By Charles T. Joyce

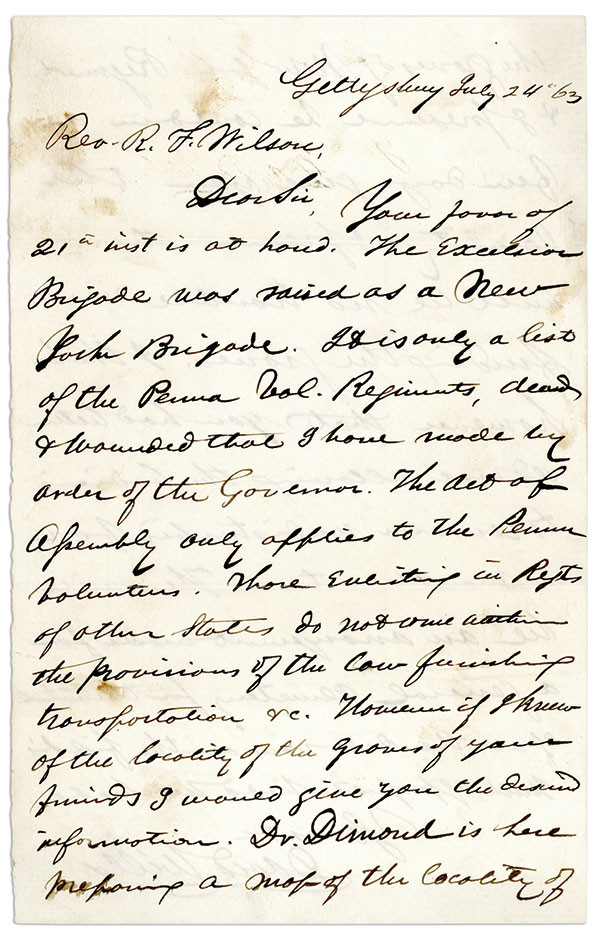

David Wills’ work with other state agents dispatched to Gettysburg by their governors to deal with their own dead convinced the young attorney that a less parochial approach was necessary. On July 24, 1863, the same day he wrote to Gov. Curtin suggesting the need for a common burial ground for Pennsylvanians, Wills penned a response to a Pittsburgh clergyman seeking to have the graves of several of his friends who had enlisted in Daniel Sickles’ New York Excelsior Brigade located and returned to their Allegheny County home. Wills advised that Pennsylvania’s offer for disinterment of the dead and escorted transport home did not apply to men who enlisted in other states.

However, Wills noted, Dr. Theodore Dimon, the agent of the Empire State, was “here preparing a map of the locality of the graves of New York Regiments & I presume he could in a few days give you the locality” of his friends’ remains. Wills advised the preacher, though, that it might be better to allow the bodies “to remain undisturbed for a month or two. There will be an arrangement made for a general cemetery for the burial of all the dead now on the fields with appropriate head markers, &c.”

Most historians now believe it was Dimon who likely first suggested to Wills the idea of a national cemetery funded and supported by all of the states with regiments at Gettysburg. Wills’ contemporaneous letter to the Governor urged prompt approval of this concept and noted that Cemetery Hill—in particular its fiercely contested eastern slope—was “the spot, above all others, for the honorable burial of the dead who have fallen on these fields.” However, by the time Wills received authority to purchase the land he was chagrined to discover it had already been bought by fellow Gettysburg barrister David McConaughy.

The Chairman of the Board of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery, McConaughy’s plans for the land adjacent to the Cemetery, and across the Baltimore Pike to East Cemetery Hill, were two-fold. First, he desired to preserve key areas of the battlefield from any future development. Second, he wanted to increase the acreage of Evergreen’s holdings, and set a portion of this newly acquired ground aside for the interment of at least some of the battle dead.

As early as June 1862, McConaughy had advocated in Gettysburg’s Adams Sentinel that within Evergreen there should be “an eligible site and commodious ground” for the resting place of local soldiers who had died in the war. McConaughy suggested that the new burial ground should feature a “handsome and imposing shaft of marble, around which shall be interred the remains … of all the glorious dead, native to, or citizens of our County, who died in the defense of the nation in this momentous struggle.” He concluded, “Let each grave be indicated by a small headstone,” and added, “the monument should be inscribed the names alike of privates and officers, without any other distinction whatever, save the simple yet eloquent record of the names and battlefields of our martyred dead.”

The proposed “Cemetery at Gettysburg,” Nurse Emily Bliss Souder predicted, would be “the most honorable burying-place a soldier can have. Like Mount Vernon, it will be a pilgrimage place for the nation.”

Several weeks of infighting between Wills and McConaughy followed, with each bombarding Gov. Curtin with letters and telegrams denouncing the other. Finally, for the sum of $2,475.87, McConaughy agreed to release 12 acres of West Cemetery Hill adjacent to Evergreen to be used by the states to inter the dead that still lay in makeshift graves. This land, Wills assured Curtin, was fitting as it had been the place where the Union forces had “dealt out death and destruction to the Rebel Army.” Emily Bliss Souder, a volunteer nurse from Philadelphia who counseled families not to remove the bodies of their loved ones, was cheered by the news. The proposed “Cemetery at Gettysburg,” she predicted, would be “the most honorable burying-place a soldier can have. Like Mount Vernon, it will be a pilgrimage place for the nation.”

After consultation with William Saunders, the Scottish-born architect selected to design the burial ground, Wills acquired five more acres to better accommodate his concept which, by chance or design, generally followed the plan proposed by McConaughy a year earlier: A central spot for the erection of a marble monument, with the graves of the fallen radiating from it in a semi-circle of granite slabs. The graves would be separated into sections arranged by the state that had enlisted them, but would be otherwise interred without distinction between privates and officers. Christened The Soldiers’ National Cemetery, it would be the first to group graves of officers and enlisted men side-by-side. As Drew Gilpin Faust noted in her 2009 book, This Republic of Suffering, the design, “like Lincoln’s speech” that later consecrated it, “affirmed that every dead soldier mattered equally regardless of rank or station.” Saunders’ plan also featured the planting of trees and shrubbery along the perimeter to provide shelter for visitors and enhance the solemn effect.

The ground was now ready to begin receiving remains of the fallen defenders of the Union battle line.

Charles T. Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Related story: A Place of Pilgrimage for the Nation: A photographic tour through Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.