By Kurt Luther

Last autumn, I visited Vermont for a week of hiking during peak foliage season. It was my first time stepping foot in the Green Mountain State since the summer of 2009, when I drove up to the town of Brattleboro for a sneak preview of Ken Burns’ new documentary series, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.

The series has many Civil War connections, some more obvious than others. One segment focuses on the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871, the first federal survey of the region that would, a year later, become Yellowstone National Park by the pen stroke of President Ulysses S. Grant. The expedition’s leader, geologist Ferdinand Hayden, was brevetted a brigadier general for his prior service as a Union Army surgeon.

Hayden’s hand-selected team included William Henry Jackson, formerly a private in the 12th Vermont Infantry. Jackson was the expedition’s photographer, and his dramatic images of the Yellowstone region were the first ever captured on camera. According to the National Park Service, his photographs fascinated the public and contributed to Yellowstone’s designation as a national park, and “Jackson’s name became a household word.”

A decade earlier, Jackson was a teenager and an aspiring artist. He grew up in Georgia and Troy, N.Y., where, in 1858, photographer C.C. Schoonmaker hired him as a retouching artist. In 1860, Jackson moved to Rutland and was hired on as an assistant by photographer Francis Mowrey. According to the International Photography Hall of Fame, the job with Mowrey “was the perfect experience for Jackson.” He advanced his skills from retouching to full-color tinting and learned more about darkroom techniques and equipment.

Around this same time, the Civil War was erupting across the country. Jackson would enlist in 1862. But for a couple of years, he worked in Mowrey’s studio and helped create photos for other soldiers going off to war. I was curious to see what these Civil War portraits looked like during Jackson’s tenure.

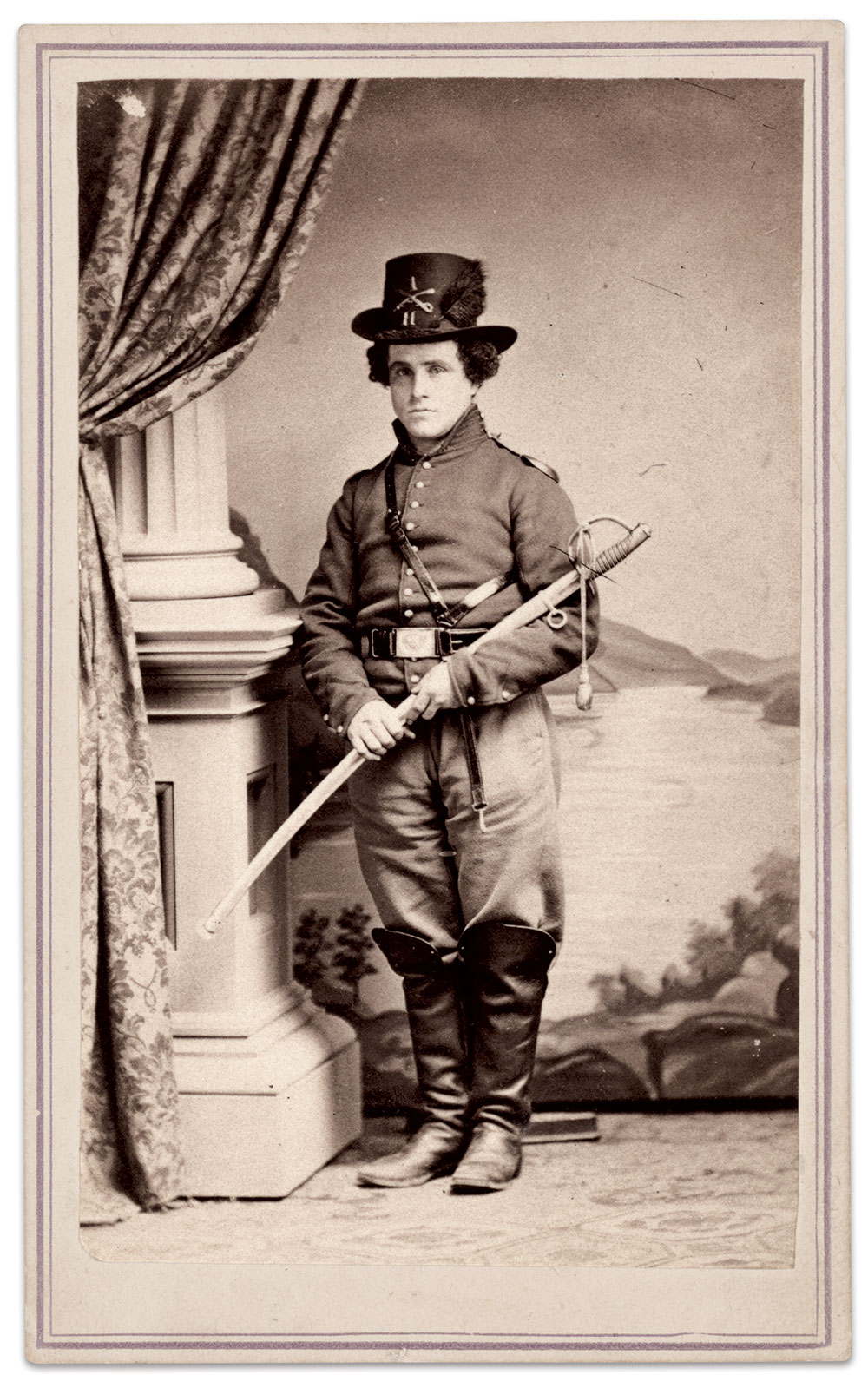

The Library of Congress shows a single search result for photos credited to Francis Mowrey. The photo is a carte de visite of an unidentified Union cavalryman. The stocky young man wears a shell jacket with a high collar and shoulder scales suggesting an early war uniform. Unadorned sleeves indicate the rank of private. He cradles his scabbarded saber in both hands, and his trousers are tucked into a pair of riding boots. He is clean-shaven with a slightly cleft chin and bushy dark hair. He wears a black regulation dress hat, including an ostrich feather, hat cord, and a complete set of brass. Beyond the crossed sabers branch insignia, the regimental numeral “1” and company letter “H” suggest intriguing possibilities for research.

The young trooper stands beside a prop column and curtain with a floral pattern. Behind his posing stand, a painted backdrop reveals a landscape scene featuring mountains, trees and a prominent body of water. Photo sleuths typically associate this backdrop scene with Vermonters, and the mount’s backmark, crediting “F. Mowrey” of Rutland, removes all doubt. The carte’s mount also includes a double border on the front of an unusual purple hue, and an elaborate yellow and purple design on the back featuring a patriotic eagle illustration. There is no tax stamp.

The Library of Congress’s catalog description connects the dots and asserts that the unknown soldier is a member of “Co. H, 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment.” A note adds, “Seller indicates that photo came with 19th century note reading ‘I think that this is father’s cousin Byron.’” Armed with this rich set of clues, I embarked on my photo sleuthing journey, feeling optimistic that the young man could be identified.

I began by investigating soldiers with first or last name “Byron,” who served in the 1st Vermont Cavalry. While both the assumption of a Vermont regiment and the Byron annotation could prove inaccurate, these leads offered a starting point. I expected they would quickly suggest a first slate of candidates that a deeper dive into service records and references could confirm or debunk.

However, this trip down the sleuthing trail was bumpier than I expected. First, I visited the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) and clicked on the “Personnel Directory” feature. The context for the period inscription suggested that Byron was most likely a first name. But just to be safe, I searched both first names and last names of soldiers with Vermont service.

Forty-one Vermont soldiers had the first name Byron. Inspecting each of these, I found two members of the 1st Vermont Cavalry, but their details diverged from the unidentified trooper. Instead of Co. H, Pvt. Byron Collins served in Co. M, and Pvt. Byron Eagar served in Co. B. Furthermore, both soldiers first enlisted in 1864, longer after most cavalrymen, especially in long-serving units like the 1st Vermont, abandoned uniform flourishes like the ostrich plumes and shoulder scales pictured in the photo.

Likewise, there were only two results for the surname Byron, and neither was a good fit. While both soldiers served in a Co. H, the same as our mystery man, they were in infantry units, not cavalry, and the regiment numbers differed. Pvt. Thomas Byron served in the 3rd Infantry, while Pvt. Oscar Byron served in the 6th Infantry.

While these initial results showed no matches for a trooper named Byron in the 1st Vermont Cavalry, I was not yet ready to rule out the possibility. HDS is an invaluable research tool, but among its millions of database entries, occasionally there is an error or omission. Many photo sleuths cross check HDS results with the National Park Service’s Civil War Soldiers & Sailors Database; occasionally, a name appears in one database but not the other.

I visited the NPS site and typed Byron into the search bar. With three clicks, I easily narrowed the results to Union cavalry units from Vermont. Besides Pvt. Collins and Pvt. Eagar (spelled “Eager” here), whom I had already ruled out from HDS, I saw a third name: Byron O’Shea. I clicked it and my excitement grew. O’Shea was a private in Co. H, 1st Vermont Cavalry. Apparently he also went by the alternate name “Bryan Shea,” so my HDS search for Byron had overlooked him.

As I dug deeper, my excitement dimmed. An HDS entry for Bryan Shea revealed that he enlisted in mid-1864, only to desert the following year. As with Collins and Eager, Shea’s late-war enlistment seemed at odds with the mystery trooper’s elaborate uniform, though I could not rule it out. The best evidence would be visual confirmation using an identified reference photo of Shea, but, despite my best efforts, I could not locate one. HDS had none, and the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center’s MOLLUS-Mass collection, a reliable source of New England Civil War soldier portraits, also came up empty.

Fortunately, beyond these general collections of Civil War portraits, there was also a promising state-specific resource: Vermont in the Civil War (vermontcivilwar.org). Its website describes it as “a grassroots project documenting the story of [Vermont’s] contributions to the war, and what happened to the participants during and after the war.” Nearly 40,000 such individuals’ stories are cataloged on the site. Every Vermont Civil War military unit has a section; I navigated to the one for the 1st Cavalry, and then to the roster of its members.

I was presented with an alphabetized list of more than 160 profiles of members of the unit, many with wartime portraits. I scanned the names for Bryan Shea but found no match. My search for Byron O’Shea was equally unsuccessful. I had hit another brick wall—and all of my efforts so far relied on a period inscription’s hazy recollection about “father’s cousin Byron.”

Frustrated, I was close to abandoning Byron altogether, and starting down a different path. As a kind of Hail Mary, I used my browser’s “Find in page” feature to search the 1st Vermont Cavalry profiles for anyone with that name. I was surprised to find a single match: James Byron Holden.

I clicked the link, and the top of the profile indicated that Holden was a private in Co. H. So far, so good. Scrolling down, I was greeted by two photos from the private collections of John Gibson and Dennis Charles. Both were identical copies of the Library of Congress photo of the mystery trooper. I had found my man.

The final section of the page reproduced an excerpt from an 1862 edition of the Rutland Daily Herald, courtesy of Tom Boudreau, stark in its brevity: “Byron Holden, private, shot through the hips. Died in Hospital at Strasburg, May 26th.”

I wanted to learn more about Byron Holden–by now all too clear that he went by his middle name–beyond this single sobering sentence. Despite the 1st Vermont Cavalry’s participation in 75 battles and skirmishes, capturing “three battle flags, thirty-seven pieces of artillery, and more prisoners than it had men,” according to its own 1st Lt. William Greenleaf, no regimental history was written by contemporaries beyond his short article. Joseph Collea’s The First Vermont Cavalry in the Civil War, published in 2010, fills this gap and illuminates Holden’s relationship with his fellow troopers and his final moments.

According to Collea, “the death of James Byron Holden touched a special chord in Company H.” Private Holden, age 23, mustered into the 1st Vermont Cavalry in November 1861. Six months later, on May 24, 1862, he was mortally wounded near Middletown, Va., during Nathaniel Banks’ retreat from the Stonewall Brigade. Holden’s bunkmate, Pvt. Harley Peterson, accompanied him to Strasburg, where captured medical staff of the 1st Maine Cavalry eased his suffering. When his comrades were able to return a few weeks later, they learned his fate from a wooden grave marker. Capt. Selah Perkins, Holden’s commander, remembered him as “brave, quiet, and true.”

Holden’s possessions, including a bullet-riddled blanket, were forwarded to relatives in Clarendon, Vt. His wife Elizabeth died just two years later in December 1864. Despite his wish to be laid to rest in Vermont, the war intervened, and Holden remains buried at Winchester National Cemetery.

Examining the carte I now knew depicted Byron Holden, I wondered if he had encountered William Henry Jackson when he stood for his photograph in Mowrey’s studio in Rutland, just a few miles down the main road from Clarendon. Perhaps Holden’s smart uniform and solemn pride that day–or the local newspaper’s account of his courageous sacrifice not long after–helped inspire Jackson to enlist a year later.

In the moment when this photo was taken, Holden’s and Jackson’s lives were both full of possibilities. The war transformed them. For Jackson, the adventure was just beginning. He became a world-famous artist and photographer who traversed the American West documenting his subjects. When he died in 1942, he was one of the last remaining Civil War veterans.

Holden’s experience could not have been more different. One of the first men in his regiment to be killed, his opportunities for fame and fortune were tragically cut short. Yet, by identifying this photo of Byron Holden, preserving it in a public archive, and telling his story, we ensure that his memory lives on.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more