By Mark Savolis and Ronald S. Coddington, featuring images from Mark’s collection

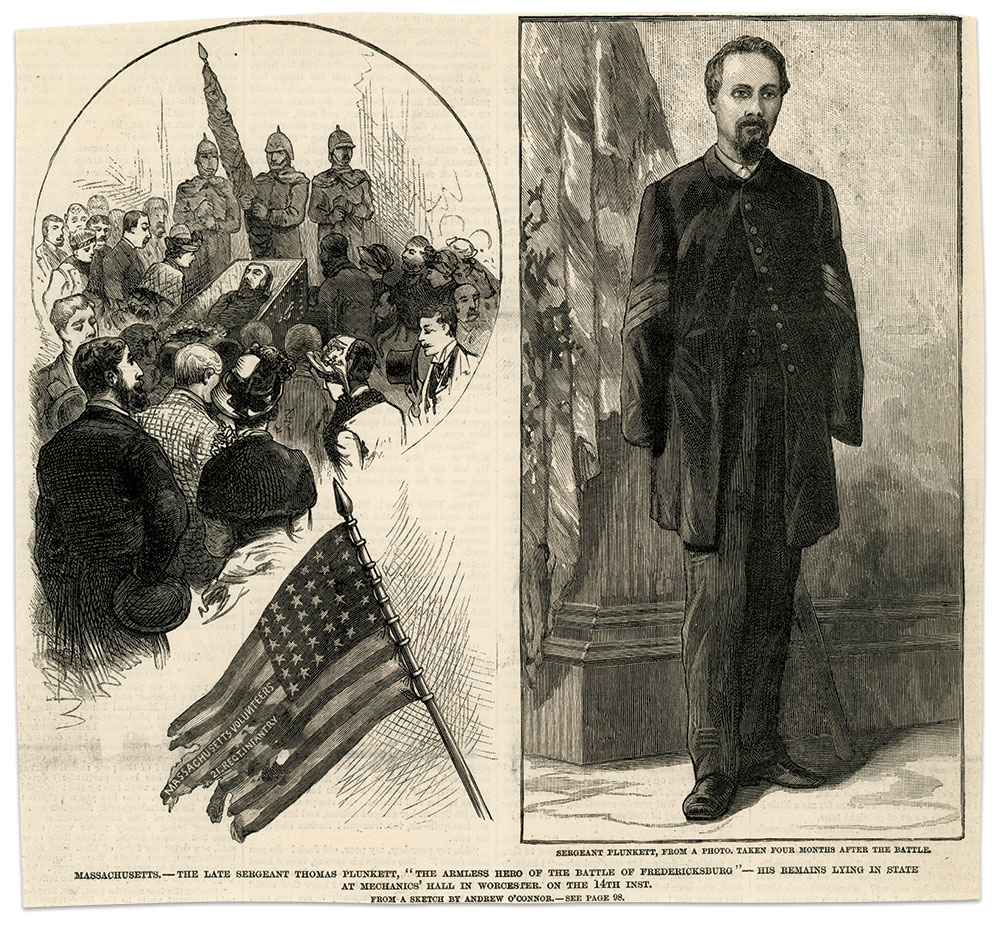

At Fredericksburg, a wave of Massachusetts volunteers charged towards Confederates entrenched along a stone wall on the crest of Marye’s Heights. As they double-quicked it up the slope against a hail of fire, a bullet struck the color sergeant. The bearer and the Stars and Stripes toppled to the ground.

The advancing infantrymen, members of the 21st Massachusetts, swept towards the rising crescendo of shot and shell. The slumped figure of the sergeant and the flag lay where they fell. One of the Bay State boys, Tom Plunkett, a dependable man stationed in the rear of the regiment to prevent straggling, glimpsed the flag and acted. He threw aside his musket, picked up the pole and banner and rushed to join his comrades.

Tom hailed from County Mayo, Ireland. Born Thomas Francis Plunkett in 1839, he might never have left his homeland. But five years later, following the death of his mother, his father Francis brought young Tom and his brothers to America and settled in Boston. When the Civil War broke out, Tom worked as a boot-maker about 45 miles outside the city in West Boylston, and was engaged to be married.

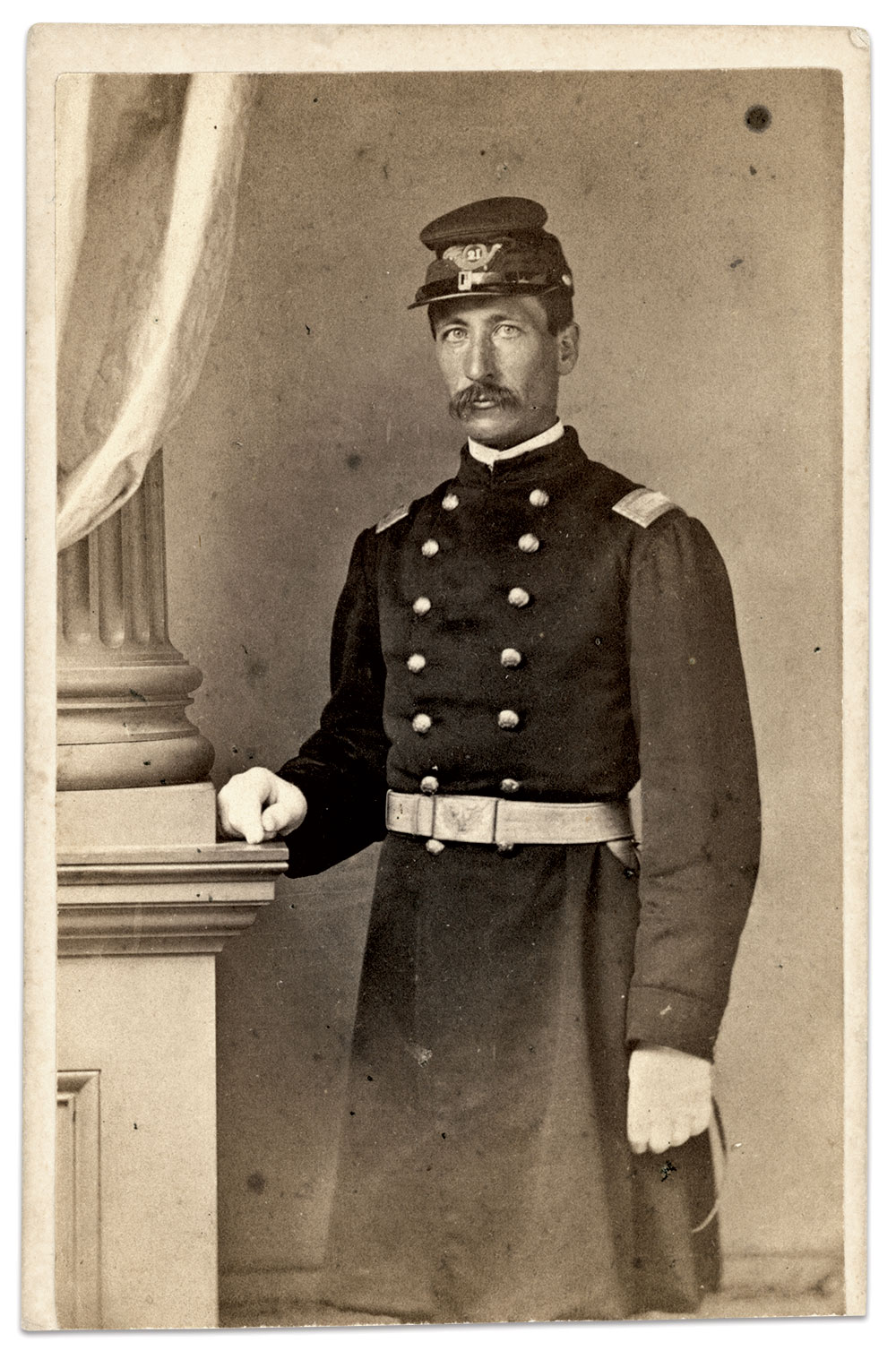

During the first summer of hostilities, Tom enlisted in Company E of the 21st. The regiment mustered and trained at Camp Lincoln in Worcester, where a contingent of ladies presented the men and officers with the national colors. By early September, the regiment had arrived in Annapolis, Md., and became part of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Coast Division. In early 1862, the 21st and the rest of Burnside’s force participated in successful operations along the North Carolina coast.

Months later, in the summer of 1862, Tom’s actions at the Battle of Chantilly established his reputation for gallantry. The 21st, having been transferred to Virginia as part of Burnside’s 9th Corps, suffered 140 casualties in the fight remembered for the death of Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny and a freak thunderstorm.

Towards the end of the engagement, after the regiment withdrew from a wooded area, Tom discovered that a friend and company comrade, Louis Moutte, had not returned. Tom set aside his musket and cautiously entered the woods to find him. He soon happened upon an enemy picket posted behind a tree. Before the rebel turned and spotted him, Tom lunged and grab the man around the back, causing him to drop his musket. Tom pulled back and, pretending to have a revolver, stopped the disoriented picket and grabbed the gun. Tom marched his prisoner out of the woods at the point of the bayonet. Other comrades rescued Tom’s friend, Pvt. Moutte, who suffered a dangerous thigh wound that ended his military service.

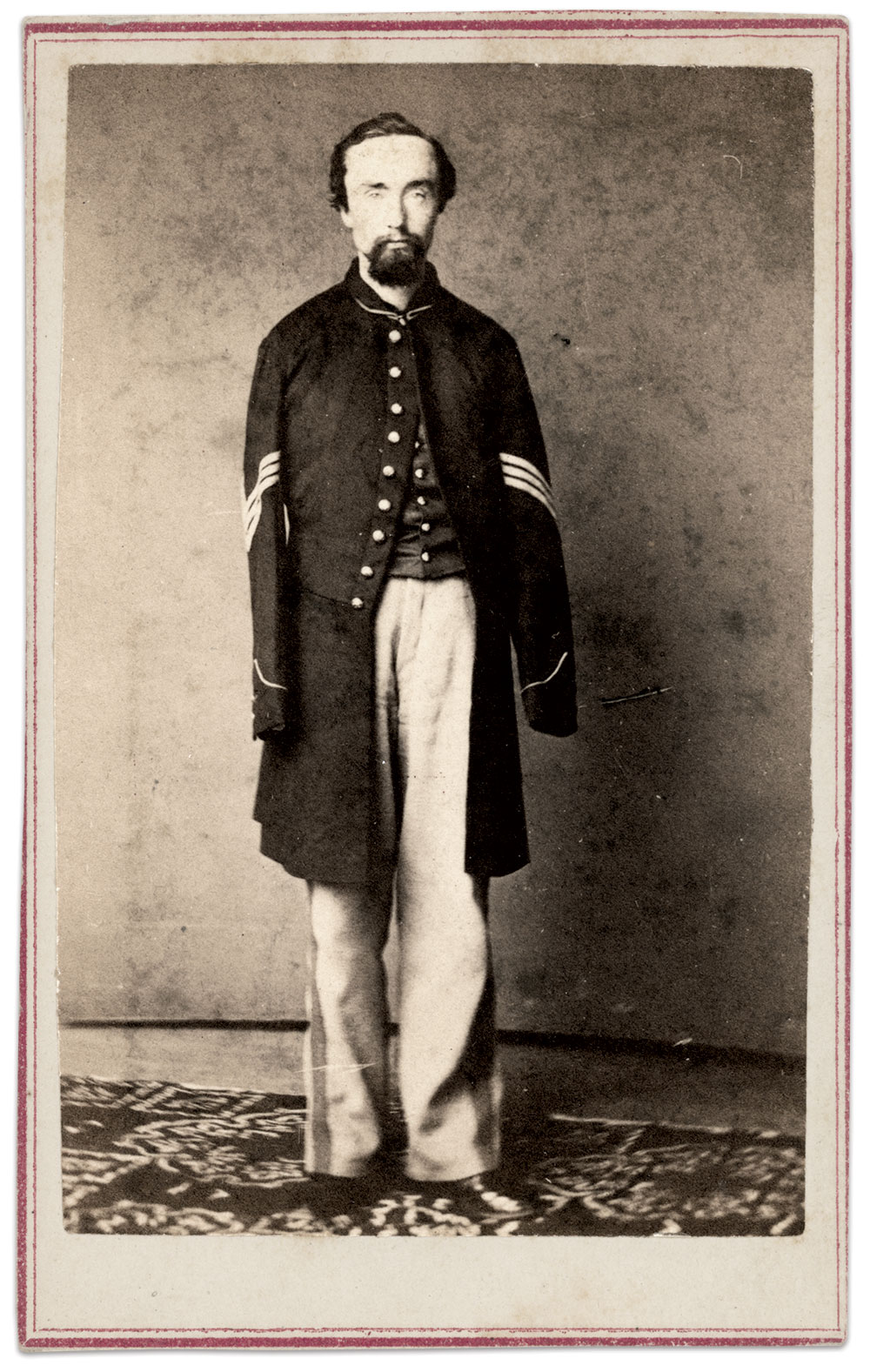

Plunkett received his sergeant’s chevrons for his quick actions.

Less than two weeks later, in Maryland at the Battle of South Mountain, Tom displayed his humanity again. According to a postwar story, during the battle he happened upon a wounded officer sitting and leaning against a barn. The injured man called for water and Tom complied. A brief conversation ensued, during which Tom learned the officer came from Ohio. Tom’s errand of mercy completed, he hurried on to continue the fight.

At Fredericksburg, Tom and his comrades fought an uphill battle against a torrent of fire. The national colors changed hands numerous times along the way. When Tom held them aloft, the fight for the stone wall on Marye’s Heights approached fever pitch. Enemy artillerists poured deadly canister fire into the ranks and rebel infantry peppered them with musket balls. Leaden missiles and projectiles zipped and whizzed around them, some tearing into the ground. Fearful gaps suddenly appeared in the ranks and closed up just as quickly amidst drifts of battle smoke.

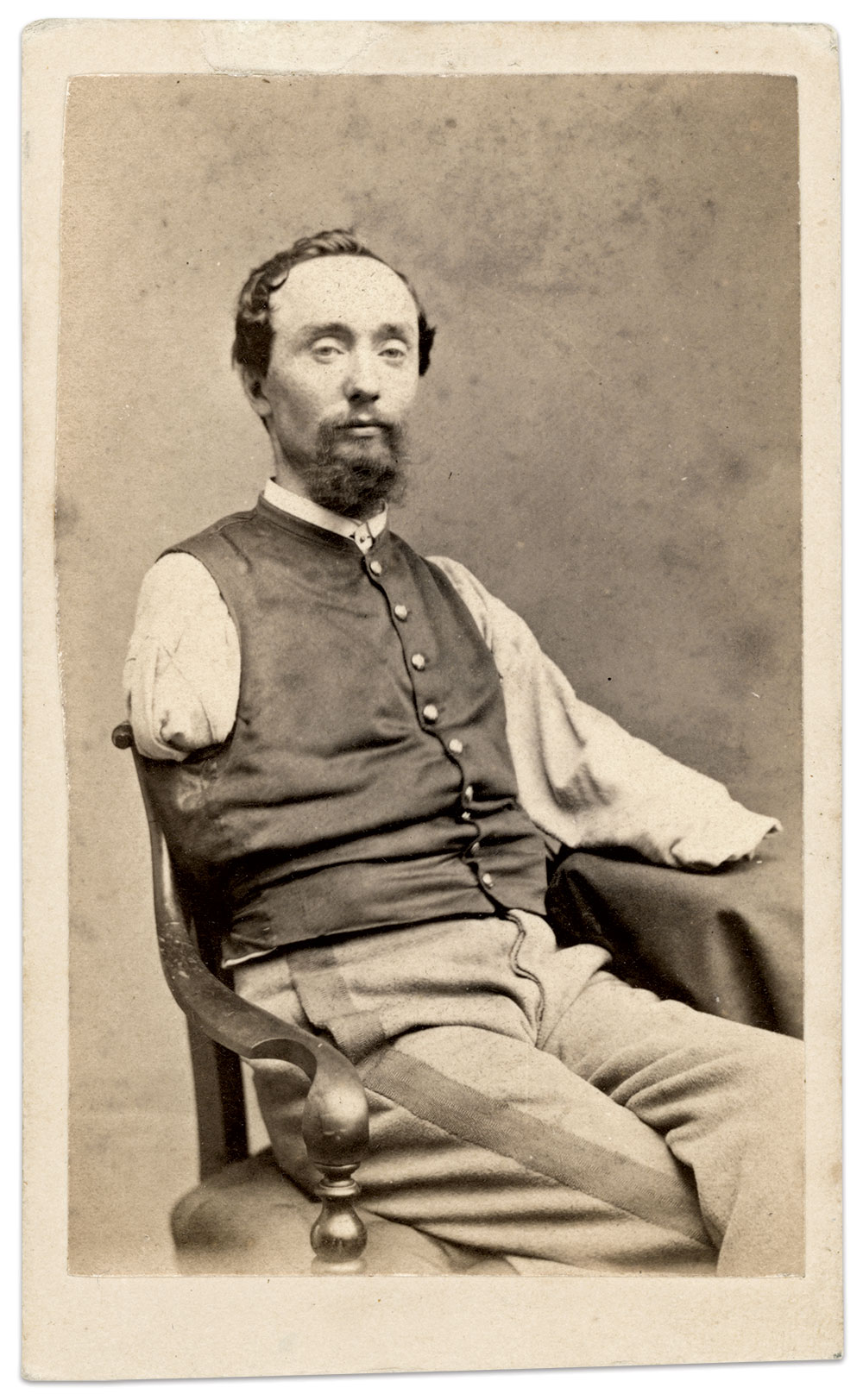

Tom moved forward with the colors, attracting enemy fire. Bullets tore into the banner and pole, and one left a neat hole in his cap. When about 40 rods from the wall, a shell fragment tore into and passed through Tom’s right arm just below the shoulder, glanced off a thick book in his vest pocket and shattered his left forearm near the wrist.

The book, a guide to the Virginia tourist attraction of White Sulphur Springs, had been picked up by Tom earlier that day as a souvenir. It probably saved his life.

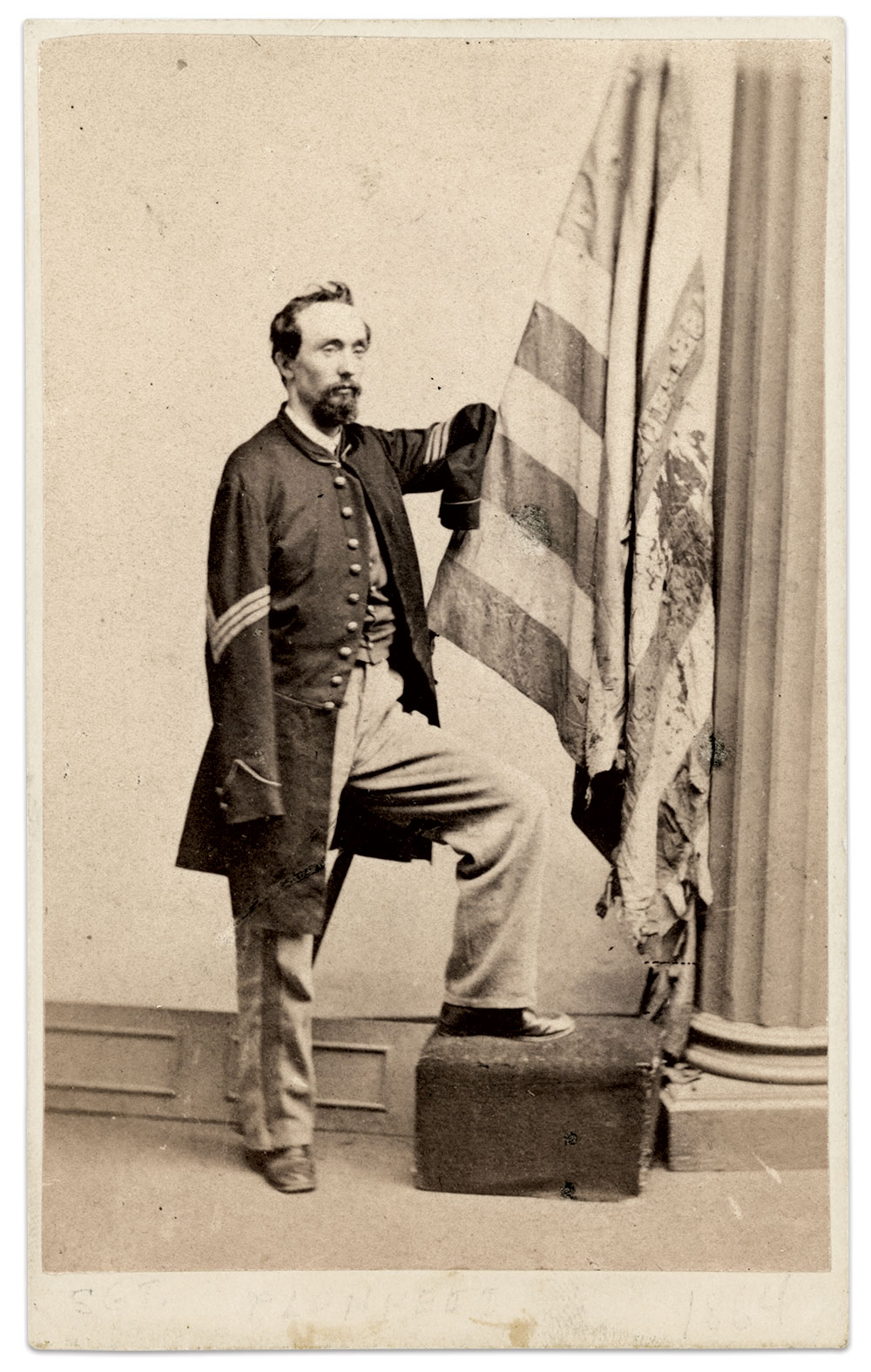

Still on his feet, and bleeding profusely from his mangled arms, Tom planted a foot against the flagpole in an attempt to keep the colors aloft while shouting to his comrades to protect them. His blood left a deep and permanent stain on the silk flag.

The colonel of the 21st, William S. Clark, approached Tom, cut off his accouterments and sent him to the rear. Tom walked until faint from loss of blood, at which point stretcher bearers carried him into Fredericksburg. At an aid station, surgeons determined his case hopeless. They left him on a floor in agony while bloody water splashed on him from surgical operations performed on tables above him. Finally, two hours later, medical personnel administered chloroform and cut away the shredded flesh that were his arms.

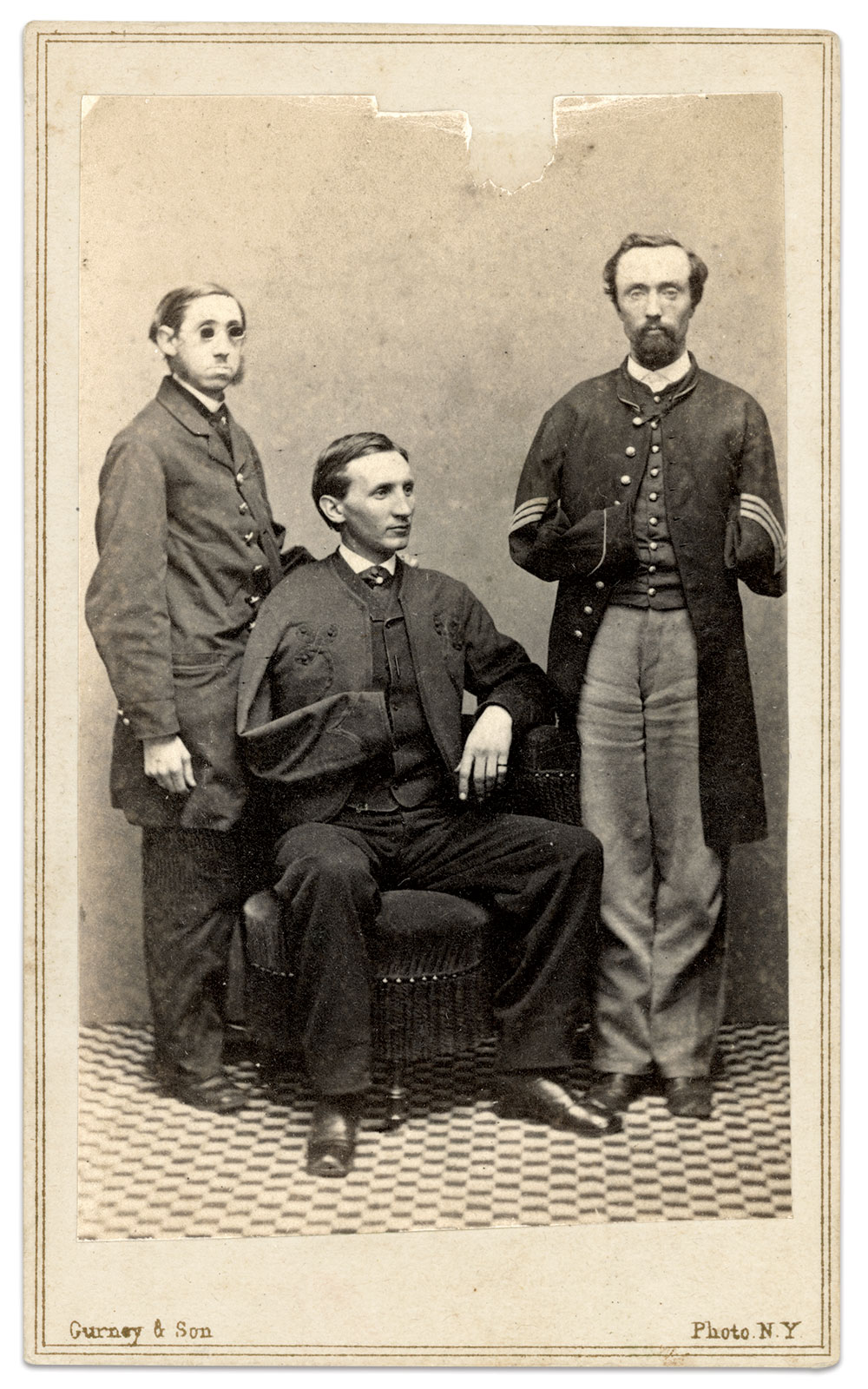

Tom’s condition steadily improved, thanks to the assistance of Clara Barton, who sutured and dressed the stumps of his arms. On Christmas Day, Barton’s 41st birthday, she joined members of the 21st who turned out to salute Tom and other wounded as they left Fredericksburg for Washington, D.C. He transferred to Emory General Hospital for a short stay, then returned home on furlough until discharged on March 9, 1864.

By the time Tom returned to Massachusetts, grateful citizens had collected about $7,000 to support him. He also received a pension, thanks in part to a letter written on his behalf by Barton. With the money, Tom purchased a home in Worcester, a town adjacent to West Boylston. He married Helen Lorimer, and started a family that grew to include three children.

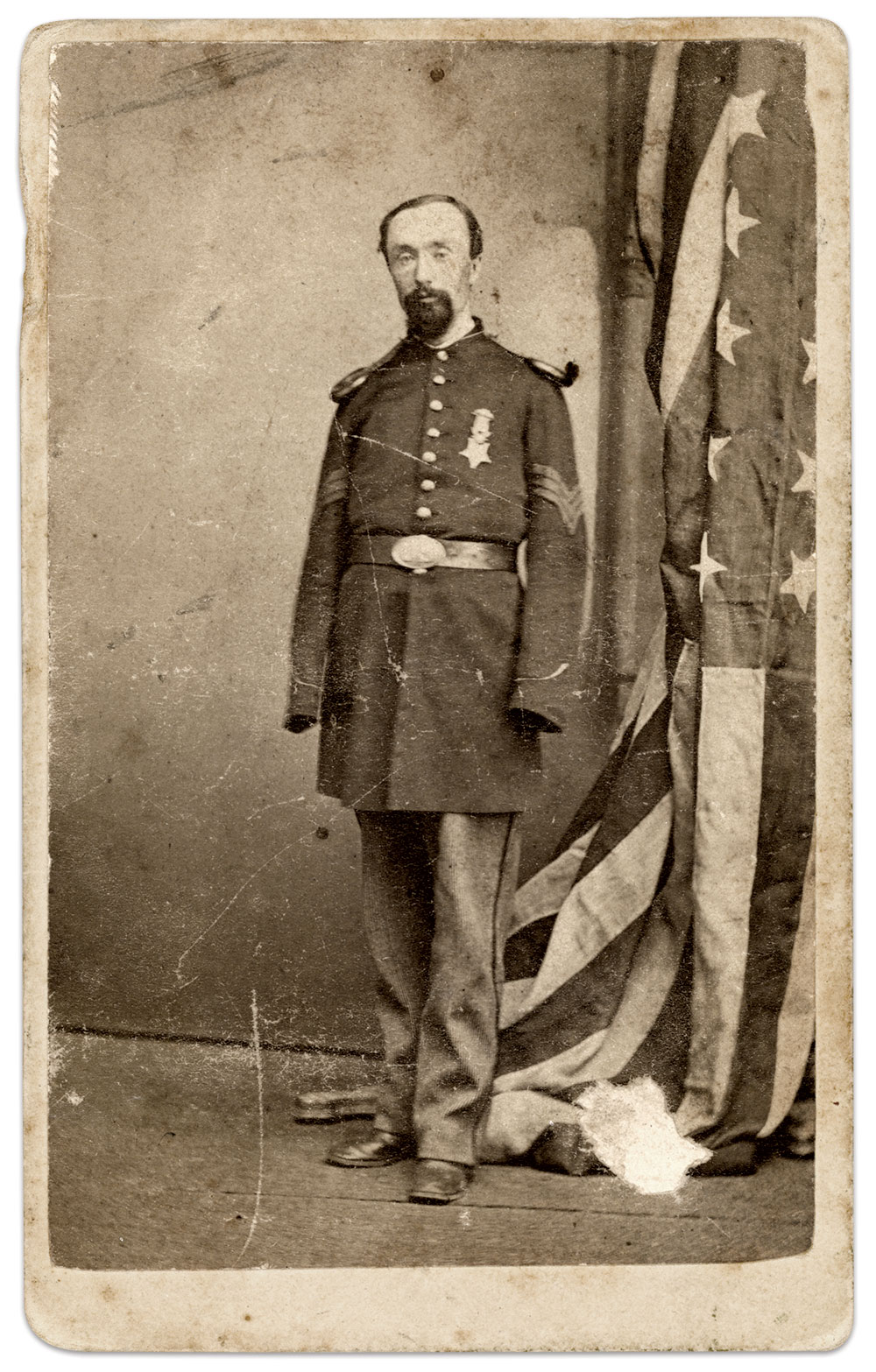

In March 1866, President Andrew Johnson awarded Tom the Medal of Honor. He became a messenger in the Massachusetts State House in Boston, a position he held for 15 years.

Worcester’s civic leaders invited Tom to all its events connected to the Civil War.

In the summer of 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes stopped in Worcester as part of a New England tour and delivered a few remarks to citizens who had gathered. In the crowd stood Tom, who recognized Hayes as the Ohio officer he had assisted 15 years earlier. Hayes had served as colonel of the 23rd Ohio Infantry, part of Burnside’s 9th Corps, and suffered an arm wound at South Mountain.

After the President concluded his remarks, Tom introduced himself. Reacquainted for the first time since the battle, Tom “received from President Hayes, as he grasped the stump of his right arm with both hands, such cordial and sincere expressions of gratitude as only a true soldier can give another.”

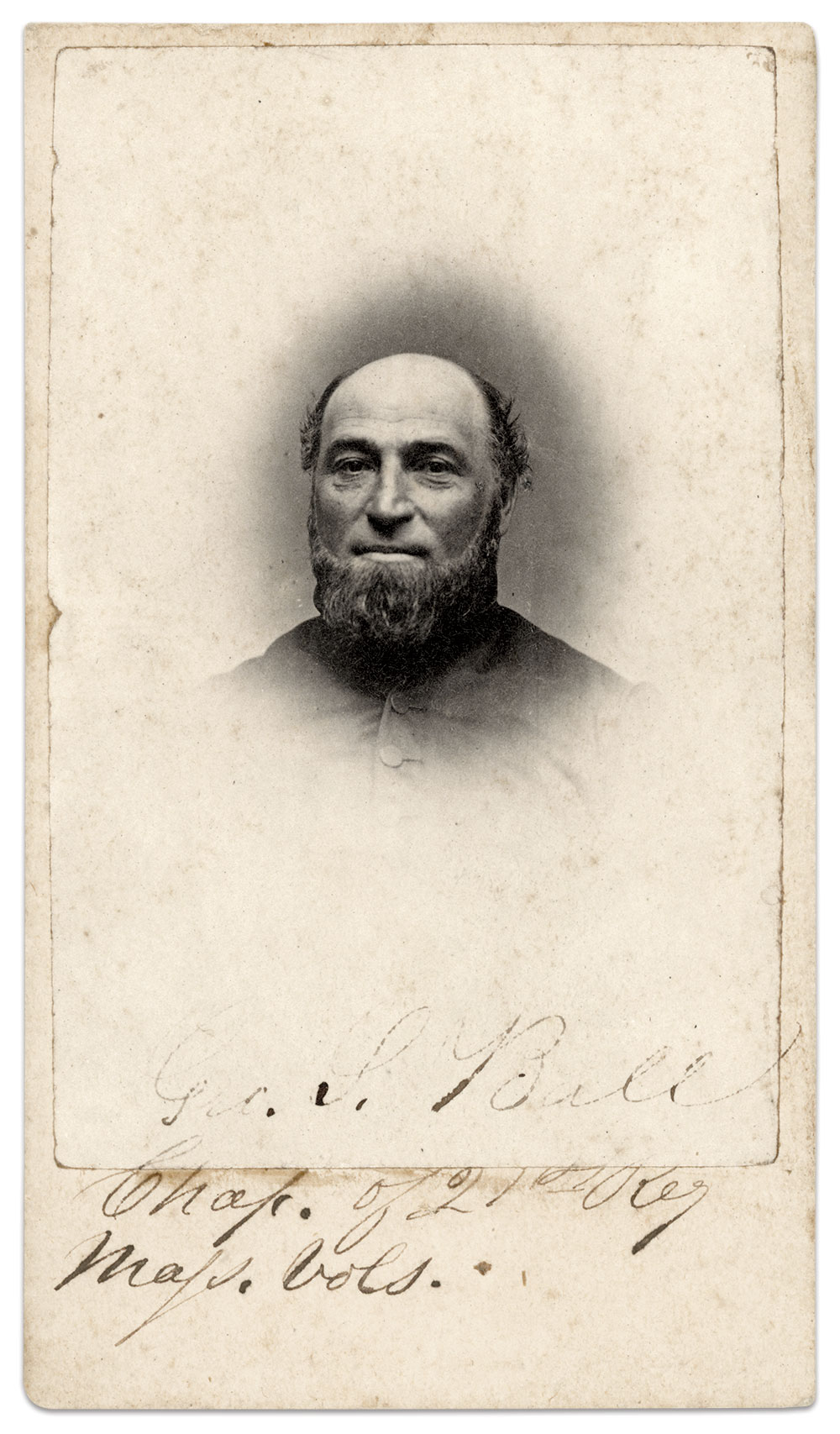

Tom’s health fell into decline in 1884 and he died the next year of inflammatory bowel and stomach disease. (He may have suffered with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s Disease.) Tom was 44. Helen and two sons survived him. A large group turned out for his funeral. Among the pallbearers was the chaplain of the 21st, George Ball. Tom’s remains rest in Worcester’s Hope Cemetery beneath a headstone that includes a draped U.S. flag representing the banner he carried at Fredericksburg.

Dedication: To the late Mike McAfee, with whom I had planned to collaborate on this story.

References: Military service records and pension files, National Archives; The Boston Globe, Feb. 13, 1885; Walcott, History of the Twenty-first Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers; Proceedings in Connection with the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Town of West Boylston, Massachusetts; Barton, The Life of Clara Barton, Vol. I; Williams, Diary and Letters of Rutherford Birchard Hayes; Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums; New York Herald, April 9, 1877; Spears, Old Landmarks and Historic Spots of Worcester.

Mark Savolis became interested in the Civil War in 1962 after a family trip to Gettysburg. He attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester and received his master’s degree in Library Science at the University of Rhode Island. Mark has worked in the archives at the American Antiquarian Society, the Worcester Historical Museum and at Holy Cross. He has been an active Civil War collector since the 1970’s with an interest in central Massachusetts in the war.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““The Armless Hero of Fredericksburg”: The courage and compassion of Medal of Honor recipient Thomas Francis Plunkett”

Comments are closed.