By Charles T. Joyce, with images and artifacts from the author’s collection

A decade after the guns fell silent at Gettysburg, the battlefield’s first comprehensive tourist guide appeared in print: Gettysburg: What to See, and How to See It. Its author, John Badger Bachelder, had emerged as the leading historian of the battle. His interpretation included the Copse of Trees, the scrub oaks that became a focal point of Pickett’s Charge, as the High Water Mark of the Civil War. One might have expected Bachelder to give this spot his highest recommendation to tourists.

But he didn’t.

“If the visitor to Gettysburg has but one hour at his command,” Bachelder wrote, he should go not to the Copse of Trees, but another locale a half mile northeast. “Cemetery Hill,” he assured readers, would “unquestionably be the place to spend” that precious hour.

A 21st century visitor similarly short on time would likely not receive similar advice. A 2013 issue of Gettysburg Magazine with the provocative title, “If I Had One Last Day to Spend At Gettysburg,” makes no mention at all of Cemetery Hill, or of the National Cemetery that crowns it. This modern slight is not surprising. Nestled by large ornamental shrubbery planted after the battle, the Soldiers’ National Cemetery today feels removed from the fields of long ago strife that surround it. A place of manicured quietude and reflection, it is difficult to conceive of this ground as the key point in the Union line of battle. But it was this, and it remains far more.

Beyond being the location of the most transformative speech in American history, the land features the final resting place of over 3,500 men and boys who fought and died in the three days’ combat, and for decades after the war, functioned as a gathering place for their comrades who survived. What follows is a photographic tour of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, using period images drawn from photographs and artifacts in my collection.

Bisected by the Baltimore Pike, Cemetery Hill is actually composed of three discernible components. East of the Pike, the Hill descends sharply from its peak elevation of 100 feet. On the evening of July 2, this area was the scene of desperate combat, one of the few spots during the fighting where the struggle raged hand-to-hand. Across the Pike and to the south lies the Evergreen Cemetery, created just a few years before the battle in the bucolic fashion of the mid- 19th century, a place for townsfolk to enjoy a contemplative stroll. Also across the Pike is the western summit of the Hill, a little less than 20 acres of high ground which in 1863 sloped gradually down to the Taneytown Road and a wide open plain south of the town.

This land is the subject of our tour.

Related stories:

- The Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg Is Conceived

- “Humanity Calls On Us” : Pressing Problem With the Initial Burials at Gettysburg

- A Retired Photographer and Free Man of Color Join Forces to Disinter the Dead at Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery

West Cemetery Hill: “A remarkable position”

Before it was consecrated by a “few appropriate remarks” of President Abraham Lincoln, western Cemetery Hill in the Summer of 1863 was simply a few plots of open farmland, graced by a small apple orchard and a field of corn. But from the moment the armies clashed here on July 1, its military value became manifest. Selected as a rallying point for routed Union forces, the Hill was quickly converted into a stronghold dominated by scores of Union cannon.

Historian Allen C. Guelzo suggests that the Hill was possibly the region’s singular place to anchor a defensive line in the face of an advancing army. “Gettysburg,” he notes, “lies on a vast plain which stretches eastward from South Mountain and the Appalachian chain to the Susquehanna River which undulates in waves of north-south ridge lines.” These ridges “made reasonably good postings for infantry, but their crests lack the elevation required for nineteenth century artillery … Likewise, their spines are usually too narrow to support batteries of artillery with any ease, since artillery (unlike infantry) used a substantial backspace to accommodate limber chests, caissons, horse teams, and battery wagons.” The “principal exception to this geography monotony,” he notes, “is Cemetery Hill.”

A broad flat plateau, West Cemetery Hill “constituted an artillerists’ dream come true.”

A broad flat plateau, West Cemetery Hill “constituted an artillerists’ dream come true: a gun platform with plenty of room to accommodate at least 18 field pieces, plus their teams and chests.” Furthermore, according to a period artillery manual, the Hill’s elevation was the ideal height to “allow either an unobstructed arc to rifled guns firing shell to the north or west” or to blast case shot or canister straight upon oncoming attackers moving toward it from southwest.

Whether or not this position was geographically ordained to be the locus of the federal battle line, Union gunners were keenly aware of their good fortune; by the afternoon of July 2, some 43 field pieces were crowded on or around its western crest. The overall commander of these massed batteries reported that while this concentration of federal firepower “made the best target for artillery practice the enemy had during the war,” there “was another side to it.” He explained that “we commanded their guns as well as they did ours. In addition to this we commanded the plain perfectly, with no timber intervening, over which the enemy’s infantry must advance to the charge.” The first stop on our tour is the location of one of these artillery units: Battery H, 1st U.S. Artillery.

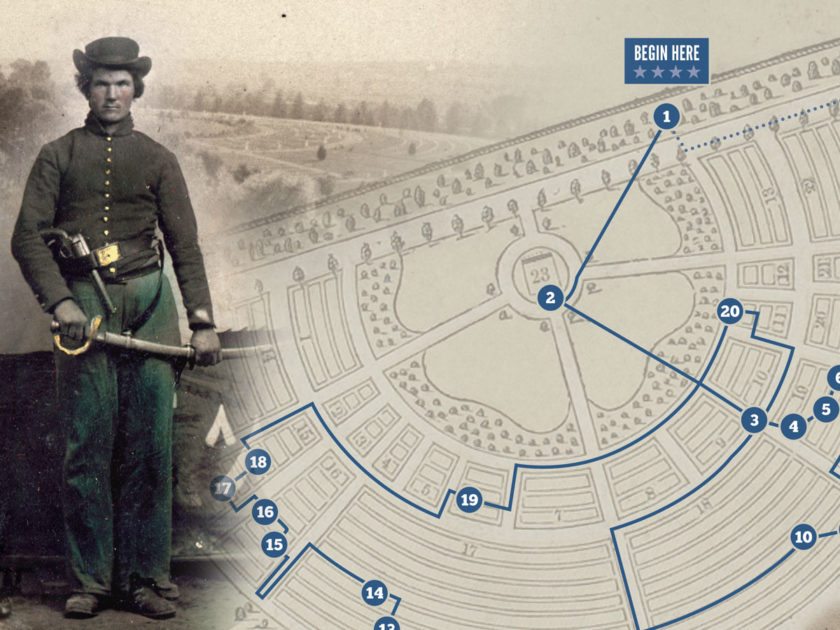

Begin at the Taneytown Road entrance to the Cemetery. Walk past the rostrum on your left and the Lincoln Speech Memorial on your right. Follow the path past monuments to several Union batteries on the right until reaching a pair of 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannon.

Download a printable version of this tour (PDF).

STOP 1: Position of Battery H, 1st U.S. Artillery

Led by 1st Lt. Chandler Eakin, the Battery’s six 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbores moved into position on the afternoon of July 2 and dueled with enemy guns while enduring the pesky musketry of Confederate snipers at the edge of town. The Battery had been in action for less than an hour when Eakin suffered a nasty wound and was carried from the field. Command devolved to 2nd Lt. Philip D. Mason.

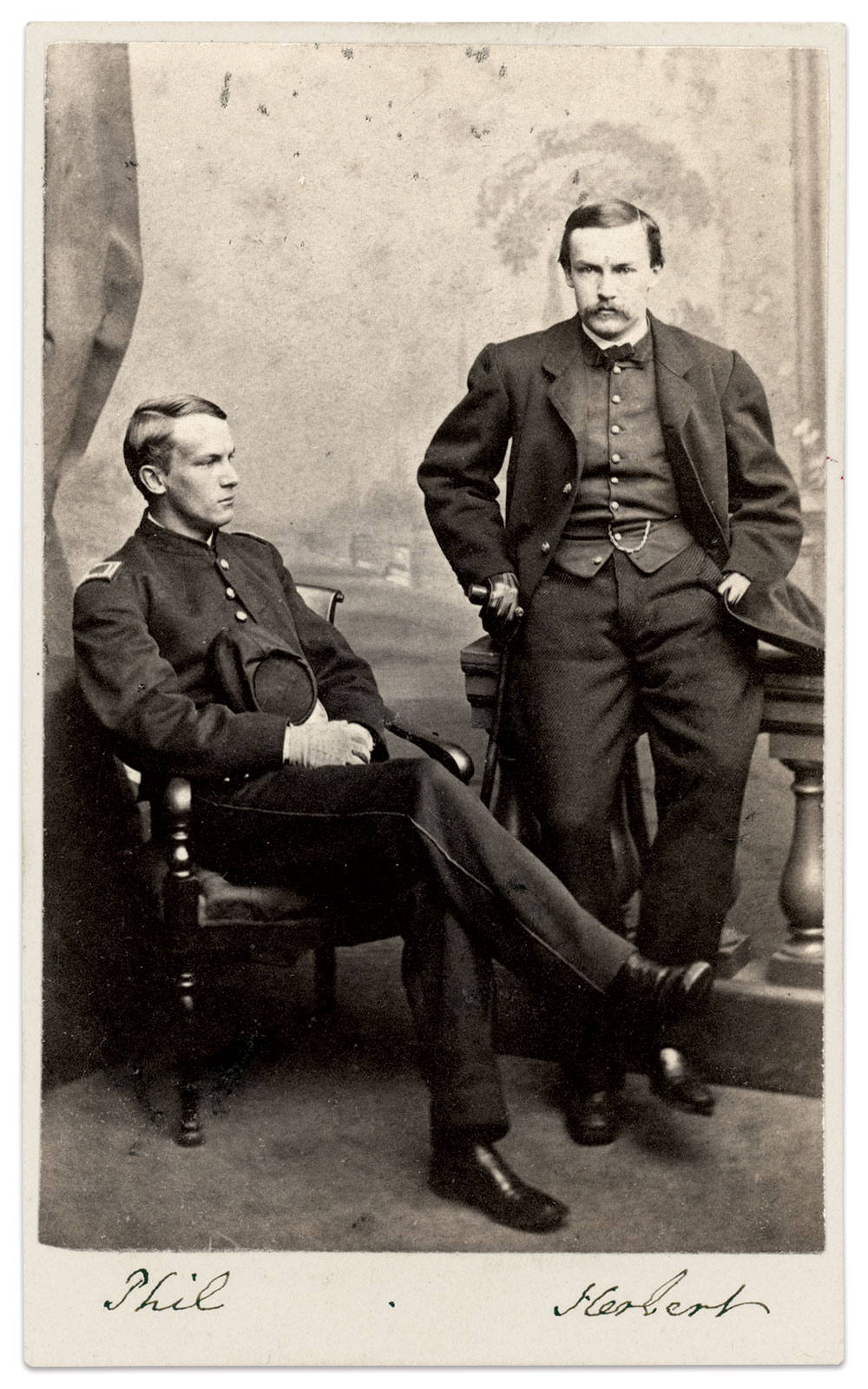

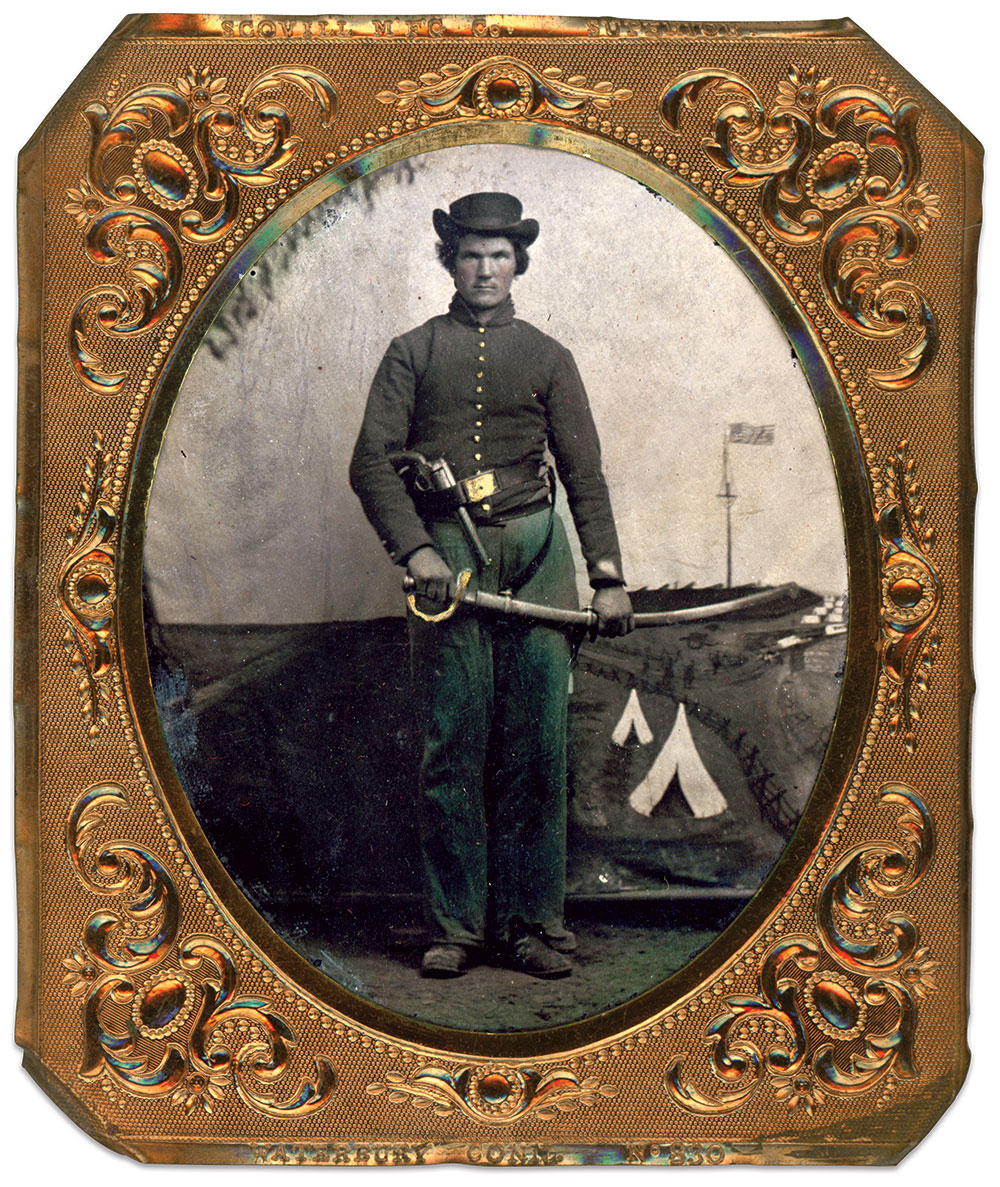

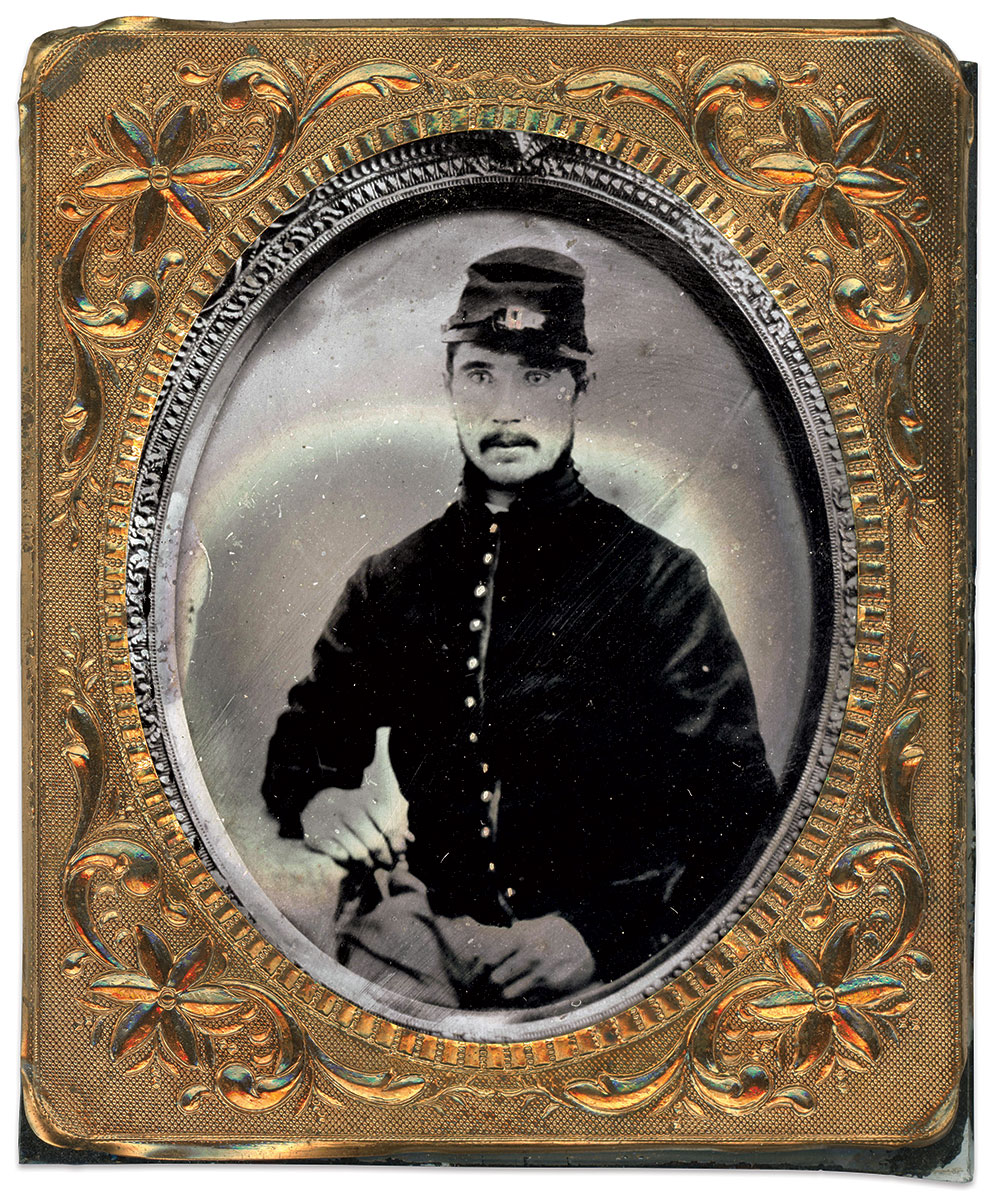

Mason hailed from one of the most wealthy and socially prominent families in Boston; his grandfather a former U.S. Senator, his father a renowned art collector. When war arrived both Philip and his younger brother Herbert enlisted, the latter earning a captaincy in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, widely known as the “Harvard Regiment.”

Under Philip’s direction, Battery H continued its counter battery fire on July 3, until Longstreet’s assault began over the open fields to the southwest. Then, recalled Philip’s temporary field commander, Maj. Thomas Osborn, the guns of Battery H and the other massed artillery units on West Cemetery Hill fired into the charging rebel columns, “and the havoc produced upon their ranks was truly inspiring.”

Waiting for the rebels was his brother Herbert and the rest of the 20th, stationed behind a stone wall just over 2,000 yards southwest from Philip’s battery. Battery H’s guns and other Union cannon smashed into the left half of the rebel attack before it even made it halfway to Herbert’s men, and funneled others toward their position near the Copse of Trees. The artillery was finally forced to cease fire when the remaining Confederates pushed across the Emmitsburg Road and out of view of Philip’s cannoneers on West Cemetery Hill.

Now it was his brother’s turn to meet the foe. Herbert later recorded in his diary that Longstreet “attacked us in force with his infantry, nearly succeeding in breaking our line. Our regiment having got into confusion while changing front to prevent the enemy from making a flank movement, I was shot in the groin while trying to rally toward the colors.” The wound shattered Herbert’s hip bone, causing his left leg to be two-and-a-half inches shorter than his right when it healed.

The injury ended his military career. Discharged for disability in March 1864, he returned to Boston. At some point that spring he made his way assisted by a cane into the studio of Black & Case for a portrait with his brother.

Just a few months later, at the Battle of Trevilian Station, a cannon shot tore off Philip’s right leg and the greater part of his right hand. He lingered until July 18, 1864, before dying of his injuries. Philip’s obituary mourned him: In “the long list of young men who have nobly given their lives for their country, there has been no one more devoted to the national cause, no one who has evinced a braver spirit, or met wounds and death with more calmness and heroism than this accomplished officer.”

Herbert lived in pain for the next 20 years before committing suicide at his family’s summer home in 1884. “Men died by the thousands at Gettysburg, and thousands more were crippled there,” observed a local newspaper. “Captain Mason lived for 21 years after the battle, but there is reason for believing that his early death is traceable in some degree to the costly service he tendered his country there.” Today, Herbert and Philip Mason rest side by side in the family plot in Cambridge, both ultimate casualties of the Civil War.

From the Position of Battery H, cross the path and walk to:

STOP 2: The Soldiers’ National Monument

Standing at the monument’s front, the semi-circular arrangement radiates down a gentle slope into inner and outer rings separated into sections of states. Each ring is composed of multiple rows of graves. On period maps, each row is lettered in descending order from the monument, with the furthermost row being “A.” In the Cemetery’s records, each grave in a row is numbered; from the front of the Monument, the rightmost grave is designated as “1” and then proceeds numerically to the left.

On July 4, 1865, workers installed the cornerstone for the monument rising from the Cemetery’s epicenter. It was finished in 1869. The 60-foot-tall, Rhode Island granite memorial is topped by a marble statue of the “Genius of Victory” and flanked by sculptures representing War, History, Peace and Plenty. The Soldiers’ National Monument became a focal point of countless cartes de visite, stereo and cabinet cards, and postcards through the years.

It is time now to meet a few of the men and boys whose mortal remains rest here.

Start with your back to the figure on the base of the Soldiers’ National Monument of the seated female writing with stylus and tablet. This is the muse of History, listening to the soldier beside her, War, telling the story of the battle and the names of the honored dead for her to record. Move straight down the slope past the Connecticut Section in the inner ring to the Massachusetts Section, composed of 159 bodies, located in the outer ring.

It is appropriate that our photographic survey of the graves begins here; even before the concept of a national cemetery had been conceived, agents dispatched by the Bay State proclaimed that the battlefield was the most suitable spot to inter the dead. They also insisted the layout be grouped by state.

Proceed down the first row of graves and to the far right to the first plot in the row:

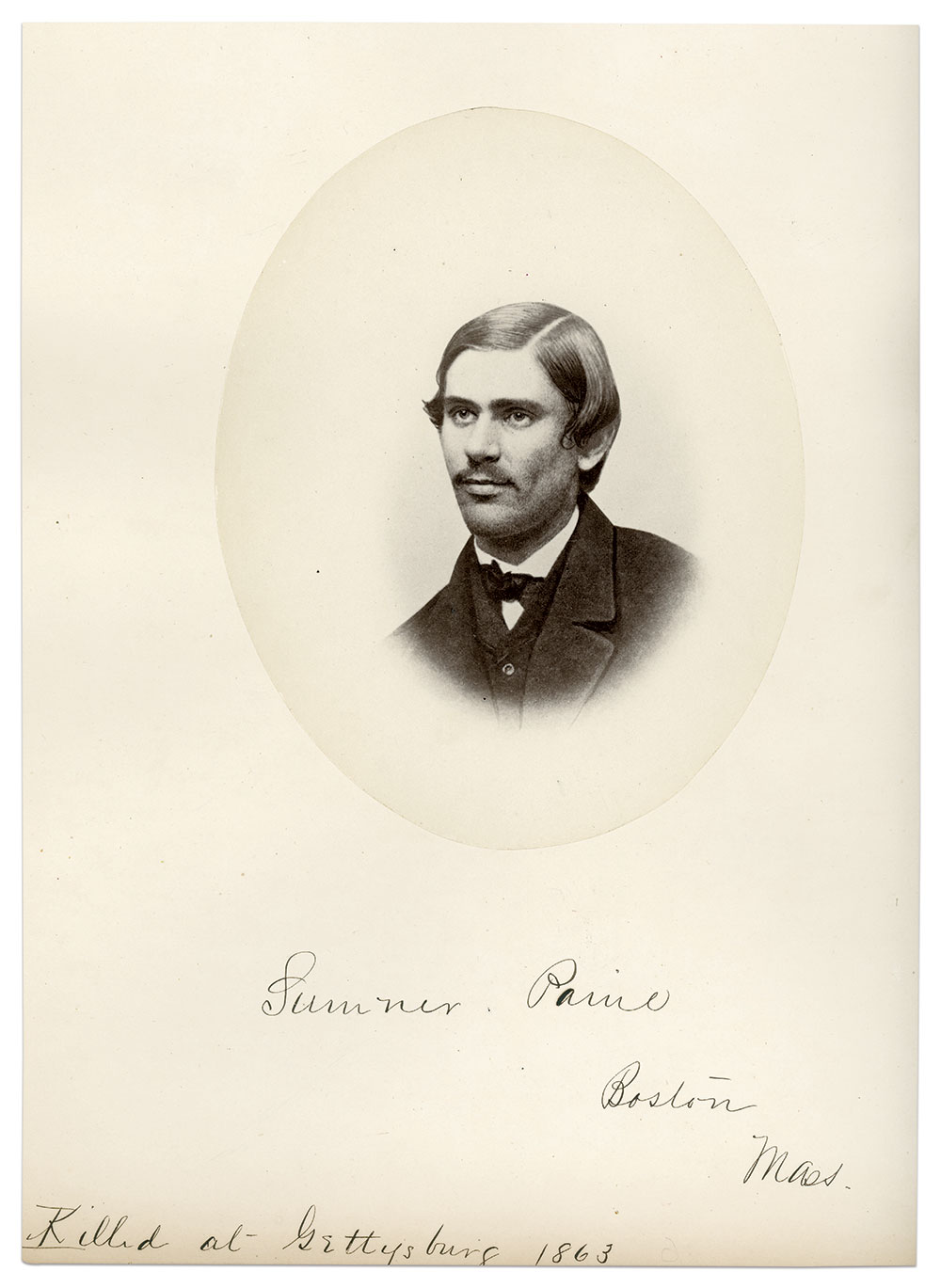

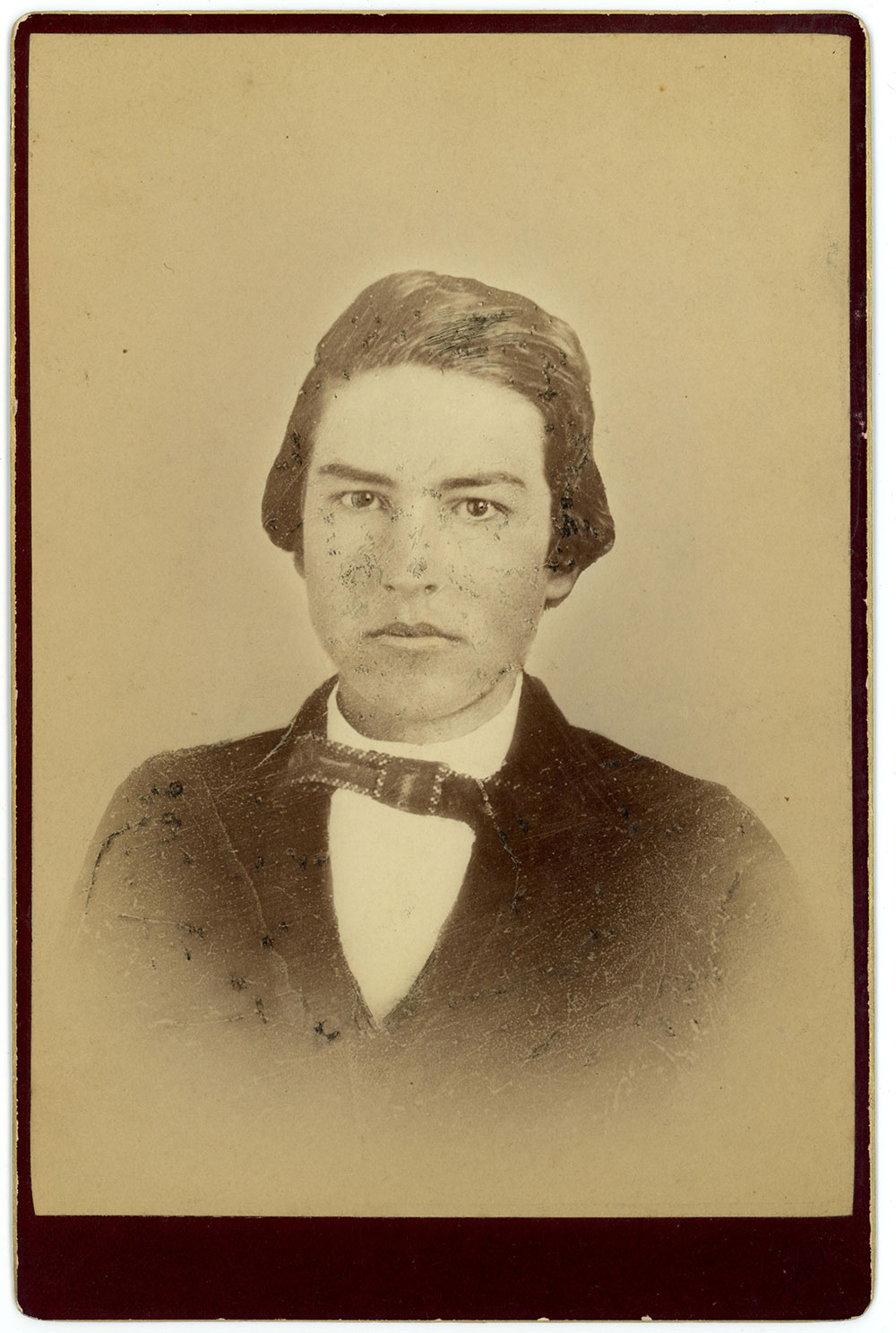

STOP 3: 2nd Lt. Sumner Paine, 20th Massachusetts Infantry (Plot E-1)

This grave represents Massachusetts’ commitment to lay their fallen heroes to rest at a public spot in Gettysburg rather than private burials at home. Had young Sumner (he had only turned 18 in May) been killed or mortally wounded, his well-heeled Boston family had the means and motivation to recover him.

The great-grandson of Robert Treat Paine, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the brilliant but reckless Sumner had been expelled twice from Harvard. He had a desire to experience combat. After the Battle of Chancellorsville, he wrote his parents that he “wanted to see some good, tough fighting and try a few bayonet charges.”

This attitude, coupled with his youth and a heavy hand when it came to disciplining the men in his company, prompted 210 enlisted men to sign a petition of protest to Gov. John Andrew in June. The document described Sumner’s penchant for sadistically suspending soldiers from trees, tying them in stocks or elevating them on “instruments of torture.”

It is unlikely that Gov. Andrew would have acted on this missive. In any event, the battle intervened. On July 3, as the regiment moved forward to confront Pickett’s Charge, Sumner urged his men on, screaming, “Isn’t this Glorious!” before a shell burst tore through his ankle, almost severing it from his leg. Paine raised himself on an elbow, and waved his sword with the other hand, yelling “Forward, forward!” until a hail of bullets riddled his arm and chest, killing him. As modern chroniclers of the 20th Massachusetts Edwin R. Root and Jeffrey D. Stocker put it, Paine’s “naive desire to ‘see some good, tough fighting’ had indeed been realized,” and he rests today in this plot, where he will “remain forever eighteen years old.”

Move down the slope one row and to the left approximately 10 plots until you come to:

STOP 4: George L. Boss, 15th Massachusetts Infantry (Plot D-10)

Boss, 19, lived with his parents and younger siblings in Fitchburg when he enlisted in the 15th Massachusetts Infantry in July 1861. During the brutal march north to Gettysburg, Boss fell out of the ranks, but rejoined his regiment by the late afternoon of July 2, when the 15th was thrown forward to the Emmitsburg Road as part of a forlorn hope to stop the Rebel advance. During the short but sharp combat, Boss received an ugly wound to his hip from a shell that may have been fired by a Union battery blasting away at the Confederates from Cemetery Hill.

Taken from the field to the Jacob Schwartz farm, which served as the field hospital for his division, he awaited treatment. Overwhelmed surgical staff could not keep up with the influx of wounded. A comrade remembered that early on the morning of Independence Day, Boss had yet to received medical attention. He wrapped himself in a blanket and crawled over to a campfire for warmth and quietly passed away.

Boss’s parents erected a cenotaph in his honor in the family plot at Fitchburg’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. It reads: “Killed in Battle, Buried at Gettysburg.”

Move down the slope to the next row, and over to the left approximately 13 plots to:

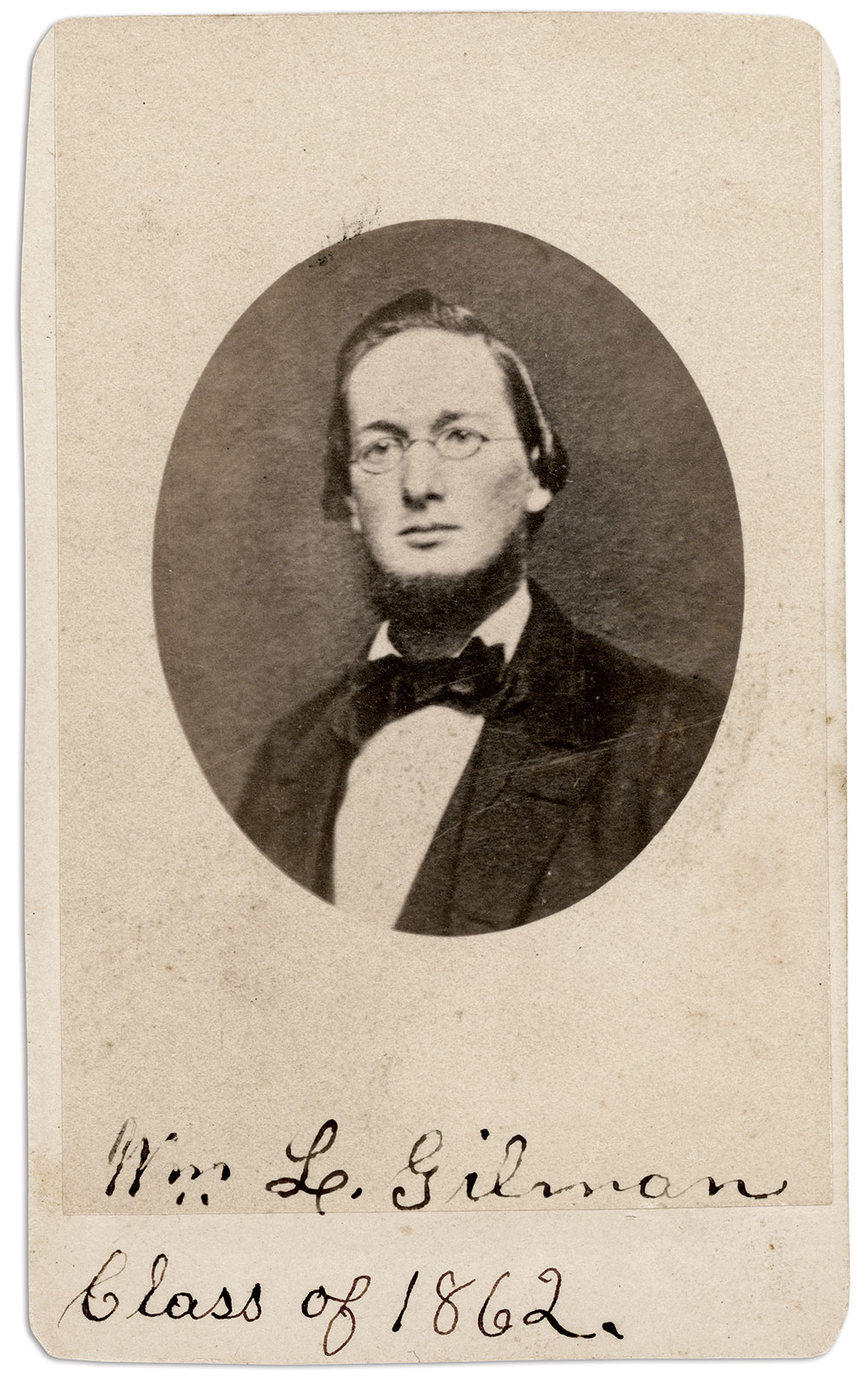

STOP 5: Corp. William L. Gilman, 32nd Massachusetts Infantry (Plot C-23)

Born about 1834 in Greene County, N.Y., Gilman studied for the ministry at the newly formed Theological School of St. Lawrence University in Canton. One of his fellow students, Olympia Brown, became the first woman in America to receive ordination with full denominational authority. Gilman graduated in the class of 1862 and began his vocation in Newton, Mass.

In August, 1862, he enlisted as a corporal in the 32nd Massachusetts Infantry. As befitting his occupation (listed on the muster rolls as a clergyman) Gilman was detailed to serve as a nurse in December and served in this capacity until February 1863, when he returned to the ranks. Months later on July 2 at Gettysburg. Gilman and the 32nd faced fierce combat at Stony Hill and in The Wheatfield. In that action, the former cleric suffered a severe gunshot wound to his left knee, necessitating amputation at the 5th Corps field hospital.

The Chaplain of the 60th New York Infantry visited the hospital and found Gilman. He reported that the ball that pierced Gilman’s leg and traveled upward in a trajectory that would have entered his abdomen had it not been “arrested in its progress by a copy of the New Testament” in Gilman’s blouse pocket. The Chaplain added that the bullet came to rest at the first book of Timothy, verse 15, that read, “this is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation; that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am chief.”

Later, another minister found Gilman in a barn with over a hundred wounded men, “doing all in his power to make all around him resigned,” bestowing a “patient, hopeful, cheerful word for everyone who moaned in pain or grief,” and “by his cheerful and Christian talk, putting a strong and happy heart into every one of them.” Tragically, however, Gilman suffered a fatal secondary hemorrhage. Before he died, he confessed that he “would like to recover; but, if death ensues, I do not regret the sacrifice I make to crush out this rebellion.” He passed away on July 30, proclaiming his peace at “leaving this world for a new and wider field of labor.”

Remain on this row and move to the left 9 plots to:

STOP 6: Jeremiah Young Wells, 19th Massachusetts Infantry (Plot C-32)

Wells, a 34 year-old teamster living in Lynn, kissed his wife Frances and 7 year-old daughter Florence goodbye and enlisted in the 19th Massachusetts Infantry in December 1861. He was present for duty with the exception of being hospitalized from September 1862 to the spring of 1863.

At Gettysburg, Wells suffered wounds in the foot and leg during the second or third day of fighting. Surgeons performed an amputation and Wells did not survive it. Reports conflict on his death date: July 13 or 21. Initially buried at the divisional field hospital on Jacob Swartz’s property, his remains were later disinterred.

Move down to the next row, and to the right about 19 plots to:

STOP 7: William Marshall, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry (Plot B-16)

Early on the morning of July 3, William Marshall and the men of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry looked upon an open meadow at the base of Culp’s Hill. They glimpsed an enemy force of unknown strength at the far edge. An order was issued to advance pickets and “feel” the enemy position. But by the time the directive reached the 2nd and another regiment, the 27th Indiana Infantry, it had been garbled into a demand that the two units launch a full-scale assault.

Marshall’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Charles R. Mudge, muttered that the order was “murder,” but it was nonetheless an order. Mudge led his men in a dash across the field, where he and 44 other officers and men were killed or mortally wounded. Among those was Marshall, a blue-eyed, dark-haired 32-year-old mechanic from Boston. He left behind a wife, Delia, and a teenaged daughter and two young boys. Delia never remarried, and died in 1898. Marshall, a private during his enlistment, is listed as a corporal on his grave marker—possibly a clerical or stone-cutters error.

Facing away from the Soldiers’ Monument, proceed directly to the right into the Pennsylvania Section. Starting on the outermost line of graves (Row A), move right approximately 46 plots to:

STOP 8: Frederick Gilhousen, 148th Pennsylvania Infantry (Plot A-23)

In August 1862, wagons filled with new volunteers trundled out of the small town of Brookville in Jefferson County, Pa. Though they “went off with cheers and shouts,” the historian of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry noted, they left “behind them a sense of loss and loneliness” amongst the townsfolk who had come to see them off.

The oldest recruit in the wagon train, 41-year-old Frederick Gilhousen, left the care and maintenance of his family farm to his wife Lavinia and their four small children.

Less than a year later at Gettysburg, Gilhousen and his comrades passed the evening of July 1 in “sober reflection” on what the morrow might bring. The adjutant recalled that Gilhousen, “in particular, felt strongly impressed that this battle would end his days.”

The next day, Gilhousen and his company advanced into The Wheatfield with 57 men and came out with 20. Gilhousen numbered among the wounded, shot in the left thigh by a minie ball. While the wound was not believed mortal, his presentiment of death “so preyed upon him,” wrote the adjutant, “as to destroy his courage and in a few days justify his forebodings and cause the loss of a good soldier.” He died at the Second Corps Hospital on July 16.

An obituary in the Brookville Republican entitled “Soldier Gone” noted that Gilhousen left behind “a wife and family to mourn the loss of a kind husband and father.”

Move one row up toward the Soldiers’ Monument, about face away from it and proceed approximately 14 plots to the left, to:

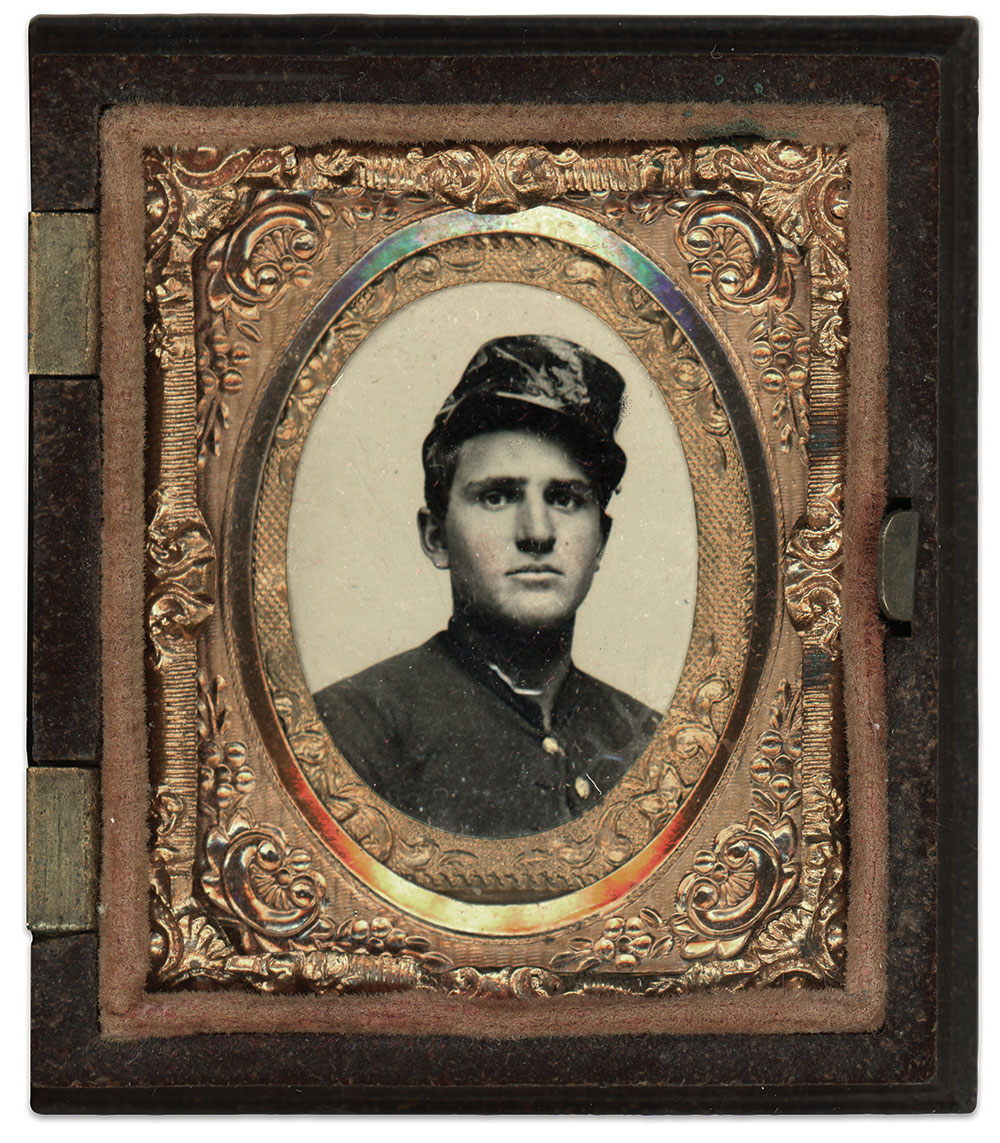

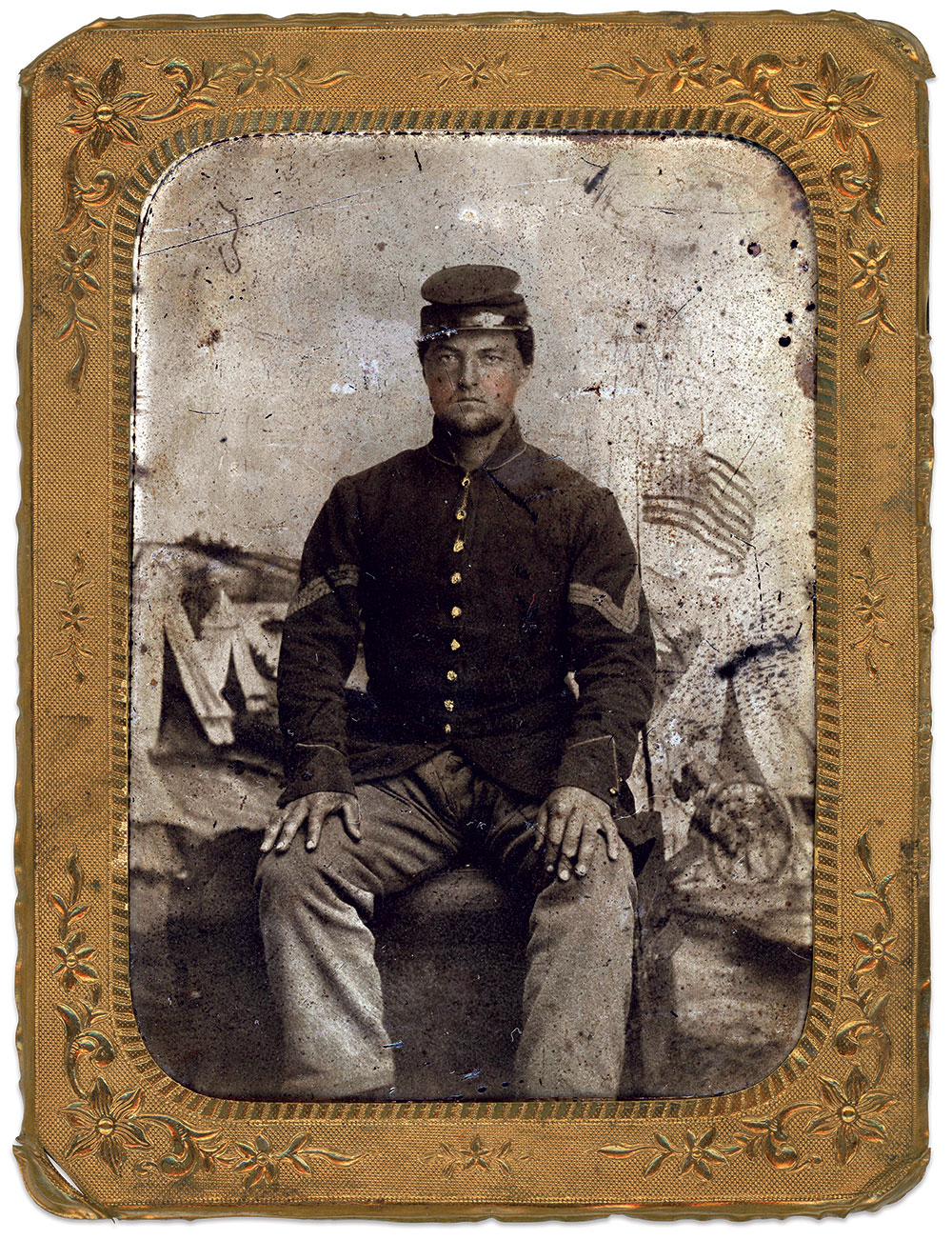

STOP 9: Solomon Shirk, 107th Pennsylvania Infantry (Plot B-65)

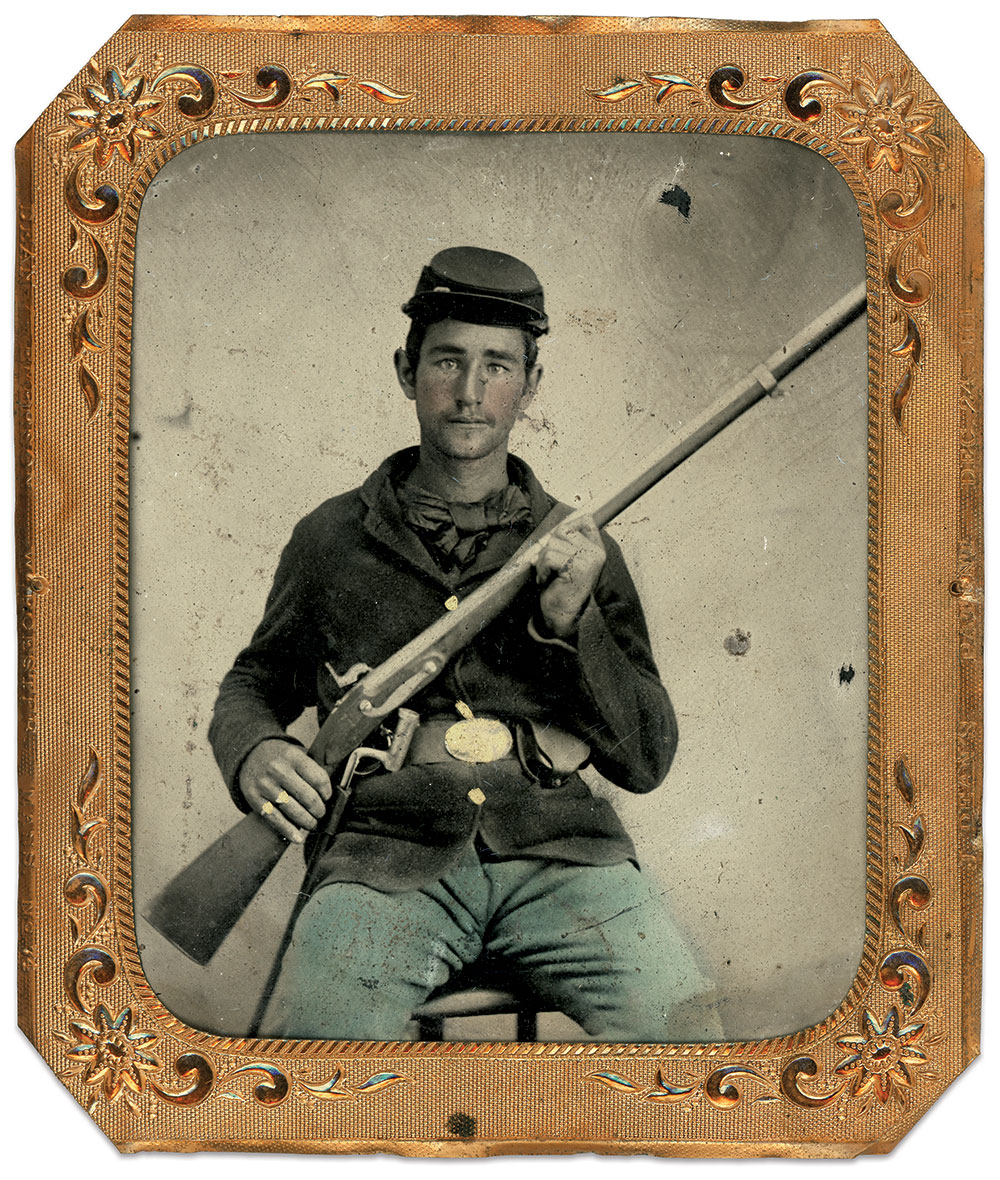

Shirk enlisted in the 107th in January 1862. Underaged, he may have grown the wispy mustache shown in this portrait to make himself appear older. His older brother, David, enlisted with him.

In the fighting at Oak Ridge on July 1, both brothers suffered wounds. David’s injury was minor, but Solomon was hit in the abdomen and died a painful death at the 2nd Division, 1st Corps Hospital on July 3 or 4. David recovered his dead brother’s wallet and brought it home.

Move two rows up and to the right approximately 18 plots to:

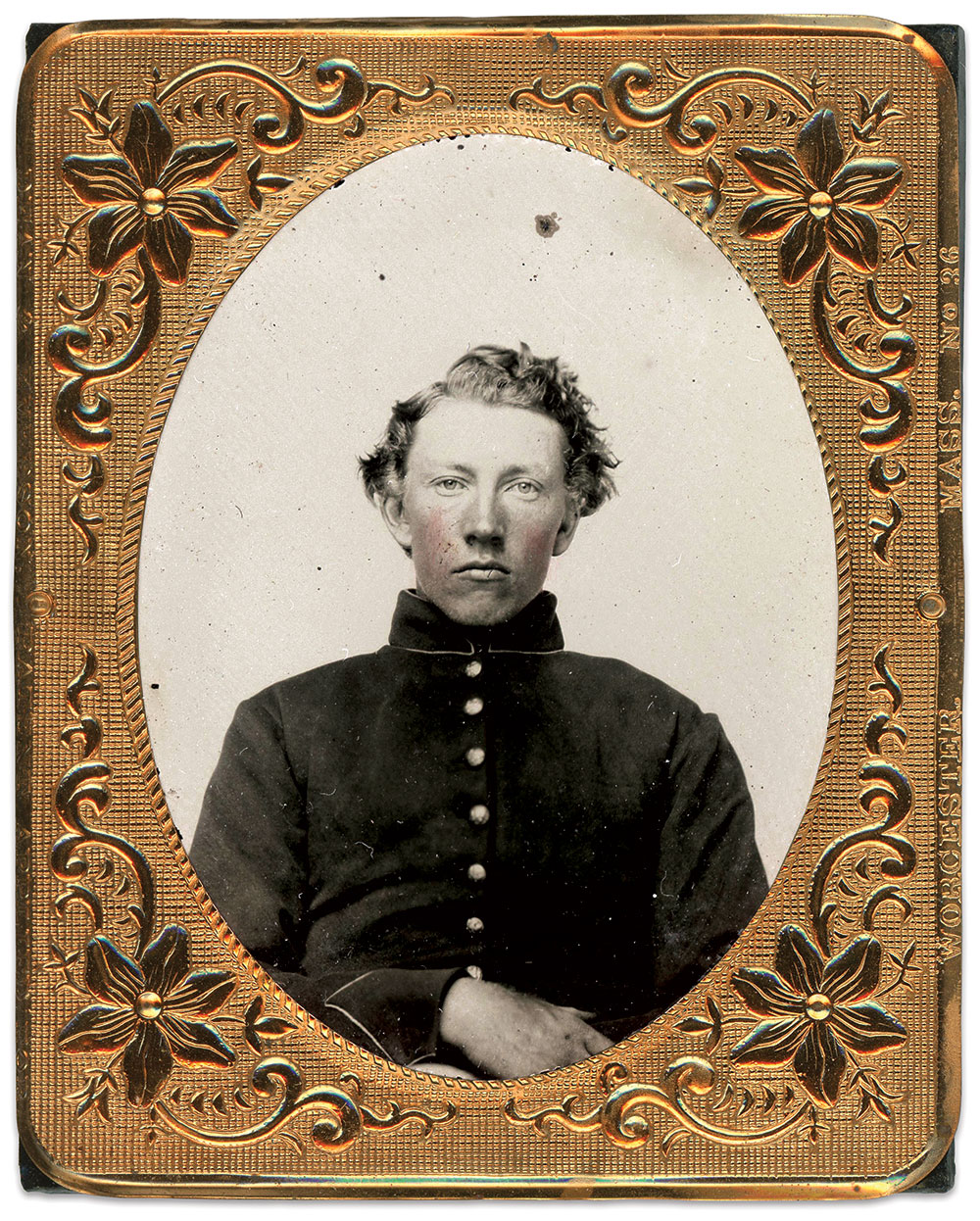

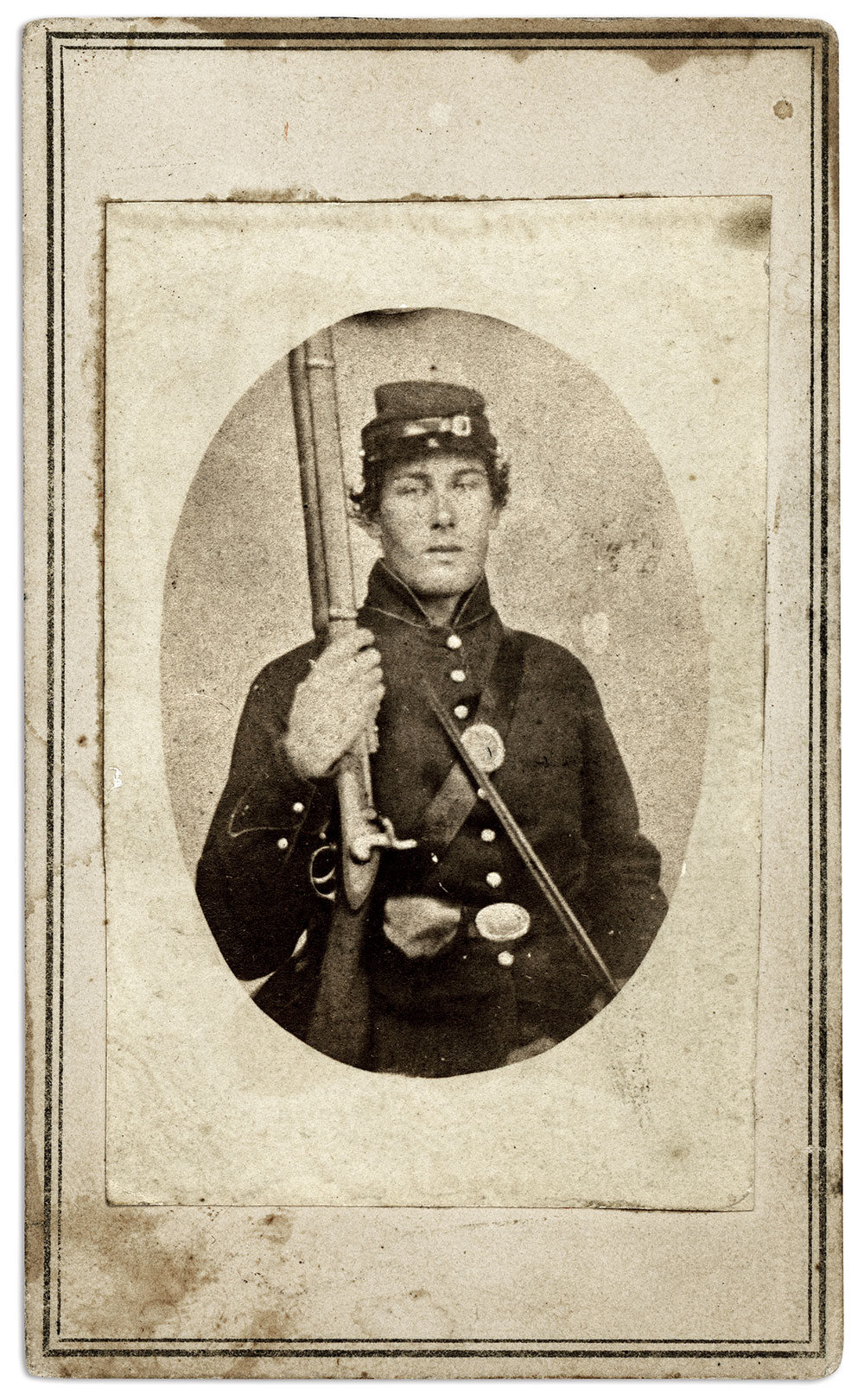

STOP 10: William H. Dunn, 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry (Plot D-76)

Will Dunn, a 19-year-old with blue eyes, red hair and freckles, was the eldest boy of 11 children of Arthur and Eliza Dunn. Father Arthur eked out a living as a huckster (a peddler of fruit and vegetables) in Pittsburgh, Pa., aided by Will before his first-born joined the 62nd in July 1861.

By 1863, Dunn had seen a fair share of fighting and was “as tired of soldiering as any person.” But he wrote that he would never “play sick to get my discharge,” adding “I think an honorable discharge is better to me than a fortune,” signing off, “I remain your red-headed, affectionate son until death.”

Death came instantly on a skirmish line in The Wheatfield on July 2 after a bullet struck him in the head. A sergeant wrote to Dunn’s father on July 24 with an assurance that “the grave of your brave son … is marked so that you will have no trouble in finding his last resting place.” The July 27 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer published a notice from a pair of embalmers noting Dunn’s grave on a “Partial List of Killed at Gettysburg,” and promised to direct relatives to the spot. Dunn’s family elected to have their boy buried with his fellow soldiers.

Still facing away from the Soldiers’ Monument, move to the right into the New York Section and back to Row A, and move approximately 59 plots to the right to:

STOP 11: 2nd Lt. Charles A. Foss, 72nd New York Infantry (Plot A-25)

Charles Augustus Foss, 22, began his military service in June 1861 as a corporal in the 72nd. By the end of the year, he had been promoted to first sergeant of his company. Foss served in this capacity over the next two years, during which the regiment suffered losses in the Peninsula Campaign and Battle of Fredericksburg. In the fighting at Chancellorsville, Foss received a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant of Company C.

At Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 2, Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade unleashed a powerful assault that severely disrupted Union lines. The Confederate attack scattered the units to the left of Foss’s men back, exposing the flank of the 72nd and forcing the regiment to withdraw in confusion to Cemetery Ridge. Once order was restored, the federals rallied and counterattacked.

At some point in the action, Foss received a severe wound in the leg. Surgeons at the 3rd Corps Field Hospital performed an amputation. Foss succumbed to its effects on July 7. Comrades buried his remains in a field of clover at the hospital before they were disinterred and reburied in the Cemetery.

Remaining on Row A, continue to the right 28 plots to:

STOP 12: Chester Smith, 44th New York Infantry (Plot A-53)

A Quaker from North Collins, N.Y., Smith enlisted in the 44th New York Infantry in September 1862. The six-footer had just turned 20 when he and his comrades fought at Little Round Top.

Two days later, on Independence Day, fellow soldier Erastus L. Harris wrote to Smith’s mother, Rachel, with the sad news that her son had perished in combat that claimed 20 of the 40 men in Company A. “If I could say one word that would comfort you in this hour of your bereavement most gladly would I do it,” stated Harris. “If to know that your son was never influenced by the vices and evil influences of the camp and that he was cool and brave in battle and did his whole duty will be any consolation to your stricken heart, then can I comfort you with at least that assurance?”

Harris also proclaimed that Chester “fell defending the cause of freedom and he sleeps on a soil unpolluted by the footsteps of a slave,” and went on to assure the grieving Rachel that, while he had been unable to bury her son in a separate grave, Chester was interred by “the pioneers of the Regt. with the rest of our Company that fell,” and that his grave was “numbered so that it can be found at any time.”

Rachel wrote Harris back, and enclosed paper and a postpaid envelope to continue their correspondence. Though her letter is lost, Harris’ response on August 10 indicates she wanted more details. Harris explained that Chester was buried in a trench “in the rear of the rocky hill where we were engaged.” Rachel’s husband, William, had also apparently asked about his son’s wound. Harris reported that it occurred “soon after the battle commenced,” and “ the ball struck somewhere in the thigh passing up into his vitals.”

Harris asked the grieving parents what they thought “of the proposition you may have noticed in the papers to bury all these dead heroes on Cemetery Hill together and have a suitable monument to commemorate their noble deeds?” Harris reasoned, “if I had fallen on that glorious field I should be content to sleep my last sleep with my brave comrades.”

Rachel and William Smith agreed, and made no attempt to recover Chester’s remains. They did, however, erect a cenotaph behind the Quaker Meeting House in North Collins. It reads: “Chester, Son of William and Rachel Smith, died in the Battle of Gettysburg, Pa., July 2, 1863, Age 20 Yrs. and 27 Days.”

Turn about to face the Soldiers’ Monument, move up to two rows and turn to the left approximately 13 plots to:

STOP 13: 2nd Lt. Franklin K. Garland, 61st New York Infantry (Plot C-35)

When the war came, Franklin “Frank” Kellogg Garland worked as a blacksmith and lived with his parents, Erasmus and Martha, and sister Mary in Sherburne, N.Y. He enlisted as first sergeant in Company A of the 61st New York Infantry in October 1861. By 1863 he had risen to second lieutenant. He served at this rank during the fighting in The Wheatfield until a bullet tore through his left lung.

Carried to a temporary field hospital on the Taneytown Road, stretcher bearers placed Garland aside a fellow wounded officer of the regiment, Charles A. Fuller of Company C. Fuller recalled that Garland was able to raise himself on his elbow, but his breathing was “very painful to hear,” because every time he drew a breath, air passed through the punctured lung “with a ghastly sound.”

Garland succumbed to his wound on July 4. His mother filed a pension claim with affidavits in support by townsmen. Another affidavit, sworn to by daughter Mary, disclosed that her father Erasmus was a drunkard who could not support his family. She noted that her late brother had habitually sent considerable sums of money home to help. The government approved the application, and the economic relief it provided enabled the family to erect a cenotaph in Garland’s memory in Sherburne’s Christ Church Cemetery.

Move up two rows, turn right approximately 13 plots to:

STOP 14: Frederick A. Archibald, 137th New York Infantry (Plot E-20)

Frederick A. Archibald , a 27-year-old farmer from Owego, N.Y., bade farewell to his wife Helen in 1862 and joined the 137th New York Infantry. Before dawn on July 3, 1863, he and his comrades occupied the far right flank of the Union line on the slopes of Culp’s Hill.

It was something of a miracle that Archibald was still alive. Less than 12 hours earlier, the regiment had been caught in a Rebel assault that hit them on their front, flank, and rear. Undaunted, the 137th pulled back into a traverse trench they had constructed, then launched two bayonet attacks that drove back the Southerners. The fighting ended about 10 p.m.

The next morning brought another Confederate assault. A wave of brown and butternut infantry swept toward them. An officer in the 137th noted, “for nearly six hours the rattle of musketry was incessant. Not for an instant did the firing cease.” In the end, the New Yorkers and the rest of the Yankee line held their ground.

The regiment paid a high price for its success. The long list of casualties included Archibald, killed sometime that morning. Buried on Henry Spangler’s farm on the Baltimore Pike, workers later disinterred and re-buried his remains in the Cemetery.

Helen applied for and received a widow’s pension. She never remarried, and died on July 6, 1914, almost 51 years to the day that she lost her husband. She is buried alone in a cemetery in Port Jervis, N.Y.

Move to the immediate right to the Michigan Section. Go down to Row A, then up to Row C, 11 plots to the right to:

STOP 15: Austin Whitmond, 1st Michigan Infantry (Plot C-12)

An historian of Union burials estimated that a quarter of the markers in the Cemetery have errors. This is the result of misread temporary markers, bookkeeping errors, or because the stonecutters were inattentive or not fully literate. The marker for Austin Whitmond of the 1st Michigan Infantry illustrates the problem. He is listed as Austin Whitman of the 5th Michigan Cavalry.

Whitmond, 24, perished on July 2 in the fighting on Stony Hill. His mother, Catherine, applied for and received a pension on his behalf.

Move up one row, and turn right approximately 10 plots to:

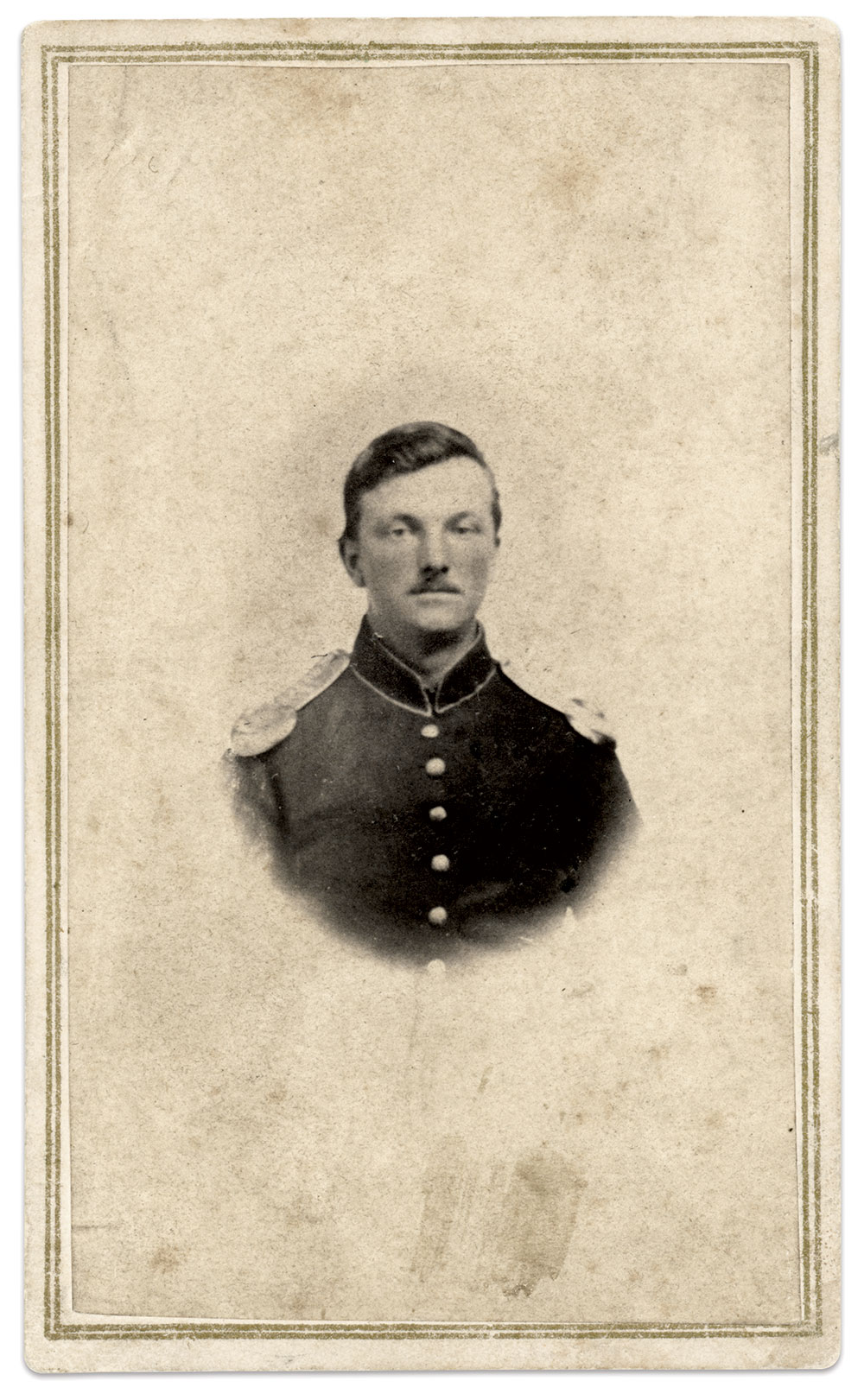

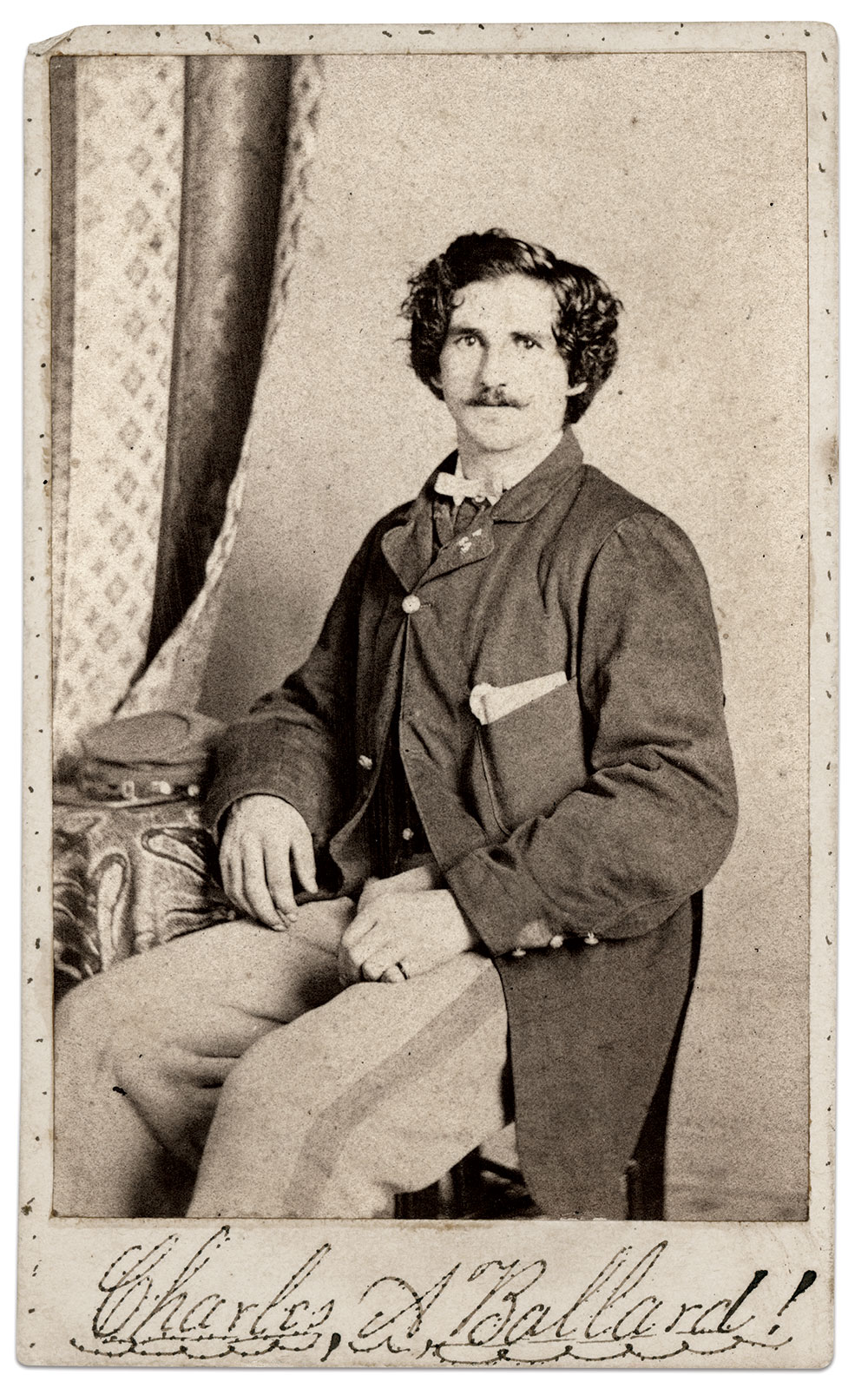

STOP 16: Sgt. Charles A. Ballard, 5th Michigan Cavalry (Plot D-2)

Nine graves in the Michigan Section are inscribed with names of men who are not buried there, and did not die at Gettysburg, leading one Licensed Battlefield Guide to describe it as “a researcher’s nightmare.”

This is one example. Charles Alfonso Ballard did serve as a sergeant in the 5th Michigan Cavalry, and he suffered a gunshot wound to his right forearm on July 3 as he and his fellow Wolverines grappled with JEB Stuart’s cavalry.

But he survived. Transferred on July 9 to Satterlee General Hospital, in what is now West Philadelphia, he remained there until discharged in the summer of 1864 to accept a commission as second lieutenant in the 127th U.S. Colored Infantry. At some point during his hospitalization he traveled east across the Schuylkill River to Heiss’ Gallery at 10th and Chestnut Street, and posed for this portrait. He died in 1929 at age 87 in Spanaway, Wash., where he had moved to get into the lumber business and real estate. His remains rest in a Spanaway cemetery.

There is no record of him ever visiting his Gettysburg grave marker. The identity of the individual who is buried there is unknown.

Proceed to the right to the Maine Section, down to Row C, and approximately 5 plots to the right to:

STOP 17: Sgt. Enoch C. Dow, 19th Maine Infantry (Plot C-12)

Peacetime mariner Enoch C. Dow lived with his parents, Orchard and Jane, and six siblings in the seacoast town of Belfast, Maine. On the one-year anniversary of the First Battle of Bull Run, he enlisted in the 19th Maine Infantry. He proved a good soldier, rising from the ranks to corporal and then, in March 1863, sergeant.

With his advancement came increased pay, which Dow mostly sent back to his father. He confessed, “If I keep it with me I shall loose [sic] it or fool it away.”

Before the Battle of Chancellorsville, he wrote to his older sister, Wealthy, that “the battle will be over and the victory decided by the time you receive this without doubt. There is many a poor fellow soldier that never will see the sun sink behind the horizon again. I may be one of that number. However, we will not think of that but trust to [a] greater power.”

At Gettysburg two months later, Dow and the 19th engaged in savage fighting on July 2, launching a counterattack that helped shore up the Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge at a critical moment. Dow suffered wounds in the hand, leg, and head during this combat and was taken from the field. His tentmate, Alfred Stinson, secured permission to search for his friend after the fighting ended in this sector. “I found him,” Stinson later recalled, “just as he was breathing his last. After he passed away, with the help of another comrade, I scooped out a shallow grave, rolled him in his blanket, buried him, marked his grave ‘Sergt. E.C. Dow,’ and left him in his glory.”

Back in Maine, Dow’s family erected a cenotaph at Narrows Cemetery in Sandy Point. It consists of a marble obelisk with a carving of the flag, and the words, “Member of Co. E, 19th Reg’t Maine Vol.s.” In 1913, Stinson visited Dow’s resting place in the Cemetery. As he was sitting there, where you are now, he wrote that his thoughts “drifted back to the night that I laid him away, and my tears ran like rain.”

Move up two rows to Row F, turn left approximately 1 plot to:

STOP 18: William H. Day, 17th Maine Infantry (Plot F-11)

In August 1862, 18-year-old William H. Day left the family farm in Brownfield, Maine, to join the army. He enlisted in the 17th Maine Infantry. As the only son and main support to his parents, Alvah and Eliza, he allotted 10 dollars of his monthly soldier’s pay to be sent home.

Less than a year later at Gettysburg, on July 2, a gunshot fractured Day’s left shoulder as his regiment struggled with a Georgia brigade for control of a stone wall bordering The Wheatfield. Treated at the 3rd Corps Field Hospital and moved to Camp Letterman, he died on the last day of August. His father, who had been in poor health for many years, predeceased him by a week, passing away on August 22. William’s mother applied for and received a pension, which she collected until she died in 1889.

Move up to the outermost row of inner ring of graves. Facing the Soldiers’ Monument, go five sections over to the New Hampshire Section, and move up to Row B, to:

STOP 19: Unknown Soldier, 2nd New Hampshire Infantry

Of the 3,512 soldiers buried in the Cemetery, over 2,600 were listed as unknown. Many of the unknowns have partial identifications thanks to the efforts of Samuel Weaver to search the remains for clues. He determined the body buried in this plot served in the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry. The regiment fought in the Peach Orchard. The soldier in this grave was initially buried behind the Wentz farmhouse on the Emmitsburg Road. During the disinterment, Weaver noted that the corpse’s face sported “red chin whiskers.”

Licensed Battlefield Guide Emeritus Roy Frampton deduced that only one of 11 men of the 2nd whose bodies were never identified could be buried here. He may be William C. Drummer of Keene, N.H. During the battle, William received a wound in the leg and in the confusion of fighting was left on the field where he apparently bled to death. His family erected a cenotaph for him in Woodland Cemetery in Keene. It reads in part “died at Gettysburg, Body not found.”

Face about to the Soldiers’ Monument, and proceed to the right five sections to the Minnesota Section, to:

STOP 20: Memorial Vase to the dead of the 1st Minnesota Infantry

In October 1867, two decades before monuments to individual regiments began to populate the battlefield, veterans of the 1st Minnesota Infantry visited the Cemetery and placed a marble funeral vase where their comrades lay buried. As the guru of Gettysburg battlefield photography, William Frassanito, observed, this urn “will forever hold the distinction of being the very first battle-related monument ever erected anywhere on the field at Gettysburg.” At the time, Harper’s Weekly reported that the Minnesotans established a fund, the interest of which to be “used by a lady of Gettysburg in keeping bright and fresh the red, white and blue flowers which bloom in the vase.” The reporter observed that the crimson verbena leaves that fell on the white marble of the urn’s base “remind us of the red tide that stained this field.”

A year later, on May 30, 1868, the practice of strewing the graves in the Cemetery with fresh flowers on Decoration Day commenced.

As the late historian James Weeks argued in his 2009 book, Gettysburg: Memory, Market, and an American Shrine, the town’s economic interests in promoting the battlefield for pecuniary gain always contended with the desire to respectfully commemorate the fallen defenders of the Union. This competition grew in the late 1870s and 1880s, which featured both an expansion of the tourist trade and renewed interest of veterans to honor their comrades.

Nowhere was the tension between secular and sacred more pronounced than on Cemetery Hill. On its east side, and on land immediately to the south, an almost carnival-like atmosphere pervaded whenever the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) held encampments. At one such event, the G.A.R.’s weekly newspaper, the National Tribune, noted “lemonade venders, sideshow operators, and badge fiends” filled “every available spot along Baltimore Street,” and “even the monkey and fat woman show was at hand.” Yet, by crossing the street and escaping into the grounds of the Cemetery, the veteran and the tourist could return to a place where solemnity still reigned.

Return to the New York Section, Row C, approximately 15 plots to the right to:

STOP 21: James Gray and Edward Peto, Cowan’s Battery (Plots C-116, 117)

In July 1886, the survivors of Capt. Andrew Cowan’s 1st New York Independent Battery journeyed to Gettysburg to discuss plans to erect a monument by the Copse of Trees where they had fought on July 3. Cowan led the pilgrimage, accompanied by Horace Williams, an African American who had served as cook for the officers during the war.

On Independence Day, the group “resolved to go, in a body, to the National Cemetery, and hold a short service on the spot where their comrades are buried.” One of the veterans who chronicled the event noted, “In the Cemetery there are avenues of splendid trees … affording delightful shade. Here the soldiers lingered lovingly, for to them the spot is hallowed ground.”

Photographer Levi Mumper approached Cowan’s men and offered to take their picture. They agreed. All purchased a copy and Cowan ordered more to send home to the families of the dead.

“Such pictures have a value,” explained the veteran chronicler, “hard for those to realize who had no part in the battles of the war.”

The men paid tribute to the grave sites of three fallen comrades.

Henry Hitchcock (E-105), was hit in the thigh by a shell fragment on July 3 and died after 12 hours of suffering.

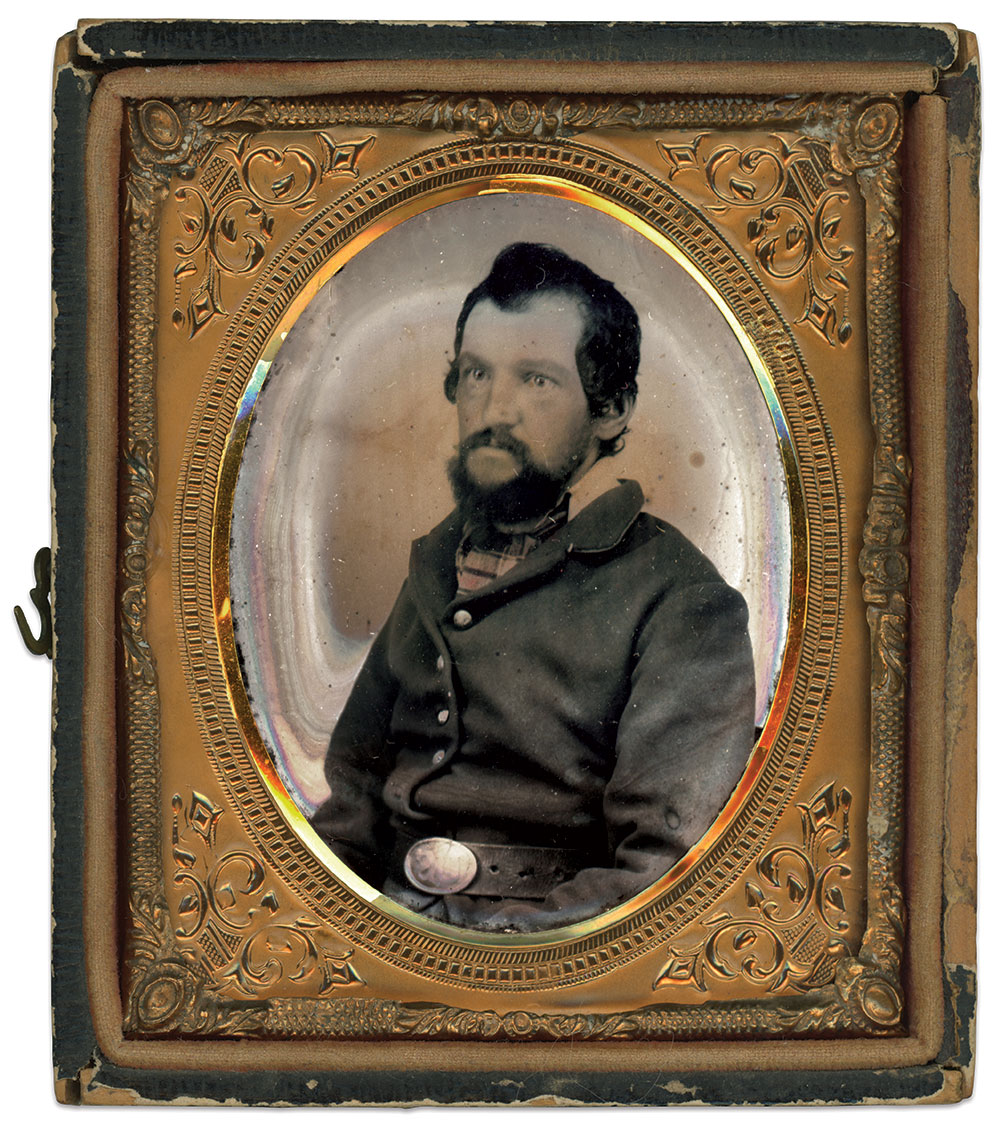

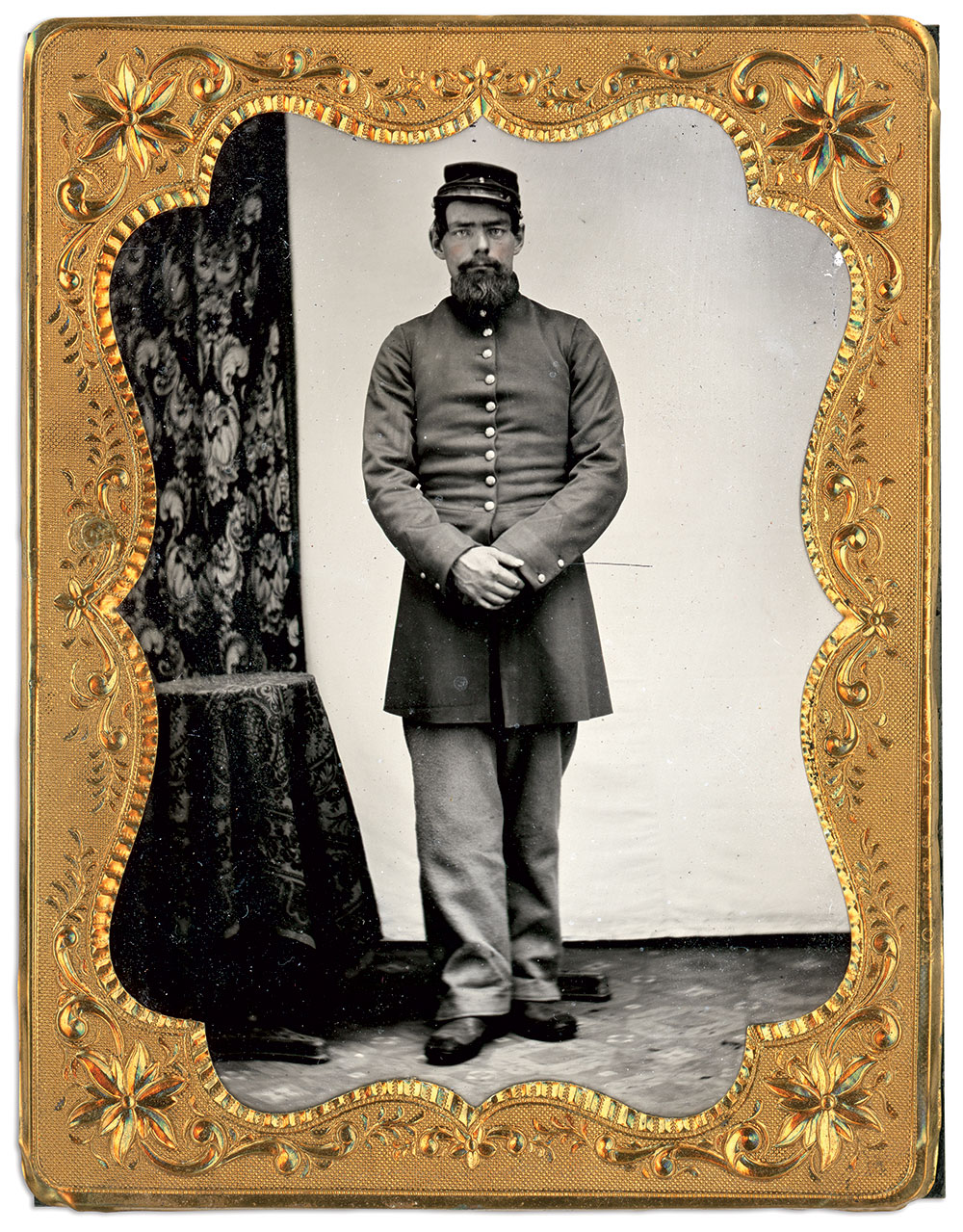

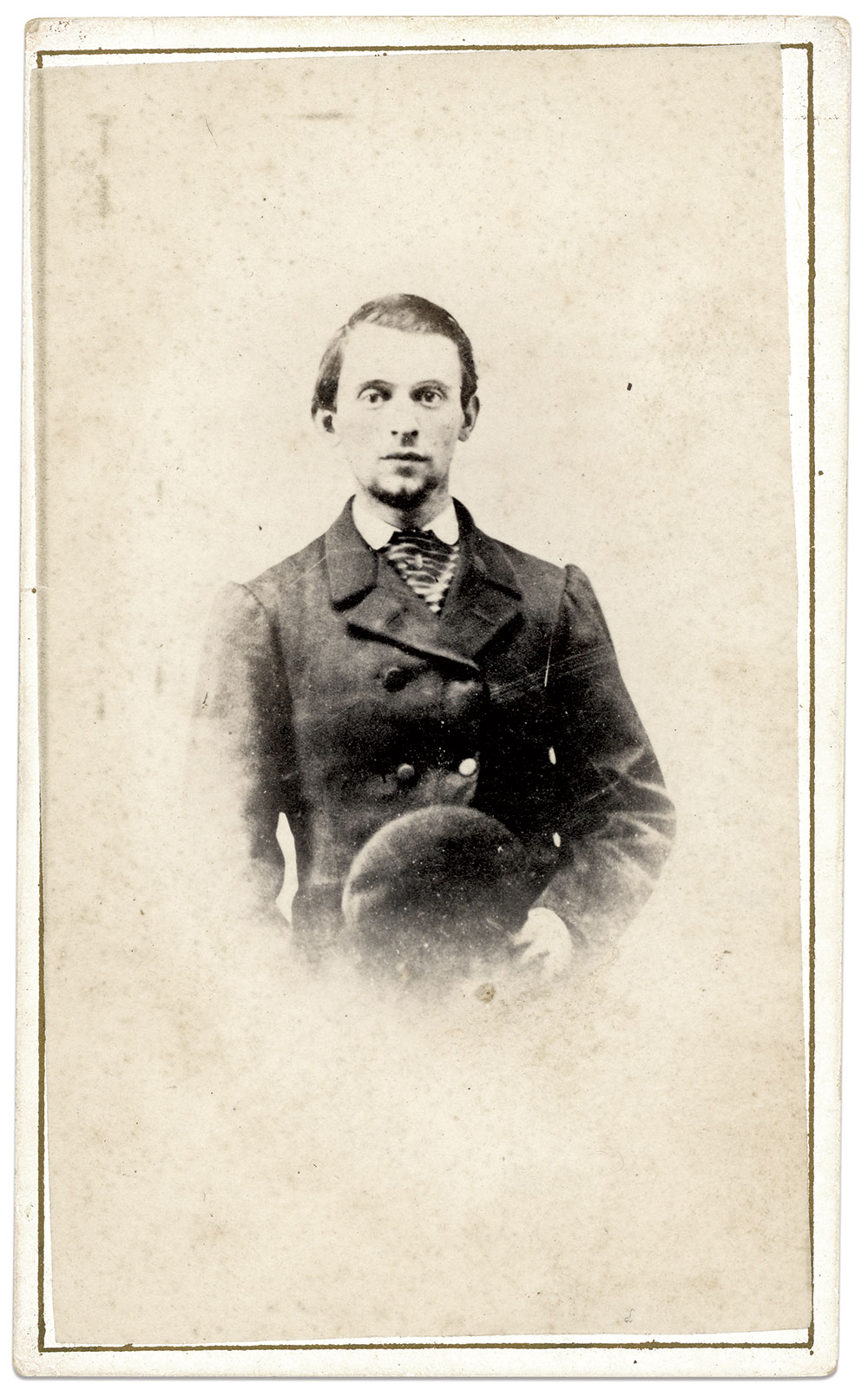

James Gray (C-116) and Edward Peto (C-117) were buried side-by-side, which seems fitting as evidence suggests they were friends before the war. Gray, an 18-year-old born in New York to Irish immigrants, and Peto, 28, who emigrated from Great Britain shortly before the beginning of the war, lived in Ledyard, N.Y., when they joined the army.

They died on July 3. Gray was killed instantly after a bullet struck him in his head. Peto also died quickly, but in a particularly gruesome fashion. Cowan reported that just as Pickett’s men had crossed the Emmitsburg Road on their final advance toward Cemetery Ridge, a cannon shot screamed into the Battery, hitting Peto in the abdomen and cutting him nearly in two at the hips.

In 1903, when Peto’s widow petitioned the government for a pension increase, Gray’s younger brother James wrote an affidavit on her behalf. In 2003, these portraits were found together in the effects of Lucy Mary Gray Bowness, Gray’s great-niece.

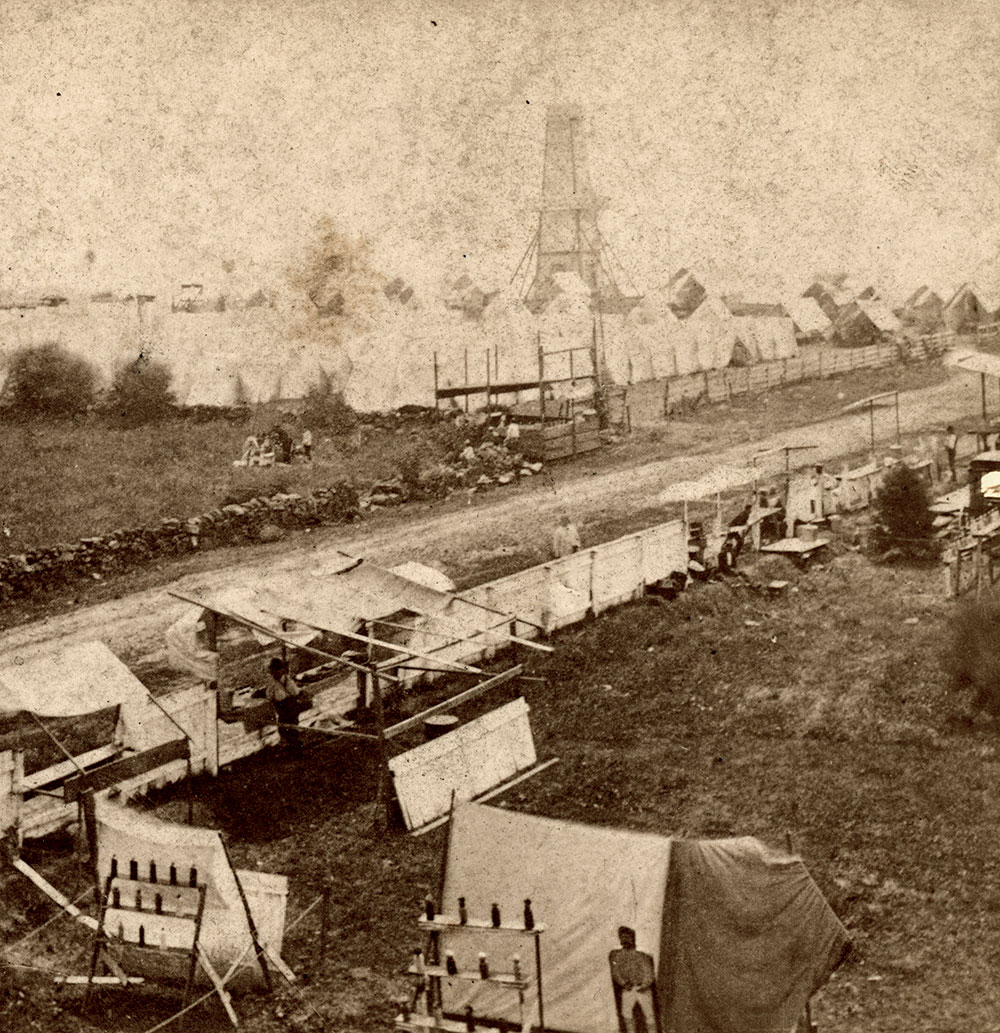

Epilogue

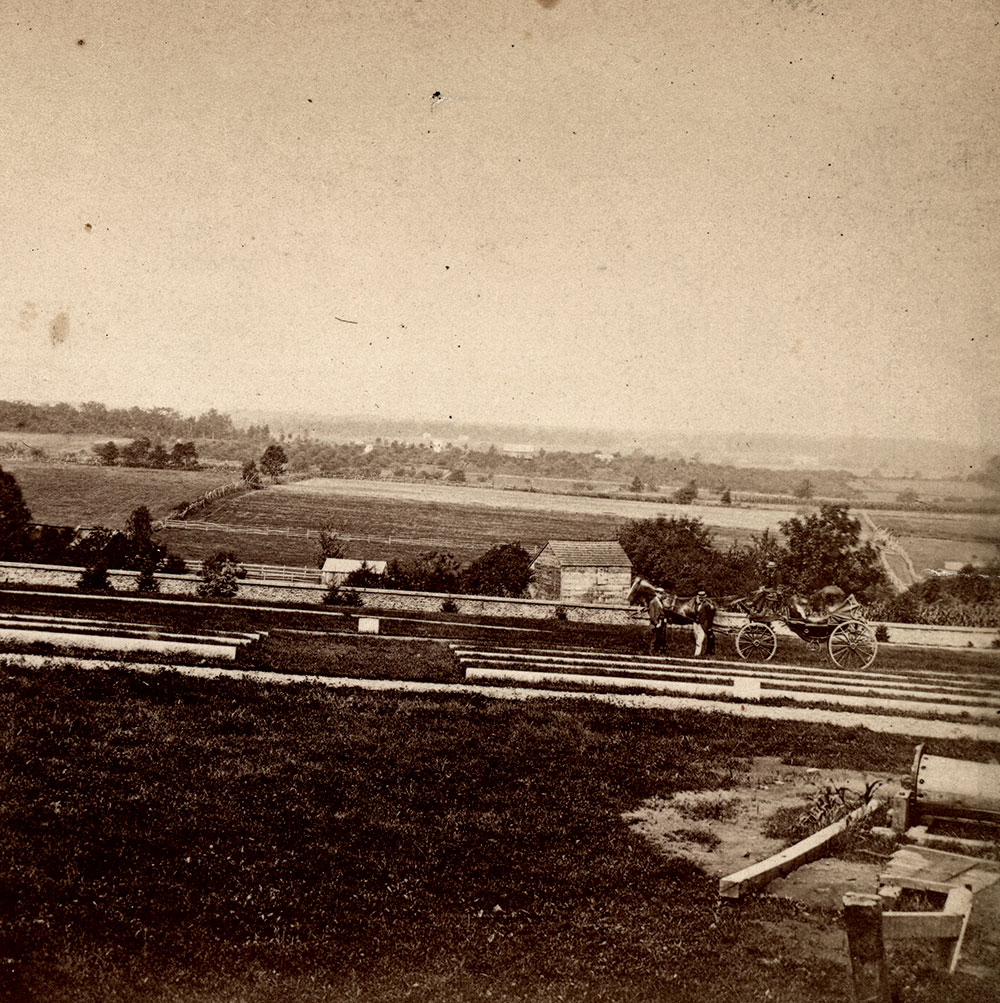

By the time of the reunion of Cowan’s men and their photograph in the Cemetery, its key geographic feature had been compromised. Bachelder articulated the problem in the 1883 edition of his guidebook. The once open field that “commanded an unobstructed view of the surrounding country” had been “covered with a heavy growth of ornamental trees,” resulting in “beautiful shrubbery at the expense of a magnificent landscape view.” The shrubs and trees that were part of the original plan by architect Saunders matured and were, over the years, added to so that the viewshed that once helped win the battle for the Union is now available only through a study of stereoscopic panoramas taken in the summer of 1869 by local photographers William Tipton and Charles Myers.

Nevertheless, modern visitors are encouraged to walk the grounds, perhaps armed with a copy of this issue. Lingering among the gravestones of the soldiers mentioned here, one can keenly appreciate what the editors of Harper’s Weekly expressed in April 1864: The Soldiers’ National Cemetery “marks at once the terrors of that bloody field, and a nation’s gratitude to those who there gave their lives to its defense.”

Special thanks to Garry E. Aldeman, Sue Boardman, John Richter, and Timothy H. Smith for their valuable insights and assistance in identifying the unpublished stereo view of Samuel Weaver painting the gravestones in the Cemetery.

References: Bachelder, Gettysburg: What to See and How to See It; Bachelder, Gettysburg Publications; Ladd, John Bachelder’s History of the Battle of Gettysburg; Souder, Leaves from the Battlefield; Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg, The Aftermath of a Battle; Faust, This Republic of Suffering; Frassanito, Early Photography at Gettysburg; Busey, The Last Full Measure: Burials in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg; Weeks, Gettysburg: Memory, Market and An American Shrine; Klement, The Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery and Lincoln’s Address; Gottfried, Lincoln Comes to Gettysburg: The Creation of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address; Cole and Frampton, Lincoln and the Human Interest Stories of the Gettysburg National Cemetery; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Revised Report of the Select Committee Relative to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery; Warren, Battle Recollections: What I Saw Before, During, and After the Battle of Gettysburg; Campbell, “The Aftermath and Recovery of Gettysburg, Part 2,” The Gettysburg Magazine (January 1995); Bearss, “If I Had One Last Day to Spend at Gettysburg,” The Gettysburg Magazine, Issue No. 48; Guelzo, “The Unturned Corners of the Battle of Gettysburg: Tactics, Geography, and Politics,” The Gettysburg Magazine, Issue No. 45; Georg, “This Grand National Enterprise”: The Origins of Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery & Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association; Root and Stocker; Isn’t This Glorious!: The 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments at Gettysburg’s Copse of Trees; Shultz, Double Canister at Ten Yards: The Federal Artillery and the Repulse of Pickett’s Charge; Gottfried, The Artillery of Gettysburg; Eddy, History of the Sixtieth Regiment, NYS Volunteers; Muffly, The Story of Our Regiment: The History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers; Letter, S. Boardman to Charles Joyce, January 2019; Griffing, Spared and Shared; Charles A. Foss Letters, Charles T. Joyce Collection; Erastus Harris-Rachel Smith Correspondence, Gowanda Area Historical Society; Kyle Stetz Correspondence with Charles Joyce, February, 2021; Fuller, Personal Recollections of the War of 1861; The Reunion of Cowan’s Battery on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, July 3rd, 1886, the Twenty-Third Anniversary of the Battle, with a Sketch of the Battery from 1861 to 1865; Stephen B. Rodgers to Wes Small, February 2, 2004.

Charles T. Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

4 thoughts on “A Place of Pilgrimage for the Nation: A photographic tour through Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery”

Comments are closed.