By Kurt Luther

Most photo sleuths focus their attention on the subject of a Civil War portrait. This makes sense, as identifying the subject is typically the primary goal. Furthermore, the subject per se can offer a wealth of clues for identification, from facial features, to uniforms and insignia, to weapons and equipment.

However, the foreground and background elements surrounding the subject of a Civil War photo can also reveal critical information to aid the photo sleuth. Recent articles have discussed the research insights provided by studio props (see “Jeff. Davis and the South!,” MI, Spring 2023) and even flooring patterns (see “The 10th New York Cavalry at Gettysburg,” MI, Winter 2021).

Chief among these secondary clues are the painted backdrops employed by many 19th century studios. Adam Fleischer’s invaluable MI column “Behind the Backdrop” regularly illustrates how painted backdrops can serve as research tools in identifying both soldiers and photographers. When all other paths have been exhausted, analyzing painted backdrops can turn a dead end into a fresh start.

Challenges and opportunities in backdrop research

The specific research questions that painted backdrops can help to answer are myriad. If a photo lacks a photographer’s identification scratched on a hard image or printed on the backmark of a carte de visite, a backdrop can help identify the studio name and location in several ways. Some backdrops, such as the famous “Benton Barracks” scene linked to Enoch Long’s studio (see MI, May/June 2012 and Winter 2016), are instantly identifiable to a specific photographer. In other cases, the photographer associated with the backdrop may be unknown. But by locating multiple examples featuring identified subjects, a probable studio location and date range can be inferred by cross-referencing the service records of the pictured soldiers.

Once a backdrop is dated and located, the photo sleuth can employ similar techniques to identify unknown soldiers. A studio located in a small town suggests the soldier may have lived nearby or traveled there from a reasonable distance to muster in with his company. Follow-up research can identify which companies were recruited from that town and which soldiers listed it as a residence. The service records of identified soldiers photographed with the backdrop can also suggest specific regiments of which the mystery soldier may have been a member.

Unfortunately, these backdrop research techniques, while promising, are currently difficult to put into practice. One challenge is that there is no definitive reference mapping painted backdrops to specific photographers or studios. Researchers, collectors and dealers rely on their experience to recognize and identify backdrops, but, typically, only the most common ones are widely recognized, with others limited to the individual’s specialized interests. Another, related barrier is that no large public database or archive of photos with painted backdrops exists, so finding examples to compare is difficult. Finally, outside of MI’s archives, there is relatively little published research on painted backdrops, leading to a wide range of theories about even basic topics, such as how they were produced and how unique each backdrop is.

Introducing Backdrop Explorer

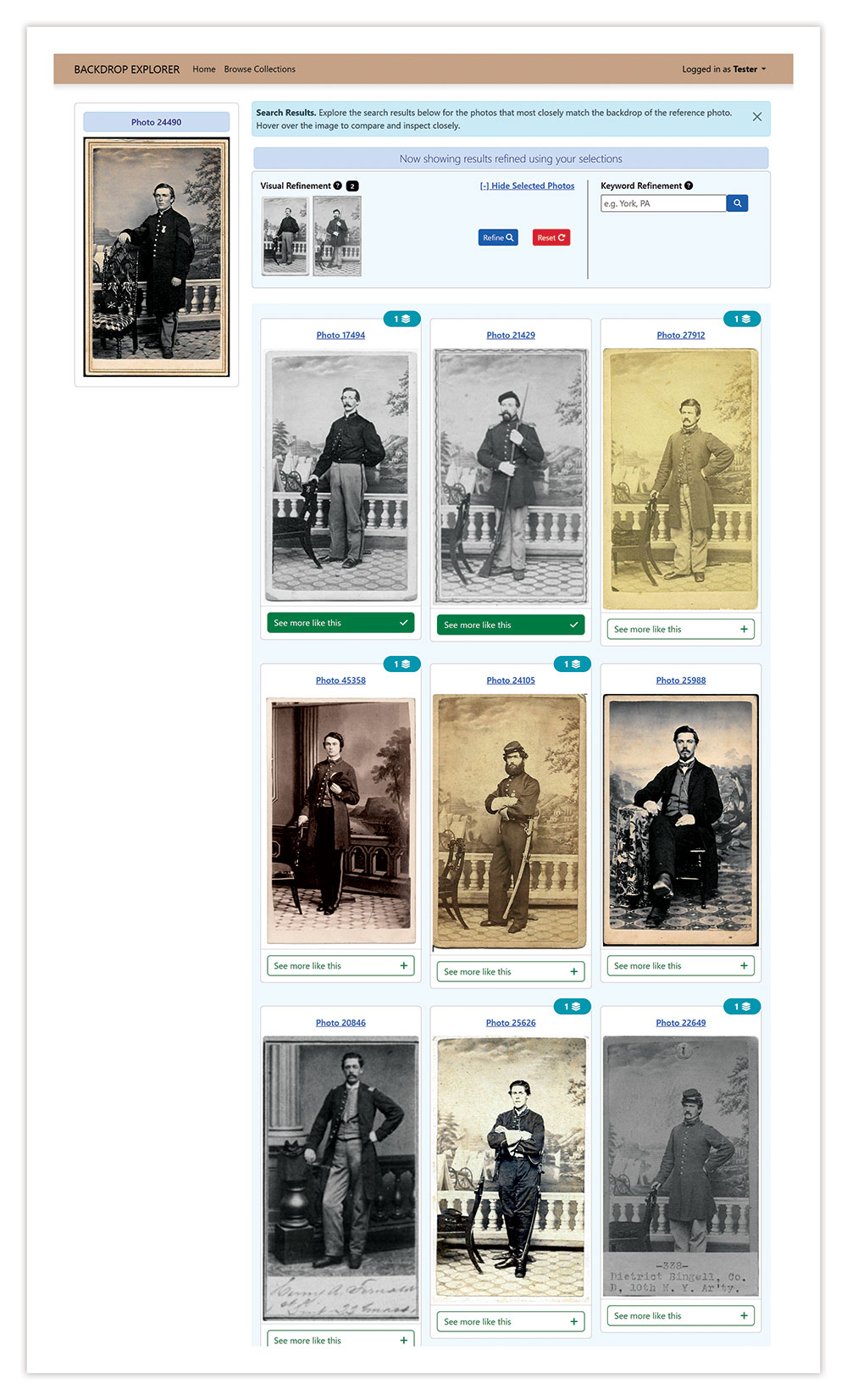

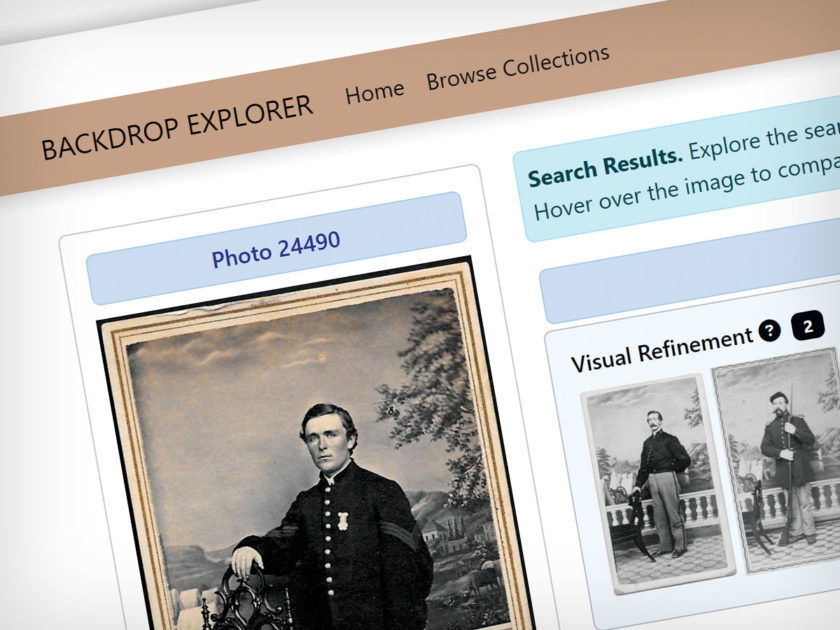

Given this remarkable but unfulfilled potential, our team at Virginia Tech, led by graduate students Vikram Mohanty and Jude Lim, has created a new software tool, Backdrop Explorer, to help photo sleuths conduct research on painted backdrops in Civil War-era photos. Backdrop Explorer has three important, interconnected features. First, it provides a reference database of photos with painted backdrops. Backdrop Explorer is built atop the digital archives of Civil War Photo Sleuth, our free website that includes nearly 50,000 searchable photos of Civil War-era soldiers and civilians. While CWPS combines human expertise and AI to identify a Civil War photo’s subject, as we will see, Backdrop Explorer adopts a similar user experience but focuses on backgrounds.

AI-supported searching and refining

The second feature of Backdrop Explorer uses a type of artificial intelligence (AI) called computer vision to help users discover and identify photos with painted backdrops. To discover photos with painted backdrops, the software automatically classifies which photos in the CWPS database have painted backdrops, and shows only those in search results. Of about 50,000 Civil War photos in the database, the classifier found about 8,500 that contain painted backdrops.

To identify backdrops, Backdrop Explorer allows users to provide a photo of interest, and the software automatically finds photos with similar-looking backgrounds and displays those results. The user first uploads their photo of interest to CWPS and provides any information they already have about the backdrop, including a name, description, photographer name, and studio location. Most users will not have this information. But in case they do, they can include it to help future researchers. Then the software uses a technique called masking to automatically remove the soldier from the photo and analyze only the background imagery. It compares all photos in the database and returns the top 1,000 most-similar results, ranked by visual similarity to the user’s photo.

At this point, the user may already see some matching backdrops in the first few search results. However, if not, the user can improve the search results by teaching the AI exactly what they want to see, a process called refining. To do this, the user can click the “Show more like this” button on search results with backdrops that are identical, or just similar, to their mystery photo. For example, if the mystery backdrop has an American flag in it, the user can select search results that also contain American flags, even if they are clearly different backdrops. The AI will learn from this user feedback and the refined results will be more likely to contain flags.

Users can combine these visual searches with text-based keyword searches. For example, a user could type the search keyword “cannon” or “Nashville” to narrow down results to only those photos with backdrops containing cannon, or with studios located in Music City, respectively. However, these text searches rely on previous users providing correct descriptions, which brings us to the third major feature of Backdrop Explorer: collections.

Crowdsourced collections

Collections are crowdsourced groupings of Civil War photos with similar backdrops. When a user finds another photo with a similar backdrop, both photos can be placed in the same group, known as a “collection.” Each collection can have a user-provided name, description, and photographer name and location. For example, a “Palm Tree Backdrop” collection (see MI, Winter 2022) might list Norman Erastus Allen as the photographer; Jackson, Mich., as the location; and include various examples of the backdrop featuring Michigan infantrymen and sharpshooters. To start, we have seeded the collections with roughly 150 photos containing around 40 unique backdrops drawn from Adam Fleischer’s columns, other MI articles, and our own research. Over time, as more people use Backdrop Explorer, we hope that the collections will grow to become a comprehensive, searchable reference linking together hundreds of backdrop names, example photos, and photographer details.

First feedback and next steps

So how well does Backdrop Explorer work? To find out, we tested the software with nine participants ranging from photo sleuthing novices to experienced collectors and researchers. We asked them about how they typically research Civil War painted backdrops and then instructed them to try using Backdrop Explorer with a series of photos we provided. Overall, participants enjoyed using the software and were successful in identifying backdrops. Furthermore, all participants preferred the visual search features to the traditional, text-based search. One participant noted how the computer vision caught backdrop similarities that he might have overlooked: “What really impressed me the most was that it did catch some of what might appear initially as a different background, but what’s, in reality, the same background.” Another participant noted that the algorithm matched other background elements: “Beyond the backdrop, you were able to see the same chair or, as I noted, you could see the same flooring. So, you know, I think it’s useful for more than just backdrops.”

Our efforts with Backdrop Explorer are just beginning. For the future, we are working on integrating the software into the CWPS website and launching it publicly. A project recently completed by graduate student Terryl Dodson compared several computer vision algorithms to determine which works best for Civil War backdrops and improve the software’s performance. We are also collaborating with collector Michael Helfrich, who has amassed a digital collection of hundreds of carefully annotated photos of Civil War backdrops, to improve our reference database and taxonomy. Eventually, our vision is that Backdrop Explorer will not only aid countless photo sleuths in identifying soldiers and photographers, but also help the community to answer more fundamental questions about painted backdrops and their role in Civil War photography.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Introducing Backdrop Explorer, a New Civil War Photo Sleuth Feature”

Comments are closed.