Introduced by Robert Welch

I am always moved by their faces. As these men and boys stare back at me across more than a century and half’s time, the faces speak the loudest of all. They are largely young men, often defiant, always earnest, sitting for an image for loved ones to hold in their absence. They left for a grand adventure, some never to return, and yet their faces look back at us across the years, begging to be remembered.

Iowa was a young state in 1861, still largely a frontier state with its population concentrated in the eastern third of the land mass, along the Mississippi River and the tributaries that flowed through the heart of the state and into the Father of Waters. The capital at Iowa City was not yet connected to the rest of the nation’s telegraph system, and when President Lincoln called for volunteers after the fall of Fort Sumter, the message had to be carried via rail to Gov. Samuel Kirkwood. An often repeated yet hard to truly verify story claims that the messenger found Gov. Kirkwood working in his garden, dressed in boots and work clothes. Upon reading the telegram, the man soon to be known as Iowa’s “war governor” wondered aloud if he could fill the one regiment quota that the federal government had placed on the state.

Kirkwood’s fears were unfounded; volunteers flooded into the camps of instruction established in Keokuk, Davenport, Dubuque and eventually every major city in the state. By 1865, 76,534 Iowans served in 44 infantry regiments, four artillery batteries, and nine cavalry regiments.

Those Iowans participated in every theater of operation served by the U.S. Army save the extreme West in New Mexico or the Pacific Coast. In the rush to secure the disputed lands of Missouri and the Mississippi Valley, those first Iowa regiments went to support generals Nathaniel Lyon and Franz Sigel in Missouri. More regiments marched under Maj.Gen. Samuel Curtis, Iowa’s former Senator, as he marched into northwestern Arkansas to tighten the American hold on Missouri. They held the line at Shiloh and waited for Vicksburg to fall to Grant. They marched to Atlanta, Savannah and Washington with Sherman. And Iowans fought in Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah, chasing Jubal Early out of the Valley.

Iowa’s soldiers represented a cross-section of the American people in many ways. One thing that has always struck me when searching through the Roster and Record of Iowa Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion is how few of these men and boys were actually born in the state. Published from 1908 through 1911, the six-volume series records the names and service histories of all the members of the state’s regiments. The rosters show men born in nearly every state of the Union, as well as Canada and Europe. Perhaps my favorite birthplace noted in the records remains that of Edward H. Mix of Company C, 3rd Infantry. Noted simply as “at sea,” Mix is one of many born aboard ship as his parents sought a better life in a new land. No matter where they were born, the numerous birthplaces found in the records symbolize the vast mobility of the 19th century, a nation, a people on the move.

They are America, and they stood when called upon to save the Union.

— Robert Welch

1861

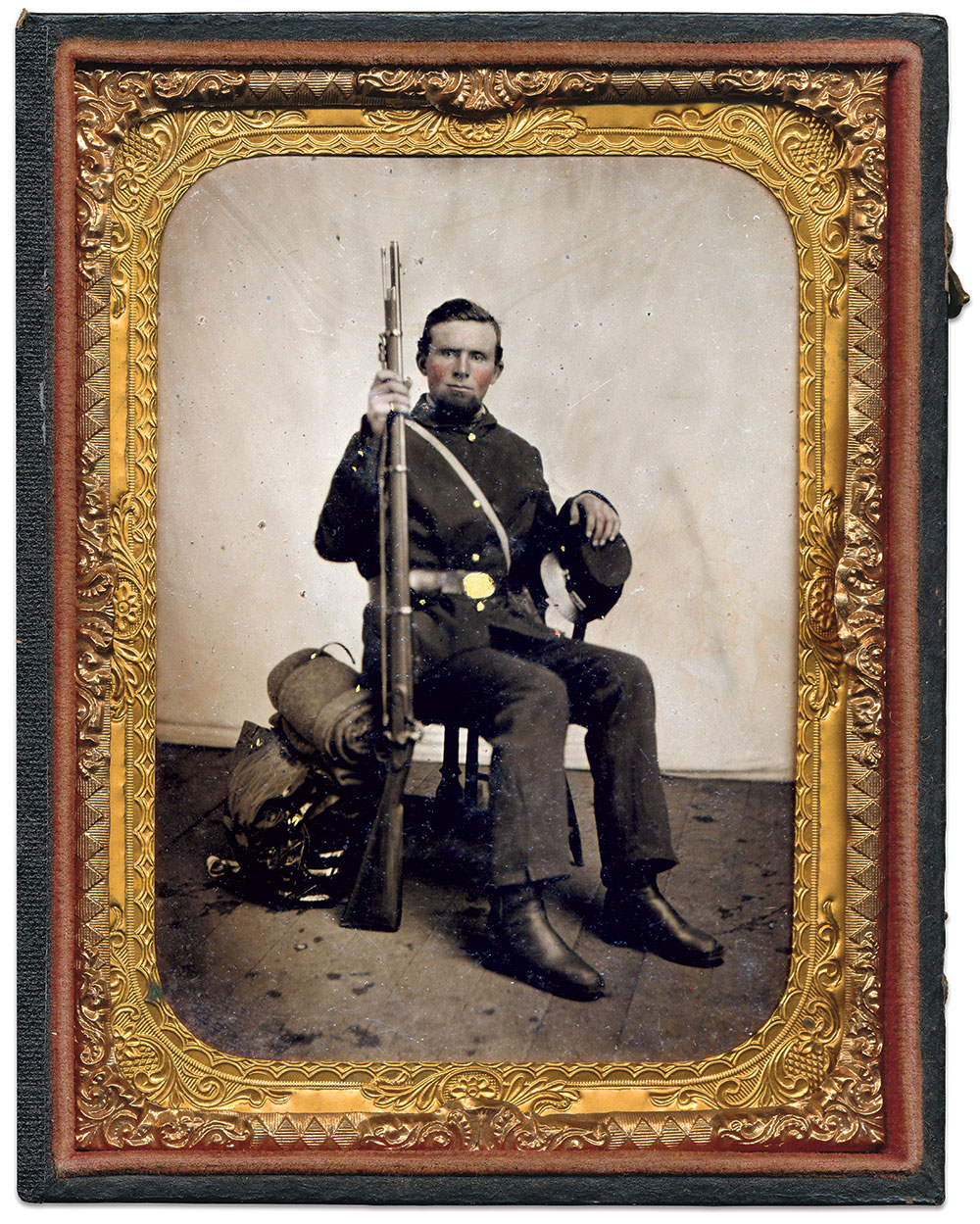

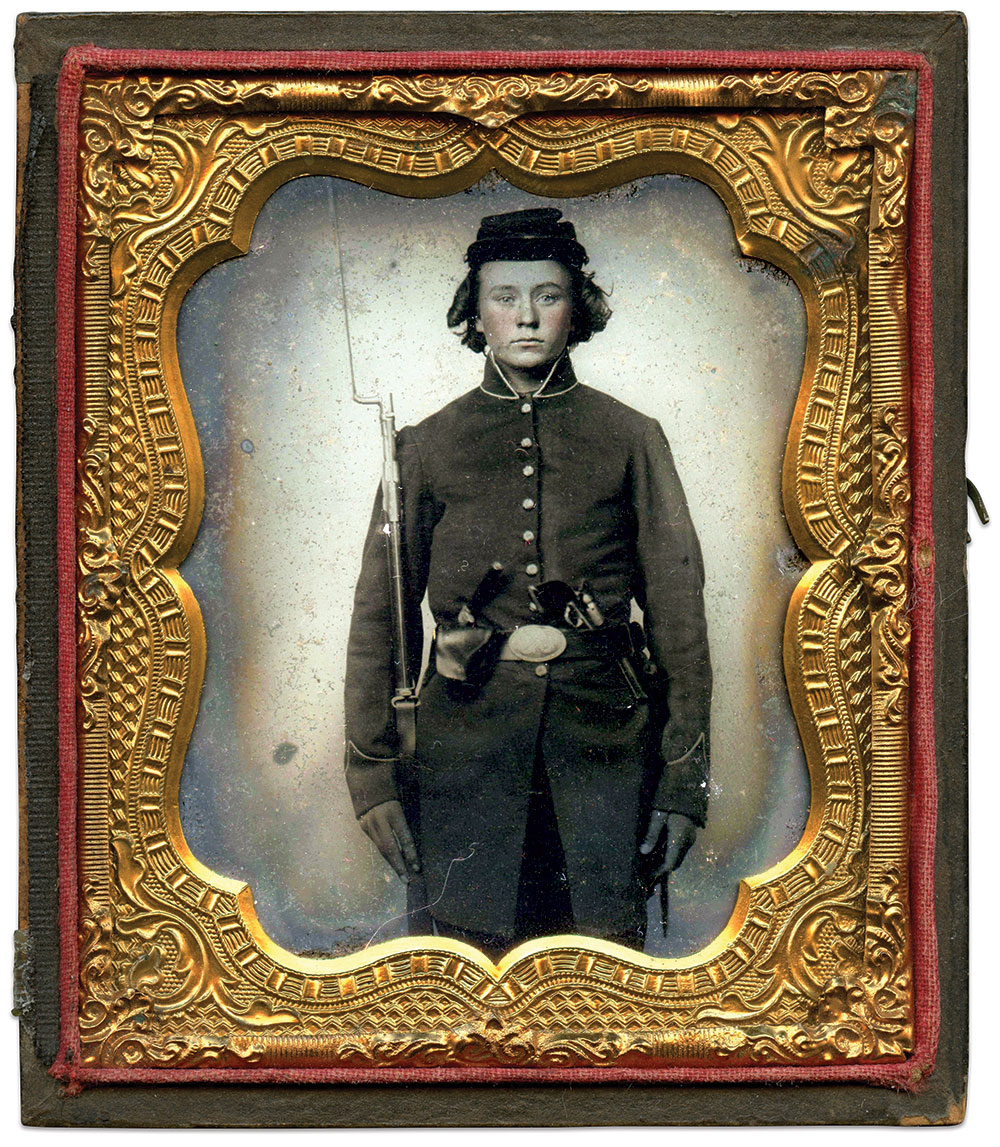

Quintessential Infantryman

George S. Durno looks the part of a classic American infantryman. The 23-year-old Scottish immigrant from Postville, Iowa, posed with new equipment and an Enfield rifled musket, joined the 12th Iowa Infantry in September 1861. He served until January 1863, when a disability forced him to leave. He died in 1920 at about age 82.

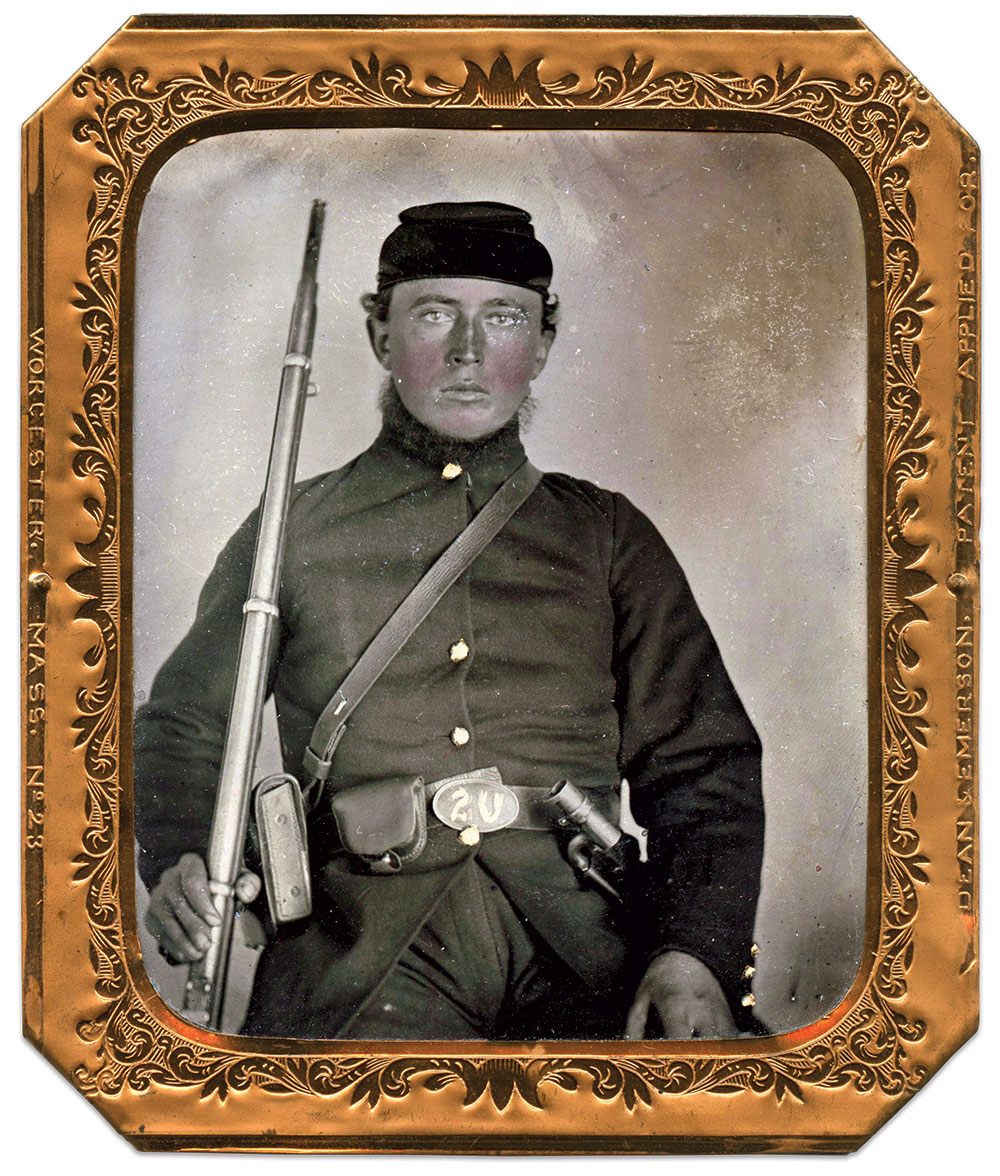

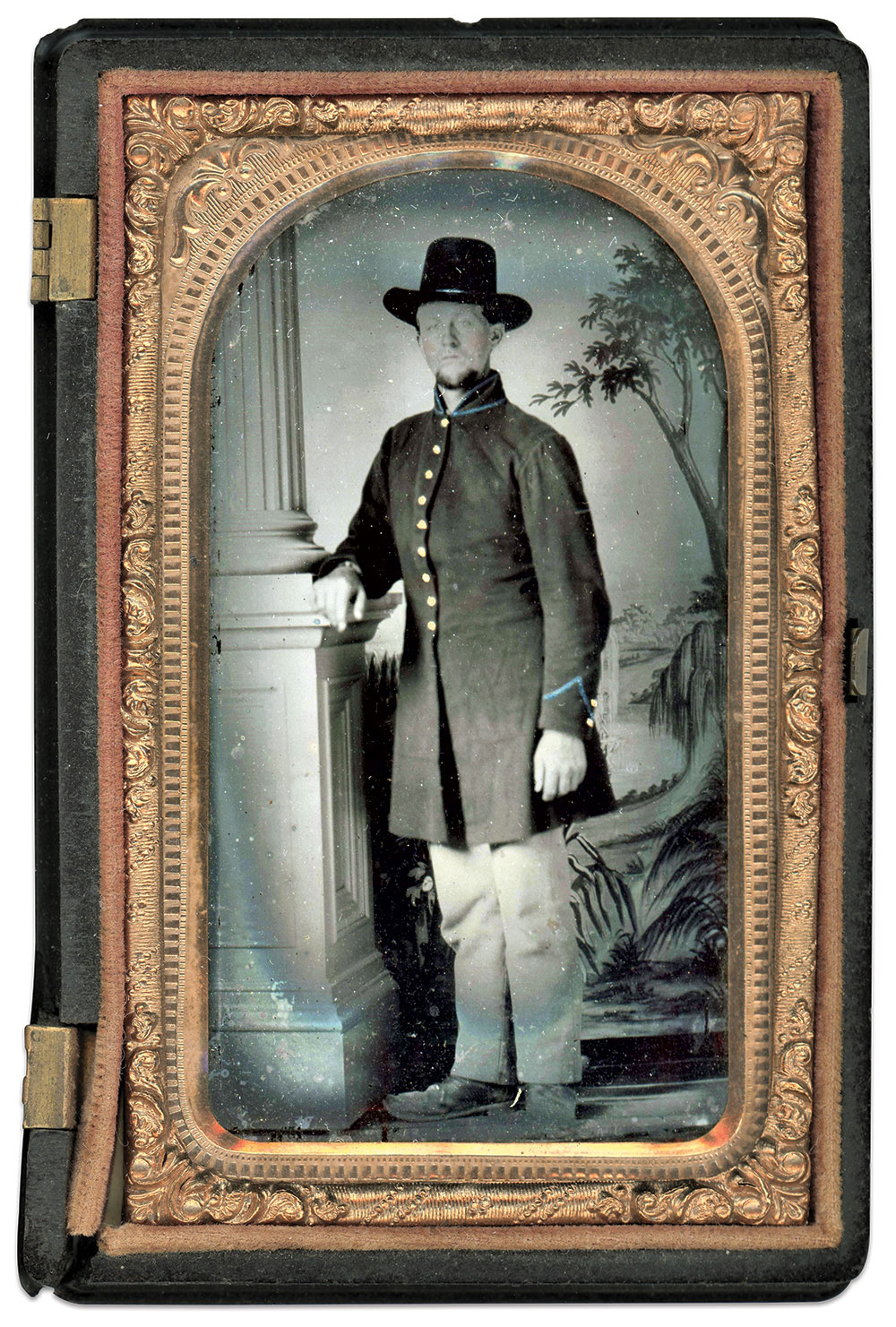

Uncommon Uniform, Temporary Field Alteration

When the war came, Johann Hinrich Augustus Haun, a 21-year-old immigrant from the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, became a soldier for his adopted homeland. “August” joined the 8th Iowa Infantry in the summer of 1861, and is pictured here uniformed in an uncommon 5-button blouse. He also wears his cartridge box mounted on the belt, and a rifle sling used in place of a standard cartridge box strap. This is likely a temporary field alteration to shift the weight of ammunition from his waist to his shoulders. He holds a brightly burnished Enfield. Haun’s service ended less than a year later at Shiloh, where he suffered a mortal wound.

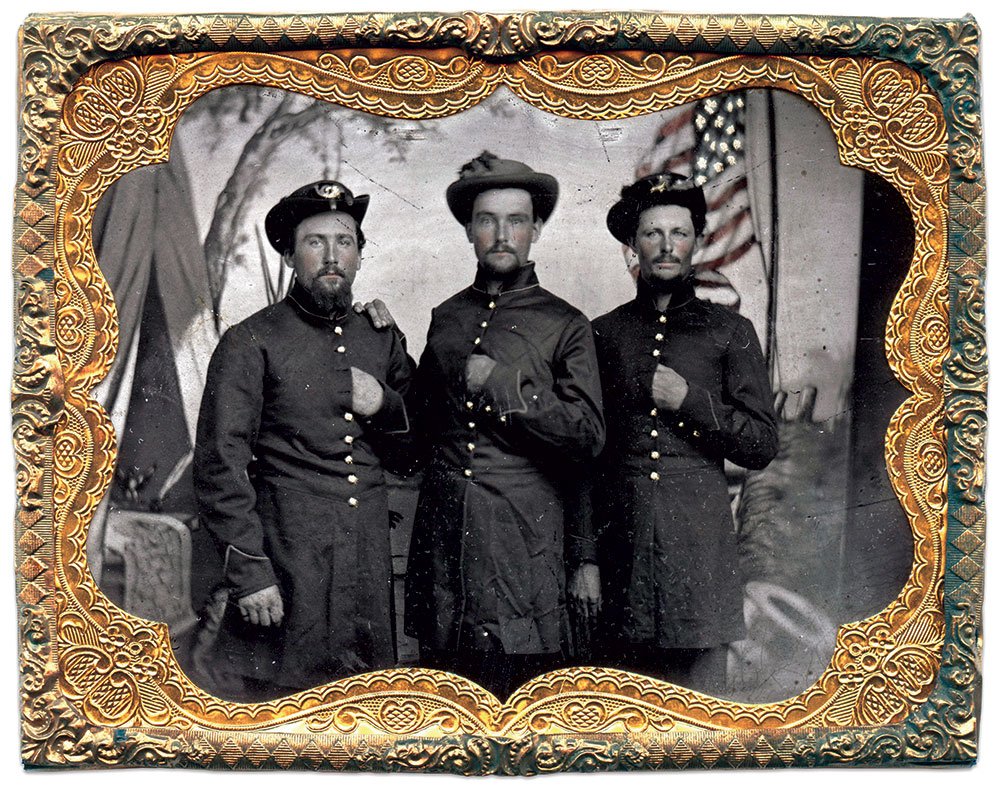

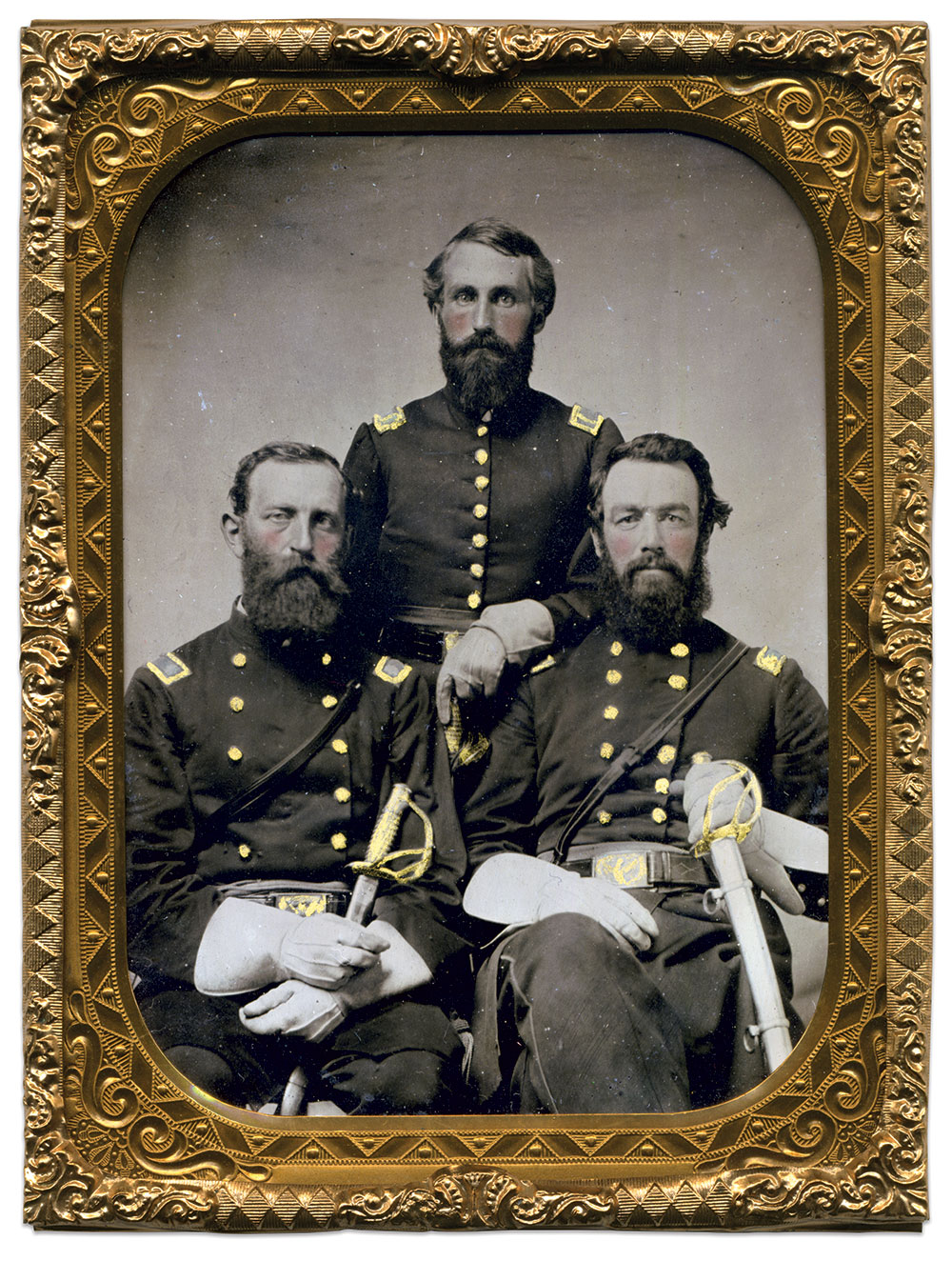

Bonds of Friendship, Family and War

New uniforms presented a reason to get an image made for folks back home. This may have motivated these men in Company C of the 8th Iowa Infantry, who posed for this portrait at Benton Barracks, Mo. From left, they are: Lytle A. Stephens, Martin Luther Orris and Jeremiah Hackathorn Carl, all residents of Ainsworth, Iowa. They shared more soldier experiences than they might have ever foreseen—especially at Shiloh. The 8th became trapped when the Hornet’s Nest collapsed and most of the men surrendered, including Stephens and Carl. Orris numbered among the few who escaped.

The trio survived Shiloh and the rest of the war, and returned home to Ainsworth. Friendship, family and war forever linked all three. Orris married Cordelia Stephens, Lytle’s sister. Orris, a farmer who hailed from Pennsylvania, died first, at age 69 in 1911. Stephens, an Ohio native who farmed and raised stock, passed 10 years later at age 82. Carl, also a Pennsylvanian, went on to become a restauranteur and a justice of the peace. He joined his comrades in 1922. He was 82.

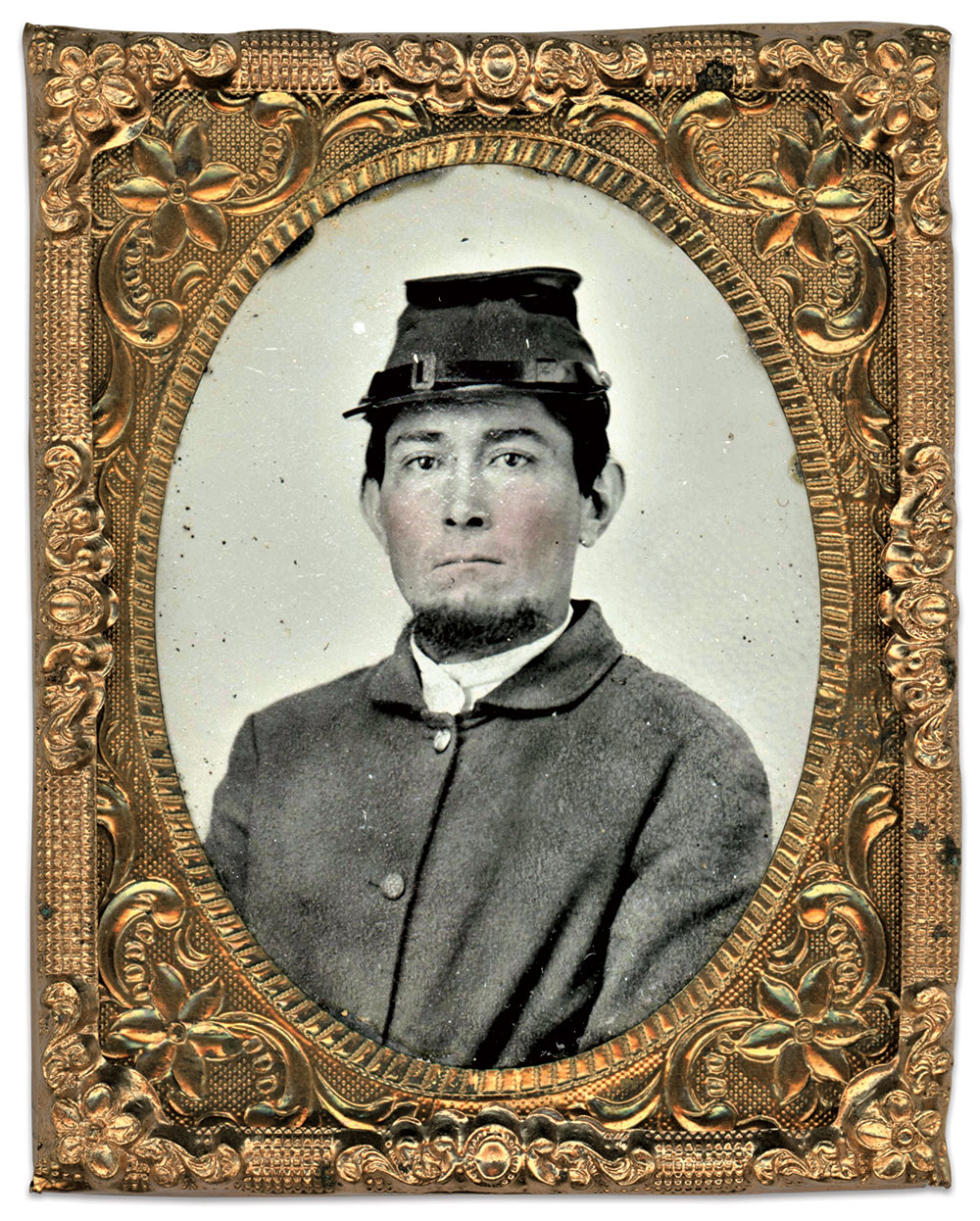

Colonel’s Cook

A regiment, like any military organization in war, is a team. Every role, no matter its function, is important. Jacob A. Rupert, a private in Company C of the 13th Iowa Infantry, played his part as cook to the regiment’s colonel, John Shane.

Rupert, a Pennsylvania native who resided in Mount Vernon, Iowa, enlisted in September 1861. He sits for the camera gripping a large cigar in his mouth, and a star cockade with ribbons sits prominently on his chest. Every aspect of his pose shows a young man feeling his oats, ready to take on the world.

Rupert served through the end of the war, then melted back into society, married twice and fathered nine children. In 1908, on the way home from Phoenix, Ariz., where he had journeyed to recover from poor health, he stopped in Pueblo, Colo. There, he fell ill with ptomaine after eating a tainted can of peas, and succumbed to its effects. He was 65 years old.

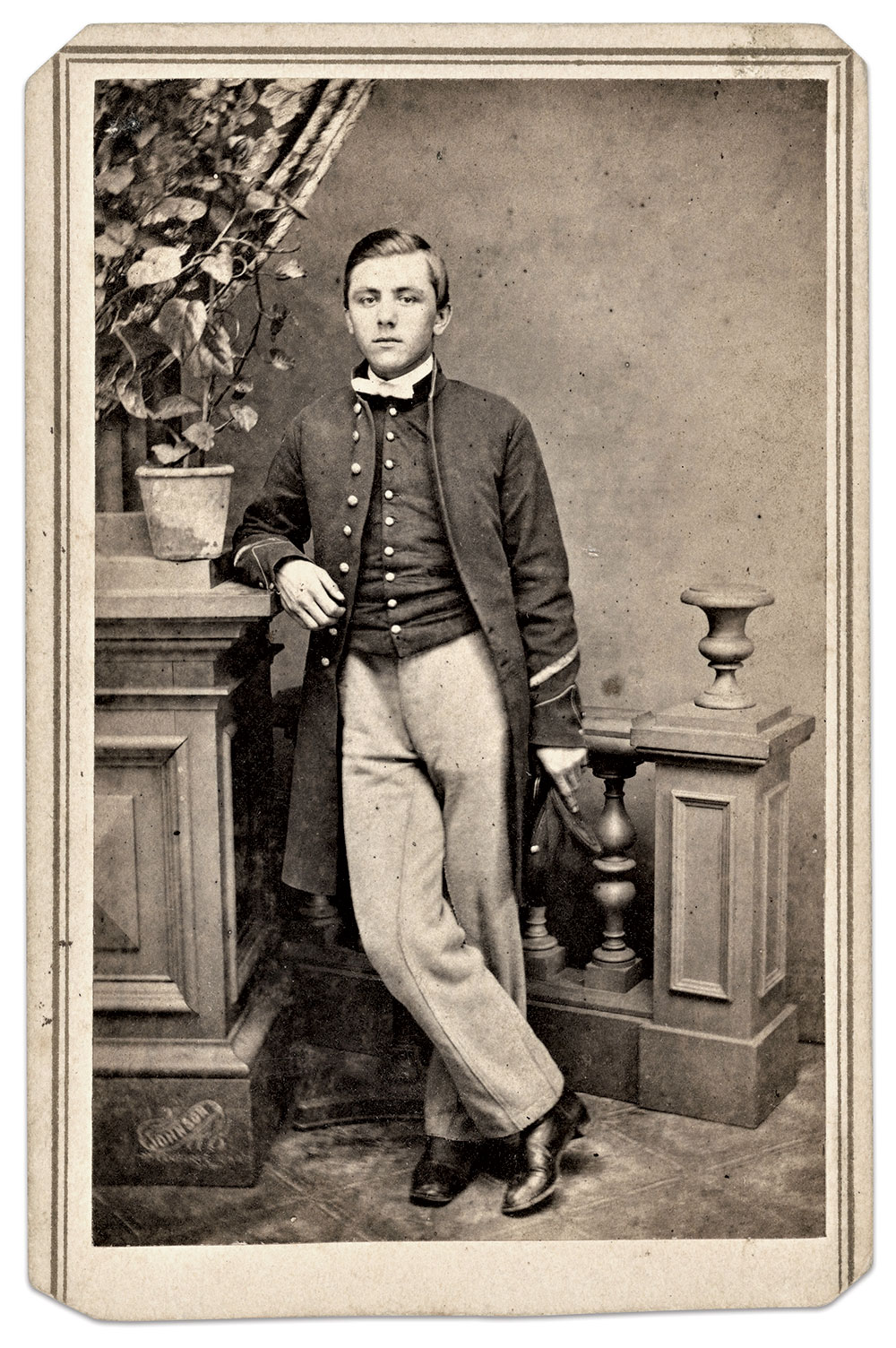

New Uniforms for the Seventh

Conrad Binder Stocker, 41, wears a stylish New York State jacket supplied to him and his comrades in the 7th Iowa Infantry in the fall of 1861, after months of hard service in Kentucky and Missouri. The men referred to them as Zouave Jackets, and it is likely they wore them at Battle of Belmont, Mo., in November 1861. Stocker survived the battle and the war, returning to his Ottumwa farm in 1864. He died in 1889 at age 68.

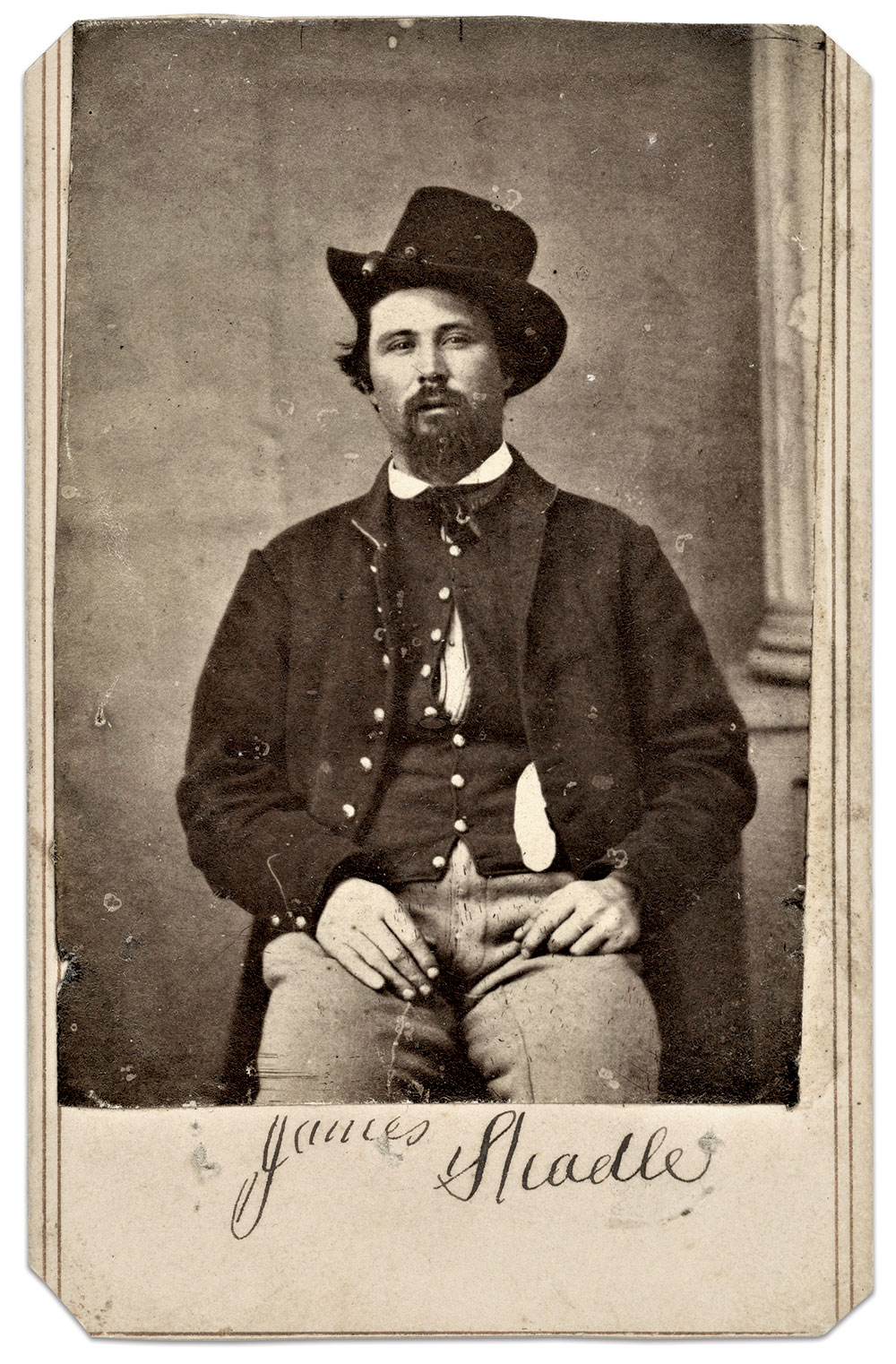

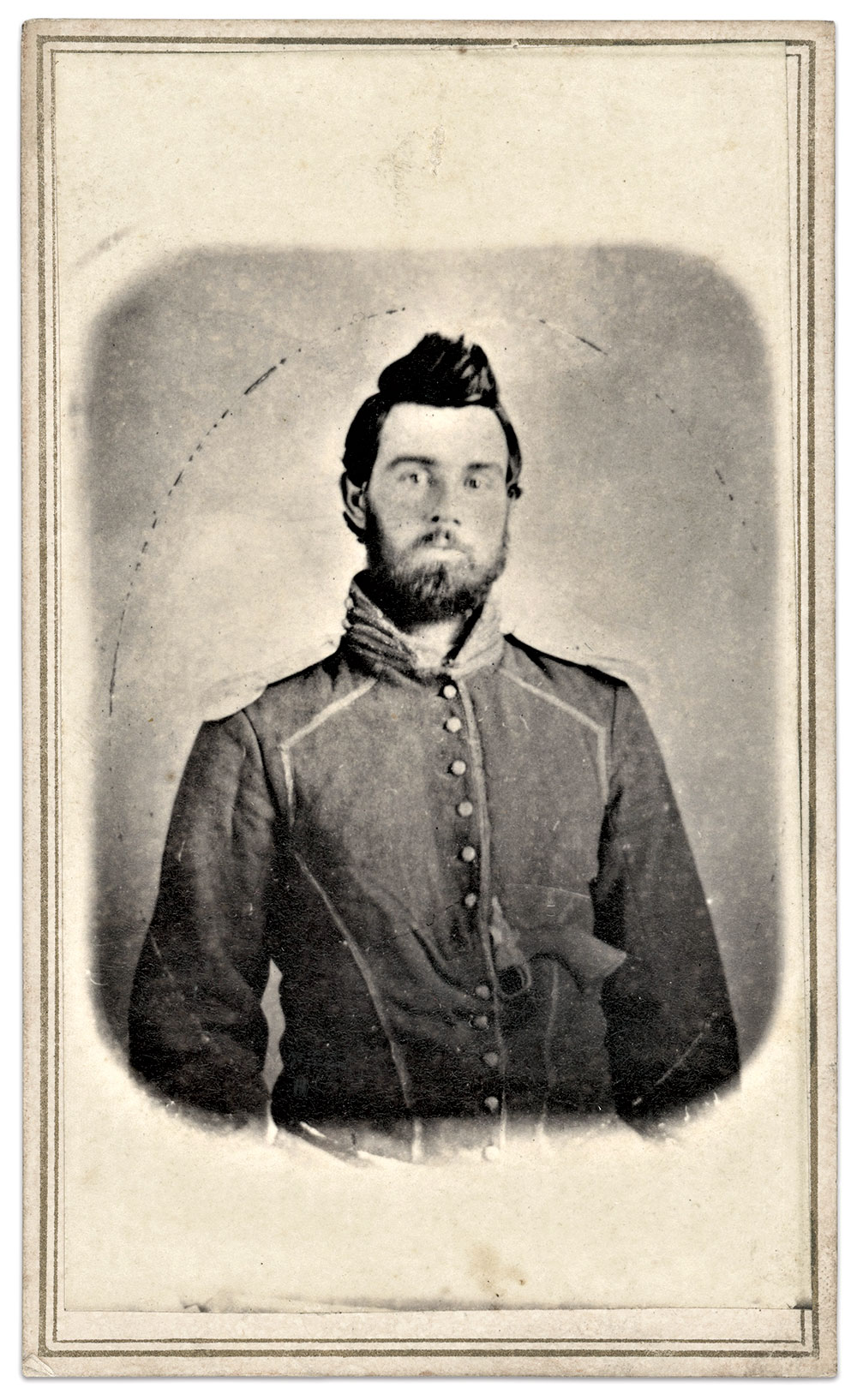

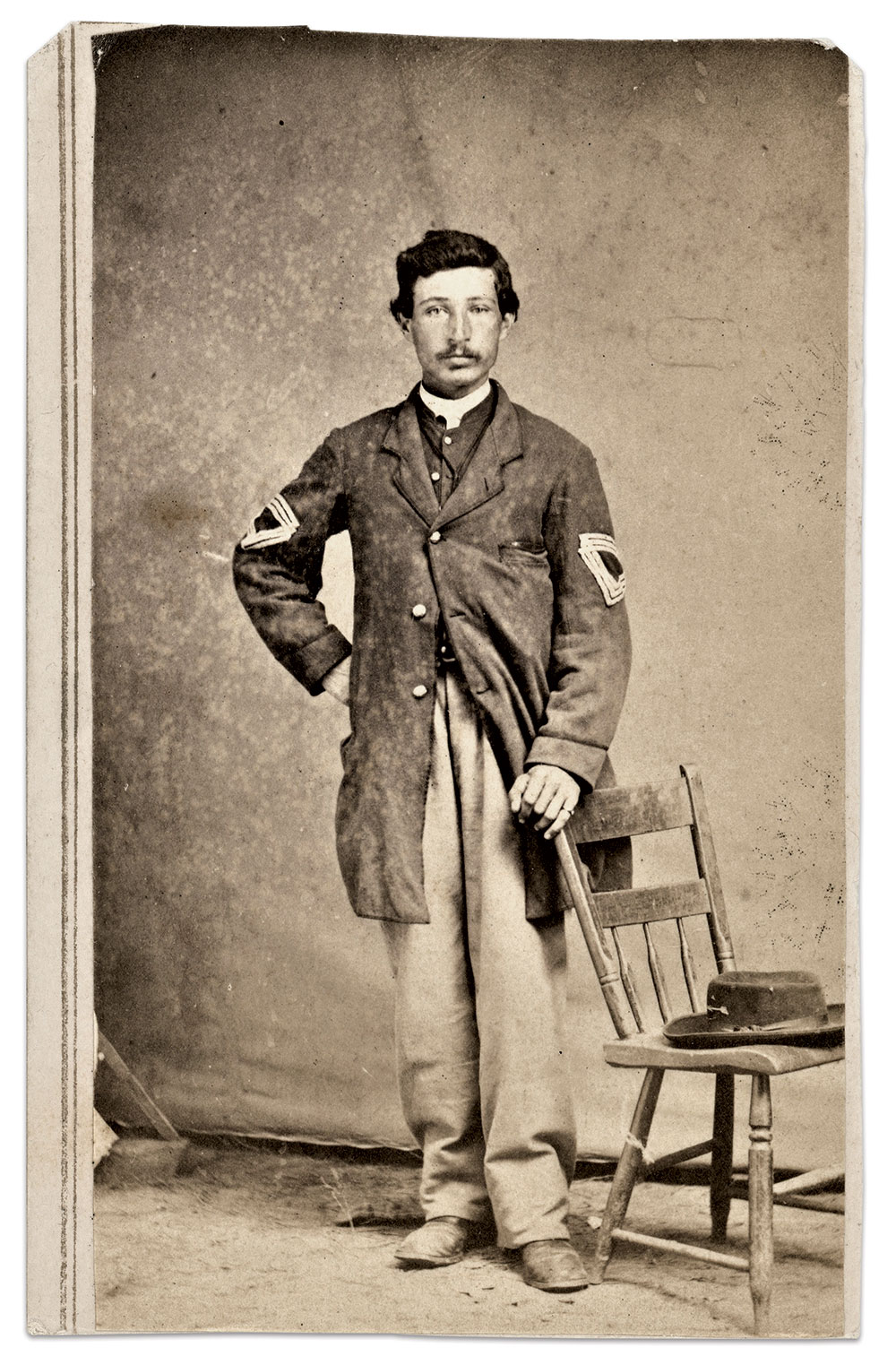

One of the Earliest Volunteers

James William Shadle enlisted in the 2nd Iowa Infantry in 1861—one of the first volunteers who rushed to America’s defense after the war began. Severely wounded in the right shoulder during the 1864 Battle of Atlanta, he recovered and went on to participate in the Carolinas Campaign. He mustered out as a first sergeant with his comrades in July 1865. He died in Jones County, Iowa, in 1899 at age 62.

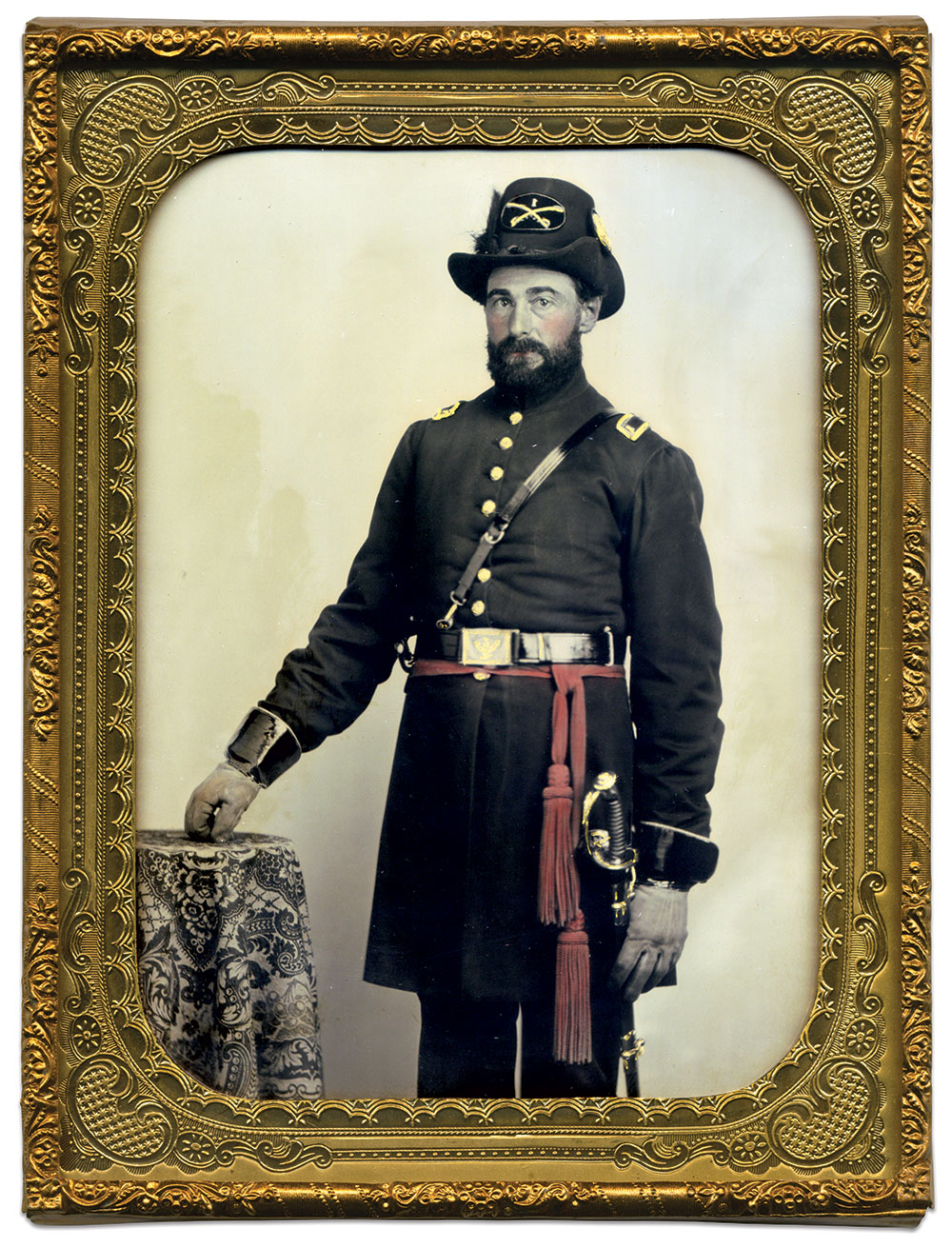

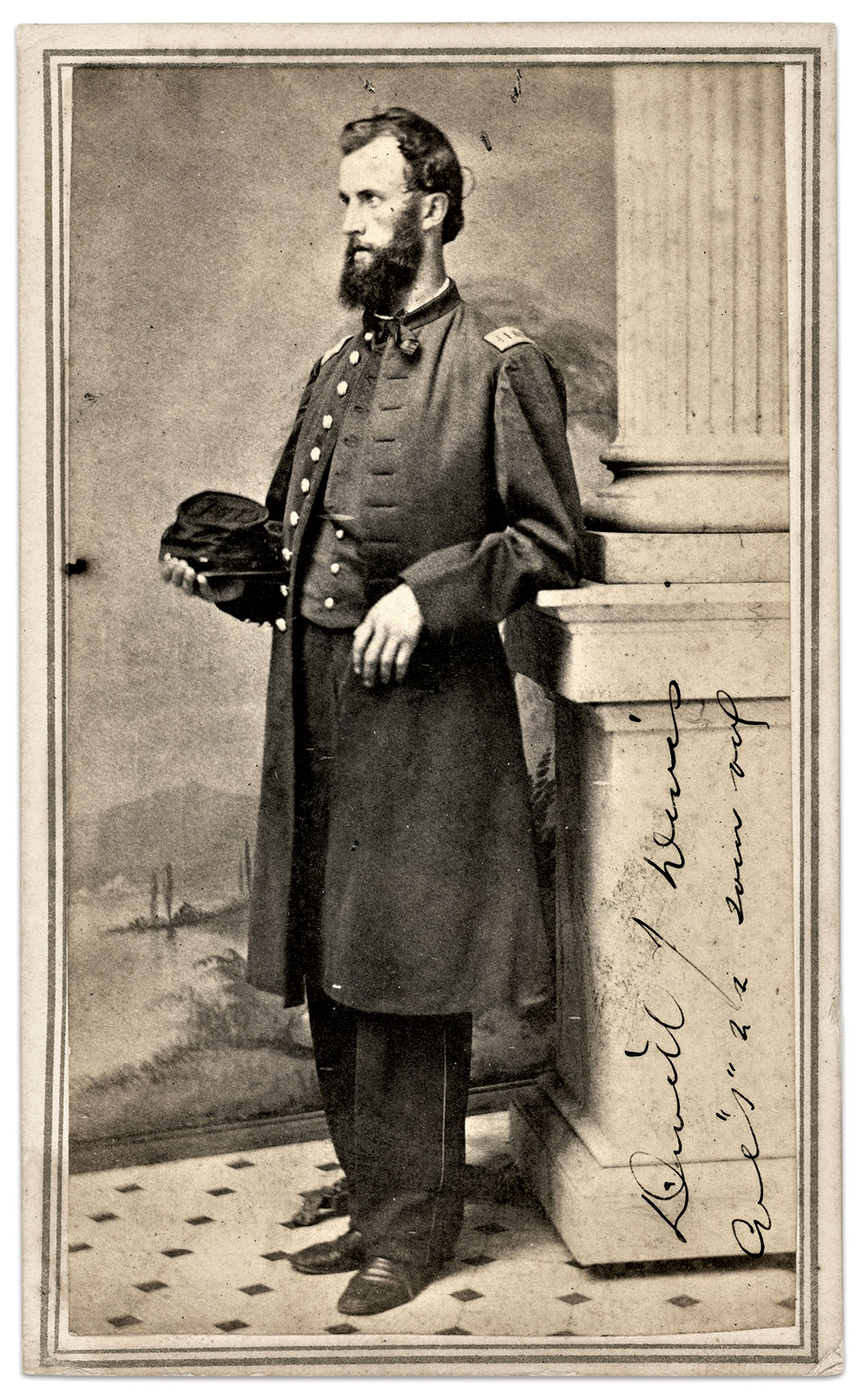

The First Lieutenant of “The Black Plume Rangers”

In the spring of 1861, citizens in Iowa’s Clinton and Jackson counties rushed to organize a cavalry company with a state-inspired name—the “Hawkeye Rangers.” More than enough volunteers enrolled, and the overflow formed a new company. Not to be outdone in name, they branded themselves “The Black Plume Rangers.” Its first lieutenant is pictured here: James E. Crissy, a 40-year-old native New Yorker who clerked in Lyons. Crissy left behind his wife, Laura, and two children, to command the company.

He appears here in uniform with plumed dress hat and stylish gauntlets with close-cropped fur nap cuffs. The Black Plume Rangers became Company M of the 1st Iowa Cavalry. Crissy’s military service lasted only a matter of months. In December 1861 he resigned his commission and returned to his family. They eventually moved to Michigan, where Crissy prospered as a real estate agent in Jackson until his death in 1876 at age 56.

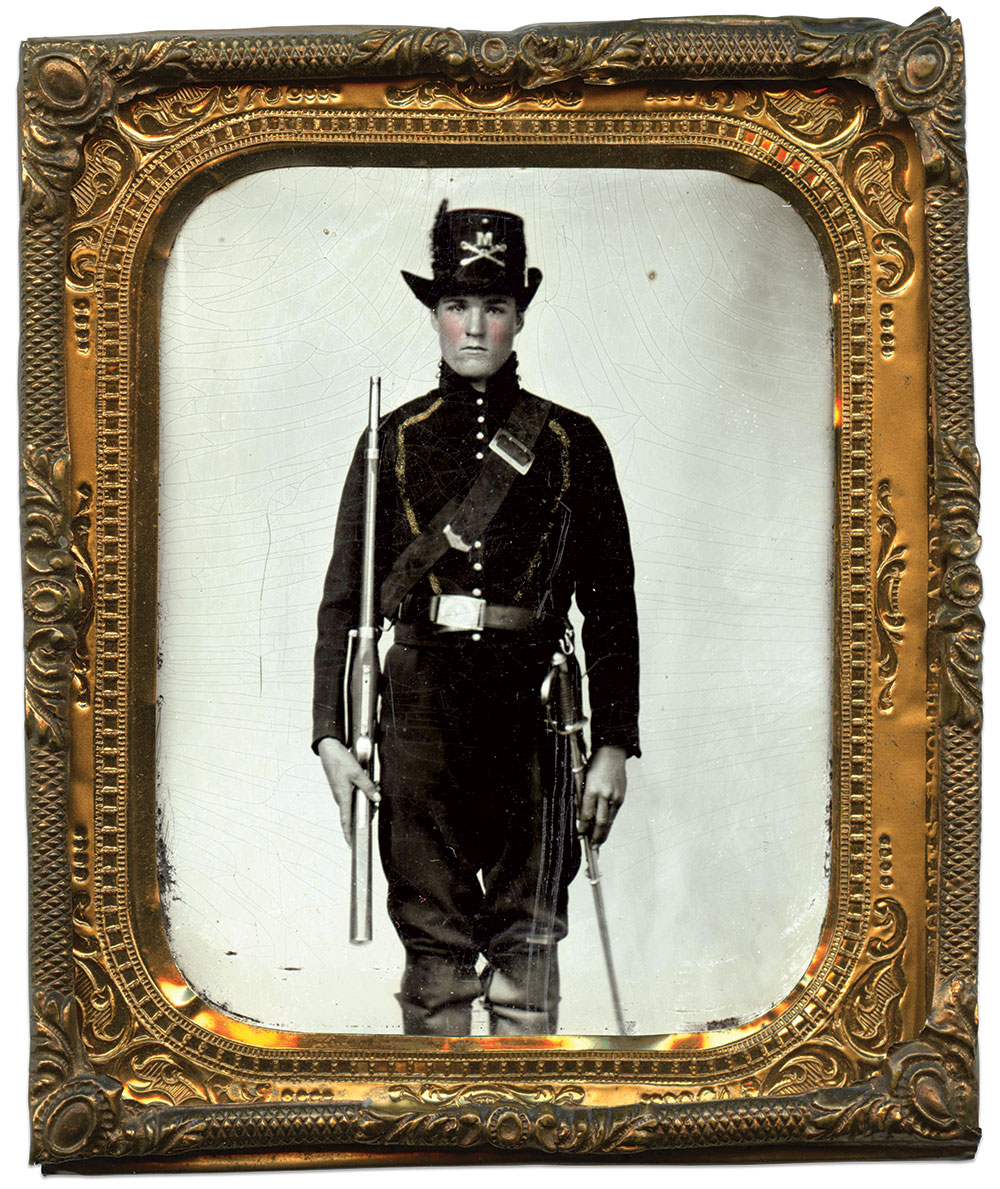

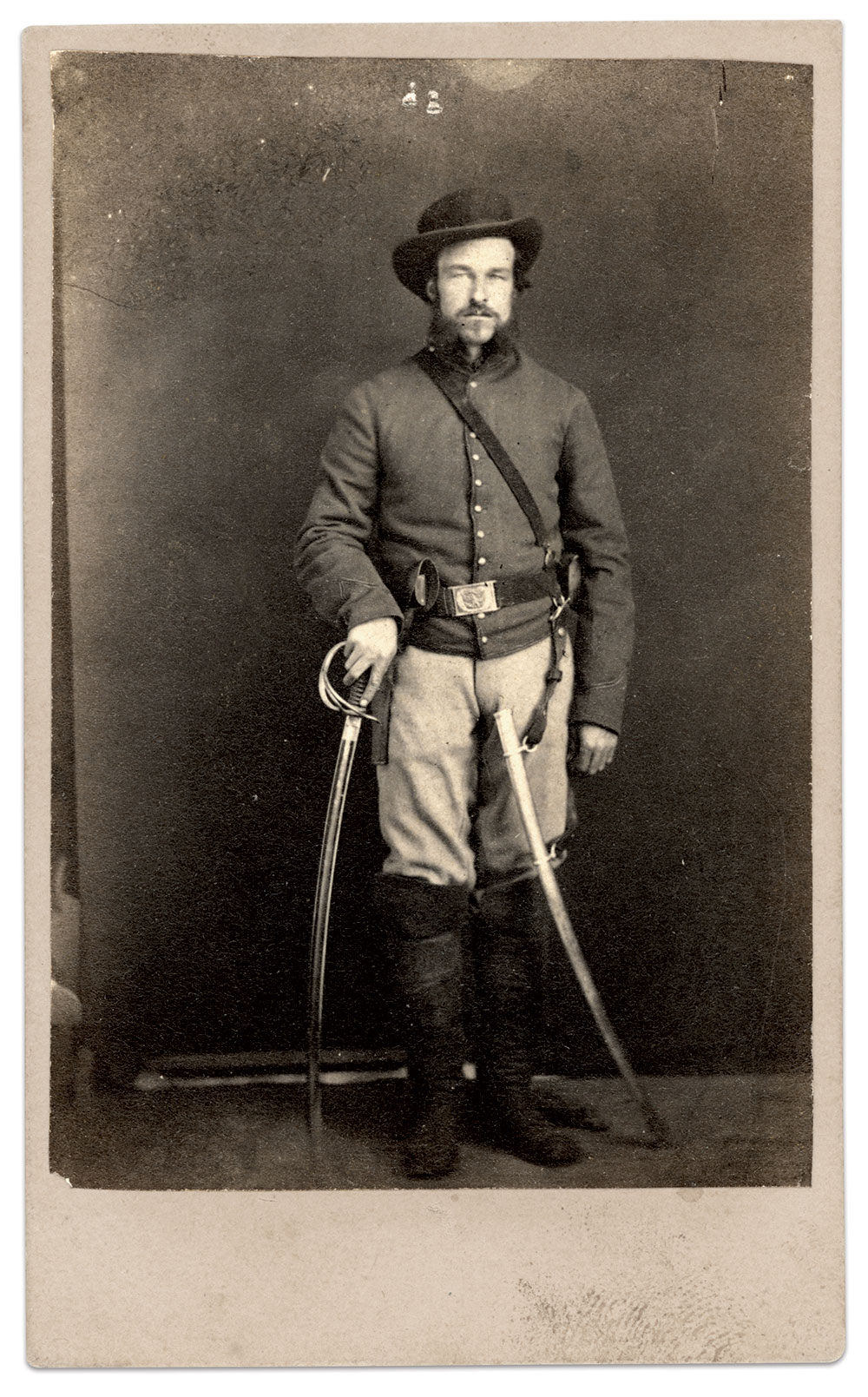

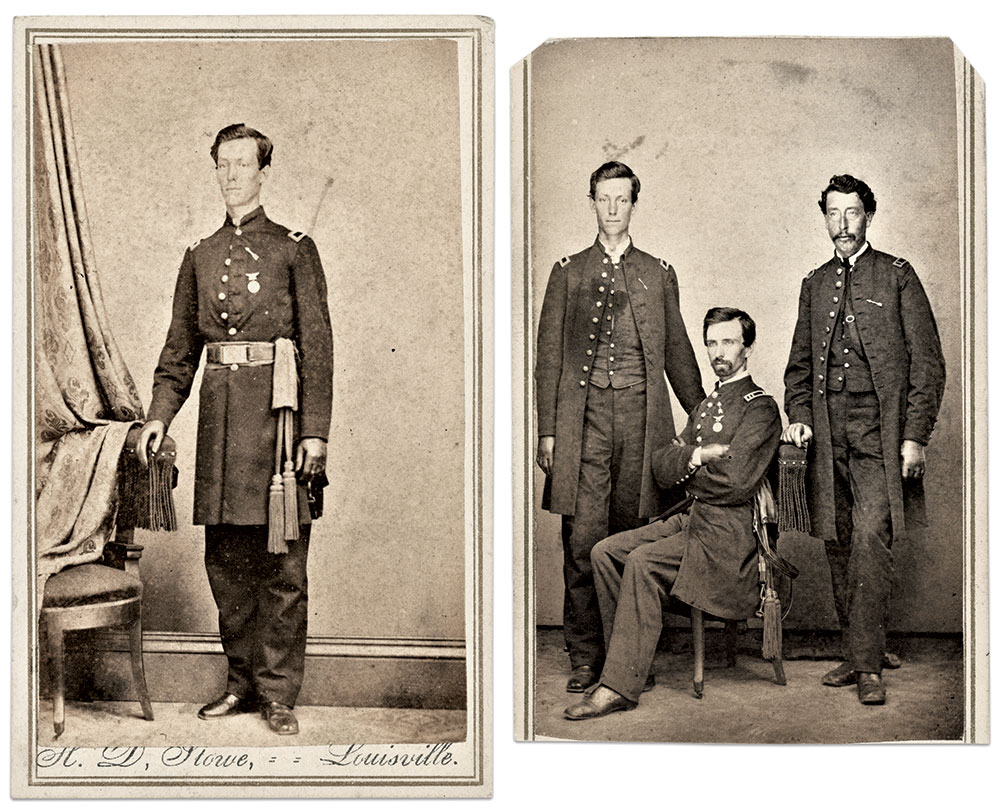

Portraits of a Hawkeye Horseman

John Wesley Blades.joined the 3rd Iowa Cavalry in August 1861. In the rush to arm and equip the men, the state adopted anything it could find. Blades illustrates this, as he wears a distinctive piped shell jacket similar to those worn by the 2nd Missouri Cavalr, also known as Merrill’s Horse. He holds a Model 1843 Hall-North side-lever carbine.

Blades posed for a second portrait later in the war, dressed for field service and sporting a pierced ear and loop earring.

Blades mustered out of the regiment with surviving comrades at Atlanta. He lived until 1922, dying at age 78 in Florence, Colo.

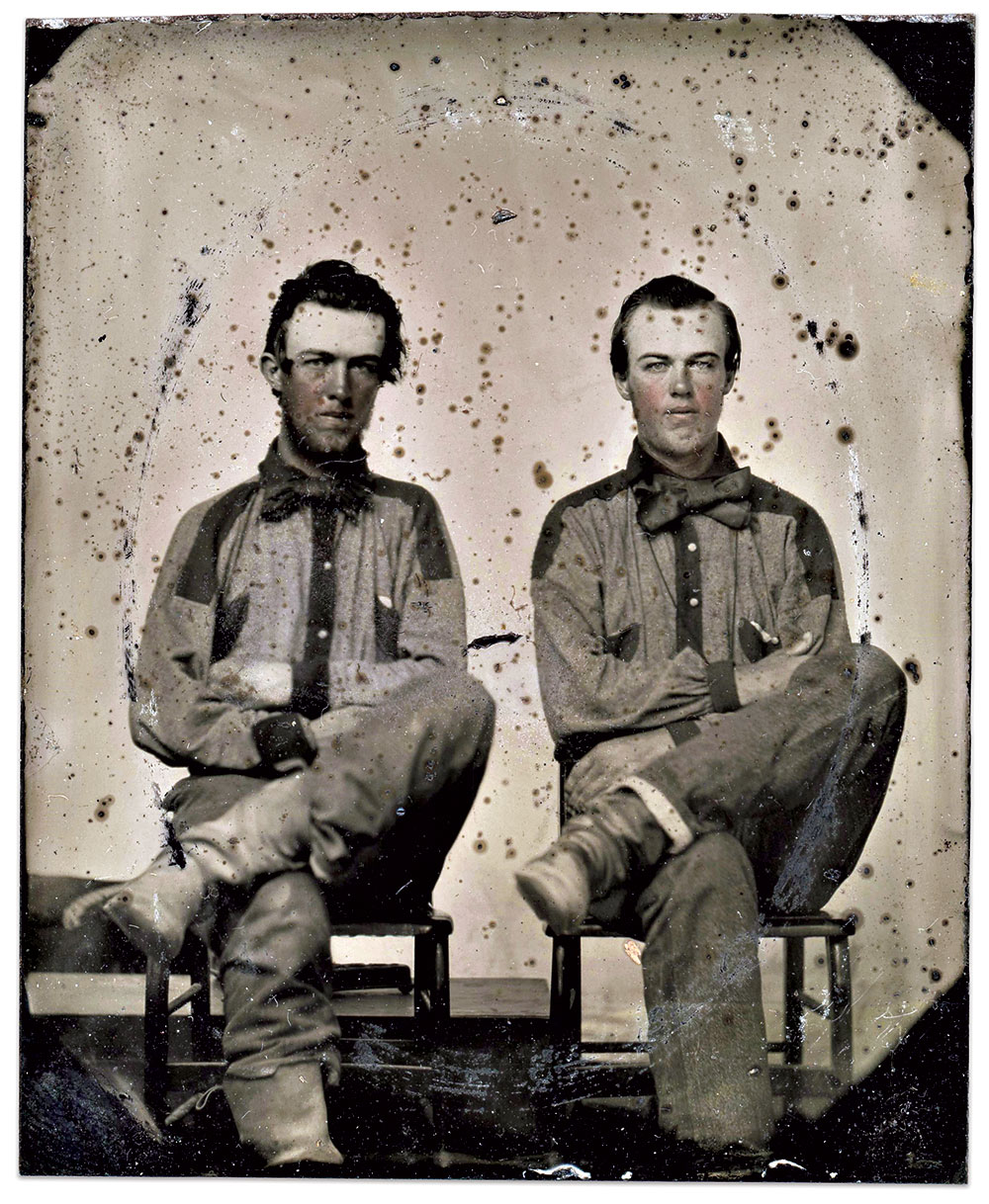

Prairie Fighters

Settlers in sparsely populated western Iowa volunteered with the same enthusiasm as men in the Mississippi River towns. They included brothers George W. Ramsey Jr., seated left, and older brother Miles Kennedy Ramsey. Ohio-born residents in Boonesborough, they enlisted in Company E of the 3rd Iowa Infantry in June 1861 and posed for this portrait in Keokuk. Their unconventional blouses illustrate how the state procured any cloth available to make uniforms early on.

The regiment received their first uniforms on July 5, 1861. A member of Company F described them as “pants and a dress coat of fine and substantial gray cloth, trimmed with blue. The pants had the blue cord down the outer seams.” The men took pride in finally getting “a complete uniform, unsurpassed, it was said, by that of any regiment in the service.”

The Ramseys ended their service in 1864 as noncommissioned officers. George became a corporal on April 6, 1862, no doubt related to Shiloh, and made sergeant a year later. Miles earned his corporal’s stripes in 1863. The brothers returned to Boonesborough. Miles died in 1904 at age 64. George lived until 1921, dying at age 80. They are buried in Linwood Park Cemetery in Boone.

1862

Injured at Pea Ridge

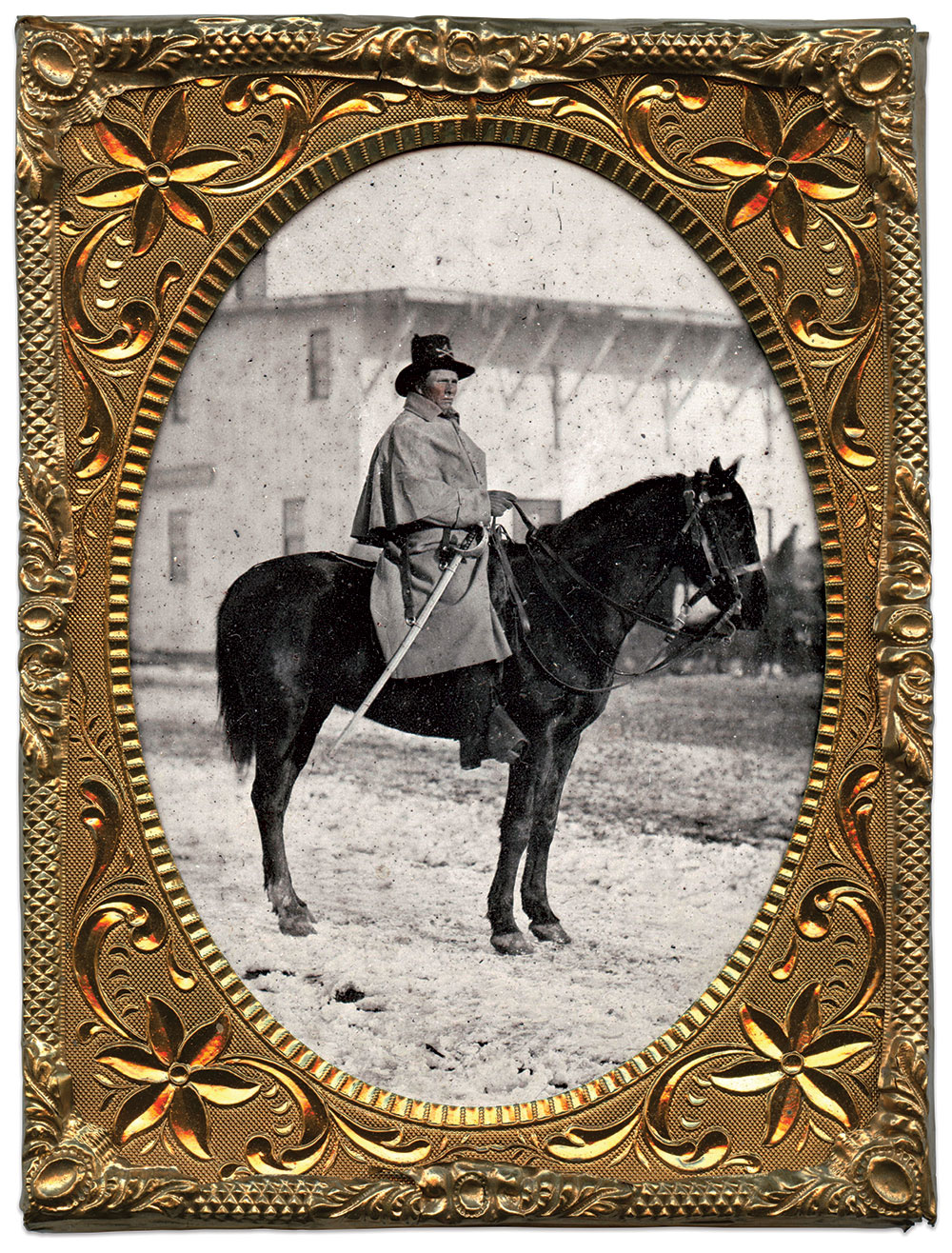

Trooper William James Wishard of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry posed with saber drawn and Colt Dragoon revolver tucked into his waist belt against a painted background well known to collectors as the “Fort on the Hill.” Photographer Ansel R. Butts of St. Louis used the backdrop, and Kentucky-born Wishard numbered among the many soldiers stationed at Benton Barracks who wandered over to Butts’ studio to have his likeness made in the fall of 1861. Later that year or early the next, Wishard posed again, this time wearing his winter overcoat and seated on his horse. By this time Wishard ranked as a commissary sergeant.

Wishard suffered an injury when his horse—perhaps the same picture here—jumped a fence during the March 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark. Wishard left the regiment later in the year and barely outlived the war, dying in 1866 at age 44.

He Made the Ultimate Sacrifice at Iuka

The 5th Iowa Infantry proved its mettle at Iuka, Miss., on Sept. 19, 1862. The Iowans paid a heavy price, suffering more than 220 wounded and killed of 482 engaged—a 46 percent loss. They included the soldier pictured here: Leroy F. Shelley. Born in North Carolina, he married and started a family in Indiana before settling in Jasper County, Iowa, by 1860. The following year, at age 36, he joined the ranks of the 5th.

Exactly where and when he fell at Iuka is lost in time. His remains, along with those of his dead comrades, were buried in a trench on the battlefield. In 1866, the bodies were removed and reinterred at Corinth National Cemetery. Without proper identification, the majority of the remains, including Shelley’s, lay forever with the word “Unknown” etched in stone. His wife, Tabitha, and a daughter, Lucy, survived.

Unexpected Family Reunion

The assistant surgeon of the 8th Iowa Infantry, Augustus W. Hoffmeister, treated many Shiloh casualties. Among the more serious cases was that of a Confederate sergeant who had suffered gunshots in the lung and hand—his younger brother, Heinrich.

The pair had immigrated from their village in the Harz Mountains of Hanover, Germany. Arriving in New York City in 1848, they made their way by water to New Orleans, and went separate ways. Heinrich stayed, changed his name to Herman, and when the war came joined the 1st Louisiana Infantry. Augustus journeyed to St. Louis, studied chemistry and medicine, and settled in Fort Madison, Iowa. He joined the 8th in February 1862, only weeks before Shiloh.

Augustus’ treatment of his wounded brother was successful. Herman lost three fingers on his right hand and, after being released received a medical discharge. He remained in Louisiana and died in 1899. Augustus advanced to full surgeon of the 8th and remained on duty until he resigned in 1864. He returned to Fort Madison, where, in 1866, he became surgeon of the city’s penitentiary. He died in 1896 at age 68, survived by a large family.

Augustus and Herman went to their graves never speaking to each other following their unexpected reunion at Shiloh.

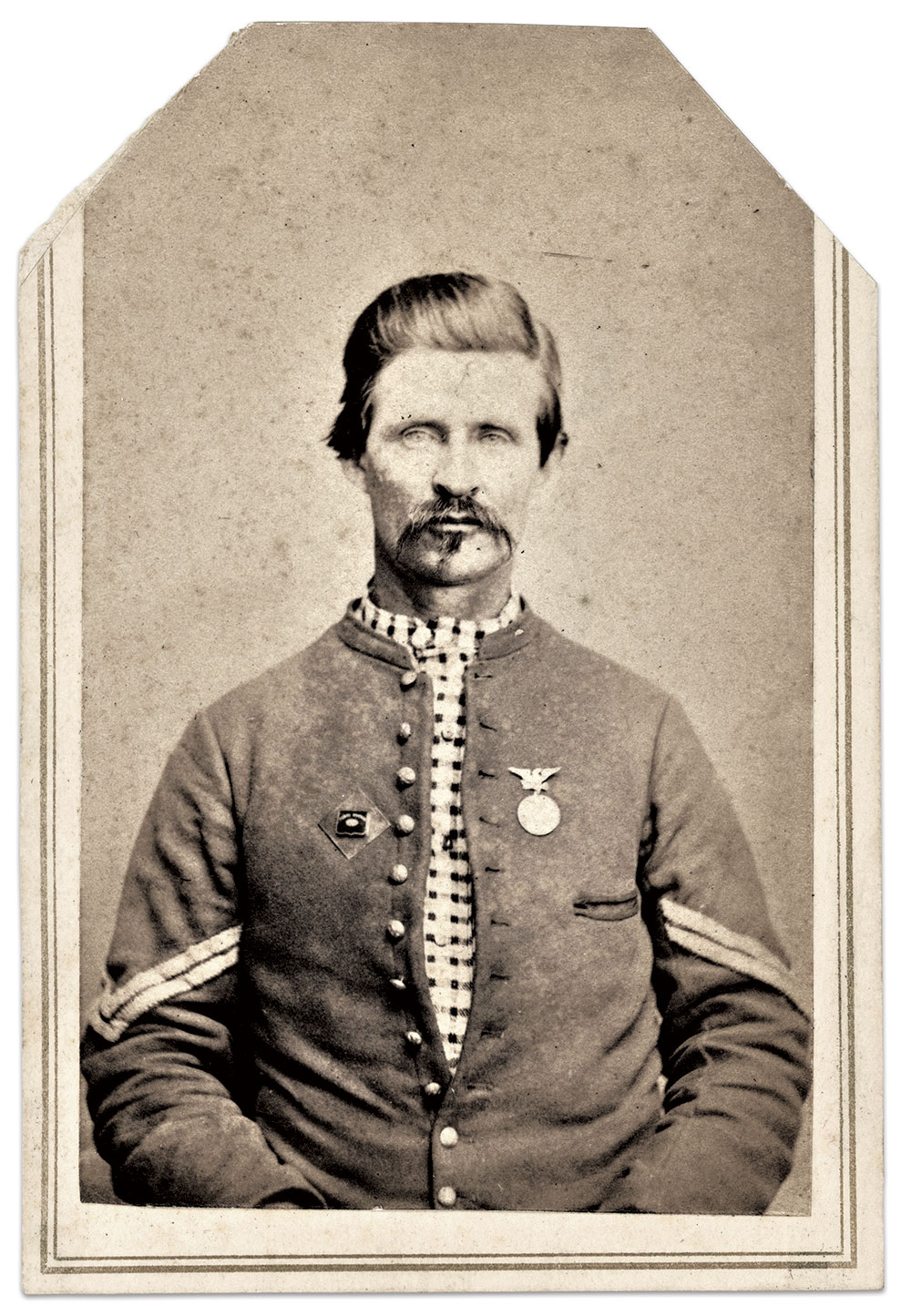

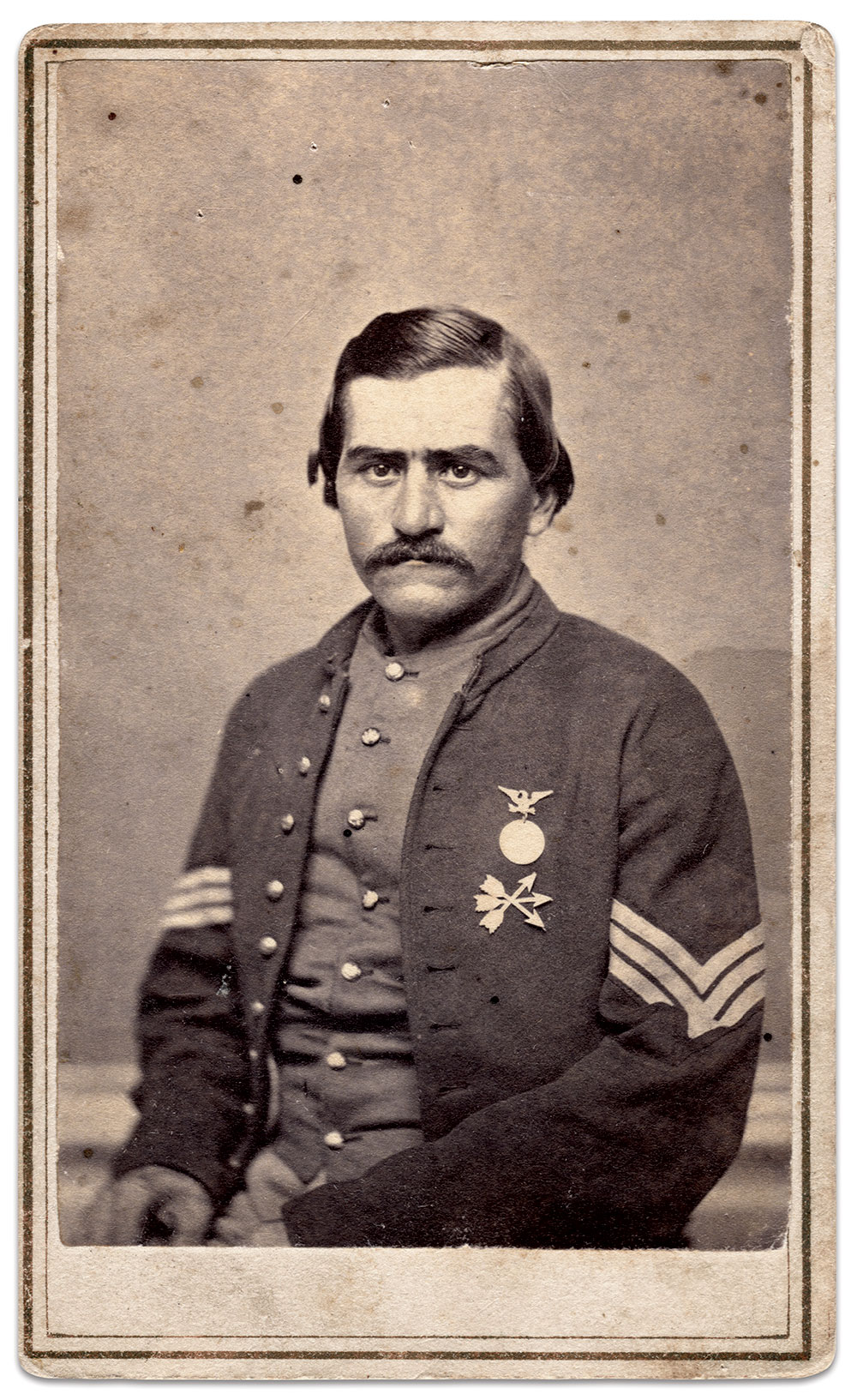

With the Valorous 4th at Pea Ridge

At the Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., in March 1862, the 4th Iowa Infantry received high praise for its valor. Honor came at a price: About half of the Iowans engaged landed on the casualty list, including Elisha C. Stewart. A New York-born joiner, he suffered a hand wound. He recovered and went on to fight in the Vicksburg Campaign and other Western Theater actions. He is pictured here as a corporal in July 1865, wearing his 15th Corps badge and an Army of Georgia medal. He died in 1896 at about age 63. His remains rest at a local cemetery in Richfield, Kan.

Son of Scotland at Shiloh

William McDonald of the 14th Iowa Infantry, left, is bundled up in his state issue overcoat with an unidentified pard. They likely posed soon after their enlistment in November 1861 while at Camp McClellan in the Mississippi River town of Davenport, Iowa. McDonald, a Scottish immigrant, had labored on a farm about 60 miles southeast in the Jones County township of Madison.

McDonald proved a reliable infantryman during his almost four years in the army. He rose to corporal, and fell into enemy hands with many in the 14th at Shiloh’s Hornet’s Nest. He survived the war, but did not enjoy peace for long. He died in Jones County in 1877 at age 41. His remains rest in a cemetery in Scotch Grove.

The Linkins Go to War

On the Linkins farm in New London, all three boys in the family joined the army in 1861 and 1862. The eldest, 25-year-old Emanuel, returned home to his native Ohio, joined the Buckeye State’s 77th Infantry, and died at Shiloh. His younger brothers, William Christopher Columbus and George Washington Jr., joined Iowa infantry regiments and survived. William served in the 11th, which fought at Shiloh and the Atlanta and Carolina campaigns. He died in 1918 at age 79. George Jr. enlisted in the 25th, which participated in the relief of Chattanooga, and the Atlanta and Carolina campaigns. He lived until 1917, dying at about age 72.

Skeleton Walking

Shiloh’s Hornet’s Nest resulted in a massive number of casualties among Iowa boys, including James Melvin Tarpenning of the state’s 12th Infantry. Shot above the knee and captured, Confederates sent the 21-year-old Ohio native and about 400 of his comrades off to prisoner of war camps. Over the next eight months, Tarpenning battled gangrene and chronic diarrhea. When finally paroled at Annapolis, Md., one source described Tarpenning as a walking skeleton, a shadow of his former self. He received a medical discharge in December and went home to recuperate. Down but not out, Tarpenning rejoined the army six months later as a corporal in the 47th Iowa Infantry, a new regiment raised for a 100-day enlistment to release combat troops from rear echelon duty.

Tarpenning finished his service and lived a long life, dying in 1923 at age 82. His wife, Narcissa, and two children survived him.

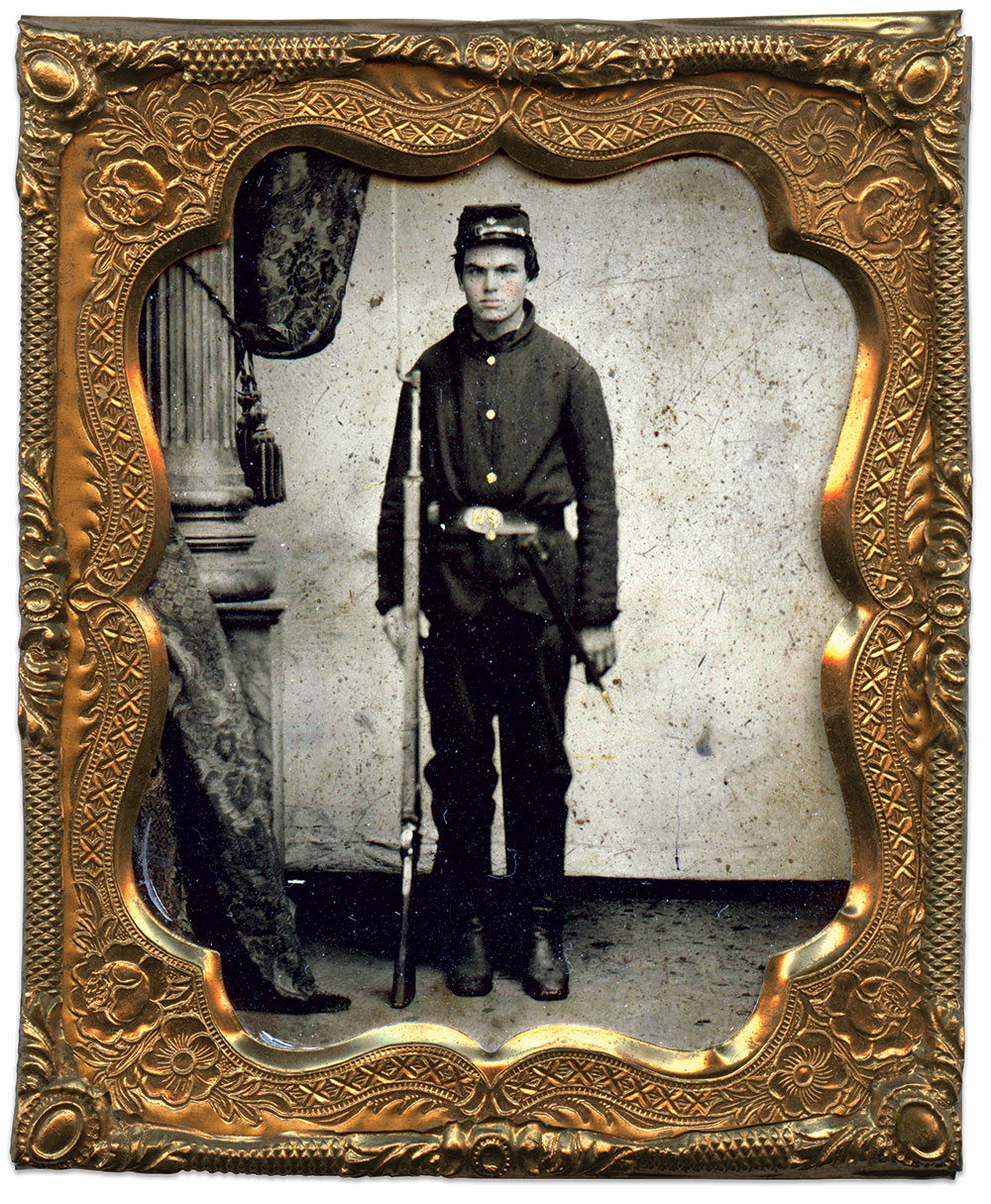

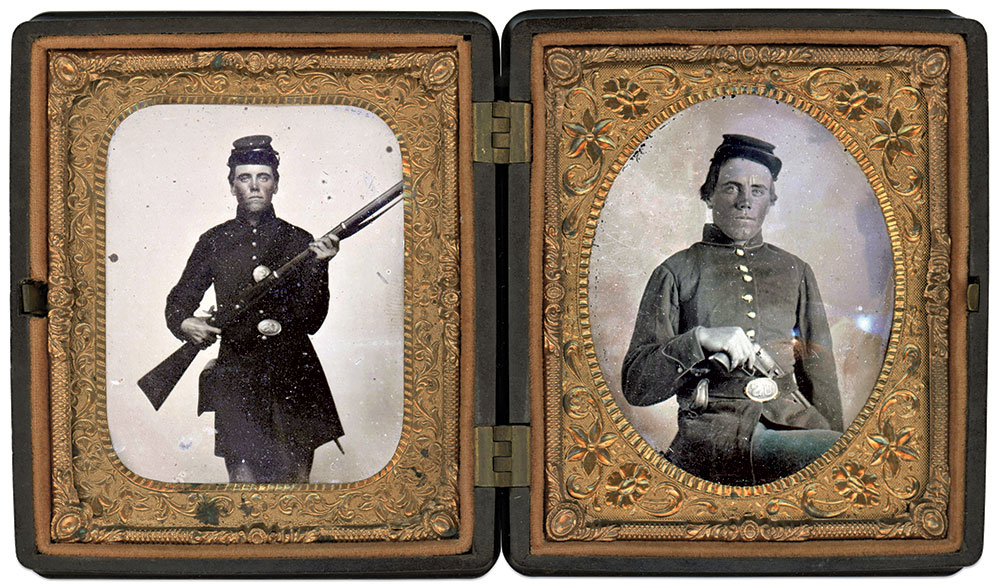

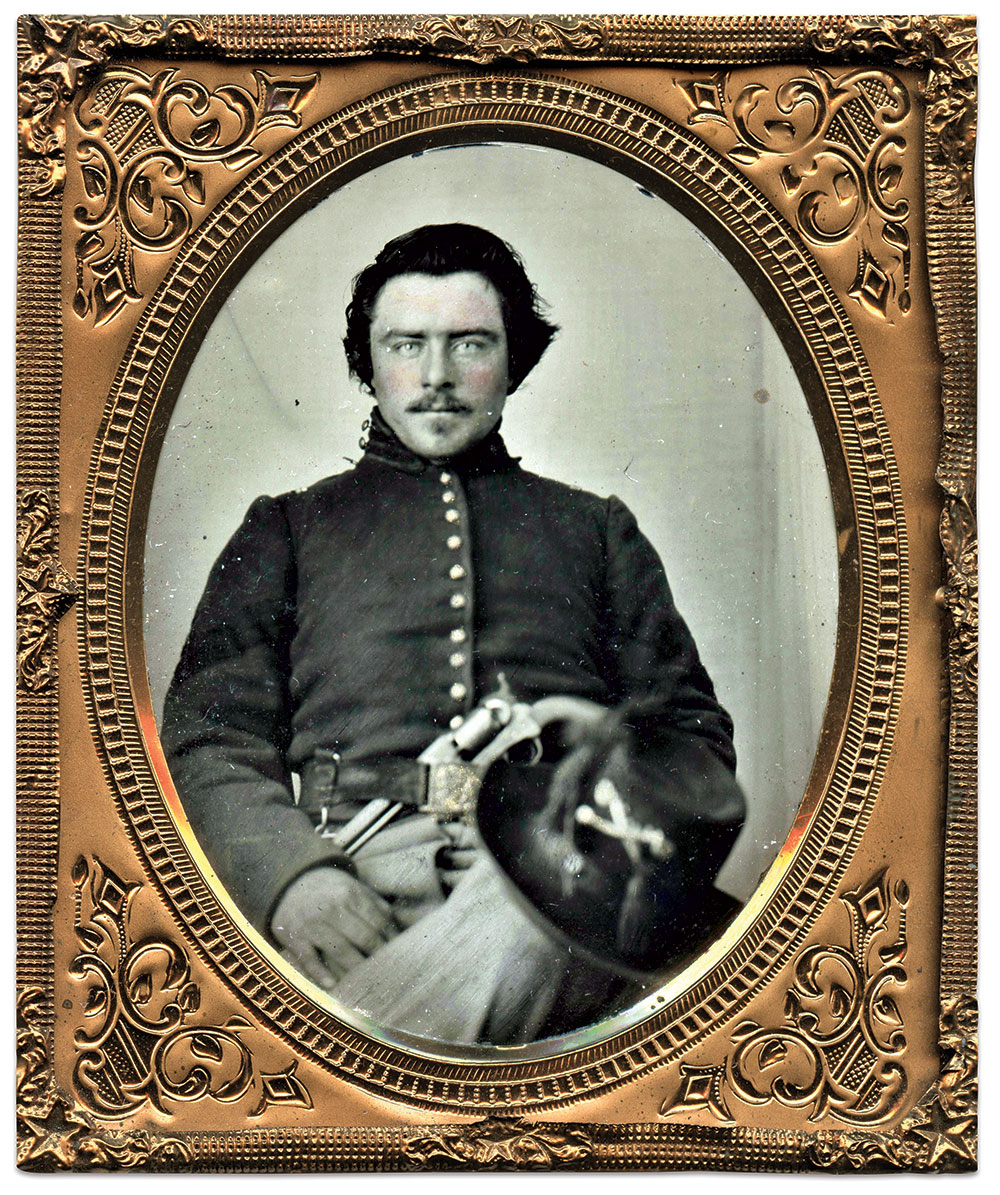

A Mother’s Love

Margaret Morton refused to allow her son, John Wesley, to enlist. But “JW” begged and pleaded with her to let him join the army, seeking the grand adventure. She finally relented, and, in August 1862, he left the family farm in Washington, Iowa, and enlisted in Company C of the 19th Iowa Infantry. He’s pictured, left, with a First Model Colt Dragoon Revolver, and, right, with a musket.

Three months later, Morton found himself deployed as a skirmisher in a cornfield at Prairie Grove, Ark. The assignment may have saved his life, as the rest of the 19th marched into a storm of shot and shell that caused many casualties in minutes. The 19th went on to serve along the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico coast before it mustered out at Mobile, Ala., in 1865.

Following his service, Morton became the glue that held the veterans of Company C together. In the 1880s, he created a mammoth composite of portraits of survivors of the company. His effort ensured that the names and faces of those with whom he served were recorded for posterity.

Morton passed away at age 84 in 1926.

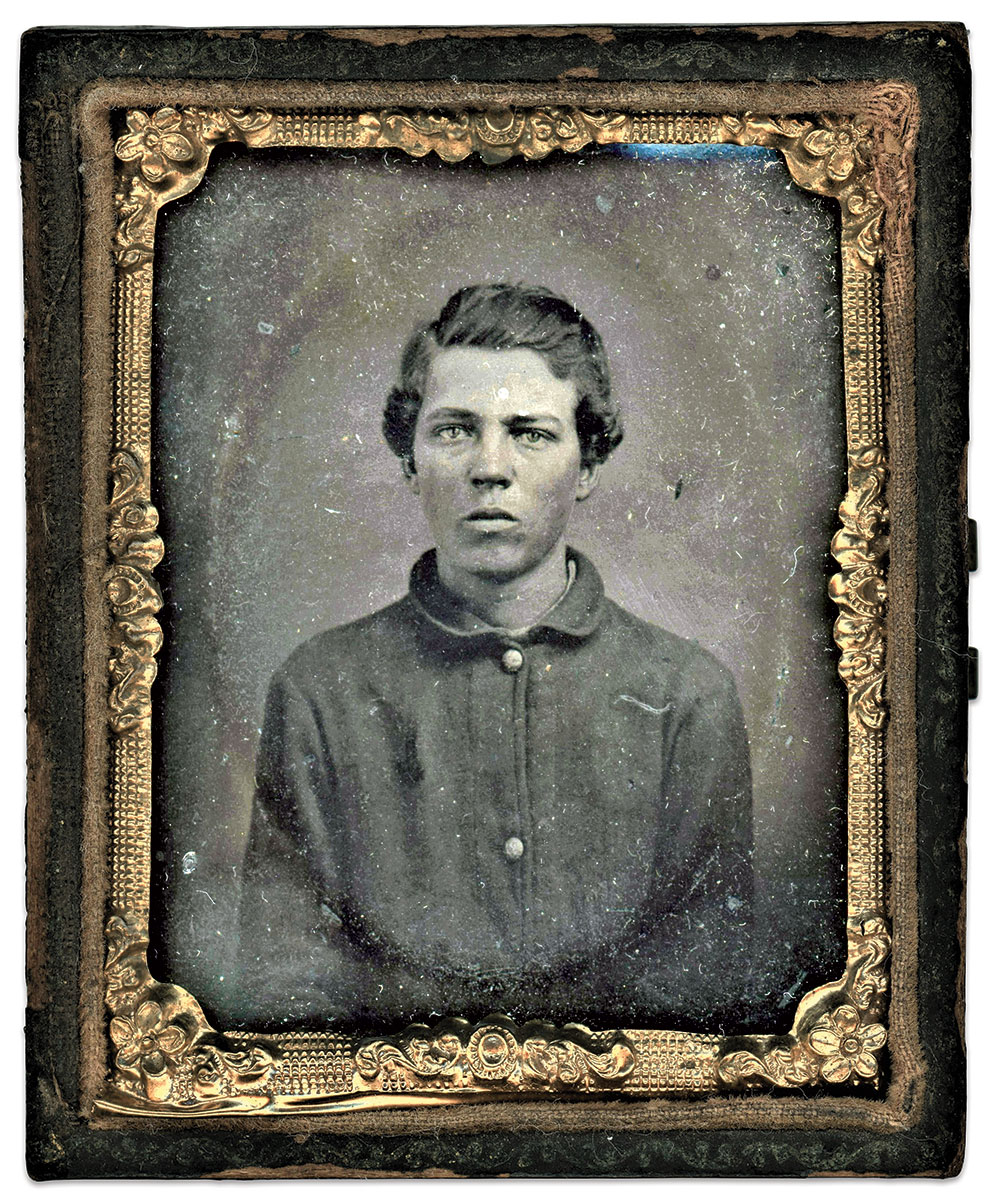

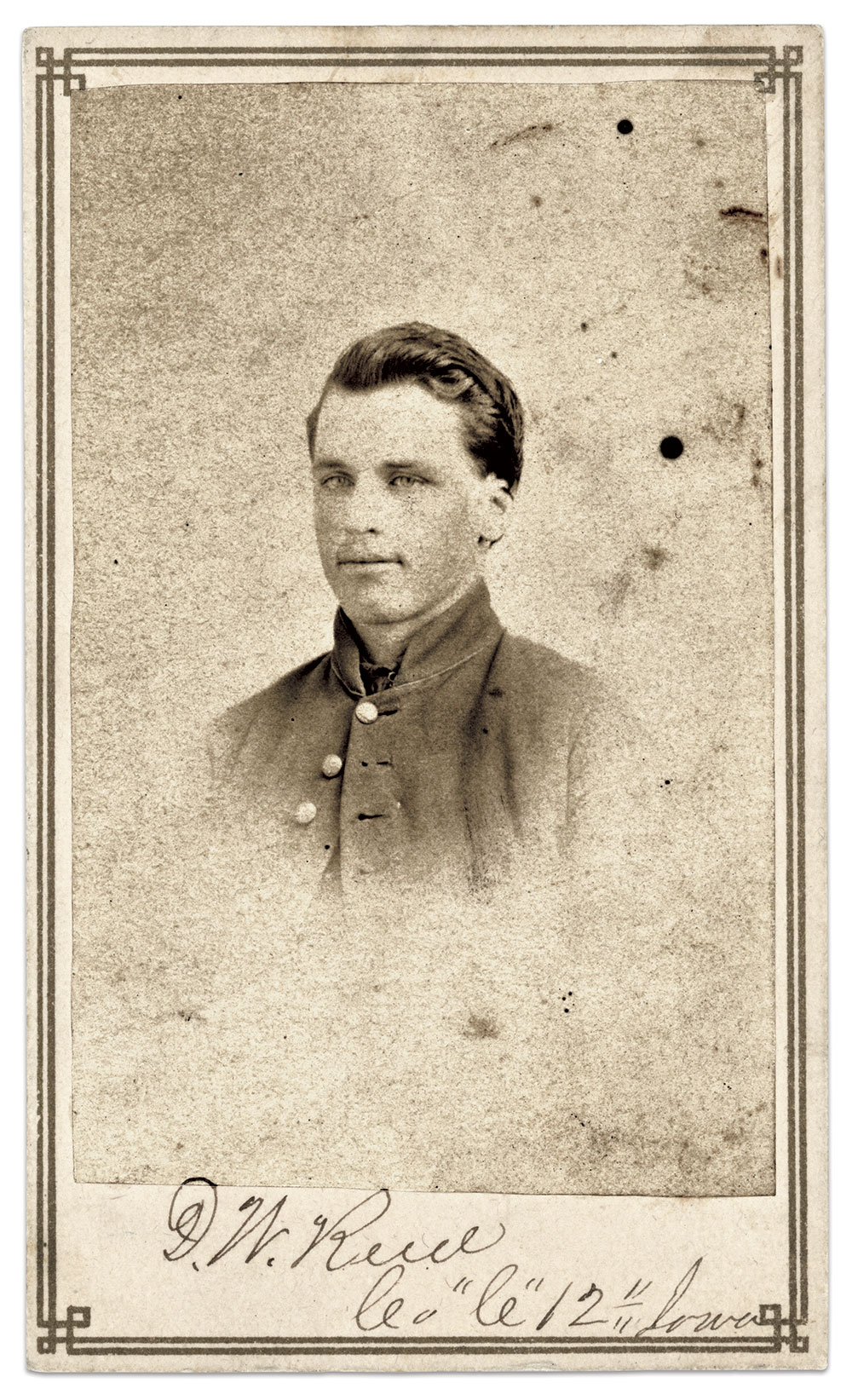

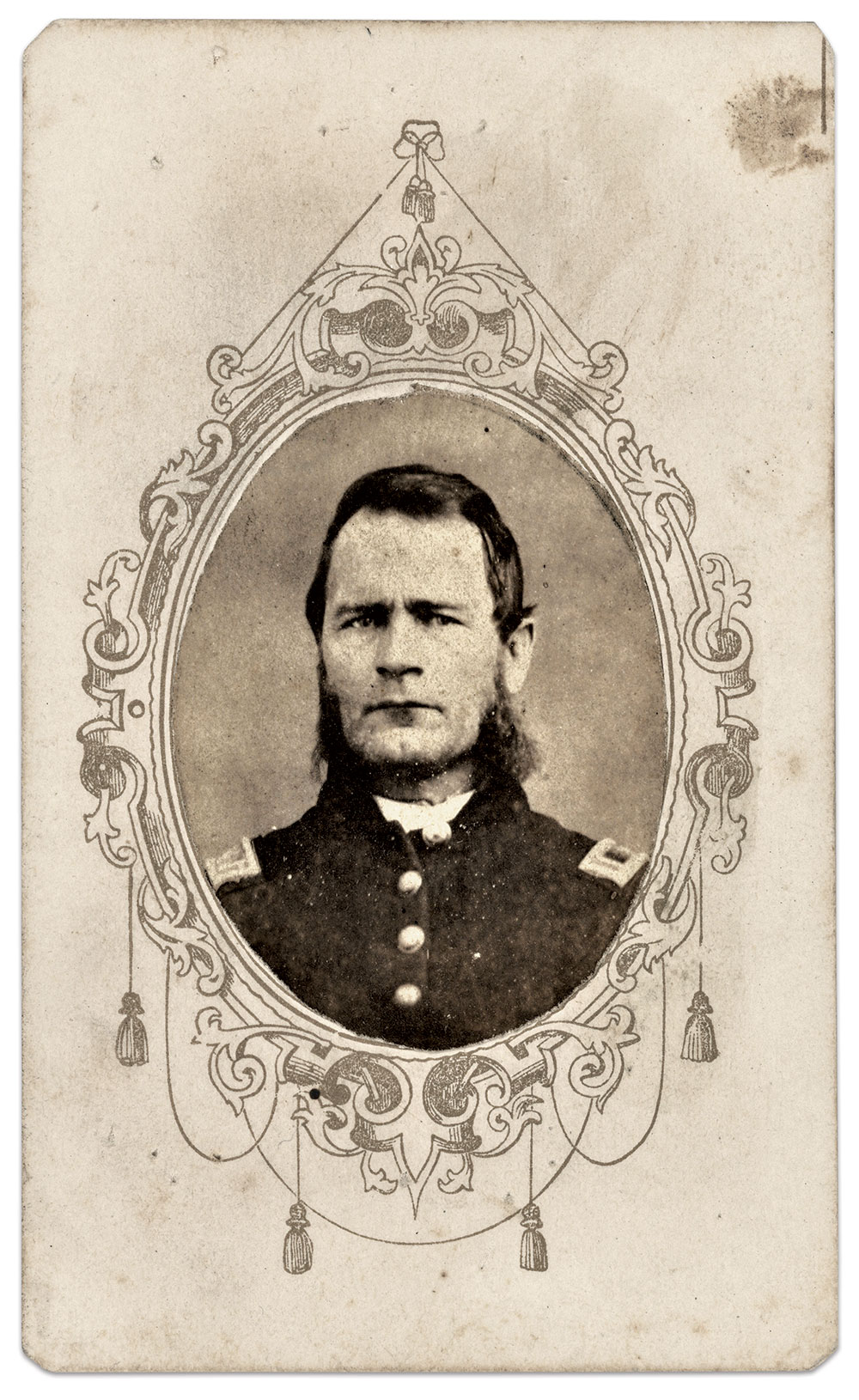

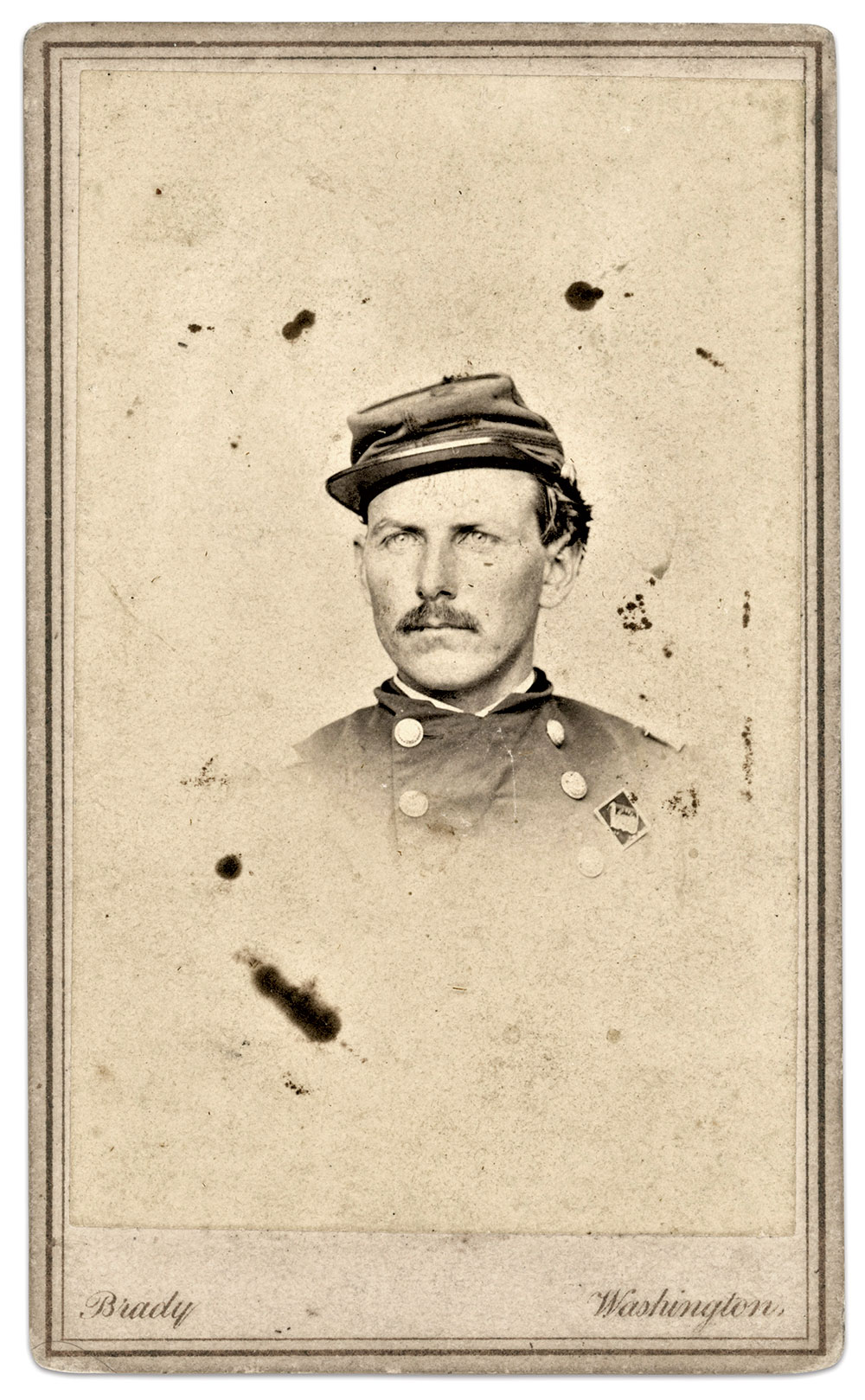

Father of Shiloh National Military Park

Following the establishment of Shiloh National Military Park in 1895, officials appointed a historian to interpret the battlefield for current and future generations of Americans. The man they selected, Maj. David Wilson Reed, was uniquely qualified for the job. Wounded in the thigh during the battle, Reed watched helplessly as he and almost all his comrades in the 12th Iowa Infantry were captured after the defense of the Hornet’s Nest collapsed.

Born in Cortland, N.Y., Reed had relocated with his family to Allamakee County in northeastern Iowa before the war. In the autumn of 1861, he set aside his studies at Upper Iowa University and enlisted with 18 classmates in the 12th. They formed the core of Company C.

Reed and the regiment experienced its first major fight at Fort Donelson. Weeks later came Shiloh, which ended for Reed and so many others in a months’ long stint as prisoners of war. Reed gained his release in August 1862 and returned to the reconstituted 12th. He served through the end of hostilities, ending his enlistment as captain and receiving a major’s brevet.

Active in veterans’ organizations, Reed authored several accounts of his service. Following his appointment as historian of the military park, he played a key role in establishing the battle narrative, especially the interpretation of the Hornet’s Nest. Though historians have questioned some of his methods, it may be fairly stated that Reed is the Father of Shiloh National Military Park. He died in 1916 at age 75.

1863

Company Parade at Corinth

On Feb. 24, 1863, Company A of the 7th Iowa Infantry posed for this portrait in Corinth, Miss. About 50 officers and men were present—half the number that mustered into the company in the summer of 1861. Death from disease and battle took a toll. The 7th fought at Belmont, leaving casualties on the field in its hasty retreat. It took part in the successful assault of Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith’s troops at Fort Donelson. It fought at the Hornet’s Nest on the first morning of Shiloh, holding the line through the afternoon. The Iowans saw action again later at Iuka, and received a mauling at Corinth.

The color bearer of the 7th stands on the right, and the regimental band on the left. On the far left stands a Black man, who may have been a servant to an officer or one of the company cooks. If a servant, this image represents one of the very few showing men of that status who served with Iowa troops.

Champion Hill: Firing into Each Other’s Faces

An Iowa infantry officer recalled the May 1863 Battle of Champion Hill, part of the Vicksburg Campaign, in no uncertain terms: “I have been in what history pronounces greater battles than Champion Hill, but only once did I ever see two lines of blue and gray stand close together and fire into each other’s faces for an hour and a half. I think the courage of the private soldiers, standing in that line of fire that awful hour and a half, gave us Vicksburg, made Grant immortal as a soldier, and helped to save this country.”

One of the Iowans present, 20-year-old Pvt. William Garver, served in the ranks of the 10th Infantry. At some point during the brutal contest, he suffered a severe bullet wound in his hip.

A native of Ohio, he and his family had lived in Indiana and Illinois before settling in Washington, Iowa. In the summer of 1861, he joined the 10th. The regiment participated in operations along the Mississippi at New Madrid and Island No. 10, and the battles of Corinth and Iuka. Garver emerged from these actions uninjured. Following his wounding at Champion Hill, he made a full recovery and remained with the 10th until the expiration of its term of enlistment in September 1864. Garver became active in veterans’ affairs through the Grand Army of the Republic, first in Iowa and later in Kansas, where he died in 1928 at age 85.

On Occupying Vicksburg

Outside Vicksburg on the evening of July 3, 1863, Pvt. Francis Marion Gott of the 20th Iowa Infantry reported for guard duty to “watch the Jonnys” as he noted in his diary. Gott did not record if he saw any, but did mention that he stood along a main road leading to the city the next morning at 9 a.m. when he watched “our own soldiers as they march in to take charge of Vicksburg.” Gott bore witness to the culmination of the long campaign to wrest the city from rebel control and secure the Mississippi River for Union arms.

Gott, an Indianan who relocated to Iowa before the war, had joined Company A of the 20th the previous autumn. He survived his service and died in Oregon in 1924 at age 87.

“Buster” Dykeman Goes to War

Perhaps the best-known officer who had a young son accompany him to war was Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his boy Fred. Lost in time is this child, five-year-old John Henry Dykeman Jr., who went by the nickname “Buster.” His father and namesake commanded Company I of the 39th Iowa Infantry. Buster posed for this portrait in his realistic officer’s costume at some point between January and November 1863, during which time the regiment was stationed in Corinth, Miss. Father and son survived the war. Buster went on to gain admission to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1873, but resigned two years later. He became an engineer and settled in Chicago, where he died in 1914 at age 55.

Hand-to-Hand Fight Near Polk’s Plantation

Confederate efforts to retake Helena, Ark., in the spring and summer of 1863 included a skirmish at Polk’s Plantation, located about six miles from the town. On May 25, a 150-man Union scouting mission intercepted rebel troopers, and the fight that followed escalated to hand-to-hand combat, recounted the lieutenant commanding a detachment of two companies of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry. He also reported two men severely wounded. One of them pictured here, Pvt. James S. Matthews of Company B, suffered a wound in his right leg. Surgeons amputated the limb, but disease set in and he succumbed on May 30. He was 24 and unmarried.

A Pennsylvanian who had relocated to Iowa with his family about 1851, he had joined the regiment in the summer of 1861. His remains rest in Clay Grove Cemetery in Lee County, Iowa, beneath a headstone upon which is inscribed, “fell in defence of his country.”

This carte de visite, showing Mathews in a Merrill cavalry uniform with a revolver tucked into it, is a copy print of an ambrotype or tintype made soon after his enlistment. It was likely made by his family’s request as a memorial portrait.

The Unsolved Case of Capt. Loomis

The rolls of Union officers who suffered unexplained deaths during the war include Capt. James Munson Loomis of the 39th Iowa Infantry. On July 7, 1863, he and most of his Company H guarded a corral a few miles outside Corinth, Miss., when enemy cavalry surrounded and captured them. He is reported as having been killed on September 1 while still a prisoner.

Loomis, a 25-year-old father of two who had settled in Iowa from his native Indiana, had started the war in 1861 as a sergeant in the 4th Iowa Infantry, and received a discharge in November 1862, likely to accept a captain’s commission in the newly-formed 39th.

No details of his fate following his capture eight months later other than the date of his death have yet emerged. At least six men in his company captured with him are reported as “supposed died in rebel prison.” Loomis may have been killed trying to escape from an unnamed Southern prisoner of war camp, or for some act that sparked the ire of his captors.

1864

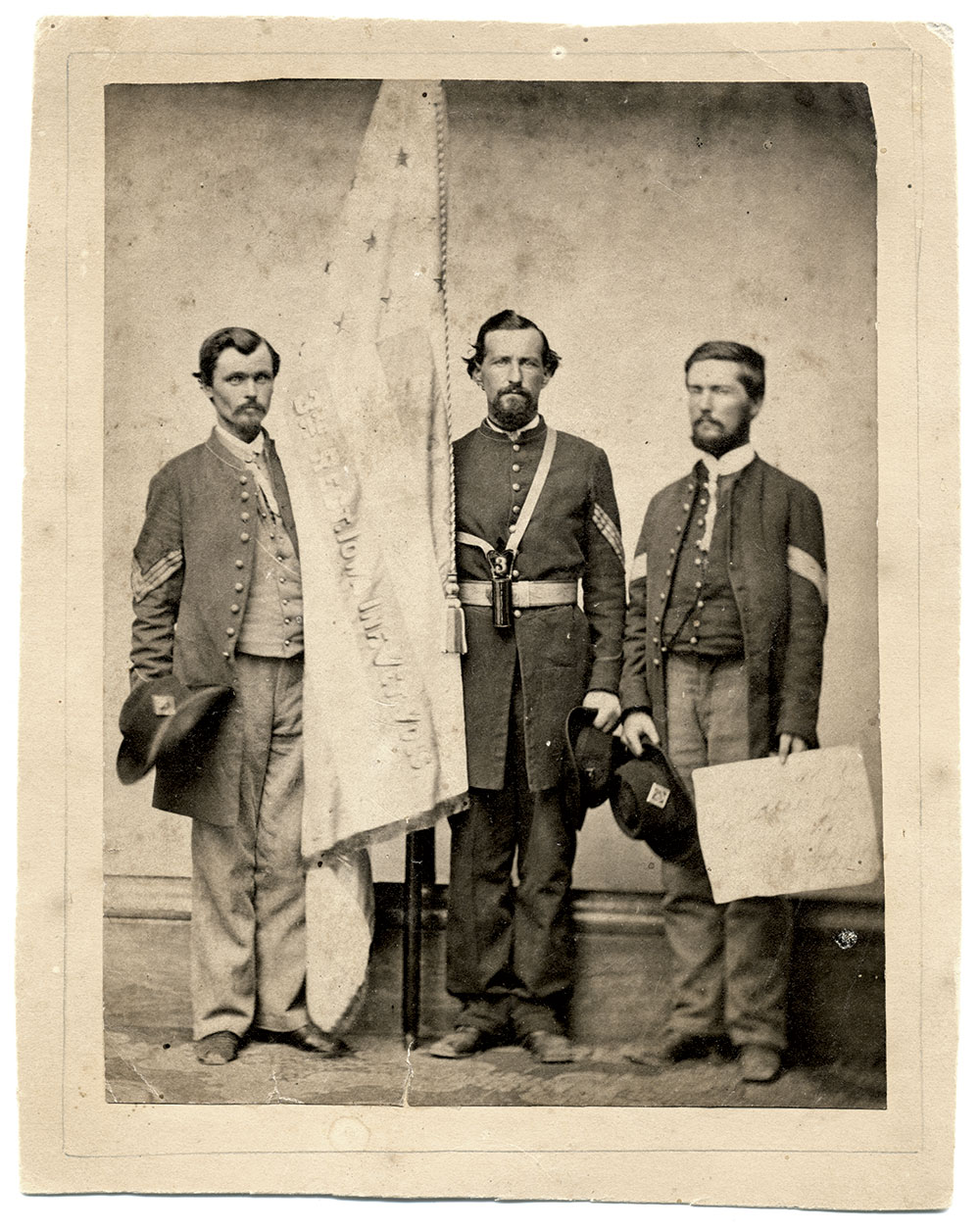

Final Rally ‘Round the Old Flag

A trio of sergeants posed with the colors of the 3rd Iowa Veteran Infantry, a hard-fighting regiment formed in 1861. Its list of engagements spans from Shiloh to Vicksburg to Atlanta. By 1864, its strength had been whittled down to just three companies. In September of that year, the army combined the survivors with its brothers in another depleted regiment, the 2nd Iowa. Each regiment was uniquely honored to retain its regimental identity, and thus officially becoming the “2nd and 3rd Veteran Infantry Consolidated Regiment.”

The combined regiment went on the March to the Sea with the rest of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army, and participated in the Grand Review in Washington, D.C., before mustering out of the army in July 1865.

These sergeants hold caps with 15th Corps badges, which they wore after consolidation. The flag lives on in the collection of the State Historical Museum of Iowa in Des Moines. It is one of three surviving colors from the 3rd. A faded pencil inscription on the placard held by the sergeant standing on the right is unreadable.

— Paul Russinoff

Headquarters at Pocahontas

The 8th Iowa Infantry spent the winter months of 1863-1864 guarding railroads at Pocahontas, Tenn., about 80 miles due east of Memphis. Seen here is the headquarters of the regiment’s colonel, James L. Geddes. The national colors are leaning against an officer’s tent to the center-right of the image, and men stand between the house and the tents.

The 8th left Pocahontas to participate in the Meridian Campaign, a prelude to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea. The location is inscribed in ink on the back of the mount, and the image was in the personal photograph album of Capt. Charles S. Wells (1834-1915) of Company H. Also in Wells’ album is this view of “our band,” which may have been taken in Pocahontas.

Killed at Ezra Church

Charles Henry Loomis showed early promise as a soldier after he joined the 6th Iowa Infantry in July 1861. The New York native and resident of Mount Pleasant, Iowa, soon received a promotion to corporal. Here he wears his uniform and new stripes. Within a year, he rose to sergeant in his Company K. Loomis saw action in nearly every major conflict in which the Army of the Tennessee participated. His luck ran out during the Atlanta Campaign. On July 28, 1864, he was killed at the Battle of Ezra Church, the result of an effort by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to cut the Macon and Western Railroad. Loomis was 25. His remains rest in Georgia’s Marietta National Cemetery.

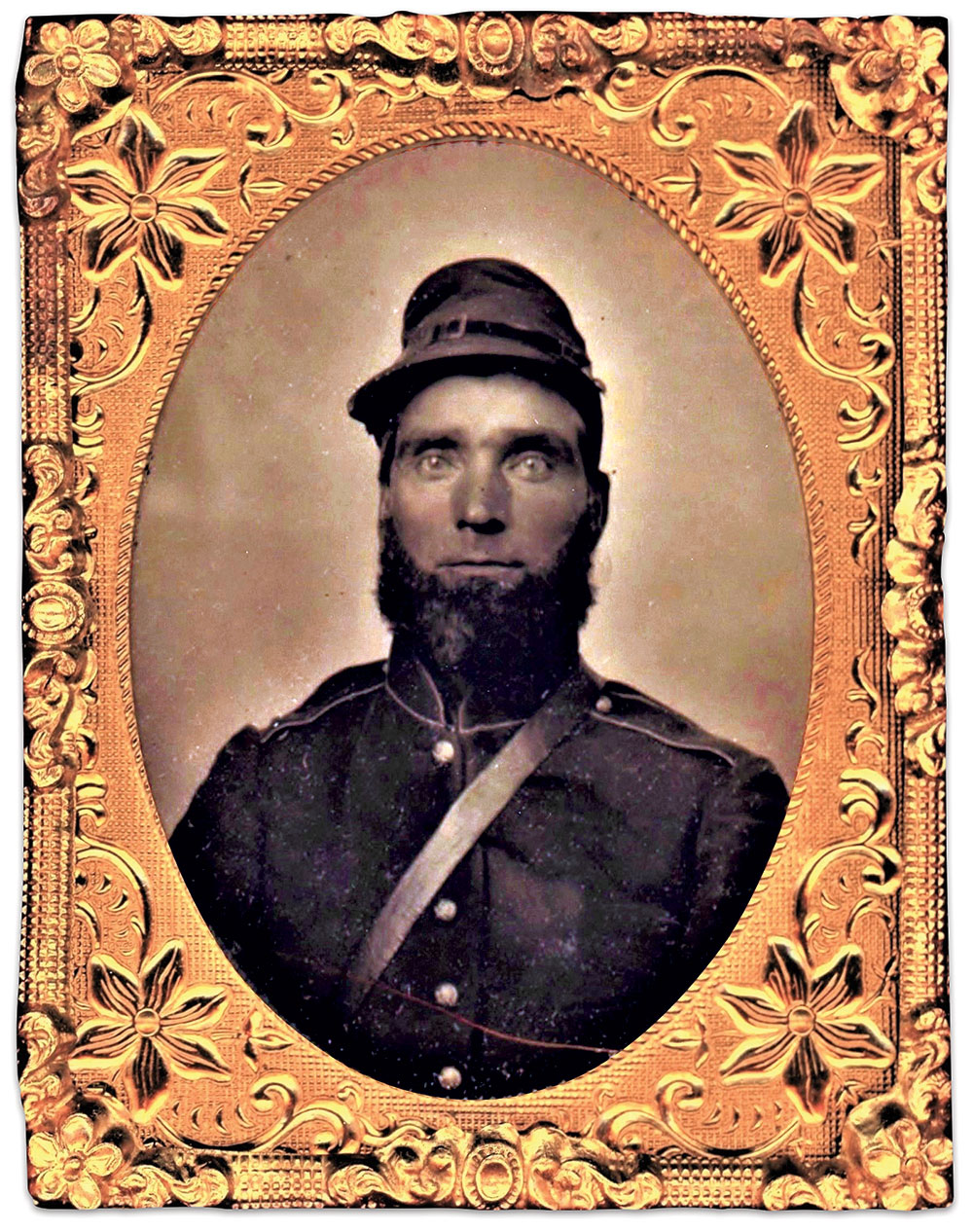

A True Graybeard

As part of a larger Union effort to put more young fighting men on the front lines, state officials in Iowa recruited a regiment of men over the age of 45 to garrison rear areas. Thus came into existence the 37th Iowa Infantry, nicknamed the “Graybeards.” The men guarded railroads and two Illinois prisoner of war camps, in Alton and Rock Island, during their service.

One of them pictured here is a literal graybeard, 58-year-old Andrew Pease. Born in Pennsylvania before the War of 1812, he joined Company I in the autumn of 1862. He died of disease on Jan. 10, 1864, while stationed at Alton and is interred in the national cemetery located on the grounds.

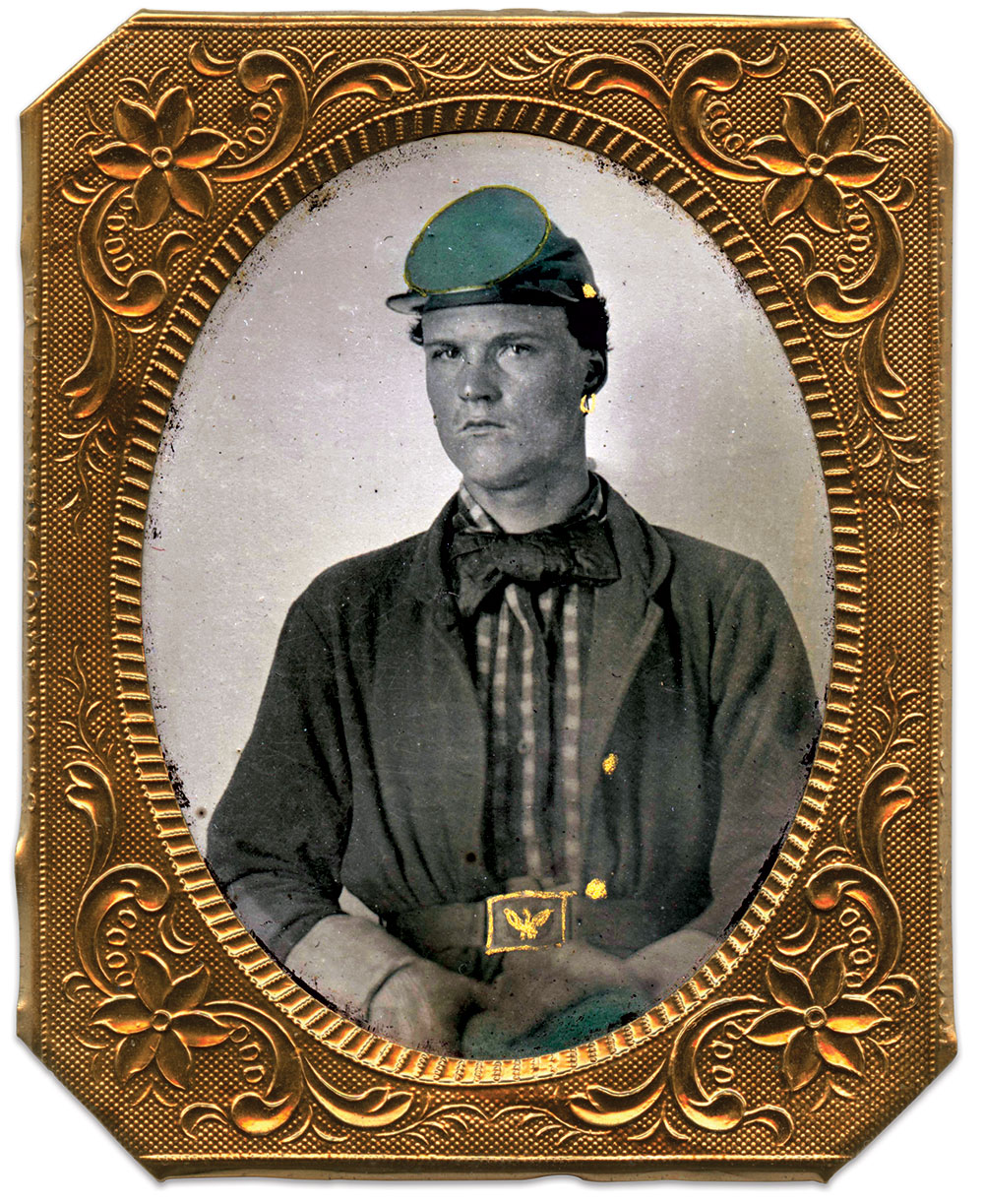

Everyman’s General

Few commanders enjoyed the reputation of Brig. Gen. Charles Leopold Matthies. University-educated and military trained in his native Prussia, he immigrated to America in 1849 and made his home in Burlington, Iowa. Matthies started the Civil War as a captain in the 1st Iowa Infantry for a three-month term, and then joined the state’s 5th Infantry as lieutenant colonel. He advanced to colonel and earned a brigadier’s star for his sterling performance at the Battle of Iuka. A head wound suffered a year later at the Battle of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga ended his service. He barely survived the war, dying in 1868 from liver disease. He was 44. At the time he served as a state senator.

In a series of memorial resolutions fellow senators highlighted a key to Matthies’ success: “As an officer he possessed that happy combination of faculties which enabled him, without relaxing the discipline of those under his command, to sympathize with them, and to make them feel that while he was above them in point of rank in the service, he stood on the same plane as a man and a patriot. Hence he was regarded by his soldiers as a friend whom they could trust, and on whom they could call in time of need with full assurance that they would receive not only his sympathy and counsel, but material aid, if necessary, to the extent of dividing the last dollar in the pocket of their beloved General.”

Bad Day for the 17th Ends in a Trip to Andersonville

Thursday, Oct. 13, 1864, ended in infamy for the 17th Iowa Infantry. The 300-strong regiment guarded the Western and Atlantic Railroad at Tilton, Ga. The rails were the thin supply line that connected Union forces at Atlanta with supply depots at Chattanooga. Protecting the railroad kept critical food and munitions flowing. That afternoon, Confederate Lt. Gen. A.P. Stewart’s Corps attacked Tilton. The 17th Iowa held off the attackers for a few hours after taking cover in a blockhouse, but were ultimately compelled to surrender. Only 31 Iowans evaded capture.

The prisoners included Newton Columbus Michael. A 20-year-old Indiana native who had relocated to Centerville, Iowa, he began his service in Company F in early 1862. He escaped serious harm until falling into enemy hands at Tilton. Michael survived six months in Andersonville, and ended his enlistment as a corporal. Chronic health issues blamed on his time in Andersonville plagued him for the rest of his days.

Back in Centerville after the war, he married and became a partner in a confectionary and canned fruit business, as well as a general merchandise establishment. He eventually moved to Los Angeles, where he died in 1920 at age 76.

A Teenager in Andersonville

While the healthy members of the 16th Iowa Infantry captured at the Battle of Atlanta and held in Andersonville were soon exchanged, the wounded and sick remained. The Iowans left behind included Peter Kiene Jr. of Company E. The Iowa-born son of a prominent Swiss immigrant in Dubuque, Kiene joined the 16th at age 15 in early 1862. Before the end of the year, he suffered a wound at Corinth, Miss., and fell into enemy hands for seven months. He’s pictured here after his return from captivity and reenlistment as a veteran volunteer.

Months later at Atlanta, Kiene, now 17, suffered his second wounding and capture. According to a family story, he had help at Andersonville thanks to an arrangement with a Southern woman who visited the camp. She had a brother in the Confederate army imprisoned at Rock Island, Ill., not far from Dubuque. They made a deal: She would care for Kiene in return for his father, Peter, Sr., doing the same for her brother. Both survived. Kiene’s ordeal at Andersonville ended after seven months, eerily similar to his Corinth experience.

Kiene returned to his family in Dubuque and joined with his father in the iron business. Kiene went on to become successful in real estate and insurance, and active as a philanthropist and in the Grand Army of the Republic. He suffered a paralytic stroke in 1912 and succumbed to its effects at age 66. His wife, Caroline, and two children survived him.

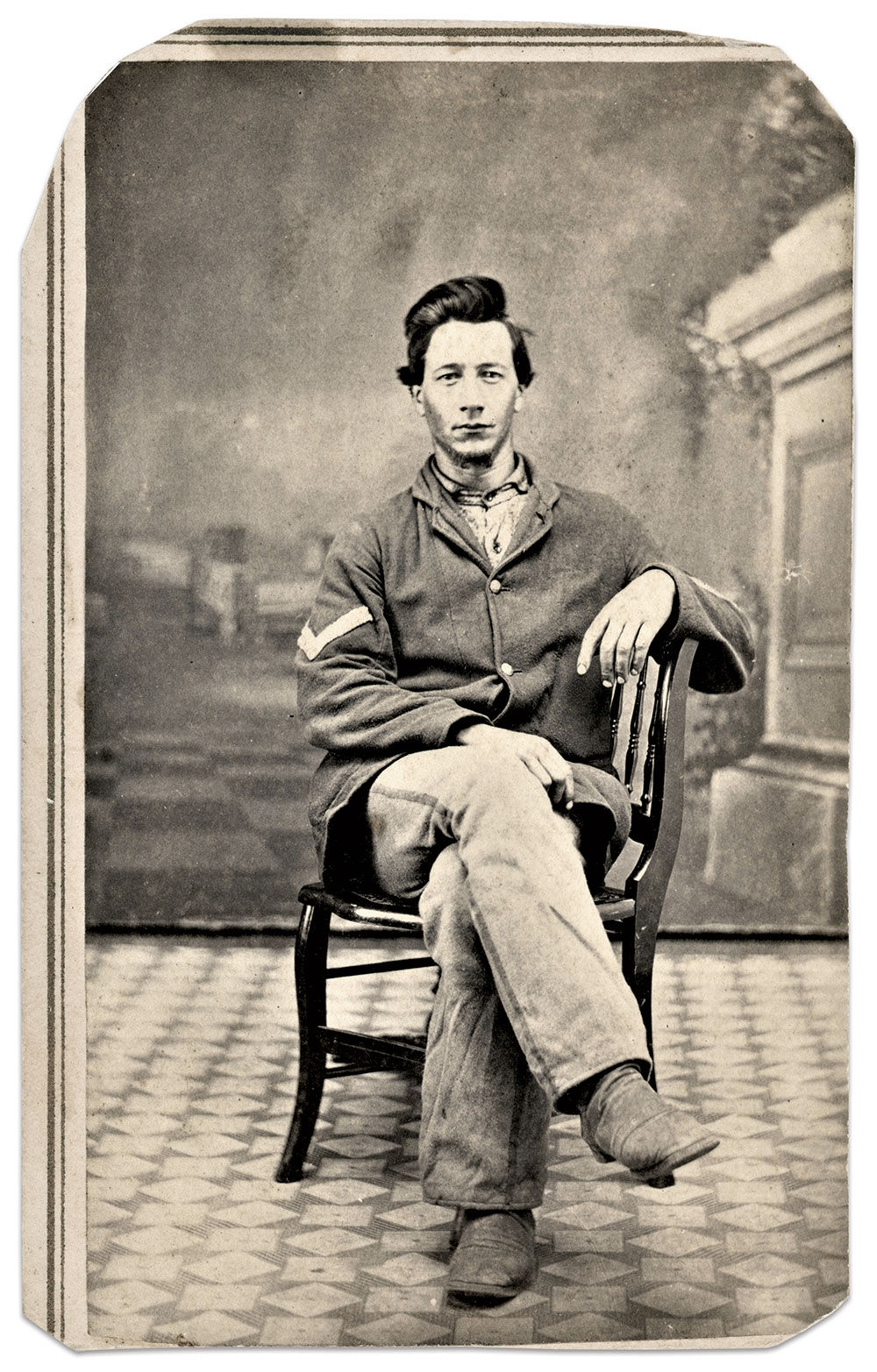

The Face of Victory on a Veteran Volunteer

Josiah Benjamin Romig personifies the image of the veteran volunteer in the West. His look is confident, yet without hint of arrogance about him. He has no need for adornment or special pins. His fatigue blouse is enough. Corporal Romig bears himself with the assurance of a soldier who saw action from Shiloh to Vicksburg to Atlanta to Savannah; all the major campaigns of the West. This is the face of victory.

Ohio-born Romig joined Company I of the 13th Iowa Infantry in October 1861, and re-enlisted as veteran volunteer three years later. When the war ended, he returned home to Washington, Iowa, for a short time. But wanderlust caught up with him. Perhaps it was the constant travel of the army or a need to keep moving, but Romig did not stay in one place very long. By the late 1880s, he lived in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, and ultimately resided in Pasadena, Calif. He died there in 1918 at age 83. His wife, Amanda, and four children survived him.

A Death at Opequon

Iowa’s Civil War story is centered in the West. There are exceptions, including a brigade composed of the 22nd, 24th and 28th infantries. It served in the Shenandoah Valley, sent from New Orleans in 1864 to reinforce Maj. Gen. Phillip H. Sheridan’s forces. The Iowans belonged to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, 19th Army Corps.

One of its number is pictured here: David J. Davis of the 22nd. He began his service in 1862 as a private in Company A and advanced to captain by early 1864. Along the way, the 22nd participated in the Vicksburg Campaign, where Davis suffered a wound at Port Gibson, La., in May 1863.

In July 1864, the 22nd received orders to report from New Orleans to the Shenandoah Valley. Two months later at the Third Battle of Winchester, or Opequon, the regiment took heavy casualties. Davis and another captain died, both instantly killed at the head of their companies. “Their conduct was heroic, and they died at the post of honor,” noted a regimental historian. Davis was in his late twenties. His remains rest in Winchester National Cemetery.

In Dakota Territory

As the war entered its final year, merchant Joel Gilbert Frink joined the cavalry. A Vermont-born merchant who had settled in the Mississippi River town of MacGregor a few years before hostilities began, he was, at age 33, one of the older volunteers when he mustered into the ranks of the state’s 6th Cavalry in September 1864. The regiment had been organized in 1862 to protect its borders against Native Americans, and its companies scattered across the frontier. Frink spent his enlistment with Company L at Fort Randall in Dakota Territory. He mustered out about a year later and eventually settled in North Dakota, where he died in 1901 at about age 70. His wife, Helen, and three children survived him.

Death at His Doorstep

Captain Philip Henry Bence of the 30th Iowa Infantry encountered the enemy in the most unlikely of places—his own doorstep. On Oct. 12, 1864, a dozen men in federal cavalry uniforms rode into Davis County in southern Iowa. They were Missouri bushwhackers led by James Jackson, a man with a reputation for violence, especially towards African Americans.

At first, Jackson and his raiders robbed citizens and took prisoners. As the day progressed, they turned to murder. Three men were killed. Thomas Hardy refused to turn over his wagon and team, and fell with multiple gunshot wounds. Eleazar Small, a veteran of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry, approached the raiders assuming them acquaintances home on leave.

The final victim was Bence. Home on furlough to recover from a wounded hand he had suffered at the Battle of Atlanta, Bence met the raiders at his front door. When their intentions became obvious, Bence asked to not be shot in sight of his wife, Charlotte, and four children. Jackson and his men mounted Bence and another prisoner on a horse and led them into Missouri. At some point, Jackson turned in his saddle, placed a pistol to Bence’s head and pulled the trigger. He shot Bence at least once more before leaving his body by the side of a road.

Less than a year later, in June 1865, Jackson peacefully surrendered and took the loyalty oath to the U.S. government. Fate caught up to him in Pike County, Mo., where militiamen captured and executed him.

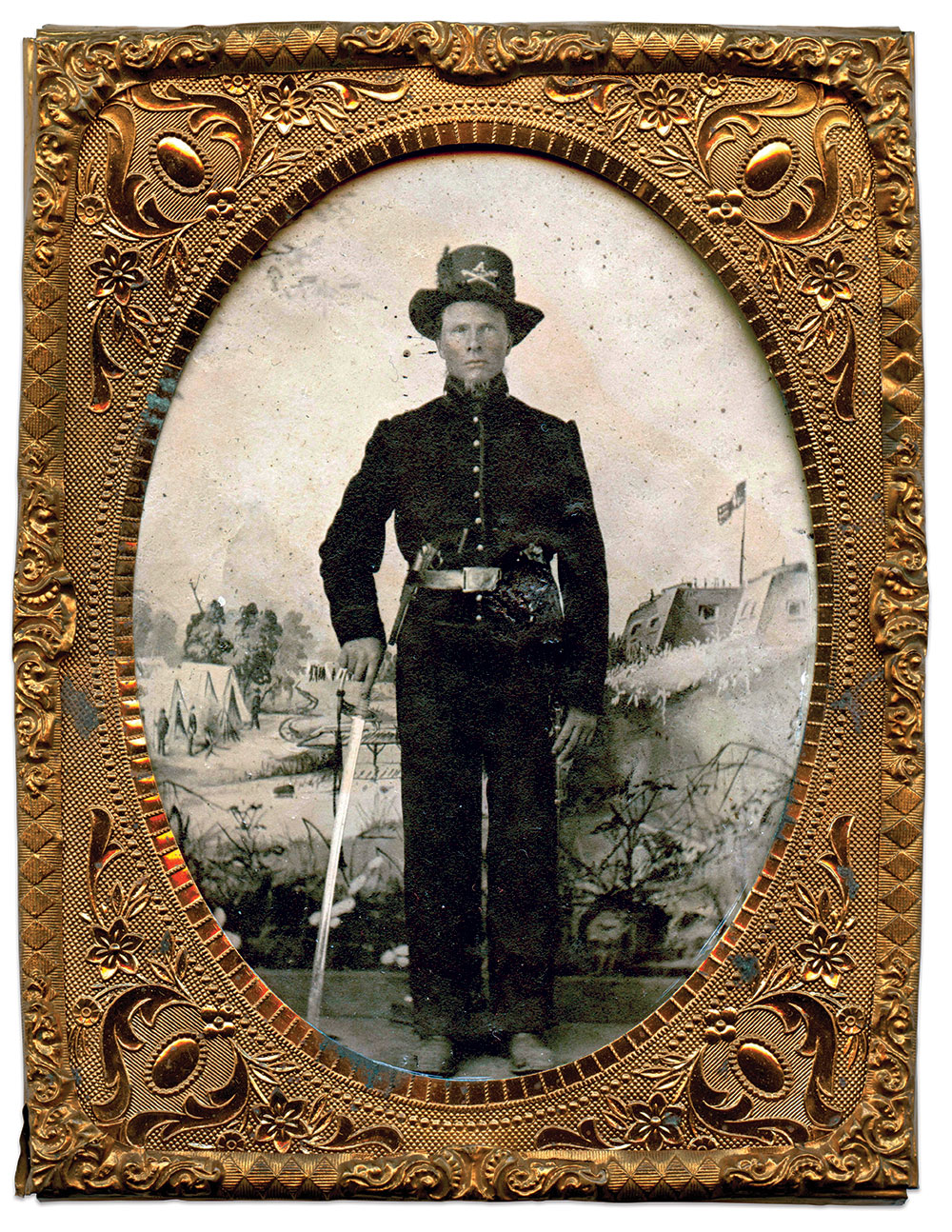

Deadly Skirmish at Terre Noire Creek

Seated in full uniform with his fully flocked Hardee hat, Theodore Y. Creamer appears ready to take on the rebel army. Every button is set and polished, and he has a Colt Model 1851 navy revolver tucked into his belt. The native Pennsylvanian and his fellow troopers in the 1st Iowa Cavalry saw plenty of action in the Western Theater during the Civil War. Creamer advanced to corporal and suffered two wounds as the result of skirmishes in Arkansas. The first occurred at Chalk Bluff on May 2, 1863. The second, at Terre Noire Creek on April 2, 1864, proved mortal. He died in nearby Camden, and his remains were eventually moved to Louisiana and interred in Baton Rouge National Cemetery.

Atlanta to Andersonville

The Battle of Atlanta on July 22, 1864, took a heavy toll on Iowa troops in Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army. One of the Hawkeye regiments, the 16th, found itself on the extreme left flank of the Army of the Tennessee—the end of the Union line. At one point that afternoon, a Confederate division led by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne attacked. The 16th and other forces engaged in a desperate fight to prevent Cleburne from rolling up the federal flank. The Iowans held until their ammunition ran out. The order to withdraw came too late. Surrounded by Confederates, 225 men from the 16th surrendered.

The Confederates transported enlisted men to Andersonville Prison. The group included Alexander M. Apple, a corporal in Company I. A 22-year-old Jewish immigrant born to ethnic Hungarians in Freistadt, Austria, he had immigrated to America in 1854. Apple (or Appel) joined the 16th in January 1862. According to a postwar sketch of soldiers of the Jewish faith in the Civil War, Apple distinguished himself at Shiloh when he saved the colors from falling into enemy hands.

At Andersonville, Apple and many of his healthier comrades were exchanged about a month after the battle, avoiding the long-term effects of malnutrition and disease. He returned to the 16th and, in January 1865, received a promotion to commissary sergeant.

After the war, Apple settled in Philadelphia and became a shirt manufacturer. Active in the Grand Army of the Republic as a post commander and the Soldiers’ Home at Erie, Pa., he died in 1915 at age 73. Three children survived him.

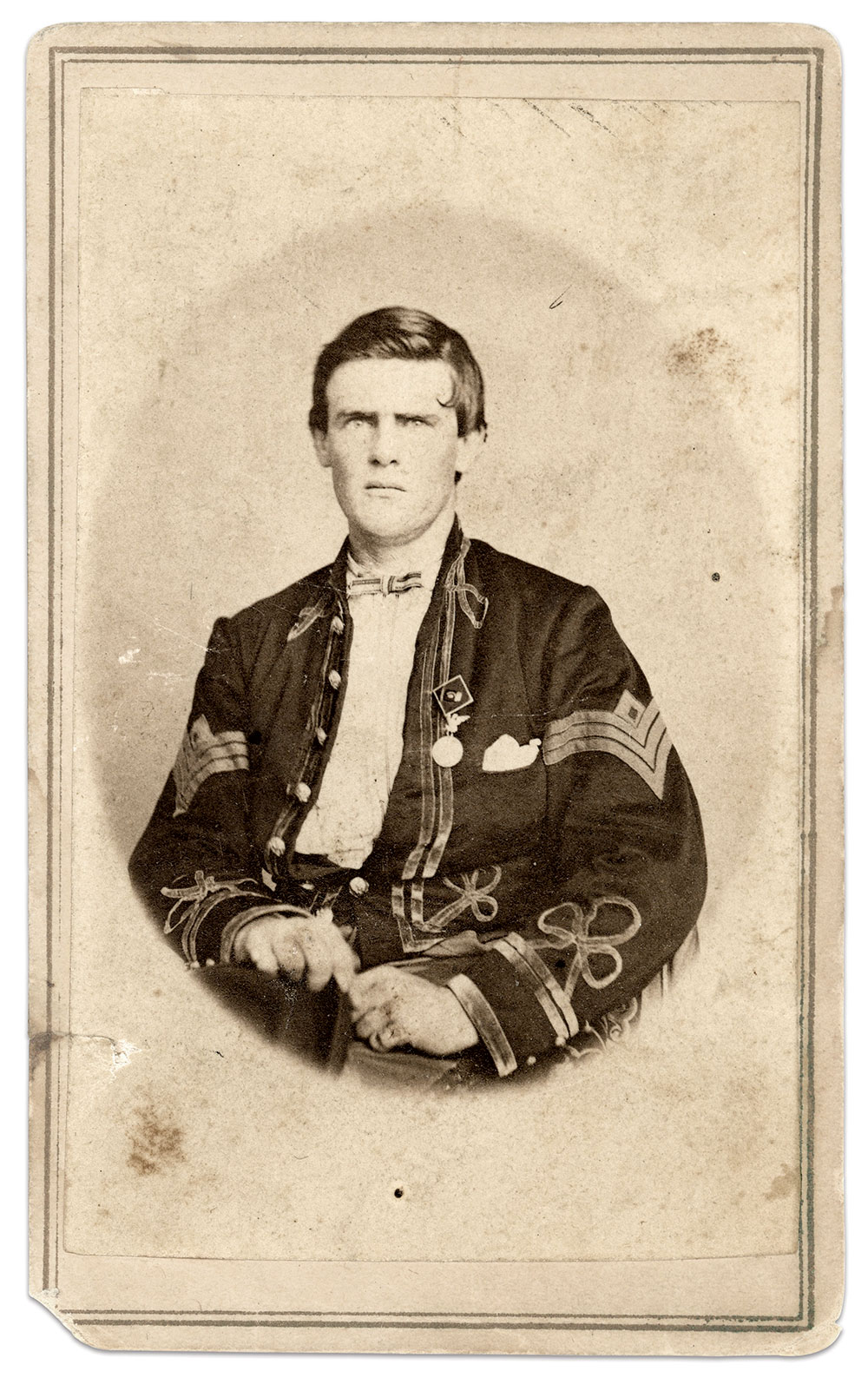

Not a Zouave

At first glance, one might assume that the natty uniform worn by 1st Sgt. Thomas Jackson Brant of the 4th Iowa Infantry indicates the regiment adopted a Zouave style upon its organization in 1861. However, no evidence has yet surfaced that the 4th made such a move, according to Daniel J. Miller, author of American Zouaves, 1859-1959. Miller notes that photographic evidence suggests the 4th adopted Zouave-influenced dress late in the war. Brant’s portrait supports this observation, as he earned his first sergeant’s stripes and lozenge in October 1864. Brant, an Ohio-born resident of Lyon Eagle, Iowa, at his enlistment, proved his fighting mettle in the campaigns of Vicksburg, Atlanta, and elsewhere during his enlistment. In this portrait, he sports a 15th Corps badge and Army of Georgia pin. Brant settled in Indiana after the war and died in 1911 at age 61. A daughter survived him.

1865

Western Wit vs. Soft Bread Soldiering

Much has been made of the contrasting appearance of the Eastern and Western armies that marched in the Grand Review at Washington, D.C., in May 1865. One of the Iowans present, Sgt. William Stroup Fultz of the 11th Iowa Infantry, wrote of his encounter with the East Coasters a couple weeks before the event: “They all wore white gloves and paper collars and long scarfs fluttered from their necks. This peacock style as our boys termed it was held in great contempt by Shermans plainly dres’t roystering army. And many were their sharp comments on that kind of soft bread soldiering as they termed it. For a time, those white gloved gentry would reply to the comments but they soon found out that they were no match in wit for the western boys.”

Fultz, a Pennsylvanian of German descent, had moved to Muscatine, Iowa, at age 14 with his family, and worked in his father’s sawmill until the war began. He joined Company D of the 11th in 1861. His wartime letters and journal entries formed the basis of his reminiscences, History of Company D. It includes the anecdote here and other glimpses of life in camp and on campaign.

Fultz mustered out in July 1865. He is pictured here about this time wearing what appears a private purchase jacket or a modified mounted service jacket, adorned with an Army of Georgia medal, as well as three 17th Corps arrows—an unusual arrangement. He returned to Iowa, where he prospered as a fruit grower and family man. Fultz died in 1915 at age 79. His wife, Martha, and five children survived him.

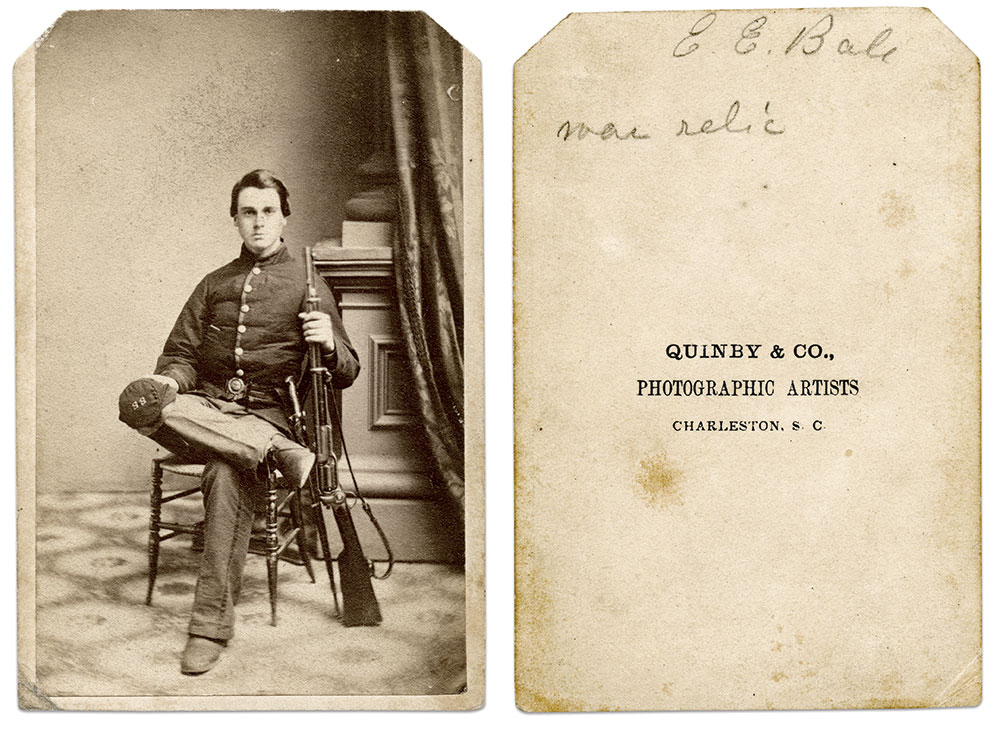

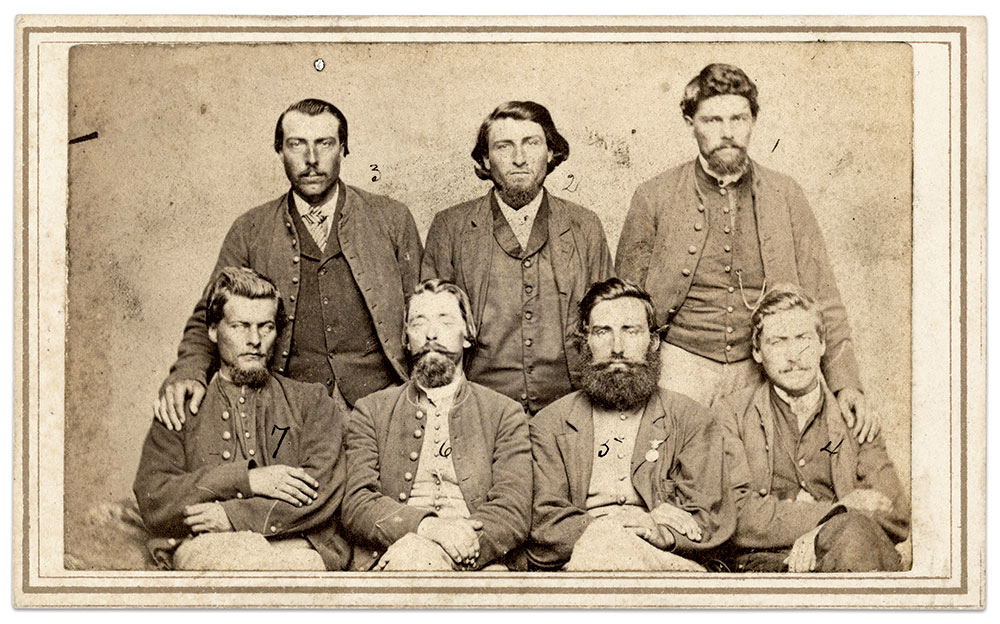

“War Relic”

Soldiers on both sides of the war collected souvenirs on camp and campaign. Union officer Edward Edwin Bale picked up one that he tucked into his photograph album—a carte de visite of a South Carolina sharpshooter. Bale likely discovered the image in the Palmetto State in early 1865 as he and his comrades in the 16th Iowa Infantry marched in the Carolinas Campaign.

Born in London, England, Bale immigrated to America and settled in Dubuque, Iowa. He began his military service in 1861 in the ranks of the state’s 1st Infantry, a three-month regiment that fought in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. He returned to the army in March 1862 with the 16th, which participated in every major action with the Army of the Tennessee. Along the way, Bale rose in rank from sergeant to first lieutenant.

The 16th spent January and February 1865 in South Carolina, including the Charleston area. The image of the Confederate is marked with the name and address of Charleston photographer Charles J. Quinby. Though the identity of the soldier is currently lost in time, his two-piece Palmetto tree belt buckle, Colt Revolving Rifle and the letters SS on his cap likely associate him with the Palmetto Sharpshooter Regiment or the 1st Battalion, South Carolina Sharpshooters.

Bale mustered out of the service with the survivors of the 16th in July 1865. He eventually settled in Streator, Ill., where he operated a supply store until his death in 1888. His wife, Levancia, and two young children survived him. He was about 45.

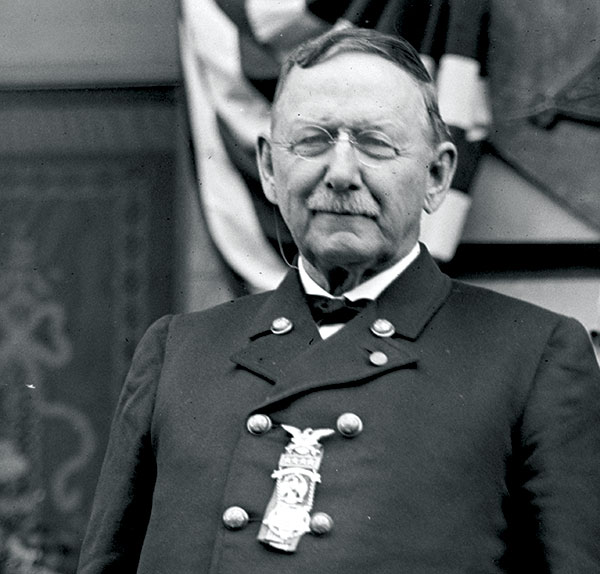

In Sherman’s Place at the Grand Review

Few citizen soldiers in the Union army can claim the record of David James Palmer. Born in Pennsylvania, he immigrated to Washington, Iowa, with his family early in life. When war came in 1861, Palmer enlisted as a private in the 8th Iowa Infantry. Shot in the chest and left shoulder at Shiloh, he fell into enemy hands. Neglected by his captors for two days, he managed to crawl back to Union lines. Sent home to recuperate, he raised what became Company A of the 25th Iowa Infantry, and became its captain. Nine months later, during the Vicksburg Campaign, he advanced to lieutenant colonel and commanded the regiment through the war’s end.

Along the way, Palmer befriended and earned the respect of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. At the Grand Review in Washington in May 1865, Sherman passed command of his army to Palmer when it came time to join dignitaries on the viewing stand. Palmer led the Army of Georgia through the rest of the review. Palmer’s wartime portrait pictures the 25-year-old officer, as he must have appeared that day, proudly wearing a 15th Corps badge.

Palmer mustered out of the service in July 1865 and returned to Iowa. He went on to serve four terms in the Iowa Senate, representing Washington County. Active in the Grand Army of the Republic, Palmer commanded the Department of Iowa in 1907 and served as the National Commander-in-Chief of the G.A.R. in 1914. The culmination of his tenure was to review the old veterans as they marched again down Pennsylvania Avenue 50 years after the Grand Review.

Palmer passed away at the age of 89 in 1928.

Brothers in Arms, Ready to Go Home

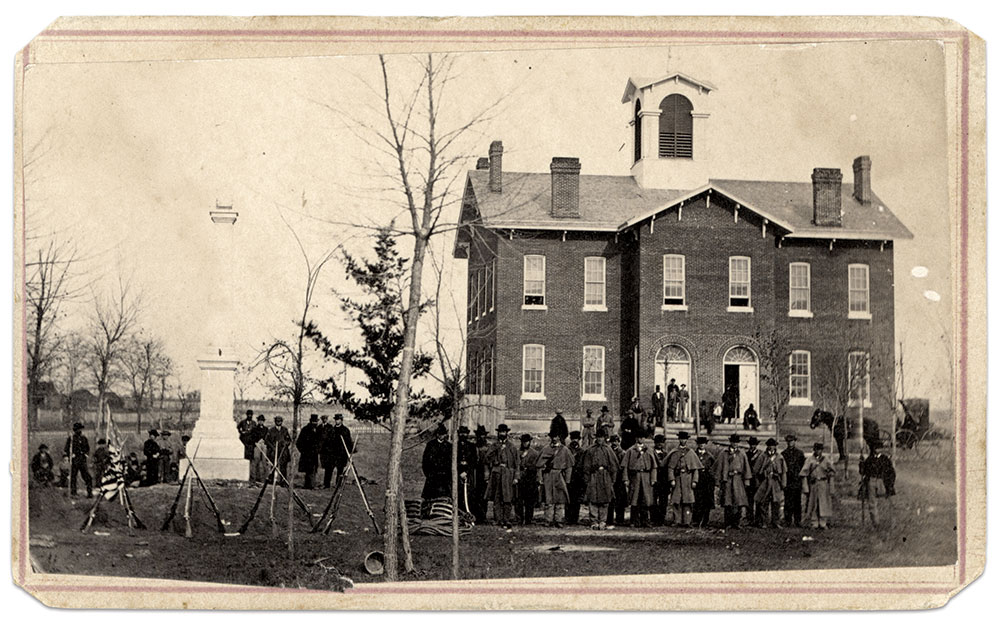

Remembering the Fallen at an 1865 Monument Dedication

One autumn day in 1865 at Hopkinton, Iowa, a crowd of soldiers and townspeople gathered to dedicate a monument to local men who had fallen during the war. Among the dead were students who had attended the local Lenox Collegiate Institute.

The young scholars had been encouraged by the president of the institute, Rev. J.W. McKean, A.M. An anecdote in the History of Delaware County, Iowa, and Its People recounts the event:

“One morning a recruiting officer attended chapel service and after a strong and noble appeal by President McKean for the young men to obey the call of President Lincoln to enlist in the army of the Union, he informed the students that a recruiting officer was present and all who wished to enlist should arise. All arose and enlisted but one and he was too young. The faculty and girl students were in tears and President McKean closed the tender scene by saying, ‘Well, boys, if all of you are going, I am going too.’ President McKean resigned May 6, 1864, and entered the army as captain of a company in which all but two of the students enlisted. The work of the institute was suspended till the fall term. July 9, 1864, Captain McKean died in the army at Memphis, Tenn. A fine monument on the college campus commemorates his name and the names of others who gave their lives for the preservation of the Union. This monument at a cost of over fifteen hundred dollars was dedicated November 17, 1865, which makes it the oldest monument in Iowa and probably in the entire United States erected by public subscription in honor of the soldiers of the Civil War.”

Though Lenox College closed in 1944 during World War II and plans to reopen it never materialized, the monument still stands tall in Hopkinton.

Michael Huston leads the Iowa Civil War Images group on Facebook. He is a farmer and territory manager for Pioneer Seeds by day, and by night an amateur historian and genealogist who collects images of Iowa soldiers with an emphasis on his home county of Washington, Iowa. He is proud to be the descendant of five federal soldiers: three Iowans, one Kansan and one Pennsylvanian.

Robert Welch has had a lifelong interest in Iowa’s role in the Civil War. Growing up in eastern Iowa, he was drawn to study the era after visiting a local reenactment as a child. Welch holds a PhD in American history from Iowa State University. He lives in Vermillion, South Dakota, and works for the University of South Dakota.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.