By Kurt Luther

During the Civil War years, the Washington, D.C., area was surrounded by a ring of 68 US Army forts known today as the Civil War Defenses of Washington. As a resident of the area, I have enjoyed exploring the surviving remnants of these defenses, which range from well-preserved and interpreted sites like Alexandria, Virginia’s Fort Ward Museum & Historic Site, to many others that reveal no trace of the conflict aside from leveled terrain and perhaps a historical marker.

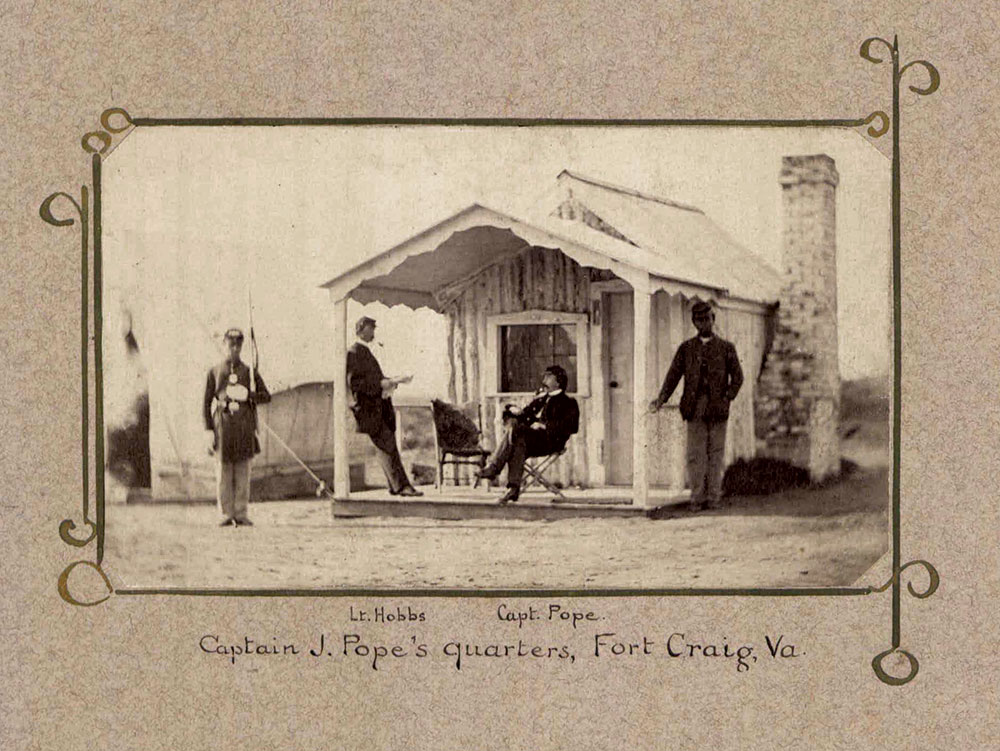

However, back in the 1860s, some of these same fortifications were extensively photographed, providing valuable material for Civil War photo sleuthing. For example, in the Spring 2020 edition of Military Images, I researched a Library of Congress collection that led to correcting a misidentified photo of officers gathered on a porch at Fort C.F. Smith in Arlington, Va.

Beyond the forts themselves, I was curious about the people for whom they were named. For the larger sites like Fort C.F. Smith and Fort Ward, information and photos about their namesakes (Maj. Gen. Charles Ferguson Smith and Cmdr. James H. Ward, respectively) are readily available. For the smaller, more obscure ones, it is often difficult to find images of the individuals whose lives they honor.

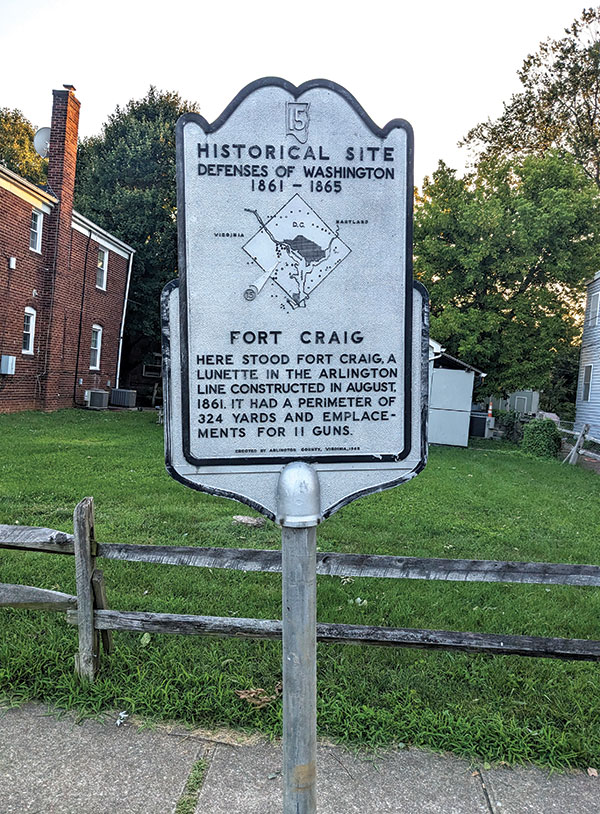

One such example near my home in Arlington is Fort Craig. Today, the site is located at the crest of a residential street within sight of the National Cemetery. No trace of the fort remains, but I have walked by the historical marker installed on the sidewalk in 1965 many times. It reads:

Here stood Fort Craig, a lunette in the Arlington Line constructed in August 1861. It had a perimeter of 324 yards and emplacements for 11 guns.

During the Civil War, Fort Craig protected Washington from an enemy approach along the Columbia Turnpike. Union troops continuously occupied the fort from December 1861 through the end of the war, until its removal in June 1865. Most units were New England heavy artillery companies rotating in for a month at a time, according to Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington, by Benjamin Franklin Cooling III and Walton H. Owen II.

Who was Fort Craig named for? The historical marker gives no hint, but a little research revealed the answer. The Arlington Historical Society’s website hosts complete archives of its Arlington Historical Magazine, published since 1957, on its website as downloadable PDFs. An article published in the October 1960 issue by C.B. Rose, Jr., titled, “Civil War Forts in Arlington,” notes that Fort Craig was named for “Lt. Presley O. Craig of Massachusetts, killed at Bull Run, July 21, 1861.” The credited source is General Order 18, A.G.O. (Adjutant General’s Office), Sept. 30, 1861, which named each of the 32 D.C.-area forts in existence at that time, many for Union soldiers killed in action like Lt. Craig.

“Fortifications of the Civil War Defenses of Washington were often named to honor fallen officers,” says Bryan Cheeseboro, a Civil War photo historian and former board member of the non-profit organization The Alliance to Preserve Civil War Defenses of Washington. “Given the time the forts were built, most forts so named were for casualties from early in the war, including Fort Ellsworth, Fort Baker, Fort Slocum, and Fort Craig.”

I sought to learn more about Lt. Craig and perhaps find a photo of him. Using the American Civil War Research Database (HDS), I confirmed the Arlington Historical Magazine article’s claim that he had died at First Bull Run. HDS also noted that Craig was born in Massachusetts and commissioned as a second lieutenant into the 2nd U.S. Artillery in 1857. No photos or other information were included in the profile, but one of the listed sources was Francis Bernard Heitman’s Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army.

Published in 1903, this reference work included an alphabetical listing of all commissioned officers of the U.S. Army from 1789 to 1903, including full names, service records, awards and other pertinent details. I found a free, digitized copy on Google Books, and a search for Craig’s name yielded results on page 333. The entry stated that Presley O. Craig was a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy from July 1, 1853, to December 31, 1854, followed by his commissioning on May 14, 1857. The reason behind the nearly 3.5-year gap was unclear.

I started a fresh Google search for Presley Craig and discovered another period source that shed more light on his early years. A digitized edition of The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine for 1911-1912 states that Lt. Craig studied at Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School in 1852. This period of study must have directly preceded Craig’s time at West Point.

Digging further into my Google search results, I found a biographical sketch of Lt. Presley Craig published in The Fallen Brave: A Biographical Memorial of the American Officers who Have Given Their Lives for the Preservation of the Union, published in 1861 and digitized on Google Books. Craig’s profile was penned by his brother, John Neville Craig, who joined the Union Army as a captain of volunteers in 1862, and continued his service in the Regulars after the Civil War.

The sketch reveals that both Craig brothers followed in a family tradition of distinguished military service. Their grandfather, Maj. Isaac Craig, was an Irish immigrant who joined the Colonial Marines and fought in the American Revolution; his wife Amelia was the daughter of Col. John Neville, commander of Fort Pitt and, later, the 4th Virginia Regiment.

Their father, Henry Knox Craig, was a career Army officer who, like his son Presley, started out in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He served in the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, earning promotion to colonel and heading up the Army’s Ordnance Bureau before his retirement in 1863.

According to John’s biography, Presley Oldham Craig was born in December 1834 at the Watertown Arsenal in Massachusetts. Surprisingly, it says nothing of his time at either Harvard or West Point, instead skipping directly to his commissioning in 1857. Lieutenant Craig was about 23 years old when he began his military service stationed at Fort Hamilton in New York. By all accounts, he found the assignment boring, but his requests for transfer to the field were declined.

In the summer of 1860, Craig’s ambitions were further waylaid when he was thrown from a vehicle, severely injuring his left foot. Two months passed and the injury had not improved, so he sought treatment in Washington. A year later, there was still “scarcely perceptible advancement in his condition,” leaving Craig “unable to walk without the aid of crutches.”

Meanwhile, civil war had broken out across the country, and armies were gathering just outside the city. Being so close to the action, yet out of action, we can imagine Lt. Craig’s frustration reaching a tipping point after years of struggle and a legacy of military achievement to live up to. His brother-in-law Capt. Henry J. Hunt, the Army of the Potomac’s future Chief of Artillery who had married Presley’s sister Mary, presently commanded the 2nd Artillery’s Battery M. The battery was about to depart Washington for Bull Run when one of its officers fell ill, and Lt. Craig, who still walked with a cane, seized his opportunity.

Captain Hunt, in his after-action report eventually published in the Official Records, recounted what happened next:

First Lieut. Presley O. Craig, Second Artillery, on sick leave on account of a badly-sprained foot, which prevented his marching with his own company, having heard of the sickness of my second lieutenant, volunteered for the performance of the duties, and joined the battery the day before it left Washington. He was constantly and actively employed during the night preceding and on the day of the battle, and his services were very valuable. When the enemy appeared he exerted himself in perfecting the preparations to receive him, and conducted himself with the greatest gallantry when the onset was made. He fell early in the action, whilst in the active discharge of his duty, receiving a shot in the forehead, and dying in a few minutes afterwards. This was the only casualty in the battery.

John Neville Craig’s sketch provides a complementary and tragic perspective of the day from Presley himself. On the morning of battle, Presley “hurriedly penciled and dispatched the following note, which only reached its destination after his lifeless body had been borne across the paternal threshold”:

6 a.m., Sunday.

Dear Father,—

We are to have a grand battle this morning. The movement has been delayed by the troops not getting in position. I was out from before sundown til three this morning with a section, but feel all right. We have been put in the reserve, but will be called on soon. We are to turn the left, if we can. I have not time to write more. Love to all.

Your affectionate son,

Presley O. Craig

Lieutenant Craig’s body was transported first to Alexandria. He was buried in the family plot in Oak Hill Cemetery, in Washington, the city he lived in for years awaiting the chance to prove himself, and that he ultimately gave his life to defend. He rests alongside his parents, his brother and biographer John, and other relatives.

Having learned of Lt. Craig and the story of his sacrifice honored by Fort Craig, I hoped to also find a photo of him. Unfortunately, the Fallen Brave book contained none. Moving on, I searched the other usual suspects for Union officer photos — HDS, the US Army Heritage and Education Center’s (USAHEC) MOLLUS-Mass collection, and my own Civil War Photo Sleuth website — but again came up short.

I also made inquiries with local historians. No one knew of any existing photos of Lt. Craig, but they hoped I could find one. “Understanding the background for the naming of Fort Craig, including a picture of the soldier honored, would be a useful contribution to making Civil War history relevant and entertaining to modern visitors,” Marty Suydam, an Arlington Historical Society board member, told me.

Most of my successes so far in this research project had come from period publications, so I renewed my online searches for anything referencing variations of the name Presley Oldham Craig, focusing on digital book repositories like Google Books and the Internet Archive. The U.S. Army’s Center of Military History website hosts a web-based version of the 1896 publication The Army of the U.S.: Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief, whose chapter on the 2nd Artillery mentions Lt. Craig’s death, but contains no portrait. Lamb’s Biographical Dictionary of the U.S. (1900) contains a portrait of Henry Knox Craig but not his son.

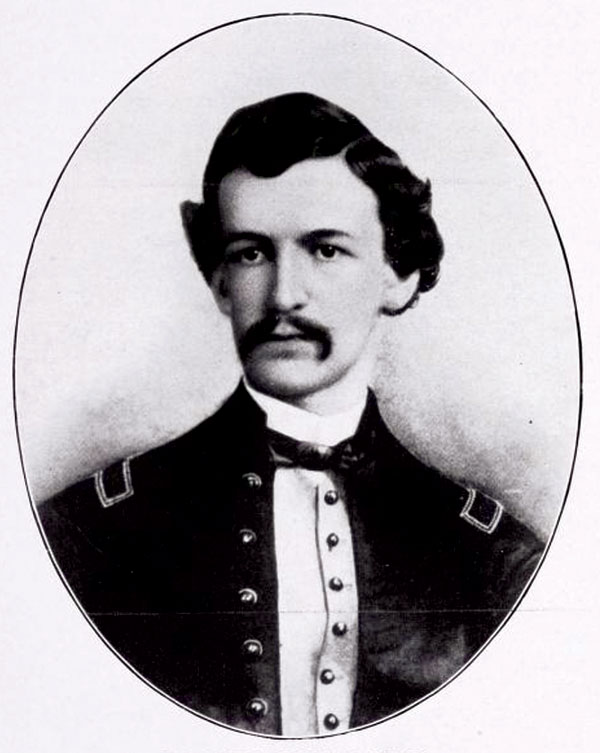

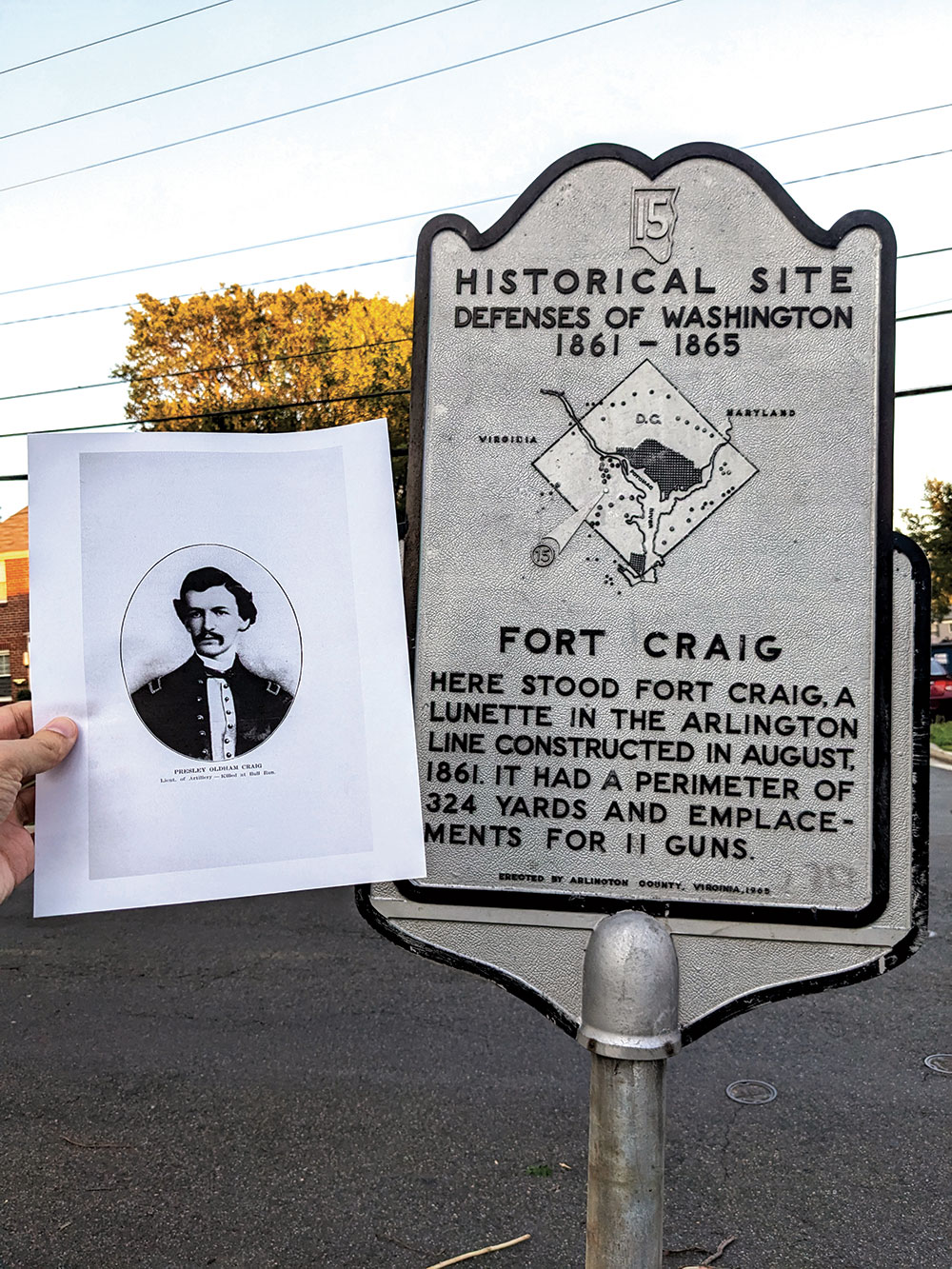

First Lieutenant Presley Oldham Craig. Internet Archive.

A mention of Lt. Craig’s name in a privately published genealogy book digitized on the Internet Archive caught my attention. Memoranda Concerning Some Branches of the Hawkins Family and Connections (1913) was written by John Parker Hawkins, another brother-in-law of Presley. Hawkins, a West Point graduate, married Presley’s sister, Jane, and completed his Civil War service as a brevet major general. Lieutenant Presley Craig is only mentioned a couple of times in Hawkins’ 137-page book, but on page 99, I was thrilled to discover that it includes a wartime portrait of Craig in uniform. Wearing an unbuttoned Union officer’s coat with second lieutenant shoulder straps, along with a mustache and coiffed, dark hair and eyes, Craig looks every inch the brave young officer determined to prove himself on the battlefield.

I printed a copy of Craig’s portrait from the Hawkins book and brought it with me to the former site of Fort Craig. As the sun set behind the historical marker, I wondered if this was the first time the face of Lt. Craig was seen within the boundaries of the fort given his name. I felt a connection to this young officer whose family, like mine, came from Pittsburgh; whose name adorns a historical site in my neighborhood, both of which are largely forgotten today.

Bryan Cheeseboro, the photo historian and former Alliance board member, believes that portraits like this one can help others appreciate this history. “After the war, most of the forts and batteries of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, including Fort Craig, were entirely lost to 20th century growth and development of the D.C. metro area,” he says. “To see the face of Lt. Craig today will help us humanize the war as well as remember the earthworks named in his honor.”

Lieutenant Presley Craig had a fort named after him in 1861, but it may have been more than 50 years before his portrait was finally published, and more than a century after that until I rediscovered it. We still do not have portraits of all of the individuals honored by forts in the Civil War Defenses of Washington. With a bit more photo sleuthing, they will not have to wait much longer.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.