By Charles T. Joyce

David Wills orchestrated the logistics of disinterment and reburial. He solicited bids for the former and received 34 responses, choosing the low bid of $1.59 per body submitted by Frederick Biesecker. He, in turn, subcontracted the work to Basil Biggs, who received $1.25 of the number, according to a National Park Service publication.

Biggs, an African American born in Maryland around 1819, had moved to Adams County a few years before the war. His life before then is shrouded in mystery. There is strong evidence that his mother was enslaved, and that Basil’s father was her enslaver. She died when Basil was a child, and for the next dozen or so years he was forced to work in Baltimore as a teamster—possibly because he could not be considered free until he reached a certain age. Biggs then married, and by 1860 had a family of five. He moved them to Pennsylvania in large part because the commonwealth offered free education to Blacks, and Basil—himself illiterate—wanted a better life for his children. Despite Biggs’ educational limitations, when he arrived in Adams County he soon became known as a skilled veterinarian, and was called “Doc Biggs” by some of the locals. He is also widely believed to have been a conductor on the Underground Railroad, which thrived in this part of South Central Pennsylvania.

When the Confederates invaded, Biggs shuttled his family east to Columbia on the Susquehanna River’s far shore. He returned to Gettysburg alone. With the word that Gen. Robert E. Lee’s men were capturing Black people, whether free born or not, and sending them in shackles to Virginia, Biggs remained in town until June 26, when rebel soldiers first entered town on their way east to attempt the capture of Harrisburg. Then he borrowed a horse and galloped away on the York Road to join his family. When Biggs returned, the farm he had rented was ruined, with a large number of Confederate graves dotting the acreage. Just about all that he had left of any substantial material value were two horses and a large wagon. He used these assets to his financial betterment when he began work for the Cemetery.

To superintend Biggs’ efforts, Wills contracted Samuel Weaver. In May 1852, Weaver became Gettysburg’s first permanent photographer. According to an advertisement placed in the Adams Sentinel, he was “prepared, at all times, and in all weather, to take Daguerreotypes.” Weaver enjoyed a monopoly until 1859, when the Tyson brothers arrived from Philadelphia. Weaver promptly retired and gave his business to his son, Peter, who by 1861 had relocated the studio to nearby Hanover.

Weaver remained physically present whenever a federal corpse was unearthed, and sifted through the remains with an iron hook for clues to the soldier’s identity. Mass burials in trenches proved challenging in the search for evidence.

On Oct. 27, 1863, the project began. Biggs and Weaver worked as a team. A crew of about 8 or 10 individuals of color assisted Biggs in the disinterments. Weaver remained physically present whenever a federal corpse was unearthed, and sifted through the remains with an iron hook for clues to the soldier’s identity. Mass burials in trenches proved challenging in the search for evidence. The loss of hastily scribbled inscriptions on the makeshift grave markers due to the elements further complicated the identification process.

Weaver’s careful scrutiny decreased the number of unknowns. Wills reported that due to Weaver’s “untiring and faithful efforts, the bodies in many unmarked graves have been identified in various ways. Sometimes by letters, by papers, receipts, certificates, diaries, memorandum books, photographs, marks on the clothing, belts, or cartridge boxes, &c., have the names of the soldiers been discovered.”

Weaver’s record of these poignant recoveries was published by the Pennsylvania Legislature. This “List of Articles” is revealing: Of the 278 soldiers discovered with personal items they had carried into battle, nearly ten percent had “ambrotypes.” Examples include “a mother and two daughters,” or “a young lady,” or a “female” with them in their final moments. Others had “likenesses” in their possession—presumably cartes de visite. These numbers are impressive considering most fighting men kept their more personal possessions in knapsacks, which were usually laid aside and left behind when the fighting started. Nevertheless it seems many soldiers wanted images of those that mattered most to them in their possession when in combat.

The disinterred remains were placed in wood coffins and transported to the Cemetery. A local boy, Leander Warren, shared these duties with Biggs’ men, as his father, David Warren, had a separate contract to haul bodies for 20 cents each. Leander remembered that Biggs “had a colored boy hauling with a team of two horses and he could haul nine coffins a trip. I hauled only six.” Young Warren also recalled that “while the work of uncovering the dead on the field was done by Negroes, the reburial at the national plot was in charge of white men.” Some 30 or 40 of these workers—all white—were employed.

Whether Biggs felt slighted by this apparent form of racial segregation is unknown. From the monies he received for his work, Biggs purchased a farm of his own in April 1865. His land embraced the Copse of Trees that came to be known as the Confederacy’s High Water Mark.

Weaver expressed pride in his work and his further efforts to document the Cemetery in photographs. A week after Lincoln dedicated the grounds in November, Weaver wrote to his brother William that he had spent the momentous day assisting his son Peter in “getting a Negative of the large assembly on the Semetary [sic] ground, which I think is very fine.” He continued, “as soon as all the dead soldiers are buried in the National Semetary, to take a Picture of the whole ground & also take a Negative of the ground for each state.” He concluded with enthusiasm, “it is going to make one of pertiest Semetary in [the] U.S.”

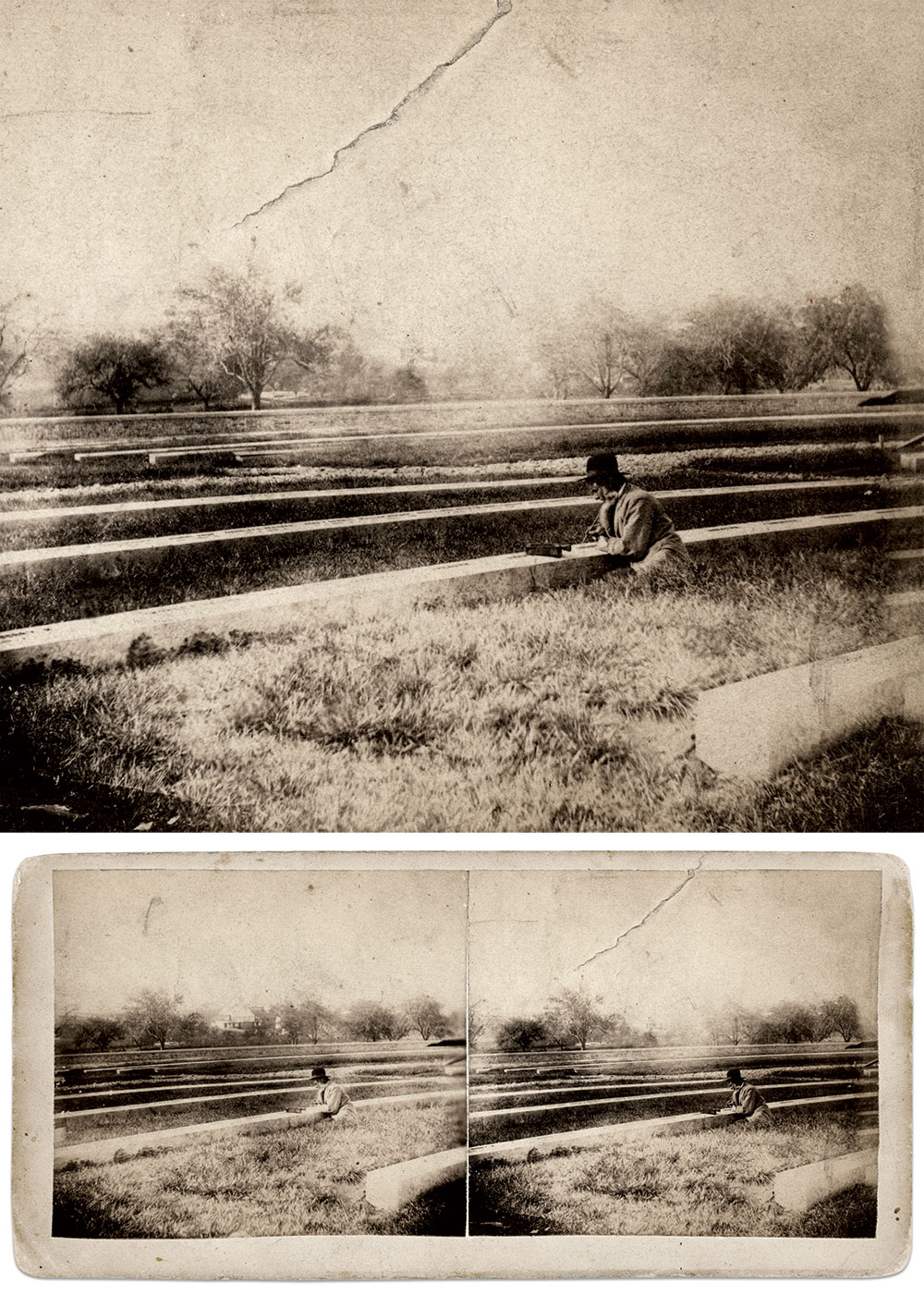

There is no evidence that Weaver completed the series of Cemetery photographs he had scoped out in November 1863. A tragic railway accident cut his life short in 1871. However, in the summer of 1866, Weaver asked his nephew, Hanson (who had briefly joined with Weaver’s son in the family photography business) to take a series of stereo views of the Cemetery. At least two of these images, meant to be family mementos and not intended for public consumption, featured Weaver himself. One of them is pictured here.

Charles T. Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Related story: A Place of Pilgrimage for the Nation: A photographic tour through Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “A Retired Photographer and Free Man of Color Join Forces to Disinter the Dead at Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery”

Comments are closed.