By Charles T. Joyce

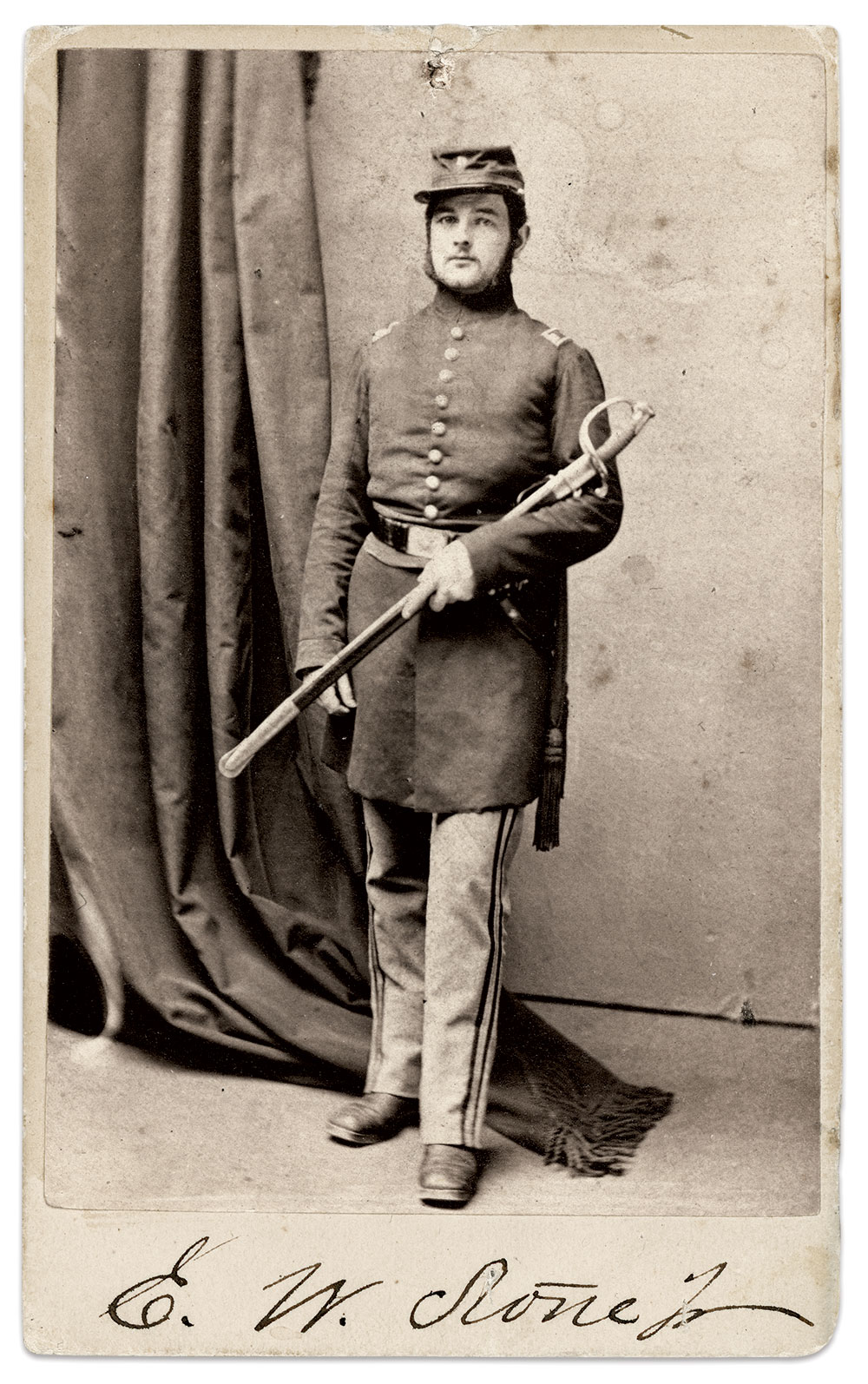

Immediately after issuing a congratulatory message to his victorious army on Independence Day 1863, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade sent a circular to his corps commanders, instructing them to detail burial parties to inter the thousands of dead who lay among their lines upon the battlefield. The following day, scores of Union officers were detailed to supervise men in this disagreeable duty. One of the officers is pictured here: Capt. Ebenezer Whitten Stone of the 1st Massachusetts Infantry.

A fellow officer in the 12th New Jersey Infantry also tasked with this assignment confided in his diary on Sunday, July 5, “all were ordered out to bury the dead.” He continued: “The ground here is very hard, full of rocks and stones, the digging is very laborious work, the dead are many, the time is short, so they got but very shallow graves, in fact the most of them were buried in trenches, dug not over 18 inches deep, and as near where they fell as possible, so as not to carry them far… . One man … died with his arm in such a position that it stuck up when put in the hole; a man took his shovel [and] struck it a blow breaking his arm so that it fell.” The officer explained that this was done “to save having so much dirt to throw.”

Soldiers engaged in these duties used whatever they had on hand—waste wood from used ammunition crates, leather flaps from discarded cartridge boxes, and the like—to fashion crude headboards to identify fallen comrades.

Torrential rains drenched Gettysburg in the days immediately following the battle, and water quickly filled many of the shallow burial trenches. One witness recalled that it was “necessary to lay heavy boards over the bodies to keep them down and in place.” The rainstorms had other undesirable effects; they washed the loose soil off of some of the bodies, such that “arms and legs and sometimes heads protrude” and wild hogs “were actually rooting out the bodies and devouring them.”

Future battlefield historian Bachelder, who had arrived soon after the fighting to, in his words, sketch “drawings of its various phases for historical pictures” that he planned to create and market to the citizenry of loyal states, reported to Pennsylvania Gov. Andrew Curtin that inscriptions on the temporary grave markers were largely “written with lead pencil and by the rains beating the fresh earth upon them they have already become nearly effaced.” He warned that the writing on many of the headboards would disappear before autumn.

Curtin faced a tough re-election campaign and knew he had to do something to meet the growing calamity of post-battle Gettysburg. After a visit on July 10, he tapped local attorney David Wills as his official agent. Aided by a state statute that had fortuitously been passed the previous year, Wills advised families of Pennsylvania’s slain that they could have their loved ones exhumed, coffined and sent home, with an attendant to accompany the body, all at the Commonwealth’s expense.

Volunteer nurse Emily Bliss Souder wrote to her brother that a “perpetual procession of coffins is constantly passing to and fro, and so it has been ever since we have been here; strangers looking for their dead on every farm and under every tree.”

By late July, however, a combination of factors rendered this plan unworkable. To be sure, embalmers and undertakers quickly arrived and did a brisk business, recovering and sending home the bodies of some 700 Union dead from the various states. Volunteer nurse Emily Bliss Souder wrote to her brother that a “perpetual procession of coffins is constantly passing to and fro, and so it has been ever since we have been here; strangers looking for their dead on every farm and under every tree.”

Still, there were simply too many graves, hastily dug and haphazardly marked, to be attended to in this manner before the elements took their toll. To make matters worse, fear of pestilence and disease from corpses exposed to heat and humidity resulted in a halt to soldier disinterment by friends and family, at least until cooler weather returned in the fall.

This unprecedented ecological and moral crisis demanded an innovative solution. A harried Wills wrote to Curtin on July 24, “humanity calls on us to take measures to remedy this … by making provision for the honorable burial of the dead of our state who may fall on the field.”

Charles T. Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Related story: A Place of Pilgrimage for the Nation: A photographic tour through Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““Humanity Calls On Us” : Pressing Problem With the Initial Burials at Gettysburg”

Comments are closed.