By Ronald S. Coddington

I felt immediately comfortable on meeting Felicity Peck for the first time. Her soft eyes and smile, silver hair and British accent charmed me.

“You’re with Millatree Images,” she noted. I smiled back in acknowledgement.

Millatree and Military became a bit of banter as we came to know each other.

We were not alone. Bruce Jackson, longtime friend of Felicity’s late husband, Herb, stood with us in the foyer of her home in Nashville. I was here in Tennessee’s capital city thanks to Bruce, the official Agent for the Herb Peck Jr. Collection.

The three of us sat down at the round glass table in Felicity’s dining room. Her first words to me after we were seated are forever etched in my memory: “It killed his soul.”

I paused to absorb her words. I glanced at Bruce, who slowly nodded in agreement.

“It” referred to the burglary at the Peck home at 3332 Love Circle in Nashville. On Friday morning, Sept. 29, 1978, an intruder or intruders kicked in the wood and glass kitchen door, entered the house, and made a beeline to Herb’s study. No one was home. Herb went about his normal routine in his office at Vanderbilt University. Felicity had left town for a weekend church retreat in Ohio. Tim, their 13-year-old son, was off at school.

Tim, now 58, recalls his father’s sardonic observation that Felicity “took Jesus away from the house” when she departed that morning.

The devil worked quietly and quickly to steal treasures that Herb, 42, had amassed over years. By the time he returned home for lunch, the burglars had left with items that had long been part of his identity. Missing were three cameras and more than a dozen rifles, shotguns, and revolvers. And a number of Confederate and antebellum images.

Tim left school about 3 o’clock and walked home. As he rounded the curve of Love Circle, he noticed two police cruisers in front of the house. Surprised and puzzled, he made his way through the front door as he did every school day and found his father with an officer. Herb looked worried and unhappy, maybe in shock, but not angry. Tim never saw his father angry.

The thought of strangers violating the sanctity of their home rattled Tim. He recalls his parents setting him at ease by explaining that the burglars were only after the Confederate images and a few guns, not people.

In other words, a surgical strike.

Guns and images

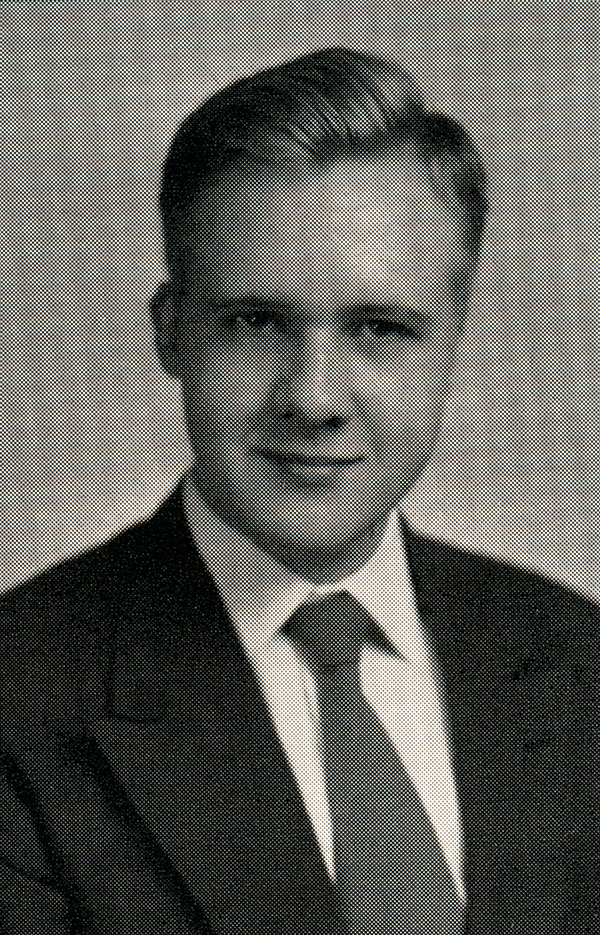

Herbert Jefferson Peck, Jr., entered the world in Nashville in 1936. His first decade of life unfolded against the backdrop of the Great Depression and World War II. During his teens, America and the rest of the globe adjusted and adapted in the wake of atom bombs, communism and authoritarianism.

How these epic events shaped Herb’s life is unclear. But by the time he reached maturity, his larger-than-life character had emerged. Bursting with brilliant wit, a running commentary about any subject under the sun, and a marked inability to conform to societal norms, he became an unstoppable force of nature. There was nothing conventional about Herb. He was the guy who would say anything, anytime. Friends and acquaintances anticipated his every word.

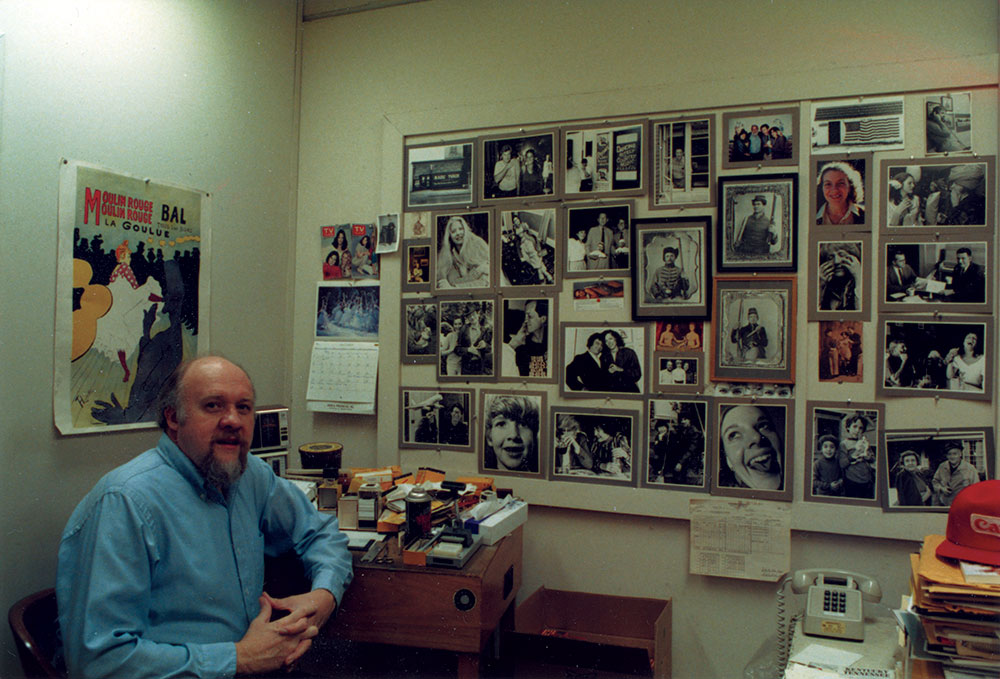

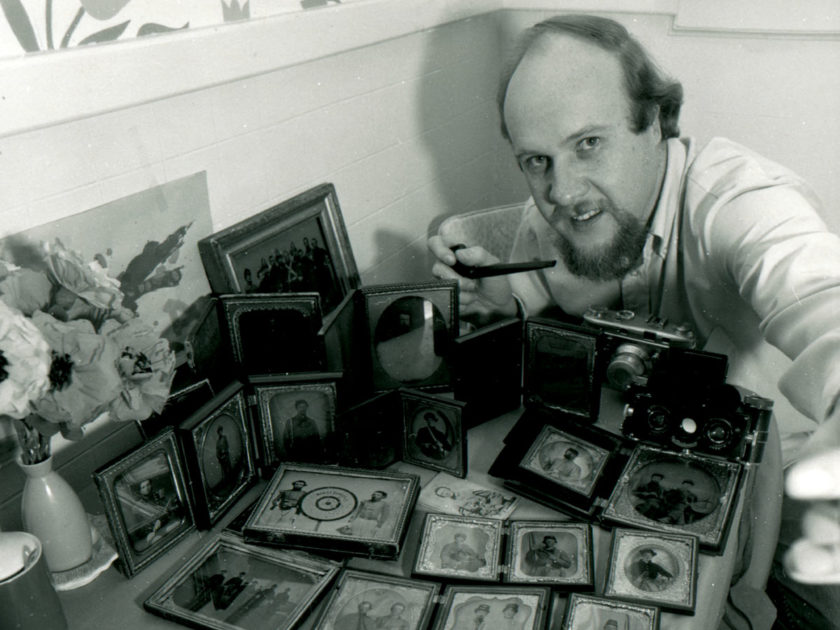

His eccentricities followed him into the U.S. Army (1956-58) and then Vanderbilt, where he enjoyed a long and memorable career as a photographer in the Department of Fine Arts. Dr. F. Hamilton Hazlehurst (1925-2020), who pioneered the Art Chair, initially hired Herb to create slides of art works for professors to use in lectures. The slide library grew to more than 10,000 during Herb’s decades on the job.

Herb became a familiar and popular figure at Vanderbilt, often seen with a Leica camera hanging around his neck, documenting campus life and its notable visitors.

Herb held on to a lot of stuff. A textbook packrat, everything had value to him. Above all, he possessed an unbridled passion for guns. Revolvers. Pistols. Muskets. Rifles. Shotguns. Antique or modern. Guns were an extension of him.

When the Tennessee Gun Collectors Association formed in 1953, Herb became the organization’s youngest charter member at 17.

Herb carried guns almost all the time. Not for protection—he was not paranoid—but for the love of them. Guns in the house. Guns stashed under floorboards in the attic. Guns in the car. Guns everywhere. Later in life, Tim found Herb in the driveway with a weapon. Herb called it as his “car to house gun.” Watching movies on television, whether a Western starring John Wayne, or Clint Eastwood in a Dirty Harry thriller, Herb played with the same guns he viewed on the screen.

He enjoyed shooting them, too. Herb fired guns in a bullet trap in the basement. He cast lead bullets in the newly renovated kitchen. Felicity remembers the unique sound of tapping molds to release the leaden missiles inside.

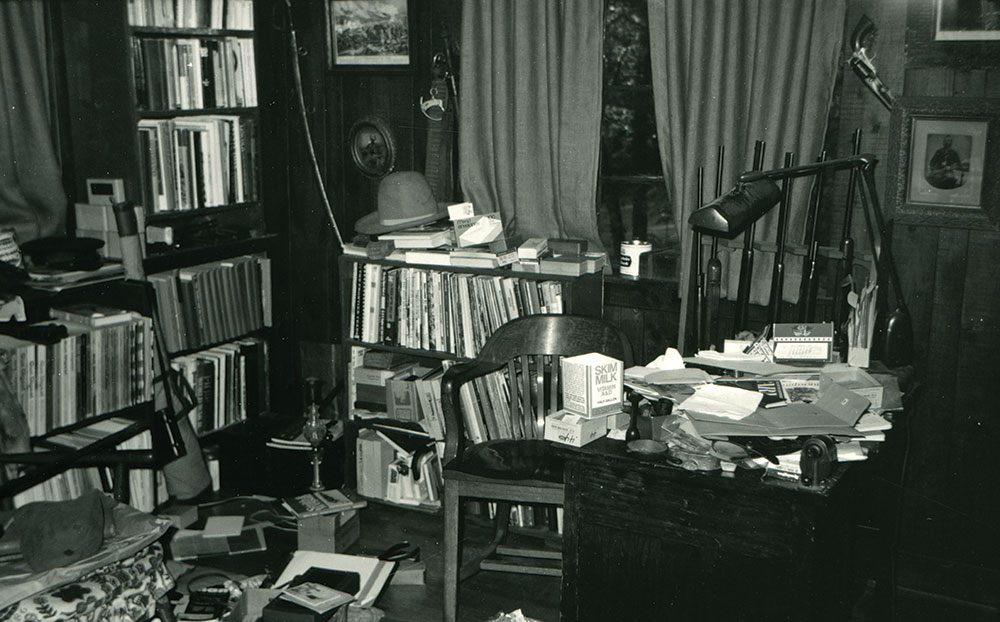

Herb communed with his cherished guns in a study converted from the dining room. Weapons stood guard like steely-eyed soldiers on silent sentry, sometimes found in the most unexpected places. One spot was an old chair reserved for guests. When not in use, it had three cushions stacked on the seat. Between each cushion Herb kept a loaded revolver. Herb’s desk, with a slim drawer across the front and a column of three more down one side, was another unusual location. Beneath the bottom drawer Herb stored three more guns, each protected in soft cases fastened with velcro strips.

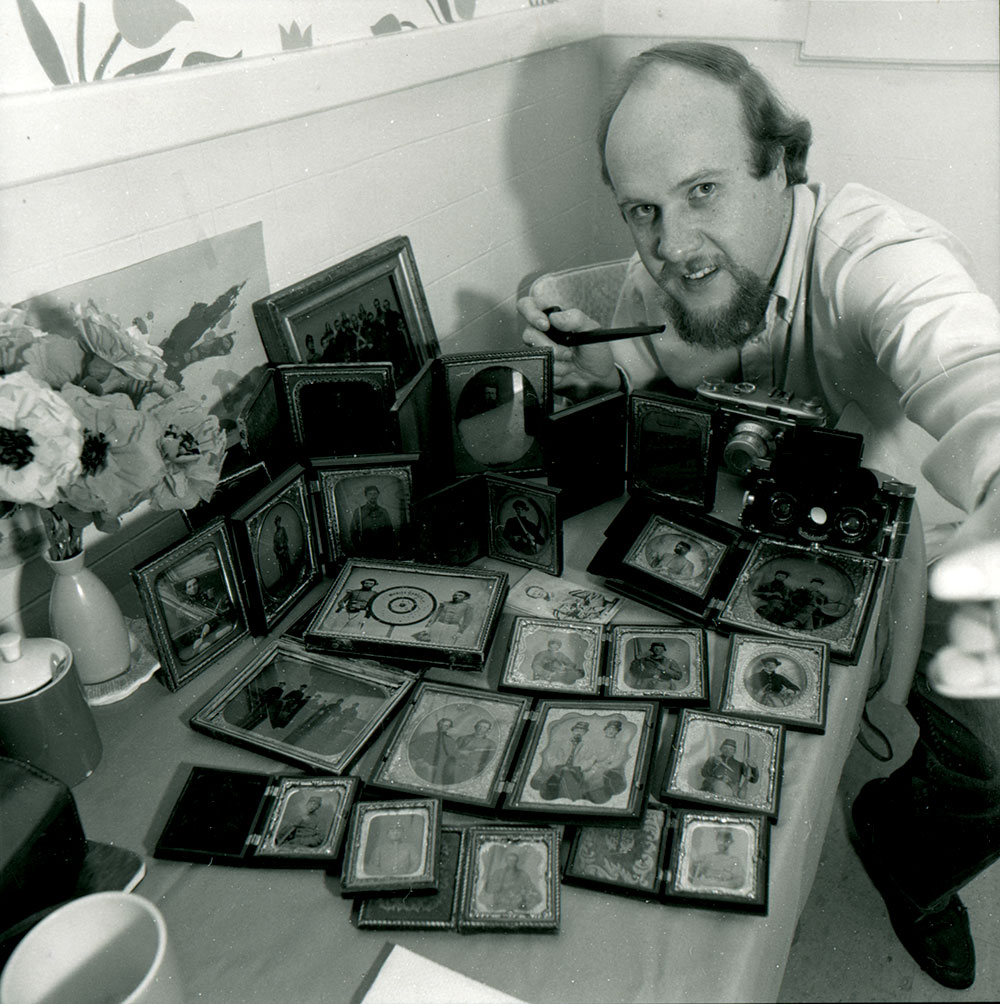

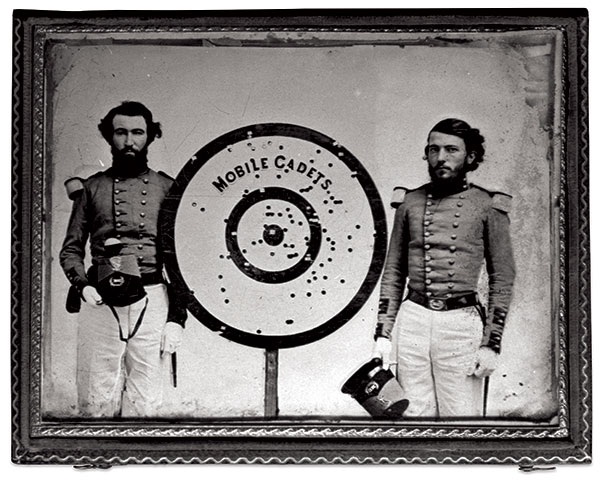

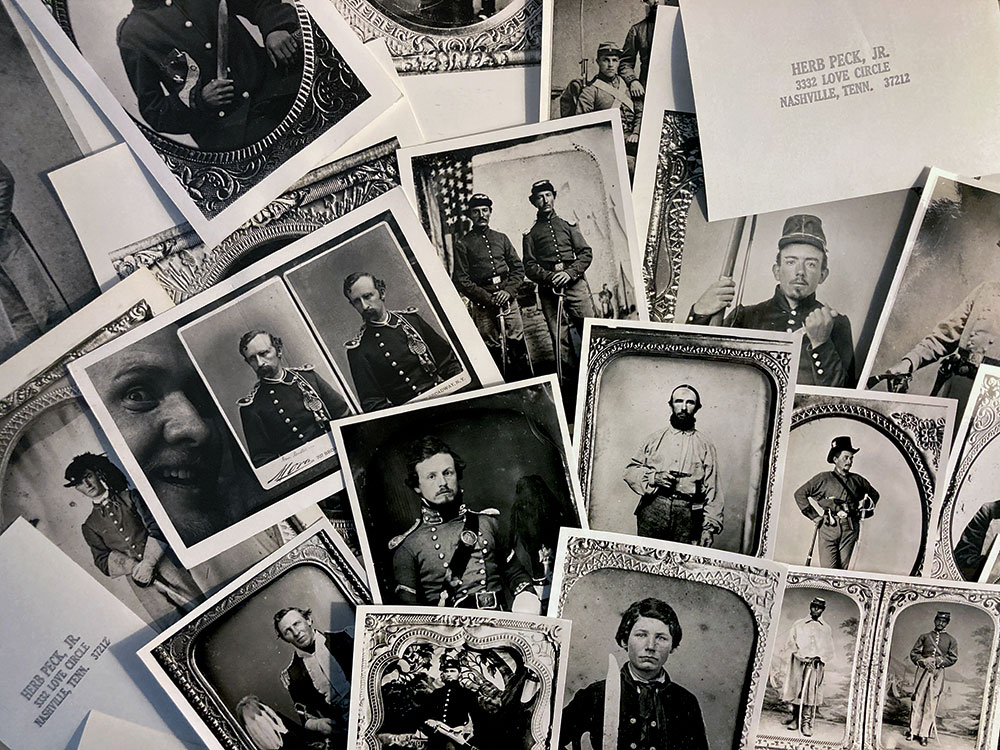

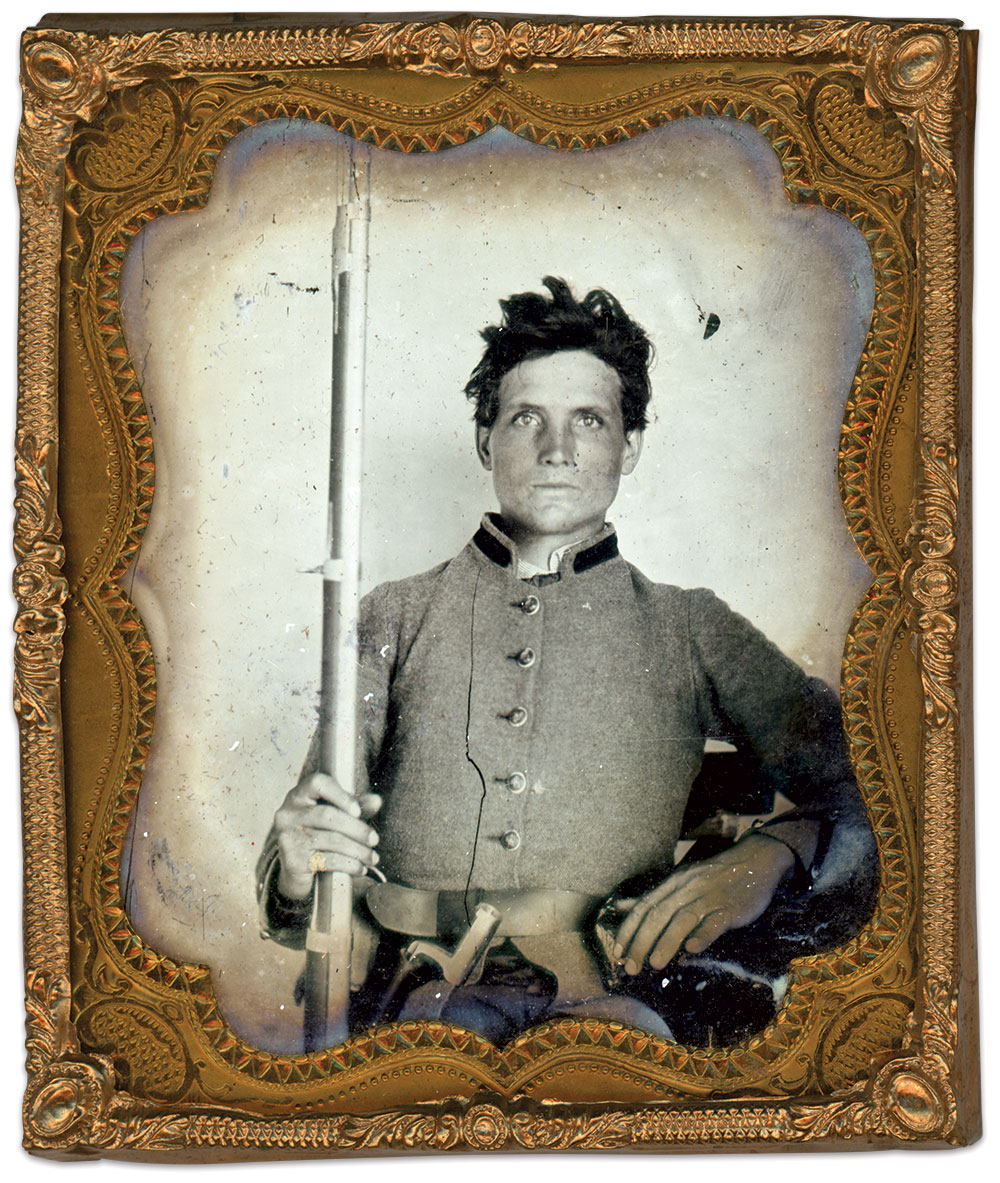

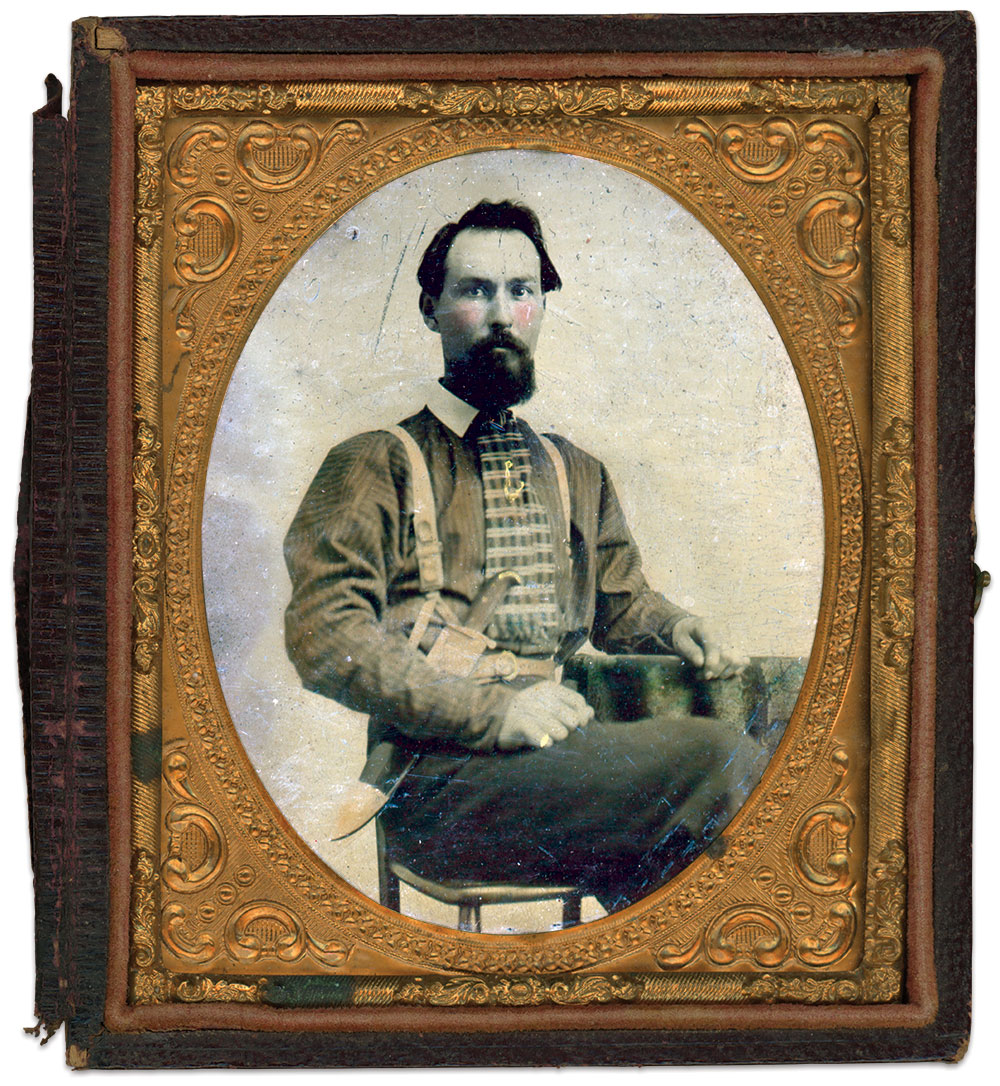

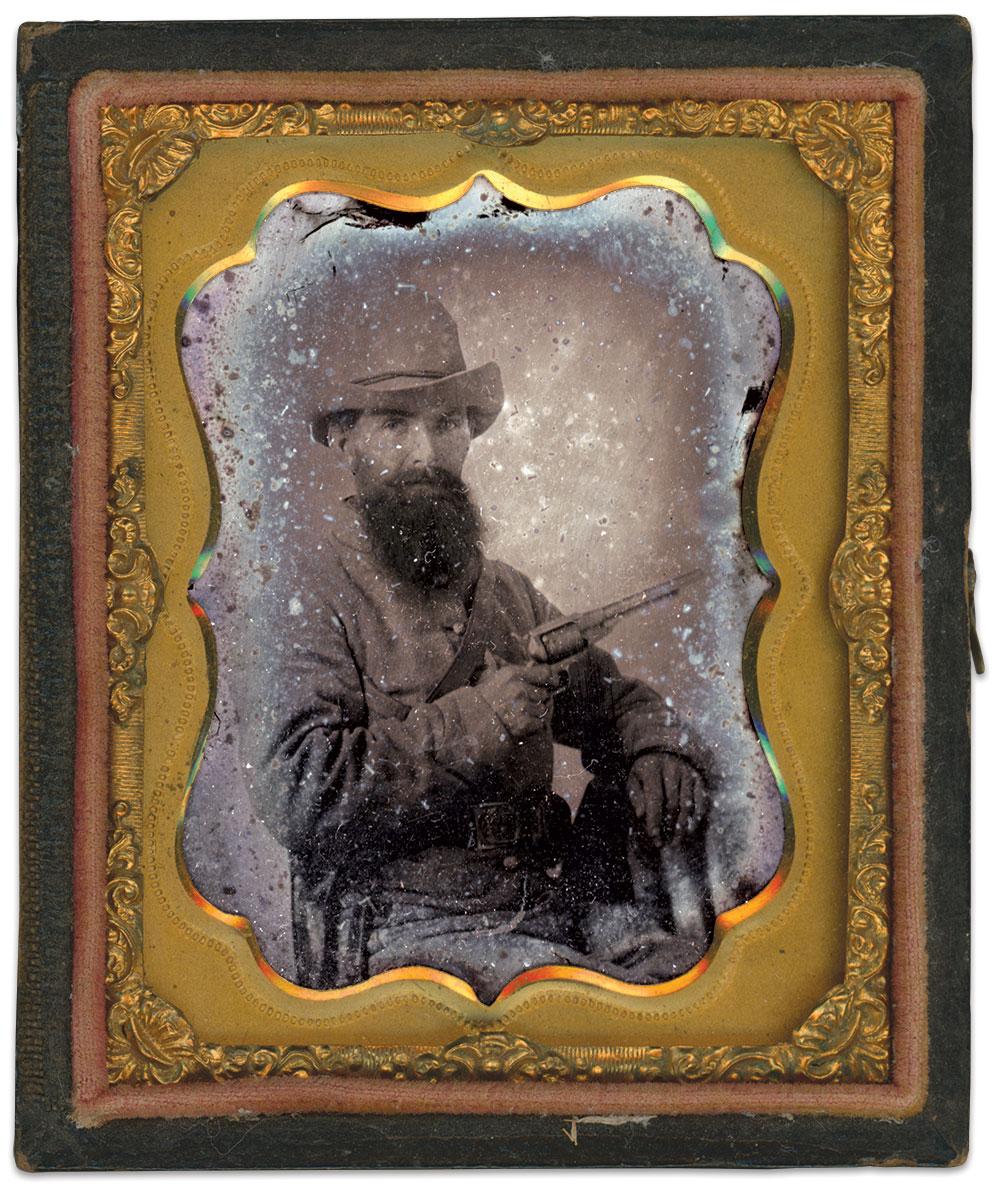

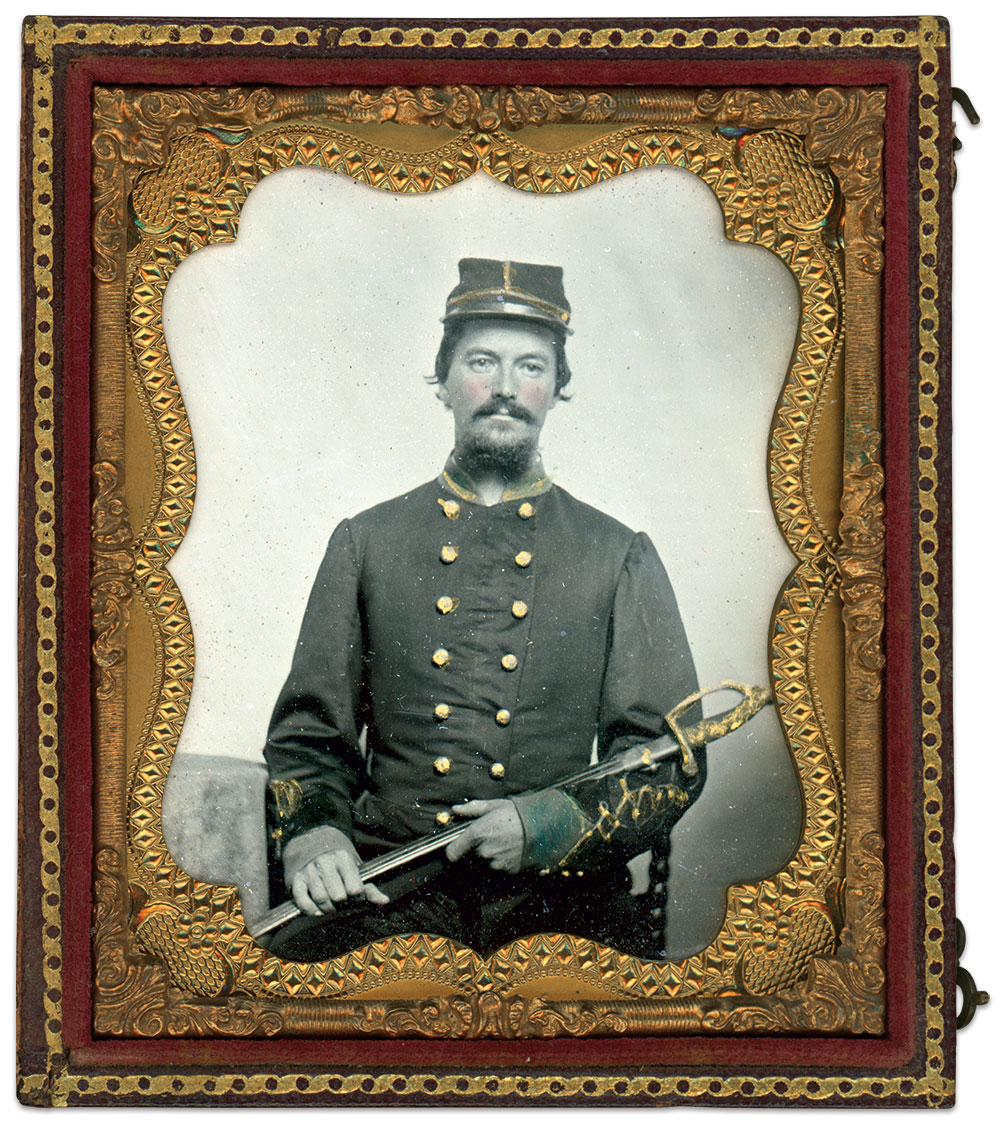

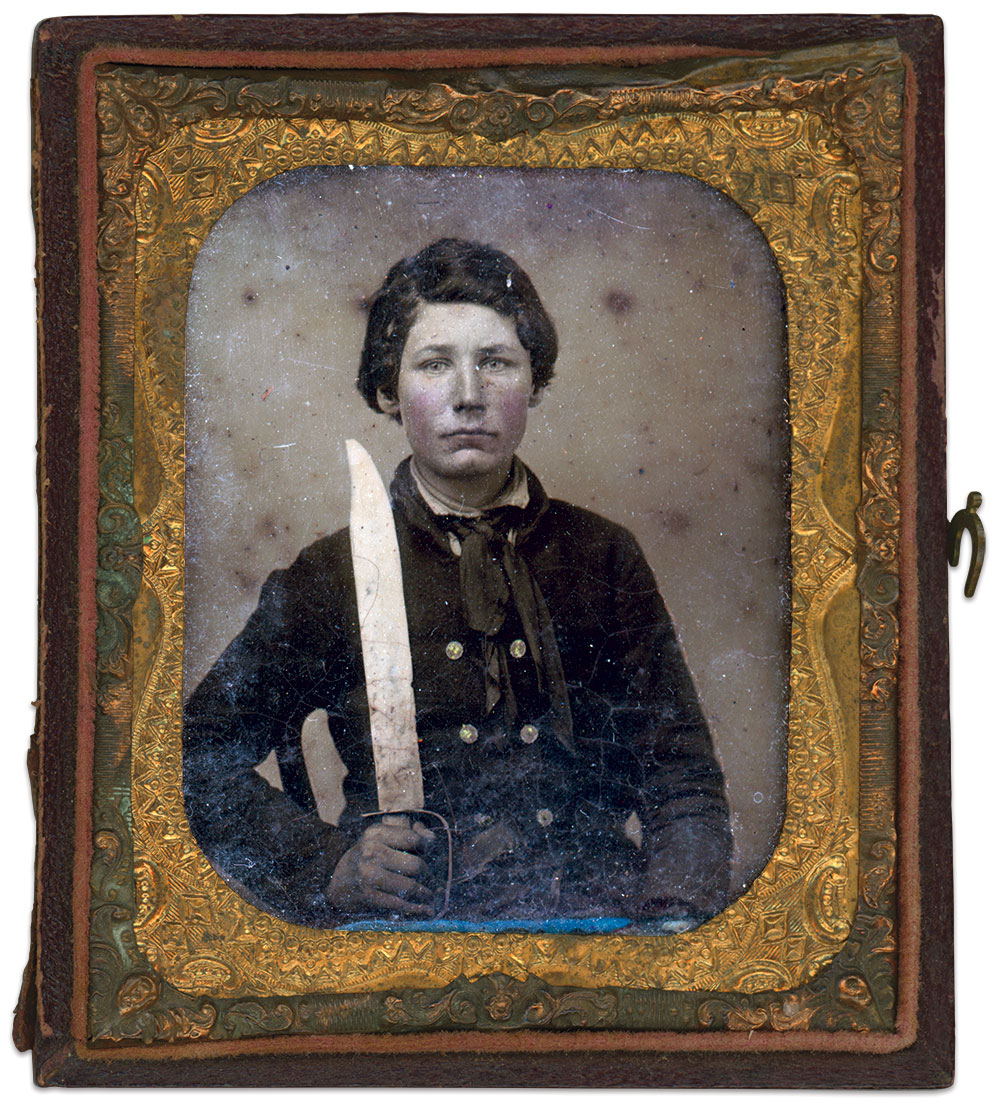

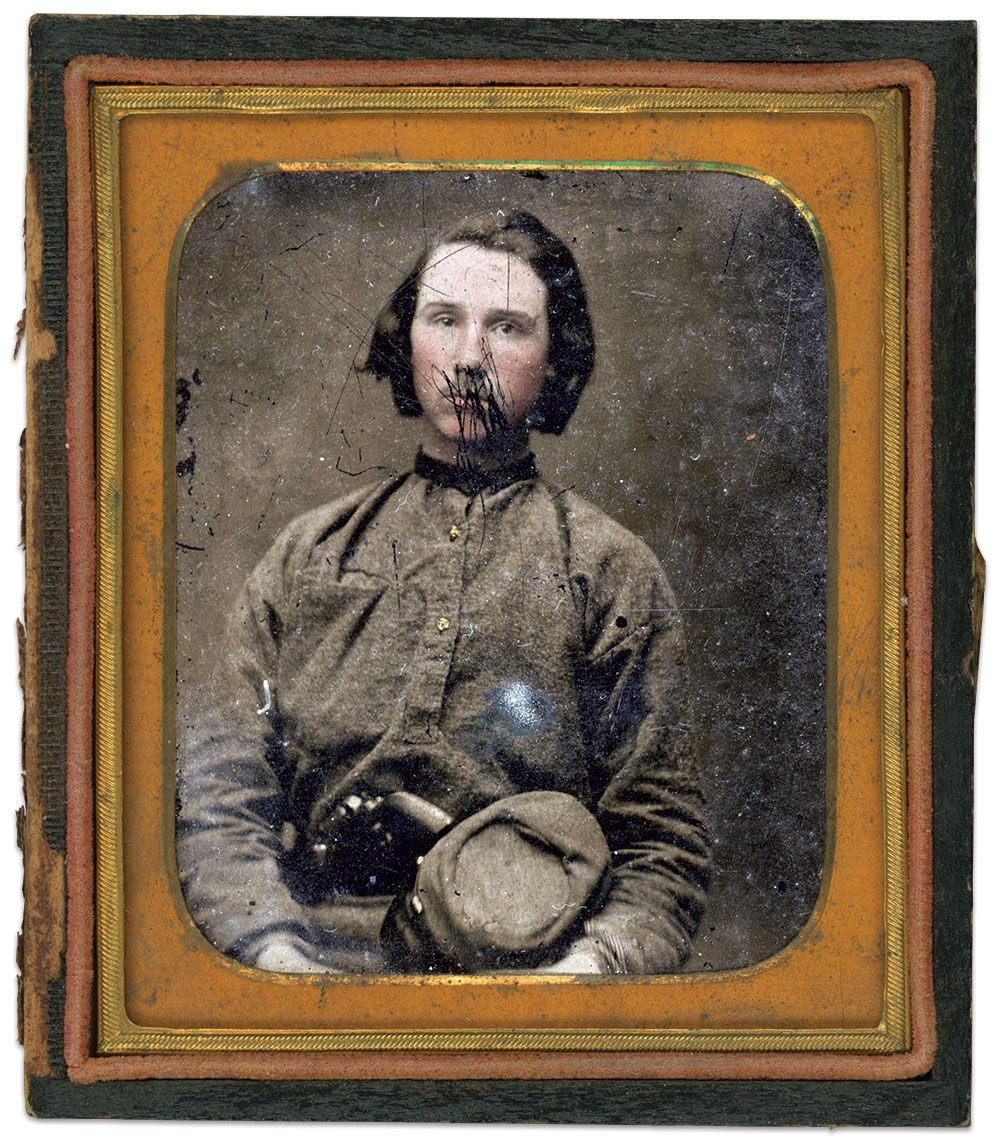

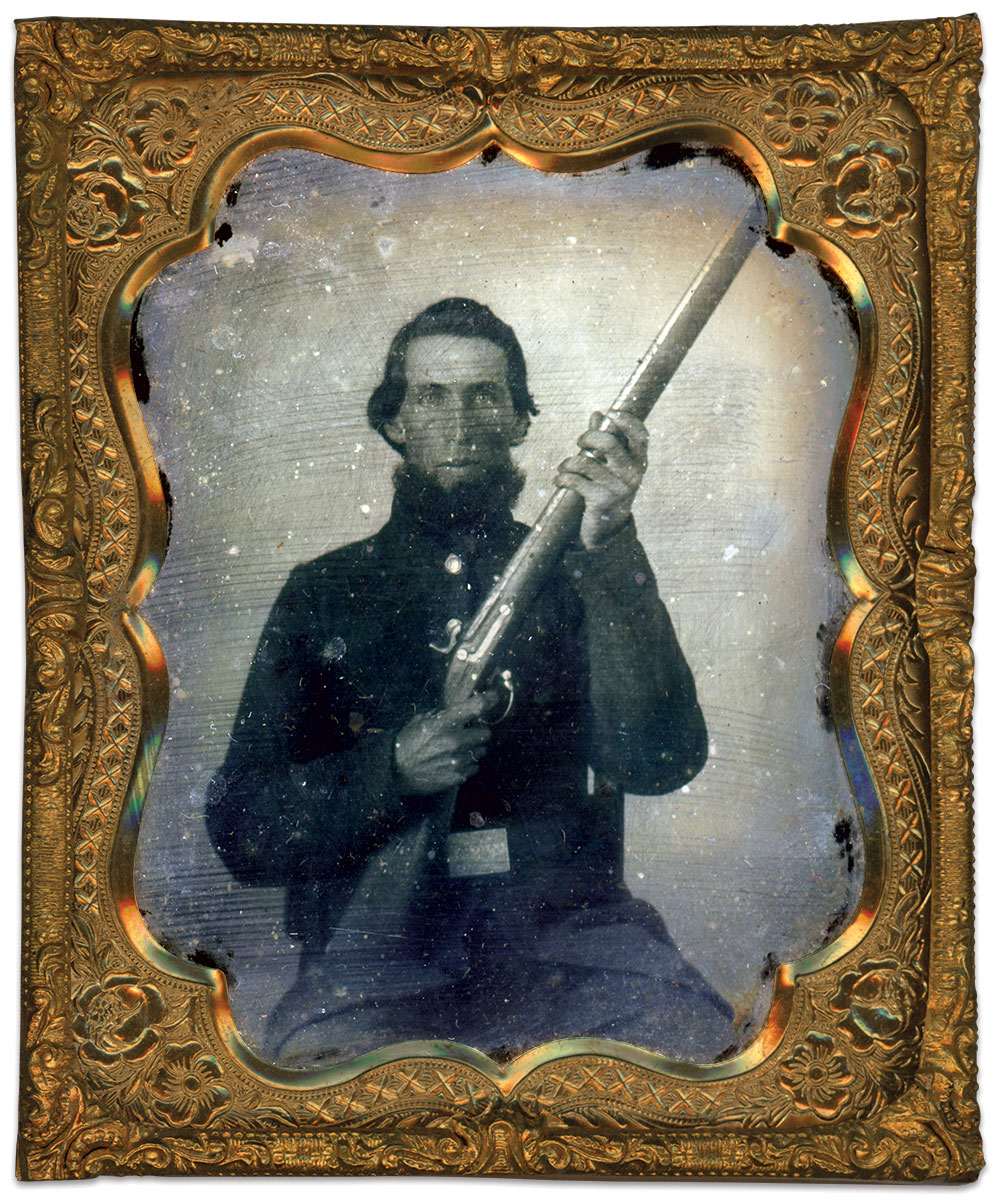

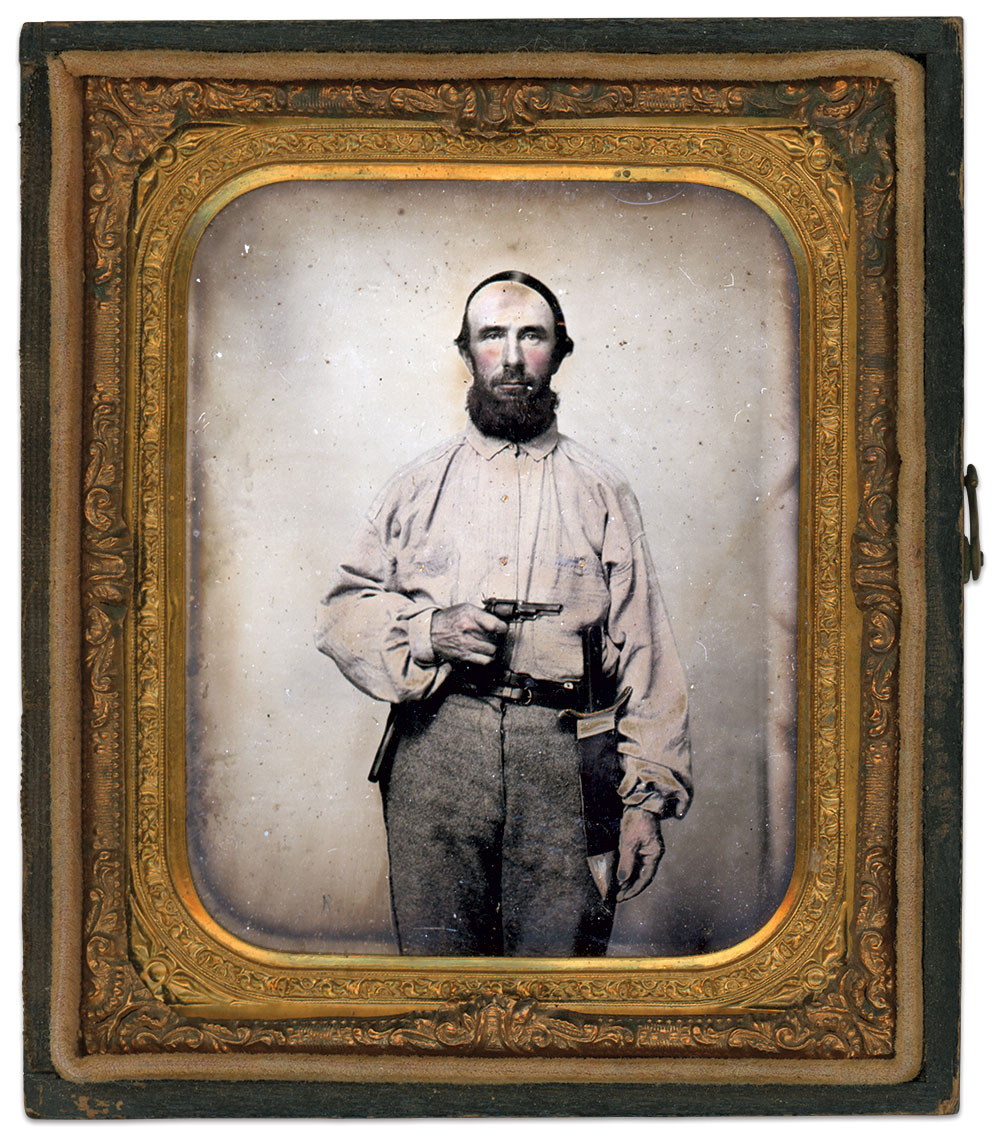

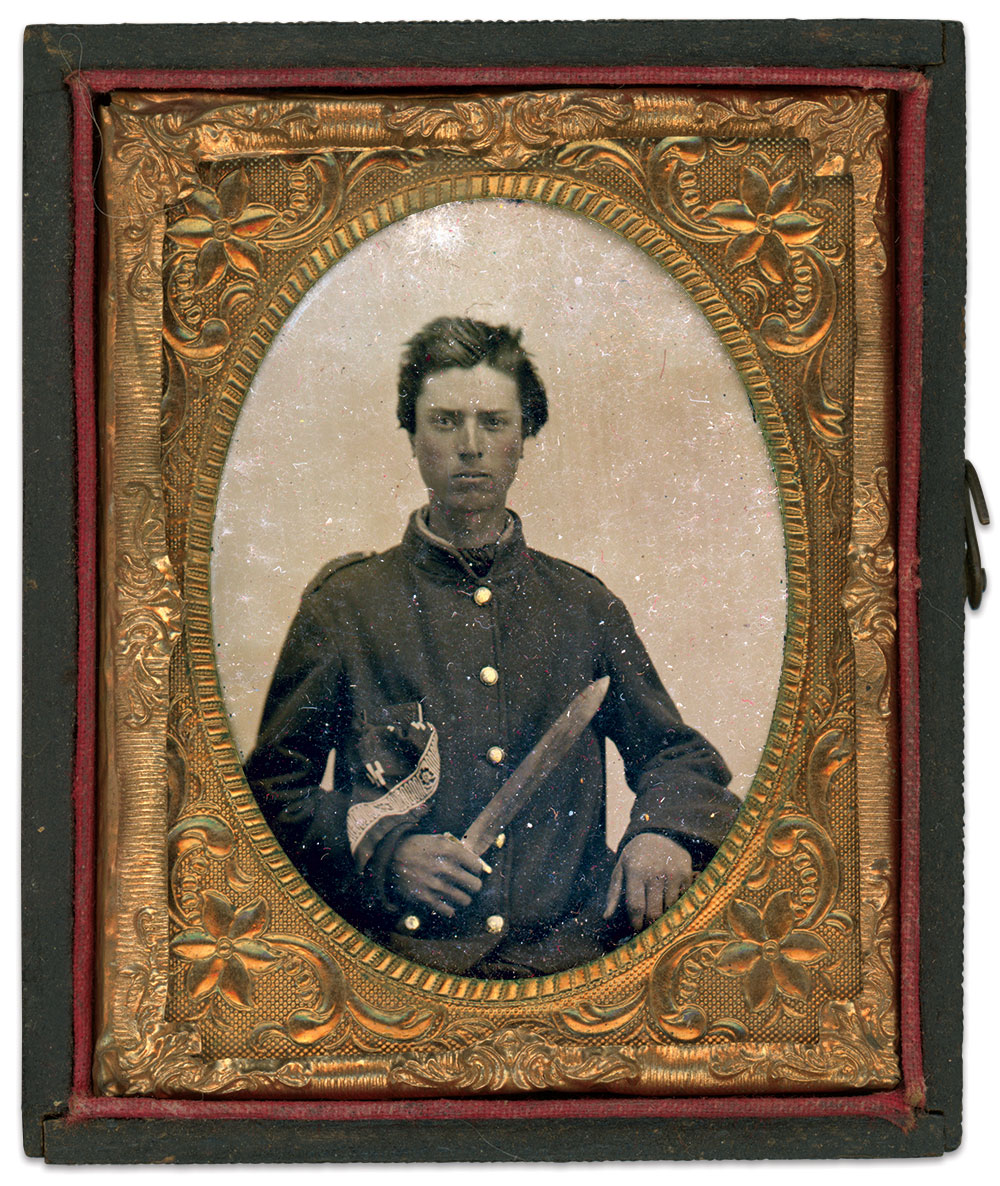

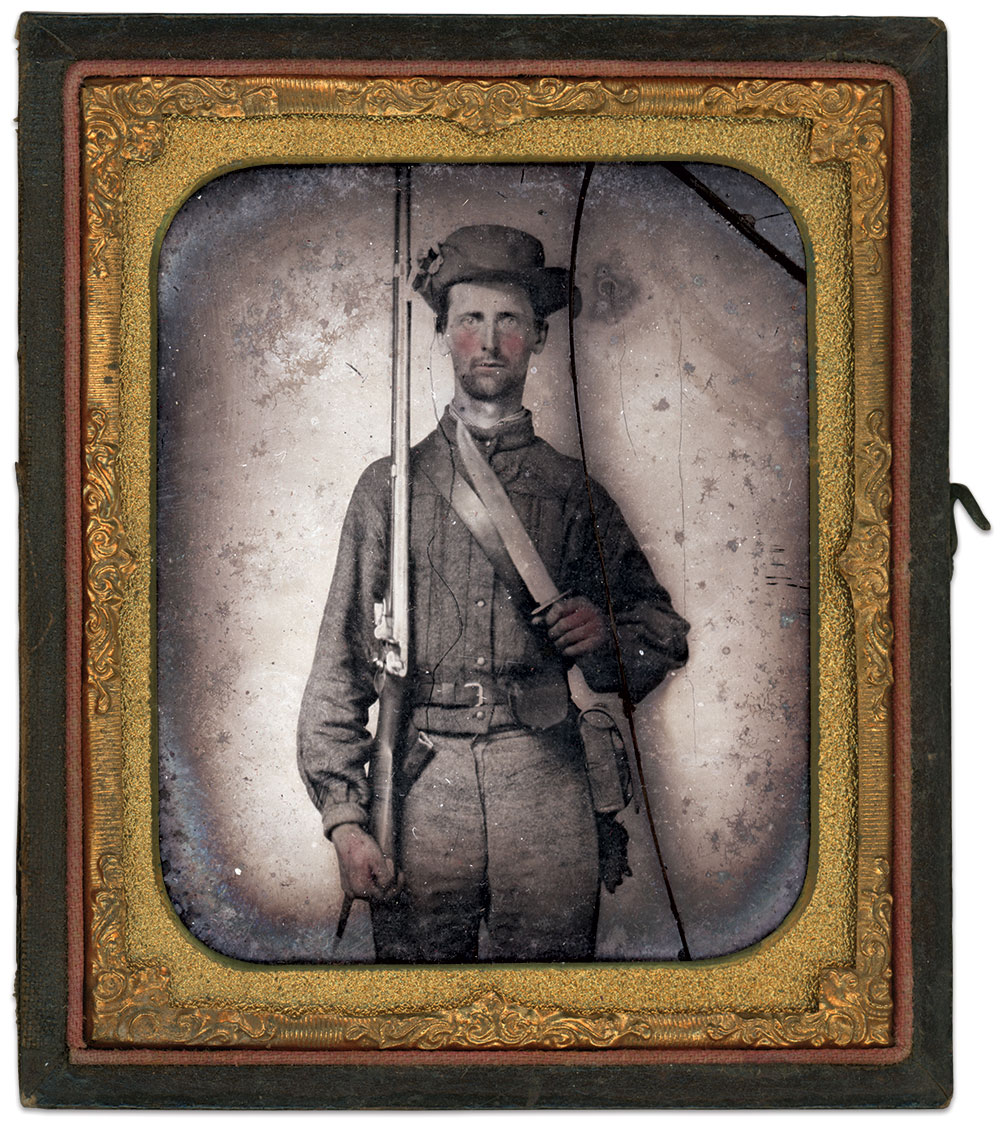

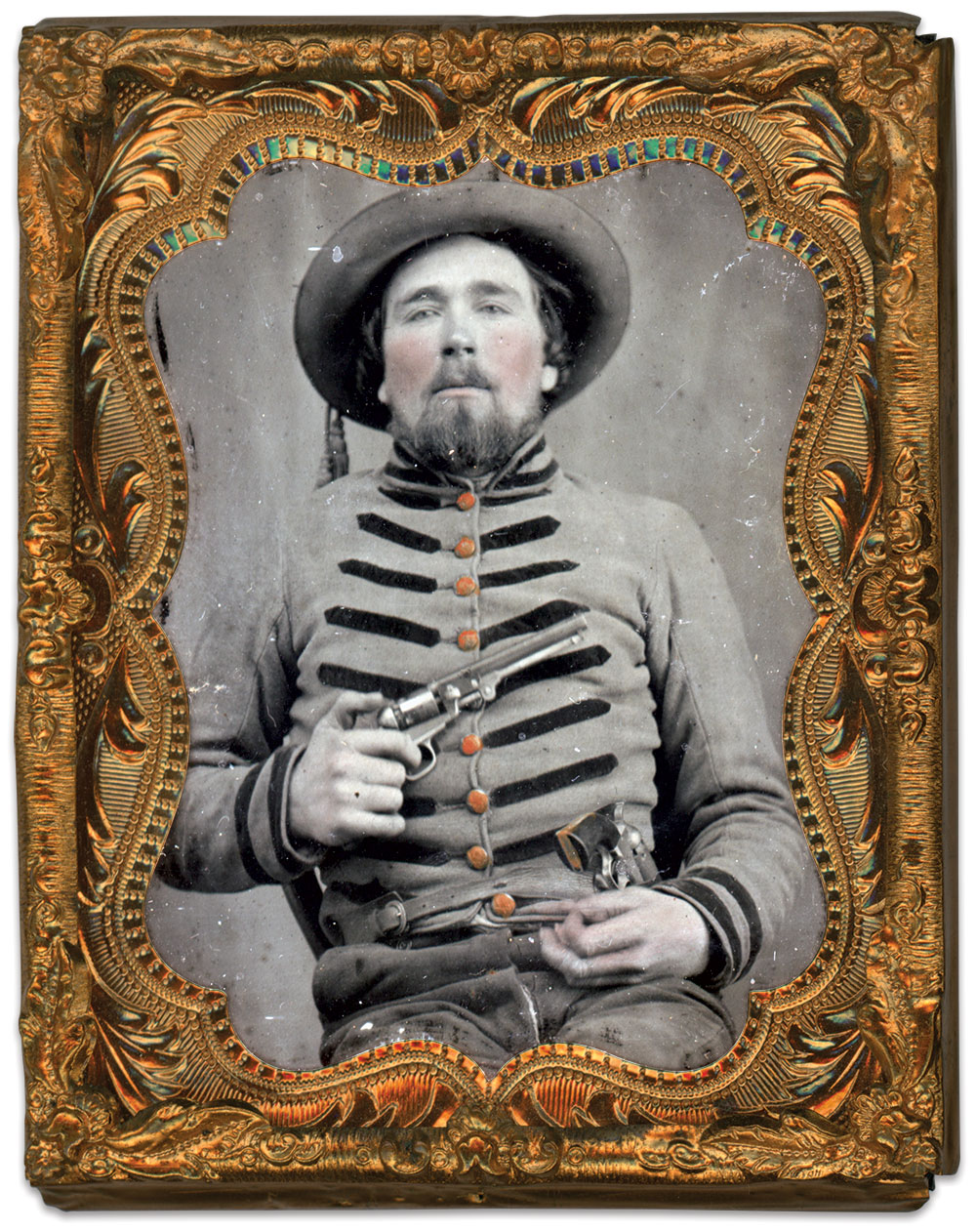

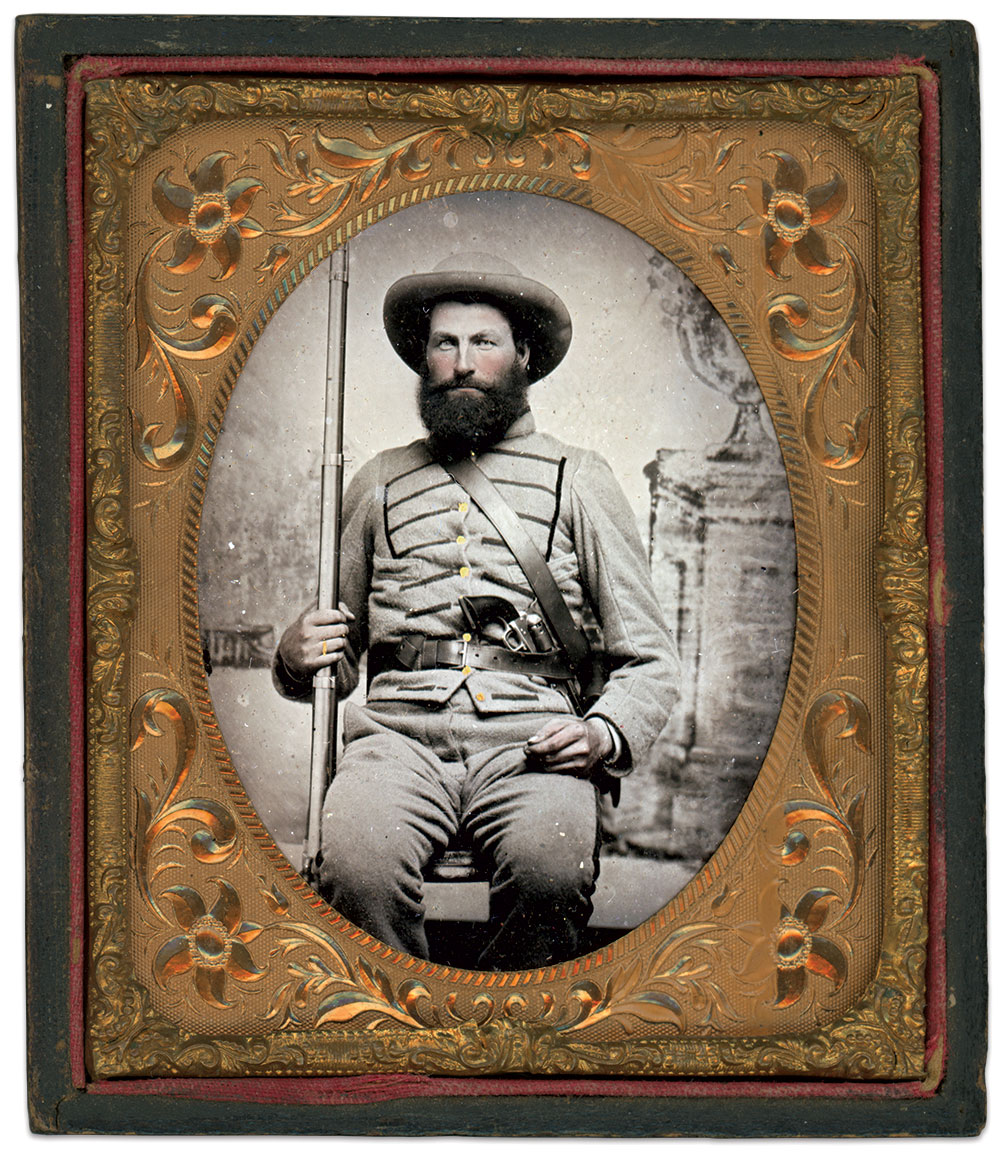

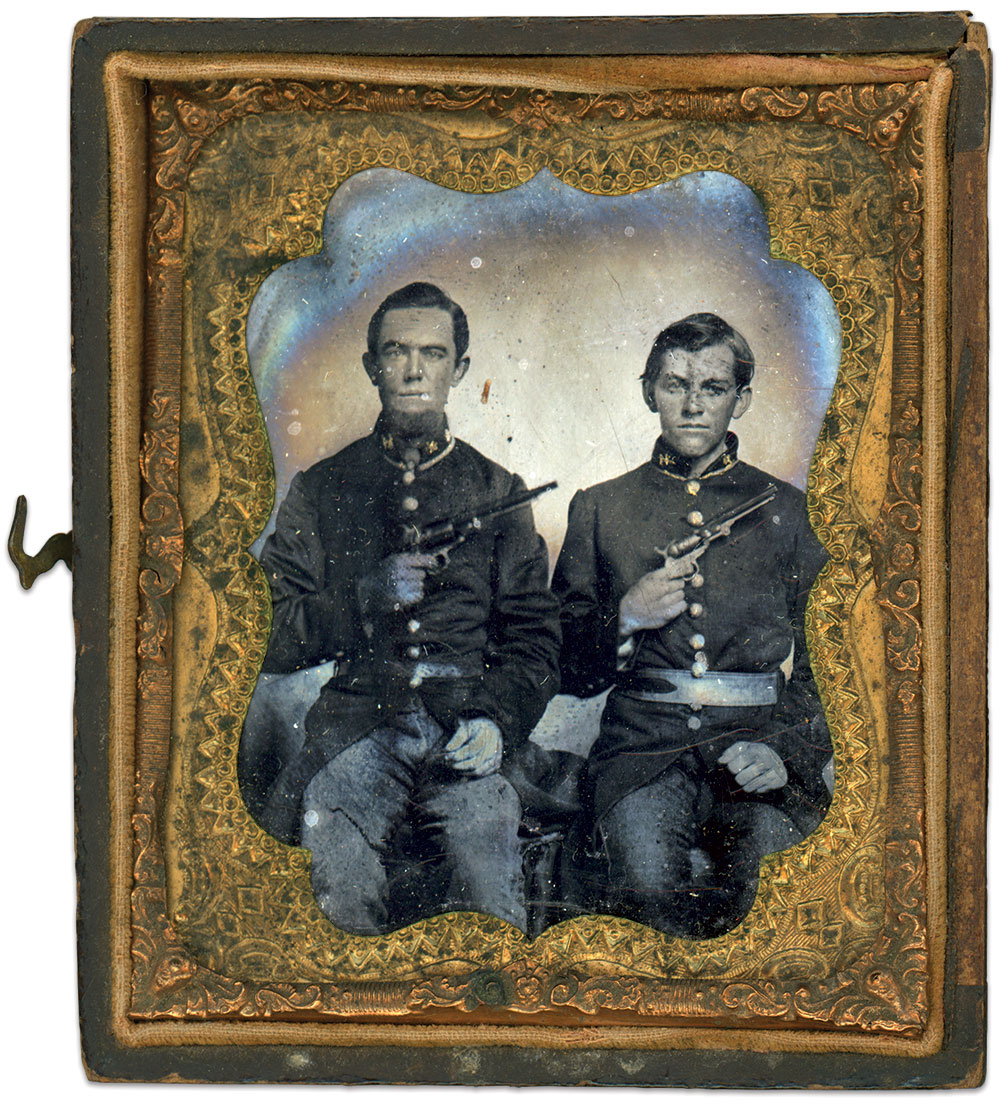

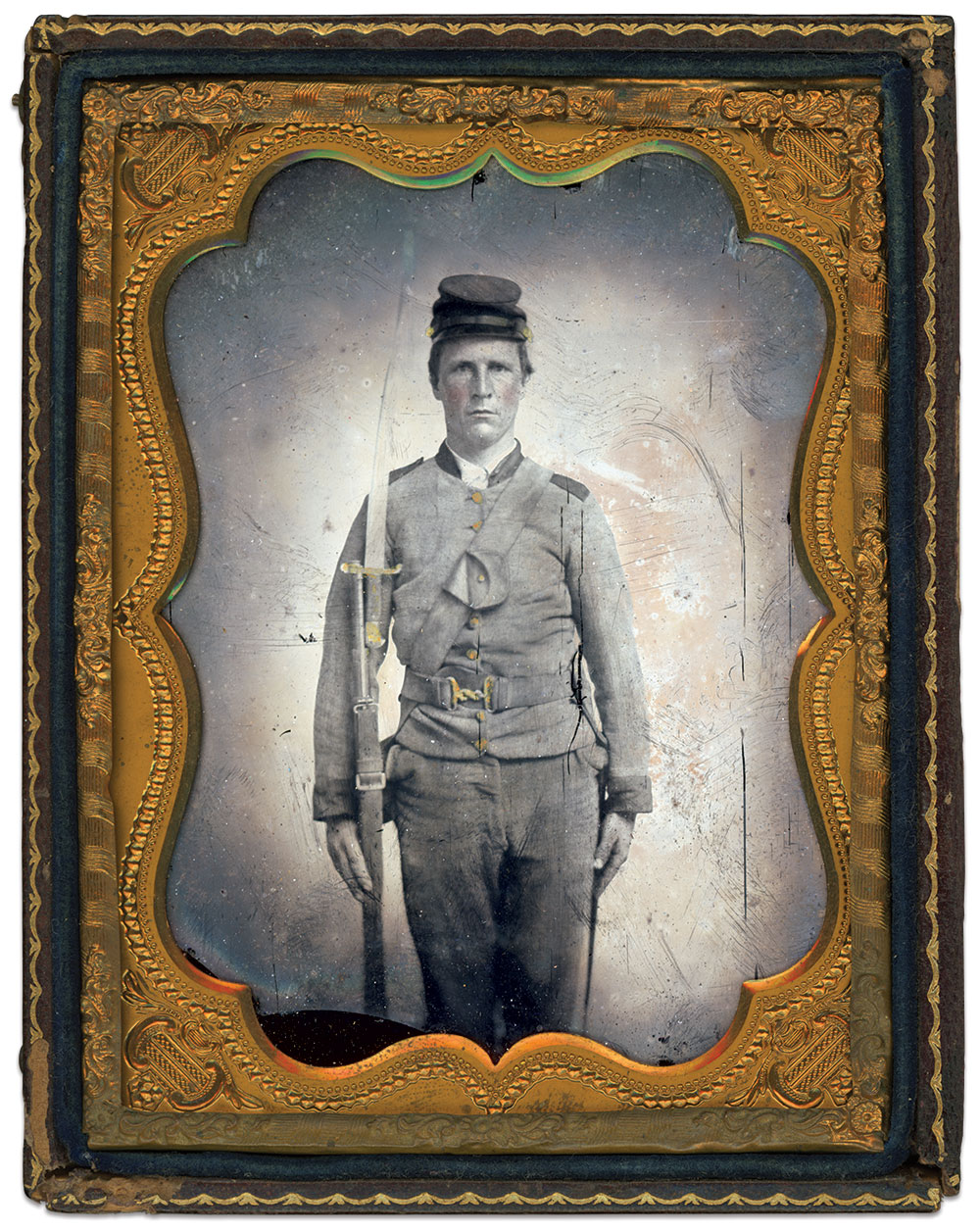

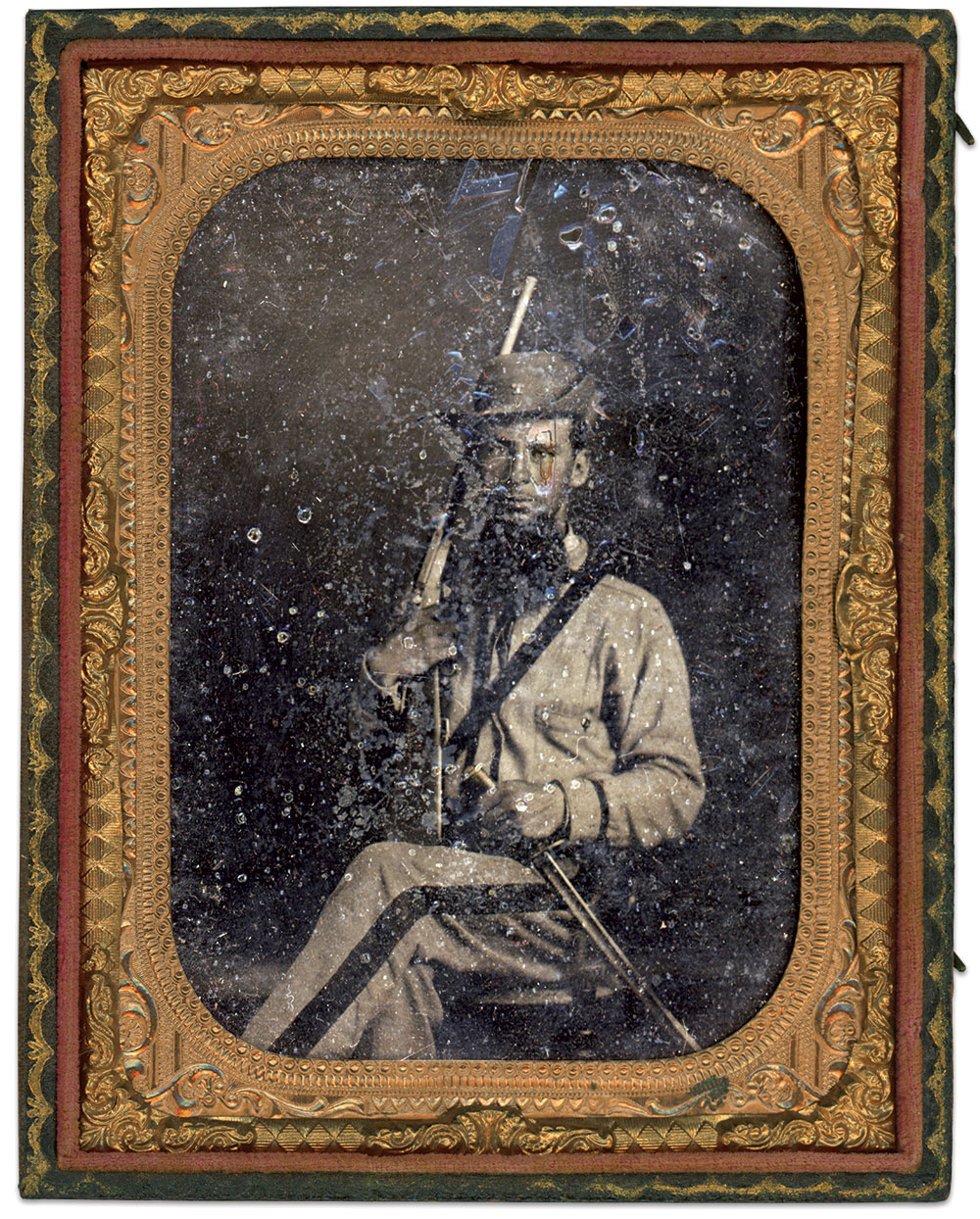

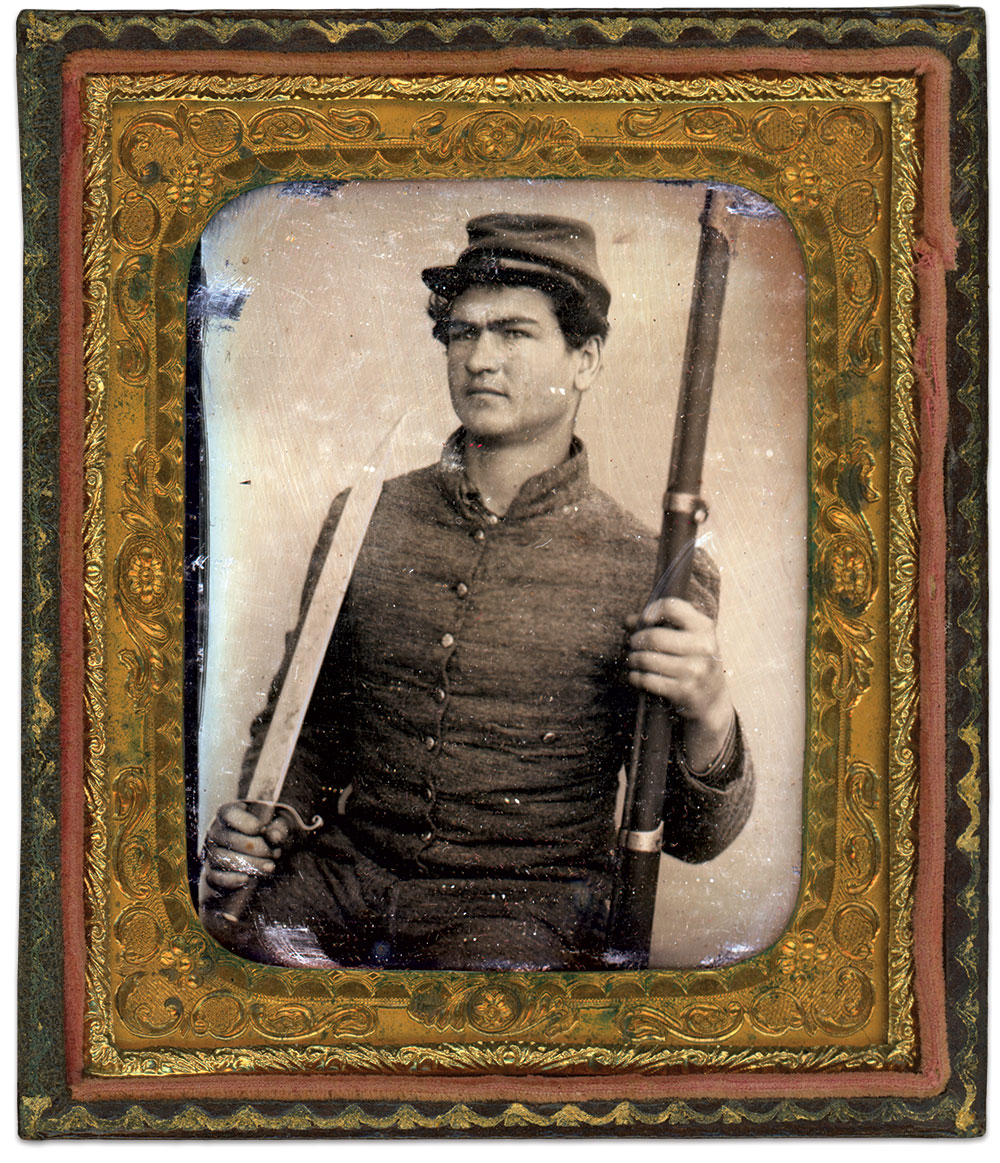

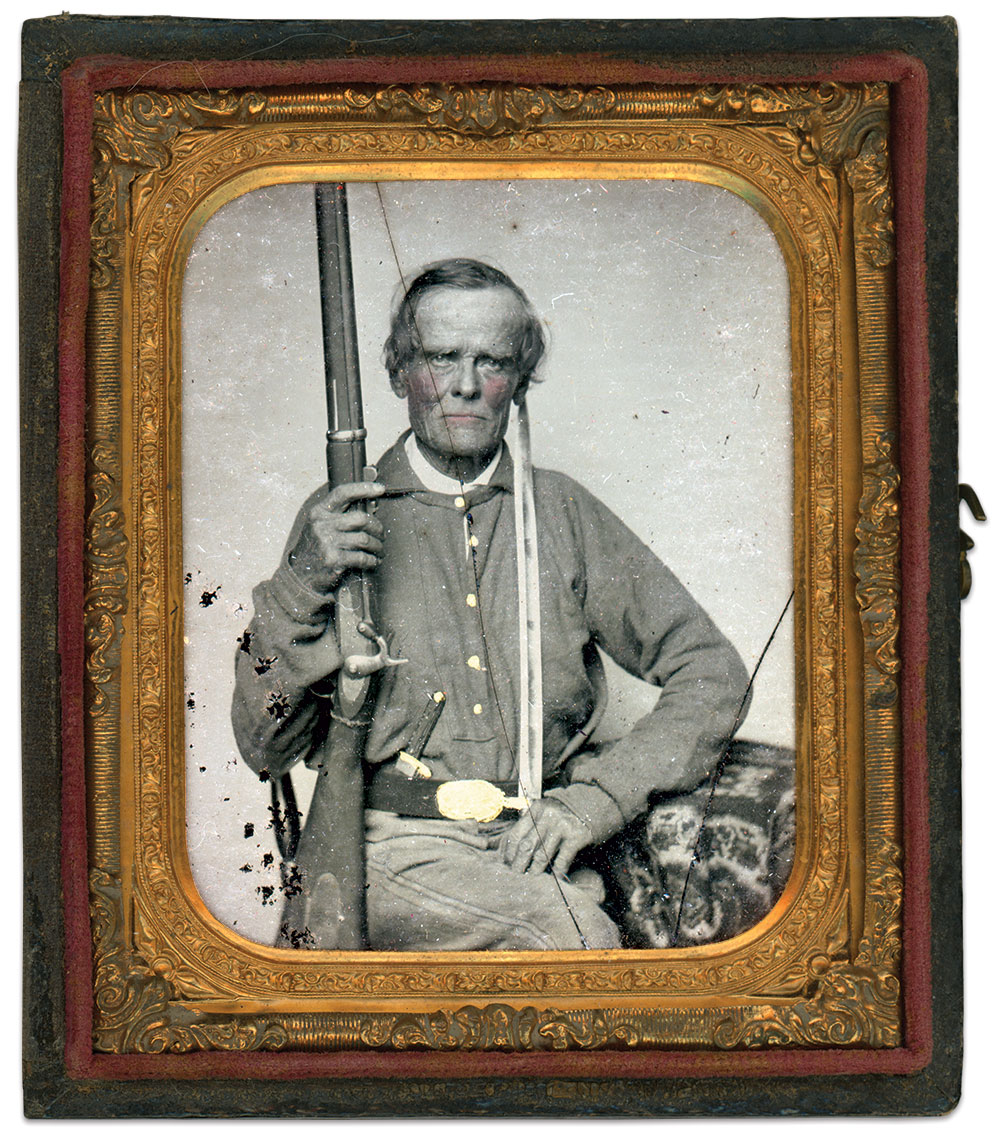

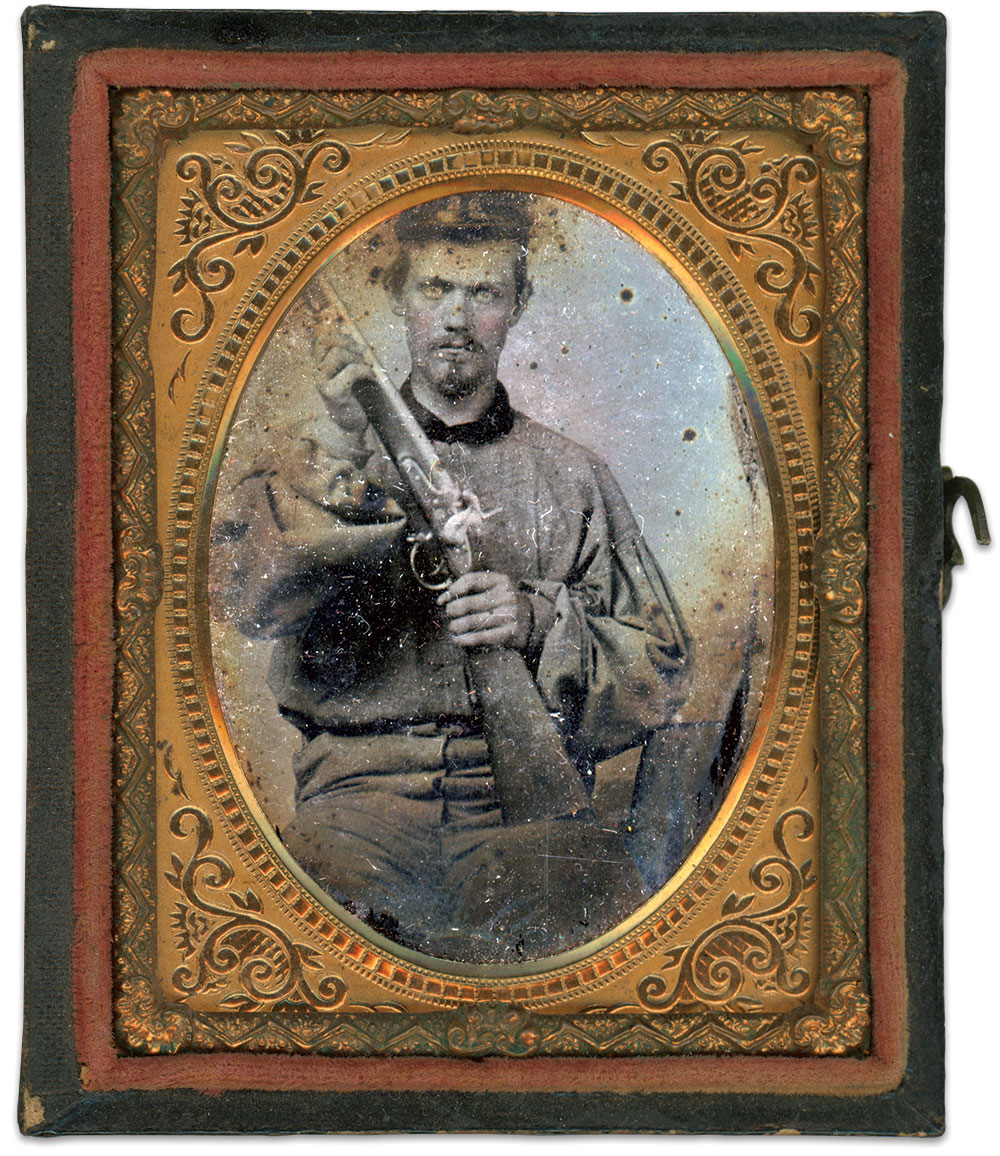

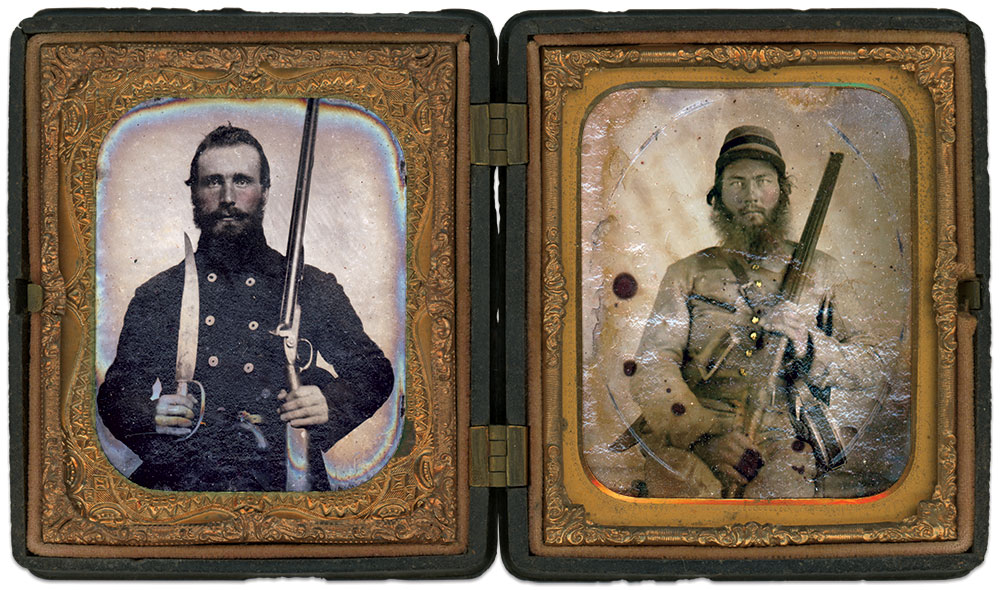

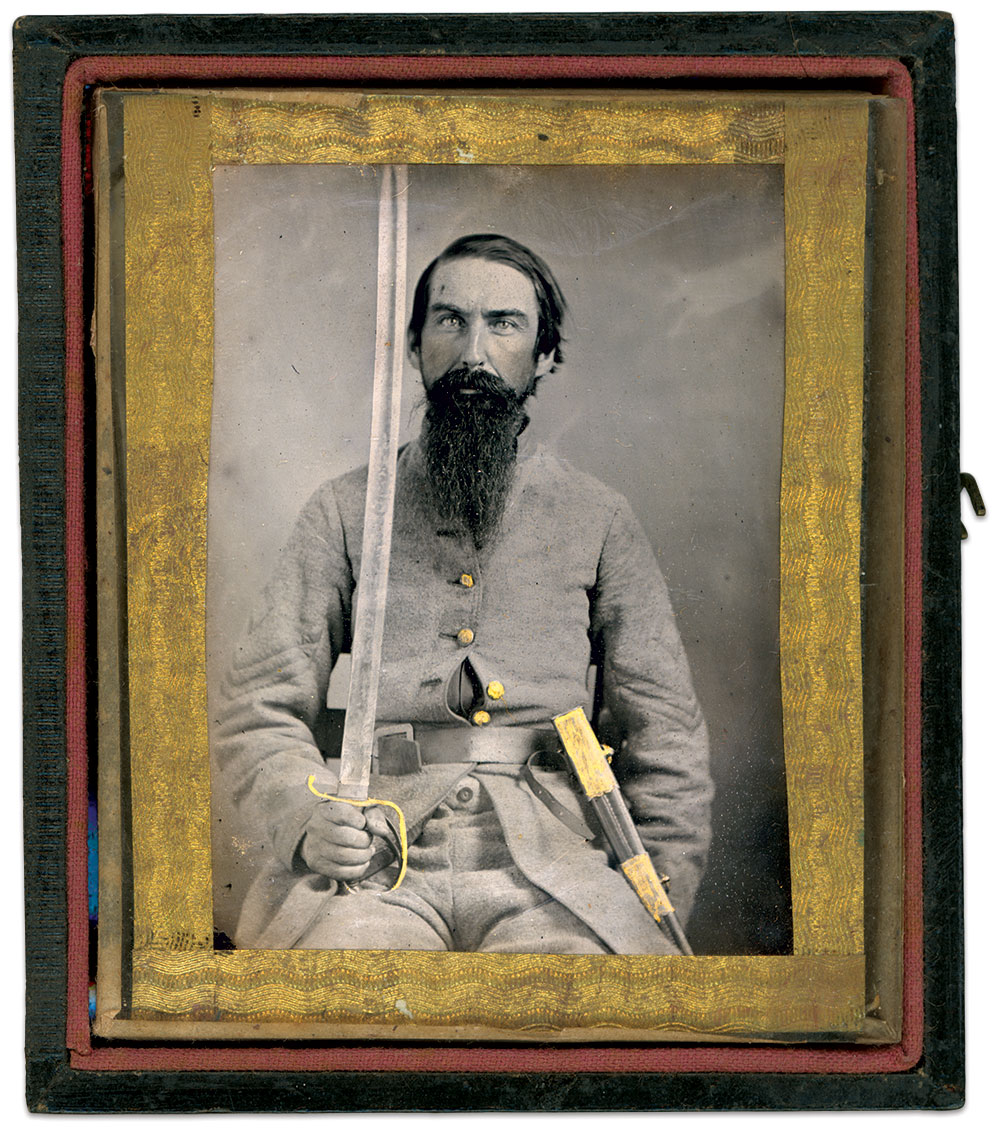

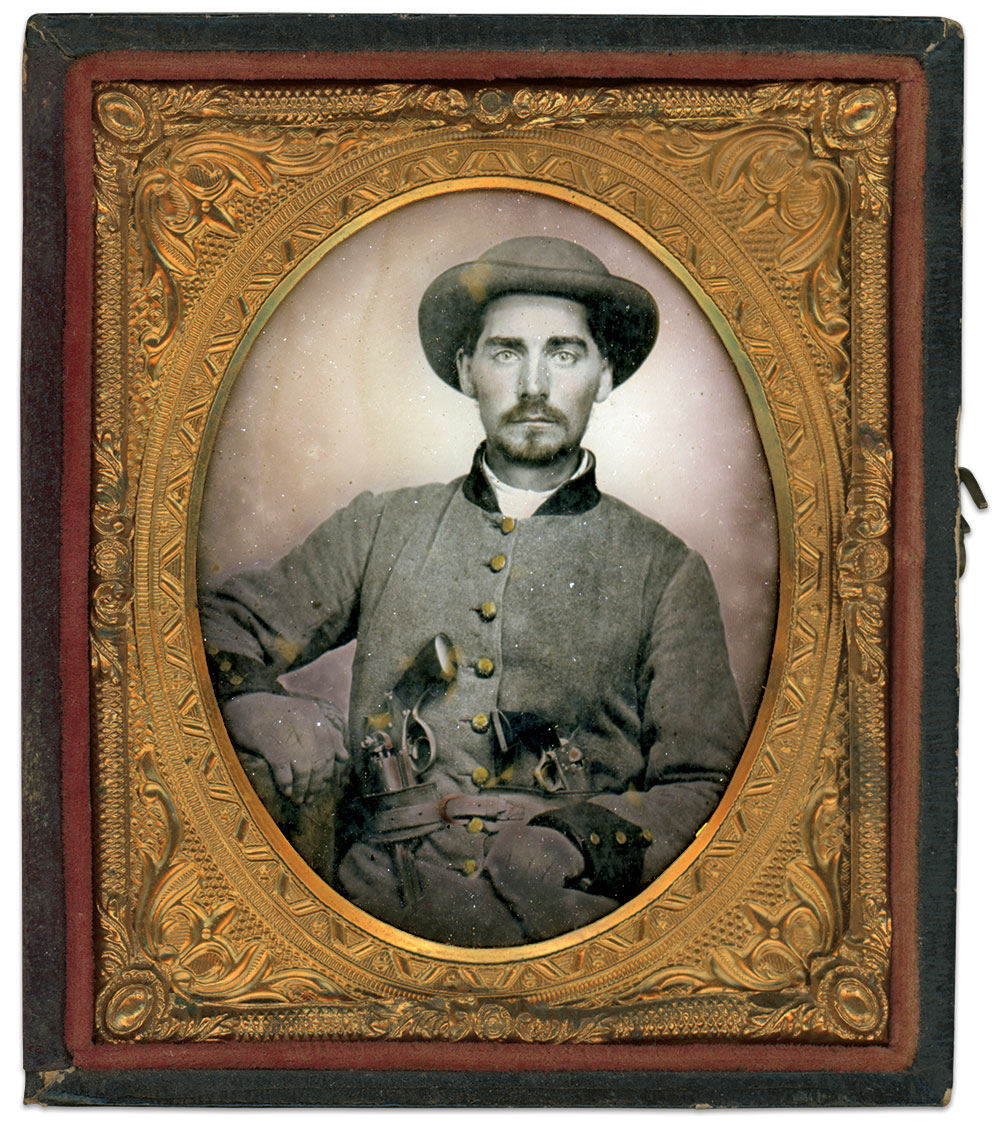

Images were stacked in groups everywhere in the study: A treasure of daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes of Confederate and Union Civil War soldiers, citizens and antebellum military men. Portraits of sons of the South dominated the collection.

Herb’s passion for images equaled his fascination with weapons. Photographs of fully armed soldiers posed with muskets, revolvers, and Bowie knives really delighted him. Considering Herb’s orientation, the images might be better described as guns posed with soldiers.

Herb started collecting photographs as a teen in the 1950s, as the approaching Civil War centennial received national attention. One of his early purchases, a signed carte de visite of Abraham Lincoln, cost him 10 cents.

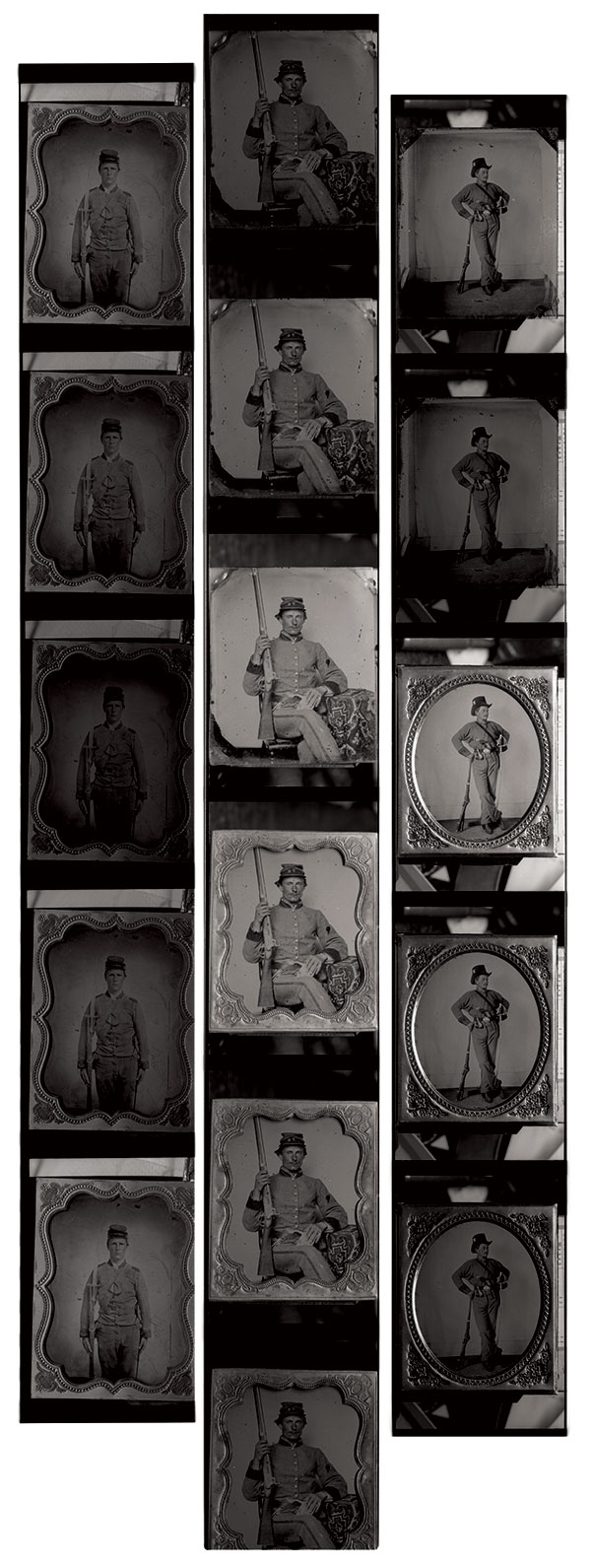

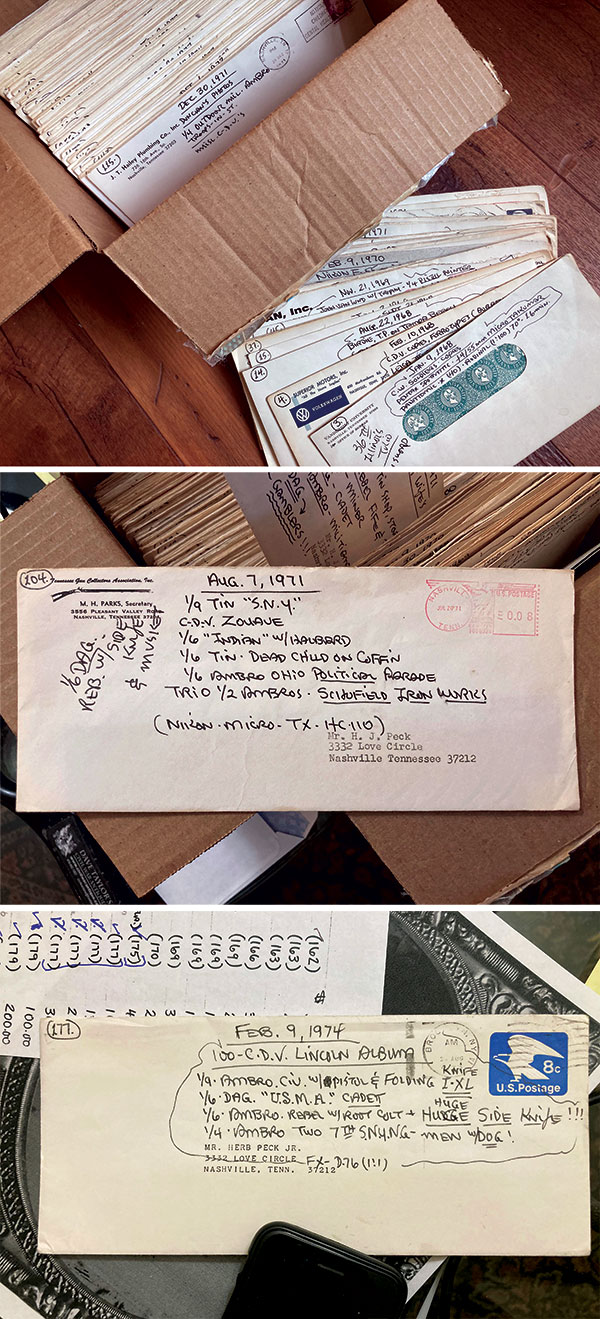

Over the years, Herb amassed a premier collection. About once a month, he photographed his latest acquisitions with black and white film. Then he developed the negatives and inserted them into used business envelopes. Herb wrote the date and descriptive information on each envelope, and filed them with hundreds of other envelopes. The negatives were not all images from the collection—they were mixed in with portraits of celebrities he took on the Vanderbilt campus, family and friends.

This was Herb’s archiving system.

Herb made prints from some of the negatives of the images in several sizes, and stamped them with his name and address on the back. He sent some to editors for publication in various media. Images from his collection were published in The Civil War by Ken Burns and in more than 50 books, magazines and articles, including Time Life’s The Civil War series, the Confederate Faces series, Civil War Times and Military Images. One of his images graces the cover of an edition of Stephen Crane’s classic, Red Badge of Courage. Herb also sent prints to collectors.

Herb reigned as a pre-eminent collector of Confederate images in the 1960s and 1970s. The content and quality of his collection stood out among his peers. His technical abilities as a photographer enabled him to easily distribute his images and promote his name. His charismatic personality kept everyone smiling.

Herb became the face of image collecting.

“If there was a Mount Rushmore for image collectors, Herb Peck would be on it,” noted Buck Zaidel, a Military Images Senior Editor. “He was an important collector, among the earliest to recognize the significance of these images.”

The altercation

In Herb’s study during the afternoon of September 29, police dusted the crime scene and found no fingerprints, a strong indicator that the perpetrator or perpetrators wore gloves. The neighbors saw nothing. No witnesses came forward.

If the guilty party could be found, the “victim will prosecute,” noted the police report.

Herb believed he knew the man who killed his soul. The Sunday before the burglary, he had invited a longtime acquaintance into the inner sanctum, a fellow gun enthusiast suspected of shady dealings in the past.

Herb’s emotions remained raw and unhealed following the burglary. Four weekends later, on October 21-22, he went to the Nashville Flea Market. Held in a group of buildings the third weekend of every month, it was a favorite place to hunt for guns and images.

Bruce Jackson joined Herb. The two had become acquainted about three years earlier, after Bruce relocated to Nashville from Knoxville. Courteous, mild-mannered, even-tempered and a keen observer, Bruce shared Herb’s passion for guns.

Bruce and Herb were inseparable. They talked by phone every weekday morning. Felicity described them as clones, noting they shared the “same political views and views on life in general.”

The man abruptly ended the confrontation with four words that haunt Bruce and Felicity to this day. ‘Can you prove it?’

Bruce also enjoyed his motorcycle, going on spur-of-the-moment long-distance adventures with fellow bikers. Memorable journeys included Sturgis, the wild annual rally in South Dakota. Bruce sold his motorcycle and stopped riding in 2018.

But his passion for guns still burns bright.

Bruce remembers the October 1978 flea market because of a tense altercation. He and Herb combed the tables as usual and made their way out. As they approached the exit, the man Herb believed responsible for the crime walked in through the same door. Herb’s body stiffened. His face burned crimson. His blood was up. Bruce thought Herb was going to draw his weapon—Herb carried his Smith & Wesson Model 36 revolver, and Bruce a Model 1911 Colt pistol. If the man carried a firearm—he was known to—Bruce did not see it.

Bruce stepped aside to make space for Herb.

“Man, you stole my stuff,” Bruce remembers Herb saying.

The man vehemently denied it. Herb pressed him. Temperatures rose to the boiling point.

The man abruptly ended the confrontation with four words that haunt Bruce and Felicity to this day. “Can you prove it?”

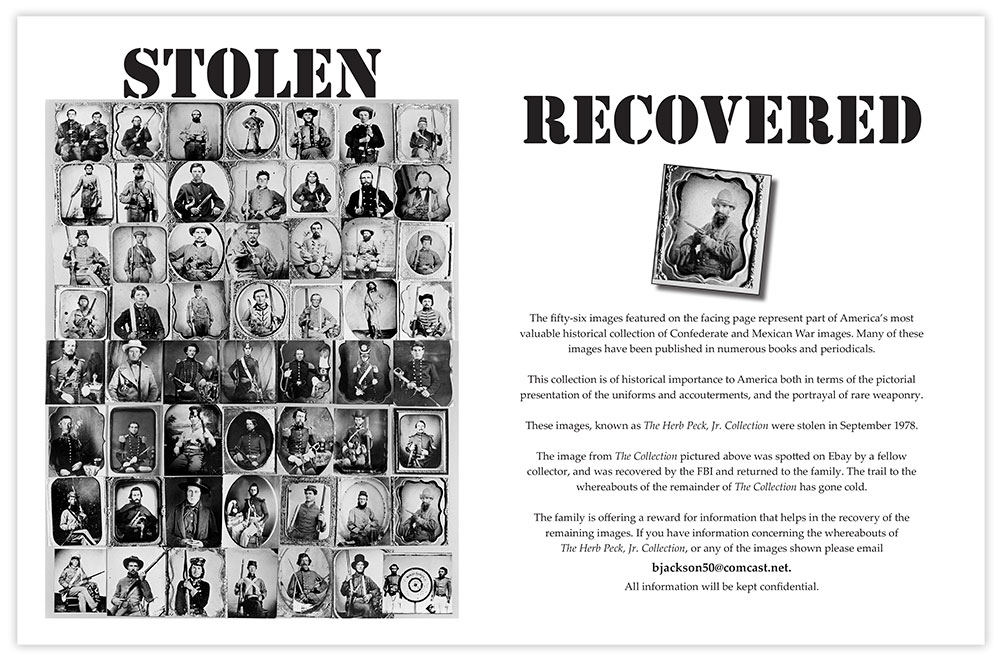

The poster

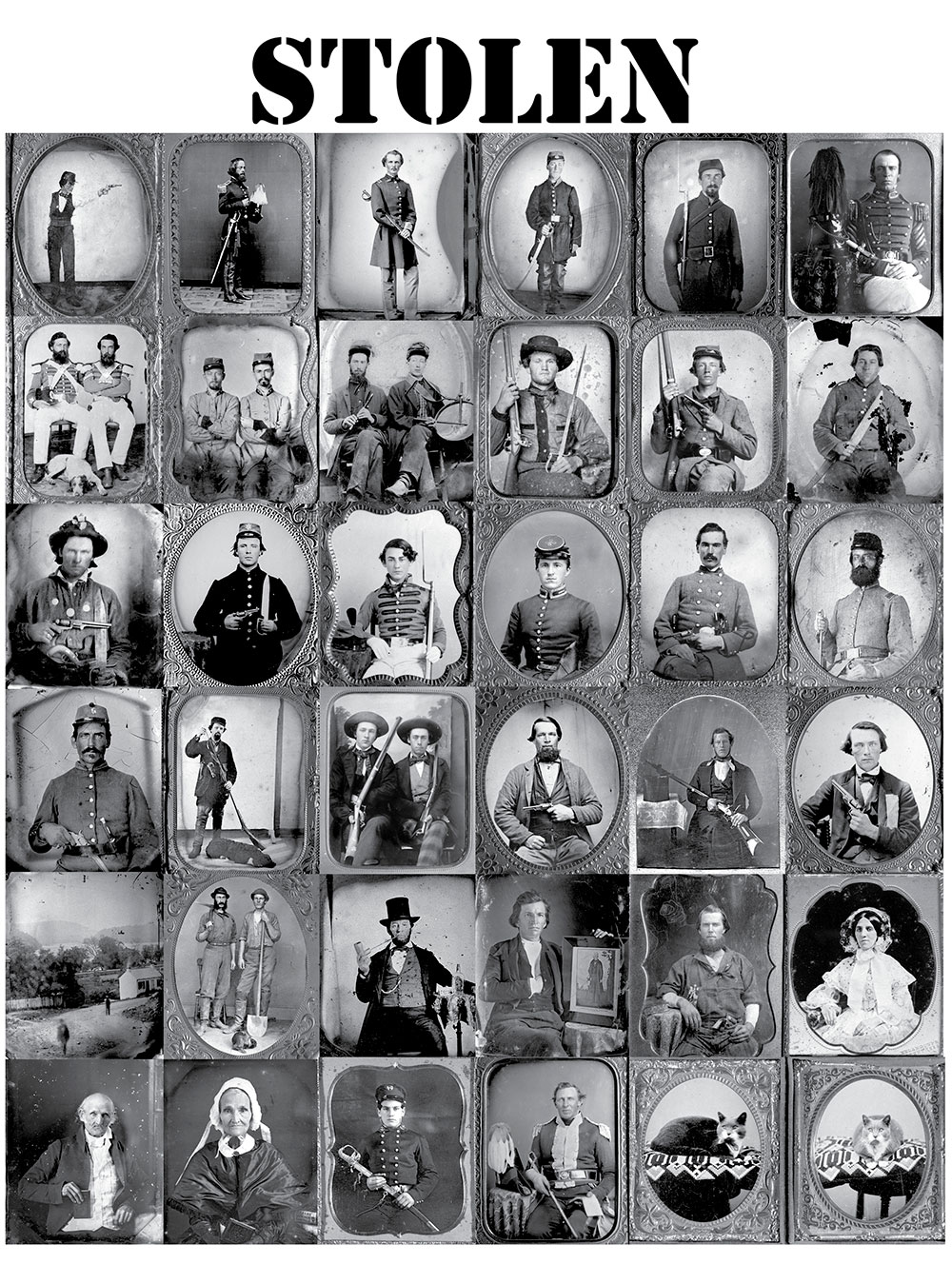

After the encounter, Herb turned to his archive of negatives and prints to spread the word. Before the end of October 1978, he had a poster printed on letter-size paper. It featured 56 of his images, arranged in eight rows and seven columns, with the headline “Stolen” and contact information. Herb and Bruce distributed this poster to all the shows they attended, hoping that someone might have purchased or traded for one or more of the missing images.

The thumbnail-sized photos on that black and white poster circulated across the country and took on lives of their own. Each became stamped into the brains of image collectors. Sadly, other collectors would suffer the same fate as Herb in years to come. The small size of early images made them easy to swipe off a distracted dealer’s table during a crowded show with a sleight of hand. Ironically, the small size was a feature to the families and loved ones who received them during the war, and, much later, the collectors who prized them.

No theft received the attention and rose in the awareness of the image collecting community as the Love Circle burglary.

Meanwhile the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department located two of the guns. Each showed signs of serious distress, an indication they had probably been used to commit crimes. None of the images surfaced.

Bruce reached out to law enforcement, including the Memphis office of the FBI, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI), the district attorney for Davidson county (Nashville) and local police to no avail.

The lack of progress frustrated Felicity and Bruce, but was perhaps not surprising considering the lack of clues and witnesses.

The odds that law enforcement could apprehend the perpetrator of a home burglary are historically slim. Over the past few decades, only 10 to 20 percent of these crimes are solved or otherwise cleared. A recent study found that only 13 percent are successfully resolved.

Years passed. The Love Circle case stagnated and went cold.

On Feb. 4, 2004, Herb planned to spend the day at the Heart of Country Antique Show, held annually at the Opryland Hotel. He didn’t make it. Felicity found him when she returned home from her work, about 5:30 p.m. Herb was brushing his teeth when he fell victim to a heart attack three days shy of his 68th birthday.

He did not live to see any of the stolen images recovered.

A break in the case

After Herb passed, Bruce recalls, an alert collector spotted one of the images pictured on the poster for auction on eBay. Bruce alerted the FBI. The Bureau dispatched a special agent with expertise in art from its Indianapolis office to recover the image on June 7, 2006—almost three decades after the burglary.

Then, the trail turned cold again.

In late 2016, Tim contacted Military Images to reboot the search. Now a professional actor in California, he had previously worked as a graphic designer. Tim dusted off his art skills and created a two-page advertisement. On the left-facing page, a version of the original 56-image poster. On the right, a picture of the recovered image accompanied by an appeal to the community to assist in finding the remaining images. It appeared in the Winter 2017 issue.

The collecting community responded. More of Herb’s images surfaced on eBay and collectors promptly contacted Bruce, who passed the information to law enforcement. The case received a boost when two young special agents in the Nashville office of the FBI became aware of the cold case and the amount of money involved.

The leads revealed that the locations of the images coalesced geographically around the southern middle counties of Tennessee. Uncounted hours of investigation and many interviews later, the Nashville agents contacted local law enforcement in Ethridge, Tenn. On Oct. 29, 2020, Ethridge police officers and FBI agents seized 39 of Herb’s images in a raid.

Law enforcement declined to disclose if any arrests were made.

The number of images returned stands at 40—the 2006 recovery plus the 2020 seizure.

Herb’s master list, and a twist

One might assume that the original poster is a complete visual representation of all the stolen images. It is not. There were more images taken from Herb’s study—a total of 114 ambrotypes, daguerreotypes and tintypes, plus an unspecified number of cartes de visite.

We know that 114 images existed thanks to Herb, who compiled a list. He did not submit this list with the original police report filing that included an inventory of the guns and cameras.

The likely explanation for the omission of the list of photographs from the police report is time. The theft occurred between 9 a.m. and noon on Sept. 29, 1978. Exactly when Herb discovered the break-in is not known. But he called the police at 1:30 p.m.. They arrived at Love Circle at 1:50 and filed the report at 2:15. If there was a chance to capture the criminal or criminals and return the items, everyone needed to move quickly. There was simply not enough time to create a detailed list of the photographs.

One might assume that the original poster is a complete visual representation of all the stolen images. It is not. There were more images taken from Herb’s study—a total of 114 ambrotypes, daguerreotypes and tintypes, plus an unspecified number of cartes de visite.

At some point after the police left, Herb set about this task. He turned to his archive of negatives. This resource enabled him to produce a five-page, hand-written inventory of missing images. Herb cataloged each item based on information previously recorded on the envelope containing the negative: plate-size, format, a brief description of the contents, the number of the negative envelope, and the estimated value. When Herb finished, he had identified 114 stolen images. He created an entry numbered 115, and it noted the miscellaneous cartes without reference to any negatives.

Herb valued the collection at $28,565 in 1978 dollars. Adjusted for inflation, the total soars to $130K. The current market value is considerably higher. According to one estimate, it is in the neighborhood of $500K to $700K.

Why Herb featured only a portion of the images on the poster is an open question. One possible answer is that he worked quickly with the prints he had on hand to create a one-page document that could be inexpensively printed and distributed.

Had Herb lived into the current digital age, he might have made a comprehensive, all-encompassing poster featuring every stolen image. He and Bruce would have distributed hard copies at shows and as digital files by email, text and direct messages, and on social media. Such an effort may have attracted more news coverage and interest from law enforcement.

We now know that 56 of the 114 stolen images were reproduced on the original poster. By simple subtraction, 58 were not included.

Thanks to Herb’s list and archive, a new poster of previously unknown stolen images can be created.

Creating a new poster

In early December 2022 at the Middle Tennessee Civil War Show, popularly known as The Franklin Show, Bruce found me at the Military Images table on the top tier of the Williamson County Agriculture Exposition Center. It was good to see him for the first time since the pandemic. We exchanged pleasantries and talked a bit about the case. In past conversations, Bruce told me that Military Images would have an opportunity to tell the story someday.

Someday had arrived. Felicity and Bruce were prepared to share.

On Jan. 26, 2023, we met at Felicity’s home in Nashville. I went into the interview with a preconceived notion that this story would document the end of the case. Closing the books on a sad chapter in collecting history. Full stop.

Then I learned of the existence of Herb’s archive of negatives, the list of 114 stolen images, and the original poster being only a partial representation. I realized that the story would be forward-looking, not backwards. This was the beginning of a new chapter in the 45-year-old saga.

I left Nashville with a commitment to Felicity and Bruce to return and digitize the negatives. Six months later, on July 15-16, I arrived at Felicity’s home for a full weekend of scanning, photographing and interviewing.

Bruce prepared by pulling envelopes from the archives that matched the numbers on Herb’s list of images. Bruce discovered to his consternation that some of the envelopes had gone missing. How they disappeared is not known. They may have been misfiled or mislaid by Herb during the 26 years between the burglary and his passing. About a year earlier, a friend received permission to scan some of the negatives. Some could not now be found. It is likely that they are somewhere in the vast archive of Herb’s lifetime of work as a photographer.

In the end we found 35 negatives (36 images) of the 58 images listed that did not make it on to the original poster and were not part of the group of 40 recoveries (27 images on the original poster and 13 not included.) The new poster features the 36 images.

Bruce, Felicity, and Tim, now ask for help to find them.

The efforts of the collecting community have been key to success. “I believe our collectors were most important in keeping the story alive,” notes Bruce. Felicity has similar feelings, “I remember how distressed the collectors were at the time of the burglary.” She adds, “It has always been a comfort to me that others care about the importance of these images as historical, visible and tangible evidence of this country.”

They will not rest until all the images are found.

In the meantime, Bruce plans to sell the recovered images on behalf of the family. Herb would have wanted his collection to be returned to the community he loved.

Original poster

56 images displayed, 27 recovered (highlighted in green), 29 missing

New poster

36 images not included on the original poster, none recovered

Contact Bruce Jackson: bjackson50@comcast.net

All information will be kept confidential

Recovered Images

27 on original poster, 13 not on original poster

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Searching for Herb Peck’s Images: 45 years after the theft of his pre-eminent collection, an update—and a new call to action”

Comments are closed.