. Wolfe is President of the Rich Mountain Battlefield Foundation. He is a retired Marine Corps officer and information technology manager. He collects West Virginia Civil War photographs.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.