By Brendan C. Hamilton

A column of soldiers marched along a Southern road, their well-worn brogans tramping over hard dirt and sloshing through mud. Bronzed faces passed, one-by-one, undeniably weary, but tinged, perhaps, with a shade of hope. It was the spring of 1862, and as one soldier of the 29th Indiana Infantry explained, for weeks he and his comrades had been “performing wearisome marches, living on hard crackers and fat pork, sleeping on the damp ground without tents, [and] suffering every conceivable deprivation…”

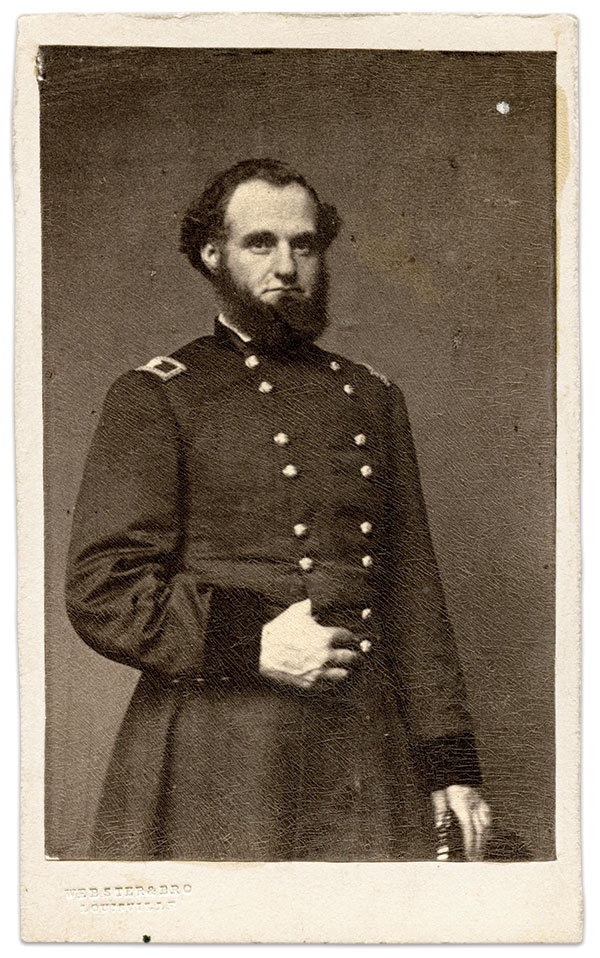

Part of Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio, the 29th Indiana fought hard to repel the Confederate Army of the Mississippi on the Battle of Shiloh’s tumultuous second day, and was now pressing forward toward the critical railroad junction at Corinth, Miss. Union Brig. Gen. Richard Woodhouse Johnson, who commanded a brigade in Alexander McCook’s division of the 20th Corps, had missed the fight while recuperating from illness. He arrived a week after its conclusion. As he witnessed the fatigued survivors, he may have marveled, as Walt Whitman did, to behold “the brown-faced men, each group, each person a picture.”

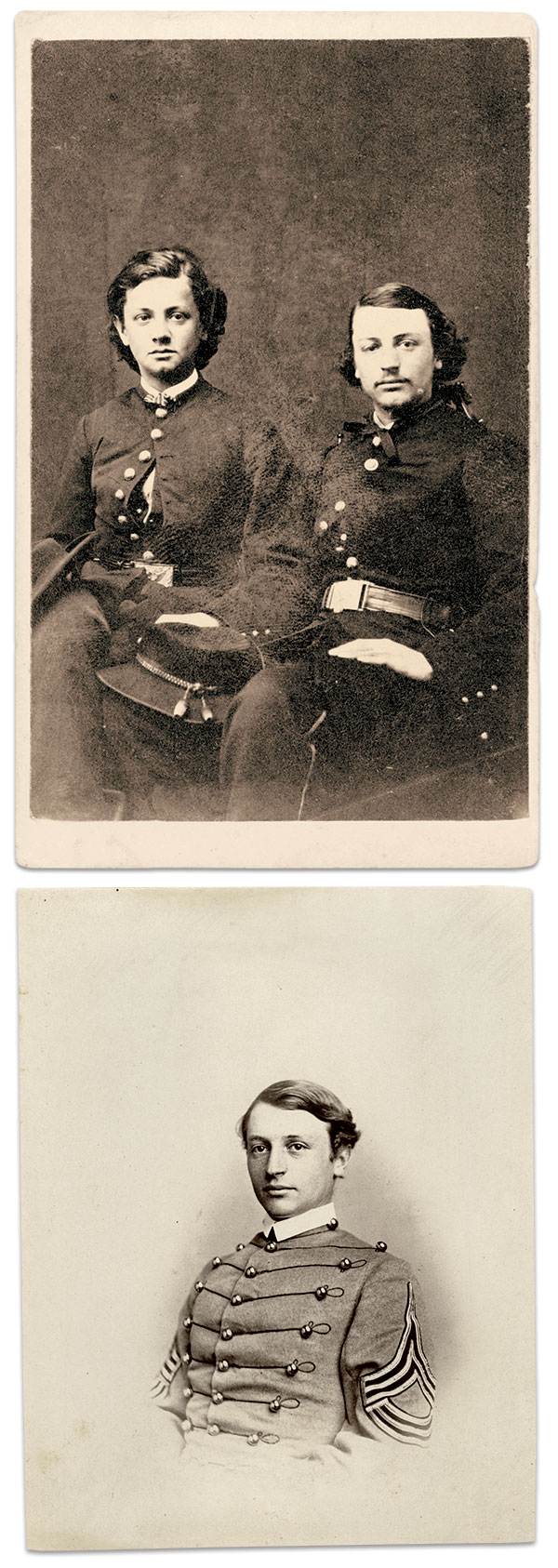

One picture in particular caught Johnson’s eye—the youthful visage of Pvt. Frank N. Sheets of the 29th. “His handsome, girl-like face attracted my attention,” the general recalled. “I directed him to report to me on his arrival at camp.” When Sheets reported to Johnson, the general was so impressed with the private that he immediately asked him to join his staff as an aide de camp.

Frank Sheets was born and raised in Madison, Ind., a flourishing city nestled in rolling hills along the banks of the Ohio River. His father, Francis, died when he was a toddler and his mother, Clara, subsequently left Indiana for Washington Territory, where her brother served as the territory’s first Surveyor General. Young Frank was left behind in Madison in the care of another uncle, a bank teller named Mark Tilton. Sheets attended school nearby at Madison Seminary and, by his teens, found employment as a clerk in an express office, sending the bulk of his wages to his mother out West.

Sheets was just a child as the Secession Crisis boiled up around him, and it likely created tensions–if not rifts–within his own family. His mother’s side, the Tiltons, had roots in Maryland and Delaware and included slaveholders, some of whom would eventually fight for the Confederacy. The same could not be said for the Sheets side of the family. In fact, Sheets’ grandfather, Maj. John Sheets, was a rough-and-tumble frontiersman who risked his life rescuing Griffith Booth, a former enslaved man, from a pro-slavery mob that attempted to drown Booth over his involvement in the Underground Railroad.

One can only speculate whether the legacy of his grandfather’s courage was on his mind when Sheets made his decision to enlist in the Union Army. The boy was only 15 or 16, and, like other underage volunteers, may have had to make several attempts at enlisting before he was accepted. The regiment he fixed upon was the 29th Indiana Volunteer Infantry, a unit recruited and organized in Northern Indiana—the opposite side of the state—in the summer of 1861. That Sheets’ uncle, Mark Tilton, was married to the sister of the 29th’s lieutenant colonel, David M. Dunn, almost certainly played a factor in this decision.

The young recruit crossed the mighty Ohio and met up with the 29th at Camp Nevin in Hardin County, Ky., in October 1861. At the time of his enlistment, Sheets was recorded as 5 foot 4 ¼ inches tall, with dark eyes, dark hair, and a light complexion. Perhaps due to his family connection or his experience in the express office—or even a combination of the two—Sheets was detailed the following month as a messenger to the colonel. He also served as regimental postmaster, though his service records do not provide a date for this role.

The fall and winter of 1861 was a harsh time for the green soldiers crowded together at Camp Nevin. Disease spread like wildfire through the various regimental encampments. Sheets was among those who took ill, and the attending doctor feared it was typhoid. Dunn secured Sheets a furlough in December to return to Madison to recover. While there, the young soldier wrote to his mother in Washington, sharing news from the family and urging her to write more often. He painted a bright picture of his time in the military thus far. “I like a soldiers life very much,” Sheets said, “and I think I will like it Better when we get down where we will have some fighting to do.” Above all, he dreamed his mother would come back to Indiana. “The longer I stay [in the Army], the more I like it, but I will leave it as soon as you are at home and say the word.”

Sheets recovered from his illness and returned to the 29th sometime after Christmas, serving with it in camps along the Green River and on the long marches through Kentucky and Tennessee. He fought beside his comrades during the second day of the bloody Battle of Shiloh, where the regiment suffered 80 casualties helping to repel and counterattack the Confederate Army of the Mississippi. For Sheets and the other boys of the 29th, Shiloh would be their first experience of the full horrors of Civil War combat; the sensations of battle, and the sights and sounds of its aftermath, would haunt its survivors for years to come.

It was perhaps these very horrors that Gen. Johnson hoped to shield Sheets from when he appointed him aide de camp in May 1862—just a month after Shiloh. In December, Johnson promoted Sheets to a first lieutenant and transferred him to Company D of the 4th Kentucky Cavalry. Why Johnson transferred Sheets is unclear. It may have been a simple move to fill an open officer’s position or a personal preference of Johnson, a native Kentuckian.

Though there are gaps in Sheets’ record between the time of his appointment and promotion, it is probable that he was with Johnson during the unsuccessful pursuit of Confederate Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry that summer. He was certainly serving as Johnson’s aide after the general was placed in command of McCook’s second division, which by late 1862 had become part of the Army of the Cumberland.

Sheets participated in and survived the Battle of Stones River. On Jan. 14, 1863, having not heard from her son for over a month, Clara wrote expressing her hope that he emerged unscathed. “Oh my dear son,” she said, “you know not the anxiety I feel & will for three weeks on your account. I pray my heavenly Father that you are spared to me & that you have not been killed or maimed…I have had many sorrows, I trust I may be spared this one.”

Clara acknowledged that Sheets had mentioned in a previous letter that he was dissatisfied with his position with Johnson. “I know not the nature of your unhappiness—therefore cannot give advice,” she remarked, “[but] you must remember this, your friend Gen Johnson got you the situation. If you resign it without sufficient cause—you may forfeit his friendship…” Whatever Sheets’ concerns were, it appears he took his mother’s words to heart. Whether it was out of a sense of personal loyalty, an eye for his own advancement, or a desire to maintain the officer’s pay that helped support his mother, Sheets stuck by his general’s side. “He was so devoted to me,” Johnson later recalled, “that my affection for him was like that of a father for his son.”

Sheets proved himself an asset to Johnson and his division. “Although a boy,” recounted Johnson, Sheets’ “judgment was well matured for one so young. He was brave, intelligent, and faithful, and made a most efficient staff officer. His handsome face, his pleasing manners, and his general intelligence made him a great favorite in the division.”

The young aide even left a lasting impression on Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, then commanding the Union 14th Corps. Johnson quoted Thomas as saying “That is a very intelligent aide you have. He delivered your message as correctly as if it had been written down, and he seemed to have an intelligent, comprehensive view of your position, as well as the character and size of the force opposed to you. I was impressed with his manliness and self-possession.”

That Sheets enjoyed the esteem and trust of his superior officers is further attested to in the official records, which show the teen playing a crucial role during the pivotal Tullahoma Campaign. In Col. Thomas E. Rose’s report of the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry’s movements during the June 1863 Battle of Liberty Gap, he recounted that Sheets “piloted” his regiment into position to execute a successful flank attack upon the Confederate forces.

That is a very intelligent aide you have. He delivered your message as correctly as if it had been written down, and he seemed to have an intelligent, comprehensive view of your position, as well as the character and size of the force opposed to you. I was impressed with his manliness and self-possession

— Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas

At Chickamauga, Johnson’s division once again found itself in a critical position on the battlefield. On Sept. 20, 1863, the second day of the conflict, it was part of the last-ditch stand that helped save the Army of the Cumberland from annihilation.

During this desperate fighting, Sheets was struck down in a hail of canister or grapeshot that instantly killed both him and the horse on which he was riding. A fellow lieutenant, William N. Williams of the 6th Indiana Infantry, saw Sheets “laying on the ground dead, he being Killed by a Cannonball in the Breast, taking away part of his Shoulder.” He was about 18 years old.

Comrades buried Sheets where he fell. Many of the federal dead from Chickamauga were later reinterred at Chattanooga National Cemetery. If workers disinterred and reburied his remains there, the site is likely unmarked.

The loss of Sheets deeply affected Brig. Gen. Johnson. “His death was a great loss to me, officially and socially,” he lamented, “for in life he was always with me.”

Brigadier Gen. William McKee Dunn, an aide to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and brother of Col. David Maxwell Dunn of the 29th, eulogized “the brave boy-lieutenant” in his memoir: “Poor Frank Sheets, cruelly slain in the comeliness and promise of his youth! He had been reared as their son by Mr. and Mrs. Tilton, was the playmate and companion of my children, and as I write these lines his warm young blood seems almost to spurt upon my hand.”

References: Manius Buchanan, letter to Emma W. Childs, Spared & Shared; Johnson, A Soldier’s Reminiscences in Peace and War; Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass; Dodge, History of the Old Second Division, Army of the Cumberland; 1860 US Federal Census, National Archives; Diane Perrine Coon, “Southeastern Indiana’s Underground Railroad Routes and Operations,” National Park Service; Military Service Records, National Archives; Civil War Widows’ Pension Files, National Archives; Obreiter, The Seventy-Seventh Pennsylvania at Shiloh: History of the Regiment; Woolen, William McKee Dunn, Brigadier-General, U.S.A.: A Memoir.

Brendan C. Hamilton is an Associate Editor for Irish in the American Civil War (irishamericancivilwar.com). He lives in Indianapolis, Ind.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.