By Paul Bolcik

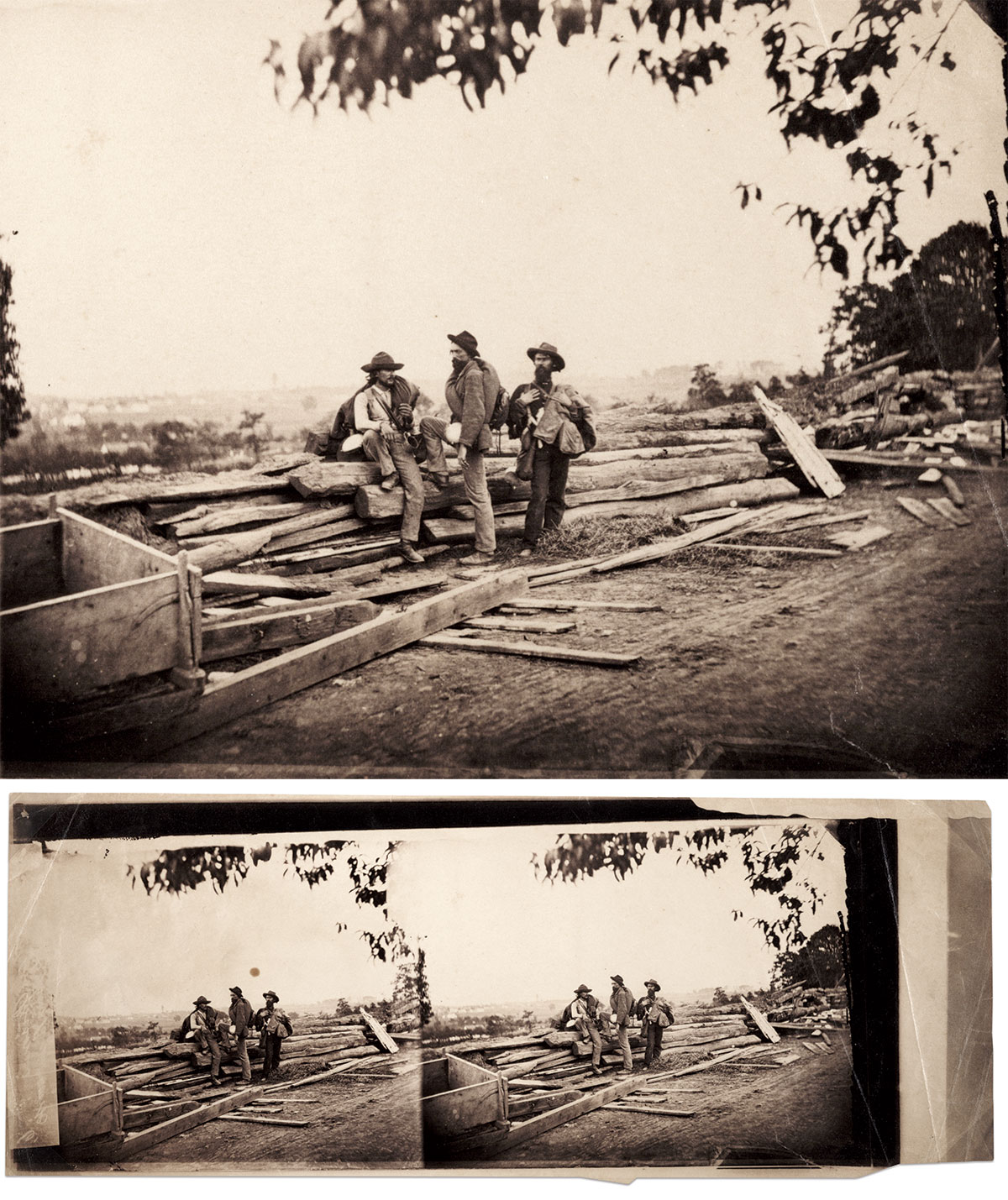

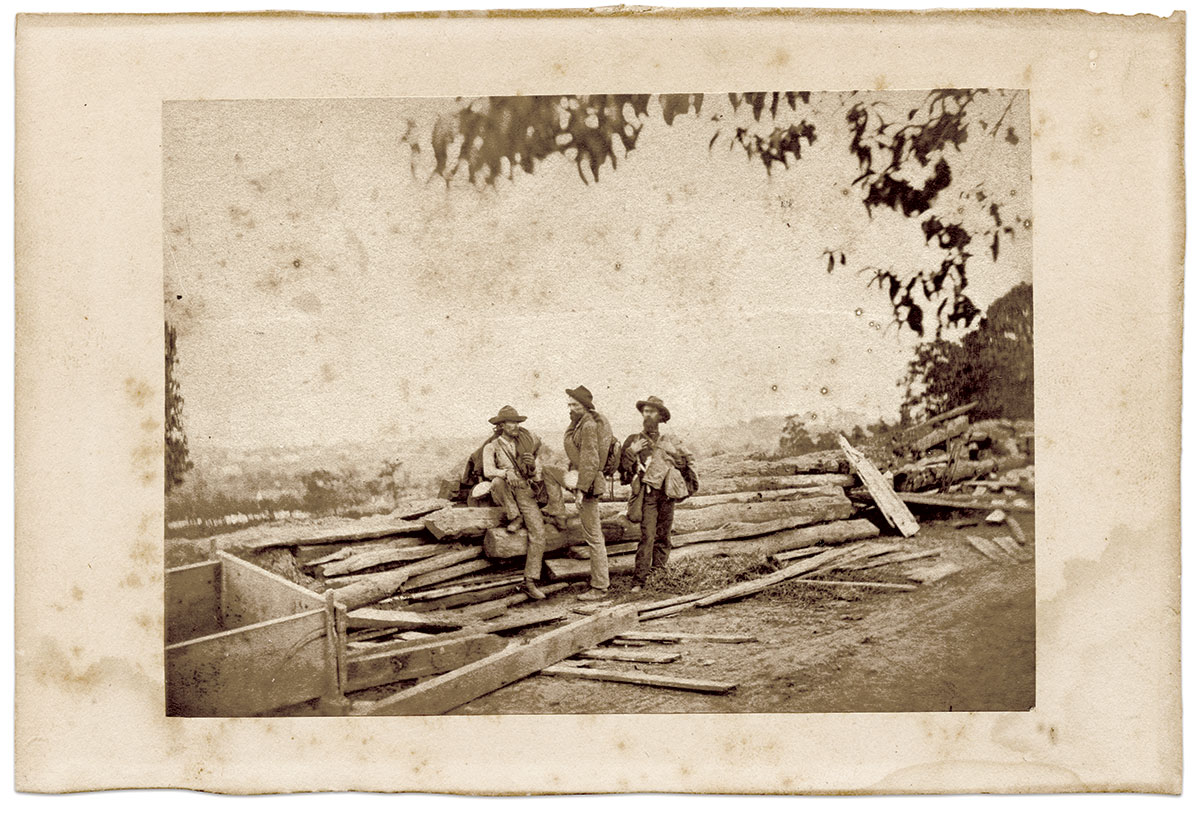

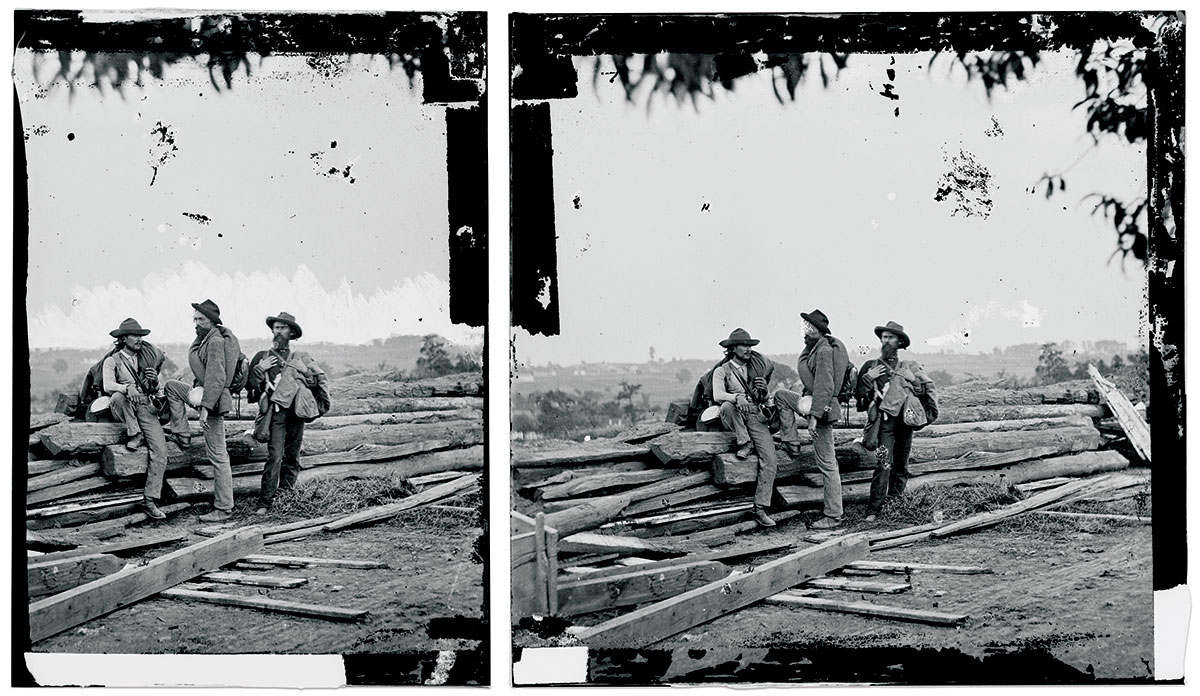

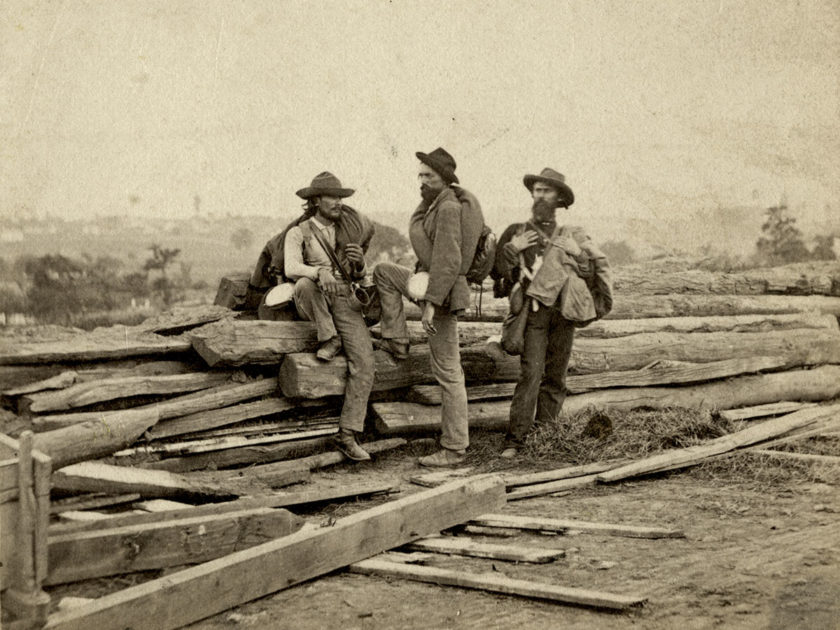

Few war photographs rise to the level of iconic. This singular image created by Mathew Brady’s team of photographers in the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg ranks among them. The vision of three soldiers standing near a pile of lumber and a worn wagon is representative of the most turbulent period in American history.

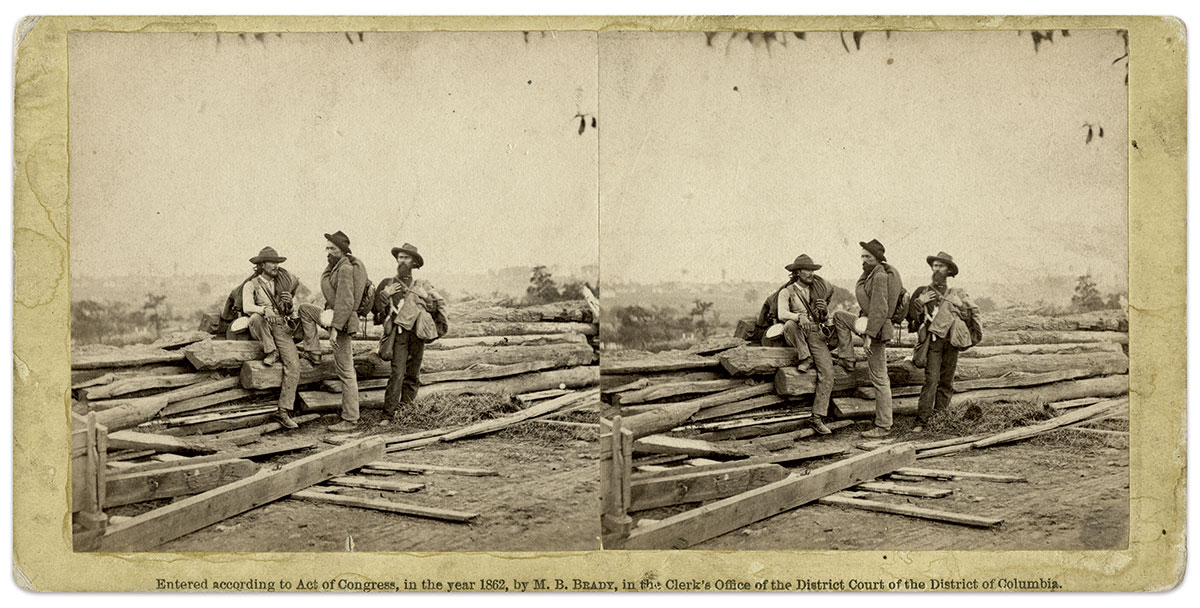

Little is known about the image. Scratched into the surface of one half of the stereo glass negative is “rebel prisoners behind their breastwork.”

This barebones caption leaves a vast and almost insurmountable void of details.

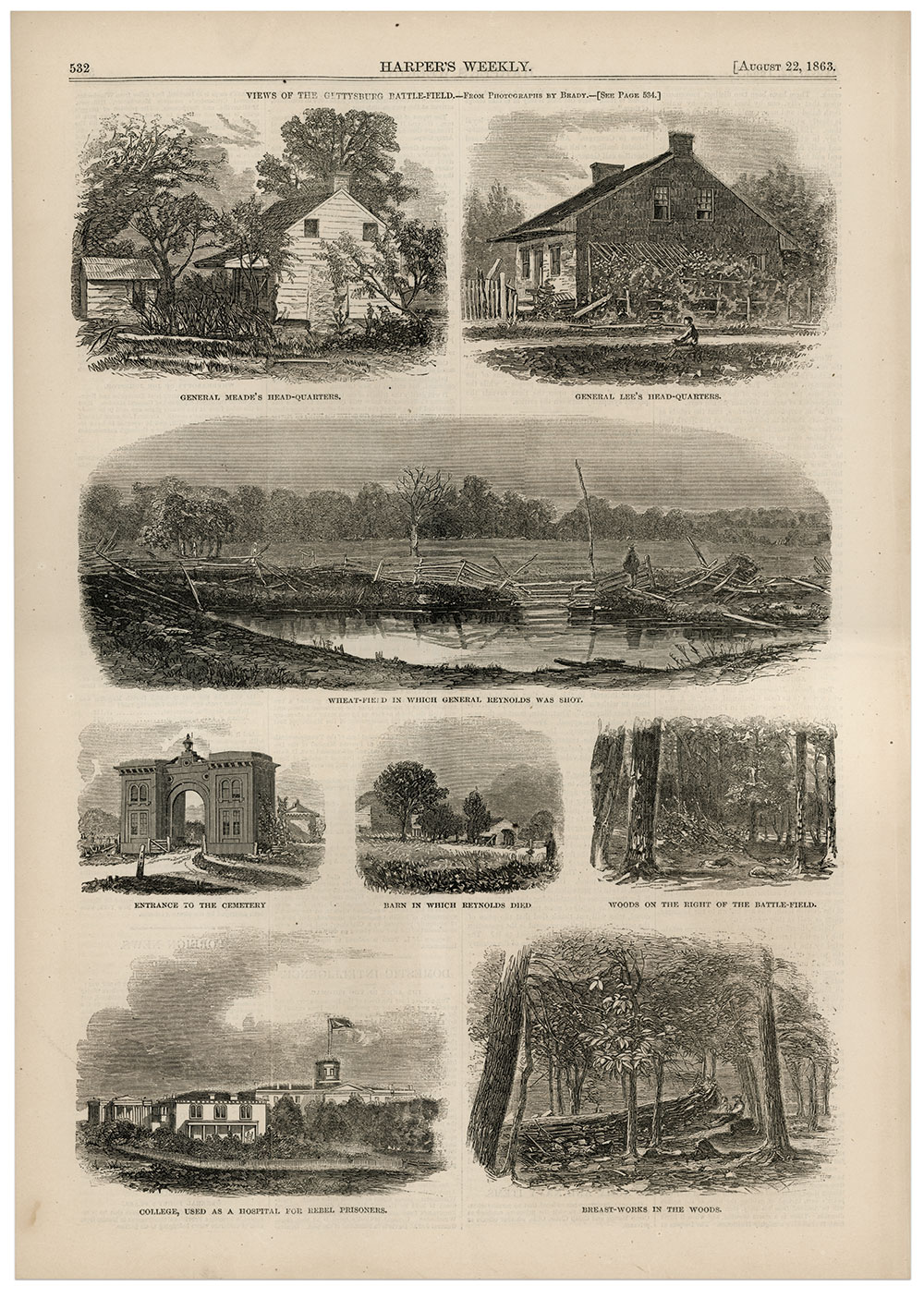

This image did not immediately capture the public’s imagination. The editors of the popular illustrated newspaper Harper’s Weekly failed to include it in the first group of 11 of Brady’s Gettysburg photographs published as engravings in the Aug. 22, 1863, issue. The images they selected—the hero John Burns, the location of the death of Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, panoramic views and prominent buildings—suggests they prioritized news value over aesthetics.

The public first glimpsed the Confederate trio a few weeks after they posed. According to a report in the August 7 edition of the New York Times, “Brady has published a series of fourteen photographic views of Gettysburgh, which has now become an historic place, and of its vicinity; the battle grounds, the spot where Reynolds fell, and other localities of interest. The views are artistically excellent, of course correct; and the series form an interesting and valuable collection.” Brigadier General Lucius Fairchild purchased a complete set, all stereo cards, in the summer of 1863. He had suffered a wound and amputation of his arm in action with his 2nd Wisconsin Infantry and the Iron Brigade in the battle.

Tracing the publication of the photograph

In 1894, about three decades after Gettysburg and 20 years after the federal government purchased Brady’s negatives, the photograph appeared in The Memorial War Book. In a statement before the preface, author George Forrester Williams (1837-1920) explained that the 2,000 images were selected from more than 6,000 glass negatives by Brady and Gardner. Williams also noted an exclusive arrangement to publish the images with The War Photograph and Exhibition Company of Hartford, Conn. The firm had reissued the photographs a few years earlier in anticipation of renewed public interest in the war during the 25th anniversary. The company’s bet proved correct, and Williams followed suit with his book.

Technology played a key role in the timing of the book’s publication. Recent advances in duplication processes allowed for more faithful reproductions of original photographs than traditional engravings. These photographic reproductions achieved an authenticity that engravings on wood and metal could not.

Another important factor: economics. A single-volume book of 2,000 wartime images was more affordable than purchasing the same number of stereoscopic views. The book was also available for purchase in 30 parts, each consisting of dozens of images.

Williams was no stranger to printing, writing and photo selection. Orphaned as a teenager, he got his start in the world as a compositor for the New York Times, setting type for the newspaper. One night, after the editor had left for the day, Williams wrote a breaking news story. An impressed editor promptly moved him from the composing room to the editorial department.

Williams traded his pen for a musket when the war began. He joined the ranks of Duryéa’s Zouaves, which mustered for federal service as the 5th New York Infantry. Over the next three years, he advanced to sergeant, and suffered wounds at Malvern Hill and The Wilderness. In the summer of 1864, he left the army and became a Times war correspondent in Virginia. After the war, he continued his rise through the Times newsroom, serving at one point as managing editor. His wartime illustrated memoirs, Bullet and Shell, hit bookstores in 1883. He dedicated it to his comrades in arms in the federal armies.

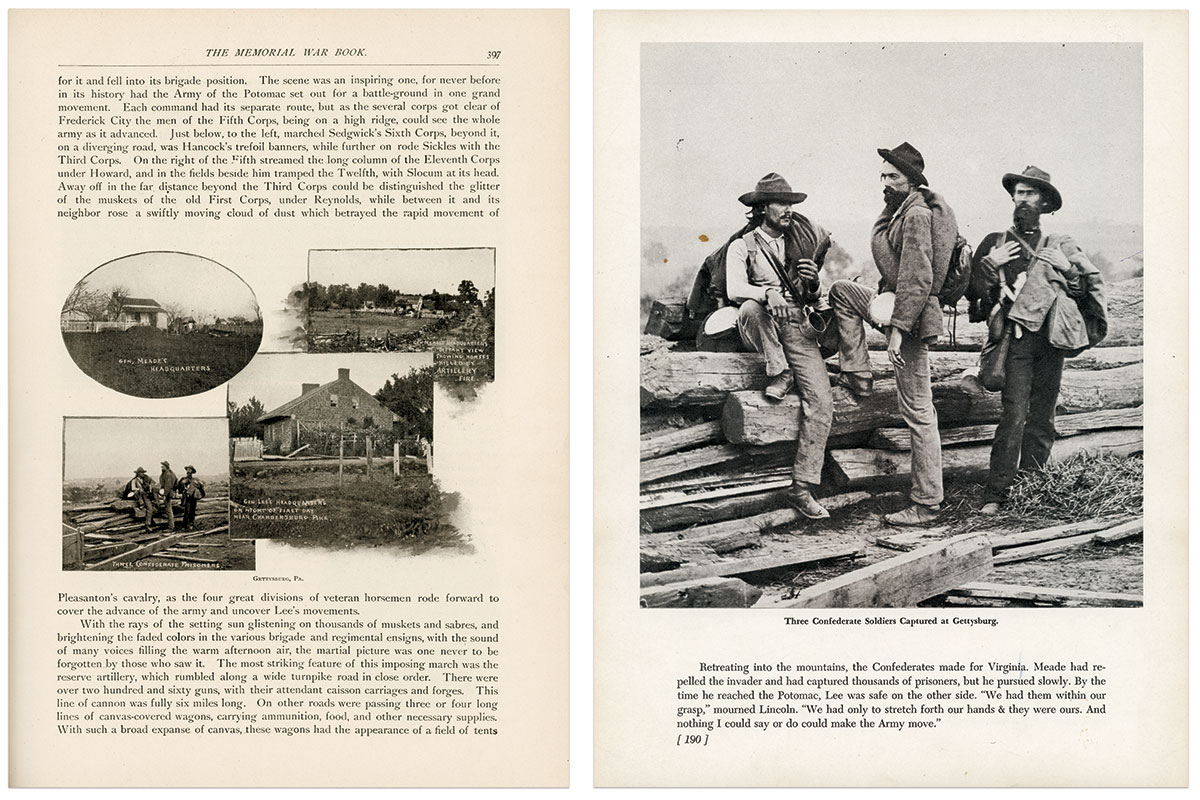

Eleven years later, Williams’ The Memorial War Book expanded on his memoirs by adding an array of personal narratives to humanize the war. His selection of illustrations, from generals to photographs of soldiers and officers in the field, reinforced his narrative. On page 397 can be found the prisoners photograph, reproduced in a collage with a view of Meade’s headquarters and one of Lee’s at Gettysburg. It is labeled “Three Confederate Prisoners.” Though no caption accompanies the photograph, Williams’ respectful references to the Southern soldier as a worthy adversary casts the prisoners in a positive light.

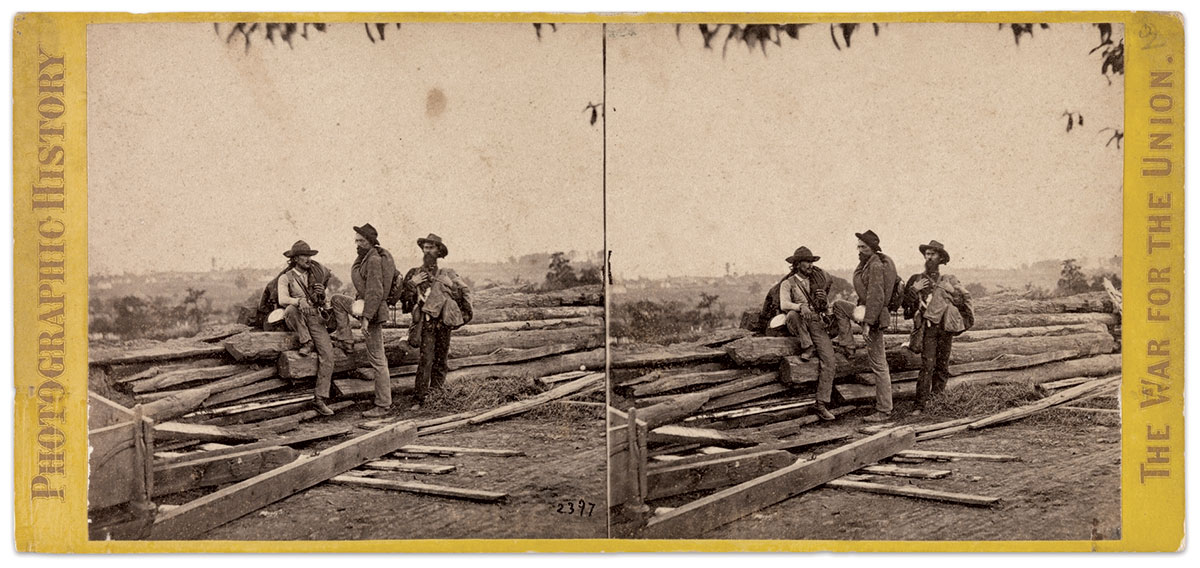

In 1911, as aging veterans gathered for reunions to commemorate the war’s semicentennial, Francis Trevelyan Miller (1877-1959) published the image as one of 3,800 photographs in his landmark 10-volume series, The Photographic History of the Civil War. It appears in Volume One. Miller’s team played it small, about a quarter page, and added a caption that reinforces the narrative of the heroic and hard-fighting Southern soldier, often repeated in the 20th century. It reads, in part, “they marched and fought in any garb they were fortunate enough to secure and were glad to carry with them the blankets which would enable them to snatch some rest at night.” The caption provides no additional detail about the men or location.

In conjunction with the rollout of Miller’s Photographic History, several newspapers, including The Buffalo News, The Minneapolis Journal and The Sioux City Journal, dedicated portions of their Sunday section to showcasing selected images in weekly installments as early as May 1911. None published the photograph of three Confederate prisoners.

This same year, The Boston Globe launched “The War Day by Day.” This series began on Feb. 11, 1911, the 50th anniversary of President-elect Lincoln’s departure from his home in Springfield, Ill., to the nation’s capital, with a promise to “unfold for its readers the story of that tragic period day by day so that they can follow its dramatic occurrences as if they were living in the historic days of ’61.” Four months into the series, on June 7, the photo of the three prisoners illustrated a look at the fighting forces of the South by London Times war correspondent William H. Russell. The Globe staff titled the photograph “Types of the South’s Fighting Men.”

In 1953, with the centennial of the war on the horizon, the image appeared in another landmark book, Divided We Fought. In the foreword, editor David Herbert Donald (1920-2009) acknowledged an ancestral connection to Miller’s Photographic History and the need for a single volume of collected images with modern printing technologies. Donald’s picture editors selected about 331 photographs and 96 wartime illustrations. The trio of rebels made the cut. Cropped tightly around the figures and captioned “Three Confederate Soldiers Captured at Gettysburg,” it occupies a full page.

Credit for including the image in Divided We Fought belongs to Donald’s picture editors, Hirst D. Milhollen and Donald H. Mugridge. Both men worked for the Library of Congress. Milhollen, a Virginia-born fine artist, led the prints and photographs division. Mugridge, an Illinois native, served as a specialist in American history. Their names are included in the “About this item” section of the Library’s online page for the image.

Seven years later, on the eve of centennial commemorations, The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War followed in the footsteps of Miller and Donald. Editor in Charge Richard M. Ketchum (1922-2012), Senior Editor Bruce Catton (1899-1978) and the editors of American Heritage magazine included the image, tightly cropped as it appeared in Divided We Fought. The caption is similar in spirit to Miller: “Their capture at Gettysburg ended the fighting days of these three lean, tough Confederate soldiers.”

Publication by Miller, Donald and Ketchum propelled the image on its path to the recognition it has today. Other books followed suit in the decades that followed.

Probing the origin of the image

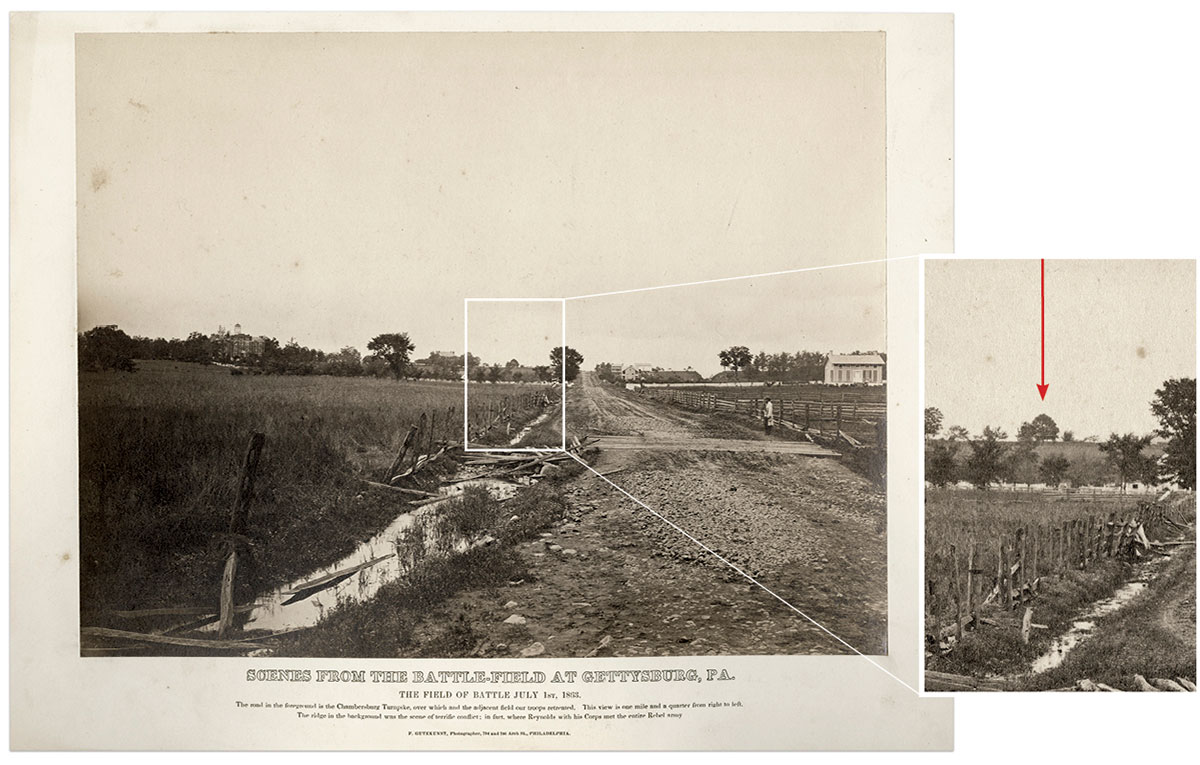

William A. Frassanito’s study of Gettysburg photographs provided the first significant details about the image’s origins. In his 1975 book, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time, Frassanito employed groundbreaking methodology to locate the spot where the men stood, and he estimated the date they posed: July 15, 1863.

Frassanito’s 1995 book, Early Photography at Gettysburg, added that Brady photographers David B. Woodbury and Anthony Berger were present in Gettysburg on or about July 8-9, 1863. The source for this information, Alexander Gardner, a former Brady employee turned independent photographer, observed the two men as he headed from Gettysburg to Washington. Gardner scooped Brady’s team, bringing back the first photographs of the battlefield.

Gardner’s eyewitness account raises questions about the July 15 estimated date of the image. Did Woodbury and Berger, armed with government-issued passes, follow on the heels of the Army of the Potomac as it entered Gettysburg? Might they have been present in the rear areas as the battle unfolded?

Whenever they arrived, Woodbury and Berger would have likely gone into production immediately upon their arrival, fueled by a sense of urgency and with the implicit blessing of Brady, who followed and arrived on the scene by July 15.

Investigating the scene and the soldiers

Frassanito’s scholarship provided the foundation upon which students of the Civil War have launched investigations to explain the imagery in the photograph.

These efforts have been aided in recent times with the discovery of two albumen prints.

One, held by The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, is described in its online entry as a full stereo. It establishes that Brady’s original stereo glass negatives were 4-by-10 inches, larger than the 3-by-3 inch copy negatives in the Library of Congress. Etched into the plate is the description, “rebel prisoners behind their breastwork,” and an identification number. The wider crop includes more detail of the wagon on the left of the frame and the lumber on the right.

The other print, in the Paul Russinoff Collection, is a similar crop. It includes more detail of the lumber on the right side of the frame, and the lack of the inscription on the left provides an unfettered view of the wagon and area above it.

How did the woodpile come to exist?

The origin of the lumber, logs and other debris described as breastworks is an unfilled void.

Frassanito, in a letter to me dated Dec. 27, 2013, noted, “I too have long been puzzled by the odd collection of lumber at that site. But regardless of the lumber’s origins, the specific site and approximate date (on about July 15, 1863) are firmly established. So the mystery concerning the lumber continues…”

The lumber is an assortment of notched logs, planks, fence rails and other wood scraps. What appears to be two square roof support beams are visible on the left. The wood planks below it may have been placed to keep the beams from touching the soil—an indication that they were valuable and could be reused at some future time.

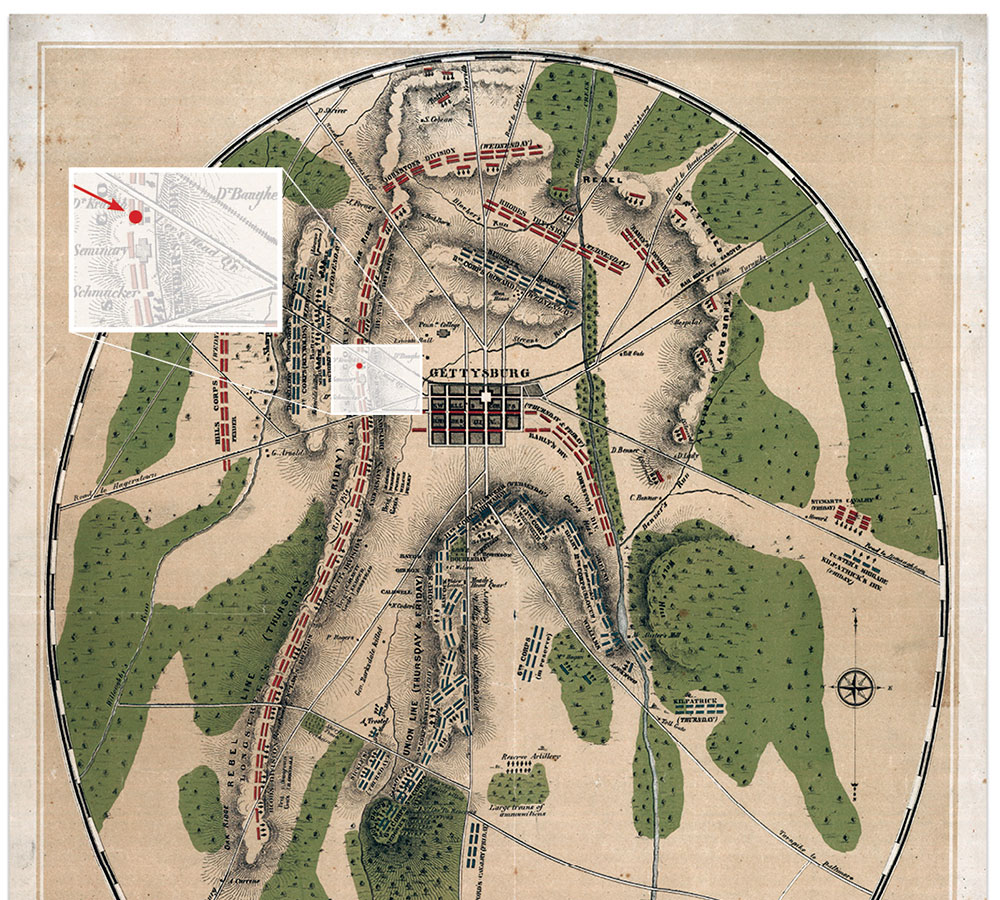

The photograph spot is located about 100 yards north of the Seminary grounds.

Several theories might explain the existence of the lumber prior to the battle.

A convenient spot for unwanted lumber. Located in the rear or west side of the Lutheran Seminary property, it might have been used as firewood to keep Seminary pupils warm during cold weather months. Union Brig. Gen. Gabriel Paul’s Brigade constructed breastworks on the morning of July 1 in this vicinity.

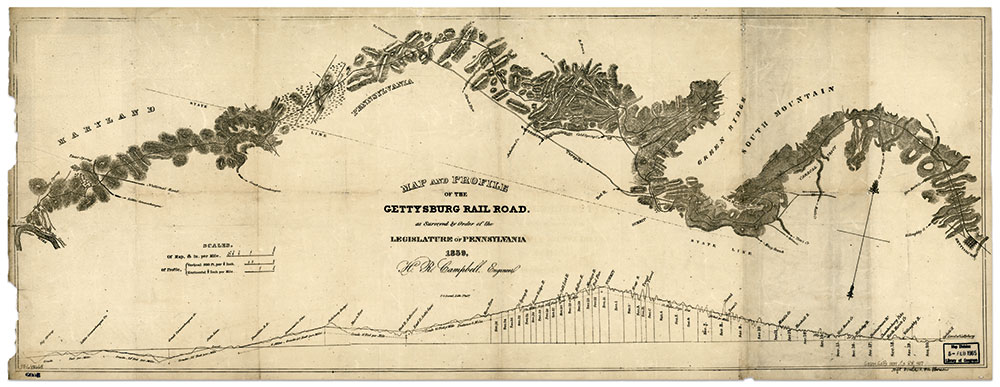

Leftover construction materials from the Gettysburg “Tapeworm” Railroad. A portion of the wood may be the remains of temporary structures built to house workers building the railroad, a short-lived and incomplete project (1836-39) to connect Gettysburg to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal along the Potomac River supported by influential U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens. It resulted in two unfinished railroad cuts with battlefield connections: Oak Ridge (known as Seminary Ridge after the fighting) and McPherson’s Ridge.

Remains of an abandoned shoe factory. An 1858 map of Adams County, (also known as the Converse map) based on an 1856-57 survey, depicts a shoe manufacturing shop some 150-200 yards west of the spot where the three Confederates posed. It is not known if this shoe shop was still standing on July 1.

The lumber might not have been present at the photo spot prior to the battle. We know this because of the postwar memoirs of 2nd Lt. James P. Alcorn of Battery B, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, also known as Cooper’s Battery. On the morning of July 2, he buried his brother, Alexander, on or near the photo spot. This suggests no construction of rebel breastworks had yet to begin in the area.

Union Maj. Abner R. Small described the construction of breastworks on the morning of July 1 by his regiment, the 16th Maine Infantry, part of the First Brigade, Second Division, First Army Corps: “Our brigade went around to the western face of the Lutheran seminary, and there we threw up a barricade of fence rails and anything else that was handy. The barricade took the shape of a crescent, bending to the west.”

No photographic record of the breastworks is known to exist.

Confederates overran the position that afternoon. It’s probable that they dismantled part or all of the barricade after they occupied the ground and carried most of the lumber to the east side of the Seminary lawn to construct artillery battery positions. They most likely moved the lumber to cover a hole blasted through the stone wall, either by their own artillery fire from the July 1 fighting, or the hole may have been created by Union artillerymen to escape the rebel onslaught on that late afternoon.

Another scenario involves the last Confederates on the spot during active fighting. According to post-battle maps, Capt. William P. Carter’s Company, Virginia Light Artillery, also known as the King William (County) Artillery, occupied the position on July 3 and part of July 4. Carter’s men might have continued the work begun by their comrades at midday on July 2, or they may have built the breastworks from scratch, transporting lumber from the crescent described by Maj. Small, and/or scrounging up wood from the vicinity.

The expanded albumen print reinforces the scenario that the Virginia artillerists are responsible for the arrangement of the lumber seen in the image. It has the hallmarks of a temporary protective wall. Of note is an area on the far-right side of the print where the timber ends and a smoother, textured surface begins. This shows the stone wall constructed after the completion of the Lutheran Seminary in 1832.

There may never be an airtight explanation of the origin of the lumber material, and the movement of it before, during and after the battle.

Who are the prisoners?

The most prominent void is the identity of the prisoners. During the post-war period, as the veterans aged and debated their places in history at reunions, monument dedication ceremonies and elsewhere, no one stepped forward to claim they were one of the three men in the image. No veteran publicly recognized them as comrades.

This is curious, considering the wide circulation of the image in the media.

Since the last Civil War veterans passed from the scene, the quest to name the trio has consumed uncounted research time, speculations and claims. One source suggests the men hailed from Louisiana; another from North Carolina.

“One might argue that the anonymity of these Confederates contributes to the iconic status of the image. They could be any Confederate soldier representative of the Southern military volunteer at Gettysburg, the Eastern Theater of operations and the Civil War.”

Many believe they were stragglers captured during mop-up operations after the battle, a suggestion made by Frassanito in Journey in Time.

One might argue that the anonymity of these Confederates contributes to the iconic status of the image. They could be any Confederate soldier representative of the Southern military volunteer at Gettysburg, the Eastern Theater of operations and the Civil War.

Basic questions about them remain unanswered. Why were they featured in the image? Where exactly did they come from and where were they headed? Who are they?

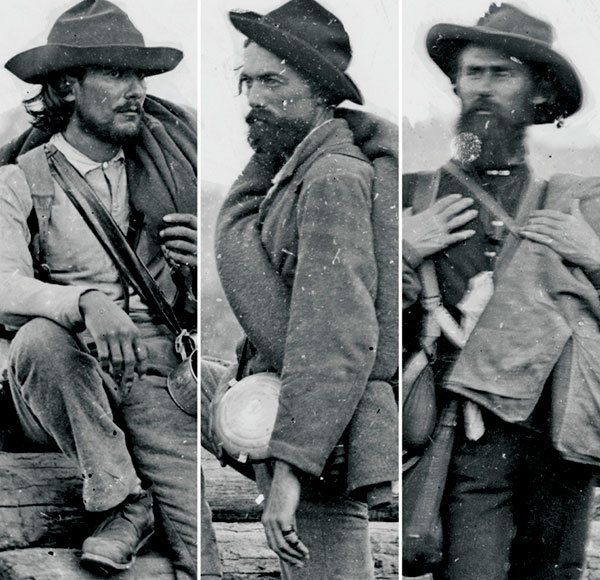

An examination of the soldiers, the clothing they wore and the accouterments they carry offers contradictory information. They are well attired and do not fit the persona of the shoeless ragged rebel. The caption writer for Miller’s Photographic History concocted a tale to fit the shoes worn by the trio into the narrative of the noble Confederate volunteer: “Their shoes—perhaps taken in sheer necessity from the dead on the field—worn and dusty as we see them—were unquestionably the envy of many of their less fortunate comrades.”

Their clothing suggests no evidence of rank, leading one to believe they were enlisted men. This fits the narrative of captured stragglers. Is it possible that they were officers? The postwar recollections of Dr. Simon Baruch (1840-1921) reveals that a soldier’s rank may not have been immediately obvious. A Polish immigrant who served as a Confederate surgeon and the father of 20th century financier and presidential advisor Bernard Baruch, he described his Gettysburg experience in the December 1914 issue of Confederate Veteran. Ordered to remain with the wounded, Surg. Baruch “hastily donned my gray coat and green sash” on the approach of the Union cavalrymen to whom he surrendered soon after the battle ended. It is easy to imagine another scenario where Baruch (or any another officer) did not have time to dress in the uniform that indicated his rank. Baruch goes on to describe how, weeks later in prison at Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, “our uniforms had ceased to indicate our rank, and some of us wore civilian coats.”

The soldier to the left of the print wears shirtsleeves and a slouch hat. His coat or jacket is casually thrown over one shoulder. The canteen slung over the other shoulder, tin cup, overstuffed leather or tarred haversack to which a tin cup is tied with string and bedroll visible behind the canteen indicate he is well-provisioned. A knapsack is also visible.

The soldier in the center is the only one wearing his jacket, which is devoid of insignia. His knapsack appears full and his bedroll in immaculate condition. Another distinguishing characteristic is a piece of material wrapped around the left pinky finger that resembles a bandage. The material is secured on either end by bands composed of a dark, shiny substance.

The soldier standing on the right is dressed in dark trousers and shirt that contrast with his comrades. He carries a knapsack, two full haversacks, his jacket, a cloth bag and tin cup. An unknown item wrapped in or composed of light cloth is partly obscured by his jacket. If he has a bedroll, it is not visible. The contours of the crown of his hat are not smooth, which may be the result of blurriness, frayed material or perhaps a feather or other items tucked into the hatband.

Were they surgeons?

The visual information, the proximity of the site to the Seminary, which served as a hospital during and after the battle, and scholarship by historians led me to a hypothesis that the prisoners were medical men. Could they be surgeons or nurses?

Several items in the image point to a possible medical connection. The unusual contours of the haversack carried by the man on the left could be a surgeon’s kit. The object attached to the pinky finger of the man in the center could be some sort of pincushion or thread spool. The small bag carried by the man on the right could be for medical supplies and the oddly shaped item behind his coat could be bandages.

I shared my thoughts with Frassanito in November 2018. His reply, on November 24, stated, “In my opinion there is nothing about their uniforms that would even suggest that they were anything but privates in an infantry unit. The basic problem with your theory, since CS surgeons were the rank of Major and wore uniforms consistent with their rank—with the insignia of a Major on both their collars and their sleeves.”

Undeterred and mindful of Baruch’s recollections in Confederate Veteran, I turned to the late Gregory A. Coco’s award winning books, A Vast Sea of Misery (1988) and A Strange and Blighted Land (1995). The latter volume contains an appendix with names of C.S. and U.S. surgeons Coco believed stayed on the field treating wounded after the fighting. Perhaps one or all three of the men in the image are on Coco’s list.

I also considered the question of why Brady’s team selected them. Did the image result from a random encounter between photographers and prisoners? If so, the men might have been on the way to or from the Seminary to attend to patients.

Or perhaps the photographers planned to meet these particular prisoners because they were connected to a senior officer with name recognition. Among the high-ranking Confederates documented to have been in the Seminary hospital were Maj. Henry Kyd Douglas, Brig. Gen. James L. Kemper and Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble. I turned back to Coco’s list but was unable to make a direct connection between a surgeon and a senior officer.

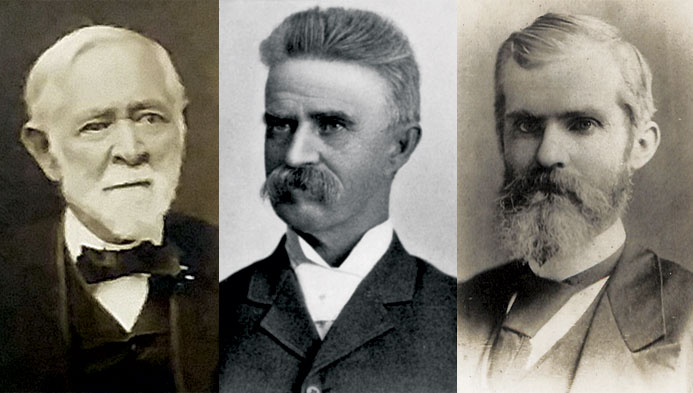

I searched the Internet for the names on Coco’s list of Confederate surgeons and assistant surgeons to learn more about their service and Gettysburg experience. I found postwar portraits for some, and a few bore resemblance to the three prisoners: Samuel Rush Sayers (1833-1914), a surgeon in the Stonewall Brigade who attended the amputation of Trimble’s shattered leg on July 4, William Maberry Strickler (1838-1908) of the 52nd Virginia Infantry and Brig. Gen. William “Extra Billy” Smith’s Brigade, and Harvey Black (1827-1888) of the 4th Virginia Infantry.

I uploaded these images to Civil War Photo Sleuth, which uses face recognition technology to rediscover lost identities in Civil War photographs. The likenesses of the three men in the famous image were also uploaded. The results of the comparison revealed no matches.

Perhaps Frassanito is correct in that they are Confederate privates.

Were they nurses?

After exhausting my research into surgeons and assistant surgeons, I considered the possibility that they may have been nurses, or enlisted men on detached duty as nurses.

This line of inquiry led me to Henry B. Blood (1835-1917), a figure who looms large in Coco’s books. A captain in the U.S. Volunteer Quartermaster Department, he and another officer were put in charge of cleanup operations after the fighting. They supervised burials and recovered government property left on the battlefield.

Blood recorded his activities in a ledger. His July 12, 1863, entry reads, “Took a squad of prisoners of war and went up to the Confederate Hospital to assist in cleaning up and to bury the dead. Found them in a suffering condition. Left ten prisoners for nurses. Thunder shower this afternoon.” The “Confederate Hospital” is a likely reference to the Seminary.

Connecting Blood’s statement, the location of the image and my observation that the men may have a medical connection leads to the possibility that the three prisoners may have been among the 10 nurses detailed by Capt. Blood.

If true, this might explain why they are dressed in enlisted men’s uniforms and are well supplied. The date mentioned by Blood, July 12, sits midway between Gardner’s report that Woodbury and Berger were in Gettysburg on July 8-9 and Brady’s arrival by July 15.

This theory also challenges Frassanito’s assertion that the men were simply stragglers gathered up during cleanup operations.

Conclusion

The void of details about the “rebel prisoners behind their breastwork” is as vast today as when the image first appeared in 1863. Almost no progress has been made on identifying the individuals or the pile of lumber behind them after publication in books by Miller, Donald, Ketchum and so many others.

What more can we learn about this famous image? Are unpublished portraits, letters, journals or other documents that hold the key to naming these men yet to be discovered?

The search continues.

Special thanks to Paul “Leon” Smith for obtaining documents from the Gettysburg National Park Service headquarters for this study, Cindy L. Small (Greg Coco’s widow) for reviewing Greg’s notes, William A. Frassanito, Tim Smith, Center for Civil War Photography President Bob Zeller, the National Civil War Medical Museum in Frederick, Md. Erik Davis for his research and perspectives, and National Park Service Ranger Melisa Miller of Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine.

References: Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 22, 1863; New York Times, Aug. 7, 1863; Email exchange with Tim Ream, Visual Materials Archivist, Wisconsin Historical Society, Feb. 28-March 1, 2023; Williams, The Memorial War Book; Miller, The Photographic History of the Civil War, Volume One; The Boston Globe, Feb. 11 and June 7, 1911; Donald, Divided We Fought; Baruch, Simon, “A Surgeon’s Story of Battle and Capture,” Confederate Veteran (December 1914); Alcorn, James P. “Recollections of the Battle of Gettysburg” transcribed by Jody Foster, Gettysburg National Military Park Library; Zeller, Bob, “Brady’s Gettysburg Stereographs Grow Bigger, Battlefield Photographer (December 2006).

Paul Bolcik of Rockville, Md., first contributed to Miltary Images in the November-December 1991 issue. He is the author of “William Walker: Nothing as it Seems” in The Daguerreian Annual 2012, the yearbook of The Daguerreian Society, and a co-author of “Confederates in Frederick: New insights on a famous photo” in the April 2018 issue of Battlefield Photographer, the official publication of the Center for Civil War Photography. He collects neither daguerreotypes nor Civil War images. Bolcik may be contacted at paul.bolcik@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

2 thoughts on “Three Confederate Prisoners at Gettysburg: Exploring the vast void of an iconic photograph”

Comments are closed.