By Kurt Luther

This column’s photo sleuthing story began with an inquiry from Karen Chittenden, Senior Cataloging Specialist in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. Chittenden was processing a new acquisition for the Library, an album of 47 cartes de visite and tintypes of officers of the 48th New York Infantry. Many of the portraits featured period inscriptions identifying the officers, but as an experienced researcher, Chittenden always verified these identifications by comparing them to other known reference photos. However, as she investigated one carte, a vignette of a dark-haired, mustachioed Union line officer with arched eyebrows, she discovered a problem.

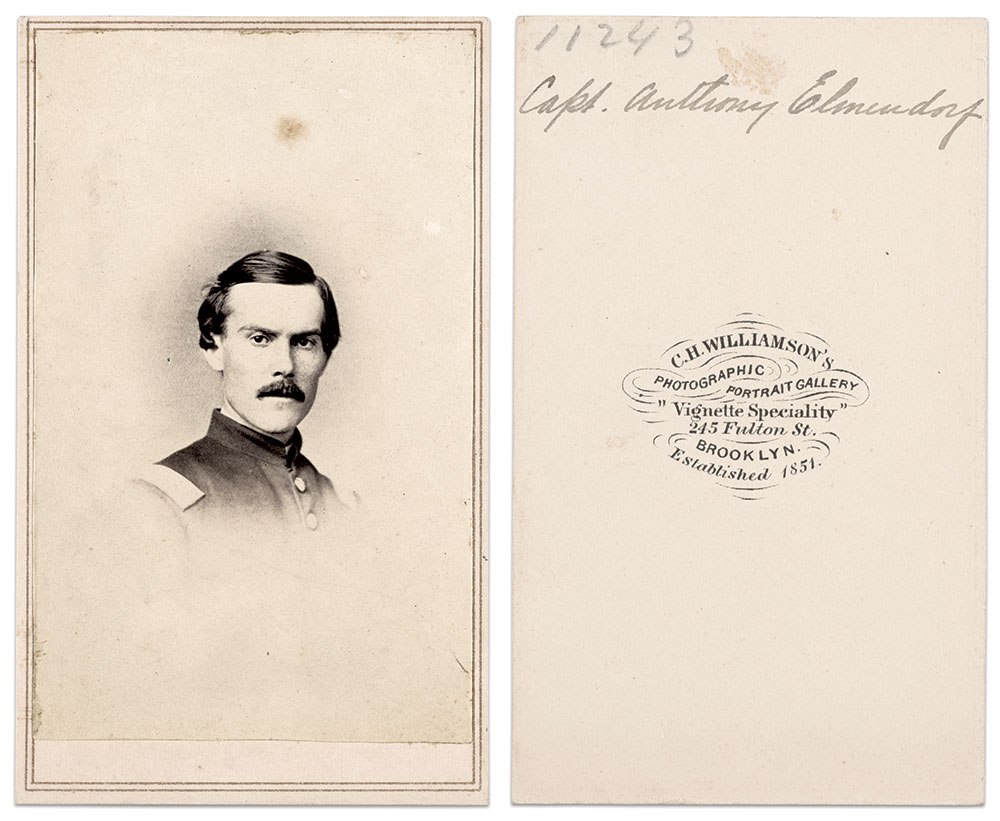

The back of the carte featured the mark of the Brooklyn-based photographer C.H. Williamson and the period pencil inscription, “Capt. Anthony Elmendorf.” Initially, this identification fit, as Anthony Elmendorf enlisted in Brooklyn and served as captain of the 48th New York’s Company G from 1861 to 1864. The difficulty became apparent when Chittenden searched online for reference photos of Elmendorf.

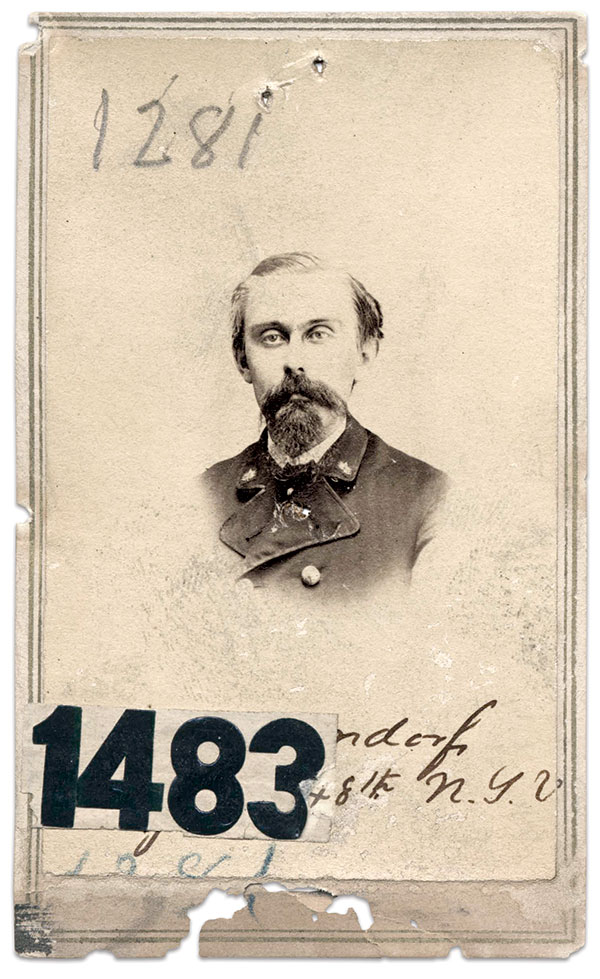

The American Civil War Research Database (HDS) included a photo of Elmendorf, but that photo’s subject looked dramatically different from the man in Chittenden’s mystery photo. The HDS portrait, a carte de visite credited to the New York State Military Museum (NYSMM), showed an officer with deep-set eyes and a goatee. The collar of his field-grade uniform coat bore the oak leaves of a major or lieutenant colonel.

Finally, the front of the carte contained a period inscription that further muddied the waters. It was partly obscured by a large numerical label common to many Civil War portraits that once hung in the New York State Capitol building in Albany. However, two fragments of text were legible: the presumed surname “-ndorf” and regimental identifier “48th N.Y.V.” Despite the contrasting visage and uniform, this inscription suggested that the Elmendorf ID could not yet be ruled out.

Chittenden dug deeper and located a Find a Grave entry for Capt. Anthony Elmendorf’s burial site at Hillside Cemetery, Westchester County, New York, along with two portraits—the NYSMM carte and a second copy uploaded by an anonymous contributor, identical except for lacking the inscription and numerical label. Thus, Chittenden had uncovered two different soldiers, but only one name. Both had period inscriptions suggesting the identity of Capt. Anthony Elmendorf, 48th New York, yet they showed obviously different men. Which one, she asked me, was really him?

I continued Chittenden’s sleuthing journey by researching Elmendorf’s military service. Aside from a three-month stint with the 13th New York Infantry in 1861, he spent the entirety of his Civil War service as captain of Company G, 48th New York. Therefore, Elmendorf could not be the officer pictured in the accompanying photo wearing the insignia of a major or lieutenant colonel. I further reasoned that it should be easier to find more photos of the real Anthony Elmendorf than to identify the photo of the newly anonymous field-grade officer.

Fortunately, I did not have to look far.

The U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC)’s MOLLUS-Mass collection, largely digitized and available online, is one of the best sources of photos of Union officers, especially from Eastern states. I searched Elmendorf’s unique surname and quickly found a copy of the same view as Chittenden’s mystery photo in the Library of Congress. The MOLLUS-Mass copy was identified as “Capt. A. Elmendorf” and surrounded by other 48th New York officer portraits.

The identifications in MOLLUS-Mass tend to be trustworthy, as the collection was originally curated by Civil War veterans and, later, by the professional staff of the USAHEC collections. However, as I have shown in previous columns, even professionally managed collections of Civil War portraits can contain misidentifications, and MOLLUS-Mass is no exception. Since I had already established that the NYSMM’s photo of “Elmendorf” was likely misidentified, I knew that simply pointing to an ID in another archive would not provide a convincing conclusion. Essentially, I sought a “preponderance of evidence” for Elmendorf’s face, ideally from the Civil War years, which would remove any shadow of doubt cast by the original mix-up.

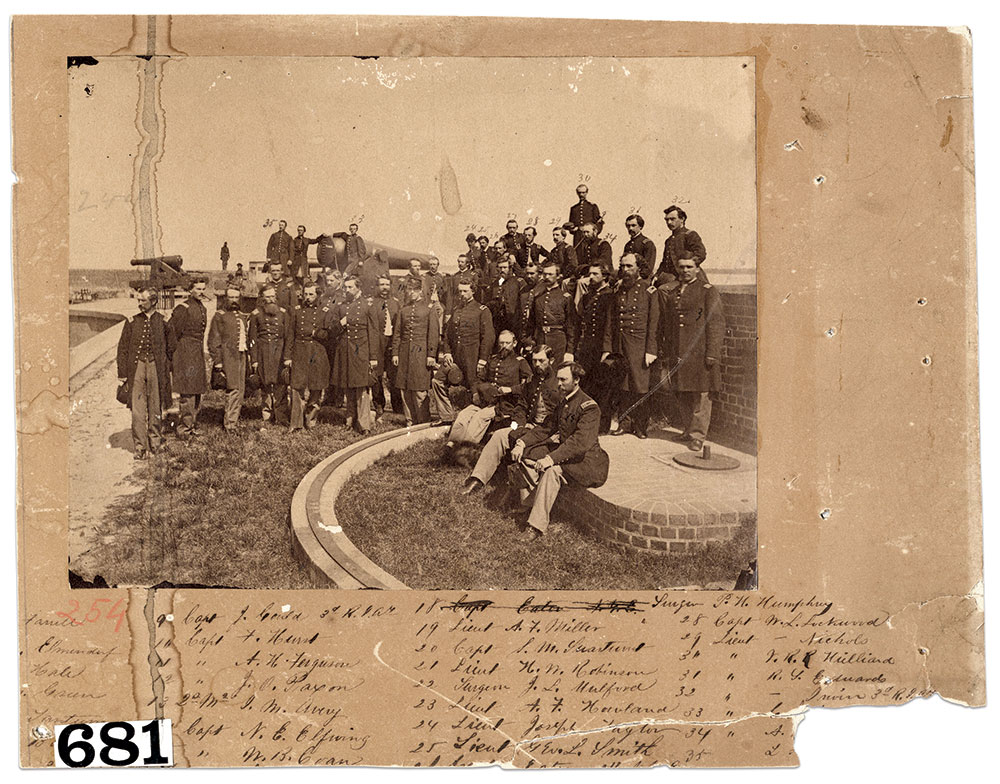

Expanding my search, I checked the next likely place for an Elmendorf photo: a regimental history of the 48th New York. I found a digitized copy of The History of the Forty-Righth Regiment New York State Volunteers in the War for the Union, 1861-1865, published in 1885 by Abraham J. Palmer, formerly a private of that regiment, on the Internet Archive. The book lacked an index, but a list of illustrations near the front of the book promised numerous photos of soldiers. On page 65, I found a remarkable group portrait of 36 officers of the 48th New York, 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery and 1st New York Engineers at Fort Pulaski, Ga.–every one of them identified by name in the caption. A young line officer in the front row, second from the left, was labeled as Elmendorf of the 48th New York.

The man’s distinctive eyebrows and mustache strongly resembled the vignetted officer in Chittenden’s mystery photo and in the MOLLUS-Mass collection. However, the resolution of the scanned page of the regimental history was too low to be sure. Fortunately, I now knew this group portrait of 48th New York officers at Fort Pulaski existed, so I could search for better-quality copies elsewhere.

I found an albumen version in the digitized holdings of the New Hampshire Historical Society. Their high-resolution scan allowed me to confirm that the officer identified as Elmendorf was a facial match to Chittenden’s mystery photo. But this albumen was simply described as “an unidentified group of 36 officers from the 48th New York Infantry Regiment at Fort Pulaski, GA, taken between June 1862 and May 1863” by photographer Henry P. Moore. The individual officers were unnamed.

Thus, this albumen contributed to solving two mysteries at once. It supported the ID of Chittenden’s Elmendorf photo, which, in turn, linked it to the regimental history’s photo naming all 36 officers of this previously “unidentified group.” If I had found the New Hampshire Historical Society photo first, it would not have helped me solve either mystery.

Still, I wanted more reference photos of Elmendorf to make the case for his identification truly airtight. I discovered that the NYSMM collections also held a copy of the Fort Pulaski group portrait, this one identifying the 36 officers in period ink. Coming full circle, I also found several more photos of the 48th New York at Fort Pulaski in the Library of Congress’ collections, one of which included an officer identified with a period inscription as “Capt. A. Elmendorf,” who matches the appearance of the man in Chittenden’s photo. (The ID was not included in the item description, so it didn’t show up in searches of his name.) Finally, I felt I had enough period photo evidence to conclusively identify the mystery photo as Capt. Anthony Elmendorf.

That left the unknown field-grade officer that had, until very recently, been misidentified as Elmendorf in HDS, NYSMM and Find a Grave. Who was he? I downloaded the high-resolution version of the photo from the NYSMM website, hoping that the back of the carte, which HDS omits, might offer some additional clues. Unfortunately, it was blank.

I inspected the front of the carte more carefully, focusing on the inscription partly covered by the label. Could there be a second 48th New York officer whose last name ended in “-ndorf”? I returned to HDS and considered my options. I could not do a wildcard search because HDS requires the user to supply the first letter of the surname, which I did not have. Instead, I would need to manually search the 2,389 soldier names on the regiment’s roster.

I employed several techniques to streamline my search and avoid overlooking the needle in the haystack. First, I brought up the roster for the 48th New York and sorted by the “In Method” column, so that soldiers commissioned into the regiment appeared first, followed by those who enlisted. I reasoned that a major or lieutenant colonel likely entered the regiment as an officer, so this method queued up the most promising candidates. Next, I used my web browser’s “find in page” feature to automatically search each page of results for the fragment “dorf.”

Once again, I need not look very far. On the first page of results, there were two hits for “dorf” surnames. Anthony Elmendorf was no surprise. But the second result sparked my excitement: Charles A. Devendorf. Clicking the link, I learned that Devendorf was appointed an assistant surgeon in the 48th New York in November 1863. In October 1864, he was promoted to full surgeon with the rank of major, and he mustered out the following year. Devendorf’s service record matched the rank insignia of the field-grade officer’s uniform.

Even better, the HDS record included a wartime photo of Devendorf submitted by a subscriber. It showed a Brady carte de visite of a seated Union officer, wearing the first lieutenant’s shoulder straps, dark trousers with gold piping and cap insignia of an assistant surgeon. The man had cultivated a full beard, but his deep-set eyes were unmistakable. The anonymous field-grade officer was Charles Devendorf.

Returning to the newly identified portrait of Devendorf wearing his full surgeon’s uniform, I speculated how it likely came to be misidentified as Elmendorf. The NYSMM cataloger may have read the partial inscription “-ndorf” and “48th N.Y.V,” consulted the 48th New York’s roster, and concluded the search as soon as he or she found the name “Elmendorf,” not considering that another name matching the inscription and, critically, the uniform waited further down the list.

In fact, there was another visual clue pointing to Devendorf’s ID staring me in the face, but I did not recognize it until after reading his military service. Peeking out beneath the label that partly obscured the inscription, where the soldier’s rank was likely written, was the tail of a lowercase “g.” I predict that if a conservator removes the rest of the label, it would reveal the complete word—“Surgeon”—along with the officer’s name, Charles A. Devendorf.

Both Elmendorf and Devendorf survived the war and returned to New York, Elmendorf to explore “mercantile pursuits” and Devendorf to establish a medical practice with his father. Both men eventually moved out west, motivated by poor health—perhaps a consequence of their years of service in the Deep South, a foreign climate to two native New Yorkers. Elmendorf relocated to Big Spring, Texas, to raise sheep. He died of consumption in 1886.

Devendorf moved first to Colorado and then, with his family, to Detroit. He was appointed chair of obstetrics at the Detroit College of Medicine and, later, medical director of the Michigan Mutual Life Insurance Company, a position he held until his death in 1894. His obituary remembered, “His life was devoted to his family and his books; nearly all his spare hours being spent in reading works of scientific and historical value.” Certainly, a sentiment that photo sleuths can appreciate.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.